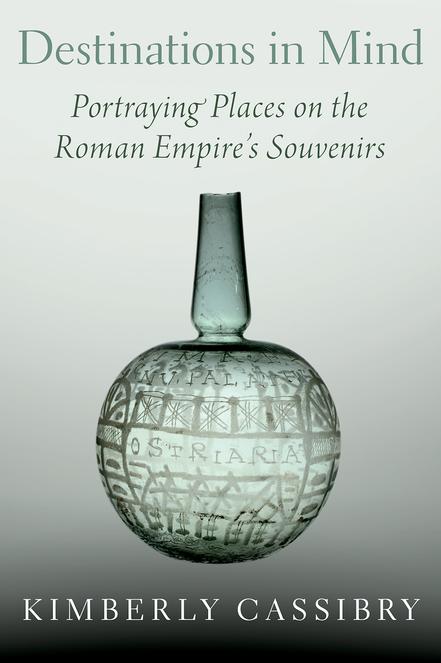

Destinations in Mind

Portraying Places on the Roman Empire’s Souvenirs

KIMBERLY CASSIBRY

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cassibry, Kimberly, author.

Title: Destinations in mind : portraying places on the Roman Empire’s souvenirs / Kimberly Cassibry. Other titles: Portraying places on the Roman Empire’s souvenirs Description: New York : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2020055654 (print) | LCCN 2020055655 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190921897 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190921910 (epub) | ISBN 9780190921927

Subjects: LCSH: Rome—Antiquities. | Souvenirs (Keepsakes)—Rome—History. | Rome—In art. | Material culture—Rome—History. | Social archaeology—Rome. Classification: LCC DG77 .C35 2021 (print) | LCC DG77 (ebook) | DDC 937—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020055654

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020055655

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190921897.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

For my mother

List of Figures ix

Preface and Acknowledgments xv

Abbreviations xvii

Introduction: En Route to the Roman Empire 1

PLACES IN A GLOBAL EMPIRE 3

MATERIAL CULTURE AND MULTI-SENSORY EXPERIENCE 11

DESTINATIONS IN MIND: A USER’S GUIDE 13

1. On the Road: From Gades to Rome on the Itinerary Cups 17

THE ITINERARY CUPS AS ARTIFACTS 21

SETTINGS FOR TRAVELERS: ROMAN ROADS 35

SILVER CUPS WITH ITINERARIES 44

WORD MAPS 46

WORDS (ALMOST) BEREFT OF IMAGES 55

ITINERANT PATRONS: WHO WAS ON THE ROAD? 57

CONCLUSION 61

2. At the Games: Charioteers and Gladiators on the Spectacle Cups 63

THE SPECTACLE CUPS AS ARTIFACTS 65

SETTINGS FOR CHARIOTEERS AND GLADIATORS 76

GLASS CUPS WITH SPORTS STORIES 88

WORD GAMES 91

IMAGES IN VIRTUAL REALITY 99

PROVINCIAL PURCHASES 105

CONCLUSION 109

3. Along the Border: Hadrian’s Wall on the Fort Pans 111

THE FORT PANS AS ARTIFACTS 113

A SETTING FOR SOLDIERS: HADRIAN’S WALL 120

ENAMELING THE FORT PANS 124

LETTERS, LANGUAGES, AND LITERACY 126

MESMERIZING MOTIFS, PAST AND PRESENT 130

TO WHOM DID HADRIAN’S WALL MATTER? 142

CONCLUSION 143

4. By the Sea: Baiae and Puteoli on the Bay Bottles 146

THE BAY BOTTLES AS ARTIFACTS 148

SETTINGS FOR REVELRY AND COMMERCE 166

GLASSWARE ON THE MARKET 177

LABELS FOR BUILDINGS AND WISHES FOR READERS 181

BUILDING STORIES 185

THE BAY BOTTLES ABROAD 197

CONCLUSION 206

Conclusion: Not All Roads Lead to Rome 207

THEMATIC CONNECTIONS 207

ART HISTORY AND MATERIAL CULTURE 212 WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? 216

Notes 219 Bibliography 255 Index 273

FIGURES

Figure 1.1. Map of key sites mentioned in the book. 18

Figure 1.2. View of Itinerary Cups 1 to 4. 19

Figure 1.3. Itinerary of Cup 1. 22

Figure 1.4. Itinerary of Cup 2. 23

Figure 1.5. Itinerary of Cup 3. 24

Figure 1.6. Itinerary of Cup 4. 25

Figure 1.7a–d. Four views of Itinerary Cup 1. 26

Figure 1.8. Drawing of Itinerary Cup 1. 27

Figure 1.9a–d. Four views of Itinerary Cup 2. 28

Figure 1.10. Drawing of Itinerary Cup 2. 29

Figure 1.11a–d. Four views of Itinerary Cup 3. 30

Figure 1.12. Drawing of Itinerary Cup 3. 31

Figure 1.13a–d. Four views of Itinerary Cup 4. 32

Figure 1.14. Drawing of Itinerary Cup 4. 33

Figure 1.15. View of the road leading to the hilltop settlement at Ambrussum, France. 37

Figure 1.16. View of the remains of the Roman bridge, now called the Pont Ambroix, at Ambrussum, France. 37

Figure 1.17. Milestone marking mile 26 on a road north of Seville, Spain. 38

Figure 1.18. View of the amphitheater at Tarragona, Spain. 39

Figure 1.19. View of the Mausoleum of the Julii and arch monument at Glanum, France. 40

Figure 1.20. View of the bridge erected by Augustus and Tiberius at Rimini, Italy. 41

Figure 1.21. View of the arch monument for Augustus at Rimini, Italy. 41

Figure 1.22. View of the Porta Augusta at Nîmes, France. 42

Figure 1.23. View of the amphitheater at Nîmes, France. 43

Figure 1.24. Cups (from Boscoreale, Italy) with skeletons and the words of Greek sages. 46

Figure 1.25. Drawing of a fragment from the itinerary monument at Autun, France. 48

Figure 1.26. View of the itinerary monument at Tongeren, Belgium. 49

Figure 1.27. View of the arch monument that Marcus Julius Cottius set up in honor of Augustus at Susa, Italy. 50

Figure 1.28. Reverse of a Hadrianic aureus depicting Hercules Gaditanus. 52

Figure 1.29. View of the theater at Cádiz, Spain. 53

Figure 1.30. View of Glanum’s main street with the Alpilles mountains in the background. 53

Figure 1.31. Metal vessels recovered from the spring at Vicarello, Italy. 60

Figure 2.1. Drawings of the best-preserved Circus Cups: a) Colchester Cup, b) Couvin Cup, c) Mainz Cup, and d) the Trouville Cup, with losses restored from the Schönecken Cup. 66

Figure 2.2. Two views of the Colchester Cup. 67

Figure 2.3. Six views of the Couvin Cup. 68

Figure 2.4. Three views of the restored Mainz Cup. 69

Figure 2.5. View of the Schönecken Cup. 70

Figure 2.6. View of the Trouville Cup. 70

Figure 2.7. Drawings of the best-preserved Gladiatorial Cups: a) the Chavagnes Cup and b) the Montagnole Cup. 71

Figure 2.8. View of the Montagnole Cup. 72

Figure 2.9. Direct and oblique views of the Sopron Jar and Chavagnes Cup. 73

Figure 2.10. View of the Rome Jar. 74

Figure 2.11. Modern three-part mold used to produce historical replicas of the Montagnole Cup. 75

Figure 2.12. Oblique views of the Mainz Cup and the Chavagnes Cup. 76

Figure 2.13. Terracotta plaque representing a charioteer and a scout on horseback. 77

Figure 2.14. Terracotta plaque representing a wrecked chariot. 78

Figure 2.15. Mosaic (from Lyon, France) showing a chariot race in a circus. 79

Figure 2.16. View of the Circus Maximus, Rome, Italy. 79

Figure 2.17. Model of ancient Rome, with a focus on the Circus Maximus. 80

Figure 2.18. View of the obelisk previously in the Circus Maximus, now in the Piazza del Popolo, Rome, Italy. 81

Figure 2.19. Lamp representing a chariot race. 82

Figure 2.20. Silver cup (from Pompeii, Italy) representing a chariot race between cupids and psyches. 83

Figure 2.21. Lamp representing gladiatorial combat. 85

Figure 2.22. Lamp representing gladiatorial weaponry. 86

Figure 2.23. Oblique view of a mold-blown glass cup signed by Ennion. 90

Figure 2.24. Oblique views of two mold-blown glass cups with Greek phrases. 90

Figure 2.25. View of a mold-blown glass cup showing Neptune on a statue base. 91

Figure 2.26. Drawing of a graffito (from Pompeii, Italy) representing a gladiatorial match. 96

Figure 2.27. View of a fragmentary mold-blown cup (from Lyon, France) depicting gladiatorial combat. 98

Figure 2.28. Casts of relief sculptures (from Rome, Italy) showing discrepant scale of figures and setting. 100

Figure 2.29. Oblique views of the Chavagnes Cup and Rod. 104

Figure 2.30. Oblique views of the Montagnole Cup. 105

Figure 2.31. View of the early amphitheater at Lyon, France. 106

Figure 3.1. View of the Rudge Cup. 114

Figure 3.2. View of the Amiens Patera. 114

Figure 3.3. View of the Ilam Pan. 115

Figure 3.4. View of the Hildburgh Fragment. 117

Figure 3.5. View of the Bath Patera. 117

Figure 3.6. View of the Basildon Fragment. 118

Figure 3.7. Drawing of the Beadlam Pan. 119

Figure 3.8. Map of Hadrian’s Wall. 121

Figure 3.9. Remains of Hadrian’s Wall between the River Tyne and Chesters, England. 122

Figure 3.10. Funerary monument for Regina (from South Shields, England) with inscriptions in Latin and Palmyrene. 123

Figure 3.11. The Battersea Shield from the River Thames, England. 131

Figure 3.12. Dragonesque brooch with enameling, England. 132

Figure 3.13. Helmet with triskels, Amfreville, France. 133

Figure 3.14. Fob with triskel, Wales. 134

Figure 3.15. Disk brooch with triskel and preserved enamel, Wales. 135

Figure 3.16. The Crowle Pan with triskels and traces of enamel. 135

Figure 3.17. The Winterton Pan with checkerboard pattern and preserved enamel. 137

Figure 3.18. The Eastrington Pan with checkerboard pattern, handle, and preserved enamel. 138

Figure 3.19. View of a floor mosaic with turreted wall motif, Fishbourne Palace, England. 139

Figure 3.20. Monument for Brigantia (from Birrens, Scotland) shown with a mural crown. 140

Figure 3.21. Side view of the funerary monument for Quintus Sulpicius Celsus, with a mural crown, Rome, Italy. 141

Figure 3.22. View of the Ribchester Helmet, with a mural diadem across the forehead. 142

Figure 4.1. Model showing the ancient shoreline of the northwestern Bay of Naples, Italy. 147

Figure 4.2. Drawings of the bottles depicting Puteoli: a) Mérida Bottle, b) Prague Bottle, c) Odemira Bottle, d) Pilkington Bottle. 149

Figure 4.3. Drawings of the fragments depicting Puteoli: a) Ostia Fragment, b) Cologne Fragments, c) Gorga Fragments. 150

Figure 4.4. Drawings of the bottles depicting Puteoli and/or Baiae: a) Populonia Bottle, b) Ampurias Bottle, c) Astorga Fragment, d) Warsaw Bottle. 151

Figure 4.5. Four views of the Mérida Bottle. 152

Figure 4.6. View of the Prague Bottle. 154

Figure 4.7. View of the Pilkington Bottle. 158

Figure 4.8. Three views of the Populonia Bottle. 160

Figure 4.9. Four views of the Warsaw Bottle. 163

Figure 4.10. Drawing of the Brescia Fragments. 164

Figure 4.11. View from the Archaeological Park at Baia, Italy. 169

Figure 4.12. View of the Villa San Gallo, Baia, Italy. 170

Figure 4.13. View of Pozzuoli, Italy, from a boat departing Baia’s harbor. 172

Figure 4.14. View of the Macellum, Pozzuoli, Italy. 174

Figure 4.15. View of the amphitheater’s subterranean corridors, Pozzuoli, Italy. 175

Figure 4.16. View of the Augustan temple, Rione Terra, Pozzuoli, Italy. 176

Figure 4.17. Bottle (from Zülpich, Germany) enameled with charioteers and the phrase Gallia Belgica. 179

Figure 4.18. Drawing of the Pesaro Fragment depicting a circus scene. 180

Figure 4.19. Gold-glass fragments (from Cologne, Germany) depicting an unidentified cityscape. 181

Figure 4.20. View of a cage cup (from Cologne, Germany) with a Greek exhortation. 185

Figure 4.21. Relief sculpture depicting a port city, Portus, Italy. 186

Figure 4.22. Fresco depicting a port city, Villa San Marco, Stabiae, Italy. 187

Figure 4.23. Fresco depicting a port city, Bay of Naples, Italy. 188

Figure 4.24. Engraving depicting a lost fresco (from Rome, Italy) depicting a port city. 189

Figure 4.25. Lamp depicting a port and fishermen, perhaps Carthage, Tunisia. 190

Figure 4.26. Lamp depicting a port and pier, perhaps Carthage, Tunisia. 191

Figure 4.27. View of a fresco depicting cupids in a harbor with three central figures, from the house beneath the Church of Saints John and Paul, Rome, Italy. 192

Figure 4.28. Sarcophagus depicting a port city, Ostia, Italy. 192

Figure 4.29. View of a mosaic depicting cupids in a harbor surrounded by porticoed buildings, Villa del Casale, Piazza Armerina, Italy. 194

Figure 4.30. View of a mosaic depicting a lighthouse, Forum of the Corporations, Ostia, Italy. 195

Figure 4.31. View of a glass jug (from Ptuj, Slovenia) depicting the lighthouse at Alexandria, Egypt. 196

Figure 4.32. View of the bridge at Mérida, Spain. 202

Figure 4.33. View of the theater at Mérida, Spain. 203

Figure 4.34. View of the portico with alternating shields and caryatids, Mérida, Spain. 204

Figure 4.35. Detail of a mosaic showing Ocean, Pharus, Euphrates, and Nile personified, from the House of the Mithraeum, Mérida, Spain. 205

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Haec autem nec sunt nec fieri possunt nec fuerunt. And such things neither are, nor can be, nor have been.

Vitruvius, On Architecture, 7, 5, 4

This line is my favorite in Latin literature. I love the terse phrasing and resolute rejection of the new. For Vitruvius, the new in question was a fantastical style of wall painting full of metamorphosing monsters and impossible buildings. For me, the words describe what would have happened to this book without the support of colleagues, friends, and family: neither existing, nor taking off into the future, nor ever undertaken at all.

The ideas for this book developed during two life-changing fellowships. The first allowed me to participate in a three-year traveling seminar entitled “The Arts of Rome’s Provinces,” co-directed by Natalie Kampen and Susan Alcock as part of the Getty Foundation’s Connecting Art Histories project. Spending a few weeks each year with leading specialists sharpened my thinking about how art functions in provincial contexts. The group’s rain-soaked hike along Hadrian’s Wall was also pivotal to my understanding of that site, featured in Chapter 3. My second opportunity was provided by the Pat O’Connell Memorial Fellowship, which allowed me to spend a sabbatical year at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. My understanding of glassware and enamelware deepened because I could consult objects in galleries on a daily basis. I was lucky to have my office located in the museum’s superb research library, where I had direct access to the stacks. I am indebted to the institution’s registrars and librarians, and especially my curatorial sponsor Melanie Holcomb. In my Romano-Byzantine cohort, Anne Hunnell Chen, Alice Lynn McMichael, and Erin Peters prompted me to pitch ideas whenever they occurred, whether literally at the water cooler or in the staff cafeteria. These fellowships offered far more than funding: they connected me to a community of scholars who challenged and enriched my way of thinking.

I have been fortunate to work with exceptionally generous curators. Ralph Jackson (British Museum), Christopher Lightfoot (Metropolitan Museum),

Alexandra Ruggiero (Corning Museum of Glass), and Katherine Larson (Corning Museum of Glass) made time to discuss their collections with me, pulled objects off view for photography and close study, and made available archival documents, recent publications, and new measurements. My analysis of the glassware and enamelware in this book would not have been possible without their collegial engagement.

From my home institution, Wellesley College, I benefited from research funds for travel, which allowed me to retrace the paths of some of the book’s artifacts. With departmental funding, I was able to hire excellent research assistants. Maya Nandakumar, Hana Sugioka, and Corinne Muller tirelessly proofed early drafts of the manuscript, managed the ever-growing bibliography, and provided muchneeded moral support. The Interlibrary Loan department of Clapp Library worked miracles, while research librarians Brooke Henderson and Jeanne Hablanian helped process an endless stream of book loans and purchases. Jordan Tynes and Shane Cox of the Knapp Technology Center scanned and digitally modeled replicas of the Spectacle Cups featured in Chapter 2, and these models were instrumental to my understanding of how the fragile originals were manipulated and read.

In the end, no one has listened to me complain about this book more than my mother, who is indefatigable and accompanied me on several memorable research trips. In the Bay of Naples, I displayed an astonishing lack of filial piety when I suggested that we hike along the edge of a two-lane highway after we missed a bus connection. It is thanks to her grit and determination that we made it to Baia in time for our reserved underwater boat tour of the harbor’s submerged villas. In Spain, we more successfully navigated the trains and buses that took us to Tarragona (where we toured the amphitheater without umbrellas during a downpour), Cádiz (where we lingered over the local wine), Italica (which we had to ourselves), and Seville (where the unending archaeological museum finally broke my mother’s spirit of adventure, and she opted to wait for me at the exit). I treasure all of our misadventures.

When I am asked what I like best about being a Roman art historian, I always say the travel. For students and colleagues, I happily transform into a travel agent for the Roman empire as I dispense advice about archaeological sites and museums (and nearby gelaterias, trattorias, and enotecas). I hope that this book’s readers will likewise be inspired to seek out the empire’s many mesmerizing destinations and their souvenirs.

ABBREVIATIONS

CIL Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

CSIR Corpus Signorum Imperii Romani

DMLBS Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources

ILS Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae

LTUR Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae

OED Oxford English Dictionary

OLD Oxford Latin Dictionary

PAS Portable Antiquities Scheme

RIB Roman Inscriptions of Britain

RIC Roman Imperial Coinage

Unless otherwise noted, references to primary sources are based on those in the digital Loeb Classical Library (https://www.loebclassics.com/), and translations are my own.

Introduction

En Route to the Roman Empire

When the Colosseum opened in the 80s ce, the poet Martial compared the new amphitheater favorably to five world wonders: the Memphis pyramids, Assyrian Babylon, the Ionian temple for Artemis, the Delian horned altar, and the Carian Mausoleum, all in the eastern Mediterranean or Mesopotamia.1 The poet was certainly a well-traveled respondent, with a successful career in Rome framed by a childhood and retirement in Spain. Yet there is no indication that he visited the buildings to which he relates the Colosseum. Celebrated as they were in literature, these sites could be conjured from afar.2 His words reveal a connoisseurship of places not just seen, but also imagined.

Place means more than defined space. As a flexible concept, place can denote a mapped location, a setting for social interaction, or a site made memorable by emotional connections and multi-sensory experiences.3 Places are therefore never static and passive, but ever-changing in their material and mental constructions. Understood in this way, place becomes fundamental to comprehending the Roman empire’s character and extent. The empire, for instance, was a place distinct from others due to the connectivity fostered by its standardized road system and secured shipping lanes. This is the context in which a Spanish poet might see Rome’s Colosseum in person and acquire knowledge of other sites indirectly through oral histories, circulating manuscripts, or mobile material culture. In his poem, Martial evokes nuanced notions of place on a number of scales, from the empire as an expansive setting with inherited cultural wonders, to the city of Rome as a site of architectural innovation, to the Colosseum as a new venue for wonderment.4

Alluring portrayals of place survive in Roman literature and art and—somewhere in between these two categories—on the objects that inspired this book. Scholars refer to them as souvenirs, and this class of artifact is just beginning to receive the serious analysis it deserves in Roman studies. This is one point that Ernst Künzl and Gerhard Koeppel make in their groundbreaking survey of souvenirs dating from antiquity to the present day.5 They argue that the Romans invented the genre.

Destinations in Mind. Kimberly Cassibry, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190921897.003.0001

More recently, Maggie Popkin has built on their work and interpreted the objects in relation to urbanism and cultural memory.6 She also engages with the sociological field of souvenir studies. In the same vein, this book was supposed to be about memories made miniature. Yet a souvenir, strictly defined, should perpetuate personal memories, and I became frustrated trying to find those in the archaeological record.7 I could tell which objects had the potential to bear such cognitive investment, but not whether they ever actually had. Meanwhile, the global, material, and sensory discourses in Roman studies began to suggest new lenses of analysis, ones that allowed me to see conceptions of place in a global empire and processes of portrayal in a multicultural one, both mediated by lived experiences of settings and materials. Approached in this way, material that had previously been mute began to speak. So I set aside questions of memory and focused on vessels bearing words and images that allowed the site represented to be identified with certainty. I now think of them as portable portrayals of place.

What surprised me most about the artifacts in my study was their relative rarity: four series of vessels most clearly met my criteria. I call them the Itinerary Cups, the Spectacle Cups, the Fort Pans, and the Bay Bottles. They are considered in turn in the book’s four chapters, described more fully at the end of the Introduction. The material’s allure, however, merits a bit of foreshadowing here. The first series is made of lustrous silver engraved with itineraries connecting Spain to Rome: each cup bears a slightly different list of about a hundred stops. They conjure the Roman road system and its journeys and in doing so raise the book’s fundamental question: how did residents compare places when not all were described in literature and when so few were represented on circulating objects? The second case study addresses colorful mold-blown cups depicting and naming either charioteers in Rome’s Circus Maximus or gladiators in an undefined arena. This discrepancy in setting will be the second chapter’s chief focus because it illuminates how craftsmen responded to the empire’s entertainment venues. Picking up the surviving cups and considering them in motion reveals how experiences of these spaces were miniaturized and recreated in translucent glass. The third chapter takes us to the Celtic borderland marked by Hadrian’s Wall in England. Small cast bronze pans, exquisitely enameled, name a select sequence of forts along the wall. The place names are glossed with either fortified wall motifs or Celtic emblems. These vessels invite us to consider the aesthetics of place in a multicultural empire. The Bay Bottles, in turn, take us back to Italy, to the Bay of Naples. A series of fine glass bottles bear depictions of the buildings at Baiae, the empire’s preeminent spa, and neighboring Puteoli, a major international port. In this case, labeled cityscapes come into focus for the first time as subjects for collectible vessels. Altogether, the case studies illustrate explorations of place on several scales, from sports venues, to seaside cities, to a fortified frontier, to an imperial road system. They also contextualize the city of Rome as one destination among many.

Previously, these artifacts have been mined for the information they preserve about particular sites. Yet their portrayals reward deeper analysis. The vessels’ continuous curved surfaces, for instance, offered more expansive canvases than did coins (the empire’s primary medium of propaganda). Their functional shapes invited more regular handling and perusal than did scrolls or relief sculptures (the dominant media for historical narratives). Vessels could and still can be picked up, turned, and read. Doing so reveals that their materials inflected legibility and meaning more acutely than did other supports for words and images, whether papyrus or stone. Their long-distance dispersal, moreover, circulated place-based knowledge in ways that can still be assessed. We may never know, for instance, whether anyone in Emerita Augusta (modern Mérida) learned of Rome and its Colosseum by reading Martial’s poetry, because so few ephemeral manuscripts survive. We may, however, reasonably assume that at least one of its residents knew of Puteoli, because a Bay Bottle portraying that Italian cityscape has been excavated in that colony. That some of the buildings depicted and labeled—not least the amphitheater—appeared in both cities gave residents opportunities to compare urban amenities. In these and many other ways, portable portrayals could bring distant places into dialogue in their beholders’ minds. I wrote Destinations in Mind in order to understand this imperial phenomenon and the role that mobile material culture played in producing it.

Part of the artifacts’ value lies in their defiance of the categories scholars have established to organize the Roman empire’s study. They are simultaneously material texts and portable works of art. They are handheld objects that depict largescale buildings, cities, frontiers, and roads. They are Roman, Italian, and provincial in their sites of production and use. A deeper analysis therefore requires knowledge of diverse regions, as well as the methodologies of archaeology, art history, ancient history, and philology. In confounding boundaries—categorical, geographic, and disciplinary—the portable portrayals become ideal tools for seeking new understandings of a global empire defined by its places.

Notions of the global, and of places within it, merit elaboration, as do theories of materiality and sensory experience. The subsequent two sections locate my interdisciplinary analysis more fully within these research trajectories. An orientation and user’s guide to the book’s chapters then follows.

Places in a Global Empire

Globalization has been assessed within the Roman empire for several decades and has become an established area of study. Place, on the other hand, has been explored in more discrete fashion and has, curiously, been of limited interest to those concerned with globalization. The portable portrayals require both discourses to be in play.

Approaching Place

For the past several decades, scholars in the field of geography have sketched useful contours around a concept that is widely used, but rarely defined. These definitions prompt us to look beyond the physical evidence and to think more holistically about interconnected places in a global empire.

As Tim Cresswell and others have noted, there are several ways in which place might be invoked: as a location (a site that can be mapped), a locale (a material setting for social life), or a sensibility (a sense of place, with emotional and subjective investment).8 To apply these definitions to a Roman example, the Colosseum was certainly a location that could be mapped in relation to the city’s other buildings, as it was on the ancient marble plan of Rome (Forma Urbis Romae, c. 200 ce).9 In this locale, spectators sat together to observe staged combat, which Martial reports in great detail in his suite of epigrams about the Colosseum’s spectacles.10 These events associated the building with violence, a sense of place that endures even though ritualized bloodshed has not darkened the arena since late antiquity. Recognizing these aspects of place will help us observe new nuances in the portable portrayals’ communication.

Many geographers caution against approaching place as a static entity. They instead find notions of place in dynamic negotiations subject to external factors and informed by multiple internal identities and histories. Championing this approach, Doreen Massey has argued that social networks and routes, rather than roots and borders, should be central to knowing places, which can be introverted or extroverted in a global context.11 To return to Martial’s book of poems about the Flavian amphitheater, one epigram describes Nero’s self-centered pleasure villa and lake, the place that the Colosseum literally replaced for the broader benefit of the Roman people, in what could be read as the site’s dynamic transition from introversion to extroversion.12 A further poem lists all of the distant peoples, including Ethiopians and Arabs, who came to be spectators. In Martial’s evocation, the Colosseum becomes a central node in a network of far-reaching paths, or an even more extroverted place, to use Massey’s term again.13

Geographers have also addressed the impact that colonization and globalization have had on place-making. In what has become a classic essay about an Alaskan ghost town attached to an abandoned mine, William Cronon highlights imported notions of place, especially foreign ideas of ownership and the far-reaching supply chains that can feed or starve a remote site.14 Cronon addresses land that US prospectors seized from Native Americans, and his observations remind us to be attentive to the imposition of Roman administrative notions of place. Regions redefined as Roman provinces gained new roads and boundaries, cadastral surveys apportioned land to colonists, and distances measured in miles and announced on milestones abetted martial as well as commercial movement. Yet many conquered lands had already been measured, and pre-Roman units of length persisted in use, specifically Gallic

leagues and Greek stades.15 Roman roads, moreover, often standardized pathways of long use. It bears reiterating that conquest rarely brought about a first encounter between “Romans and natives.” It instead marked a culmination of contact, which sometimes stretched back for centuries and almost always involved third parties. As we follow the movement of the portable portrayals, keeping track of their place in time will matter. By 100 ce, many regions had been under Roman rule for a century or more but had been involved in Mediterranean-wide trade for far longer. Discerning what registered as familiar or foreign at any given site can be a challenge.

To that end, geographers have also pondered placelessness, a topic that gains urgency in any era of globalization, as sites come to resemble one another in their heterogeneity.16 We, for instance, may now enjoy (or lament) finding a Starbucks on every corner, wherein a selection of coffee varietals from distant continents are ground, brewed, and then served in cups with a standard logo. In comparison, residents roaming the western Roman empire could expect to find a forum (a plaza with key civic and religious buildings) in most towns, with affluence displayed in the diversity of stones selected from the cross-continental marble market.17 In the past, such sites have been described through the contested dialectic of Romanization (e.g., the forum) and localization (e.g., usage of local stones), with one prioritized over the other according to the scholar’s proclivity for seeking similarity or difference in the material record.18 Again, globalization complicates this scenario in part by highlighting third terms (e.g., stones quarried in locations that were neither local, nor in Italy, but instead in Tunisia, Turkey, or Greece). As we consider what might make a place in a global empire distinct, the environment itself matters. The amphitheaters at Puteoli and Mérida, for instance, may have had in common building types, gladiatorial events, and even latitudinal positions on the globe, but their materials differed, as did their urban terrain and longitudinal locations. These environmental factors had profound implications for views, daylight, and weather, as well as residents’ implicit biases about how places were supposed to be. Environment therefore should be one of the factors considered when discrepant experiences of empire are assessed. Portable portrayals offer an opportunity to pursue this question further, through the geographic networks created by their subjects and findspots.

Roman Places

English usage of the word “place” informs the studies described in the previous section, so it would be fair to ask if Romans had a similar term.19 They did, though curiously not the term from which “place” derives. “Place” has roots in the Greek plateia and the Latin platea. 20 Referring to a broad street or avenue, the original sense survives more clearly in the modern usage of piazza or plaza 21 It was instead the Latin word locus that possessed the range of associations that “place” does now.22 Locus was therefore much broader in its original semantics than its modern

derivatives “location” and “locale” would suggest.23 Tellingly, locus also featured in the phrase genius loci, meaning the spirit of a place.24 For the empire’s polytheists, a place could be propitiated through its spirit, and the related concept could operate on a supernatural register as well.

References to meaningful places permeate the empire’s culture, whether in oratory, spectacle, literature, science, or art. Ann Vasaly, for instance, has shown how Cicero made his speeches more persuasive by invoking places dear to his audience.25 Similarly, Popkin has pointed out that triumphal processions in Rome programmatically passed sites crucial to cultural memory in order to connect past and present achievements.26 Immense paintings of conquered places featured in these processions, and then were displayed in victory temples and public porticoes, as Peter Holliday has shown.27 Place was also the central focus of several well-studied genres of literature. Pausanias’ travelogue of his Greek homeland combines physical descriptions of sites, such as the Athenian acropolis, with historical anecdotes.28 Strabo’s Geography described the lands, peoples, and customs of the known world, whereas Ptolemy’s Geography compiled systematic measurements of latitude and longitude for all major cities.29 In addition to these anecdotal and scientific engagements with particular places, types of places could also be invoked. Villas, for instance, were the subject of detailed literary description (ekphrasis), as well as generic fresco paintings.30 The latter recur on the walls of Pompeii’s townhouses, where they conjured the experience of cultivated leisure (otium) far from the urban spaces of business (negotium).31 Although the scholarship surveyed here does not necessarily engage with geography’s discourse on place, it is nonetheless sympathetic in revealing ancient interest in locations (e.g., Ptolemy’s Geography), locales (e.g., triumphal routes), and senses of place (e.g., luxurious villas).

A more direct focus on place-making is emerging. In the edited volume Making Roman Places, Past and Present, for instance, the authors look beyond the physical features of sites to consider the meanings created by diachronic use.32 Yet each essay defines place differently, and some use the word to denote space (which has a distinct historiography).33 What unifies the essays instead is their constructivist approach, the contention that meanings are not inherent but created, and that is a commitment that this book shares.34 Darrell Rohl’s recent essay “Place Theory, Genealogy, and the Cultural Biography of Roman Monuments” is more explicit in building connections to the concepts developed in geography. His essay makes an important contribution by synthesizing the discourse for an archaeological audience, then applying it to Roman sites and their management as cultural heritage.35 The present book joins Rohl’s study in drawing on geography’s theories of place. Before we turn to the scholarship related to the vessels’ other aspects, two characteristics of ancient approaches to place need to be set out.

First, describing the known world, as well as Rome’s dominion of it, required strategies that compressed time and space between places. One approach was to focus on highlights, as Martial did.36 Rather than stating outright that the

Colosseum was the greatest architectural undertaking the world had ever seen, he compared the amphitheater to wondrous constructions of the past, in a list of sites that could be read in seconds, but which would have required months, if not years, to visit in person. A comparable approach is evident in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, just a day’s journey from Rome.37 During an afternoon’s stroll across the grounds, one could experience recreations of the emperor’s favorite places, from the Knidian Temple of Aphrodite to the Egyptianizing shrine for his beloved Antinous, who had drowned while swimming in the Nile. If the desire was instead to represent all of Rome’s conquered lands and peoples, then they could be made manifest in personifications, such as those featured on coin issues or in stone relief sculptures, including those in Rome’s Temple to the Divine Hadrian (the Hadrianeum) and in a sanctuary (the Sebasteion) at Aphrodisias.38 Globes could be mobilized, too. Roman authors often equated the empire’s territory with the orbis terrarum (literally the “orb of lands,” often translated as “the world”).39 In art, when personified victories touch their feet to miniature spheres, they communicate global dominance. Those in the spandrels of Rome’s Arch for Titus are a good example. Such verbal and visual conventions rhetorically recast the empire’s limits, for Rome’s reach did not in truth extend to all of the lands then known. Juvenal, for instance, denotes these larger bounds when he opens his tenth satire with the phrase, “in all the lands from Gades, to the dawn and the Ganges.”40 Spanish Gades signaled the world’s western edge, whereas the Indian Ganges referred to an eastern one. Rome claimed the former, but not the latter. Like Martial, Juvenal trusted his readers to fill in the space between the places that he juxtaposed with great economy. This trust is all the more remarkable at a time when integrated maps as we know them—with locations plotted and labeled, land contours visualized and rendered to scale, and integrated routes through them identified and measured—were seldom used, if they existed at all.41 Ancient mentalities about mapping informed the readership that the portable portrayals anticipated in their verbal and visual contractions, and will be explored in Chapter 1.

Second, given that notions of place draw upon actions, experience, and hearsay, as much as setting, it should not be surprising that portrayals did not strictly prioritize factual accuracy. Depictions of architecture, in particular, deviate substantially from known facts. In images of complex cityscapes, for instance, buildings are typically angled so that their most recognizable sides (often their fronts) are visible, rather than being shown as they appeared altogether from a single point of view.42 Moreover, key details of distinctive buildings, say the round temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum, could change across different media and in varied scenes, as Melanie Grunow Sobocinski has shown. These alterations include numbers of columns, which scholars had previously thought were essential to identification, but which can vary if other identifiers are present, such as a legend or a recognizable cult statue.43 With accuracy subordinate to other factors, parsing a building’s rhetorical function in a composition becomes paramount. This is especially true of