The Music Professor Online Judith Bowman

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-music-professor-online-judithbowman-2/

ebookmass.com

Four Leaf Felony (Holiday Cozy Mystery Book 1) Tonya Kappes

https://ebookmass.com/product/four-leaf-felony-holiday-cozy-mysterybook-1-tonya-kappes/

ebookmass.com

Thermodynamic Analysis and Optimization of Geothermal Power Plants Can Ozgur Colpan

https://ebookmass.com/product/thermodynamic-analysis-and-optimizationof-geothermal-power-plants-can-ozgur-colpan/

ebookmass.com

CEH Certified Ethical Hacker All-in-One Exam Guide, 5th Edition Matt Walker

https://ebookmass.com/product/ceh-certified-ethical-hacker-all-in-oneexam-guide-5th-edition-matt-walker/

ebookmass.com

Management

Information Systems 13th Edition Kenneth Laudon

https://ebookmass.com/product/management-information-systems-13thedition-kenneth-laudon/

ebookmass.com

Matematicas II: Calculo Integral Tenth Edition, Ap Edition. Edition Bruce Edwards

https://ebookmass.com/product/matematicas-ii-calculo-integral-tenthedition-ap-edition-edition-bruce-edwards/

ebookmass.com

PREFACE

The focus of this book is the formulation, product development, testing, and stability of semisolid and liquid dosage forms. Formulations of this type are important throughout the industry, and are an essential vehicle for delivering pharmaceuticals safely and effectively to their intended target. Understanding the chemistry of surfactants and surface phenomena is key to successfully formulating complex multicomponent formulations.

The formulation of semisolid dosages requires mixing several ingredients to produce a uniform, homogeneous, stable product that can be filled into suitable containers for the end user. This is also applicable to some liquid formulations that are multicomponent systems. The mixing of various ingredients that may be mutually immiscible liquids containing partially soluble or insoluble materials to form a uniform, stable system requires a thorough knowledge of chemistry. The required knowledge of physical, organic, and analytical chemistry that is essential for pharmaceutical formulation development is well documented in various books and research publications. The purpose of this book is not to give fundamental details of the chemistry, but to draw attention to the chemical principles underlying the formulation development of complex mixtures. As some of the medications will be delivered through specialized devices, a basic knowledge of engineering and, to a certain extent, physics is also beneficial. Furthermore, an important aspect for any chemist or pharmacist involved in pharmaceutical drug product development is an awareness of the regulatory agency’s requirements, generally known as the “Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls” part of a drug product regulatory filing. In this book we have focused on surfactants, thickeners, surface chemistry, drug delivery systems, methods used for characterization, and regulatory aspects of testing drug products.

We hope that this book will be helpful to scientists involved in the drug product development of semisolid and liquid dosage forms, and that it will give newcomers to this field a broad perspective of the chemistry involved in formulating and testing drug products.

The process of writing and reviewing chapters was very time-consuming and took many hours of personal time away from our families. We are

thankful to our colleagues and friends who assisted us at various stages. We remain indebted to our wives Anuradha and Karen, and our family members who supported us throughout the long process.

Vitthal S. Kulkarni and Charles Shaw

September 2015

CHAPTER 1 Introduction

Every year, several new drug products based on either new drug substances or generics of existing drug products are approved and enter the market. In 2014, approximately 95 Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs, i.e., generic) and 106 New Drug Applications (NDAs) were approved by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), a division of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This demonstrates that Research and Development within the pharmaceutical industry is a very competitive field. Achieving success in drug formulation development requires a combined knowledge of chemistry, chemical and process engineering, and the regulations. Drug product development activities include aspects of preformulation/formulation development (including compatibility of the API with formulation excipients, and the compatibility of the ingredients and finished formulation with the manufacturing process, process parts, and container-closure system), as well as aspects of manufacturing and stability testing.

Due to concerns relating to toxicity and possible side effects, very few drug substances can be directly administered to the body. Additionally, the amount of the drug substance administered (i.e., the maximum daily dose) is often in milligram or microgram quantities. As a result, it is necessary to mix the drug with other nondrug (inactive) ingredients in such a way that the drugs can be safely delivered to their target within the body.

The US FDA definitions for active ingredient, drug, and drug products are:

• Active Ingredient: any component that provides pharmacological activity or other direct effect in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease or affects the structure or any function of the body of man or animal.

• Drug:

• A substance recognized by an official pharmacopeia or formulary.

• A substance intended for use in diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease.

Essential Chemistry for Formulators of Semisolid and Liquid Dosages © 2016 Elsevier Inc. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801024-2.00001-7

• A substance (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body.

• A substance intended for use as a component of medicine but not a device or a component, part, or accessory of a device.

Biological products are included within this definition and are generally covered by the same laws and regulations, but differences exist regarding their manufacturing process.

• Drug Product: a finished dosage form that contains an active drug ingredient, generally, but not necessarily, in association with other active or inactive ingredients.

As an example, a tablet of Ibuprofen of 200 mg strength may actually weigh 500 mg, indicating that to deliver 200 mg of the drug substance, 300 mg of inactive ingredients are added to help safely deliver the drug to its destination. The added inactive ingredients might also help to keep the drug stable for a finite period. Therefore, converting a drug substance into a safe and effective drug product is equally as important as inventing the drug itself. This process of making drug products by combining the drug substance (the API) and the necessary inactive ingredients (the excipients) is called the formulation process. When formulating a drug product, the goal is to make a safe and effective product that has an acceptable shelf life, which can be easily administered (to promote patient compliance).

Pharmaceutical formulations are mixtures of the pharmaceutically active ingredient and selected inactive ingredients. Solution formulations that are used for injectable dosage forms generally have fewer inactive ingredients— such as water, cosolvents, buffering agents, and pH-adjusting agents. As a result, they are much simpler to formulate compared to some of the semisolid formulations used for topical administration. The inactive ingredients used in semisolid formulations may include water, oil, surfactants, emulsifiers, stabilizers, chelators, preservatives, and pH-adjusting agents. These types of formulations tend to be complex due to interactions between the various ingredients and consequently require considerable development efforts during the formulation process. Furthermore, when formulating a generic version of an existing marketed product, reverse engineering of the reference drug product is often challenging for semisolids.

For all types of formulations, product development efforts require putting together all of the ingredients, testing their mutual compatibility (e.g., the drug substance with the inactive ingredients, and between one inactive ingredient and another), the solubility of the API in the formulation

Surfactants, Lipids, and Surface Chemistry

2.1 INTRODUCTION

This chapter presents an introduction to surface chemistry and surfactants in pharmaceutical formulations. The choice and quantity of surfactants are essential factors in the formation of stable and efficacious emulsions as pharmaceutical dosage forms (including oral, topical, and injectable/infusible dosage forms). Understanding the physical chemistry of surfactant molecules in aqueous systems and at the air–water or liquid–liquid interface is fundamental to designing drug delivery systems. Important parameters include surface tension, contact angle, and critical micelle concentration. Surfactants are “amphiphilic” molecules (or “amphiphiles”), containing both hydrophilic and hydrophobic portions on the same molecule. They have been termed “surface active agents” due to their activity at the air–water or water–oil interfaces, reducing surface tension and improving miscibility. They are also

Table 2.1 Change in critical micelle concentration (CMC) and aggregation number (N) with salt concentration for ionic surfactants

Surfactant

from Ref. [3].

sodium lauryl sulfate.Typically, sodium, potassium, or ammonium salts of fatty sulfonates with C8–C14 acyl chains tend to possess foaming and cleansing properties, and are suitable for use in shampoo-type applications. Anionic surfactants also assist in the dissolution or absorption of drugs. Bile salts in the stomach are anionic surfactants and play a critical role in food digestion [6,7]

2.2.3 Cationic Surfactants

Surfactants with a positive charge on their head group are called “cationic.” Examples of cationic surfactants include long-chain quaternary ammonium compounds (e.g., Dimethyldioctadecylammonium chloride). Some longchain quaternary surfactants show antimicrobial properties, and are used as preservatives in pharmaceutical formulations.

2.2.4 Nonionic Surfactants

These do not ionize in the presence of water, and generally have a low irritancy potential compared to ionic surfactants. The hydrophilic portion of the nonionic surfactant molecule could be an alcohol, polyol derivative, or esters of fatty molecules (waxes). Nonionic surfactants are widely used in pharmaceutical formulations.

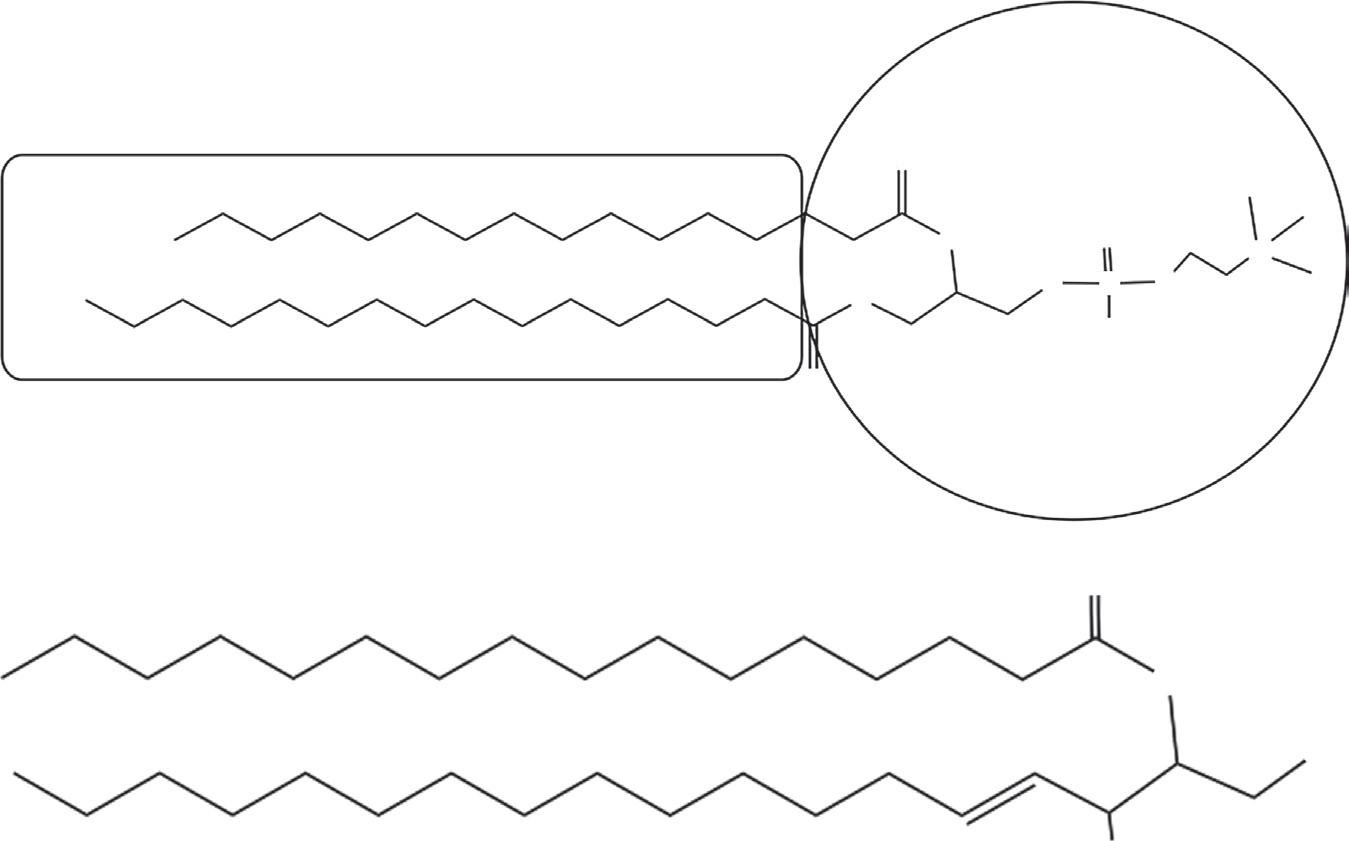

The structure of some of the synthetic surfactants are shown in Figure 2.3.

2.3 NATURAL SURFACTANTS

Surfactants are abundant in nature, and are present in both plants and animals. Some proteins behave like surfactants and play critical roles in various biological processes. An important group of protein surfactants

Data

Figure 2.4 (a) Structure of dipalmitoyl phosphatidyl choline (DPPC), a typical phospholipid. (From Kulkarni VS, Liposomes in personal care products. Delivery system handbook for personal care and cosmetic products. In: Meyer R. Rosen, editor. Technology, applications and formulations; in print 2005). (b) A type of sphingo lipid known as ceramide; several different types of ceramides (variations in N-acyl chain length) are present in stratum corneum of human skin.

Table 2.2 Critical micelle concentrations for lecithins with increasing acyl chain lengths

Lipids

Dibutanoyl lecithn

Dihexanoyl lecithin

Dioctanoyl lecithin

Dinonanoyllecithin

Dipalmitoyl phosphatidyl choline

Compiled from Refs [31]

CMC (mM)

80

14.6

0.265

2.87 × 10−3

2 × 10−8

precipitation before the drug is absorbed. In order to aid formulation development and assess which factors affect performance, standardized in vitro methods have been developed along with a system for classifying LBS formulations [15–17]. This classification is based on formulation components and their dependence on digestion to facilitate dispersion.

Five categories have been proposed; Type-I: drug mixed in triglyceride or glyceride formulations; Type-II: formulations additionally having lipophilic surfactants; Type-IIIA: fine emulsion–self-emulsifying formulations with hydrophilic surfactants and cosolvents; Type-IIIB: those that form microemulsions with surfactants and cosolvents; and Type-IV: formulations composed of surfactants and cosolvents.

Some of the lipid-based oral drugs in the marketplace are listed in Table 2.3 along with the surfactants or lipids used in their formulations.

2.4 THE ROLE OF SURFACTANTS IN PHARMACEUTICAL FORMULATIONS

Surfactants, by the virtue of their intrinsic property of reducing the surface tension of water and being amphiphilic in nature, have found various roles in pharmaceutical formulations and have been used in all dosage forms. Some of the surfactants used in different dosage forms as listed in FDA’s (U.S. Food Drug Administration) “Inactive Ingredient Guide” (IIG) database are shown in Table 2.4

2.4.1 Skin Penetration Enhancers

The primary function of the skin is to protect the internal organs from external invasion by forming a strong barrier between the outside environment and the body. However, for topical dosage formulations such as transdermals, penetration of the drug into the skin is essential. Therefore, transdermal/topical formulations need to act against the natural function of the skin [18] . Although the skin acts as a barrier, it is not completely impermeable. Chemical penetration enhancers and certain surfactants can be incorporated into topical/transdermal formulations to help facilitate penetration of the drug into the skin [19] . Fatty acids (e.g., oleic acid), fatty alcohols (e.g., myristyl or oleoyl alcohols), fatty esters (e.g., isopropyl myristate), lipids, anionic and nonionic surfactants are commonly used as chemical penetration enhancers. Although the use of surfactants can enhance penetration of the drug into the skin, they increase the risk of skin irritation. Consequently, skin irritation potential becomes a critical factor to be considered when formulating products for use on compromised skin. Formulations targeted for mucosal membranes (such as nasal, buccal cavity, vaginal, or suppositories) generally use nonionic surfactants as they are less irritating than ionic surfactants.

dosages are creams that are emulsions of oil and water phases. Other emulsion dosage forms including injectables, nasal sprays, and ophthalmic drops are available commercially. The selection of the surfactants to use and their concentration in the formulation are critical to making stable emulsions. A study of the oil-water interfacial tension as a function of surfactant concentration helps to determine the critical concentration of surfactant needed to achieve emulsification.

2.4.2.1 Hydrophile–Lipophile Balance (HLB) System

Surfactants are used to produce emulsions of oil droplets dispersed in water (oil-in-water) or water droplets dispersed in oil (water-in-oil). Consequently, emulsions have a large technological application, including in pharmaceutical dosages. An empirical but very useful numerical rating system was introduced by Griffin and is known as the Hydrophile–Lipophile Balance or HLB number [20]. In general, highly water-soluble surfactants have high HLB values and highly oil-soluble surfactants have low HLB values. HLB number ranges based on the solubility or dispersability of the surfactants are shown in Table 2.5

Generally, surfactants with an HLB in the range of 4–6 are water-inoil emulsifiers and 8–18 are oil-in-water emulsifiers. HLB values can also be determined experimentally as HLB = 20(1−S/A) in which S = saponification number of the ester and A = acid value of recovered acid.

HLB numbers for some common surfactants are shown in Table 2.6

2.4.3 Aerosol Formulations

Surfactants have been used extensively in aerosol formulations. Surfactants reduce the surface tension of water and thereby facilitate atomization of the formulation. For nasal spray formulations, the formation of uniform plumes depends not only on the device but also on the formulation.The use of surfactants in nasal sprays is common to achieve the effective delivered dose (proper droplet size and plume) [22]. The use of surfactants in topical aerosols (wound healing sprays or pain relief sprays) or foam formulations is also common.

2.4.4 Surfactant Gels

The formation of gels by small amphiphilic molecules (surfactants) is well documented [23–25]. Gel formation by surfactants is considered a process similar to micellization rather than crystallization. Poloxamers™ are polymeric nonionic surfactants of ethylene oxide and propylene oxide, and several varieties of Poloxamers™ are listed in the FDA IIG database for use in pharmaceutical

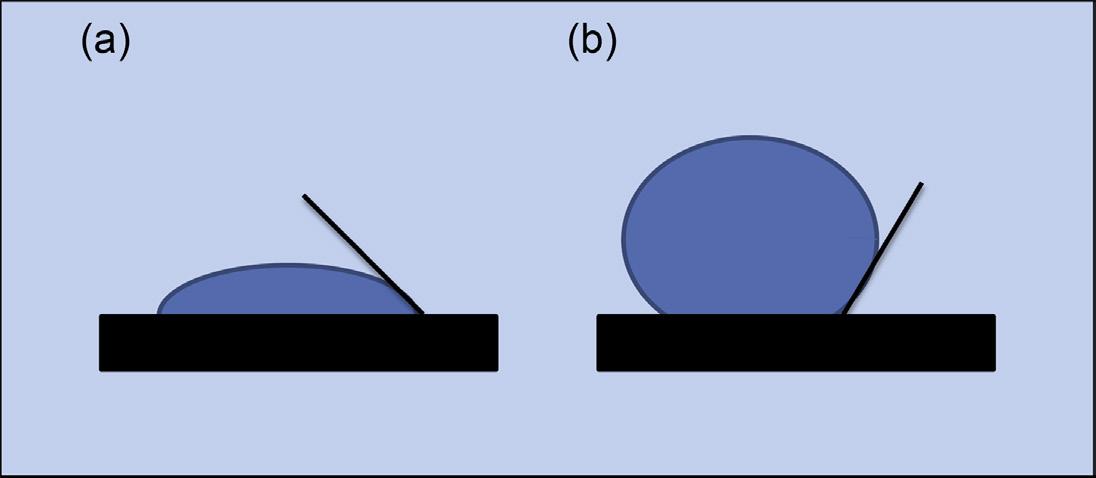

Figure 2.5 Contact angle of a water drop with a solid surface; <90° indicates wetting (a) and ≥90° indicates nonwetting (b).

2.6 CONCLUSION

Surfactants are ubiquitous in nature. Both natural and synthetic surfactants are used in pharmaceutical formulations. The FDA-IIG database lists numerous surfactants, indicating that surfactants are important excipients in all dosage forms. Surface phenomena including surface tension and contact angle studies play a critical role in formulation development, as well as in the design or selection of container closure systems for liquid dosages.

REFERENCES

[1] Fuhrhop JH, Koning J. In: Stoddart JF, editor. Membranes and molecular assemblies: the synkinetic approach. London: Royal Society of Chemistry; 1994.

[2] Fuhrhop J-H, Wang T. Bolaamphiphiles. Chem Rev 2004;104:2901–37.

[3] Ikeda S, Ozeki S, Tsunoda M-A. Micelle molecular weight of dodecyldimethylammonium chloride in aqueous solutions, and the transition of micelle shape in concentrated NaCl solutions. J Colloid Interface Sci 1980;73(1):27–37.

[4] Jones MN, Chapman D. Micelles, monolayers, and biomembranes. New York: WileyLiss; 1995. p. 68.

[5] Sidim T, Acar G. Alcohols effect on critic micelle concentration of polysorbate 20 and cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromine mixed solutions. J Surfactants Deterg 2013;16:601–7.

[6] Maillette de Buy Wenniger L, Beuers U. Bile salts and cholestasis. Dig Liver Dis 2010;42(6):409–18.

[7] Small DM. Size and structure of bile salt micelles: influence of structure, concentration, counterion concentration, pH, and temperature. Adv Chem 1968;84:31–52.

[8] Griese M. Pulmonary surfactant in health and human lung diseases: state of the art. Eur Respir J 1999;13(6):1455–76.

[9] Jones MN, Chapman D. Micelles, monolayers, and biomembranes. New York: WileyLiss; 1995. p. 8–10.

[10] Porter CJ, Trevaskis NL, Charman WN. Lipids and lipid-based formulations: optimizing the oral delivery of lipophilic drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007;6:231–48.

[11] Downing DT, Strauss JS.Variability in the chemical composition of human skin surface lipids. J Inv Dermatol 1969;53(6):322–7.

[12] Pappas A. Epidermal surface lipids. Dermatoendocrinol 2009;1(2):72–6.

[13] Pople PV, Singh KK. Development and evaluation of topical formulation containing solid lipid nanoparticles of vitamin A. AAPS PharmSciTech 2006;7(4):91.

[14] Kulkarni CV, Moinuddin Z, Patil-Sen Y, Littlefield R, Hood M. Lipid-hydrogel films for sustained drug release. Int J Pharm 2015;479(2):416–21.

[15] Cannon JB. Drug product development process for lipid-based drug delivery systems. Am Pharm Rev October 2012;15(6)

[16] Kalepu S, Manthina M, Padavala V. Oral lipid-baseddrugdeliverysystems – an overview. Acta Pharm Sin B 2013;3(6):361–72.

[17] Müllertz A, Ogbonna A, Ren S, Rades T. New perspectives on lipid and surfactant based drug delivery systems for oral delivery of poorly soluble drugs. J Pharm Pharmacol 2010;62(11):1622–36.

[18] Bos JD, Meinard MM. The 500 Dalton rule for the skin penetration of chemical compounds and drugs. Exp Dermatol 2000;9:165–9.

[19] Karande P, Jain A, Ergun K, Kispersky V, Samir Mitragotri S. Design principles of chemical penetration enhancers for transdermal drug delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102(13):4688–93.

[20] Adamson AW. Physical chemistry of surfaces. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc; 1990. p. 537–9.

[21] Barnes GT, Gentle IR. Interfacial science an introduction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 133.

[22] Kulkarni V , Shaw C . Formulations and characterization of nasal spray. Inhal Mag June 2012.

[23] Estroff LA, Hamilton AD. Water gelation by small organic molecules. Chem Rev 2004;104:1201–17.

[24] Raghavan SR. Distinct character of surfactant gels: a smooth progression from micelles to fibrillar networks. Langmuir 2009;25(15):8382–5.

[25] Patel HK, Rowe RC, McMahon J, Stewart RF. Properties of cetrimide/cetostearyl alcohol ternary gels; preparation effects. Int J Pharm 1985;25(2):237–42.

[26] Jouyban A, Fathi-Azarbayjani A. Experimental and computational methods pertaining to surface tension of pharmaceuticals. In: Toxicity and drug testing. In Tech; 2012. p. 47–70.

[27] Pecora JD, Guimaraes LF, Savioli RN. Surface tension of several drugs used in endodontics. Braz Dent J 1991;2:123–7.

[28] Sklubalová Z, Zatloukal Z. Study of eye drops dispensing and dose variability by using plastic dropper tips. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2006;32(2):197–205.

[29] Van Santvliet L, Ludwig A. Determinants of eye drop size. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49(2):197–213.

[30] Van Santvliet L, Ludwig A. The influence of penetration enhancers on the volume instilled of eye drops. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 1998;45(2):189–98.

[31] Kulkarni V. Liposomes in Personal Care Products. Delivery system handbook for personal care and cosmetic products. In: MR Rosen, editor. William Andrew Publishing, 2005, pp.285-302.

CHAPTER 3 Drug Delivery Vehicles

3.1

3.1 INTRODUCTION

As discussed in the introductory chapter, drug substances cannot usually be administered or applied directly to the body due to safety reasons. As a result, drug substances need to be either dissolved or suspended in a suitable matrix so that they can be safely injected, swallowed, or applied to the skin (either intact or compromised) or mucosal membranes. The matrix in which the drug substance is dissolved or suspended is considered a “vehicle” for carrying the drug to its intended target. If the drug substance dissolves in the formulation, the solvent (or solvent system) is the drug delivery vehicle. However, not all drugs can be delivered in the form of a solution because a large number of drug substances are poorly soluble in either water or water/cosolvent mixtures. In this case, the drug substance is suspended in a “structured delivery vehicle” (either solid-in-liquid or liquid-in-liquid). The most common structured-delivery vehicles are emulsions, gels, liposomes, polymers, dendrimers, solid–lipid nanoparticles, and composite nanoparticles and have been used for injectable/infusible liquids, subcutaneous gel injections, semi-solid topical products (e.g. gels, creams, lotions, ointments), and oral suspensions. An advantage of structured drug delivery systems is that the drug (whether hydrophilic or hydrophobic in nature) can be entrapped in the formulation matrix, and that this encapsulated drug can be formulated into a stable delivery vehicle such that the drug can be safely delivered to its target destination. Compared to systemic delivery, delivering the drug to the target site enables the dose of the drug to be lowered, thus reducing possible toxicity and side effects. Structured drug delivery systems can also be engineered for sustained drug release, drug release triggered by

external stimulus, and providing protection to the drug substance from degradation—thereby extending the shelf life of the drug product compared to unprotected formulations (e.g. simple solutions).

3.2 EMULSION DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS

Emulsions consist of two immiscible phases (oil and water). One of the phases is dispersed as droplets within the other phase, and the formulation is stabilized using a combination of surfactants, emulsifiers, and thickeners. There are two main categories of emulsions: macroemulsions and microemulsions. Macroemulsions are thermodynamically unstable and are kinetically stabilized using elevated temperature and high shear during the mixing process. Microemulsions are formed spontaneously in the presence of the appropriate concentration of certain surfactants and cosolvents. Oil-inwater macroemulsions that contain very small internal phase droplets (generally <500 nm) are sometimes called nanoemulsions. Suitable surfactants can be selected by matching the “required HLB (Hydrophile Lipophile Balance) number” of the oil to be emulsified with the HLB of two or more surfactants [1]. The Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is either dissolved in the oil or water phase, or it may be suspended in the formulation. An existing marketed product for intravenous infusion that is based on an emulsion-delivery system is Intralipid®, which is a nanoemulsion consisting of 10%, 20%, or 30% w/v soybean oil in water, and is stabilized with various phospholipids. It is practically isotonic with blood, has a pH of approximately 8, and a particle size of 200 – 500 nm.

Microemulsions have been described as optically isotropic/transparent and thermodynamically stable liquid solutions [2] consisting of water, oil, and surfactant. A generalized ternary phase diagram for the formation of microemulsions is shown in Figure 3.1. In many cases, cosurfactants and/ or cosolvents are needed to generate microemulsions. The particle size of microemulsions generally ranges from 5 to 50 nm. Microemulsions are sometimes called “micellar emulsions” [3] . There are four types of microemulsions:

Type I: the surfactant is dominantly soluble in water, resulting in an oilin-water (o/w) microemulsion.

Type II: the surfactant is mainly soluble in the oil phase, resulting in water-in-oil (w/o) microemulsion.

Type III: a “surfactant-rich” middle phase coexists with larger water and oil “surfactant-poor” phases, resulting in a three-phase system.

Figure 3.1 Ternary phase diagram showing microemulsion and macroemulsion regions (see Ref. [2]).

Table 3.1 Comparison of macroemulsions and microemulsions

Macroemulsion

Thermodynamically unstable

Kinetically stabilized

Appearance: Opaque, milky liquid

Particle size typically >0.1 μm (range 0.1–100 μm)

Shelf life could be up to 3 years

Low surfactant/emulsifier levels

Microemulsion

Thermodynamically stable

Formed instantly

Appearance: Translucent to clear liquid

Particle size typically <0.1 μm (range 0.01–0.1 μm)

Stable for very long time

High levels of surfactant, co-surfactants, or cosolvents

Type IV: a single-phase (isotropic) micellar solution, which forms upon addition of a sufficient quantity of surfactant and cosolvent.

For comparison between macro- and microemulsions, see Table 3.1.

3.3 LIPOSOME DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS

Lipids form spherical vesicles (known as liposomes) consisting of an aqueous core and a lipophilic bilayer enclosing one or more aqueous compartments. In solution, both the inner core of the liposomes and the continuous phase are aqueous, and the two aqueous components are separated by a