https://ebookmass.com/product/disruption-why-things-change-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Disruption: Why Things Change David Potter

https://ebookmass.com/product/disruption-why-things-change-davidpotter/

ebookmass.com

Strategy in the Age of Disruption: A Handbook to Anticipate Change and Make Smart Decisions 1st Edition

Henrik Von Scheel

https://ebookmass.com/product/strategy-in-the-age-of-disruption-ahandbook-to-anticipate-change-and-make-smart-decisions-1st-editionhenrik-von-scheel/

ebookmass.com

One

Good Thing Alexandra Potter

https://ebookmass.com/product/one-good-thing-alexandra-potter/ ebookmass.com

Me■decine physique et de re■adaptation 6e édition. Edition Cofemer

https://ebookmass.com/product/medecine-physique-et-dereadaptation-6e-edition-edition-cofemer/

ebookmass.com

Christians and Others in the Umayyad State Antoine Borrut

https://ebookmass.com/product/christians-and-others-in-the-umayyadstate-antoine-borrut/

ebookmass.com

Lean Game Development: Apply Lean Frameworks to the Process of Game Development 2nd Edition Julia Naomi Rosenfield Boeira

https://ebookmass.com/product/lean-game-development-apply-leanframeworks-to-the-process-of-game-development-2nd-edition-julia-naomirosenfield-boeira/

ebookmass.com

Beasts of Burden: An M/M Fantasy Romance (The Black Blade Chronicles Book 2) J.K. Hogan

https://ebookmass.com/product/beasts-of-burden-an-m-m-fantasy-romancethe-black-blade-chronicles-book-2-j-k-hogan/

ebookmass.com

Economics: Private & Public Choice 17th Edition James D. Gwartney

https://ebookmass.com/product/economics-private-public-choice-17thedition-james-d-gwartney/

ebookmass.com

Life in Early Medieval Wales Nancy Edwards

https://ebookmass.com/product/life-in-early-medieval-wales-nancyedwards/

ebookmass.com

Sister Saints: Mormon Women Since the End of Polygamy

Colleen Mcdannell

https://ebookmass.com/product/sister-saints-mormon-women-since-theend-of-polygamy-colleen-mcdannell/

ebookmass.com

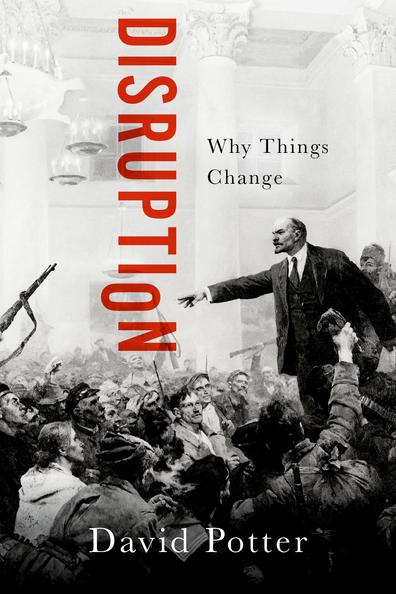

DISRUPTION

Why Things Change

David Potter

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Potter, D. S. (David Stone), 1957–author.

Title: Disruption : why things change / David Potter. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020036736 (print) | LCCN 2020036737 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197518823 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197518847 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Social change. | Creative destruction. | Human behavior. Classification: LCC HM831.P686 2021 (print) | LCC HM831 (ebook) | DDC 303.4—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020036736

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020036737

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197518823.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

A.A. et W.G.F. in memoriam

CP-S et N.P. amore

ILLUSTRATIONS

Dome of the Rock (Shutterstock)

Coin of ‘Abd al-Malik (American Numismatic Society)

3.1. Martin Luther (Shutterstock)

3.2. Charles V

3.3. Henry VIII

3.4. Thomas Cromwell

3.5. Mary Tudor

3.6. Elizabeth I

3.7. William of Orange (Shutterstock)

4.1. Rousseau

4.2. Washington

4.3. Robespierre

5.1. Karl Marx in his London period (Shutterstock) 210

5.2. Herbert Spencer in his early years 217

5.3. Francis Galton in the 1850s 223

5.4. Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov Lenin in 1920 (Shutterstock) 234

5.5. Adolf Hitler and Paul von Hindenburg (Shutterstock) 269

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book was inspired by my tenure of the Ronald J. Mellor chair in Roman History at UCLA. I would especially like to thank Steve Aaron, who stressed the importance of history as an outward-looking discipline, for creating the environment in which I could conceive of a project which is very different from any other that I have attempted in the past. My colleagues Joan Waugh, Stefania Tutino, Bill Marotti, Teofilo Ruiz, and Nile Green provided further inspiration for the project, as did my immediate, classically inclined colleague, David Phillips. The book was finished in my usual home, the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan, where Sara AhbelRappe and Lisa Nevett listened kindly as I rambled on about what I was doing. It is a particular pleasure to thank Tim Hart, who read through much of the manuscript at an early stage, contributing many helpful comments, as did George Woudhuysen at the University of Nottingham (neither of whom can be blamed for eccentricities that remain); Arianna Zapelloni Pavia read through the whole text at a late stage, saving me from a number of errors. Brittany Pendergraft provided invaluable assistance with the proofs.

Stefan Vranka at Oxford University Press nurtured this project from its earliest stages as the object of dinnertime conversation in Los Angeles through its conclusion, providing excellent editorial advice and seeking immensely helpful input from readers whose attention to detail has made this a much better book.

My wife Ellen has, as always, put up with the burden of the project, stacks of books piling up around the house, and rather a lot of discussion of the unsavory characters who fill the pages that follow. This would not be the book it is without her.

Finally, it seems appropriate in dedicating this book to look ahead and back. As I write, two old friends look over my shoulder from photos taken long ago, men who guided my early steps as an historian and who always stressed the civic importance of historical understanding, George Forrest and Tony Andrewes. Looking to the future and to what will, I hope, be a better, stronger world, the book is also dedicated to two people who bring joy to my life and Ellen’s every day: Natalie and Claire.

Introduction

How do things change? Answering this question is a fundamental mission of historical study. It is also a profoundly important question to consider today, as the liberal democracies that set the tone for social and economic development over the past seventy years are facing extraordinary challenges. The convergence of increasing economic disparity and political fragmentation, the presence of alternative economic models offered by superficially successful totalitarian states, and a devastating disease are once again creating conditions in which a disruption like those that are the subject of this book can occur. Disruptive change always begins on the fringes of society. Throughout time, the “mainstream” has been inherently conservative. Stable societies allow for incremental change but are essentially dedicated to the preservation of existing power structures. In such cases, dominant ideologies justify existing relationships. In the historical studies that follow, we will see how ideologies that develop in reaction to the ones supporting the status quo are necessary to guide profound changes in political and intellectual structures. A study of radical change is also a study of societies in which central institutions have failed and fundamental affiliations are severed.

Not all radical groups are the same, but all the groups that we will be examining take advantage of mistakes that challenged belief in the competence of existing institutions. The coincidence of an

alternative ideological system with a period of community distress is the necessary condition for radical change. The agents of change are not the downtrodden and distressed, the disadvantaged or disenfranchised. They are inevitably members of a dominant political class who, when successful, take advantage of existing thought systems to create a new ideology of legitimacy. That said, they would not have succeeded in what they were trying to do if they were incapable of bringing large numbers of people along with them, if they were incapable of speaking a language that people outside their circles could understand, and were not speaking to basic concerns in the broader population.

An important point that will emerge from our studies is that disruptive actions do not always follow paths their original proponents might have predicted. Our studies, therefore, examine structures that can either facilitate or derail change.

A word that I’m deliberately avoiding in discussing “disruptions” is “revolution.” One reason for this is that revolutions are very hard to define. In scientific terms, a revolution is simply a completed cycle. In political terms, “revolution” can be used as a synonym for civil war, regime change, or reform movement. Just as easily, it can mean the “substitution of a new system of government” or a “complete change of ideas or methods.” Although some of the events I’ll be discussing are routinely called revolutions, we’ll see that “disruption” is a better term. The French “revolution,” for example, substituted an imperial autocrat (Napoleon) for a king, and, when Napoleon was defeated, saw the restoration of the royal family that had been ousted prior to Napoleon’s rise to power. What was thoroughly disrupted in the course of all of this was not autocracy as a form of government, but the system that had sustained the autocracy. In France’s case this was the alliance between the nobility and the Catholic Church, upon which the monarchy had depended since the Middle Ages. The result of the Bolshevik “revolution,” which

we’ll explore in Chapter 5, for all its rhetoric of social revolution, was the replacement of an incompetent monarch whose authority rested upon increasingly fragile insitutions with a totalitarian dictator. What was disrupted was a traditional way of defining power. That is why the Bolshevik seizure of power differs significantly from the rise of the Communist Party in China, although that too is often referred to as a revolution. But the rise of the Communist Party in China did not involve the overthrow of the ancient imperial political order, which had collapsed decades earlier. Rather, it was the result of the communist victory over the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) in what was effectively a contest between two ghouls for control of a corpse. As the example of the French or, as we’ll also see, Nazi disruptions show, successful parties might not create stable new institutions—but the result of the disruption was that it was impossible to go back to the way things had been.

The successful parties in the disruptions we’re looking at in this book are groups who made use of novel ideologies to stabilize their positions. Some of those who failed to create stable new situations did so because they placed ideological correctness ahead of the practicalities of governance. They also lacked, in some cases, the capacity to understand that radicalism unrestrained by realism is inherently self-destructive.

Understanding disruption as a strategy employed for selfadvancement on the part of a politically active group means that there is no necessary precondition of socioeconomic dislocation. Students of “revolution” look for explanations in deep structural imbalances, such as the coexistence of incompatible economic systems within a single political entity (e.g., peasant farming and capitalist enterprise). My point is that serious disruption requires the successful exercise of self-interest on the part of the winning side, and that disruption is not the inevitable result of economic change. Economic dislocation can create a problem, but it does not dictate the solution.

Our first two studies will be ones in which the changes were disruptive, successful, and of continuing importance today. These are the emergence of Christianity and Islam as world religions.

The transformation of Christianity from a relatively successful minority cult into a world religion was accidental. The catalyst was a Roman emperor, Constantine, who was trying to solve some problems of his own. He needed to create a narrative to justify his seizure of power at a time when traditional political ideologies had been pretty thoroughly shattered by domestic instability and military failure. He drew upon ideas that had been developed by some of his recent predecessors as a way of creating a myth of legitimacy, chiefly by claiming the favor of a particular divinity.

Constantine chose the Christian God as his protector for quite specific reasons, then worked with a small number of Christians to provide his new religion with an intellectual and institutional framework that could shape the political discourse of his age. It is quite possible that, by the end of his life, Constantine envisaged the possibility that his empire could become a predominantly Christian institution. But the creation of the institutions that made this possible was a process of trial and error. One very important point is that once he had shaped the Christian movement into one that could achieve universal significance, Constantine showed considerable wisdom in leaving the process of conversion to individual consciences.

The emergence of Islam underscores the importance of a number of factors we saw with the rise of Christianity. But there are some important differences. Perhaps the most important was that Constantine made use of ideas that had been in circulation for three centuries after the career of Jesus. There was a long history of interpretation that had already shaped the Christian community before Constantine’s intervention. The rise of Islam, on the other hand, was the product of the generation that followed upon those who had known the Prophet themselves.

The circumstances that led to Muhammad’s revelation were quite similar to those that lay behind Constantine’s adoption of Christianity. Muhammad lived at a time of profound dislocation, in this case caused by an ecological catastrophe followed by the immensely destructive wars waged between the Persian and Roman empires, the two superpowers of his time and place. Muhammad adapted teachings that were well established within the Arabia of his lifetime to unite and inspire his followers to dominate the better part of the Arabian peninsula. At this point, Muhammad died, and the movement was taken up by the companions of the Prophet who took advantage of the self-inflicted wounds suffered by Rome and Persia to sweep existing power structures aside. The rapid collapse of Persia and the withdrawal of Rome made it necessary for the leaders of Muhammad’s movement to find a way to turn his revelation into a series of governing principles— a task which, although not without some hiccups, they accomplished. There will appear to be much in common between the decisions made by ‘Abd al-Malik, who stabilized the new Arab empire and shaped Muhammad’s message into the ideology of a governing party, and those taken by Constantine. There will also be obvious points of contact between the actions of the Roman emperor Heraclius and the leadership that confronted the Protestant Reformation in our next chapter.

Underlying the disruption caused by the Protestant Reformation was, again, a sense of weakness and unease as the rise of the aggressive Ottoman empire in the Mediterranean and Central Europe was balanced against rumor (and reality) of the discovery of new lands and trade routes. During this same time, the leaders of the two great institutions of the time, the Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire, were increasingly detached from the reality of the world in which they were seeking to function. In the case of the Holy Roman Empire, the situation would be further complicated by the fact that,

in 1519, its ruler would be the nineteen-year-old Charles V. And there was a new technology, printing, first used by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439. The invention of moveable type made mass communication possible in new ways. Without the printing press, it is scarcely feasible that the statements of an angry clergyman from southern Germany, Martin Luther, could have obtained European significance with such great rapidity, or that many people at all would have learned of the ninety-five theses he posted in 1517. Important support for Luther’s thought derived from the work of earlier humanists who had begun the rational recovery of ancient knowledge and questioned the intellectual authority asserted by the Catholic Church in the centuries after the rise of Islam.

Although Luther’s views on the Catholic doctrine of Purgatory (that it didn’t exist) and the saving power of God’s grace were extreme, his movement gave rise to even more extreme revisionist movements which aimed at overthrowing the social order. While Luther resisted the further radicalization of his views, a fact that made it possible for German princes to support him, the explosion of radicalism to extend or suppress a transformative movement is characteristic of major disruptions. The tendency of the political center to collapse toward extremes at either end of the spectrum is one that we will see in other studies, and would inform the reception of the Reformation outside of southern Germany.

When we look at the reformations in the two most successful Protestant states of the sixteenth century, England and the Netherlands, we will see the struggle between centrist and extremist reformers. The central role of the king (Henry VIII) or queen (Elizabeth I) in England meant that the most radical forms of Protestantism were outright rejected by the most effective leaders of the Reform movement. In the Netherlands, William of Orange was able to transform two extremist forms of post-Lutheran Protestantism, which had inspired resistance to the Catholic regime,

from potentially destructive forces to the ideological support system for a new system of government that encouraged freedom of conscience as a fundamental feature of the new state. In both Britain and the Netherlands, the Reformation’s impact depended upon the ability of dedicated groups of professionals to transform a series of revolutionary statements into principles that could be used to create a unified society.

Although Luther saw himself as a religious reformer, the movement he initiated was profoundly disruptive not only because it insisted that evidence-based thinking replace religious dogma as a path to better understanding, but because it enabled the development of states that upset the European balance of power. The linkage between national identity and conscience that derived from the Reformation, in both Protestant and Catholic lands, encouraged new thinking derived from secular, usually Greco-Roman, political theory in place of the Bible, making it possible to rethink the relationship between government and its subjects. This change laid the foundation for our next great disruptions, the rise of participatory democracy and the demise of royal absolutism.

The idea that a state should have a written constitution based on the idea of “popular sovereignty” is quite a remarkable one. Largely derived from classical models by thinkers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the idea became foundational in a moment of profound political experimentation at the end of the eighteenth century. The way theory was linked to practice is the subject of our fourth study, or pair of studies. One of the issues we’ll be confronting here is why essentially the same sets of ideas worked very well in one case, and failed miserably at almost exactly the same time in another. Our starting point for this study will be 1783, the year the Treaty of Paris ended English rule over thirteen of its North American colonies. The end of centuries of colonial rule was a big disruption; the successful development of a federal government was an unexpected

consequence for a movement that began as a protest against government overreach.

The Netherlands had been established by the Union of Utrecht in 1579, but that document was an alliance between independent entities for purposes of self-defense. The constitution of the United States was a response to the failure of the confederation of states that had come into existence in the wake of the war ending English rule over these thirteen former colonies. The constitution that was then adopted was the product of a small group of dedicated individuals who drew upon earlier political theory as well as their own practical experience to shape the charter for a new nation. It was explicitly a revolutionary document, but it was also the product of a series of compromises. The framers of the Constitution were profoundly practical men seeking to fix a system of government that didn’t work. Where reality didn’t align with theory, theory lost. That is why the Constitution of the United States protected slavery.

The behavior of the framers of the United States Constitution stands in stark contrast to the conduct of the leaders of the movement that, beginning in 1789, initiated an effort to replace the traditional French monarchy with a modern parliamentary government. Although many French leaders were familiar with the ideas that shaped thinking in the United States, and although there were similar structures, including small cadres of committed individuals looking to adapt contemporary political theory to practical purposes, external pressures, and lack of consensus led to the failure of democratic impulses. The result of this failure was the development of, first, a homicidally inclined dictatorship, and then the Napoleonic system.

One important difference between the framers of the US Constitution and the reformist leaders of France was that the former had worked together in running a successful war against the world’s most powerful state, while in the latter case, the members of the Committee of Public Safety operated in an atmosphere of

ever-increasing mistrust, manipulating hostility to partisan advantage. Another point of contrast lay in their respective understandings of direct democracy. The framers of the Constitution were familiar with democratic voting processes at the local level. They distrusted it, played down its institutional impact, and created a framework within which a political society could grow. French radicals saw democracy as the theoretical opposite of monarchy. They moved rapidly to establish institutions that depended upon responsible voting behaviors despite the fact that most people in France had never voted in an election. That was a disaster. Politics moved rapidly to the extreme, and we see in action—even more clearly in the French experience than in the Reformation—the tendency for radical theory to so transform a debate that centrist positions collapse.

One impact of the great French disruption was the creation of a new way of fighting wars, drawing upon all of a society’s resources. The horrors of the conflicts they initiated helped focus the attention of several generations of European leaders on the importance of peace and more limited conquests. Gradually, however, the destructive lessons of the past were forgotten, and there was a widespread failure to appreciate the ruinous potential of the new generations of weapons spawned by the Industrial Revolution. The result of this amnesia and blindness was disaster. There can be no more powerful example of the way bad planning has unexpected consequences than the impact of the errors made by the leaders of Russia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Germany in July and August 1914. All three states descended from entities that had existed for five hundred years, and all three ceased to exist by the First World War’s end in 1918.

The horrendous human cost of this war resulting from the industrialization of the previous half-century was accompanied by a belief that science was a rational process. Fascination with progress stemming from the physical sciences led to efforts to understand human

society in “scientific terms,” giving rise to a pair of particularly powerful theses. One was the idea of an inevitable evolution of mankind from the slave societies of antiquity to a post-capitalist, socialist future. The other, tangentially derived from Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, was the theory of the “survival of the fittest” popularized by Herbert Spencer. By some, Spencer’s theory was taken to mean that “weaker” races would disappear before stronger races.

The destruction of the First World War enabled the creation of regimes in the failed states of Germany and Russia that claimed to apply the results of theory to practice. In the rise of Bolshevism and Nazism, we see many of the basic structures we have seen in other periods of disruptive change. These are the collapse of central institutions, accompanied by the twisting of existing theories into governing ideologies. The fact that the ideas of both Lenin and Hitler were widely resonant in the intellectual world of their time made it difficult for outsiders to perceive the particular turn that each had taken. Marx never advocated terror, and social Darwinists, as Spencer’s followers came to be known, did not typically advocate racial mass murder. But that did not mean that ideas descended from theirs could not move in this extremely destructive direction. Both Marx and Spencer based their doctrines on notions of struggle, and struggles will have winners as well as losers.

Three points emerge from these studies. One is that ideas around which disruptive movements coalesce are already present in society, though typically imbedded in marginal or fringe elements. The second is that all these thought systems represented a repudiation of the principles that had governed daily life, setting their insights and ideas over and above the existing order and traditional definitions of legitimacy. Finally, in each case, change is driven by a group tightly organized around a charismatic leader, who saw himself as creating a new political order based upon the disruptive thought system identified with an earlier thought leader.

The overall model of change that emerges from our historical studies is not dissimilar to that which informs aggressive contemporary developments in the business community. Innovation tends to come from small companies. These start-ups are absorbed by larger corporations where change has otherwise become an incremental process that simply reinforces a status quo. This pattern is especially clear in the world of technology, where small groups of pioneers drive the ongoing digital revolution and large companies, tied down by the interests of existing customers, cannot justify to themselves the costs of potentially fruitless innovation.

The early twenty-first century is a time when a culture of “disruption” has strengthened radical political movements that aim to alter the existing world order. Major shifts in the political landscape often take their directions from mantras of the business world (e.g., “change is important”) to offer increasingly radical alternatives to “the establishment.” In recent years, this has been the case with “Tea Party” Republicans and the increasingly potent “democratic socialist” wing of the Democratic Party. In Europe, the normalization of nationalist groups such as Alternative für Deutschland, the Rassemblement national, or Viktor Orban’s Fidesz Party are threatening established political norms. They are dragging more centrist groups away from their base, and eliminating space for compromise while promoting demographic myths based on fantastical images of immigration. And then there is the United Kingdom, where “Brexiteers” have translated traditional English exceptionalism into a destructive form of hyper-nationalism. The ideology of Brexit, like that of Donald Trump’s supporters, echoes the doctrines of late nineteenth-century social Darwinists with fantasies very similar to those activating most extreme movements in contemporary Europe. Instead of focusing anger on delusions about migration and fabricating threats of terrorism that “justify” violent police tactics, it might be more reasonable to fasten attention on the impact of monopolistic “surveillance