OXFORD

UNIVERSITY PRESS

G reat Cla ren don Str eet, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdo m

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthe rs th e University's objective of excellence in resea rch, scholarsh ip, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxfo rd Univers ity Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Susanne Bobzien 202 1

The m oral rights of the author have been asserted Fir st Edition published in 2021

Impression: I

All rights reserved. No part of thi s publication may be reproduced , stored in a ret r ieval sys te m , or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford Un iversity Press, or as exp r essly permitted by law, by licence o r unde r terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organ ization. Enquiries conce rning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to t he Righ ts Department, Oxford U niversity Press, a t th e address above

You m ust not circulate t his work in any other form and you must impose th is same co ndition on any acquir er

Published in the Un ited States of America by Oxford Uni versity Press 198 Madison Ave n ue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Da ta ava ilable

Library of Congress Control Number: 20209460 11

ISBN 978-0- 19- 886673-2

DO I: 10.1093/ oso/9780 198866732.001.0001

Printed and bound by CPI Group (U K) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaim s any responsibility for the materials contained in any thi rd party website refe renced in thi s work.

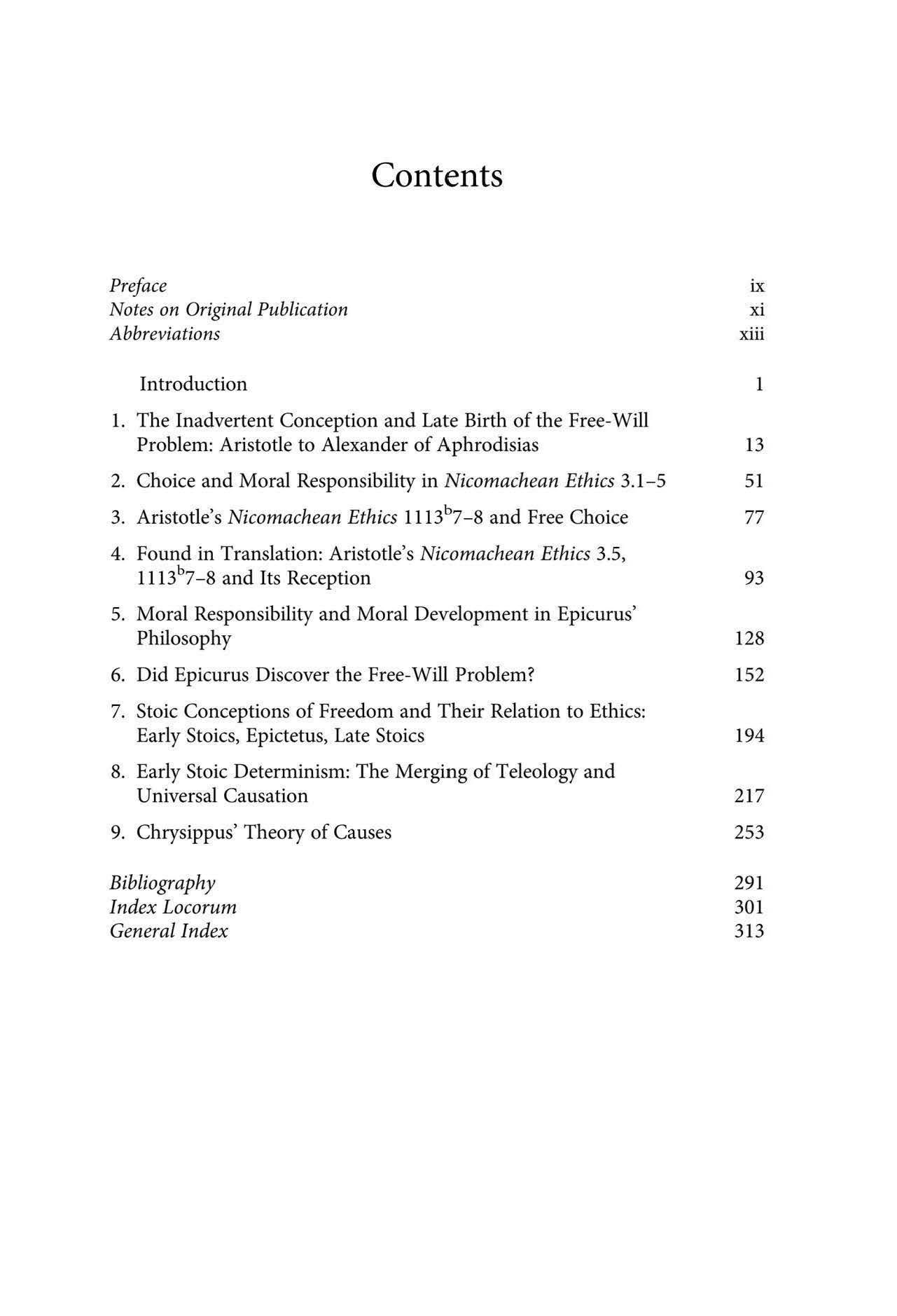

Contents

Preface

Notes on Original Publication

Abbreviations

Introduction

1. The Inadvertent Conception and Late Birth of t h e Free-Will Problem: Aristotle to Alexander of Aphrodisias

2. Choice and Moral Responsibility in Nicomachean Ethics 3.1-5

3. Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics ll 13b7-8 and Free Choice

4. Found in Transl ation: Aristo tle's Nicomachean Ethics 3.5, 1113 b7-8 and Its Reception

5. Moral Responsibility and Moral Development in Epicurus, Philosophy

6. Did Epicurus Discover the Free-Will Problem?

7. Stoic Conceptions of Freedom and Their Relation to Ethics: Early Sto ics, Epictetus, Late Stoics

8. Early Stoic Determinism: The Merging of Teleology and Un iversal Causation

9. Chrysippus' Theory of Causes

Preface

Thenineessaysinthisvolumewerewrittenoveraperiodofclosetotwentyyears. Theywerenotenvisaged,letaloneplanned,tobepublishedtogetherasabook, but,withhindsight,theyholdtogetherratherwellandadequatelypresentmy overallviewandinterpretationsofdeterminism,freedom,andmoralresponsibility inantiquity,inbothitsphilosophicalandhistoricalaspects.Theninechaptersin thisvolumecomprisealltheessaysIhavewrittenonthesetopicstodate,withthe exceptionofbookreviews,encyclopediaarticles,repliestopapers,andan afterword.

Thechaptersareorganizedinfourparts,mostlyaccordingtothechronologyof theancientphilosopherswhosepositionsaretheirsubjectmatter,fromAristotle viaEpicurustotheStoics,withanoverarching firstchapterthatcoverstheperiod fromAristotletoAlexanderofAphrodisias,theearlythird-century Peripatetic commentator.Withineachpart,theorderisfromthegeneraltothespecific,from theeasilyreadtodetailedscholarlyanalysis.Chapters2,5,and7(and8)canbe usedasanintroductiontotheviewsofAristotle,Epicurus,andtheStoics, respectively.Allchapterscanbestudiedindependentlyofeachother.Thissaid, readingthe firstsection,orthe firstfoursections,ofChapter1mayfacilitatethe understandingofthelaterchapters.Chapter1alsoprovidesausefulintroduction tomyphilosophicalandhistoricalapproachtothephilosophersdiscussedinthe volume.

NoknowledgeofGreekorLatinisrequiredforreadingthemaintextofthe chapters.GreekandLatinpassagesaretranslated.Thetextsintheiroriginal languageareplacedinfootnotesforconsultation,andallGreekexpressionsare transliteratedinthemaintext,exceptinrareinstanceswheremattersoftranslationarethemselvesthetopic,asisthecase solely inChapter4.

Someminorchangeshavebeenmadetotheessays,mostlyfortheconvenience ofthereader.Thus,IhaveaddedGreekandLatintextsinstarredfootnotesina numberofplaceswhereonlytheEnglishwasoriginallygiven.Conversely,Ihave addedEnglishtranslationsinanumberofplaceswhereonlytheGreekorLatin originalwaspresent.Ihavealsotranslatedsomeuntranslatedcontemporary languageelementsintoEnglish.Typosandsimilarminorerrorshavebeen corrected,and,inplaces especiallyintheearlieressays Ihavemadethe Englishmoreidiomatic.Whereonrereadingaphraseorsentenceappearedto meambiguous,Idisambiguated.Thecrypticallyshortlasttwoparagraphsof Chapter9havebeenexpanded.Chapter8,section8.4,whichhadtobeshortened forits firstpublicationduetoawordlimit,hasbeenrestoredroughlytoitsoriginal

length.Throughoutthevolume,someelementsofpresentation,suchaslayout, numbering,citations,andthelikehavebeenunified.Asfaraspossible,the originalfootnotenumbershavebeenretained.WhereGreekorLatintextsetc. havebeenaddedinnewfootnotes,thesefootnotesarestarredratherthannumbered.Squarebracketsinatranslationindicateaphrasesuppliedbycontext. Angledbracketsintextandtranslationareusedtoindicateatextualemendation. Alistofabbreviationsusedfortheancienttextsisgivenonpagesxiii–xv.

Since1997,whenthe firstoftheessaysinthisvolumewasoriginallypublished, therehasbeenavastnumberofpublicationsonquestionsofdeterminism, freedom,andmoralresponsibilityinantiquity.Thisisnottheplacetolistthem all,norwillIhererespondtoindividualpapersandbooks.(Itisgratifyingtosee thatthemajorityofresponsestotheessayscollectedherehaveagreedwithmy maintheses.)Inthisvolume,Irestrictmyselftomentioningafewrecentbooklengthstudiesandcollectionsthatwillprovidethereaderwithadditionalinformationaboutthedevelopmentsinlateancientphilosophyandinareasthatare coveredneitherintheseessaysnorinmybook DeterminismandFreedominStoic Philosophy.

Precursorstoeightofthepaperscollectedherewere firstpresentedonthe occasionofalectureIhadbeeninvitedtogiveorasaconferencecontribution,and Iamgratefultothosewhoissuedtheinvitations.(Theninth,Chapter9,isa substantial offshootfrommybook Determinism.)Thosewhohelpedformthe finalproductswithprobingquestionsandlearnedcommentsattheseoccasions, andsometimesbeforeorafter,onwalks,ontrains,incafes,inemails,are acknowledgedineachpaper,althoughIhavedoubtlessoverlookedsomepeople hereandthereandcollectivelythankthematthispoint.Forthiscollectionasa whole,Iam firstofallmostgratefultoPeterMomtchiloff,whoencouraged publicationoftheseessaysasavolumeandwhohasprovidedvitalassistanceat variouspointsduringitscomingintobeing.Iamalsoindebtedtotheeminently competentPaulScade,whowasagreathelpinputtingtheseessays which displayedalargevarietyoflayoutsandeditingconventions intoaconsistent form,andassistedwithvariousissuesrangingfrompunctuationtoidiomaticity. ThanksgoalsotoChiaraMartiniformostadeptlyandreliablyhelpingingetting theGreektransliteratedoruntransliteratedasthecaserequired,aswellasfor assistancewithrestoringtextsfromPDFsandforproofreadingagainstthe originalpapers.NathanA.Schatzhasbeenasteadysourceofsustenance,a paragonofpatience,andmuchmore.

NotesonOriginalPublication

Theessaysofwhichtheninechaptersinthisvolumearerevisedversionswere first publishedinthefollowingplaces:

1. Phronesis 43(1998),133–75.

2.R.Polansky(ed.), TheCambridgeCompaniontoAristotle’sNicomacheanEthics (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2014),81–109.©RonaldPolansky2014, publishedbyCambridgeUniversityPress.

3.P.Destrée,R.Salles,andM.Zingano(eds), WhatIsuptoUs?StudiesonCausalityand ResponsibilityinAncientPhilosophy (SanktAugustin:AcademiaVerlag,2014).

4. OxfordStudiesinAncientPhilosophy 45(2013),103–48.

5.B.ReisandS.Haffmans(eds), TheVirtuousLifeinGreekEthics (Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,2006),206–29.©CambridgeUniversityPress2006.

6. OxfordStudiesinAncientPhilosophy 19(2000),287–337.

7.R.Sorabji(ed.), AristotleandAfter (London:InstituteofClassicalStudies,1997), 71–89.BypermissionofOxfordUniversityPressonbehalfoftheInstituteofClassical Studies.

8. Revuedemétaphysiqueetdemorale 48(4)(2005),489–516.

9.K.Ierodiakonou(ed.), TopicsinStoicPhilosophy (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress, 1999),196–242.

Theauthorisgratefultothepublishinghouseswhogavepermissiontousematerialthat isintheircopyright.

Abbreviations

Aetius Plac.Aetius DePlacitaPhilosophorum

Alcinuous, Didasc.Alcinous, Didascalicos

Alex. An.Pr.

Alex. Fat.

AlexanderofAphrodisias, CommentaryonAristotle’sPrior Analytics

AlexanderofAphrodisias, OnFate

Alex. Mant. AlexanderofAphrodisias, Mantissa

Alex. Mixt. AlexanderofAphrodisias, OnMixture

Alex. Quaest. AlexanderofAphrodisias, Quaestiones

Alex. Top. AlexanderofAphrodisias, CommentaryonAristotle’sTopics Ammonius, Int.Ammonius, CommentaryonAristotle’sdeInterpretatione

Anon. EN anonymous, CommentaryonAristotle’sNicomacheanEthics

Apuleius, Plat.Apuleius, DePlatoneetdogmateeius

Aquinas, Sent.Eth. ThomasAquinas, SententialibriEthicorum

Arist. An.Pr. Aristotle, PriorAnalytics

Arist. Athen.Const.Aristotle, ConstitutionoftheAthenians

Arist. DA Aristotle, DeAnima

Arist. EE Aristotle, EudemianEthics

Arist. EN Aristotle, NicomacheanEthics

Arist. Int. Aristotle, DeInterpretatione

Arist. Metaph. Aristotle, Metaphysics

Arist. Phys. Aristotle, Physics

Arist. Rhet.Aristotle, Rhetoric

Arist. Soph.Elen. Aristotle, SophisticalRefutations

Arist. Top. Aristotle, Topics

Aspasius, EN Aspasius, CommentaryonAristotle’sNicomacheanEthics

Augustine, Deciv.D. AugustineofHippo, DecivitateDei Augustine, Lib.arb.AugustineofHippo, Deliberoarbitrio

Boethius, Int. Boethius, CommentaryonAristotle’sdeInterpretatione

Calc. Tim.Calcidius, OnPlato’sTimaeus

Cic. Acad.Cicero, Academica

Cic. Div. Cicero, OnDivination

Cic. Fat.Cicero, OnFate

Cic. Fin.Cicero, OnEnds

Cic. Mur.Cicero, ProMurena

Cic. Nat.D. Cicero, OntheNatureoftheGods

Cic. Top. Cicero, Topics

Clement, Strom.ClementofAlexandria, Stromata

DLDiogenesLaertius, LivesofEminentPhilosophers

Epic. Ep.Hdt. Epicurus, LettertoHerodotus

Epic. Ep.Men.Epicurus, LettertoMenoeceus

Epic. Ep.Pyth.Epicurus, LettertoPythocles

Epic. Nat. Epicurus, OnNature

Epic. Sent. Epicurus, VaticanSayings

Epict. Diss.Epictetus, Discourses

Epict. Ench.Epictetus, Handbook

Epiphanius, Adv.Haer. Epiphanius, AdversusHaereses

Eusebius, Praep.Ev. Eusebius, PraeparatioEnvangelica

Galen, Alim.fac. Galen, Dealimentorumfacultatibus

Galen, Caus.cont. Galen, DeCausisContentivus

Galen Caus.puls. Galen, DeCausisPulsuum

Galen, PHP

Galen, OntheDoctrinesofHippocratesandPlato

Galen, Plen. Galen, DePlenitudine

Galen, Syn.puls. Galen, SynopsisLibrorumSuorum,Sexdecim,dePulsibus

[Gal.] Def.med. [Galen], MedicalDefinitions

Gellius, NA AulusGellius, AtticNights

Hippolytus, Ref.HippolytusofRome, RefutationofAllHeresies

Josephus, Ant.Josephus, AntiquitiesoftheJews

Justin, Apol.Justin, Apology

Lucr.Lucretius, OntheNatureofThings

Marc.Aur.MarcusAurelius, Meditation

Nemesius, Nat.hom.Nemesius, OntheNatureofMan

Olymp. Phd. Olympiodorus, CommentaryonPlato’sPhaedo

Origen, Cels. Origen, AgainstCelsus

Origen, Evang.Ioannis Origen, CommentaryontheGospelofJohn Origen, Orat.Origen, DeOratione

Origen, Princ. Origen, DePrincipiis

Philo, Prob.PhiloofAlexandria, Quodomnisprobuslibersit

Philodemus, Ind. Stoic.Philodemus, IndexStoicorum

Philodemus, Ir. Philodemus, DeIra

Philodemus, Piet.Philodemus, DePietate

Philodemus, Sign. Philodemus, DeSignis

Plot., Enn.Plotinus, Enneads

Plut. Comm.Not. Plutarch, AgainsttheStoicsonCommonConceptions

Plut. Quaest.Conv. Plutarch, Quaestionesconvivales

Plut. Quomodoadul. Plutarch, Quomodoadulescenspoetasaudiredebeat

Plut. Soll.An. Plutarch, Desollertiaanimalium

Plut. Stoic.Rep.Plutarch, OnStoicSelf-Contradictions

[Plut.] Epit.[Plutarch], EpitomeoftheOpinionsofthePhilosophers [Plut.] Fat.[Plutarch], DeFato

Porph. Marc.Porphyry, LettertoMarcella

SE M SextusEmpiricus, AgainsttheMathematicians

SE PH SextusEmpiricus, OutlinesofPyrrhonism

Sen. Ben. Seneca, OnBenefits

Sen. Ep.Seneca, Letters

Sen. QNat.Seneca, NaturalQuestions

Sen. Vit.Beat. Seneca, OntheHappyLife

Simplicius, Cat.Simplicius, CommentaryonAristotle’sCategories

Simplicius, Ench. Simplicius, CommentaryontheEncheiridion

Stobaeus, Ecl.Stobaeus, Eclogues

Syrianus, Met. Syrianus, CommentaryonAristotle’sMetaphysics

Tacitus, Ann.Tacitus, Annals

Tatian, Ad.Gr. Tatian, OratioadGraecos

Tertullian, An.Tertullian, DeAnima

Tertullian, Apol.Tertullian, Apology

Introduction

Theclusterofproblemsaroundfreedom,determinism,andmoralresponsibilityis oneofthosethemesinphilosophythatarefascinatinginboththeircomplexity andtheirseeminglydirectrelevancetohumanlife.Historiansofideasoften assumethatinWesternphilosophythisclusterofproblemswasthesubjectof anongoingdiscoursefromantiquitytothepresentday.Thisis,however,an illusion.Muchofmyresearchonancienttheoriesofdeterminismandfreedomis devotedtoshowingthatwhatcommonlycountsasthisproblemclustertoday (oftenlabelledas ‘theproblemoffreewillanddeterminism’)isnoticeablydistinct fromtheissuesthattheancientsdiscussed atleastpriortothesecondcentury Itistruethatonemaincomponentoftheancientdiscussionconcernedthe questionofhowmoralaccountabilitycanbeconsistentlycombinedwithcertain causalfactorsthatimpacthumanbehaviour.However,itisnottruethatthe ancientproblemsinvolvedthequestionsofthecompatibilityofcausaldeterminismwitheitherourabilitytodootherwiseorahumanfacultyofafreewill. Instead,weencounterquestionsabouthumanautonomousagencyanditscompatibilitywithprecedingcauses,externalorinternal;withexternalimpediments; withdivinepredeterminationandtheologicalquestions;withphysicaltheories likeatomismandcontinuumtheory,andwithsciencesmoregenerally;with elementsthatdeterminecharacterdevelopmentfromchildhood natureand nurture;withepistemicfeaturessuchasignoranceofcircumstances;withnecessityandmodaltheoriesgenerally;withfolktheoriesoffatalism;andalsowith questionsofhowhumanautonomousagencyisrelatedtomoraldevelopment,to virtueandwisdom,toblameandpraise.Allthesequestionswerediscussed withoutreferencetofreedomtodootherwiseorafacultyofthewill atleastin ClassicalandHellenisticphilosophy.Thisvolumeofessaysconsidersallofthese questionstosomeextent.

Chapter1 followsupthequestionofwhenthephilosophicalproblemsofthe compatibilityofuniversalcausaldeterminismwithfreedomtodootherwiseand withfreewillemerged.Tothatend,IworkthroughanarrayofancientphilosophicalsourcesfromAristotletoAlexanderofAphrodisias,theearlythirdcentury PeripateticandcommentatoronAristotle.Istartwithanumberof philosophicaldistinctionsthatprovideasetoftoolsfortheenquiry(andthatare alsoexpedientforsomeofthelaterchaptersinthiscollection).Mostimportant arethedistinctionsbetween(i)indeterministfreedom(freedomtodootherwise, freedomofdecision,andfreedomofthewill);(ii)freedomfrompredetermination;

and(iii)freedomthatcancoexistwithfullcausaldetermination(freedomfrom externalcompulsion,fromexternalandinternalcausaldetermination).Isubsume underthenameofthe ‘free-willproblem’ thethreeproblemsofthecompatibility ofdeterminismwiththethreekindsofindeterministfreedom.

Theresultsoftheinvestigationaresignificant.Itturnsoutthatwhatisoften describedintermsofthe ‘discovery’ oftheproblemofcausaldeterminismand freedomofdecisioninGreekphilosophyinfactarisesfromanaccidentalcombinationandmixingupofAristotelianandStoicthoughtinlaterantiquity.More precisely,itappearsthatthefree-willproblemisinadvertentlyconceivedasthe resultofa(mis-)interpretationofAristotle’sphilosophyofdeliberatechoiceand action asheintroducesitinhisethics inthelightoftheearlyStoictheoryof determinismandmoralresponsibility.The(con-)fusionoriginateswiththe beginningsofAristotlescholarship,atthelatestintheearlysecondcentury , possiblyalittlebeforethat,andundergoesseveralmetamorphoses.Arangeof ideasareabsorbedatvariouspointsintothisdevelopment:fromthelateStoics, especiallyEpictetusandpossiblyMusonius;fromsomeanonymousMiddle Platonists;fromsomelaterPeripatetics;and,itseems,alsofromsomeearly Christianwriters.Eventually,thedevelopmentarrivesatafullnotionoffreedom ofdecisionandanexpositionofthe ‘free-willproblem’ inAlexanderof Aphrodisias’ OnFate andinthe Mantissa ascribedtohim.Thelatebirthofthe free-willproblemisthusdatedinthesecondcentury .

Chapter1providesaframeworkfortheremainderofthevolume,bothhistorically,bycoveringtheentiredevelopmentfromAristotletoAlexander,and conceptually,inthatitintroducesanumberofbasicnotionsthataremadeuse ofrepeatedlyinlaterchapters.

Therearesomepre-Aristoteliantextsthatconsidertherelationbetweenmoral accountability,ontheonehand,andnecessitation,fate,andexternalorinternal force,ontheother.Theseinclude prominently Gorgias’ EncomiumofHelen andvariouspassagesinPlato’soeuvre,inparticularinthe Republic.Noneofthese textsdisplaysanyawarenessofthecontemporaryproblemofcausal(event) determinismandfreedomtodootherwise,orevenofeitheroftheseconcepts. Formoralresponsibilityinthe Encomium,RachelBarney(Barney2016,§2)isa goodsourceofinformation.ForPlato,Hecht2014isuseful:Hechtcomestothe conclusion,explicitlystated,thatPlatodidnothaveanotionoffreedomtodo otherwise,andhearguesconvincinglythatPlato’sfreedomisfreedomfrom constraint(Hecht2014,204–6).Serioussustainedphilosophicaltheorybuilding andanalysisofsomeoftheproblemsofdeterminismandfreedomstartswith Aristotle(seeChapter1,section4).Aristotleisoftenconsideredtobethe first philosopherwhodiscussedthefree-willproblem.Inparticular,heisthoughtto connectfreewilltomoralresponsibilityinhis NicomacheanEthics and Eudemian Ethics.Threeessaysinthisvolumearededicatedtomoralresponsibilityandthe questionoffreewillinAristotle.

NicomacheanEthics Book3,chapters1–5(EN 3.1–5),hasbeenthetopicof innumerablepublicationsthatconnectthispartofthe Ethics withfreewill,since initAristotleconsidersthetopicsofresponsibility,choice,anddeterminationof character.Thequestionoftheoverallpurposeofthispartofthe Nicomachean Ethics is,however,generallyleftunresolved. Chapter2 providesananswertothis questionandindoingsoproducesaunifiedinterpretationof EN 3.1–5.This interpretationmakesitclearthatAristotle’stheoryofresponsibilityisnotbased onanotionoffreedecisionorfreewill,andthatthereisnonotionoffreewillin thetheoryatall.TheprimaryfocusofthechapterisanexpositionofAristotle’ s theoryofwhatmakesusresponsibleforouractionsandourcharacter.Inthis context,Iremarkattherelevantplacesonissuesoffreedom-to-do-otherwise,free choice,andfreewill,andhowtheyarewronglyattributedtoAristotle.Thechapter startswithsomepreliminaryobservationsaboutpraise,blame,andresponsibility. Itthensetsoutindetailhowallthekeynotionsof EN 3.1–5areinterrelated.In thiswaythecarefullystructuredcomplexityofAristotle’stheoryofaction,characterdevelopment,andmoralresponsibilitybecomesapparent.Thesettingoutof theseinterconnectionsmakesitthenpossibletoprovideacomprehensiveinterpretationofthepurposeofthepassage.Itemergesthatits primarypurpose isto explainhowagentsareresponsiblefortheiractionsnotjustinsofarastheseare actionsofthiskindorthat,butalsoinsofarastheyarenobleorbase:thisisthe stepfromresponsibilitygenerallyto moral responsibility.Agentsareresponsible fortheiractions qua nobleorbasebecause,typicallyviachoice,theircharacter dispositionsareacausalfactorofthoseactions.Thechapterillustratesthevarious differentwaysinwhichAristotlebelievesthatagentscanbecausesoftheiractions byreferencetohisfourbasictypesofagents:thevirtuous,thevicious,thestrongwilled,andtheweak-willed.Animportant secondpurpose of EN 3.1–5istoexplain howagentscanbeheldresponsibleforcertainconsequencesoftheiractions,in particularfortheircharacterdispositionsinsofarasthesearenobleorbase,thatis, virtuesorvices.Again,itisshownthatnonotionoffreewillisinvolvedin Aristotle’sexplanation.ThesetwopurposesarenottheonlyonesthatAristotle pursuesinthepassage.Theyare,however,thepurposesAristotlehimselfindicates inits firstsentenceandsummarizesinitslastparagraph,andthosethatgivethe passageasystematicunity.Aristotlethussetsthescenewiththediscussionof severalphilosophicalproblems:howmoralresponsibilityandexternalforcerelate toaction;howignoranceofcertainfactorsinactionaffectsmoralresponsibility; andwhateffectcharacterdeterminationbynatureandeducation(orthelack thereof)haveonmoralresponsibility.

Thereis,aboveall,onefamoussentenceinthe NicomacheanEthics Book3, chapter5,aboutthatwhichisinourpoweroruptous(eph’hēmin),thathas markedlyshapedscholarlyandpopularopinionalikewithregardtoAristotle’ s presumed theoryoffreewill,andwhichhasrepeatedlybeenusedtosupportthe assumptionthatAristotlediscussedfreechoiceorfreewill.Thisgoesagainstthe

grainofwhatIamconvincedtobethetruthaboutAristotleandancientClassical andHellenisticphilosophy.Soin Chapter3 ofthisvolume(whichfallsintothe categoryofmyworkthatIcall ‘settingthingsrightonceandforall Ihope’) Iofferanin-depthtextualanalysisofthatsentenceanditslinguisticcontext,with aviewtofreewillandfreechoice.Theresultisthatthereisnoacceptable interpretationinwhichthesentenceprovidesanyevidencethatAristotlediscussedfreedomofchoiceorfreedomofthewill.Mostassertionsthatitdoestend tobebasedonanoddmistranslationoftheGreek.Thusthesentencethatis sometimesadducedasthemainpieceofevidencefortheclaimthatAristotlewas anindeterministwithrespecttobothchoosing(prohairesis)andacting(praxeis, prattein)turnsouttobenoevidenceforthisclaimatall.

ThefairlywidespreadmistranslationnotedinChapter3,whichhasledgenerationsofphilosopherstoendorsetheincorrectviewthatthe NicomacheanEthics showsthatAristotlehadanotionoffreewilloranotionoffreechoice,ismost peculiar.ItspeculiarityhadmystifiedmesinceIwasteachingthe Nicomachean Ethics for ‘Finals’ (theClassics finalexamination)inOxfordintheearly1990s.Its stubbornrecurrenceeveninthelatetwentiethandearlytwenty-firstcenturies stronglysuggestedthattherehadtobemoretoitthanjustasimpleerror.So IdecidedtofollowthejourneyofthisonesentencefromwhenitleftAristotle’ s ‘ pen ’ tothepresenttime.Thisledto Chapter4 (whichfallsinthecategoryofmy workthatIcall ‘academicdetectivestories’).ItisacompanionessaytoChapter3 whichinvestigatestheconvolutedhistoryofthereceptionofAristotle’ s NicomacheanEthics 3.5,lines1113b7–8.Itbecomesapparentthatthissentence hasnotonlymarkedlyshapedscholarlyandgeneralopinionalikewithregardto Aristotle’stheoryoffreewill,butithasalsotakenonacuriouslifeofitsown.The short firstpartoftheessayexaminesthetwolinesandtheirimmediatecontext, thistimewithafocusonthetextanditsmeaningratherthanthephilosophical questionsitraises.(Thereis,nonetheless,someunavoidableoverlapinthis first partwithChapter3.)¹Themuchmoreextensivesecondpartofthechapter exploresthereceptionofthesentence.Thisincludesitspresenceinpresent-day popularculture,partiallyforentertainmentbutalsobecauseitisasymptomof how,intheeraof ‘virtualwisdom’ andsocialmedia,aphilosophicallysignificant blunder,onceithasgainedafoothold,isalmostimpossibletoreverseinthe commonconsciousness.Moreseriously,theinvestigationfollowsanumberof unforeseenandexhilaratingtwistsandturnsalongtheroutefromAristotletothe contemporaryengagementwithancientphilosophyvialaterancient,Byzantine, Arabic,LatinMedieval,Renaissance,andVictorianscholarship.Theerroris revealedtobetheresultofamismatchintextualtransmission atthemeeting pointofLatin,Arabic,andGreekmanuscripts betweenAristotle’stextanda

¹ItisMelissaLanetowhomIowetheinsightthatwhatIpresentedasonepaperatPrincetonin 2014wereactuallytwopapers,companionstoeachother,butbestdividedbytheirseparatepurposes.

commentaryonthattext.Onceinexistence,thiserrorinfluencedtheunderstanding ofAristotle’sviewonfreewillbyleadingtoreinterpretationsofthe faulty textual readingfromanineteenth-centuryperspectiveandintheprocessimbuingitwitha gooddoseofChristiandogma.Andforreasonsthatthereaderislefttopuzzleout forthemselves,eveninthescholarlyexactingandphilosophicallyunforgiving climateofanalyticancientphilosophy,theerrorliveson.

Chapters5to9aredevotedtoissuesofdeterminism,freedom,andmoral philosophyin Hellenisticphilosophy.Oneofthemainobstaclesanyscholarof thatperiodencountersisthelackofsurvivingsources.(Thereadershouldnotkid themselvesaboutAristotleinthisrespect,though.Onlyabouta fifthofhiswork survives,andagoodbitofthisnotfullyworkedout.)Wehaveonlyasmall percentageofwhattheEpicureansandStoicswrote,andmostofthatinsecondary,tertiary,orquaternarysources,includingmanythateitherlackthebackgroundforunderstandingtheoriginaltextsorhaveanintentiontodistortthemor takethemoutofcontext,soastobebetterabletocriticizethem.Thispresentsa numberofmethodologicalchallenges.

ThenextphilosopherafterAristotlewhohasbeencreditedwitheitherdiscoveringorintroducingthefree-willproblemis Epicurus.Wearefortunateto haveasummaryofhisphilosophicaltheoryinhislettersto Menoeceus, Pythocles, and Herodotus,andinLucretius’ poem OnNature .However,mostofEpicurus’ worksarelost,anexceptionbeingthePapyruswithBook25ofhis OnNature, whichishighlyrelevanttothetopicsofthisvolumebutinmanyplacesimpenetrable,largelybecauseitisinsuchlacunoseform.

Epicurusandhisfollowersareatomistsand,asaresult,theEpicureantheory anddiscussionofissuesofdeterminism,freedom,causation,andmoralresponsibilityareallgroundedinEpicurus’ atomism,includinghisintroductionofthe notoriousswerves.Chapters5and6inthisvolumearedevotedtoEpicurusand theEpicureans.

Chapter5 discussesmoralresponsibilityandmoraldevelopment,leavingfor Chapter6questionsoftheroleoftheswerveinEpicureandiscussionoffreedom anddeterminism.TherelianceofEpicurus’ doctrineonatomismrequireshimto providedetailedexplanationsofhowcausation,freedom,moraldevelopment, moralresponsibility,andtheirrelationstophysicsandethicsaretobeunderstood atthemicrolevelintermsofatoms.Theresultisinmanyrespectsasurprisingly moderntheoryofhumanpsychologicalandmoraldevelopment.Itiscombined withanequallyfascinatingforward-lookingnotionofresponsibility,whichisnot concernedwithpraisingorblamingindividualsforpastactions,butlaysthe groundsonwhicheveryoneistousethepastandpresentinordertoimprove theirfuturebehaviour.Thistheoryhasmuchtotelltocontemporaryphilosophers andmoralpsychologists.Itrejectsthewell-troddenbackwards-lookingperspectiveofmoralresponsibilityonnon-virtuouspastbehaviourasabasisforjustified blameandpunishment:initsplaceitputsafreshfuture-orientatedperspectivein

whichthefactthatadulthumanbeingsaremorallyresponsibleagentsisfocused onprimarilyasabasisforfutureself-improvementofourselvesandothers.

ThereissufficientevidencetoshowthatEpicurushadanotionofmoral responsibilityforactionsthatisbasedontheagent’scausalresponsibility,as opposedtotheagent’sabilitytoactorchooseotherwise.Heconsideredita necessaryconditionforpraisingorblaminganagentforanactionthatitwas theagentandnotsomethingelsethatbroughttheactionabout.Asaresult,the centralquestionofmoralresponsibilityiswhethertheagentwasthe,ora,causeof theaction,orwhethertheagentwasforcedtoactbysomethingelse.Themain factorsfor ‘somethingelse’ thatEpicurusconsidersarewhatwewouldcallnature (one’shereditarymake-up)andnurture(upbringingandteaching).Epicurus holdstheviewthatactionscanbeattributedtoagentsfromthepointonwards whenitisintheiractionsthattheagent, qua moralbeing,manifeststhemselfasa rationalbeingthathasbeliefsthatgobeyondtheir(unquestioned)hereditaryand environmentallyinducedbeliefs.

Asaresult,unlikeintheoriesthattiemoralresponsibilitytotheabilityto dootherwise,thequestionofmoraldevelopmentbecomesall-important. Consequently,thechaptercollectsanddiscussestheevidenceforEpicurus’ viewsonmoraldevelopment,askingthequestionsof(i)howhumansbecome moralbeingsand(ii)howhumanscanbecomebetterpersons.Epicurusenvisaged acomplexwebofhereditaryandenvironmentalfactorsasshapingthemoral aspectofahumanbeing.Itappearsthatheexplainedthisdevelopmentbothatthe macrolevelofhumanbehaviourandindetailwithhistheoryofatoms.Of particularinterestarehisviewsconcerninghow,atomically,weacquirebeliefs andhowwecanchangeourbeliefs,inparticularhowwecanreplacefalsebeliefs withtrueones.Thisatomic-levelexplanationshedsimportantlightonEpicurean ethics,boththeimportanceitplacesonteachingandtheimportanceitplaceson lifelonglearningandontheuseofrepetitiveexercisesforlearning.Onesignificant resultisthatEpicureanethicsdoesnothavethefunctionofdevelopingor justifyingamoralsystemthatallowsfortheeffectiveallocationofpraiseand blame.Ratherthefunctionofethicsistogiveeveryoneachancetomorally improve.

ThemostfrequentlydiscussedEpicureanissueregardinghumanfreedomis thatoftheroleplayedbytheswervesintheirtheory.Thereisno first-hand testimonyfromEpicurusonthispoint.Swervesareatomicminimalrandom motions.ThereissufficientindirectevidencethatEpicurusintroducedthe swerves,amongotherthings,asanecessaryconditionfortheexistenceoffree volitions.Beyondthat,thefunctionoftheswervesforfreedomissomethingofa mystery.Onthefaceofit,theintroductionofrandommotionsinordertosecure thefreedomofhumanvolitionsseemsdubiousratherthanenlightening.Ifthe motionsarerandom,howcanthevolitionsbetheagent’svolitions?Amultitude ofsuggestionshavebeenofferedastohowexactlytheswervescouldaccomplish

this.Whenthisessaywaswritten,thereweretwomaincamps:theprevalent viewpointrequiredatleastoneswerveineveryfreevolition,usuallytowarrant thattheagenthastwo-sidedfreedom(Chapter1,section2);theothercamp requiredatleastoneswerveinthedevelopmentofhumanagentsthatmakes themagentswhosevolitionsareneitherinternallynorexternallyforced.These factionsareroughlyalignedwiththeviewsthatEpicurus’ notionoffreeaction requiredafacultyoftwo-sidedfreedomandthatEpicurus’ notionoffreeaction requiredautonomousrationalagents. Chapter6 aimstosettleforgoodatleast someofthequestionsregardingtheroleoftheswervesandEpicurus’ notionof freedom.Thechaptertracesthreeinterlockingquestions:(i)DidEpicurusdeal withthekindoffree-willproblemwithwhichheistraditionallyassociated,i.e.did hediscussfreechoiceormoralresponsibilitygroundedonfreechoice?(ii)Tosave suchfreechoice,didEpicurusstipulatethattheswerveswereinvolvedinindividualdecisionprocesses?(iii)Ifnotfreechoice,whatthenwastheproblemthat theswervesweremeanttosolve?Thereisnodirectevidenceforapositiveanswer to(i)or(ii).Rather,theevidencesuggeststhat,forEpicurus,actionsarefully determinedbytheagent’smentaldispositionattheoutsetoftheiraction,andthat Epicureanmoralresponsibilitypresupposesnotfreechoicebutthatapersonis unforcedandcausallyresponsiblefortheiraction.Regarding(iii),thismeansthat onthebasisoftheseresultsandthepassagethatconnectstheswervestofree volition,itbecomesplausiblethatEpicurus’ problemwasthis:howcanhuman agencybenon-necessaryinanatomisticallyexplainedordereduniverse? Thecontextofhisargumentisprovidedbyotheratomistictheories.Itappears thatEpicurus’ swerveswereintendedtoexplainthenon-necessityofagency withoutunderminingEpicurus’ atomisticexplanationoftheorderinthe universe,andthattheydidsobymakingthementaldispositionsofadultsnonnecessary.Twoalternativeconjecturesareofferedtoaccountforhowtheswerves couldhaveachievedthis.Epicurusalsoseemstohaveconnectedlogicwith determinismandarguedthatalogicalprinciplesimilartoasemanticversionof theLawofExcludedMiddle,ifaccepted,wouldleadtothenecessityandfatedness ofallevents,andthatthereforeitshouldberejected.ThisisdiscussedinBobzien 1998,75–86.²

Thelastthreechaptersaregivenoverto theStoics.The firstconcernsfreedom andresponsibility,thesecondteleologyandcausation,andthelastisadetailed studyofthetheoryofcausesadvancedbyChrysippus,thirdheadoftheStoa,who refinedandelaboratedtheearlyStoictheoryofdeterminismanddefendedit againstobjectionsbyotherschools.

Chapter7 providesanintroductiontotheStoictheoriesoffreedomand whatisuptousfromthebeginningtotheendofStoicphilosophyinantiquity.

²OnthistopicseenowalsoBown2016.

Itinvestigateshow,fromtheearlyStoicsviaEpictetustothelateStoicsofthe secondcentury ,freedomandresponsibilityareconnectedinStoicphilosophy withethics.Inthiscontext,themostimportantdistinctionisthatbetween theStoicnotionofthatwhichdependsonus(eph’hēmin)andtheirnotionof freedom(eleutheria).Thatwhichdependsonusisalwaysconnectedwithhuman actionandintentioninStoicphilosophy,andislocatedwithinthesphereof Stoicpsychology.Foreveryhumanbeing,therearethingsthatareuptothem. Freedom,bycontrast,isanotionthatoriginatesfrompoliticaltheory,iscontrastedwithslavery,andis,fromthere,thenintroducedinto Stoicethics.Forthe Stoics,freedomisacharacterdisposition morespeci ficallyavirtue andthus canbeattributedonlytowisepeople.Theconfusionofthesetwoquitedistinct conceptsandtheirrolesinStoicphilosophyhaswreakedmuchhavocin twentieth-centuryliteratureonStoicfreedom(whichtheessayuntanglesand invalidatesintheprocess).

Thechaptertracestherelationsbetweenthatwhichdependsonus,freedom, andethicsthroughthreestagesofStoicphilosophy.(i)FortheearlyStoics,that whichdependsonusisnotaphilosophicaltermbutisusedasanaturallanguage expressionwhichdenotesourbehaviour,includingouractionsandourrefrainingsfromaction,aswellasourassentandintentionthatleadtotheactions. Freedom(eleutheria)isonlymentionedinthecontextofpoliticsandethics,and rarelysoeventhere.Itappearstohavereferredtoavirtuousperson’spowertodo whattheywanttodo,whichisthesameaswhattheyshoulddo.Nosource connectsthetwonotions.(ii)ForEpictetus,bothfreedomandthatwhichdepends onusarenotionsthatarecentraltohisphilosophy.Wewitnessachangeoffocus fromthatwhichdependsonus(toeph’hēmin)tothethingsthatdependonus(ta eph’hēmin);therangeofthesethingsismorerestricted,comprisingourassent, intention,andrefrainingfromaction.Unlikeactions,thesethreeareinternalto agents.Epictetusdiscussesthethingsthatdependonusmainlyinthecontextof analreadyestablishedmoraltheory.Epictetus’ notionoffreedomissimilartothat oftheearlyStoics,butittypicallyappearsincompanywithagroupofterms connectedwithtranquillityofthemind.Importantly,inhisethicsEpictetus connectsthethingsthatareuptousandfreedom,somethingnotknownforthe earlyStoics.Thediscussionhasprogressedtoanemphasisoninternalacts(assent, intention)andhasbeenmovedtoethics.Thisnotwithstanding,Epictetus’ theory seems,unsurprisingly,tobefullycompatiblewithearlyStoicdeterminism.(iii)In thesecondcentury thedebateshiftsfurther.ThelateStoicsarefacedwith MiddlePlatonistsandsomePeripateticsproposingroughlylibertariantwo-sided notionsofwhatisuptousthatcorrodetheearlierdiscrepancybetweenwhatisup tousandfreedom.Adaptingtothenewsituation,thelateStoicsdevelopednew arguments,adjustedtothenewdebate,anddefendedtheirowntheoryassuperior. ThislateStoictheoryisstillinallmajorpointscompatiblewithearlyStoic determinism.

Chapter7complementsChapter1inseveralways.Ratherthanfocusingonthe developmentofthefree-willproblem,ittracesthedevelopmentoftheassociated debatesinwhichtheancientStoicswereinvolvedthroughthecenturies,showing howtopicsandinterestsshiftedand,relatedly,howtheconceptualframework withinwhichtheStoicselaboratedanddefendedtheirtheoriesaltered.

AsEpicureantheoryoffreedomandresponsibilityisdeeplyinfluencedbyand basedontheirphysics,sotooisStoictheory.WhiletheEpicureansareatomists, theStoicsarecontinuumtheorists.Therearenosmallestpartsofmatter,place,or time,andwhateverhappensiscausedbyefficientcausesthatatleastpartially coexistwiththeireffect.WheretheEpicureanshavegodswhoareexternaltothe worldandwhodonotcareabouthumanaffairs,theStoicshaveadivinitythatis immanenttotheuniverseandthatgovernseveryelementofwhathappensinit past,present,andfuture.Asaconsequence,thedistinctivefeatureofearlyStoic determinismisitscombinationofteleologicalandapparentlymechanicalelements.Morebroadly,thequestiontheyfaceishowtocombinetheologyandscience. Chapter8 pursuestheessentialquestionofhowteleologicalelementsandefficient causationweremergedinStoicdeterminism.Attheverybeginningoftheir school,theStoicsdonotpresenttheirdeterminismascausaldeterminism,that is,intermsofuniversalefficientcausation.Rather,itisintroducedinStoic cosmologywithastrongteleologicalelementinthecontextofatheoryofnatural motions.Itisatheorybuiltonafundamentaldistinctionbetweenaglobalandan inner-worldlyor ‘local’ perspectiveonevents,inwhichoneactiveprinciple, variouslycalledNature(phusis),Cause(Aitia),andReason(logos),istheglobal principlethatdeterminesallinner-worldly ‘local’ events.Yet,inordertoexplain hisdeterminism,Chrysippusalsoemployedhisconceptionofefficientcausalityas thatwhichconnectsinner-worldlycausesandtheireffects.Itcanbeshownthathe maintainedauniversalcausaldeterminisminthemodernsenseoftheterm,if presentedinaslightlydifferentway,usingcounterfactualrelationsratherthan causallaws.TheStoicnotionsofefficientcausesascorporealandresponsiblefor bothsustenanceandchange,andofeffectsasincorporealandpredicates,are indispensableforafullunderstandingofthistheory.TheteleologicalandseeminglymechanicalelementsofearlyStoicdeterminismwerebroughttogetherin Chrysippus’ conceptionoffate(heimarmen ē).ItisherethatChrysippusplaces elementsofrationalityineverycause.(Thenotionoffateobtaineditspivotalrole inancienttheoriesofdeterminismandfreedomonlyasaresponsetotheStoic theory.)Inoursurvivingtexts,theexactworkingsofthisplacementofteleological elementsintoapparentlymechanicalcausesarepresentedbymeansofbiological andpsychologicalanalogies,amethodoftenemployedbytheearlyStoics.The chapterpursuestheseanalogiesandmakessuggestionsabouthowtheymight translateintoStoiccosmology.ItemergesthattheStoictheoryofNatureasworld seedandtheirtheoryofNatureasworldsoulandrationalagent,whichis contrastedwiththeindividualseeds,souls,andagentswithinNature,offera

fascinatingsolutiontothequestionofhowscienceandtheology,inparticularthe issueofdivinepredetermination,canbecombinedconsistentlywithinonetheory oftheworld.IntheearlyStoicview,wedonotfaceachoicebetweentheological explanationandscientificexplanationoftheworld.Rather,thesearetwocomplementaryexplanationsofthesamething.

Thelastchapter, Chapter9,isacompanionpiecetoChapter6ofmybook DeterminismandFreedominStoicPhilosophy (Bobzien1998),anditcanberead inconjunctionwithit,togoodeffect.Butitalsostandsonitsown.Bothchapters areconcernedwiththeinterpretationofalongandfamouspassageinCicero’ s DeFato onChrysippus’ defenceofthecompatibilityoffateintheformsofcausal determinismandmoralresponsibility.Thechapterin DeterminismandFreedom investigateshowthepassage,andespeciallythecylinderanalogy,increasesour understandingofStoiccompatibilism,describesthespeci ficproblemofmoral responsibilityanddeterminismthatChrysippusandhisopponentsencountered, andshowshowitdiffersfromproblemsthataretodaysubsumedunderlabels suchas ‘thefree-willproblem’.Chapter9ofthepresentvolumehasasitsmain purposethelayingtorestofarecalcitrantmisconstructionofadistinction betweentwokindsofcauses(auxiliarycausesandprincipalcauses)that Chrysippusintroducesinthecontextofdefendinghisview.(Anotheressayin thecategoryofmyworkthatIcall ‘settingthingsrightonceandforall Ihope’.) Thismisinterpretationtakesthetwotypesofcausestobecooperatinginone instanceofcausation.However,painstakingtextualanalysis,togetherwiththeuse ofsomeparallelpassages,makesitclearthatChrysippus’ distinctionisinsteadone ofthecharacteristicsofefficient antecedent causesandissituatedinthecontextof adebateaboutthepredeterminationofhumanaction,possiblyamongother things.Inprinciple,suchantecedentcausescouldbethoughtofasprincipaland self-suf ficientcausesthatnecessitatetheireffect.ThisishowChrysippus’ opponentsinthedebatecharacterizedthemintheirargumentagainsttheStoictheoryof fate.Alternatively,antecedentcausescanbethoughtofasauxiliarycausesthat startortriggeraninstanceofcausationandthat,inordertoproducetheeffect, mustcooperatewithanothercause,namelytheobjectatwhichtheeffectoccurs. Inthiscase,theantecedentcausesareneithermaincausesoftheeffectnordothey necessitatetheeffect,sincewhethertheeffectoccursorwhateffectoccursdepends cruciallyonthepropertiesoftheobjectatwhichitoccurs,whichfunctionsasthe secondandmoresubstantialcauseoftheeffect.ThisalternativeisChrysippus’ view,andthechaptershowsthatthepointofChrysippus’ distinctionofthetwo typesofcausesistomarkitoutagainsthisopponents’ assumptionthatthe antecedentcauseisthesolecauseoftheeffectandnecessitatesit.Thus Chrysippusdoesnotassumethatcausesofthe firsttypeexistwithintheworld, anditseemsthatsuchcausesplayednoroleinStoictheoryofefficientcausation. Theabove-mentionedrecalcitrantmisinterpretationofthetextcanthusbelaidto rest.Thechapterpursuesasecondpurpose,whichistosetoutandsystematizethe

evidencewehaveforanearlyStoic,andinparticularChrysippean,theoryof causes.Themostfundamentaldistinctionofcausesisthatbetweencausesof changeandcausesofstates.Theactiveprincipleor pneuma inanobjectisthe causeofitspresentproperties,andinthissensethecauseofthestateitisinandof itsfunction.Anotherdistinctionisthatbetweencauseswhosepresenceatleast partiallyprecedesthatoftheireffects,andcausesthatareconcurrentwiththeir effects.Wherethereisanantecedentcause,therealwaysseemstobecooperation ofthesetwokinds.Theoverallresultsofthechapterdonotgreatlyaffectthe interpretationofChrysippus’ cylinderandconeanalogyfordeterminismand freedom(forwhichseeBobzien1998,chapter6).Rather,theyprovideamore stableandmoreconsistentbasefromwhichtounderstandtheanalogy,which tallieswithwhatelseweknowaboutChrysippus’ theoryofcausationand,more widely,withhiscosmologyandphysics.Italsonicelysupportswhatweknow aboutChrysippus’ theoryofcausaldeterminismandfatefromothersources.

AsChapter1illustrates,thedevelopmentoftheoriesondeterminism,freedom, andmoralresponsibilitydoesnotendwiththeStoics,orevenwiththeStoics discussedinChapters1and7.Thus,Senecahashisownviewontheissues,similar to,butfarfromidenticalwith,thoseoftheotherStoicsherediscussed.Avaluable recentoverviewofSeneca’spositionandhowitrelatestoearlierStoicscanbe foundinJulaWildberger’sextensivestudy(Wildberger2006).Fortheearly commentatorsonthe NicomacheanEthics,thereexistsnowavolumeeditedby AntoninaAlbertiandBobSharples,whichmuchimprovesourunderstandingof thesecommentaries(AlbertiandSharples1998).The fifthchapter,byAlberti herself,treatsthetopicsofthevoluntaryandofchoice.Thedevelopmentofthe notionsofthewillandoffreewillinlaterantiquityissetoutinMichaelFrede’ s posthumouslypublishedSatherLectures(Frede2011).Fredebroadlyagreeswith thephilosophico-historicalinterpretationputforwardinthe firstessayofthis volume,inparticularwiththeabsenceofawillinAristotleandtheearlyStoics,the emphasisonfreedomasamoralqualityinEpictetus,andthePlatonistand PeripateticresponsestotheStoictheoryoffreewillanditscompatibilitywith divineprovidenceandcausaldeterminism,aswellasthefactthatAlexanderof Aphrodisiaswasthe firsttoadoptanotionoffreewillastheabilitytochooseto actornottoact,givenidenticalcircumstances(inhischapters2–6).AsIwrite elsewhere, ‘TheachievementofthesechaptersliesinthewayFredecarefullyjoins themtogetherandusesthemasabasisforsomesubstantivecriticismand rewritingofthehistoryoffree-willregardinglateantiquePaganandChristian authors,inparticularPlotinus,OrigenandAugustine ’,and ‘[Frede’s]Chapter7 tracesearlyChristiannotionsofawill,withemphasisonOrigen,whoseview FredearguestobeatbaseEpictetan,and,whereitdiffersfromtheStoics,torely onPlatonistelements.Chapter8contendsthatPlotinus’ theoriesofgodandfreewillwerenotbasedonJudaeo-Christianthought,butratherstronglyimpactedby Stoicphilosophy,withsomePlatonistelements.Chapter9arguesthatAugustine’ s

notionoffree-willisbasedonlaterStoictheorytoanevengreaterdegreethan thoseofOrigenandtheearlyapologists.’³Sothissmallbutimportantbook providesawelcomeandeasilyaccessiblesequeltothepresentvolume.

Itistheseparabilityofanincorporealsoulfromthebodythatbringsthe theoriesanddebatesonfreedomtoanewlevel.Aristotle’shylomorphismand EpicureanandStoicmaterialismdonotpermitahumansoultosurvivethe destructionordemiseofthehumanbody.ThisisnotsowithPlatonistand Christianphilosophy.Here,UrsulaCoope’sexcellentrecentstudyonfreedom andresponsibilityinNeoplatonistphilosophyprovidesbothoverviewandindepthanalysis(Coope2020).IttiesinNeoplatonismwiththePre-Plotinian historicaldevelopment,includinginparticularPlatoandtheMiddlePlatonists. Itprovidesalearnedphilosophicalstudyofthevariouselementsoffreedomand responsibility,introducingthereadertothespeci ficallyNeoplatonistnotionsof self-determination,self-constitution,self-making,andself-reflexivitythatmove thediscussionsanddebatestonewlevels,fromPlotinus,viaPorphyryand Iamblichus,toProclus,Damascius,andSimplicius.Letme finallyalsomention tworecentmulti-authoredcollectionsofpapersonfreedom,determinism,causality,andmoralresponsibility Destrée,Salles,andDeZingano2014andMasi andMaso2013 thetopicsofthecontributionsinwhichrangefromDemocritus toSimplicius.Asshouldthushavebecomeclear,theessaysinthepresentvolume introduceandexamineonlyasmallpartoftherichtroveofancientthoughtsand theories aswellastheirhistoricaldevelopments onquestionsofdeterminism, freedom,andmoralresponsibility. ³Bobzien2012.