CONTENTS

Foreword by Adam Neely • xv

Preface: The Music Class at the End of the World • xvii

Acknowledgments • xxi

To the Reader • xxv

To Public School Teachers • xxv

To Independent Music Teachers • xxv

To Everyone • xxvi

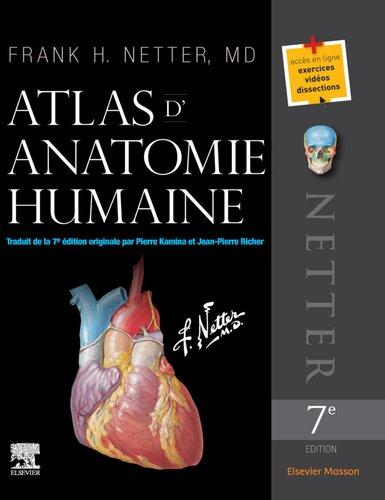

PART I WHAT YOU NEED TO START YOUR OWN ELECTRONIC MUSIC

SCHOOL • 1

1 Toward a Creative Music Curriculum • 3

1.1. The Creative Music Teacher • 3

1.2. Addressing Students Who Typically Don’t Take Music Classes (The Other Eighty Percent) • 5

1.3. How Music Technology Can Fit into a Broader Performing Arts Curriculum • 7

1.4. The Divide Between Music Teachers’ Definition of Music and Students’ Definition of Music • 8

2 An Art Class for Music • 12

2.1. Portfolio Creation • 12

2.2. Computer as Tool Versus Computer as Medium • 13

2.3. Songwriting and Sound Creation • 14

2.4. Remixing • 15

2.5. Sampling • 15

3 Understanding What a School Really Wants • 19

3.1. Who Makes Decisions About Curriculum? • 19

3.1.1. The Teacher • 19

3.1.2. Administrators • 19

3.2. Selling the Lab-Based Music Course • 20

3.2.1. Administrators and School Leaders • 20

3.2.2. Teachers • 21

3.2.3. Parents • 21

3.2.4. Students • 21

3.3. How Music Tech Benefits the Master Schedule • 22

3.4. How Music Tech Benefits the Music Department’s Profile • 22

3.5. Sweetening the Deal with Graduation Requirements • 23

3.6. Getting Funding and Staying Funded • 23

3.7. Protecting Your Investment • 24

3.8. Criticisms of a Nontraditional Music Class • 25

4 Tech You Will Need for Your Program • 27

4.1. The Computer • 27

4.2. Headphones • 28

4.3. MIDI Input Devices • 28

4.4. Getting a Space • 31

4.5. Possible Room Configurations • 32

4.6. Choosing Other Hardware for the Lab • 33

4.7. Setting Up an Individual Station • 34

4.8. Building on Existing Infrastructure • 34

4.9. Day- to-Day Considerations • 36

4.10. Maintenance and Cleaning • 37

5 Ableton Live and Push • 40

5.1. An Optimal Setup • 40

5.2. Why These Tools? • 41

5.3. Ableton Live Basics: Arrangement View and Session View • 41

5.4. Ableton Push Overview • 42

5.4.1. Do You Really Need One? • 43

5.4.2. Techniques Afforded by Push • 43

5.4.3. Drum Programming • 44

5.4.4. Chords and Melodies • 44

5.5. Comparisons to Other DAWs • 44

PART II CREATIVE ELECTRONIC MUSIC PROJECTS FOR THE MASSES • 47

6 Designing Creative Music Projects • 49

6.1. Working with Beginners • 49

6.2. Philosophy • 50

6.3. Process Versus Product • 51

6.4. Customization and Aesthetic Opportunities • 53

6.5. Pacing • 53

6.6. Listening to and Observing Students • 54

6.6.1. Techniques for Pop- Cultural Ethnographic Observation • 54

6.6.2. Tips for Incorporating a New Trend in Your Teaching • 55

6.7. The Project Formula • 56

6.8. Technical and Aesthetic Goals • 57

6.9. Deconstructing a Genre • 59

6.10. Universal Techniques • 59

6.10.1. Provide Default Tracks and Presets • 59

6.10.2. Add Variety Through MIDI Manipulation • 59

6.10.3. Scenes as Form • 59

6.10.4. Recording to Arrangement View • 60

6.10.5. Eight-bar Phrases • 60

6.10.6. Song Structure • 60

6.10.7. Fuzzy Boundaries and Fill Bars • 60

6.10.8. Making Songs End Gracefully • 60

6.11. The Prime Directive • 60

7 Teaching Recording and Sampling with Audio Projects • 62

7.1. Designing Projects Centered on Audio • 62

7.1.1. Play, Stop, Record • 62

7.1.2. The Timeline • 62

7.1.3. Recorded Audio • 63

7.1.4. Basic Editing Skills • 64

7.1.5. Loops • 66

7.1.6. Ableton Live’s Session View • 67

7.1.7. Ableton Live’s Arrangement View • 67

7.2. Project Example: Arranging Clips • 69

7.2.1. Project Duration • 69

7.2.2. Technical Goals • 69

7.2.3. Creative Goals • 69

7.2.4. Listening Examples • 69

7.2.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 69

7.2.6. Project Design • 70

7.2.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 70

7.2.8. Troubleshooting • 73

7.2.9. Differentiated Instruction • 73

7.2.10. During Work Time • 74

7.2.11. Assessment Strategies • 74

7.3. Project Example: Unreliable Product Ad • 74

7.3.1. Project Duration • 74

7.3.2. Technical Goals • 75

7.3.3. Creative Goals • 75

7.3.4. Listening Examples • 75

7.3.5. Materials Needed • 75

7.3.6. Before Teaching This Lesson • 75

7.3.7. Project Design • 75

7.3.8. Day-by-Day Plan • 76

7.3.9. One-Hour Version • 78

7.3.10. Troubleshooting • 78

7.3.11. Differentiated Instruction • 79

7.3.12. During Work Time • 80

7.3.13. Assessment Strategies • 80

7.3.14. The Comedy Pyramid • 80

7.4. Project Example: Simple Remix • 82

7.4.1. Project Duration • 82

7.4.2. Technical Goals • 82

7.4.3. Creative Goals • 82

7.4.4. Listening Examples • 82

7.4.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 82

7.4.6. Project Design • 84

7.4.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 86

7.4.8. Troubleshooting • 88

7.4.9. Differentiated Instruction • 89

7.4.10. During Work Time • 89

7.4.11. Assessment Strategies • 89

7.4.12. Making This Project Your Own • 89

7.5. Project Example: Picking Apart a Multitrack • 90

7.5.1. Project Duration • 90

7.5.2. Technical Goals • 90

7.5.3. Creative Goals • 90

7.5.4. Listening Examples • 90

7.5.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 91

7.5.6. Project Design • 92

7.5.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 93

7.5.8. Troubleshooting • 94

7.5.9. Differentiated Instruction • 94

7.5.10. During Work Time • 95

7.5.11. Assessment Strategies • 95

7.5.12. Making This Project Your Own • 95

7.6. Project Example: Custom Cover Song • 96

7.6.1. Project Duration • 96

7.6.2. Technical Goals • 96

7.6.3. Creative Goals • 96

7.6.4. Listening Examples • 96

7.6.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 96

7.6.6. Overview of the Technique • 97

7.6.7. Syncing the Guide Track Using Ableton Live • 98

7.6.8. Cultural Considerations • 100

7.7. Project Example: Movie Soundtrack • 101

7.7.1. Project Duration • 101

7.7.2. Technical Goals • 101

7.7.3. Creative Goals • 101

7.7.4. Examples • 102

7.7.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 102

7.7.6. Project Design • 103

7.7.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 103

7.7.8. Troubleshooting • 107

7.7.9. Differentiated Instruction • 109

7.7.10. During Work Time • 110

7.7.11. Assessment Strategies • 110

7.7.12. Making This Project Your Own • 111

8 Teaching Songwriting with MIDI Projects • 112

8.1. Software Instruments Versus MIDI • 112

8.1.1. Drums Versus Not-Drums, Step Time Versus Real Time • 113

8.2. Functional Music Theory • 114

8.3. Elements of Music • 115

8.4. Sound Design • 116

8.5. Genre Deconstruction • 117

8.6. Project Example: Drum Programming • 117

8.6.1. Project Duration • 117

8.6.2. Technical Goals • 117

8.6.3. Creative Goals • 117

8.6.4. Listening Examples • 118

8.6.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 118

8.6.6. Project Design • 118

8.6.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 118

8.6.8. Troubleshooting • 125

8.6.9. Differentiated Instruction • 125

8.6.10. During Work Time • 126

8.6.11. Assessment Strategies • 126

8.7. Project Example: Beatmaking • 127

8.7.1. Project Duration • 127

8.7.2. Technical Goals • 127

8.7.3. Creative Goals • 127

8.7.4. Listening Examples • 127

8.7.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 127

8.7.6. Project Design • 128

8.7.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 129

8.7.8. Troubleshooting • 132

8.7.9. Differentiated Instruction • 133

8.7.10. During Work Time • 133

8.7.11. Assessment Strategies • 133

8.8. Project Example: Slow Jam • 134

8.8.1. Project Duration • 134

8.8.2. Technical Goals • 134

8.8.3. Creative Goals • 134

8.8.4. Listening Examples • 134

8.8.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 134

8.8.6. Project Design • 135

8.8.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 136

8.8.8. Troubleshooting • 145

8.8.9. Differentiated Instruction • 146

8.8.10. During Work Time • 146

8.8.11. Assessment Strategies • 146

8.9. Project Example: Future Bass • 147

8.9.1. Project Duration • 147

8.9.2. Technical Goals • 147

8.9.3. Creative Goals • 147

8.9.4. Listening Examples • 147

8.9.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 148

8.9.6. Project Design • 148

8.9.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 149

8.9.8. Troubleshooting • 156

8.9.9. Differentiated Instruction • 157

8.9.10. During Work Time • 157

8.9.11. Assessment Strategies • 157

8.10. Project Example: House Music • 158

8.10.1. Project Duration • 158

8.10.2. Technical Goals • 158

8.10.3. Creative Goals • 158

8.10.4. Listening Examples • 158

8.10.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 158

8.10.6. Project Design • 158

8.10.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 159

8.10.8. Troubleshooting • 164

8.10.9. Differentiated Instruction • 165

8.10.10. During Work Time • 166

8.10.11. Assessment Strategies • 166

8.11. Project Example: Trap Beats • 166

8.11.1. Project Duration • 166

8.11.2. Technical Goals • 166

8.11.3. Creative Goals • 167

8.11.4. Listening Examples • 167

8.11.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 167

8.11.6. Project Design • 168

8.11.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 168

8.11.8. Troubleshooting • 171

8.11.9. Differentiated Instruction • 173

8.11.10. During Work Time • 173

8.11.11. Assessment Strategies • 173

9 Teaching Creativity with Outside-the-Box Projects • 175

9.1. Designing Projects to Teach Originality • 175

9.2. Irreverence • 176

9.3. Repurposing Ideas That Exist Already • 177

9.4. Finding Your Voice • 177

9.5. Project Example: Soundscape • 178

9.5.1. Project Duration • 178

9.5.2. Technical Goals • 178

9.5.3. Creative Goals • 178

9.5.4. Listening Examples • 179

9.5.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 179

9.5.6. Project Design • 179

9.5.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 179

9.5.8. Troubleshooting • 184

9.5.9. Differentiated Instruction • 184

9.5.10. During Work Time • 185

9.5.11. Assessment Strategies • 185

9.6. Project Example: Vaporwave and Lo-Fi Hip-Hop • 186

9.6.1. Project Duration • 186

9.6.2. Technical Goals • 186

9.6.3. Creative Goals • 186

9.6.4. Listening Examples • 186

9.6.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 186

9.6.6. Project Design • 187

9.6.7. Day-by-Day Plan • 187

9.6.8. Troubleshooting • 193

9.6.9. Differentiated Instruction • 193

9.6.10. During Work Time • 193

9.6.11. Assessment Strategies • 194

9.7. Project Example: Video Beatboxing • 194

9.7.1. Project Duration • 194

9.7.2. Technical Goals • 194

9.7.3. Creative Goals • 195

9.7.4. Video Examples • 195

9.7.5. Audio Examples of Found Sounds in the Drum Parts • 195

9.7.6. Before Teaching This Lesson • 195

9.7.7. Project Design • 195

9.7.8. Day-by-Day Plan • 196

9.7.9. Troubleshooting • 199

9.7.10. Differentiated Instruction • 200

9.7.11. During Work Time • 200

9.7.12. Assessment Strategies • 200

9.8. Project Example: Sampling • 201

9.8.1. Project Duration • 201

9.8.2. Technical Goals • 201

9.8.3. Creative Goals • 201

9.8.4. Listening Examples • 201

9.8.5. Before Teaching This Lesson • 202

9.8.6. A Crash Course in Musical Intellectual Property • 202

9.8.7. Project Design • 203

9.8.8. Day-by-Day Plan • 203

9.8.9. Troubleshooting • 208

9.8.10. Differentiated Instruction • 209

9.8.11. During Work Time • 210

9.8.12. Assessment Strategies • 210

9.9. The Final Project • 211

9.9.1. Project Duration • 211

9.9.2. Goals • 211

9.9.3. Project Design • 211

9.9.4. Day-by-Day Plan • 212

9.9.5. Troubleshooting • 214

9.9.6. During Work Time • 215

9.9.7. Assessment Strategies • 215

10 Common Issues in Music Lab Lessons • 217

10.1. Weak Student Engagement • 217

10.2. Projects Take Too Long • 217

10.2.1. Strategy One: Real Artists Ship • 218

10.2.2. Strategy Two: More One-on-One Help • 218

10.2.3. Strategy Three: Pencils Down • 218

10.3. Projects End Too Quickly • 218

10.4. Students Are Afraid to Show Their Projects • 219

10.5. I Can’t Think of Ideas for Projects • 220

10.6. Staying Relevant • 220

10.7. I Went to School for Music. How (or Why) Should I Manage a Computer Class? • 221

10.8. Students Are Trying Hard, But They Always Seem Lost • 222

11 Assessing Music Lab Projects • 223

11.1. Intrinsic Motivation • 223

11.2. Critical Listening • 224

11.3. Practical Considerations • 224

12 Future-proofing the Electronic Music School • 226

12.1. Refreshing Old Projects • 226

12.1.1. Strategy 1: Update the Elements of a Project That Involves Choices • 227

12.1.2. Strategy 2: Acknowledge Defeat and Make Fun of Your Past Self • 227

12.2. Outlasting a Graduating Class • 227

12.3. Maintaining Skills Between Old and New Projects • 228

12.4. Adapting to New Teaching Formats • 229

12.5. Committing to a Platform (or Not) • 230

PART III COMMUNITY MUSIC CULTURE AND EXTRACURRICULARS

• 233

13 Live Performing and Afterschool Groups • 235

13.1. Preparing Students for a Musical Life Outside of School • 235

13.2. Model One: Recording Club • 235

13.3. Model Two: The House Band • 236

13.4. Model Three: Electronic Music Group • 237

13.4.1. The Birth of the Electronic Music Group • 237

13.4.2. Equipment • 238

13.4.3. A Student Perspective on EMG • 244

13.4.4. The Live Set • 245

14 Understanding Student-Led Groups • 247

14.1. The Teacher’s Role (Hint: Very Different) • 247

14.2. Remember the Prime Directive • 248

14.3. Building Creative Teams • 248

14.4. The Whiteboard Session • 249

14.5. Giving and Taking Criticism • 251

14.6. Refining Ideas Before They Get Made • 253

14.7. Facilitating, or “What Can You Do That They Can’t?” • 253

14.8. How Ideas from Student-Led Groups Benefit Lab-Based Courses • 256

14.9. The Core Values • 256

14.10. Going Beyond Music: Film, TV Shows, Other Content, and Media Production • 256

15 Virtual Electronic Music School • 260

15.1. Burn It All Down • 260

15.2. Change Everything • 260

15.3. Moving the Electronic Music School Online • 261

15.3.1. Smaller Group or Individual Meetings • 262

15.3.2. Synchronous Class Meeting That Breaks into Smaller Groups • 262

15.3.3. Asynchronous Online Class • 262

15.3.4. Live- Streaming Sessions • 263

15.4. Rebuilding • 264

16 A Rising Tide • 265

16.1. Maximum Reach and Demographics • 265

16.2. How Traditional Music Groups Thrive Because of Project-Based Courses • 266

16.3. A Performing Arts Program That Truly Elevates Culture • 267

16.4. Critical Popular Music Studies • 267

16.5. Producing and Consuming Audio • 268

16.6. Educational Goals and Social Impact • 269

16.7. The Racial Politics of Music Education • 269

16.8. Music Creation as Personal Development • 270

16.9. Building for Musical Lifetimes • 271

Index • 275