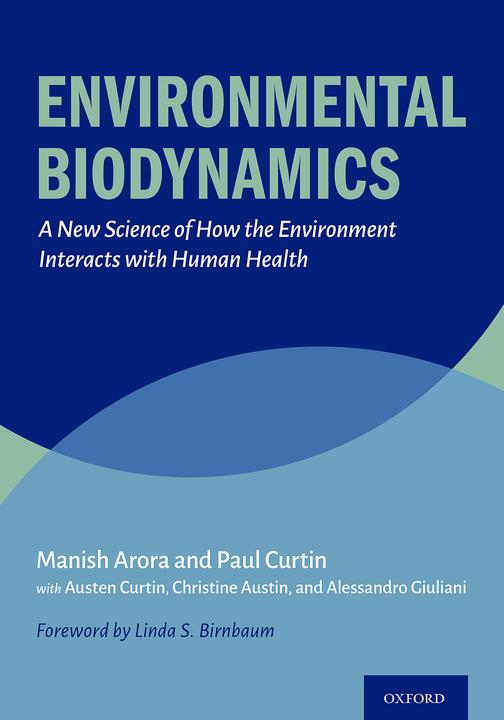

Environmental Biodynamics

A New Science of How the Environment Interacts with Human Health

Manish Arora Paul Curtin

With Austen Curtin

Christine Austin

Alessandro Giuliani

3

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Arora, Manish (Manish Kumar) author. | Curtin, Paul (Paul C. P.), author. | Curtin, Austen, author. | Austin, Christine (Christine Enid), author. | Giuliani, Alessandro, 1959– author.

Title: Environmental biodynamics : a new science of how the environment interacts with human health / Manish Arora, Paul Curtin ; with Austen Curtin, Christine Austin, Alessandro Giuliani. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021031355 (print) | LCCN 2021031356 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197582947 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197582961 (epub) | ISBN 9780197582978 (ebook)

Subjects: MESH: Environmental Medicine—methods | Precision Medicine—methods | Environmental Exposure—adverse effects | Environmental Pollutants—adverse effects | Time Factors Classification: LCC RA566 (print) | LCC RA566 (ebook) | NLM WA 30.5 | DDC 613/.1—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021031355

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021031356

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197582947.001.0001

This material is not intended to be, and should not be considered, a substitute for medical or other professional advice. Treatment for the conditions described in this material is highly dependent on the individual circumstances. And, while this material is designed to offer accurate information with respect to the subject matter covered and to be current as of the time it was written, research and knowledge about medical and health issues is constantly evolving and dose schedules for medications are being revised continually, with new side effects recognized and accounted for regularly. Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulation. The publisher and the authors make no representations or warranties to readers, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of this material. Without limiting the foregoing, the publisher and the authors make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or efficacy of the drug dosages mentioned in the material. The authors and the publisher do not accept, and expressly disclaim, any responsibility for any liability, loss, or risk that may be claimed or incurred as a consequence of the use and/or application of any of the contents of this material.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

For Arjun and Indra, and for Maddie, Kiran and Grace, and their mum, Catherine MA

For J., C., and R. Curtin and in memory of D. Gess PC and AC

For the tooth fairies all over the world that made this work possible, and to my own personal tooth fairies Ros and Kev CA

To my wife and my daughters: the poles of a never-ending love interface AG

Foreword

Complex systems cannot interact directly or exist in isolation. With this short and seemingly simple statement, Manish Arora, Paul Curtin, and their colleagues have written a marvelous book for those who are passionate about the environment. They have planted a seed for a bold idea that hopes to bring about an advance in the way we understand our relationship with our environment and how it impacts human health.

From 2009 and 2019, I served as the Director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the preeminent governmental funding agency worldwide for environmental health research. During my tenure I provided leadership and management to thousands of governmentsponsored research projects that have greatly enriched human knowledge on environmental health, a field that complements genomics in exploring the determinants of health and disease. I often stressed that nothing is just genetics and nothing is just environment, but our health is a combination of both contributing factors.

One inspired project was from a young scientist who had completed an eclectic PhD spanning oral pathology, nuclear physics, and analytical chemistry. He proposed a unique idea—that teeth were akin to our body’s “hard drives” or the history of a tree’s life is reflected in its growth rings. He believed that by determining chemicals along the growth rings in teeth he could build a “map” of a person’s history of exposure to various environmental exposures, including those that happened before birth. That scientist, and dentist, was Manish Arora. From those early days as a postdoctoral trainee, he became the first NIEHS recipient of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director’s New Innovator grant for environmental health sciences and was awarded a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE), the highest honor the United States bestows upon early career scientists and engineers, by President Barack Obama. At that point, I invited Manish to give the plenary lecture before the NIEHS Advisory Council. He emphasized that time must be placed at the core of the gene-by-environment understanding of health; just as Newton’s and Einstein’s theoretical work propelled physics

x Foreword

into new frontiers, environmental health sciences required some fundamentally new approaches to bring about a bold new frontier. Four years later, I was thrilled to see that Manish and his distinguished colleagues have realized that vision and proposed a new theory (the biodynamic interface conjecture) and a novel subfield of environmental health sciences—Environmental Biodynamics.

Having had the pride of guiding Manish in his career from a trainee to a full professor, I was honored when Manish asked me to write the foreword for this book. In the simplest terms, this is a book full of fearless ideas, a book that makes the reader wonder how the universe is so diverse but at the same time organized by essential rules, and most importantly, it asks if there are similar fundamental rules that govern how our environment shapes our lives. This book also argues against the reductionist trends that have crept into medical research that have attempted to study our environment and our physiology by breaking them into ever-smaller constituent parts. Instead, Arora and colleagues propose a new elegant view of examining the choreography of interacting systems by considering the whole rather than just the parts. In a recent editorial, published in the journal BioEssays, 1 the theory espoused by Arora and Curtin was described as follows: Although we can describe how a human system, such as the endocrine system, works, and likewise the chemical nature of compounds present in our environment; but the result of the interaction is more than a simple combination of the two knowledge sets: We need to study not only the components of a complex system but also the processes that create the phenomena that we witness as a result of this interaction. This is the “biodynamic interface,” and it is a conceptual structure that comes into being upon interaction of the component entities; it is a new way to study interactions in complex systems and better understand emergent phenomena. The authors not only make this theoretical argument but have also provided data on how their ideas can be implemented in practice.

This book is strewn with little gems—there is a puzzle for readers to show how a dynamic system may be mistaken for a static one entirely because of our point of view; a famous painting by Marcel Duchamp reveals how time can be placed at the center of our worldview; a poem that conveys the usefulness of “nothing;” and an example of how the chemicals in our blood, such as cholesterol or zinc, actually move in orbits the same way planets do. The passion and effort of the authors become clear through these vignettes and the various sections that provide historical and philosophical context, but it is also

Foreword xi

clear that the writers desire to share knowledge and be good teachers as they provide tools throughout the book for other researchers and practitioners. It is my hope that this book will be read widely by students of environmental health sciences and others generally interested in the environment. This work reflects a passionate effort to refocus our profession’s view on the importance of time and complexity, to move away from reductionist perspectives that have entrained past generations to envision environmental inputs through static measurements, and to place environmental sciences at the core of the practice of medicine. And, along with the authors, I share my hope that just as Environmental Biodynamics is a first step to a bold new frontier in environmental sciences, there will be many more.

Linda S. Birnbaum,

PhD Scientist Emeritus and Former Director, NIEHS and National Toxicology Program Scholar in Residence, Duke University

Reference

1. Arora, M., Giuliani, A., & Curtin, P. (2020). Biodynamic interfaces are essential for human–environment interactions. BioEssays 42, e2000017, doi:10.1002/ bies.202000017.

Preface

We are setting forth a new discipline in science, one that we have named Environmental Biodynamics. We have done so to recognize that our focus is on the environment and its relationship with our biology, and the key to understanding this relationship is the constant change (or dynamics) of these complex systems. We have also taken a step that is unusual in environmental health sciences—of proposing a new theory, the biodynamic interface theory. Our collective desire to write this book arose from a shared acknowledgment that many current practices in environmental health sciences needed to be examined through a critical lens—that it was time to leave behind the comfort of opinion and start afresh by questioning decades of dogma. This book is written in the background of the global COVID-19 pandemic, severe weather events driven by climate change, and an upheaval in our social and political systems. All these events only reinforce the importance of our physical and social environment, and how we, as a species, treat this planet. With this in mind, my colleagues and I have written a book that argues for a new, more daring way to look at our environment and its relationship with human health. Writing this book has been a privilege. I (Arora) was fortunate to be working with friends and colleagues who, like me, are a collection of “atoms with curiosity” (as Richard Feynman put it). There are many people to thank, but I want to start with the unsung heroes of science—the taxpayers who put their faith in us scientists to move the needle forward on the sum total of human knowledge. None of this work would be possible without the generous support of the custodians of federal research funding—the National Institutes of Health of the United States, and especially the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. In particular, I thank Drs. David Balshaw, Kimberly Gray, Gwen Collman, and Linda Birnbaum for being champions of academic science. I also want to thank my department chair, my colleague of 16 years, and my friend, Dr. Robert (Bob) Wright, for always supporting my work. I have had the privilege to work with many brilliant scientists, including Dr. Rosalind Wright at Mount Sinai, Dr. Andrea Baccarelli at Columbia University, and Dr. Erin Haynes at the University of Kentucky. They have

xiv Preface

been inspirations. To my closest collaborators, Drs. Sven Bölte in Sweden, Shoji Nakayama and Miyuki Iwai in Japan, Martha María (Mara) Téllez Rojo in Mexico, Andrea Cassidy-Bushrow at Wayne State University, Tanya Smith at Griffiths University, and Renaud Joannes-Boyau at Southern Cross University, thank you for the camaraderie. I also want to thank Lisa Maroski for the many deep and thoughtful discussions at the beginning of this journey. Lastly, but not least, I thank Jill Gregory, medical illustrator at Mount Sinai, for creating all the beautiful artwork for this book.

1 Introduction to Environmental Biodynamics

Introduction

Every day around the world, at the behest of medical professionals, millions of needles are pushed into human veins, and drops of blood are sucked into tubes that pass through highly skilled hands and the most technologically advanced machines to identify components and characteristics of the blood in the form of test results—a set of numbers that is compared to ranges of “normal” values. Presumably, these digits signify the health of various parts of our body, such as the liver, the kidneys, and so on.

Recently, one of those blood draws was mine (Arora); for my annual physical exam, my doctor ordered a complete blood workup—white and red blood cell counts, cholesterol and glucose levels, and about 30 other values. This workup has become a yearly game for us, like darts, to see if my numbers are on target; that is, within the corresponding normal range. Putting aside for now questions about what makes a value “normal” and how those ranges are established, let’s consider what one number on one day at one time represents. It’s a snapshot; it captures the state of my blood at one moment of my entire life. And, like snapshots, if lots of other factors (such as background lighting and shutter speed for photographs) aren’t also just right, then the snapshot might not be a good likeness of me. Snapshots lack important qualities that are inherent in how we perceive the world; they ignore the moments that came before and after and everything else that happens out of frame.

This visit with my doctor made me think of a musical game my wife plays with my triplet daughters on long road trips. My wife hums a song and our daughters guess the name. If they cannot guess it, their mother hums a longer piece of the song until enough notes (in the proper order) allow the melody to

Environmental Biodynamics. Manish Arora and Paul Curtin with Austen Curtin, Christine Austin, and Alessandro Giuliani, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2022. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197582947.003.0001

become obvious. It would make no sense to play this game if my wife only hummed one second of one note of the song. Music only sounds like music because of how its components change over time and because of the dependence of the notes to come on those that have passed.

We can imagine our bodies as an orchestra of many organs and tissues and their cells, each humming complex rhythms but all working together in harmony, a harmony that has been refined by millions of years of evolution. How would we ever know what the symphony made by this orchestra sounded like if we only did one blood test every year? How could this snapshot capture the dependency of each signal in that moment on all the moments that have passed? What if a signal was playing the right “note” in the moment, but was otherwise out of sync with the rest of the orchestra?

A few years earlier I had taken my infant daughters to the pediatrician, and they underwent what is now standard practice, at least in New York—a blood test for lead, the toxic metal that has been linked to many neurobehavioral problems. Remembering my children’s fingers being pricked for a drop of blood made me wonder again about that biological orchestra. With all the different substances in our body—the calcium that makes our bones strong, the zinc that helps with immune function, and the hormones that help us mature—what happens when a bad player, such as lead, joins this chemical orchestra? Does it change the rhythm of the whole ensemble, does it play out of sync by itself and leave the other musicians unperturbed, or does it stop the other chemicals from playing altogether?

From these humble beginnings my colleagues and I began a quest to understand how humans and the environment interact and if there are universal rules underlying those interactions. Can we find evidence of such a symphony, and measure its performance as we do with the “notes” of each individual signal? Is there a central theory, like the theories that explain apples falling or why time slows down when we travel faster, that also governs how human physiology interfaces with the environment?

This four-year journey led me to seek the help of scientists and thinkers from different walks of life who originate from the United States, Australia, Ireland, Italy, and India. Each brings her or his own perspectives to the question: Is there an underlying theory that explains how humans and our environment interact? This quest led us down many paths, from biology and environmental sciences to theoretical physics and mathematics, even to linguistics, philosophy, and art. The fruit of our labors is a new field of inquiry, which we call Environmental Biodynamics. It offers a novel approach to understanding the

connections between our physiology and our world—a first step, but by no means the last, in devising a theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between our environment and us.

In our journey to formulate a new perspective on the interaction between the environment and human health, at times we found ourselves with no prior work to cling to, and so we had to lay down the scientific foundations ourselves and then build upon them. At other times we were fascinated and humbled by the work of others and have indicated where we have followed their paths. These words of Denis Noble resonated with me: “there is, a priori, no privileged level of causation,”1 as did the propositions in Laurent Nottale’s work on scale relativity and fractal space-time—namely, that there are no privileged levels of scale. 2 Like our work, they have argued so eloquently against the reductionist approaches that have come to dominate scientific inquiry in medical research and assume that measuring something at smaller and smaller scales is somehow going to provide a better understanding of our physiology.

This problem has only increased with recent advances in genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and other -omic technologies that have propelled the exploration of biology by providing tens of thousands of measures, but almost always as static snapshots. These often-superficial applications of systems theory have neglected the consideration of the fundamental questions that spurred the genesis of the field, which focused on how life is organized and how it functions. Instead, we have created an “ocean of correlation” with an unrelenting modern emphasis on digging deeper and crunching harder, as if including more -omics data and the brute force of supercomputers would miraculously reveal the secrets of how and where we belong in our world. To this end, I found solace in Alfred North Whitehead’s notions of the “myth of substance and the fallacy of misplaced concreteness,”3 because I no longer felt alone in rejecting the view of human physiology and our environment as a collection of things assembled together. Extending from this rejection of “thingness,” I always have found it difficult to accept (and I continue to do so) that the “selfish gene” is the main reason why the world is the way it is or why we are the way we are.

Throughout this book my coauthors and I encourage readers to consult other important texts that will enrich their understanding of the topics we weave together. Furthermore, for us it is not enough simply to propose a new field of inquiry or provide a new theoretical foundation; we also see the need to provide tools for others to operationalize Environmental Biodynamics. For this reason, we provide chapters on how data can be collected on the

dynamic nature of our physiology and discuss computational methods to analyze those data.

Finally, we also recognize that the principles underlying this new field are themselves dynamic, and our perspective must evolve. Our aim is to identify the key principles that scientists will need to build a platform upon which others will stand to advance a better science, one that inspires new ideas, new questions, and new hypotheses. After all, isn’t that the ambition of all scientists—to contribute a verse (as Walt Whitman said)4 so that in time the next verse can be written? Toward this end, we call our colleagues to action and ask for the establishment of the field of Environmental Biodynamics that places the constant change of our physiology and our environment at its core, at the correct dimensions of space and time.

What to Expect from This Book

There are many wonderful works that discuss the benefits of healthy lifestyles, such as eating organic food, avoiding certain chemicals, or spending more time in green outdoor spaces; all of those instructions are valuable products of decades of health research. However, this book takes a different route by asking deeper questions to uncover the universal truths underpinning the most important driver of the health of individual humans and human society—our environment. Think of it like this: Isaac Newton did not help us understand how to farm and harvest apples but why and how apples fall to the earth; similarly, we do not discuss how to live a healthy life but why and how the environment influences human health. In the process, we will formulate and present evidence for a new theory and a new scientific field that arises from that theory.

This book is for those who are passionate about the environment, partake in environmental or biomedical research, and/or teach environmental medicine. As such, it is written at multiple levels of complexity; some parts provide a general introduction that is accessible to all readers, and other sections take a deep dive into theories, laboratory methods, and mathematics that are of more interest to scientists actively engaged in this field. We use boxes throughout the book to provide background supporting information relevant to the topics we discuss. We will indicate where we zoom in to technical details so that readers can choose to skip those sections if they are beyond the scope of their interest. We also promise the reader that when we propose a theoretical advance, we

will back that claim with real data. And when there are no data, we will clearly indicate the next steps needed to confirm or disprove our proposition so that other scientists may join us on this journey. Each chapter of the book is meant to stand alone to some degree, which is why there are regular “recaps” of material covered in previous chapters so that the flow of our discussions is not interrupted for the reader.

Aims and Scope of Environmental Biodynamics

In emphasizing the need for a new theoretical perspective to guide thinking in environmental health sciences, we have so far neglected some minor points, including: What theory do we need, exactly? And what aspects of our environment and our health should it address? These topics are naturally the focus of this book, but we will first address the general scope of topics that our approach, Environmental Biodynamics, seeks to address.

First, we intend to shift the fundamental perspective on the complexity of environmental-biological interactions from the current dogma, which embraces an ever-widening taxonomy of structural relationships, and instead focus our understanding on functional interdependencies. In this view, complexity is not a nuisance that obfuscates or obscures our measures or interpretations; rather, complexity itself is what we seek to measure. And while doing so we place that most important of dimensions—time at the core of how we understand the relationship between the environment and human physiology.

Second, we aim to challenge an assumption that is taken as doctrine by many—that complexity should be analyzed and understood at the level of the population or group. This sort of thinking is pervasive in environmental medicine, and not without reason; but, we argue, the time has come to integrate advances in computational and biochemical sciences to finally actualize the promise of precision medicine by studying complexity at the level of the individual.

Last, we seek to illustrate the role that constraints play in the measurement and assessment of biological systems, and while doing so we aim to provide new tools to reorient the scientific gaze. Our ultimate goal is to provide a new perspective to organize our study of environment, health, and medicine; to provide, in other words, a new set of questions to ask.

Box 1.1 Structural and Functional Perspectives

One of our goals is to shift the current paradigms in medicine and related sciences, which are predominantly structural, to a combined structural and functional perspective. The structural perspective focuses on specific aspects of physiology and views them as “things” (organs, molecules, drugs) and focuses on the “what” and “how much” of the environment influences physiology (e.g., which toxin and how much of it causes specific symptoms or a disease, which drug and how much will help alleviate a specific condition). The functional perspective, on the other hand, attempts to understand our physiology by focusing on the process of interdependence; specifically, how do interactions that underlie our physiology develop over different timescales, and how do such changes interact with the ever-changing environment? Extending the music analogy mentioned earlier in this chapter, in an orchestra, as one musician is joined by another musician, they each play differently to accommodate the various dynamic aspects inherent in their instruments (for example, a piccolo cannot play the same notes as an upright bass). This then results in a more complex piece of music. This dynamic process of bidirectional interaction and synchronization continues until a harmonious composition is reached. This body of music is, thus, dependent on both the structure and the function of the musical instruments, and the same is true for our physiology.

Complexity and the Need for Precision Environmental Medicine

We need first to understand what is said, and what is meant, when the word “complexity” enters the conversation of environmental medicine. From a standard epidemiological perspective, complexity is a challenge that emerges when we are trying to solve a research problem. And though we say a problem, really it is almost inevitably always the problem: Does this thing in the environment—maybe too much of a toxic chemical, or too little of a nutrient—relate to human health? Thousands upon thousands of studies, often very nice studies, have been published to answer this exact question, with the specific aspect of health being studied varied each time—maybe brain development in one study, maybe cancer rates in another—just as the specific environmental factor is likewise varied. Complexity, here, is not at the level of the research question, but rather in all the things that make answering that question difficult. Perhaps the toxic chemical has a greater observable effect in one sex, for example, or perhaps we are only sensitive to that exposure

when we are children, or the effects are dependent on the dose of the environmental agent. These sorts of challenges are solved with good study design, which in this context means collecting enough samples to deal with this complexity, planning in advance to measure and account for other relevant factors (some would refer to these as “confounders”), and having a statistical analysis strategy in place to model those variables.

Complexity is therefore intrinsic to environmental medicine, and always has been, but notice that this complexity arises along the journey of a research study and is dealt with in the solution to a research problem; it is never, in itself, a tool we use in deciding what question to ask. One of the pioneers of information science, Warren Weaver, saw the scope of this problem and sought to clarify the types of problems that science investigates. In his seminal paper of 1948 called “Science and Complexity,” he proposed three classes of problems— those characterized by organized simplicity, disorganized complexity, or organized complexity5 and outlined how these processes can be leveraged to better understand complexity (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Warren Weaver’s three classes of complexity. In an organized simplicity assumption, a change in one system can be fully explained by a change in another system. Biological systems rarely behave in this manner; inevitably, the number of factors involved, and the complexity of their interactions, precludes such direct exchanges. The disorganized complexity scenario assumes a probability-based construct that works on group averages. For example, it provides the average behavior of a group of patients but cannot explain adequately how the environment impacts a particular patient. Organized complexity is where this explanation can be found. By focusing on time-dependent patterns we can unravel the bidirectional interaction between systems and operationalize interventions at the level of the individual.

The first class, organized simplicity, refers to simple, direct relationships between two systems. This commonly emerges when change in one variable is driven directly by change in another; for example, assuming a circuit of constant resistance, a change in electrical current will yield a corresponding change in voltage. A problem in the realm of organized simplicity can be solved with simple classical quantitative methods (such as a linear, nonlinear, or differential equations). The parameters in the preceding example of an electrical circuit could be solved by Ohm’s law (current = voltage/resistance), for example. Organized simplicity nonetheless does not imply that the problems are simple, in themselves. Rather, it merely implies that the relationships in a system governed by organized simplicity are simple or can be simplified. Putting a human on the moon was quite complicated, for example, but it falls into this class of problems because we can directly relate the movement of the earth to the movement of the moon and plot a spaceship’s course between them. In part this was because, though the earth and moon are themselves complex systems, and are further subject to more complex forces from the wider solar system, their relative motion and direct interaction could be effectively modeled by treating each as a simple point mass in a differential equation. Weaver suggests that prior to 1900, most problems in the physical sciences were addressed in this way, either through the consideration of only a few variables or through the simplification of systems to equivalent processes. In the last century, particularly following the advent of quantum physics and Schrödinger’s uncertainty principle, more sophisticated perspectives have emerged in physics and related physical sciences. But biological studies, generally, and environmental medicine, particularly, have been slow to embrace this shift.

Weaver identified a second class of complexity—disorganized complexity in the organization of physical and biological systems. Disorganized complexity emerges in systems that are characterized by simple, direct relationships, as in organized simplicity, but that involve the interaction of many disparate elements. In such cases the methods used to solve problems of organized simplicity break down (or become exponentially difficult) when there are more than a few variables. It would be easy to calculate the trajectories of two billiard balls, for example, but it would be very difficult, even with modern computational capacities, to calculate trajectories for all of them. However, and rather counterintuitively, if you have a thousand billiard balls, the problem becomes easier because you can characterize their behavior in other general ways by statistically analyzing their overall or average behavior. In fact we face this problem on a daily basis both in practical and scientific pursuits; we cannot possibly

measure or predict the motion of individual gas molecules, for example, but we can easily characterize the average behavior of a gas molecule through measures of kinetic energy such as the temperature of that volume of gas.

Instead of using classical mathematics, problems of disorganized complexity thus require a more statistical probability-based approach to solve them. Rather than characterize the motion of any given individual, we seek to characterize the distribution of the population—by measuring its average, its variability, and its consistency among other group-level parameters. The caveats for this type of problem, however, are that you must have a large number of the same type of thing (a large number of atoms of a gas in an enclosed volume, for example) and their behavior must occur at random (the technical term is stochastic). Characterizing the temperature of a given volume is less meaningful, for example, if one group of molecules has more energy than another. Thermodynamics is naturally a good example of this style of reasoning; we can measure emergent qualities of liquids and gases, such as temperature or pressure, without delving into the microscopic details of each molecule. Paradoxically, this approach is more precise the more numerous the “things” being analyzed, though with each addition we have another characteristic that we cannot evaluate directly but rather only estimate at a group level.

The properties of disorganized complexity, as with organized simplicity, are commonly assumed and leveraged in studies of environmental medicine. The assumption of stochastic processes, for example, is one reason epidemiologists value larger sample sizes (studies with more participants). However, this approach is reaching its limits because the urgent need in medicine is not really about the average behavior of a group; rather, it is quite the opposite—in addition to group behavior, we also need to know the individual’s exposure to specific environmental factors and how their physiology is responding to those environmental inputs. Weaver gave an appropriate example in his seminal paper of how this approach works—“it makes possible the financial stability of a life insurance company. Although the company can have no knowledge whatsoever concerning the approaching death of any one individual, it has dependable knowledge of the average frequency with which deaths will occur.” This is the very problem we are facing in environmental medicine: A reliance solely on epidemiological approaches tells us what is happening in a population on average terms, but when we visit our doctor, we want to know what is happening to us specifically, which is what precision medicine asks of us (see Box 1.2 for a brief description of Precision Medicine).

Box 1.2 A Brief Note on Precision Medicine

Precision medicine argues against a one-size-fits-all approach to the practice of medicine. Rather, it takes into account individual differences in patients’ genes, environments, and lifestyles. In this manner, medical decisions, treatments, practices, or products are tailored to specific subgroups of patients based on their genetic, molecular, or cellular profile. The perceived benefits of precision medicine are to more accurately predict which treatments will be most effective and safe, and possibly how to prevent the illness from happening in the first place. Environmental Biodynamics aims to impact the practice of precision medicine by placing temporal dynamics of our environment and our physiology at the center of medical practice.

The third realm of complexity that Weaver proposed—organized complexity characterizes systems that emerge in a sort of “middle kingdom”; these involve more elements and more complex interdependencies than could be summarized through organized simplicity, but there are fewer elements, which interact through nonrandom processes, to be consistent with disorganized complexity. Weaver describes complex organized systems like this: “They are all problems which involve dealing simultaneously with a sizable number of factors which are interrelated into an organic whole” [italics added]. Organic wholes tend to grow, develop, and self-organize, yielding hierarchical systems spanning multiple levels of organization. Consequently, the results are highly context-dependent, which gives rise to the information crisis that environmental medicine is now experiencing. Weaver recognized over 60 years ago that this middle kingdom was the 21st century’s frontier of basic science.6 Since then, mathematical techniques have been and continue to be developed to characterize organized complexity (we use them in Chapter 3 onward and describe them in detail in the appendix).

Weaver claimed that when dealing with complex organized systems, the focus of the investigation shifts from detailed analysis of single elements to perceiving the pattern underlying the connections among those elements; in other words, the interrelationships among the components. This approach pinpoints exactly one of the aims of Environmental Biodynamics: Our goal is to shift the focus of environmental medicine to organized complexity rather than organized simplicity, which treats complexity as a nuisance, or disorganized complexity, which ignores dynamic interdependency (see Figure 1.1). And while doing so, we extend Weaver’s work by placing time at the core of our approach to studying environment–human interactions.

Contrasting Environmental Biodynamics and Other -Omic Sciences

We are sure the readers have had had their doctor tell them how high (or low) their body mass index (BMI) or their blood cholesterol levels are in relation to a range of normal values (and the same would be true for many other parameters). Consider this, though: Have you ever been told the “stability,” “complexity,” or “entropy” of your BMI or your blood cholesterol? We believe that is exactly what medical tests should be reporting to you (and, in Chapter 3, we will show how it’s actually done).

Over the past two decades there has been a rise of the so-called -omic sciences: genomics, metabolomics, proteomics, and many others. While the data we present later in this book are generated on laboratory instruments that are also used by -omic scientists, the interpretation is different. In Figure 1.2 we show how Environmental Biodynamics is, in a manner of speaking,

Trajectories

Environmental Biodynamics

Substance-based disorganized complexity

Process-based organized complexity

Figure 1.2 Contrasting Environmental Biodynamics with -omic sciences. Current approaches that characterize environmental exposures use measures of concentration and intensity to measure “things” and lead to interpretations embedded in disorganized complexity. Environmental Biodynamics seeks to measure and characterize “processes” to provide an explanation based in organized complexity.

Orbits