Introduction

THE END OF EDUCATION

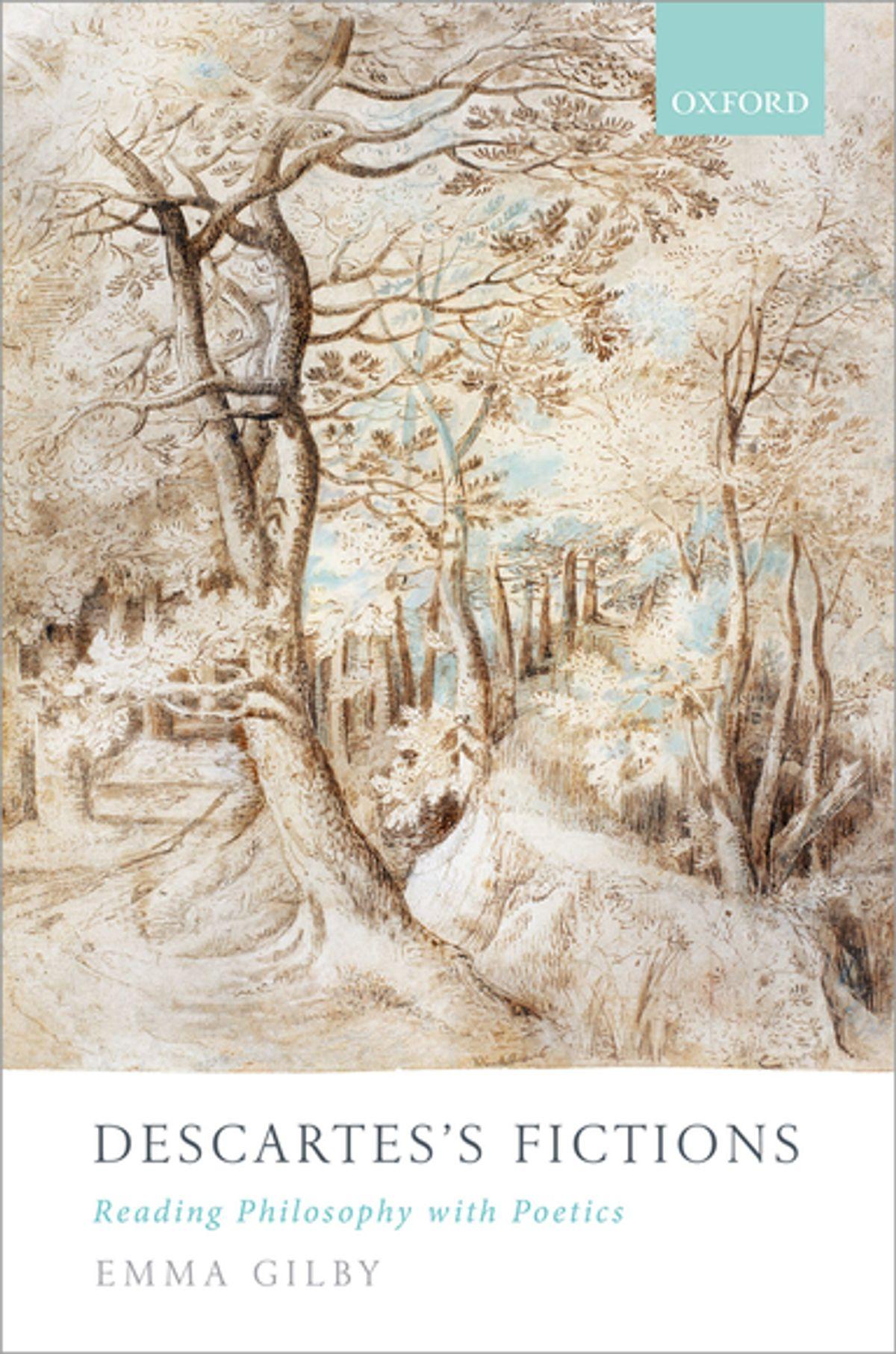

When writing about Descartes, critics have tended to start with his own mission statements. Descartes is known for the strength of his philosophical self-assertion: for his determined statements of intent, and for his ambitious conclusions. He seeks to undermine the existing Aristotelian framework for knowledge, dismissing it as prejudice. Thus he wants to erase scholastic obscurity, and produce philosophy that is open to everyone.

When Descartes laments the power of prejudice, he starts with that imparted by his own education, at the hands of the Jesuits. Although he was ‘nourri aux lettres dès mon enfance’ (‘educated in classical studies from my earliest years’), he has derived no profit from his years at school, other than that of progressively revealing to himself how ignorant he is.1 The ‘sciences des livres’—the accumulated opinions of generations of scholars—are no closer to the truth than ‘les simples raisonnements que peut faire naturellement un homme de bon sens touchant les choses qui se présentent’ (‘the simple reasoning that any man of good sense can produce about things in his purview’) (AT VI, 12‒13; Discourse, p. 13). This powerful anti-nostalgia extends beyond Descartes’s schooldays to his childhood as a whole. At the very beginning of the Meditations of 1641, Descartes’s meditator is struck by ‘how many false opinions I had accepted as true from childhood onwards’, and by the doubtful nature of ‘whatever I had since built on such shaky foundations’ (AT VII, 17).2 He realizes at this point that ‘the whole structure will have to be utterly demolished’, and that ‘I should have to begin again from the bottom up if I wished to construct something lasting and unshakeable in the sciences’ (AT VII, 17). Descartes hereby rejects the force of custom: the lifelong belief that things are just as our senses perceive them to be. Instead, he espouses a radical form of doubt. Tracing out complex gradations of knowledge, awareness, opinion, and belief, he

1 Œuvres de Descartes, ed. Charles Adam and Paul Tannery, 11 vols. (Paris: Léopold Cerf, 1897–1910; repr. Paris: Vrin, 1996), vol. VI: Discours de la méthode et essais, p. 4. Subsequent references will appear in the text and footnotes using the abbreviation AT before the volume and page numbers. A Discourse on the Method, trans. Ian Maclean (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2006), p. 7. English translations from the Discourse will be from this edition.

2 René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, with Selections from the Objections and Replies, trans. Michael Moriarty (Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 2008), p. 13. English translations from the Meditations, Objections, and Replies will be from this edition, abbreviated as MM, unless mentioned otherwise. Descartes’sFictions:ReadingPhilosophywithPoetics. Emma Gilby, Oxford University Press (2019).

obser ves that to believe things is not to know them, nor even to know that one believes them.

When the professors of the Academy of Utrecht reject Descartes’s new philosophy in the early 1640s, it is, in part, because they judge it to have succeeded absolutely in his destructive aims: ‘It is opposed to the traditional philosophy which universities in the whole world have hitherto taught on the best advice, and it undermines its foundations’ (AT VII, 592).3 But it is also because its immediate newness is seen as somehow amplificatory, preventing any future engagement with the past:

It turns young people away from the ancient, sound philosophy and prevents them from reaching the pinnacle of erudition because, by relying on this pretence of philosophy, they can no longer understand the technical terms used in the books of renowned authors and the lectures and disputes of their professors. (AT VII, 592‒3)

If Descartes has suspicions about education, education also has suspicions about Descartes. Descartes is on his own. And this solipsism, imaged in the stove-heated room in which Descartes once passed an influential day of solitary reflection and enlightenment, has come pervasively to stand in for his philosophy as a whole.4

Descartes is seen to make individuation, rather than any kind of interactive learning, the defining condition of personhood. His meditator requires nobody else—no second-order criticism, no compilation of commonplaces—to imagine his radical sceptical hypothesis: that all our perceptions have been manipulated by a powerful evil spirit (AT VII, 21‒3). Taking scepticism to a new extreme, he shows that this way of thinking negates itself by revealing a fundamental certainty: the certainty that if I am thinking, I must exist (AT VII, 27‒9). Thought is ‘everything that takes place in us, while we are aware, in so far as there is awareness of it in us’.5 Thus defined, it is distinct from physical processes, and the meditator’s certainty does not require sensation in any way, shape, or form. In this way, Descartes feels that he achieves his goal of rejecting the Aristotelian attempt to

3 These translations are from Desmond M. Clarke, Descartes: A Biography (Cambridge University Press: 2006), p. 228. See also René Descartes and Martin Schoock, La Querelle d’Utrecht, ed. Theo Verbeek (Paris: Les Impressions nouvelles, 1998), p. 121.

4 ‘J’étais alors en Allemagne, où l’occasion des guerres qui n’y sont pas encore finies m’avait appelé; et, comme je retournais du couronnement de l’empereur vers l’armée, le commencement de l’hiver m’arrêta en un quartier où, ne trouvant aucune conversation qui me divertît, et n’ayant d’ailleurs, par bonheur, aucuns soins ni passions qui me troublassent, je demeurais tout le jour enfermé seul dans un poêle’ (AT VI, 11). ‘At that time I was in Germany, where I had been called by the wars that have not yet come to an end there; as I was returning to the army from the coronation of the emperor, I was halted by the onset of winter in quarters where, having no diverting company and fortunately also no cares or emotional turmoil to trouble me, I spent the whole day shut up in a small room heated by a stove’ (Discourse, p. 12). Baillet dates this to November 1619, when Descartes also apparently had three influential dreams, in one of which he remembered a line from Ausonius: ‘what path in life shall I follow?’ The details of these only became known after his early papers, extracts of which are known as the Olympica, were circulated after his death. See Adrien Baillet, La Vie de Monsieur Descartes (Paris: Horthemels, 1691), book II, chapter 1, p. 81; and AT X, 180–8. The account in the Olympica overlaps with those papers given as the Cogitationes Privatae (Private Thoughts) in AT X, 213–48 (p. 215).

5 Principles of Philosophy, Part 1, article 9, in Descartes, The Passions of the Soul and Other Late Philosophical Writings, trans. Michael Moriarty (Oxford World’s Classics: Oxford, 2015), p. 139.

ground knowledge in sense-experience. Instead, we must base knowledge on our own clear and distinct ideas. Pursuing such a goal also means establishing a rational basis for religious belief: knowing that God exists, and is not a deceiver (AT VII, 36). Descartes’s ambition, to borrow a phrase from Pascal, is eye-popping.6

Thus it is that Descartes’s work is often taken as a turning point: the end of medieval thought, and the beginning of a modern identification of thinking and being, or, one might say, of ‘consciousness and existence, egoity and substantiality’.7

This Descartes is a necessary enemy, anathematized, enslaving, but also granted an extraordinary status and pre-eminence. The advent of his philosophy is a transformative event that is ruthless, as well as radical: Descartes’s work is seen to embody a brutal dismissal, in the name of a joyously unfettered reason, of the entire edifice of ancient knowledge and wisdom. For Michel Foucault, Descartes is emblematic of the new classical age, in which the world is conceived in terms of mutually reinforcing taxonomies that are subject to calculation and manipulation.8

For literary theorists with an interest in autobiography, Descartes is seen to inaugurate a view in which the act of ‘unsituating the self from the world’ is ‘transformed

6 ‘Mais l’infinité en petitesse est bien moins visible. Les philosophes ont bien plutôt prétendu d’y arriver, et c’est là où tous ont achoppé. C’est ce qui a donné lieu à ces titres si ordinaires, Des principes des choses, Des principes de la philosophie, et aux semblables aussi fastueux en effet, quoique moins en apparence que cet autre qui crève les yeux: De omni scibili.’ Pascal, Pensées, ed. L. Lafuma (Paris: Seuil, 1962), fragment 199. ‘But the infinitely small is much harder to see. The philosophers have much oftener claimed to have reached it, and it is here they have all stumbled. This has given rise to such familiar titles as First Principles, Principles of Philosophy, and the like, which are really as pretentious, though they do not look it, as this eye-popping example, Of All That Can Be Known.’ On this fragment, see Vincent Carraud, ‘Approfondir trop et parler de tout. Les Principia philosophiae dans les Pensées (note complémentaire sur “Disproportion de l’homme”)’, Revue d’histoire des sciences, 58.1 (2005), pp. 29–52.

7 ‘The identification of the “I” with subjectivity, by contrast, is a specifically modern phenomenon, whose origin lies in the work of the very thinker commonly taken to seal the irrevocable end of medieval thought, namely Descartes. Only after the Cartesian project to conceive of certitudo cognitionis humanae as the sole and absolute fondamentum inconcussum veritatis is the “I” considered as a subject, such that consciousness and existence, egoity and substantiality, become strictly correlative.’ Daniel Heller Roazen, Fortune’s Faces: The Roman de la Rose and the Poetics of Contingency (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), p. 31.

8 ‘La critique cartésienne [. .] est la pensée classique excluant la ressemblance comme expérience fondamentale et forme première du savoir, dénonçant en elle un mixte confus qu’il faut analyser en termes d’identité et de différences, de mesure et d’ordre.’ Michel Foucault, Les Mots et les choses. Une archéologie des sciences humaines (Paris: Gallimard, 1966), p. 66. ‘The Cartesian critique [. . .] is Classical thought excluding resemblance as the fundamental experience and primary form of knowledge, denouncing it as a confused mixture that must be analysed in terms of identity, difference, measurement, and order.’ The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London and New York: Routledge Classics, 2002), p. 58. See also Les Mots et les choses, p. 89: ‘En tout cas, l’épistémè classique peut se définir, en sa disposition la plus générale, par le système articulé d’une mathesis, d’une taxinomia et d’une analyse génétique. Les sciences portent toujours avec elles le projet même lointain d’une mise en ordre exhaustive: elles pointent toujours aussi vers la découverte des éléments simples et de leur composition progressive; et en leur milieu, elles sont tableau, étalement des connaissances dans un système contemporain de lui-même.’ The Order of Things, p. 82: ‘In any case, the Classical episteme can be defined in its most general arrangement in terms of the articulated system of a mathesis, a taxinomia, and a genetic analysis. The sciences always carry within themselves the project, however remote it may be, of an exhaustive ordering of the world; they are always directed, too, towards the discovery of simple elements and their progressive combination; and at their centre they form a table on which knowledge is displayed in a system contemporary with itself.’

into a condition of the self’s authentic nature’.9 Epistemology in the Anglo-Saxon philosophical tradition is no less dependent upon a narrative of novelty: for Richard Rorty, epistemology requires as a minimum a field of study called ‘the human mind’—‘and that field of study was what Descartes had created’.10

To echo Descartes echoing Lucretius, one might say that nothing comes from nothing.11 Much recent work has pushed compellingly beyond the standard responses to Descartes. Roger Ariew has pointed out the forms of commonality between Descartes’s work and a prior scholastic reception of ancient thinking.12 Critics have also focused on the way that the mind-body split so crucial to the narrative of novelty in the first Meditation occurs only provisionally in Descartes’s work, given his fascination with psychophysical sensation and the workings of the imagination.13 Feelings of thirst, hunger, pain, and so forth are modes of thinking that arise from the fusion of the mind with the body (Sixth Meditation; AT VII, 81), as do the passions, elaborated upon in Les Passions de l’âme of 1649. Whether we consult (to be brief) Geneviève Rodis-Lewis on Descartes’s anthropology; Susan James or Michael Moriarty on the importance to Descartes of our status as embodied, passionate beings; or Desmond M. Clarke on critical confusion about Descartes’s theories of mental functioning, we find a questioning of the transparent certainty often imputed wholesale to the Cartesian mind.14

In his introduction to The Matter of Mind , Christopher Braider negotiates different positions, referring to Hans Blumenberg’s The Legitimacy of the Modern Age on the one hand and to Foucault on the other:

The Cartesian ‘invention of the mind’ was not just the heroic break with prejudice, fantasy, and error that Blumenberg chronicles. But neither was it simply the hubristic mask for the new rationalist tyranny epitomized by Foucault’s favourite icons of

9 ‘The Autobiographical Situation’ in Janet Varner Gunn, Autobiography: The Poetics of Experience (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982), pp. 3–29 (p. 7).

10 Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979), p. 140.

11 Descartes refers to the common notion that ‘a nihilo nihil fit’ in his responses to the second objections to the Meditations (AT VII, 135). The most obvious point of reference is Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, ll. 149–50. As we shall see, Descartes also observes the theological point that God created the universe ex nihilo

12 Roger Ariew, Descartes Among the Scholastics (Leiden: Brill, 2011). See also Lilli Alanen, Descartes’s Concept of Mind (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003).

13 John Cottingham therefore prefers ‘trialism’ to ‘dualism’, with particular reference to the letter of Elisabeth of 21st May 1643 (AT III, 665): ‘Cartesian Trialism’, Mind, 94.374 (April 1985), pp. 218–30.

14 The monumental French tradition of Cartesian criticism has always, in any case, worked from an historicizing impulse that counters generalizations about the Cartesian subject. The references above are to Geneviève Rodis-Lewis, L’Anthropologie cartésienne (Paris: PUF, 1990); Susan James, Passion and Action: The Emotions in Seventeenth-Century Philosophy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997); Michael Moriarty, Early Modern French Thought: The Age of Suspicion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); Desmond M. Clarke, Descartes’s Theory of Mind (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003). See also Erec R. Koch, The Aesthetic Body: Passion, Sensibility and Corporeality in Seventeenth-Century France (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2008); and Rebecca Wilkin, ‘Descartes, Individualism and the Fetal Subject’ in d i f f e r e n c e s: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 19.1 (2007), pp. 96–127. With the latter I share a wager and a goal: that ‘depriving individualism of its alleged “man-midwife” will go further toward subverting an individualist ideology than simply reiterating this genealogy to bemoan it’ (p. 120).

the modern technocratic state—the insane asylum, the panoptical prison, and the barracks-like public school.15

Instead, it is a ‘perplexed response’ (p. 3) to a specific historical moment, inevitably entangled in modes of physical, psychological, and cultural embodiment. No less than the poets and thinkers who populated the worldly ‘salons’ and learned ‘cabinets’, Descartes uses his work to forge a social legitimacy for himself. It would be simplistic to regard the wealth of contemporary texts exploring the art of poetry as neutral intellectual foundations for a smoothly classical theatrical practice, without noting the extent of their socio-political positioning.16 Similarly, it would be naïve to neglect the worldly forces shaping Descartes’s assertions of autonomy at the same historical moment.

An obvious next step is to triangulate: to bring Descartes’s philosophical output into contact with the literary treatises, exempla, and controversies of that same historical moment. Many have theories of poetics at their core—accounts of literary possibilities and conventions that are central to the Western tradition of criticism from Aristotle on—and these theories provide a crucial intellectual context for his work. I shall therefore be paying close attention to the processes of active reading, watching, and listening that were so vital to early seventeenth-century French debates about tragedy and tragicomedy, as these deal with the Aristotelian topoi of imitation, wonder, heroism, verisimilitude, and belief.17 I shall also be arguing that, when corresponding with contemporaries such as Guez de Balzac, Marin Mersenne, and Constantijn Huygens (themselves profoundly embedded within the early modern republic of letters), Descartes draws upon their imaginative orderings and their choices of narrative. His work exists in the same transitional space as theirs.18 He seeks a role for himself amidst the profuse interconnections of his contemporaries’ formulations.

Writers and critics of the early seventeenth century return again and again to the relationship between literary works and the attentiveness that is their object. We are continually asked to evaluate the divergences between history and fable,

15 Christopher Braider, The Matter of Mind: Reason and Experience in the Age of Descartes (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012), p. 3, quoting Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, chapter 1.

16 See Déborah Blocker, Instituer un ‘art’. Politiques du théâtre dans la France du premier XVIIe siècle (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2009).

17 ‘La fréquence et la violence des querelles littéraires tout au long du siècle indiquent l’importance prise alors par la littérature, puisque c’est à travers elle qu’une grande part de la conflictualité sociopolitique réussit à se dire.’ (‘The frequency and violence of literary quarrels across the century indicate the importance of literature at that time, as so much sociopolitical conflict finds expression within it.’) Hélène Merlin-Kajman, ‘Un siècle classico-baroque’, XVIIe siècle, 56.2 (April 2004), pp. 163–74 (p. 164). See also L’Absolutisme dans les lettres et la théorie des deux corps (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2000); and ‘Un nouveau XVIIe siècle’, Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France, 105 (January–March 2005), pp. 11–36.

18 I am evoking here the terminology of the Mouvement Transitions, founded in 2010 by Hélène Merlin-Kajman, whose aims have recently been summed up in the latter’s Lire dans la gueule du loup. Essai sur une zone à défendre, la littérature (Paris: Gallimard, 2016). Hélène Merlin-Kajman references the transitional spaces and objects of psychoanalytic theory in order to consider how modes of ‘partage’ (sharing, distribution) condition both the production of literature and the way we apprehend its effects. See http://www.mouvement-transitions.fr/.

between reality and imitation, between truth and verisimilitude. Thinking in 1623 about readerly belief and how it is granted, Jean Chapelain observes the imperfections of history, and insists that history itself, to be plausible or verisimilar (‘vraisemblable’), will require manipulation: ‘De deux histoires contraires ou diversement racontées on suit toujours celle qui a le plus de probabilité’ (‘Of two stories which are opposing or differently told, we always follow that which is more probable.’)19 Poetry, by which is also meant verse drama, is one of the ‘sciences sublimes’, and not far from philosophy (p. 197). Unlike history, poetry

met le premier en considération l’universel et ne le traite particulièrement qu’en intention d’en faire tirer l’espèce, à l’instruction du monde et au bénéfice commun. (p. 197) brings the universal to our consideration first, and only deals with particularities in the intention of drawing out their kind, for the instruction of everyone and for the common good.

Chapelain is aiming at nothing less than universal benefit.

In his Discours de la méthode, Descartes says that he has learnt all sorts of lessons about the use value of literature. Thanks to his school curriculum, he knows that fables stimulate the mind, and that the memorable deeds recorded in histories uplift it, helping to form our judgement in a discerning way; he knows that reading good books is like engaging in conversation with the most distinguished minds of the past, and that oratory can be incomparably powerful; he knows that poetry can be both delicate and compelling, and that philosophy enables us to speak plausibly about anything at all.20 Famously, he goes so far as to put forward his own ‘Discours’ as a fable:

Ne proposant cet écrit que comme une histoire, ou, si vous l’aimez mieux, que comme une fable, en laquelle, parmi quelques exemples qu’on peut imiter, on en trouvera peut-être aussi plusieurs autres qu’on aura raison de ne pas suivre, j’espère qu’il sera utile à quelques uns sans être nuisible à personne, et que tous me sauront gré de ma franchise.21 (AT VI, 4)

But as I am putting this essay forward only as a historical record, or if you prefer, a fable, in which among a number of examples worthy of imitation one may also find several which one would be right not to follow, I hope that it may prove useful to some people without being harmful to any, and that my candour will be appreciated by everyone. (Discourse, p. 7)

As many critics have noted, the first-person insistence on exemplarity without prescription reminds us of Montaigne’s ‘Du repentir’: ‘Les autres forment l’homme, je le recite’ (‘Others form man; I tell of him’).22

19 Jean Chapelain, ‘Lettre ou discours de Monsieur Chapelain à Monsieur Favereau, Conseiller du Roi en sa Cour des Aides, portant son opinion sur le poème d’Adonis du Chevalier Marino’, in Alfred C. Hunter (ed.) and Anne Duprat (rev.), Opuscules critiques (Geneva: Droz, 2007), pp. 185–221 (p. 197).

20 See AT VI, 5–6; Discourse, pp. 7–8.

21 A ‘fable’ can be any kind of fictive narration, from the epics of Homer or Virgil to Ovid’s mythological poetry to Aesop.

22 Michel de Montaigne, Essais, ed. Pierre Villey (Paris: PUF, 1965), vol. III, ch. 2, p. 804; ‘Of Repentance’ in Donald M. Frame (trans.), The Complete Works (New York: Alfred A. Knopf [Everyman’s

But Descartes also clarifies in the first part of the Discours that history itself, the story of lives, is not the domain of truth claims or straightforward utility. Rather like Chapelain, he notes that we need to be aware of the value-laden modifications that are necessarily made to history in the telling:

Même les histoires les plus fidèles, si elles ne changent ni n’augmentent la valeur des choses pour les rendre plus dignes d’être lues, au moins en omettent-elles presque toujours les plus basses et moins illustres circonstances [. .]. (AT VI, 7)

Even if the most faithful of accounts of the past neither alter nor exaggerate the importance of things in order to make them more attractive to the reader, they nearly always leave out the humblest and least illustrious historical circumstances [. . .].

(Discourse, p. 8)23

The reader is confronted with a divergence between the writer and the ‘reality’ or particularity of written history, rendering the lessons that can be drawn from the latter unreliable and illusory, so that:

le reste ne paraît pas tel qu’il est, et que ceux qui règlent leurs mœurs par les exemples qu’ils en tirent, sont sujets à tomber dans les extravagances des Paladins de nos romans, et à concevoir des desseins qui passent leurs forces. (AT VI, 6‒7)

what remains does not appear as it really was, and that those who base their behaviour on the examples they draw from such accounts are likely to try to match the feats of knights of old in tales of chivalry and set themselves targets beyond their powers.

(Discourse, pp. 8‒9)

Such people sound very like Don Quixote after his reading of chivalric romances like Amadís de Gaula:

These writings drove the poor knight out of his wits [. . .]. In short, he so buried himself in his books that he spent the nights reading from twilight till daybreak and

Library], 2003), pp. 740–53 (p. 740). All translations will be taken from this edition. See notably Jean-Luc Marion, Questions cartésiennes, vol. II. Sur l’égo et sur Dieu (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2002 [1996]), p. 129; also Etienne Gilson, Discours de la méthode. Texte et commentaire (Paris, Vrin, 1987), p. 98; Léon Brunschvicg, Descartes et Pascal lecteurs de Montaigne (Neuchatel: La Bacconière, 1945); Frédéric Brahami, ‘Pourquoi prenons-nous titre d’être? Pensée de soi et pensée de Dieu chez Montaigne et Descartes’, Revue de métaphysique et de morale, 49.1 (2006), pp. 21–39, and, more recently, the 2013 special collection of Montaigne Studies, entitled Montaigne and Descartes. Hervé Baudry sees fit to dismiss the connection in Le Dos de ses livres. Descartes a-t-il lu Montaigne? (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2015). Michael Moriarty provides a detailed reading of the echoes, themes, and strategies that link the two in ‘Montaigne and Descartes’, The Oxford Handbook of Montaigne, ed. Philippe Desain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 347–64. As he concludes there, ‘despite the radical difference between their methods of thought and the goals of their thinking, it is hard to conceive how Descartes could have cultivated his philosophy so successfully if Montaigne had not prepared the ground for him’ (p. 363).

23 As Denis Kambouchner notes, Descartes’s comments about history’s omission of the humble also recall Montaigne’s in ‘De la gloire’ (‘On Glory’): ‘Infinies belles actions se doivent perdre sans tesmoignage avant qu’il en vienne une à profit. On n’est pas tousjours sur le haut d’une bresche ou à la teste d’une armée, à la veuë de son general, comme sur un eschaffaut’ (II, 16, 622) (‘An infinity of fine actions must be lost without a witness before one appears to advantage. A man is not always at the top of a breach or at the head of an army, in sight of his general, as on a stage’; The Complete Works, p.573). ‘Descartes et le théâtre du monde’, Sapientia Veterum: Scritti di storia della filosofia dedicati a Marta Fattori, ed. Massimo L. Bianchi and Riccardo Pozzo with the collaboration of Samantha Maruzzella (Florence: Olschki, 2016), pp. 105‒17 (p. 111).

the days from dawn till dark; and so from little sleep and much reading, his brain dried up and he lost his wits.24

In September 1637, Constantijn Huygens has been reading the Discours.25 Selfdeprecatingly, he sends on a sample of his own work to Descartes:

Il m’est advis que je ne vous propose rien de plus difficile qu’une page de l’Amadis de Gaule, ou on m’a dit que vous souliez jeter les yeux. (AT I, 397)

It is my opinion that I propose to you nothing more difficult than a page of Amadís de Gaula, at which I am told you often throw a glance.26

In general, Descartes is using the Discours to look for a firmly practical reading encounter that will depart from the speculative stance of the schools (AT VI, 61‒2). Instead, it will mobilize and elevate simplicity, internal clarity, and good sense:

Ceux qui ont le raisonnement le plus fort, et qui digèrent le mieux leurs pensées afin de les rendre claires et intelligibles, peuvent toujours le mieux persuader ce qu’ils proposent, encore qu’ils ne parlassent que bas-breton, et qu’ils n’eussent jamais appris de rhétorique, et ceux qui ont les inventions les plus agréables et qui les savent exprimer avec le plus d’ornement et de douceur, ne laisseraient pas d’être les meilleurs poëtes, encore que l’art poétique leur fût inconnu. (AT VI, 7)

Those who reason the most powerfully and are the most successful at ordering their thoughts so as to make them clear and intelligible will always be best able to persuade others of what they say, even if they speak in the thickest of dialects and have never learned any rhetoric. And those whose linguistic expression is the most pleasing and who frame their thoughts in the most eloquent and agreeable way would always end up being the best poets, even if they did not know a single rule of poetic composition. (Discourse, p. 9)

He annuls any reliance on socially sanctioned models or the ‘rules’ of poetics. His quest for a new science is characterized by his keenness to rid himself entirely of (merely) plausible propositions, reliant as they are on opinion:

Considérant combien il peut y avoir de diverses opinions touchant une même matière, qui soient soutenues par des gens doctes, sans qu’il y en puisse avoir jamais plus d’une seule qui soit vraie, je réputais presque pour faux tout ce qui n’étoit que vraisemblable.

(AT VI, 8)

24 Cervantes, Don Quixote, trans. J.M. Cohen (Penguin: Harmondsworth, 1950), p. 32. The stories of the knight-errant Amadís de Gaula were first collected in 1465 and first published in 1508, with the first French translation in 1540. On the French reception, see Nicholas Paige, Before Fiction: The Ancien Régime of the Novel (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 2011), pp. 83–5. In different ways, Anthony Cascardi and Steven Nadler both take up the prompt to compare the predicaments of Don Quixote and Descartes’s sceptical persona in the Meditations: Cascardi, ‘Cervantes and Descartes on the Dream Argument’, Cervantes, 4 (1989), pp. 109–30 and Nadler, ‘Descartes’s Demon and the Madness of Don Quixote’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 58.1 (January 1997), pp. 41–55.

25 See his letter to Descartes of 18th September 1637 (AT I, 395).

26 This is the translation of Roger Ariew, in Erik-Jan Bos, Theo Verbeek, and Roger Ariew (eds), The Correspondence of René Descartes, New Critical Edition and Complete English Translation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming). I am very grateful to the editors for making this available in advance of publication.

Seeing how different learned men may defend different opinions on the same subject, without there ever being more than one which is true, I deemed anything that was no more than plausible to be false. (Discourse, p. 10)

Yet despite—or perhaps because of—this rejection of the ‘vraisemblable’ in science and metaphysics, Descartes remains fascinated by verisimilitude. It is not just that, in day-to-day life, we have to settle for doubtful opinions if nothing more certain is available. Descartes asks more searching questions, too: questions that define local literary-theoretical debates about plausibility. How do we get people to pay attention? How do we ward off their boredom, or impatience? How do we think about the benefits that their attention might bring them? In what ways should smooth continuance be disrupted? These questions bear upon the nature as much as upon the objects of attentive examination. Tracing out gradations of clarity and intelligibility, and taking for himself a field of study called something like ‘the human mind’, Descartes is also interested in what it might feel like to be attentive, and to tease judgement out of confused beliefs. Thus he tries to articulate the different actions performed by thought:

L’action de la pensée par laquelle on croit une chose étant différente de celle par laquelle on connaît qu’on la croit, elles sont souvent l’une sans l’autre. (AT, VI, 23)

The mental act by which we believe something, being different from that act by which we know that we believe it, often results in one act being present without the other.

(Discourse, p. 21)

DESCARTES’S LANGUAGE

The fact that Descartes is a keen observer of, and experimenter in, language has stimulated many existing studies of his rhetoric. The way that he rejects ‘rhetorical flavouring’, or ‘rhetorical pretences’ in favour of the simplicity of philosophical method may itself clearly be seen as a persuasive stance that shows an awareness of ‘audience demands and audience response’.27 Peter France makes the basic point that the whole of Descartes’s œuvre is a rhetorical enterprise, in the sense that, as we read the Discours or the Meditations, the Regulae or the Principles (not to mention the correspondence), we see an author who ‘attempts to set up a current of sympathy between himself and his reader’ (p. 58).

France is indebted, as he notes, to the work of Henri Gouhier, in La Pensée métaphysique de Descartes, and in particular to a chapter pithily entitled ‘Une philosophie sans rhétorique’ (‘A Philosophy without Rhetoric’). Gouhier in turn goes back to the immensely influential account of Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca and Chaïm Perelman, and their suggestion that we owe to the Discours de la méthode the collapse of any prestige attached to techniques of persuasion, thanks to that text’s preoccupation with the concept of evidence, available to anyone possessed of ‘bon

27 Replies to the Fifth Objections to the Meditations (MM 184). Peter France, Rhetoric and Truth in France: Descartes to Diderot (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972), p. 51.

sens’ or ‘good sense’.28 Reason, as the Regulae ad directionem ingenii tell us, needs to be guided from one evident truth to another.29 ‘Si la vérité est évidence’, asks Gouhier, ‘[. . .] comment s’imposerait-elle sinon par le seul éclat de cette évidence? (‘If the truth is evidence, [. . .] how could it impose itself other than through the light of that evidence alone?’ (p. 96).30 ‘Bon sens’, here, is a basic unit of understanding, equivalent to the basic form of communication that is the ‘bas-breton’ of the Discours (AT VI, 7). Thus Descartes rejects the discipline of rhetoric as taught in schools. But rhetoric is not the only disciplinary casualty of Descartes’s modernizing impulse. Dialectic, too—omnia Dialecticorum præcepta—is the object of suspicion, as it moves through smooth channels of logical reasoning without ever requiring a proper kind of attentiveness:

They [dialecticians] prescribe certain forms of reasoning in which the conclusions follow with such irresistible necessity that if our reason relies on them, even though it takes, as it were, a rest from considering a particular inference clearly and attentively, it can nevertheless draw a conclusion which is certain simply in virtue of the form. (rule 10, AT X, 405‒6)31

This proper kind of attentiveness is the fundamental object of Descartes’s new rules for the direction of the ingenium , as it is of his method and his philosophy in general. Descartes constantly appeals to the attentus lector (rule 12, AT X, 416). 32 We need to face head on any form of thought that enables us to avoid paying attention, and restore to it the presence of mind that it lacks: ‘We search carefully for everything which may help our mind to stay alert’ (rule 10, AT X, 406; CSM I, 36). Crucially, we can make the decision to cultivate our attentiveness through craft, or graft: ‘Craftsmen who engage in delicate operations, and are used to fixing their eyes on a single point, acquire through practice the ability to make perfect distinctions between things, however minute and delicate’ (rule 9, AT X, 401; CSM I, 33). Having developed our perspicacity at this level, we will ideally become capable of seeing how ‘all the sciences [ scientiæ ] are linked together’ (AT X, 215; CSM I, 3).

The discipline of dialectic screens or occults this kind of movement. It serves only to reformulate prior premises (premises which may well be faulty); thus, an art of expression, it is in fact akin to rhetoric:

28 Chaim Perelman et Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, La Nouvelle rhétorique: Traité de l’argumentation (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1958), pp. 3–4.

29 The Regulae were first published in a Dutch edition in 1684. On the controversial question of the dating of the text, see the edition of the Cambridge manuscript of the Rules for the Direction of the Ingenium by Michael Edwards and Richard Serjeantson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

30 ‘Le critère de l’évidence, que ce fût l’évidence personnelle du protestantisme, l’évidence rationnelle du cartésianisme ou l’évidence sensible des empiristes, ne pouvait que disqualifier la rhétorique.’ Chaïm Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, La Nouvelle rhétorique, p. 40. ‘The criterion of evidence, whether it was the personal evidence of protestantism, the rational evidence of Cartesianism or the sensory evidence of the empiricists, could only disqualify rhetoric.’

31 The translation is by Cottingham, Stoothoff, and Murdoch (eds), The Philosophical Writings of Descartes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), vol. I, p. 36, henceforth CSM I.

32 See in particular Geneviève Rodis-Lewis, L’Individualité chez Descartes, pp. 177–86 (p. 182).

Ordinary dialectic is of no use whatsoever to those who wish to investigate the truth of things. Its sole advantage is that it sometimes enables us to explain to others arguments which are already known. It should therefore be transferred from philosophy to rhetoric. (rule 10, AT X, 406; CSM I, 37)33

As long as participants in disputations are trying to win, they are more concerned to be persuasive than properly to weigh two sides of an argument (AT VI, 69; Discours, p. 56). Descartes’s preface to Picot’s 1647 translation of the 1644 Principles of Philosophy will confirm the suspicion of dialectic: his own logic is distinguished from

celle de l’Ecole qui n’est autre chose qu’une Dialectique qui enseigne les moyens de faire entendre à autrui les choses qu’on sait, ou même aussi de dire sans jugement plusieurs paroles touchant celles qu’on ne sait pas, et ainsi elle corrompt le bon sens plutôt qu’elle ne l’augmente. (AT IX, 13)

the logic of the Schools, for this is strictly speaking nothing but a dialectic which teaches ways of expounding to others what one already knows or even of holding forth without judgement about things one does not know. Such logic corrupts good sense rather than increasing it. (CSM I, 186)

Thus, writes Descartes in the same text, Je voudrais assurer ceux qui se défient trop de leurs forces, qu’il n’y a aucune chose en mes écrits qu’ils ne puissent entièrement entendre, s’ils prennent la peine de les examiner. (AT IX, 13; CSM I, 185)

I should like to assure those who are over-diffident about their powers that there is nothing in my writings which they are not capable of completely understanding provided they take the trouble to examine them.

Anyone can pay attention, but the effort of examination remains the precondition for success. Descartes’s tribute to Queen Christina of Sweden, who had encountered his work via Pierre Chanut, makes its fullest sense in this context:

Cette Princesse est bien plus créée à l’image de Dieu, que le reste des hommes, d’autant qu’elle peut étendre ses soins à plus grand nombre de diverses applications en même temps. Car il n’y a au monde que Dieu seul dont l’esprit ne se lasse point, et qui n’est pas moins exact à savoir le nombre de nos cheveux et à pourvoir jusques aux plus petits vermisseaux, qu’à mouvoir les cieux et les astres.

(To Chanut, 26th February 1649; AT V, 290)

This Princess has been created more closely in the image of God, than the rest of men, and especially in that she is able to extend her attentiveness to a greater range of different activities at the same time. For in the whole world there is only God whose mind never tires, and who is just as precise in knowing the number of hairs on our heads or in making provisions for even the tiniest worms as He is in moving the heavens and the stars.

33 Amidst this very rejection, Descartes is engaging with Aristotle’s own definition of rhetoric: ‘Rhetoric is a counterpart of Dialectic; for both have to do with matters that are in a manner within the cognizance of all men and are not confined to any special science’. Aristotle, The ‘Art’ of Rhetoric, trans. John Henry Freese (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Loeb], 1926), 1354a1–3.

Introduction

Christina has the rapt eye of a skilled craftswoman, but she can also master instabilities of scale, moving rapidly between intricate detail and overarching generality.

Descartes still needs to give form to his material, that it might encourage his reader to take this kind of trouble. The very premise behind Descartes’s rejection of education conventionally viewed, as we have already seen, is that he favours an alternative experience of learning: self-improvement, self-advancement, his own rules for the direction of the mind; and this pedagogical emphasis on ‘direction’ itself brings logical pressures to bear upon the notion that solipsism might be the defining condition of Cartesian personhood. For Henri Gouhier, ‘à son sommet, la nouvelle philosophie ne distingue plus recherche et enseignement’ (‘at its height, the new philosophy makes no distinction between searching and teaching’).34

John D. Lyons goes further: Descartes’s concern here goes beyond the establishing of a ‘current of sympathy’ between himself and the reader. Descartes ‘reconfigures the terms of the contract between the writer and the reader of philosophical works: he clearly intends to transmit certain concepts to his readers, but he seems even more to want to produce a transformation in those readers.’35

Descartes’s distrust of obscure or arcane language thus contributes to a strongly pedagogical stance. We need also to acknowledge, however, that Descartes’s basic emphases on methodical thinking and individual truth-seeking are also complicated by a rather sophisticated engagement with analogy, metaphor, and figures of speech, with the manipulation of ethos and example. Any overview of Descartes criticism will proffer analysis of the literary techniques he uses (his ‘poétique’, in a sense often granted in French), from the use of illustrative figures in the Regulae (‘I wish rather to clothe [this discipline] and adorn it so as to make it easier to present to the human mind’; rule 4, AT X, 374; CSM I, 17) to the constant domestic analogizing of Le Monde, the powders in jars, and the organ pipes in churches; from the metaphors and rhythm of the Discours and the Meditations to the dialogic dramatizations pitting honnête homme against pedantic scholar in La Recherche de la vérité.36

34 Gouhier, La Pensée métaphysique, p. 110. Gouhier is referring in particular to the Second Replies to the Objections: ‘Analysis shows the true path by which the thing was methodically discovered, as if a priori, so that, if the reader is willing to follow it and to pay sufficient attention to every point, he will understand it and assimilate it as perfectly as if he had discovered it himself’ (AT VII, 155; MM 99).

35 John D. Lyons, ‘The Cartesian Reader and the Methodic Subject’, L’Esprit créateur, 21.2 (summer 1981), pp. 37–47 (p. 43).

36 ‘Si vous mettez, par exemple, de la poudre en quelque vase, vous le secouez, et frappez contre [. . .]’ (‘ When you put powder in a jar, you shake the jar and tap it [. . .]’) (AT XI, 17; CSM I, 86); ‘Si vous avez jamais eu la curiosité de voir de près les orgues de nos églises [. .]’ (‘If you have ever had the curiosity to examine the organs in our churches [. . .]’; AT XI, 165; CSM I, 104). Le Monde or The World, Descartes’s first attempt to write a general treatise on physics, is dated to the winter of 1629–30; he suppresses it after Galileo Galilei is condemned in 1633 for stating that the earth moves around the sun, and not vice versa (in the Discours, Descartes will give a deliberately vague explanation of why he did not publish his earlier work on physics, omitting the name of Galileo). Le Monde is first published posthumously in 1664. The unfinished and undated Recherche de la vérité or Search for Truth was, like the Regulae, first published in a Dutch translation in 1684. See Frédéric Cossutta, ‘La métaphysique cartésienne au risque du dialogue philosophique. Schèmes spéculatifs, formes d’exposition et genres textuels dans le dialogue inachevé La Recherche de la vérité par la lumière naturelle’, Dix-septième siècle, 219.2 (2003), pp. 233–57.

Some figurative language, such as the metaphor of the ‘droit chemin’ or ‘straight’ or ‘right path’, provides continuity right across the work of Descartes, as he trains his own judgement that it may never be in doubt—‘In seeking the right path of truth we ought to concern ourselves only with objects which admit of as much certainty as the demonstrations of arithmetic and geometry’ (Regulae, rule 2, AT X, 366; CSM I, 12‒13)—and distances his own thought from that of his scholastic forebears:

Ce que les anciens en ont enseigné [des passions] est si peu de chose, et pour la plupart si peu croyable, que je ne puis avoir aucune espérance d’approcher de la vérité qu’en m’éloignant des chemins qu’ils ont suivis. (Les Passions de l’âme, art. 1, AT XI, 327‒8)

The ancients’ teaching on the subject [of the passions] is so slender, and for the most part so little believable, that I can have no hope of attaining truth except by departing from the paths they have followed. (Passions, p. 195)

Yesterday’s meditation, writes Descartes’s meditator in the second, led into a ‘deep whirlpool’ of doubt (AT VII, 24; MM 17). Today, he ‘will struggle on, and [. . .] try the same path again’. In the Recherche de la vérité, Descartes’s fellow-traveller is contrasted with those aimless folk who, having left ‘le grand chemin pour prendre la traverse’ (‘the main path to find a shortcut’), find themselves lost among briars and precipices (AT X 497; CSM II, 401).

In the Discours, in the course of elaborating his ‘morale par provision’, Descartes also contrasts his own circumspection with aimlessness:

Mais, comme un homme qui marche seul, et dans les ténèbres, je me résolus d’aller si lentement et d’user de tant de circonspection en toutes choses, que si je n’avançais que fort peu, je me garderais bien au moins de tomber. (AT VI, 16‒17)

But, like a man walking by himself in the dark, I took the decision to go slowly and to exercise such caution in everything that even if I made very little progress, I would at least be sure not to fall. (Discourse, p. 16)

He then mixes his metaphors to set the voyage alongside the process of building on firm ground:

Non que j’imitasse pour cela les sceptiques, qui ne doutent que pour douter, et affectent d’être toujours irrésolus: car au contraire, tout mon dessein ne tendait qu’à m’assurer, et à rejeter la terre mouvante et le sable pour trouver le roc ou l’argile. (AT VI, 29)

In doing this, I was not copying those sceptics who doubt for doubting’s sake, and pretend to be always unable to reach a decision; for, on the contrary, the aim of my whole plan was to reach certainty and reject shifting ground in the search for rock and clay. (Discourse, p. 25)

Doubt can now be traversed, with uncertainty put in the service of truth. If doubt is initially linked with the loss of all bearings, it can subsequently be mapped out.37

37 ‘The very act of positing certainty as a destination already puts the philosopher on firm ground and keeps him from slipping into a drift of aimless nomadism.’ Georges van der Abbele, ‘Cartesian Coordinates’, Travel as Metaphor from Montaigne to Rousseau (Minneapolis and Oxford, University of Minnesota Press, 1992), p. 43. Nathan Edelmann blurs the philological and the psychoanalytical, and