1

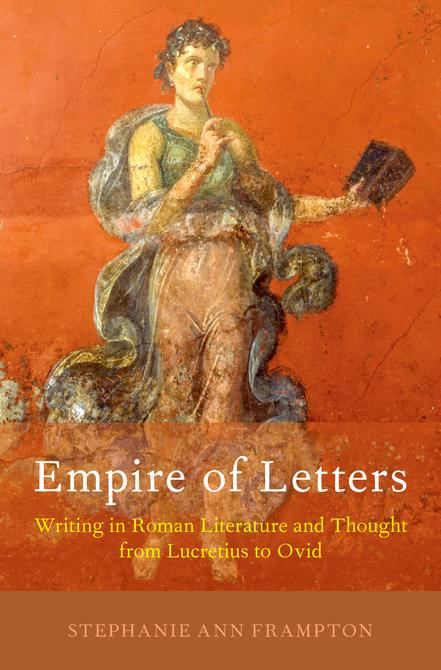

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stephanie Ann Frampton, author.

Title: Empire of letters : writing in Roman literature and thought from Lucretius to Ovid / Stephanie Ann Frampton.

Description: Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018014534 (print) | LCCN 2018016152 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190915421 (epub) | ISBN 9780190915414 (updf) | ISBN 9780190915438 (oso) | ISBN 9780190915407 (bb : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Latin literature—History and criticism. | Writing in literature. | Writing—Rome—History.

Classification: LCC PA6003 (ebook) | LCC PA6003 .F735 2018 (print) | DDC 870.9/001— dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018014534

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For my parents

List of Figures ix

Acknowledgments xi

Introduction: More than Words 1

1. Classics and the Study of the Book 13

2. Writing and Identity 33

3. The Text of the World 55

4. Tablets of Memory 85

5. The Roman Poetry Book 109

6. Ovid and the Inscriptions 141

Conclusion: Texts and Objects 163

References 171 Index 195

Figures

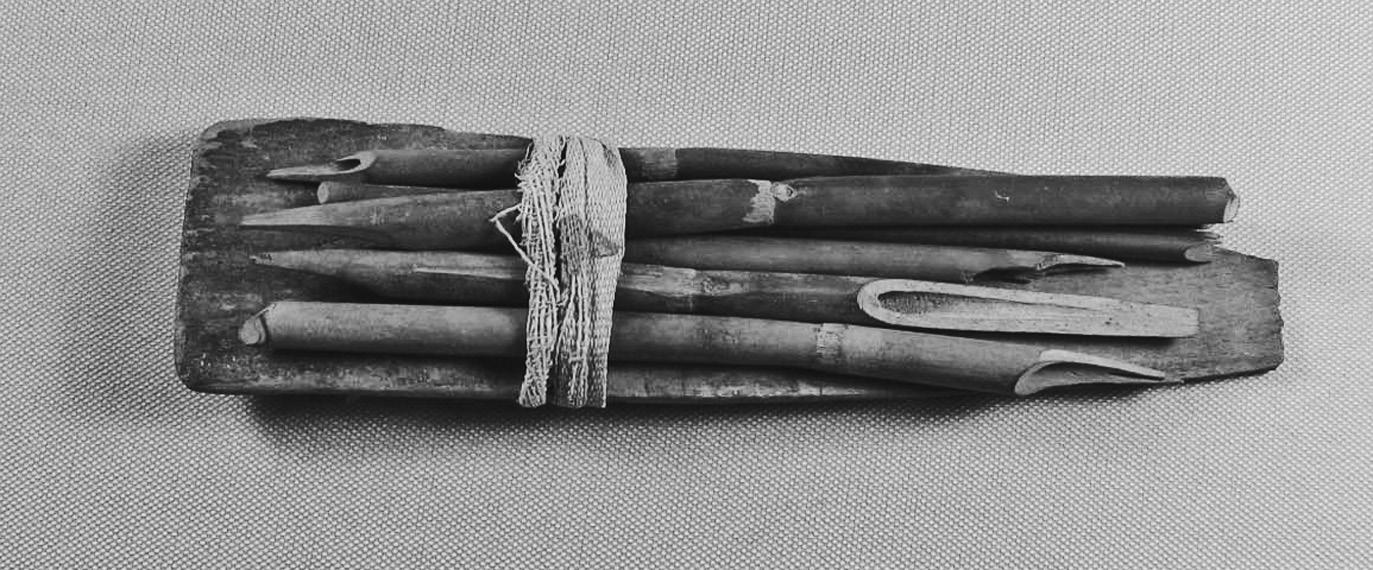

1. Five reed pens bound to a board with a small piece of linen. Ptolemaic Egypt. Brooklyn Museum 37.451E. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum. 3

2. Diagram of an ancient bookroll. Reproduced from Johnson (2009), 260, fig. 11.2. 15

3. Latin letter in papryus from Suneros to Chios. Oxyrhynchus, Egypt. 30 bce–14 ce POxy 3208. Courtesy of the Egyptian Exploration Society. 24

4. Wooden board with school exercises. Ca. fouth century ce, Egypt. PMich 763. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library. 68

5. Graffito syllabary from the nypheum of the House of Neptune and Amphitrite, (V, 6/7e), Herculaneum, Italy. Before 79 ce. CIL 4.10567. 84

6. Diptych writing tablets of wood with ivory hinges from the shipwreck off of Uluburun, Turkey. Ca. 1300 bce. Courtesy of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology. 86

7. The Muse Calliope holding writing tablets. Wall painting from the Inn of the Sulpicii, Murecine, Italy. Before 79 ce. Copyright Pio Foglia/–Fotografica Foglia SAS. 87

8. The “Gallus Papyrus.” Egyptian Museum of Cairo PQasr Ibrîm 78-3-11/1. Reproduced from Capsasso (2003), 123, tav. 6 by kind permission. 110

9. Composite detail of Rodolfo Lanciani’s 1901 Forma Urbis Romae showing the approximate locations of the public libraries in central Rome. Copyright the Open Forma Urbis Romae (2012). Developed by

the University of Oregon, Stanford University, and Dartmouth College (http://mappingrome.com/). Courtesy of the University of Oregon. 142

10. Greek epigram on papyrus from an Arsinoite miscellany. Egypt. First century ce. PLond 256 b (recto). Courtesy of the British Library. 164

Introduction

More than Words

The pen is ready, the ink is mixed, even the paper is polished: now let me begin.1

Cicero Letters to Quintus 2.14.1

Toward the end of July 54 bce , the orator, lawyer, and sometime politician Marcus Tullius Cicero picked up pen and papyrus. He was writing to his younger brother, Quintus, then in serving Gaul as a general in the army of Julius Caesar that was advancing toward Britain. The elder Cicero wrote that day from Rome about walking a political tightrope to stay in the good graces of both Caesar and Pompey, about the high rate of interest in the Forum, and about bribery in the election campaigns for the year’s tribunes and his friend Cato’s attempts to thwart it. 2 As he began, Marcus Cicero had all the necessary materials at hand: a reed pen freshly cut, some solid ink ready mixed with water, a sheet of papyrus burnished with ivory to make its surface smooth and bright. An auspicious start, perhaps. But Cicero says why he makes such a fuss: his last letter to Quintus had been less than perfectly legible. “You write that you were hardly able to read my previous letter. Brother, it was for none of the reasons

1. Cicero Q Fr. 2.14.1: calamo et atramento temperato, charta etiam dentata res agetur. My rather loose translation. Throughout the book, short translations are typically my own and longer ones sometimes are. Where I have used others’ translations, I have tried always to indicate the sources. Further information about editions and translations and abbreviations can be found in the References.

2. These were precarious times: within a little more than a decade, all five men— Pompey, Cato, Caesar, and both Ciceros—and many hundreds of others were to be assassinated or forced to commit suicide in the turmoil of civil war.

which you suppose, for I was not busy or bothered or angry with anyone. It is just that whatever pen comes to my hand, I treat it as if it were a good one.” 3

Good pen or bad, the vagaries of writing a letter in the first century bce were numerous. Reed pens and papyrus were imported from abroad and could be costly or of poor quality.4 When authors say anything about their writing tools, as Cicero does here, it is often to express annoyance. Pens needed to be sharpened regularly (Figure 1). It’s likely Cicero’s previous one had been dull. The grammarian Quintilian bemoans the fact that the frequent need to dip the nib in ink disrupted one’s train of thought.5 The poet Persius, imagining himself a student again, complains of ink sticking to the tip: “How can I study with a pen like this?”6 Horace even warns that pens could be blamed for their user’s lack of talent.7 Papyrus, too, was a source of trouble. According to Pliny’s Natural History, certain kinds of papyrus paper were too thin to stand up to fine pens and tended to tear or allow pigment to bleed through.8 He writes of a papyrus shortage under Tiberius that he says would have “sent life into chaos” had it not been managed by the senate.9 On the other hand, once you did manage to send a letter off, there was no guarantee that it would reach its destination. In the same summer that Cicero was corresponding with Quintus in Gaul, his friend Atticus wrote from Greece to complain that he had received no reply to an earlier letter: one of Cicero’s had gone astray.10 Anticipating hazards, Cicero sometimes sent several copies of important notes with different carriers or wrote them in code in order to frustrate unscrupulous ones.11 Although at the

3. Cic. Q Fr. 2.14.1: scribis enim te meas litteras superiores vix legere potuisse. in quo nihil eorum, mi frater, fuit quae putas. neque enim occupatus eram neque perturbatus nec iratus alicui. sed hoc facio semper ut, quicumque calamus in manus meas venerit, eo sic utar tamquam bono.

4. Harris (1989), 193–6, esp. 194 n. 104, on the expense of papyrus; though Winsbury (2009), 18–20 argues that claims of expense are overstated. Lewis (1974, with 1989) is the standard history of its trade. The most extensive ancient account of papyrus manufacture is Pliny Natural History 13.74–89. Papyrus was as a rule imported to Italy, but it is possible that the highest- quality pens also were: e.g. Martial’s gifted pens are Memphitica (Epigrams 14.38).

5. Quint. Inst. 10.3.31.

6. Persius Satires 3.19.

7. Horace Satires 2.3.7.

8. Plin. NH 13.80. The quality of papyrus paper had apparently improved significantly between the Augustan period and Pliny’s day.

9. Plin. NH 13.89.

10. Cic. Letters to Atticus 2.13.

11. White (2010), 67, with 199 n. 24. Cf. Cic. Att. 2.19.5.

Figure 1 Ptolemaic pen set bound to a palette with linen. Brooklyn Museum 37.451E. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

height of his fame the novelist Apuleius brags that he would trade all the goods in the world for a writing pen, most Roman authors are not nearly so bullish.12

Despite frustrations, Romans did write, and wrote a lot. If the deposits of ancient wooden leaf tablets found at military settlements across Roman Britain are any sign, Roman citizens with even moderate education put pen to paper (or, in this case, to thin slip of wood) for lots of reasons: to ask for more beer and socks; to ask one’s superior for leave; to copy lines from the Aeneid as schoolwork; and, in an example famously signed in the hand of a Roman woman, Claudia Severa, to invite a friend to one’s birthday party.13 The remains of documents from Roman Egypt, where papyrus was the writing surface of choice, tell a similar story: writing used to secure funds or issue IOUs, writing used to introduce friends or to warn acquaintances of conmen and cheats (as in Suneros’s note to Chios, POxy 3208, reproduced in Chapter 1), writing of letters sent home to parents, writing of parents to children, writing of school children and their teachers, and copyists making books.14 Much of this material was written by scribes, professionals, paid to take down dictation or to write up standard documents such as receipts and contracts, who could be slaves, freedmen, or citizens.15 But many people who hired scribes signed their own names, and it is clear that the business of being Roman by the turn of the

12. Apuleius Florida 9.27: pro his praeoptare me fateor uno chartario calamo me reficere poemata, “above these, I confess I choose a single writing pen to create poetry.”

13. See Bowman and Thomas (1983) and (2003); Bowman (1994); and Bowman et al. (2010). Tomlin (1996) is still a useful review of the material. Severa’s letter is Tab. Vindol. II 291.

14. For an introduction to the variety of material, see the essays collected in Bagnall (2009), with further bibliography pp. 27–9.

15. See the discussion of Palme in Bagnall (2009), 358–94. When he was busy, Cicero himself often had a scribe (librarius) write his letters, e.g., Q Fr. 2.16: occupationum

millennium involved frequent recourse to written documents in daily life.16 High and low, male and female, young and old: the discoveries from Roman Britain and Egypt, and even the scarce examples of papyrus and tablet documents and wall inscriptions that survive in Italy itself, reveal traces of the whole breadth of the Roman people.17

Yet the surest sign that Romans wrote and read may indeed be the rich legacy of literary texts that have reached us not through their direct physical survival, but through a long and complex history of copying and recopying in the age of manuscript books. Beginning at least in the third century bce, with the staging of theatrical ludi, Rome became a center for the production of literary works.18 Some of them, including the ludi Romani themselves, were translations and adaptations of Greek models, from the epics of Homer translated by Livius Andronicus and freely romanized by Virgil to philosophical writings of Epicureans, Academicians, and Stoics.19 Others took originally Greek forms in radical new directions, such as profound innovations in the genres of love elegy, hexameter satire, and literary epistle. According to L. D. Reynolds and Nigel Wilson, by the year 500 ce, in the Latin west, Plautus, Terence, Virgil, Ovid, Lucan, Persius, Juvenal, Cicero, Sallust, Livy, both Plinys, Seneca, and Fronto were actively circulating in manuscript: works of drama, prose, and poetry by authors who had been dead for three centuries or more.20 In the ensuing millennium, many, if not most, classical texts continued to be maintained and renewed through copying within a network of monastery scriptoria and cathedral libraries across Europe.21 The rise of the printing press in the sixteenth century again provided a new vehicle for classical learning, a machine fueling the study of Greek and Latin authors even into our own age, when we find ourselves once more in the throes of a media revolution that is reshaping our contact with classical learning.22

mearum tibi signum sit librari manus, “Let the hand of my scribe be to you a sign of my busyness.”

16. Bagnall (2011). Harris (1989), of the late Republic and the high Empire: “In manifold ways [. . .] the Roman world was now dependent on writing” (p. 232).

17. Graffiti: Garrucci (1856); Canali and Cavallo (1991); Solin et al. (1966); Milnor (2014) discusses literary connections. Italian papyri and other documents: Capasso (1991).

18. On the importance of the ludi for Rome’s sense of literature, see Wiseman (2015). If I can be accused of overestimating the importance of writing in the Roman world, Wiseman may be accused of underestimating it.

19. See especially Feeney (2016) on Rome’s “translation project.”

20. Reynolds and Wilson (2013, orig. 1968), 81.

21. Reynolds and Wilson (2013, orig. 1968), 80–122.

22. Kallendorf (2015) is a fascinating study of the reception history of Virgil across time and media, up to today. See also Pfeiffer (1976); Grafton (1997); O’Donnell (1998); Grafton et al. (2010); and now Hunt, Smith, and Stok (2017).

Interest in the history of the book in Europe has refocused attention on the ways that texts are continually reconstituted in the hands of makers and readers.23 At the same time, classical scholarship has done enormous work to recuperate the original performativity of ancient texts.24 But just as the ideals of song, performance, and occasion have considerable symbolic weight within ancient literatures, so too did writing, and its various forms play a significant symbolic role in the work of authors and artists across genres. Other languages do a better job than English to distinguish writing itself (i.e., marks, made on a surface, having some kind of linguistic character) from the acts that produce it (i.e., the making of such marks) and its metaphysical products (i.e., the linguistic information encoded therein). French has écriture, écrire, and écrits; German, Schrift and schreiben. In English, all of these are “writing.” By “writing,” then, I mean those marks, stains, scratches, impressions, scores, gashes, grooves, and lines that are the visible signs of verbal communication, as well as the material substrates or physical media that were made to contain them.25

Bugs can be features, too. Rather, like Cicero’s letter to Quintus, writing’s very failures always to transmit the perfect intention of an author—and the failures of certain pieces of writing ever to reach their intended readers—reveal one of writing’s most productive potentialities: that the medium is not actually the message. That is, the inscribed artifact (the object that bears writing) and the literary work (the intellectual substance embedded in it) are not one and the same. This difference allows authors to play with the concinnity between form and content in ways that are legible and meaningful to readers. Ovid dresses his book poorly, since the poetry it contains is full of sorrow. Catullus jokes about the grandness of a papyrus sheet used to copy the most overblown poetry. Horace’s booklet of Odes can claim to outlast a monument. For Virgil, we shall see, the particular textuality of his poetry becomes a kind of secret confidence between the author and a coterie of readers, including the princeps and excluding the general reading public.26

One of the greatest challenges of working in this field is the very poor state of the material evidence for ancient Latin books. Hardly a lick of Latin literature survives in its original form from the first centuries bce or ce. I can

23. See Cavallo and Chartier (1999, orig. 1995). Darnton (1986) is seminal.

24. The foundational work is Lord (1960). For Roman song and performance, see Habinek (2005); Lowrie (2009).

25. On the semiotic implications of the characteristic of writing (and all other forms of communication) that it can be used to refer to itself, see Winthrop-Young (2013) with Siegert (2014), 10–12.

26. Ovid Tristia I.1; Catullus 22; Hor. Carmina 3.30; Virgil passim. These examples are discussed in more detail elsewhere: Ovid, in Chapter 6, and the rest in Chapter 5. Bibliographic references can be found there.

count the scraps of professionally produced poetry books on the fingers of one hand: fifty-two lines of a poem about the Battle of Actium from the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum; twenty-five lines of a comedy from the time of Quintilian, now in Hamburg; twenty on parchment of a poem about Philip of Macedon from Oxyrhynchus; another nine of the elegist Cornelius Gallus from Upper Nubia.27 A bit more prose has survived— a fragmentary copy of Cicero’s Verrines, scraps of otherwise unknown culinary and grammatical treatises, bits of a speech by Claudius and of a juridical handbook—but not a lot.28 If the silence of the material record is almost deafening, that of Roman authors about the human labor that flowed behind the books they wrote is almost equally so: slaves made to copy dictation, secretaries asked to make corrections, copyists making clean drafts in bookshops. They leave barely any trace in the literary texts of our authors, though it is clear that their handiwork runs through Roman literature like a torrent.29

In the face of such remarkable absences, how are we to tell the story of the Latin book in antiquity? We must take guidance from other forms of writing that survive in larger numbers: epigraphic inscriptions on stone and bronze from Italy and the empire; graffiti preserved on the plaster walls of the cities destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius; fragments of Greek books and other papyrus documents in Greek and Latin that have endured by the thousands in the waste piles of Roman Egypt; precious traces of Latin writing on wooden tablets from Britain, Egypt, and the Vesuvian cities; and the depictions of scrolls and other media in the iconography of Roman wall paintings and statuary.30 This book therefore asks us to imagine how the lives of all of those dwelling in Rome were meaningfully embedded within a particular, evolving media landscape: in the shadow of laws posted in bronze on the Capitoline and the tituli displayed on new public monuments, including Augustus’s libraries on the Palatine and at the Porticus of Octavia; among the bookstalls of the Vicus Tuscus and the graffiti of the forum; coming and going past the mile markers and suburban epitaphs that lined the Via Appia and the other roads that led to Rome; fingering coins with alphabetic legends and, often, keeping or commissioning their own records and account books. Despite the low levels of literacy continuing into the Augustan age— one scholar guesses no more than 20 to 30% of the adult male population would have read to the current UNESCO standard—the symbolic and expressive qualities

27. The survivors are catalogued by Ammirati (2015), 23–44. See also Cavenaile (1981).

28. Ammirati (2015).

29. Cicero’s letters are the exception. On literary labor generally, see Cavallo et al. (1989–2012), vol. 1, Produzione del testo; Puglia (1997).

30. For the representations of bookrolls in Roman art, see still Birt (1907). Other topics listed here are treated more fully in the current study.

of writing, beyond their linguistic content, must have been much more widely legible.31 Moreover, in the context of Rome’s growing dominion in Italy and abroad, authors, too, seem to have been increasingly aware that they communicated not only with immediate audiences at the capital, but also educated readers throughout the Latin-speaking world who accessed their works only through the written word: Zmyrna cavas Satrachi penitus mittetur ad undas, “[Cinna’s] Smyrna will travel as far away as the deep- channeled streams of Satrachus” (Catullus 95.5, tr. Goold). Rome’s was the first republic; so too, the first “Republic of Letters.”

As we shall see in Chapter 2, the florescence of the Latin alphabet at Rome is situated uniquely between the development of earlier linear alphabets in the eastern Mediterranean in the first half of the first millennium bce and the rise of the codex book-form in the first centuries of the first millennium ce The earliest writing in Italy appears in Latium in the first half of the eighth century bce, around the same time that we see significant signs of Roman urbanization: the settlement of the Palatine Hill, the building of the first stone structures in the forum, the beginnings of changes to the city’s topography.32 These developments coincide with the traditional date of Romulus’s foundation of the city in 753 bce. Potsherds from the Roman Forum show the appearance of writing in the city not very much later.33 Unlike the Greeks and Etruscans, to whom Romans continued to compare themselves, the Roman state was thus the first major power in the ancient Mediterranean to come into being in the context of alphabetic literacy. That is, there was essentially never a time in the history of the city when writing was not in some way present. Even if only a small percentage of the population was able to read and write at any point in time, in a fundamental sense, Rome has always been a literate city.34 Since at least 1948, when Ernst Curtius posited the trope of books and writing as one of the foundational images in the classical tradition, scholars of literature have been probing self-reflexive uses of the figure of writing within writing.35 But Curtius himself downplayed the writing’s figurative importance during the very era with which we are concerned here: “Roman literature in its period of florescence made very little use of book metaphors [. . .] It is barely

31. This is a question to which we shall return again and again in this study. Perhaps the foundational discussion of the “expressiveness” of textual media is McKenzie (1986).

32. Cornell (1995); Holloway (1994). On the earliest writing in Latium, the so- called Eulin inscription, see Watkins (1995) and Bietti Sestieri (1989–90) and now Janko (2015), who puts the date even earlier.

33. Colonna (1988).

34. I mean “literate” in the broadest sense here. Cf. Rama (1996, orig. 1984). Harris (1989) estimates actual rates of literacy in ancient cities over time.

35. Curtius (1953), 302–47.

represented in the stock of images of Augustan poetry.”36 Similarly, in his seminal work on the history of writing systems, I. J. Gelb insisted that the Roman writing habit was derivative and unexceptional:

One would look in vain [. . .] in this study for a discussion of Latin writing through ancient, medieval, and modern times, because that system represents nothing new and important for the theory of writing. Generally speaking, we write to- day the way the ancient Romans did, and the ancient Latin writing is identical in principle with that of the Greeks, from whom it was borrowed.37

Because the Romans and Greeks shared so very much, from their myths to their meters, it can often seem as though differences between them are too subtle to be meaningful. And, indeed, we find many more points of correspondence than distinction between Greek and Roman practice throughout this study. But focusing on Roman literature and Latin authors draws both similarities and differences into relief.

A simple example from epigraphy may be illustrative. In general, in Greece, posted laws were inscribed in stone, either on the walls of public buildings or on freestanding stelae.38 In classical Italy, on the other hand, laws were typically inscribed on bronze tablets.39 Both materials are extremely durable if not directly tampered with—Greek and Roman laws, in significant numbers, survive in their original form to this day—and thus connote permanence, naturally a desirable characteristic for documents that were themselves meant to be long lasting.40 But why the preference for stone in one case and bronze in the other? It is not because Romans had greater access to bronze, or Greeks to stone. Quite the opposite; Italy was relatively poor in natural deposits of metal.41 Rather, in either case it has been suggested that, despite exceptions, the material chosen was the one that had traditionally been associated with religious inscriptions, above and beyond its legal use. Since laws across the ancient world were enacted with expectation of divine sanction, the preferred material in each place was that which was seen to have the greatest

36. Curtius (1953), 308–9.

37. Gelb (1963), v–vi.

38. Thomas (1995). Thomas (1992), 87 also ties the use of stone as a substrate for civic inscriptions to the mnemonic and monumental uses of natural rocks in archaic Greece.

39. Williamson (1987).

40. For a précis or surviving epigraphic evidence, with further references, see the entry by Kaja Harter-Uibopuu in EAH s.vv. Law, epigraphical sources for (Greek and Roman).

41. See BNP s.v. Mining.

efficacy for establishing a law’s sacred protection.42 In this case and in others, understanding a difference in attitudes toward textual materiality allows us to recognize a continuity between Greek and Roman practice that is otherwise hidden.

The project of this book is to keep both kinds of evidence in mind while we are reading ancient writers: the literary and material. In that regard, it joins a growing body of research on reading and writing in the ancient Mediterranean. For Greece and Rome, Ancient Literacy was a turning point.43 Despite its limitations, this is a text to which every subsequent study of reading and writing in ancient Greece and Rome has been indebted.44 Equally influential is the work of Rosalind Thomas, who extends an interest in questions of readership to consider the cultural factors that contributed to the development of literate practices in ancient Greece.45 Studies on the social character of writing materials at Rome, such as those of Elizabeth Meyer and Shane Butler on the uses and abuses of legal documents, draw on the insights of Thomas and others.46 In other languages, Guglielmo Cavallo and Horst Blanck, inter alios, have made significant contributions to placing the history of writing in antiquity into the larger field of histories of the book.47 Meanwhile, new work on the papyrological remains of antiquity continues to flow out of Italy, the United Kingdom, the University of Michigan, and elsewhere, providing essential knowledge for Roman book culture and writing on which I have drawn extensively.48 I am also deeply indebted to previous scholarship on Roman authors, collective and individual.49 If this study distinguishes itself in any way from what has come before, it is in drawing attention to (1) the Roman alphabet, (2) the

42. In this connection, Bodel (2001), 23 mentions other examples of “extra-textual, metaphorical elements” in the choice of epigraphic materials, including the use of lead for curses (“its density and pallor conveyed negative associations appropriately directed at the target”) and of gold for Orphic prayers (“because the words they carried were valuable and the world to which they promised access was golden”).

43. Harris (1989).

44. Specific responses to Harris are Humphrey (1991); Bowman and Woolf (1994); Johnson and Parker (2009).

45. Especially Thomas (1989) and (1992).

46. Meyer (2004) and Butler (2002).

47. E.g., Cavallo and Chartier (1999, orig. 1995) and Blanck (1992). Birt (1882) was foundational.

48. Highlights include Tomlin (2016) on the London tablets; Ammirati (2015) on Latin books; Obbink (2007) on the Latin texts of Herculaneum. Johnson (2004) remains essential on the bookrolls of Oxyrhynchus, and Bagnall’s (2011) work on “everyday writing” has had special impact on this study.

49. Of particular influence are Feeney (2016); Lowrie (2009); and Goldberg (2005), as well as Oliensis (1998) on Horace and Martelli (2013) on Ovid.

material culture of Roman literate practice, and (3) the impact of writing media on broader intellectual, epistemological, artistic, and social constructions. This approach is anticipated by the studies collected in the 2009 Ancient Literacies volume, but it has never been the focus of a book-length study and never one on Roman writing, rather than Greek.50

The book takes as its starting point the history of Roman alphabetism and alphabetic literacy, but throughout I look past mere letters. My concern is with identifying and analyzing how authors of the late Republic and early Empire thought about and through textual materiality, especially in light of existing material evidence for ancient writing. The reader should know that I am neither an epigrapher nor a papyrologist, though I have tried as much as possible to represent the technical material from those fields accurately and have relied on the expertise of generous friends and colleagues throughout. This book is deeply indebted to previous scholarship in all of the fields that it touches. Its readings are meant not to be determinative on their own. Rather, I have sought to cast a light on those aspects of Roman thought and literature that appear to me to have become most obscure because of the dissimilarity between the ways we experience texts in the modern age and the ways the ancient Romans experienced them. In what may be one of the most rudimentary applications of the poststructuralist principle, by defamiliarizing the text itself, we come to see it anew.

The chapters that follow are loosely organized into three sections of two chapters each. Chapters 1 (“Classics and the Study of the Book”) and 2 (“Writing and Identity”) address preliminary questions of scholarly and historical background, in the first case finding common ground among the related disciplines of book history, bibliography, textual criticism, and the Classics, so that scholars of each of those fields may approach this book on equal footing. In the second, I look at the broadest possible historical sources, from Herodotus to Tacitus, to understand what stories ancient Romans told themselves about the origins of their alphabet and how they used those myths and histories to connect themselves with other, more ancient writing cultures in and around the Mediterranean basin, including the Greeks. Chapters 3 (“The Text of the World”) and 4 (“Tablets of Memory”) focus on the use of writing in two governing metaphors in Roman didactic literature: the famous analogy between letters and atoms in the natural philosophy of Lucretius’s De rerum natura and the image of the “wax tablet of the mind” in classical theories of memory and rhetoric. Borrowing Aleida Assmann’s notion of the “figure of thought,” we see in either case how writing, or a particular feature of it, became embedded into the very ways that the ideas of matter and the mind were formulated within their respective intellectual traditions. Chapters 5 (“The Roman Poetry Book”) and 6 (“Ovid and the Inscriptions”) round out the study by focusing on Roman

50. Johnson and Parker (2009).

poetry: first, on representations of bookrolls and authorial writing within the poetic tradition in Latin in the longue durée, including Virgil’s peculiar avoidance thereof, and, next, on the iconic use of books and inscriptions in a series of poems from Ovid’s collections of exile poetry, the Tristia. In both cases, though to very different ends, we find that representing different kinds of textual media within their poetry allowed Roman authors to signal and negotiate their relationships with readers in the world outside of their poems, including that most important reader of all, Augustus. The Conclusion offers some further thoughts on the intrinsic nature of texts as objects, using an ancient papyrus miscellany from Roman Egypt—the earliest surviving manuscript example of indented, elegiac mise en page to discuss, again, the importance of the symbolic functions of writing in our reading of Roman evidence.

My hope is that students of other periods of antiquity and of other kinds of books and literature will find much of interest here. When quoting ancient sources, I provide both the original text in Latin or Greek, as well as a translation in almost every case, to satisfy the needs of classicist and non- classicist readers alike. The problems I discuss center on some of the most canonical voices in Roman letters, including Lucretius, Cicero, Virgil, Horace, and Ovid. Cicero, the oldest of my key authors, was killed in the midst of this political upheaval, at the height of his career in 43 bce, the same year that the youngest of my authors, Ovid, was born. The fact that these men happen to have lived and worked within a century of one another is hardly an accident. Rather, it reflects the wealth, both cultural and economic, of Rome at that moment, at the turn of the millennium, having fully unified Italy, and endeavoring to control an even broader and more prosperous empire across the Mediterranean and Europe. This period effectively marks the end of Rome’s wars at home. Caesar had been killed the year before; Anthony and Octavian were to finish their civil war abroad at the end of the next decade. And it marks the beginning of a great age of expansion and enfranchisement of colonies in northern Africa, northern Europe, Iberia, and the Mediterranean East. The present study loosely spans the seventy-seven-year lifetime of the man who was to be Augustus: born Gaius Octavius in 63 bce, renamed Caesar Octavian at the time of his posthumous adoption by Julius Caesar in 44 bce, remade again with the honorific Augustus by the senate of Rome in 27 bce, and deified by them upon his own death in 14 ce. While this book is not about the relationship between Augustus and the poets, it does address the effects of the changing political order in this period on literary representations of writing.51 Although there was no major technological innovation at this time, one can think of empire itself as a significant part of the media history of antiquity. Empire caused words and

51. For Augustus’s relationships with poets, the bibliography is vast. Miller (2009); Barchiesi (1997, orig. 1994); and Farrell and Nelis (2013) are all good points of entry.