Exploring the Variety of Random Documents with Different Content

"I can't bear to have you say such things to me," she said impatiently when Lillie had offered her a compliment upon her nobility of character. "I'm not noble and I have treated you abominably."

"Treated me?" Lillie's eyes opened wide. "You've been perfectly lovely to me. You've been kinder than any one in the college, and I am very proud of it."

"You needn't be," returned Janet, gloomily; "I have deceived you."

"Do you mean you don't really like me?" asked Lillie, anxiously.

"Oh, I like you. I am fond of you, but I first sought you out because I knew you were likely to be unsuspecting and I had promised to do my share in finding out about that class supper that the sophs stole." Then she told the whole story.

The girl was silent for some moments after Janet had concluded her confession; then the smiles began to dimple around her mouth and finally she burst out into a laugh.

"I ought to be furious," she said, "but I'm not, for it is so funny, and after all, Janet, it is a sort of relief to discover that you are like other girls."

"Heavens!" exclaimed Janet. "Did you suppose I was a creature of finer mould? I am not near so nice as other girls. I should think that I had proved that."

"Yet, you are much nicer," Lillie decided, "for I do not know another one who would have been honest enough to tell me this when there was no reason in the world why she should except that she was too true to keep it to herself."

"Then you do forgive me for making you a cat's paw?"

"Yes, on one condition: that you will go home with me to spend the Easter holidays. I have been dying to ask you, and have been afraid, so now I have a new claim on you, I am going to make the most of it."

Janet hesitated, but saw that she was in for it and in the end, she gave a reluctant consent. She announced her intention to the amused group she found in Cordelia's room that afternoon.

"Poor, poor Janet," said Teddy with mock sympathy. "What an ordeal. Have you any idea of what you are getting into?"

"No, I haven't, but I'd go if her parents were ragpickers."

"I shall be wild to hear your report," said Lee. "Promise to keep back nothing."

"I'll promise no such thing," said Janet. "It's my affair, I'll have you to know," and she refused to mention the subject to her intimates again.

The visit was made and Janet returned from it in such good spirits that the others were consumed with curiosity.

"Did you have a good time?" asked Lee at the first opportunity.

"Fine," returned Janet.

"Are they nice people?" "Lovely."

"Did you meet any of their friends?"

"Yes."

"Did you like them? Were they nice?"

"The very best in the place."

"Oh, Janet, you are the most unsatisfactory person when you choose to be. Tell me about it." Lee was fairly put out.

"I have told you. I had a fine time. The Starrs are lovely people. Their friends are the best families in the place. What more do you want to know?"

"I want to know what you did."

"I ate and slept and drove and walked and enjoyed myself generally. In fact, I scarce ever had a more delightful holiday."

Lee looked at her with an injured expression upon her face, but seeing that she would get nothing further from so non-committal a person, she left her without another word, and Janet laughed softly to herself as she heard her departing footsteps.

CHAPTER XIX

FIELD DAY

IT was one day just at the beginning of the year's finals that Janet met Lee harrying through the corridor on her way to Phelps 7 with Mascot in her arms.

"Where in the world are you going with that cat?" she asked.

"I'm going to take him with me to exam," Lee answered.

"Lee Penrose, are you really?"

"Truly I am. He is so good-natured that he will keep perfectly still, if I hold him in my lap."

"But why such a frivolous performance at such a serious time? I thought you were worried over your biology."

"So I am. That is why I am taking this furry old dear with me. What's the use of having a mascot if you can't make use of it at critical times like this?" grumbled Lee.

"I'd like to see Professor Weatherby's face if he catches sight of him."

"Well, if you happen to be looking, you will see. You will be there, won't you?"

"Certainly I shall be there."

"I'm going to sit very far back. Come take a place by me, Janet, and keep me in countenance."

"I shall do nothing of the kind. Your sins be upon your own head. What are you going to do if Professor Weatherby brings you up standing? I should think you had been

deprived of about as many privileges as your record will stand."

"Oh, if he discovers me, there will be nothing to do but tell him the whole truth and nothing but the truth, and let him say whether I have not a perfectly legitimate right to use Mascot as a means to a good end. I don't want to fail, and if there is anything that can prevent it, whether philosophical or superstitious, I'll employ the means. Mascot represents superstition to be sure, but my own stand in believing that good is in all things makes up for my philosophical attitude."

"Tell that to Professor Weatherby and see what he says."

"I think you might give the sustaining influence of your friendly presence, Janet," said Lee, wheedlingly.

"No, I shall be of no use in the carrying out of your philosophy. Mascot is for the good of the whole class and I'll profit just as much by my position at the other end of the room as if I were to sit next you."

"That is a mean advantage to take of my sacrifice for common good. I didn't think you, Janet Ferguson, would be willing to share a benefit and avoid the risks."

"Go and get Cordelia," said Janet; "she is always ready for anything in the way of an innovation."

"You know Mascot is always good with you. You have a soporific influence upon him, a sort of Mrs. Winslow's soothing syrup effect, and that is why I particularly want you to be near at hand."

But Janet was obdurate. "I would be a pretty president," she said, "if I were to do anything that would bring reproof from the faculty at this juncture. I must maintain such dignity as I have because of what is expected of me, otherwise, Lee, I wouldn't mind, I must confess."

"Oh, all right then," said Lee. "Come, Mascot, you are beginning to wriggle. I'm afraid you are going to be obstreperous. If you happen to get one of your contrary attacks, I don't know what I am to do to keep you from prancing all over the place."

"Put him in a valise or basket or something," suggested Janet. "I'd provide some bits of food to stop his mouth if he begins to cry. I'd chain him to the handle of whatever you put him in. You can leave the lid open and he will keep quiet, I think. I've seen persons travel with cats carried in that way."

"I'll do it," declared Lee. "Your suggestion is worth something if your rashness isn't." And she walked off carrying Mascot under her arm.

Janet heard a protesting meow from the cat as the two disappeared.

A half hour later all was quiet in Phelps 7. Nothing was heard but the scratching of pens and the rattling of paper as the anxious students struggled through their task. Professor Weatherby gave notably hard examinations and even the most persistent "grind" felt shaky. Presently the silence was broken by a plaintive wail from the back of the room. Every head was instantly raised. There was not a girl present who did not recognize Mascot's voice.

Professor Weatherby looked up and frowned, then rose and slowly paced down the aisle. In the back row sat Lee,

her long skirts covering the valise in which crouched Mascot greedily devouring the bits of chicken which Lee had provided as a means of stopping any demonstrations on his part. Having comfortably lunched, the surfeited little beast would curl up and sleep comfortably in the straw "telescope" in which he had been conveyed to the room.

Professor Weatherby made his rounds, observed nothing and returned to his desk. Lee's red Cheeks and the twinkling smile of triumph which played around her mouth failed to betray her. For a moment, Janet was completely demoralized and the words on her paper danced before her eyes. Then she caught sight of Charity Shepherd in front of her, industriously plying her fountain pen and oblivious to all save the matter in hand, so Janet braced by this example, nerved herself against further interruption and went on with her work, completing it just as the hour was up.

Lee slipped out before any one else, and Janet saw her hurrying down the corridor lugging her basketful of cat.

"Lee," she called, "Lee Penrose, wait."

But Lee did not pause till she was safely outside the building. There Janet found her sitting on the lower step.

"Well," said Janet, "how did he behave?"

"Beautifully for a while," returned Lee; "then he got restless. When he began to howl, I thought my last hour had come, but I surreptitiously fed him chicken sandwiches till I thought he would burst. I never knew a cat with such a capacity, and the worst of it is, that I spent my last penny on the sandwiches and my meal ticket has run out. That's what one gets for sacrificing herself to the good of her fellow creatures. I don't doubt but that the entire class will pass a brilliant examination because of Mascot. In spite of

having to divide my attention between Mascot and my paper, I am pretty sure that I came through all right. How about you, Janet?"

"I think I did fairly well, though when I heard that heart-rending meow, I thought nothing would save me. Only the sight of Charity Shepherd applying her conscience to her daily need gave me stamina enough to go on. Since you have so nobly thrown yourself into the breach, Lee, there is one thing I can do and that is to stand between you and starvation. Come, we'll go to Burton's and have a sumptuous lunch."

"Janet," cried Lee, "you have saved my life. Help me to tote Mascot back to his lair, and I'll show you how generously I can appreciate your invitation."

"We must certainly have Mascot in evidence on Field Day," said Janet as the two girls sat eating their ice cream. "I think that will certainly be allowable."

"Of course," returned Lee. "What's the good of having a mascot, if he can't be placed on exhibition at such times."

"It will be our last chance, too," sighed Janet.

"Yes, by all means let us have him on the field. We'll go get some ribbons for him on our way home. He must be brave in the class colors."

"You might lead him at the head of the class," suggested Lee. "He shall have a splashing bow on his collar and a long ribbon by which he can be led. Won't he look fine? We will be very impressive with our mascot."

The plan was highly approved by the rest of the class, and was carried out as far as possible. On the morning of

Field Day, the seniors marched with banners waving and colors flying, Janet heading the procession with Mascot daintily stepping along and quite the envy of all the under classmen. To be sure Mascot sat down once or twice, and Janet had to coax him to make him go on. He was rather erratic, too, in his methods of procedure, but all went fairly well while he was within the bounds of his familiar haunts. Once outside he made an obstinate stand, set up a dismal howl and refused to behave with the docility expected of him. So in desperation, Janet picked him up and carried him into the gymnasium. There the limit of his endurance was reached, for just as all were seated Mascot made a wild dash for freedom. The ribbon which held him was suddenly jerked out of Janet's hand and she saw a gray streak clashing across the floor.

A cheer went up from the juniors to whose side he had fled. He was caught by Jessie Turner and held aloft in triumph. There was a buzz of: "The seniors' mascot has come to our side! Good luck for us! Three cheers for 1904!" and so on.

For a moment, the seniors and sophomores were staggered. It was so evident a desertion on the part of Mascot. "And so much depends upon the attitude of mind," said Charity Shepherd, really concerned for the success of her class.

Mascot's struggles did not allow Jessie to hold him long under control, though she kept a firm hold upon the long ribbon and it seemed for a time as if he must be fairly captured. He was not easily quieted, however, for at each approach of Jessie's or any of her classmates he turned with a fizz of "Keh-h-h!" And showed his teeth, savagely growling.

Then in spite of Jessie's efforts to hold him, he tugged at the string till she was obliged to follow him as he dashed around the gallery, frantic to escape. Jessie still retained her hold while he led her a chase up and down the gallery and finally he rushed over to the other side.

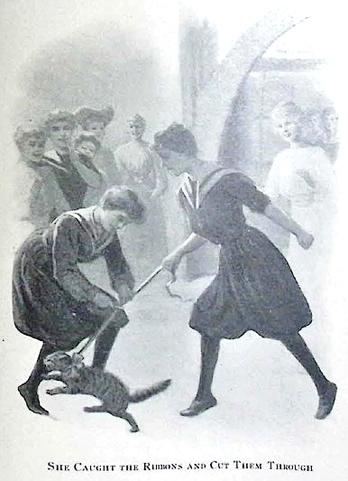

Then Janet watched her chance. Every girl was on her feet and the seniors held their breath. It would be worse than failure to allow their well-beloved Mascot to be retained as a captive, and the excitement was intense. Janet stepped out to meet the on-coming pair, the hunter and the hunted. She felt in her little chatelaine bag for a small penknife, and, as Mascot raced past, with a deft movement she caught the ribbons that held him and cut them through.

Mascot, now free, ran to the end of the gallery, leaped upon the railing and sat there. At the first symptom of an outburst from the excited students, the now thoroughly frightened creature began to look about wildly, and Janet approached him cautiously.

"Kitty, kitty, poor Mascot," she said softly stroking his bristling fur.

He looked up into her face, gave a piteous meow and allowed her to pick him up.

She gathered him into her arms and as she walked back to her place she said: "Don't cheer, please," for she saw the sophomores making ready to give their yell. She took her seat amid a soft clapping of hands, and, holding Mascot by the collar, she succeeded at last in stroking him into a serene frame of mind.

SHE CAUGHT THE RIBBONS AND CUT THEM THROUGH.

Then the players went on with their basketball. First victory for the juniors, then a steady increase in the gains of the seniors till triumphantly they retired from the field. All of Janet's friends crowded around her. She had succeeded in so quieting Mascot that he purred in her arms, and resented none of the attentions bestowed upon him by the victorious seniors. Had he not been fondled and fed by each one of them for over three years?

It was only when strangers approached, that he became restless, and considering that his nerves had received more

than an ordinary shock that day, Janet concluded to take him back at the end of the first game.

"Positively his last appearance upon any stage," she announced as she held him high for a moment. "He retires from public office upon this auspicious occasion."

As she bore him away, there arose three cheers for Mascot from the enthusiastic sophomores, but Mascot was then safe within the familiar precincts of Hopper Hall, and made no demonstration beyond a sudden clutching of Janet's sleeve with his curved claws.

"You are the only girl I ever saw who had a knife sharp enough to cut anything at one fell blow," said Lee as she attended Janet to Hopper Hall. "How on earth did you come by it?"

"My brother Stuart gave it to me the last time he was here," Janet told her. "I had lost mine and he made me a parting present of this."

"It saved the day," declared Lee, "for Jessie would have held on like grim death rather than let Mascot get back to us. Poor little dear he was so scared," she softly stroked the cat's head, "but it certainly gave an added excitement to the morning. I was afraid the faculty would be wrathy, but they really behaved very well."

Janet laughed. "I'd like one of them to hear your superior tone, Professor Weatherby, for example."

"Don't mention him to me," said Lee; "it gives me cold creeps whenever I think of that last exam. No more of those forevermore. Do you dare look for any honors, Janet?"

"Not I. If I get through with a modest number of fair exams, I shall be satisfied. No fellowships nor anything of that kind for this young person. I leave brilliant records for individuals like you."

"Oh, dear," said Lee, "I don't expect to do more than squeeze through. Cordelia is the only one, then, who may look for great things."

"Cordelia probably will take honors," said Janet, "and I shouldn't wonder if Charity did, too."

"Shall we take Mascot this afternoon?" asked Lee.

"No, I think he may be spared any more excitement. We are sure of tennis; the others can't touch us, so there is no use in repeating this morning's performance."

But once more did Mascot appear in public that year, and that was on Class Day when Cordelia read the class will and bequeathed the gray cat to the sister class.

Then while Janet held him, he was divested of his big bow of pink and brown and, with much ceremony, was dressed up in the sophomore colors. Then he was handed over to Madge Ostrom, the president of the sophomores and was borne away in triumph. Yet it must be said that this relinquishing of possession caused more than one pang to the members of the senior class.

"It is the beginning of the end," sighed Lee to Janet as the latter resumed her seat. "How much we shall be giving up."

"And how much we shall be gaining," returned Janet cheerfully. "Think of the lovely feeling of having your mother always close at hand, and the comfortable

knowledge that you can have whatever you want to eat, not to mention the bliss of sleeping late in the mornings, when you are sleepy, without thinking of chapel."

"There are compensations," admitted Lee.

"How lovely some of our girls look to-day," said Janet. "What could be sweeter than our lassies?"

"Molasses," returned Lee promptly.

And Janet almost laughed outright though Charity was at that moment reading a solemn composition in the form of an ode, which, as Janet said afterward, made her feel as if it were not worth while to take any view of life except the old one that they had come to call "the worm's eye view." She lapsed into quite a pensive mood and sat wondering what duties and sorrows lay in the life before her.

Lee, however, speedily recovered her spirits, and vowed that she should allow no one to dwell upon the future, so that because of her gayety no merrier seniors ever enlivened Class Day.

CHAPTER XX

PARTINGS

COMMENCEMENT Day was over and it had passed much as Janet had declared that it would when she arranged her

bulletin for the benefit of Mr. Evans some months before. During the week there was a constant influx of visiting parents, friends, and relatives.

Stuart and a company of his friends were on hand to send flowers and to occupy every moment not necessarily taken up in exercises and ceremonies. Departing students came and went from the various dormitories and lodgings, making farewell calls. Groups gathered about the grounds. Few students were seen walking alone for almost every one had some friend among her classmates from whom it would be hard to part, and the melancholy countenances were beginning to outnumber the merry ones.

As Janet walked arm in arm with Teddy across the campus after the alumnae dinner, she saw Mr. Evans waiting at the gate just ahead.

"Bless me!" she ejaculated.

"What is the matter?" asked Teddy.

"Nothing except that I promised Mr. Evans long ago that I would try to afford him an opportunity to-day to receive my congratulations. I suppose I must walk a little way with him," she said apologetically. "Don't wait for me, Ted. I'll be back before long," and she turned off leaving Teddy to join Cordelia and Lee who were not far behind.

An hour later she came into the twilight quiet of the room where Teddy sat with her elbows on the window-sill gazing out into the dusky street. There were boxes and trunks standing about ready to be sent off in the morning, and overhead was a tramping back and forth. Lee, who had put off her packing till the last minute, was now giving all her attention to getting her trunks and boxes ready. Peals of laughter now and then floated in through the open window,

and up the street came an excited chatter from groups of girls and young men passing by.

Janet seated herself by Teddy's side. "All by her loney, is she? Where is everybody, Ted?"

"Papa and mamma have gone to dine with the Whitelys'."

"Why didn't you go?"

"I didn't want to."

"It is too bad that we must be deprived of the boys' company this evening. Stuart said they must take the seven-thirty if they would reach the university in time for some sort of lark they were going to have. I wonder if we will be as enthusiastic alumnae as they are. The parents wanted to take in all the fun going, so they decided to go on with the laddies and leave me to follow. They actually believed I would be ready to go with them. Mamma understood, but I had hard work making father and Stuart see that I simply could not leave till to-morrow. Come, Ted, let's go up and see the girls. We know Lee is packing, but we also know that Lee would rather have the interruption than not, and maybe we can help her. If we can't be of any use, it will be fun to watch her, and we'll keep Cordelia from badgering her. I am glad there is nothing compelling this evening, and that we are left to follow the dictates of our own sweet wills. The alumnae dinner was quite as much as we could stand after the rest of the excitement."

Bright lights were burning in the rooms overhead which were strewn from end to end with Lee's possessions. "If you can find an inch not already occupied, you may have it," said Cordelia looking around at them from behind a pile of boxes.

"How will I ever get through?" said Lee pausing in her frantic rush. "I have always made it my rule never to do today what I can put off till to-morrow, but there are moments when I wish I were not so virtuous about it. My, but I am warm."

"We will all pitch in and help," said Janet, "and then we'll have time to cool off before bedtime."

"I am too dead tired to move," said Cordelia. "I was ambitious enough to get up early and finish my packing this morning by crack o' day. I knew if I didn't do that, I should find half of Lee's belongings in my trunks when I got home and half of mine would be in hers. I simply had to do it in self-defense, but I feel as if I had not been in bed for a week."

"And we have to start so early," complained Lee. "They will come for the trunks at six o'clock."

"All the more reason that we should get things straightened out so you won't have to be up half the night. Goodness, if my impedimenta cluttered up Teddy's room in this way, I'd hear from her."

"I can't help it," said Lee from the depths of a clothespress. "I thought I had so little that it wouldn't take me any time to pack but I have been dragging out stuff for the last hour and there is no end to it. Where did I get it all? What do I want with it? How am I going to dispose of it? I feel as if I had nightmare."

"Lee's bump of order ought to have developed in all these years she has been pounding away at mathematics," said Teddy, "but I don't believe the bump is one bit bigger. Let me feel, Lee," and she began to tousle Lee's hair,

already in a disheveled condition from frequent divings into closets and trunks.

"Don't get into a scrap, girls," said Cordelia; "it's too warm. There you go, Lee. I knew that tower of boxes would fall before you got them stowed away."

"I'll pick them up," said Teddy, pouncing upon scattered sewing materials, stocks, and ribbons. "Come, Janet, you and I will take one trunk and pack it decently so that when Lee gets home she will at least have part of her wardrobe in presentable condition. You fold and I'll pack."

"Angels of light!" exclaimed Lee gratefully. "You have saved my life."

All three worked away faithfully till finally the room began to assume a more orderly appearance, and Cordelia breathed a sigh of relief. "Oh, you blessed friends in need," she exclaimed, "how I shall miss you. It is a mournful time if one dwells upon it. Even Charity Shepherd broke down this afternoon and as for Pen Robbins, she fairly swam away in her own tears. What shall you do when you get home, Ted?"

"Oh, I don't know. I shall probably be very industrious for a time, and will join clubs of an inspiring nature, and will be so didactic and superior for a year that all my friends will begin to hate me, then I'll gradually ease down till I get like ordinary mortals and it will be possible to live with me. What shall you do, Cordelia?"

"Oh, I suppose I shall teach. Lee and I have a great scheme of getting positions together, but probably she will be in Maine and I will go to Florida; it generally works that way."

"Any one who has received a fellowship as you have done, Cordelia, ought certainly to be able to find a good position nearer home, when she is ready to take it."

"Maybe. I am not planning very far ahead. What do you mean to do, Janet?"

A happy, half dreamy look came into Janet's eyes. "I am not looking ahead very far, either," she replied. "Sufficient unto the day is the joy thereof. I am going to have home and mother first of all, and I want to gloat over them. I want to soak myself in the bliss of being at home for the next month and after that comes Polly and Ted and the Lilly of the field."

"You're not going to be bothered with that Starr child, are you?" asked Lee pushing back her hair from a perspiring face. "I think it is too funny how Janet has always had a silly little freshman tagging after her ever since she became a soph."

"You can't call Polly silly," said Janet on the defensive, "and of course I shall invite Lillie to visit me when she was good enough to have me last Easter. Surely you haven't forgotten that."

Lee clashed a tray into a big trunk and sat down with a sigh of relief. "Of course I remember it," she said reproachfully, "and I think it is high time you told us about that, you provoking secretive creature."

"It is my last chance, isn't it?" said Janet putting her feet up comfortably on a low box. "Well, girls, I will satisfy your curiosity since it is positively our last evening together. The Starrs have the loveliest home imaginable; beautiful grounds and a most artistic interior. Mr. Starr is a man of fine parts, as they used to say, and Mrs. Starr is one of the

most cultivated women I have met for some time. They were simply adorable and I was fêted and entertained without stint. I met several celebrities at their house. I was invited to dine with the governor and altogether I had a perfectly stunning time."

She paused and in a half embarrassed way said: "I don't suppose any of you ever knew that Mark, the perfect man, is a cousin of the Starrs and that he was their guest at the same time that I was."

"Janet Ferguson!" Lee flung down the box she was tying up. "The idea of your never telling us that before. I think that was horridly mean of you."

"Why?" asked Janet. "Are you specially interested in the information?"

"No,—yes, I mean," Lee replied. "I'd have been much nicer to him if I had known."

Janet laughed. "You little wretch. I believe you would, and yet you have always half despised Lillie."

"I haven't really," Lee told her, "but I liked to tease you because you had always been so sly and mum about that visit to her. I took the pains to inquire about her and knew she belonged to the four hundred."

"Then you deserve that I should tell you nothing. I suppose," Janet went on with a show of indifference, "that you all know that Mr. Evans is full professor, or will be next year."

"I heard it rumored, but I did not know that it was an absolute fact," said Cordelia. "I am glad they chose him, for I think he deserves it. How did you hear, Janet?"

"He told me himself this evening."

"Why, of course; you know him quite well after spending ten days in the same house with him. You certainly can't be charged with being expansive, Janet, and yet you aren't usually reticent. I should never have called you an uncommunicative person."

Janet only smiled in reply and Lee announced that as she had no more receptacles for her belongings, that what she couldn't pack, she would have to give away.

"I'll bestow them all upon the washerwoman," she said with a comprehensive sweep of the hand which included the scattered articles remaining upon bed, chairs and floor. "Let's go into the other room; it's pretty well stripped, but it is cooler than in here."

"It is still cooler in our rooms," said Janet, "for we haven't had any lights. You two had better come down there and cool off."

"I couldn't," said Lee. "Every bone in my body aches. I might get there by sliding down the balusters, but I never could get back again. No, thank you, Janet; I'll stand by the old ship till I have to be taken off by a life-line."

Teddy and Janet lingered by the door with many words of regretful parting, and then went down to their own rooms.

"Well, Ted, it's all over; we are no longer undergraduates," said Janet, striking a match and lighting the gas.

"And this is the last evening you and I will ever be here together," said Teddy, with a catch in her voice.

Janet turned and looked at her.

The tears were running down Teddy's cheeks. "Why, Ted, why, Ted," she said commiseratingly.

"Oh, I know it doesn't mean so much to you," said Teddy, reckless of disclosing her real feelings. "You never cared very much. You always loved Polly more, and even Lillie, but I loved you best, Janet. I always did. Nobody else ever came first, and now we are going to part and you will drift away from me altogether. We shall never be classmates and roommates as we have been in this old place; never again."

"Why, Ted, why, Ted," Janet spoke in an expostulatory voice, for Teddy was now sobbing broken-heartedly.

"It is all true," said Teddy. "You never loved me half as much as I have loved you."

Janet knelt down by the side of the bowed figure and put her arms around the weeping girl. "You dear Teddy," she said, "just because I am so used to you and haven't been demonstrative, do you think I don't care? Do you think that any one will ever quite take your place? Teddy, why you are a part of me, almost. I shouldn't think of making much fuss over my own right hand for example. Have you felt that way all along? Have you been hurt and indignant when I have made love to Polly? Have you, Ted? Have I hurt you?"

"Sometimes," acknowledged Teddy with tears in her voice.

"You dear old goose, don't you ever feel so again. Don't cry, Ted, you blessed old stand-by. I shall have to do without Polly and I shall be able to very well, and as for Lillie I don't care a picayune about that baby's

blandishments, but Ted, I could never get along without you. Don't you believe me?" She drew Teddy closer to her and snuggled her face down against the wet cheek. "Please don't cry, Ted," she urged.

"I won't if I can help it," said Teddy sitting up and drying her eyes, "but now I have started, I don't seem to be able to stop. I know I am silly, Janet. I don't usually make such a show of myself, do I? But," the tears flowed again, "it's so hard to part from you," she sobbed.

"But you believe that I love you, and that you must always come first among all my girl friends, you do believe it?"

"Yes, I do now."

"And you are satisfied?"

"Yes, oh, yes. Kiss me, Janet; you never do, you know."

Janet put her arms around her and kissed the trembling lips again and again, the tears standing in her own eyes. "We are going to see each other again in a month, remember," she said, "and Ted, let me tell you something; I'd rather have you for my sister than any girl under the sun. I think I hope some day you will be. Do you hope so, too, Ted?"

Teddy did not answer, but buried her face on Janet's shoulder. "Stuart never liked a girl so well as he does you," Janet went on, "and when he has finished his medical course, why then, Ted—"

"Don't say any more," pleaded Teddy in muffled tones, "or I shall cry again."

"There's something else I want to tell you," Janet continued. "Not another soul knows it. Ted, I don't think this is the last time we shall be together in this old town, for Ted —"

Teddy lifted up her head. "Janet, I believe I can guess; it is Mark, the perfect man."

Janet nodded, then said hastily: "Oh, not yet. Some day, two or three years from now, maybe. He—he told me this evening. I didn't suppose," she continued half to herself, "that was what he meant by its being encouraging."

"What encouraging?"

"I told him once that if I ever had to choose another place of residence than my own home I'd prefer this to any. Wasn't I a goose to tell him that? But I never dreamed then."

"Dreamed what?" Teddy was never very subtle.

"That he—that he would say what he did this evening. I never began to suspect till last Easter when we were both at the Starrs'."

"You never told me that he was there," said Teddy reproachfully. "You might have trusted me, Janet."

"I know I might, but I couldn't. I was half scared and half happy and I wasn't sure and I remembered 'the hero,' and so I made Lillie promise that she wouldn't say anything about it, because she was beginning to tease me and I told her it might be the means of breaking up my friendship with Mark—the perfect man, I mean. I was just in that state of mind when a little too much one way or the other would have made all the difference in the world, so I scared her

into keeping quiet about it, and I wouldn't let him see me very often for the same reason. I've told you first of all, Ted, and that is why I can't cry to-night; I am too happy."

By common consent, they moved toward the dimness of the outer room, and sat together by the window, arms on sill and heads touching. The twinkling lights of Hopper Hall on the other side of the college campus began to disappear one by one. The tramping up-stairs had ceased.

From the gardens across the way came a night breeze rose-sweet. The honeysuckle climbing over the porch below the window, sent up a waft of perfume now and then from its few opened buds. A rapid footstep echoed along the pavement once in a while. Then came silence and the coolness of the night's late hours. The two girls sat without speaking for a long time, then Janet arose and laid a caressing hand on Teddy's head.

"It's all over for Cordelia, and Lee and the others, but for me it has just commenced. There will be much more of it in the years ahead of us, Teddy, for where I go you will have to come."

Presently their lights, too, were out, and only the shining stars looked down upon the sleeping town.