Structure, Function, and Diagnostic Approach to Skin Disease 1

Margaret A. Bobonich

Primary and nondermatology specialty care clinicians see the majority of patients with skin complaints on a daily basis. While patients make appointments to see their provider for a physical or blood pressure management, they commonly add an “Oh, by the way ” skin complaint. In contrast, many patients call the office or central scheduling and cite their reason for seeking treatment as a “rash.” This common, catch-all term reported by so many patients can leave the provider wondering what kind of eruption is really on the other side of the examination room door. Clinicians must be knowledgeable in evaluating skin lesions, which could range from skin cancer to a sexually transmitted infection.

Cutaneous lesions may represent more than just a skin disease and can be a manifestation of an underlying systemic process. Conversely, cutaneous conditions can cause systemic disease, dysfunction, and death. Psychosocial conditions can also be the cause or sequelae of skin conditions but are often negated. So in addition to maintaining competency in a primary specialty, clinicians need to acquire the essential knowledge and skills in dermatology—a daunting task given that there are almost 3,000 dermatology diagnoses.

The best approach for acquiring basic competency in the recognition and initial management of dermatologic disease (dermatoses) is to focus on conditions that are:

• High volume—the most common skin conditions seen in clinical practice;

• High morbidity—skin disease that is contagious or can impact quality of life or the community; and

• High mortality—life-threatening conditions that require prompt recognition.

This chapter outlines essential dermatology concepts, including anatomy and physiology, morphology of skin lesions and algorithmic approach for the assessment of any skin condition. This will enable clinicians to develop the knowledge and decision making skills for far more than the 50 most common skin conditions. Subsequent chapters provide a comprehensive review of hundreds of skin conditions that MUST be considered in a differential diagnosis, ensuring an accurate diagnosis and optimal patient outcome.

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

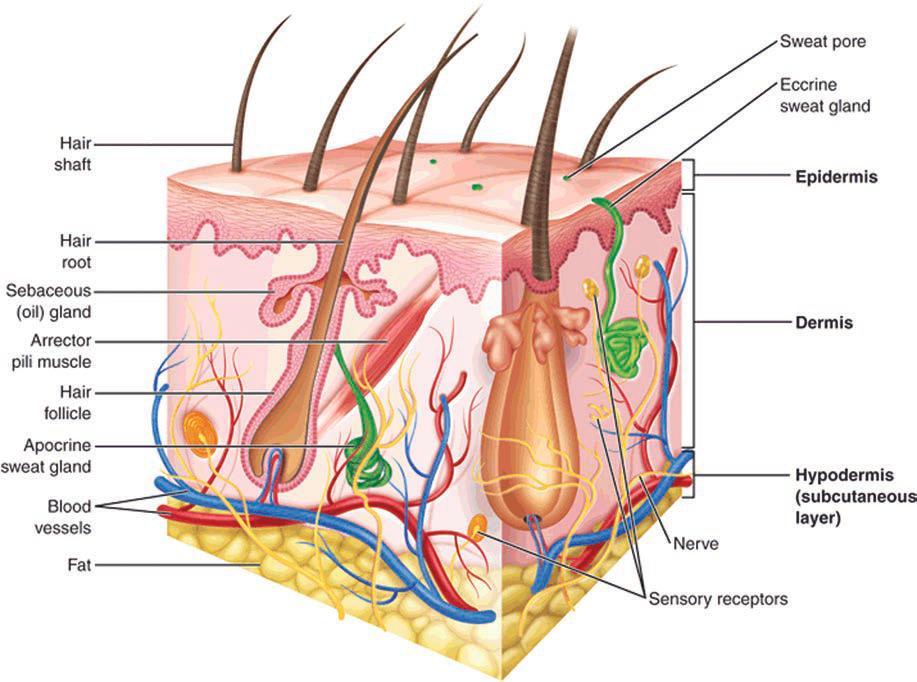

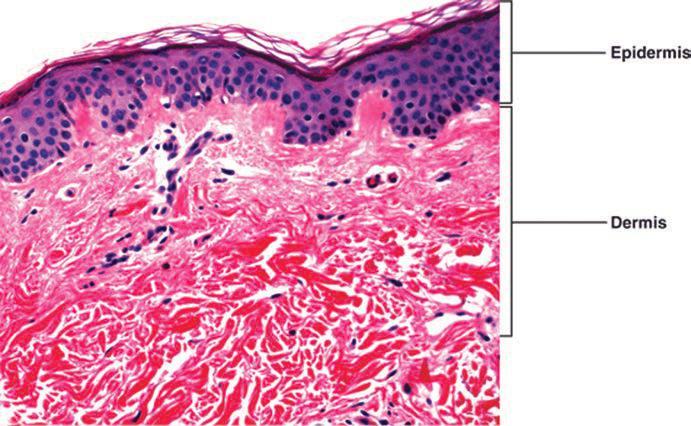

Understanding the normal structure and function of the skin enhances your ability to correlate clinical and histologic findings associated with skin lesions (Figure 1-1). The skin is not only the largest organ but also the most visible, allowing both patients and clinicians the opportunity to observe changes and symptoms.

The skin is complex and dynamic and provides a physical barrier against the environment; an innate and adaptive immunity that protects the body from pathogens; and thermoregulation. The skin is also responsible for vitamin D synthesis and protection from ultraviolet radiation on non-hair-bearing skin. It is a reservoir for medication administration and is a sensory organ (pain, pressure, itch, temperature,

touch). It comprises the epidermis, dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and adnexa or skin appendages and has regional variability in its thickness and structures. Glabrous skin does not have hair follicles or sebaceous glands, is located on the palms and soles, and is generally thick. In general, thin skin over the rest of the body houses a variable number of appendages, including the nails, hair, and sebaceous and sweat glands.

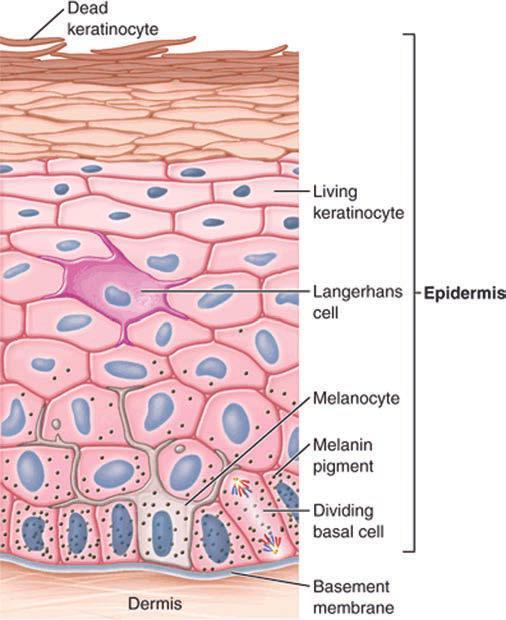

Epidermis

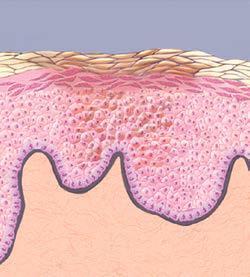

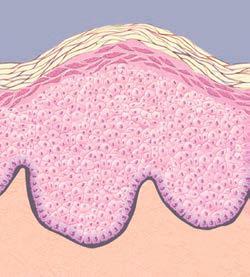

Commonly referred to as the “dead skin” layer, the epidermis is the locus of important structures and function (Figure 1-2). Cellular structures include keratinocytes, Langerhans cells, Merkel cells, and melanocytes. Nucleated keratinocytes differentiate as they ascend from the basal layer to the surface, filling with keratin and losing their nucleoproteins. Langerhans cells are intraepidermal macrophages responsible for phagocytosis of antigens and migration into the lymphatics and presentation to T cells. The immune function of the epidermis is paramount to our health. Merkel cells are believed to have a somatosensory function and are responsible for light touch and possible neuroendocrine function. Melanocytes synthesize the pigment which accounts for the variation in skin color among races. They are found in the dermis during fetal life and migrate to the basement membrane. The layers (strata) of the epidermis are responsible for protecting the body from the environment as both a mechanical and chemical barrier. Each strata has unique characteristics and functions (Table 1-1). Flattened keratinocytes with a thickened cell membrane create the stratified layer (shingles on a roof) in the stratum corneum, which is not capable of metabolic activity. This cornified layer saturated in a lipid complex provides a virtually impermeable barrier and minimizes water loss. Thus, any defect or impaired function of this layer can lead to pathologic changes and disease.

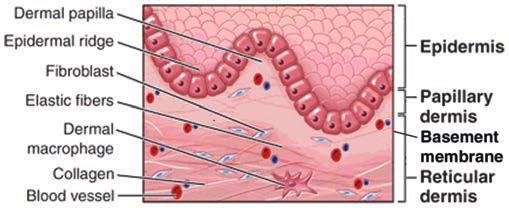

Dermis

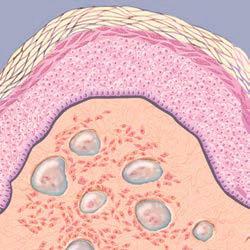

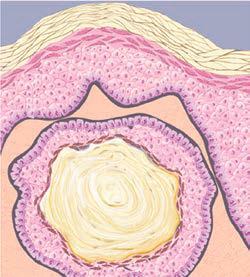

The dermis comprises fibroblasts, histiocytes, and mast cells, and is separated from the epidermis at the basement membrane (dermal–epidermal junction or DEJ). It adjoins with the papillary dermis (upper portion) Fibroblasts produce collagen (90% of the dermis), elastin, and ground substances, which comprise the majority of the dermis and are the supporting matrix of the skin (Figure 1-3). The dermis is also responsible for the continued immune response initiated in the epidermis by Langerhans cells, as well as neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and mast cells. Blood vessels, lymphatics, and sensory nerve endings for pain, itch, pressure, temperature, and touch are present. Arrector pili muscles in the dermis contract to make hair follicles stand up, creating the “goose bumps” effect. The reticular dermis (lower portion) joins with the subcutaneous or fat layer of the skin.

Subcutaneous Layer

The subcutaneous layer, also referred to as fatty tissue or hypodermis, comprises adipose cells and connective tissue, which varies in

1-1. Skin anatomy and histology. A: Anatomy of the skin. B: Corresponding photomicrograph of the skin showing the cellular distinction between the epidermis and dermis.

thickness according to the body location. The hypodermis provides a layer of protection for the body, thermoregulation, storage for metabolic energy, and mobility of the skin.

Adnexa

Adnexa or appendages of the skin include the hair, nails, and eccrine and apocrine glands. The structure of hair and nails is discussed in chapter 14.

Glands

Eccrine glands

Chiefly responsible for thermoregulation of the body, the eccrine or sweat glands are tubules that extend from the epidermis through the dermis and are triggered by thermal and emotional stimuli. Although they are diffusely spread over the body, most are located on the palms and soles, and can contribute to hyperhidrosis or

FIG.

1-2. Layers of the epidermis.

1-3. Dermis.

TABLE Strata of the epidermis 1-1

STRATUm (LAyER) CHARACTERISTIC

Corneum Brick and mortar layer

Lipid matrix and barrier Antimicrobial peptides

hypohidrosis. Eccrine glands maintain an important electrolyte and moisture balance of the palms and soles.

Apocrine glands

Found only in the axillae, external auditory canal, eyelids, mons pubis, anogenital surface, and areola, apocrine glands secrete a minute amount of an oily substance that is odorless. The role of these glands is not clearly understood.

ASSESSmENT OF THE SKIN

Clinicians should elicit a good patient history and perform a proper skin examination in order to generate a complete differential diagnosis.

History

Practitioners are afforded very limited time to assess, diagnose, treat, and document patient care. The patient history is sometimes slighted in view of time spent on the physical examination or patient education. However, the importance of an appropriate history relative to the skin complaint should not be overlooked. The history should begin with the patient’s general health and proceed with a focused or complete history relative to the skin complaint and presence of systemic symptoms (Box 1-1). Be aware that patients may be very cursory with details about their health history as they perceive that it is inconsequential to their skin condition. For example, a female seeking treatment for acne may fail to omit oral contraceptives on her medication list or her medical history of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Both can impact the clinician’s ability to adequately assess, diagnose, and manage her skin condition.

Medications are one of the most significant aspects of a history, receive the least attention, and yet have the greatest risk of impacting the patient’s skin condition. Medication history should not only include prescription drugs, but over-the-counter and illicit drugs, supplements, herbals, and “borrowed” medications. Chapter 17 provides tips on taking a medication history. The elderly and adolescents are known for sharing drugs and may be sheepish about admitting to it. NSAIDs are one of the most common causes of drug eruptions, but often omitted from their medication list. Oral contraceptives, which can have a significant impact on the skin, are commonly omitted from the patient’s list of medications.

FUNCTION

Mechanical protection; limits transepidermal water loss; limits penetration of pathogens (bacterial, viral, and fungal) or allergens

Lucidium Only on soles and palms protection

Granulosum

Keratin and fillagrin >80% of mass of epidermis profillagrin cleved into fillagrin, and loricin forming cornified envelop

Spinosum Lamellar granules (containing ceramides)

Langerhans cells

Basale

Cuboidal basal cells with nucleus and integrins

Scattered melanocytes

Found intracellularly in upper layer but migrate to corneum where most effect, responsible for lipid barrier function

Defends against microbial pathogens

Integrins responsible for adhesion to dermis

Initiation of keratinocyte differentiation

Migration upward to stratum corneum takes 2–4 wk

FIG.

FIG.

BOX 1-1 Complete History for the Assessment of Skin Lesions

Demographic Data

Age, sex, race—predilection in some diseases/conditions

Allergies

Drug, environmental, food (possible cross-reactivity)

medications

See chapter 17 (if drug-related eruption is suspected) prescription, over-the-counter, birth control, herbal supplements, illegal drugs

medical and Surgical History

personal (birth history for children), including skin cancer

Family (hereditary disease association or genodermatoses) pregnancy or lactation

History of Lesion or Eruption

Onset, circumstances, and duration

Spread and/or course of the skin condition

Aggravating or relieving factors

Associated symptoms—itching, pain, drainage, blisters, or odor previous episodes, treatment and response

Impact on sleep, eating, social activities, work, and school

Social History

Occupation and hobbies

Sunscreen use, tanning behaviors, and UVr exposure

Alcohol intake and smoking exposures (infectious or environmental)

Sexual behavior and orientation travel

Living conditions or household (especially important for infectious diseases)

Family structure

Psychological History

etiology or complication of skin conditions

Before concluding the history intake, it is recommended that clinicians inquire (an open-ended question) about any other specifics that the patient believes might be important about their skin condition. This invites communication and acknowledges the important role of the patient, family, and care givers in their patient-centered care. Patients may express grave concerns that their symptoms are similar to a disease discussed on a television talk show or health information discovered on an Internet search engine. Transparency in the patient’s perception and expectations at the beginning of the office visit will enable the clinician to personalize care for a better patient experience.

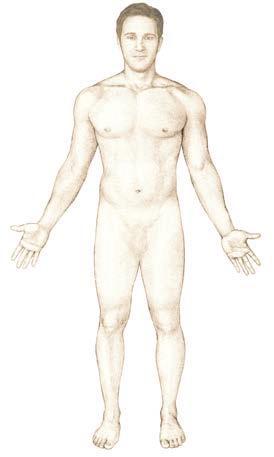

Physical Examination

Physical examination of the skin is a skill that is developed through repeated and systematic evaluations of your patients. The extent of the examination is determined by the patient’s symptoms and willingness to reveal their body. A complete skin examination is recommended for skin cancer screenings, with the patient completely disrobed and in a patient gown. It is also preferred for patients who come in with complaints of a skin eruption or those with systemic symptoms. In contrast, a focused examination from the waist up may be adequate for a chief complaint of acne that may require exposure

of the back and chest. Clinicians should encourage patients to allow maximum visualization for a thorough examination while respecting their modesty and rights to limit their physical exposure.

A helpful guide is provided to aid in developing a systematic approach for a skin examination for either the entire body or regional areas (Box 1-2). It is not necessary to wear gloves for a skin examination, allowing the clinician to use touch to optimize their assessment. All providers should clean their hands prior to and after examining a patient. Patients, and our society in general, have become increasingly aware of infection control and appreciate seeing the clinician cleanse their hands while in their presence. Yet, universal precautions should always be observed when preforming cutaneous procedures, exposed to body fluids, or examining skin that is not intact. They should also be worn when infection is suspected or touching the anogenital area and then immediately discarded.

Diagnostics

While the history and physical examination are the foundation for developing differential diagnosis, diagnostic tests may be necessary to rule out disease or support a definitive diagnosis. Each chapter in this text identifies recommended tests relative to the disease, and chapter 24 describes common procedures in detail. In-office diagnostic tools that can easily be used by nondermatology clinicians include the Wood’s light, KOH, or mineral prep. Diagnostic tests such as patch testing or tools such as dermoscopy should be reserved for dermatology clinicians trained in application and indications for practice.

One of the most important diagnostics used in the evaluation of cutaneous lesions is histopathology. Clinicians trained to perform shave and punch biopsies can send specimens for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, which provides microscopic analysis and reports on the pathologic changes in the skin. When indicated, immunohistology on patient tissue or sera utilizes various immunostaining techniques with light microscopy to identify antibodies. This is especially helpful in cutaneous manifestations with autoimmune diseases and is discussed in further detail in those chapters.

Clinicians should learn to competently interpret histopathology reports to ensure that clinicopathologic correlation exists, especially in inflammatory skin conditions. When there are questions regarding the report or interpretation, the clinician should discuss the biopsy with the pathologist. Most dermatology specialists send tissue biopsies to dermatopathologists who are specialty trained and board certified in dermatology with a fellowship in dermatopathology. They can provide a superior histologic analysis and opinion about possible diagnoses, especially when the clinician provides pertinent history, clinical findings, and their list of differential diagnoses.

ASSESSmENT OF SKIN LESIONS

Clinicians simply cannot know about every dermatosis, but they can develop assessment skills that will be the key to a timely and accurate diagnosis. Skin lesions can be described in a variety of ways and categorized by morphology, distribution, configuration, and arrangement. While some experienced dermatologists may use various approaches to diagnosis, these authors suggest that nondermatology and less experienced dermatology providers develop an algorithmic approach to diagnosis based on morphology of the primary lesion.

morphology

The characteristics or structure of a skin lesion is referred to as morphology. Once the clinician has identified the morphology of the primary lesion or eruption, they can generate a differential diagnoses.

BOX 1-2

Complete Skin Examination

How to Perform a Skin Examination

the two most important aspects of a complete skin examination are exposure and lighting.

patient must be properly gowned so that each part of the body can be visualized.

extra lighting may be needed for examination rooms without windows.

Always encourage the patient to undress completely; no peek-a-boo examinations!

Develop a systematic approach and use it for every skin examination. Begin with the patient seated in front of you and slightly lower.

Gently use your fingers to glide across the skin—your touch can identify lesions and comfort the patient.

Scalp

part the hair in various sections to visualize the scalp.

Look for papules, nodules, redness, scale, pustules, and scarring.

Hair

and Nails

Note hair color, pattern, and texture (see chapter 14).

Look for hair thinning or loss and patterns; note the presence/ absence of follicles.

Observe nails and periungual areas for discoloration, thickening, dystrophy, debris, or signs of infection. pigmented lesions can be found in unsuspecting places like beneath the nail.

Face

Get an overall view of the face.

Note the presence of scars and evidence of photodamage.

Look for redness, scaling, papules, pustules, comedones, skin tags, milia, keratoses, and pigmentation.

mouth

Look for any brown or red spots on the lips.

Dryness and scale on the lips in the elderly may be caused by photodamage.

Chapped lips in children or adolescents may be contact dermatitis. examine the mouth for lesions on the palate, buccal mucosa, and tongue.

patients on isotretinoin may have extreme dryness of facial skin and mucus membranes.

Eyes

examine the inner and outer canthi, orbital area, and lid margins for papules.

Note scale, erythema, or plaques in the brows or lids.

Check for erythema, erosions, or drainage of the conjunctiva.

Often, dermatology textbooks and online resources use a morphologybased approach to categorize diseases. Therefore, clinicians who lack the ability to correctly identify the morphology of the primary lesion must resort to fanning through the color atlas of dermatologic conditions, hoping that they will see a similar lesion or rash.

Primary lesions

The morphology of a primary skin lesion can provide important information about the depth of the process and the location of the

Ears

Look for scale or lesions on the helix

examine posterior earlobes for keloids and postauricular sulcus for redness and scale

Check conchal bowl for open comedones, hyperpigmented plaques, scale, and scarring

Nose

Look and feel the bridge, sides, creases, and nasal rims

Note telangiectasias, ulcerations, and abnormal pigmentation

Dilated blood vessels may signify sun exposure and possibly rosacea

Look for papules, pustules, and rhinophyma

Neck

Note the color, texture and distribution, especially anterior and lateral aspect, and inferior chin (photoprotected areas)

Trunk

Visualize the trunk with the patient sitting, standing, or lying down

Be sure to examine the buttocks, hips, and perianal area

If patients defer an examination of their genitals, inquire about new lesions or changes

Check the often forgotten umbilicus for psoriasis, nevi, and melanoma

Arms and Hands

Inspect arms separately and raise to inspect the axilla and lateral trunk

Look for discoloration or depigmentation in the axillae the antecubital fossa is a classic location for atopic eczema, whereas psoriasis and rheumatoid nodules favor the elbows. examine the dorsal and palmar surfaces of the hands, the fingers, and interdigital areas

Legs and Feet

examine the legs individually and thoroughly

Socks must be removed, to examine the feet, toes, and interdigital spaces

Don’t forget the plantar surface, which is a common place for pigmented lesions

Lymphadenopathy

Note occipital, posterior, and anterior cervical nodes with scalp lesions and infections

Check for regional and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, as well as hepatosplenomegaly, in patients with a history of melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma

Use all the tools available to assess the “ABCDe” of melanoma. If in doubt, ask for help or refer to a dermatology specialist.

pathology, that is, the epidermis, dermis, and/or subcutaneous tissue. A thorough understanding of the structure and function of the skin will then allow the clinician to envision the underlying pathologic process and assist in making the clinicopathologic correlation. Flat lesions often represent disease located in the epidermis, while raised lesions usually involve the dermis and/or subcutis. All clinicians should be able to identify these basic morphological types that provide the foundation for the assessment and diagnosis of any skin condition (Figure 1-4).

macule < 1 cm

Patch ≥ 1 cm

Flat, discoloration

Nodule < 1 cm

Tumor ≥ 1 cm

Solid, circumscribed, dermal

Papule < 1 cm

Plaque ≥ 1 cm

raised, solid, well-defined

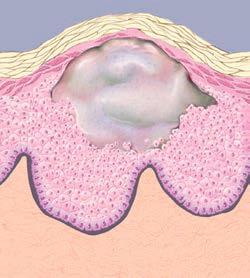

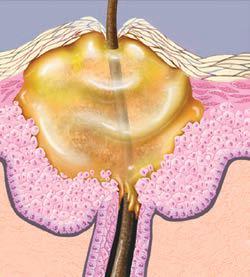

Cyst

Fluid/semisolid-filled nodule, maybe fluctuant

Vesicle < 1 cm

Bulla ≥ 1 cm

Fluid-filled, transparent

Fluid-filled, purulent

FIG. 1-4. Morphology of primary lesions.

Pustule

Secondary lesions

Secondary changes (scale, ulceration, lichenification, etc.) in the primary lesion can occur as the result of external factors, the process of healing, or complications from treatment (crusts, atrophy, purpura, scar, etc.). The characteristics of the secondary skin lesions provide further description (an adjective) about the primary lesion (noun). There are many descriptors, but several are commonly used in everyday practice (Figure 1-5).

Characteristics

The configuration of a lesion describes the shape, which can provide valuable clues. Annular plaques are characteristic of tinea and granuloma annulare. The arrangement is the location of lesions relative to each other. Lesions can be solitary, satellite (set apart from the body of the eruption), or clustered. While a red cherry angioma is typically a solitary lesion, the eruption of vesicles and pustules in herpes zoster is usually clustered and follows dermatomal arrangement.

Distribution

When observed, the distribution of skin lesions can provide valuable diagnostic clues. Lesions may be generalized or localized, or may favor particular areas of the body such as the interdigital spaces, acral areas, or mucous membranes. Many cutaneous and systemic diseases have hallmark clinical presentations based on the distribution of lesions (Figure 1-6). For example, lesions on the palms are characteristic of conditions like erythema multiforme, dyshidrotic eczema, secondary syphilis, and palmar-plantar psoriasis. Chronic scaly and erythematous patches or plaques on the extensor aspects of the extremities would favor a diagnosis of psoriasis compared to atopic dermatitis that usually affects the flexural surfaces. Care should be taken to note lesions involving the hair, nails, and mucous membrane which can be unique for some diseases. And lastly, the clinician should remember that the distribution of the lesions may change as a skin eruption progresses. Drug rashes typically start on the trunk and spread to the extremities (centrifugal). In contrast, erythema multiforme starts on the hands and feet, and advances to the trunk (centripetal).

Color

For most clinicians, the color of lesions is given little consideration and usually categorized as red or brown. But next time, take a closer look and use tangential lighting. Colors can provide insight into the underlying pathophysiology of the lesion. Red, purple, and blue lesions usually have a vascular etiology. Yellow and orange colors are typically the result of lipid, chemical, or protein deposition. Brown, black, and blue colors are associated with melanin or hemosiderin. White lesions can be associated with a lack of pigment and a “fleshcolor” lesion refers to the patient’s natural skin color.

Associated Symptoms

Symptoms such as pruritus, pain, and burning can be helpful in discerning a diagnosis. For example, pruritus is a classic symptom in urticaria compared to the burning sensation associated with angioedema. Other lesion symptoms reported may include

tenderness, drainage, and odor. Clinicians should always be alert to systemic symptoms that may have proceeded or accompanied the cutaneous lesions. This should prompt a complete review of systems and detailed physical examination. Most importantly, patients presenting with red flag symptoms warrant immediate referral for further evaluation and management. Red flag signs and symptoms are febrile patients with a rash; altered levels of consciousness; facial edema or angioedema; purpura; oral or ocular mucosal ulcerations; bullae with mucosal involvement; chest pain or dyspnea; positive Nikolsky sign; and erythroderma ( >80% body with erythema).

mORPHOLOGy-BASED APPROACH TO DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The foundation for a diagnosis of any skin lesion begins with a thorough history and physical examination. We suggest that the morphology of the primary lesion provide the first step in a systematic approach for generating a differential diagnosis. After the primary morphology is identified, the clinician can incorporate other lesion characteristics and associated findings to narrow the differential to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

Use of algorithms can be helpful (Figures 1-7 and 1-8). Algorithms are intended as adjunctive tools accompanied by critical thinking Once the category of dermatoses is identified, key characteristics such as distribution, associated symptoms, and diagnostics studies are used to rule out or support the final diagnosis. Tables 1-2 to 1-5 provide abbreviated lists of differential diagnoses, including the most common skin conditions seen in primary care. More extensive lists of differential diagnosis can be found online, manuals, or tools such as Habif’s Differential Diagnosis Deck (2012).

Ultimately, success with diagnostic tools like these algorithms requires routine use, good clinical judgment, and individualized patient care. Yet there are always uncommon diseases and atypical presentation that will challenge even the most experienced dermatology clinician. When the clinician is perplexed by the lesion or eruption, he or she should always consult with another experienced colleague or dermatology specialist.

CLINICAL PEARLS

j When there is a change in the surface of the skin, it usually indicates an epidermal process.

j Always perform a punch technique for the biopsy of any inflammatory lesion.

j Vesicles can be from an immune response or infectious process. pustules are most often associated with infection.

j Consider the possibility of immunosuppression in patients with chronic or recurrent skin infections or atypical presentations.

j pathologic processes occurring deep in the dermis or subcutaneous can leave the surface of the skin smooth but result in larger plaques that are not as circumscribed (wheals/hives compared to angioedema).

j Be aware of some of the great mimickers of skin disease: lupus erythematosus, tuberculosis (mycobacterium), cutaneous t-cell lymphoma, secondary syphilis, sarcoidosis, and amelanotic melanoma.

j Diffuse eruptions involving large BSA can overwhelm the clinician. Always start with the basics: the morphology of the primary lesion.

Annular round plaque with raised border and central clearing

Reticular Lacy or network-like pattern

Perifollicular Arising from hair follicles, papules

Pedunculate On a stalk or stem

1-5. Common characteristics of skin lesions.

Umbilicated

Central depression or dell

Linear Straight lines, like scratching

Guttate Small, red, separate tear drop

Filiform Finger-like projections

Targetoid “Iris” shape, concentric rings with central bull’s-eye

Nummular “Discoid” or coin-shaped plaque

Collarette ring of scale around border

Serpiginous Wavy or creeping

FIG.

Desquamation

Shedding or peeling of epidermis

Wheal or Hives

Circumscribed, flat-topped plaques lasting < 24 hr

Ulceration

Focal loss of epidermis and dermis

Purpura

palpable and nonpalpable extravasation of blood into tissues

Crust

Dried serum, often honey-color exudate

Angioedema

edema in the dermis and cutis, not well circumscribed

Excoriation

Neurotic type, irregular shape

Petechiae

Nonpalpable, extravasation of blood into tissues, <3 mm

morbilliform

Small macules, measles-like appearance, usually red

Fissure

Deep tears through the epidermis and into dermis

Excoriation

Linear wounds from scratching

Lichenification thickened, exaggerated lines

FIG. 1-5. Common characteristics of skin lesions (continued)

Extensor areasFlexural areasAcral Symmetrical

Spares anterior neck

If patient wears shorts

Photodistributed Bilateral, asymmetrical

1-6. DIStrIBUtION OF LeSIONS. Bilateral, present on both sides of the body. Symmetrical, same location on both sides. Zosteriform/herpetiform, along one or more dermatomes, unilateral. Acral, ears, nose, feet/soles, hands/palms. Seborrheic, hair-bearing, and sebaceous glands; scalp, forehead, moustache/ beard, and chest. Diffuse/generalized, scattered over large area; localized, specific to one particular area.

FIG.

Morphology of primary lesion

Fluid-fillled vesicle/bulla pustule cyst* (Table 1-2)

Clear fluid

Purulent

Pustular dermatoses

Vesiclular dermatoses

Bullous dermatoses

Solid macule/patch papule/plaque nodule/tumor

Color of lesion (Table 1-3)

Flesh/skin

Brown

White/ yellow

Red color

Go to Figure 1-8

Differential diagnosis lists Further examination of characteristics

FIG. 1-7. Morphology-based approach to diagnosis of skin lesions. *Semisolid material and often nodular.

TABLE Fluid-Filled Dermatoses 1-2

VESICLES

(<1 Cm)

Dyshidrotic eczema

herpes simplex

Impetigo

Varicella/zoster

tinea pedis

Scabies

Contact dermatitis

hand-foot-andmouth disease polymorphic light eruption

Grover disease

Arthropod assaults erythema multiforme

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Id reaction

BULLAE (≥1 Cm)

Bullous impetigo

Bullous tinea trauma/thermal

Bullous erythema multiforme

SSSS

SJS/teN

Autoimmune blistering disease

Bullous drug eruption

Lichen planus porphyria cutanea tarda

Diabetic bullae

PUSTULAR

Acne vulgaris rosacea

Drug-induced pustular

acne

Folliculitis–bacterial, candidiasis, pityrosporum

Scabies

pustular psoriasis (especially palmar-plantar)

perioral dermatitis

Subcorneal pustulosis

TABLE Lesions with Color 1-3

FLESH COLOR BROWN WHITE

Rough

Skin tags

Verruca

Open comedones

Actinic keratosis

Corns/callus

epidermal nevus

Smooth

Molluscum

contagiosum

Basal cell carcinoma

Verruca/hpV epidermoid cysts

Lipomas

Keloids/ hypertrophic scar

Granuloma annulare

Neurofibromas

pearly penile papules

Adnexal tumors

Freckles

Skin tags

Lentigines

Nevi (intradermal, compound, junctional)

Seborrheic keratosis

tinea versicolor (pinkish)

postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

erythrasma

Dermatofibroma

Café au lait

Mongolian spot

Melanoma pigmented basal cell

Dysplastic nevus

Congenital nevus

Fixed drug eruption (purple)

Becker nevus

pityriasis alba

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis

tinea versicolor

Ash leaf macule

Milia

Keratosis pilaris postinflammatory hypopigmentation

Nevus anemicus

Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma

Vitiligo

piebaldism

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

Morphea tuberous sclerosis

Yellow

Xanthelasma

Sebaceous hyperplasia

Necrobiosis

lipoidica

Morphea

SSSS, Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

SJS/teN, Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis.

hpV, human papilloma virus.

Red lesions

Scaly epidermis and possibly dermis pathology (Table 1-4)

Papulosquamous dermatoses no epidermal interruption

Eczematous dermatoses

epidermal interruption

Smooth dermal and/or subcutaneous pathology (Table 1-5)

Vascular reactions multiple lesions polymorphic

Inflammatory lesions solitary lesions monomorphic

FIG. 1-8. Morphology-based approach to diagnosis of red skin lesions.

T ABLE red and Scaly Dermatoses 1-4

ECZEmATOUS PAPULOSqUAmOUS

epithelial disruption, pruritus, and excoriations often prominent. Morphology may vary in acute and chronic stages.

Atopic dermatitis

Irritant contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis

Dyshidrotic eczema

Nummular eczema

Stasis dermatitis

Scabies

Secondary lesions (dermatitis herpetiformis, tinea, psoriasis, etc.)

Seborrheic dermatitis

polymorphic light eruption

Drug eruption

Lichen planus

Xerotic eczema

exfoliative erythroderma

T ABLE red and Smooth Lesions 1-5

Inflammatory lesions

Monomorphic (same size and shape), usually solitary

papules and dome-shaped

macules and papules

Arthropod assaults

Spider and cherry angiomas

Scabies

Acne

Keratosis pilaris

Candidiasis

pyogenic granulomas

Granuloma annulare

Viral exanthems

early psoriasis lesions

pityriasis rosea (w/o scale)

Secondary syphilis

pityriasis lichenoides

Grover disease

Nodules

Furuncles/carbuncles

epidermoid cysts

Cellulitis

erythema nodosum

Acne vulgaris

Mycosis fungoides

READINGS

No epithelial disruption, raised and scaly

Papules

pityriasis rosea

Keratosis pilaris

tinea

Lichen planus

Secondary syphilis

Guttate psoriasis

Prominent plaques

psoriasis

tinea

Lupus erythematosus

DLe

CtCL (mycosis fungoides) pityriasis rubra pilaris

Vascular reactions

polymorphic (varied size and shape)

Multiple, often confluent

Flat-topped

Transient rosacea

Urticaria

Persistent/blanchable

Kawasaki disease

SSSS

toxic shock syndrome

red man syndrome

Angioedema

Autoimmune blistering diseases

erythema multiforme

erythema nodosum

Drug eruption

Urticarial vasculitis

Ackerman, A. B. (1975). Structure and function of the skin. Section I. Development, morphology and physiology In S. L. Moschella, D. M. Pillsbury, & H. J. Hurley (Eds.), Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. Bolognia, J. L., Jorizzo, J. L., & Schaffer, J. Y. (2012). Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Purpuric/nonblanchable petechiae

Coagulation disorders

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis

henoch–Schönlein purpura

ecchymoses

Meningococcemia

rocky Mountain spotted fever

Vascular ulcers

Calonje, E., Brenn, T., & Lazar, A. (2012). McKee’s pathology of the skin (4th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Habif, T. P. (2012). Dermatology DDX deck (2nd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. Habif, T. P. (2009). Clinical dermatology (5th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. Lynch, P. J. (1994). Dermatology (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

CtCL, cutaneous t-cell lymphoma: DLe, Discoid lupus erythematosus.

CHAPTER

Corticosteroids and Topical Therapies 2

The skin is a large and complex organ that performs multiple functions allowing us to maintain a state of homogeneity. As a barrier, it protects against chemicals, microorganisms, ultraviolet radiation (UVR), and the loss of bodily fluids. It is a nutritive organ supplied by a network of superficial vessels that nourish and repair the skin. Constant vasodilation and constriction of blood vessels, along with the cooling response of sweat glands, accomplishes temperature regulation.

These functions can alter the moisture content in the skin and subsequently affect the penetration and efficacy of topical preparations. Percutaneous absorption (PCA) of topical treatments also varies depending on the thickness of the skin on different areas of the body. For instance, eyelid, antecubital, axillae, and genital skin are very thin and medication is quickly absorbed. The skin of the palms, soles, knees, and elbows is thicker, decreasing the rate of the absorption of medications applied. The presence or absence of occlusion also affects product permeability, rate, and potency of medications used.

This chapter will explore various topical formulations and the most appropriate use of each in the treatment of common dermatologic conditions. Sunscreens and their proper use will be presented, and an overview of botanical products will be outlined.

Systemic agents, specifically corticosteroids, are often used in dermatology, and we will review their optimum indications and usage. At times, oral agents may seem to be a more convenient option; however, topical therapies are often the better choice. With the correct usage of topical corticosteroid (TCS) therapies, side effects will be minimized.

SKIN HEALTH

Patients often ask about proper skin care. They are besieged with advertisements about the best and latest “miracle cream” and often believe that cost is equated with efficacy. For some, it is merely a factor of cosmesis, but many seek help because of uncomfortable and sometimes disfiguring skin conditions. Providing accurate information regarding product ingredients will help patients make better, more informed choices when faced with the myriad of options.

Cleansing

Everyone can benefit from a good skin care regimen. Recommendations regarding bathing and hand washing vary depending on a person’s age, activity, environment, culture, and skin condition. Cleansing the skin too often can contribute to worsening of certain skin conditions such as acne and eczema. The use of antibacterial soaps, abrasive materials, and gadgets are not necessary, and can be harmful to the skin by contributing to antibiotic resistance, irritation, or allergic reactions.

Environment

Protecting the skin from all types of weather is important. Sun, wind, cold, and humidity can hinder the skin’s protective function. In dryer climates, moisturizers should be applied within minutes of bathing to help prevent water evaporation and skin cracking, which can predispose patients with certain skin conditions to infection. Oil-free and noncomedogenic products are recommended for the skin of the face, while thicker moisturizers and those containing urea or lactic acid are more effective in treating hyperkeratotic skin commonly seen on the feet. Lactic acid, an α-hydroxy acid, is useful for softening dry, thick skin. This ingredient can also cause skin irritation and should not be used on delicate or inflamed skin.

In very cold climates, dry air from heating systems enhances water evaporation and contributes to the overall dryness of the skin. In humid climates, light-weight breathable clothing can help skin to remain dry. In all climates, sunscreen should be applied to exposed areas in the morning and reapplied every 2 hours when staying in the sun.

Healthy lifestyles also help maintain a person’s youthful skin appearance. Incorporating regular exercise, maintaining a proper diet, minimizing alcohol intake, and avoiding smoking and excessive stress are key factors in protecting the skin from aging prematurely.

Irritants and Allergens

Individuals with sensitive skin should choose products less likely to include common allergens such as fragrances, dyes, lanolin, propylene glycol, and parabens. If there is a suspected allergy, referral to a dermatologist can help the patient identify the allergens through patch testing (see chapter 3). Furthermore, dermatologists can provide patients with lists of personal hygiene products (a “safe” list) that they should avoid and those that are free of specific allergens. Patients are still warned to check the ingredient list of all products; even those on the safe list can change ingredients without any notice. Otherwise, primary care clinicians can provide some general guidance on widely available moisturizers that are free of the most common allergens (Table 2-1). Patients should be warned that the label “hypoallergenic” does not mean that the product does not contain common sensitizers. This is a marketing claim used by manufacturers and is not standardized or monitored. It only means that the product may cause fewer allergic reactions or has lower amounts of common sensitizers compared to other brands.

Yet not all dermatitis is caused by allergens. Frequent hand washing with soap and water is sometimes necessary, but can aggravate skin that is already affected by dermatitis. Hand dermatitis may be due to allergens in cleansers or irritation from the harsh chemical ingredients that can damage the epidermis and trigger inflammation. Water itself is the most common irritant in hand dermatitis and

Susan Busch and Gail Batissa Lenahan

TABLE Brand-Name Products Free of the Most Common Allergens* 2-1

CATEGORYPRODUCT†

Wipes7th Generation Free & Clear Baby Wipes

CleansersAveeno Baby Cleanser Moisturizing Wash

Eucerin Skin Calming Dry Skin Body Wash

Free & Clear Liquid Cleanser for Sensitive Skin

Vanicream Gentle Facial Cleanser

VML Hypoallergenics Essence Skin-Saving Clear & Natural Soap

Spring Cleaning Purifying Facial Wash for Oily Skin

MoisturizersAveeno Eczema Therapy Moisturizing Cream Baby

Eczema Therapy Moisturizing Cream

Cetaphil Oil Control Moisturizer SPF

Eucerin Professional Repair for Extremely Dry Skin

Lotion

Vaniply Ointment for Sensitive Skin

VML Hypoallergenics Red Better Daily Therapy

Moisturizer

LubricantsFragrance- and preservative-free: Aquaphor

Fragrance-, lanolin-, and preservative-free: white petrolatum or petroleum jelly

*Formaldehyde, fragrance (including botanicals), paraben mix/parabens, and propylene glycol.

†Retailers may sell old formulations of the brand. Manufacturers may change the formulation at any time and without warning or notice to consumers.

is often seen in health care workers. The use of a mild cleanser or a gel sanitizer made with at least 60% alcohol provides a less drying alternative. Alcohol gel sanitizers can prevent cracking and drying of the skin and should be used only on intact skin when hands are not visibly soiled.

TOPICAL THERAPIES

Moisturizers

Throughout this text, we will discuss skin conditions which involve, among other factors, a loss of the skin’s barrier function. When the skin is dry, the epidermis cannot perform its protective function, allowing microbes and allergens easy access to stimulate inflammation and/or infection. To maintain hydration and proper barrier function, the skin should be cleansed daily with lukewarm water and dried with a patting motion (not rubbed vigorously) to preserve the oils in the skin. Within 3 minutes of a shower or bath, a moisturizer or emollient should be applied to the entire body. This helps to “seal” in the water and increase moisture in the stratum corneum.

Moisturizer is a term commonly used when referring to any topical that is applied to treat dry skin. Products that are actually moisturizers hydrate the skin by drawing water into the stratum corneum through the use of humectants such as urea, glycerin, lactic acid, or glycolic acid. Emollients soften the skin and can offer a protective barrier with a layer of oil or another occlusive agent. Products may have one or both properties, and selection of the topical is an individual preference based on texture, odor, and location of the application. Moisturizers are available as ointments, creams, and lotions. Ointments offer the most hydration and greatest barrier and are especially effective for thick, dry, and scaly areas.

Moisturizers are also used for cosmetic purposes and can be applied several times a day, particularly after hand washing. Many

contain sunscreen, fragrances, alcohol, preservatives, and other chemicals mentioned above that are known to cause contact dermatitis. Patients with allergies should be instructed to apply the best agent for their dry skin but to avoid known agents that can trigger contact dermatitis.

Wet Dressings

When skin integrity has been altered and the skin becomes weepy or wet, several wet dressing options are available over the counter. Aluminum acetate powder (Domebero) is a medication that can be mixed with water for its antiseptic and drying properties. Acetic acid solution can be prepared by adding a half cup of household white vinegar to a pint of water for its bactericidal quality. Patients should be instructed to soak clean facecloths in the liquid and wring them out before placing on the weeping rash. These hypertonic treatments are effective in drying blisters and are commonly used for severe sunburns, poison ivy rashes, or moist intertrigo, but must only be used until the wet aspect of the condition has resolved.

Application is recommended two to four times per day for no longer than 30 to 60 minutes. Cool temperature water is used to decrease inflammation, while lukewarm water may be used to stimulate circulation in an infectious process.

In the pediatric population, especially those children with atopic dermatitis, plain wet dressings are recommended to help with the itch. In these cases, an emollient or TCS ointment (if prescribed) is applied first, followed by plain-water-soaked gauze, and covered with dry dressings or cotton pajamas and left on overnight. Wet dressings should never be occluded with plastic wrap as this increases the risk for maceration and increases bacterial growth.

Bleach Baths

Bleach baths can also be used for patients who are at higher risk for superficial skin infections. Patients with atopic dermatitis or recurrent skin and soft tissue infections from methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) can benefit from sitting in a warm bleach bath once to twice weekly for 10 minutes to reduce the bacteria count on their skin, and reduce the itching experienced by these patients. The bath is made from one quarter of a cup of unscented household bleach in a full bathtub. This dilutes the bleach to avoid any harmful effects. The skin is then treated with an emollient immediately after exiting the bath.

Cosmetic Botanicals

Clinicians are often asked about skin care products, specifically those containing natural ingredients (Table 2-2). There is some evidence to suggest that botanical products may be useful, but the scientific data are lacking. For patients with sensitive skin, eczema, atopic dermatitis, inflammatory or pruritic conditions, products containing feverfew, colloidal oatmeal, or sunflower seed oil may provide some soothing relief. Patients with rosacea and pigmented lesions may benefit from products containing licorice root extract, which has skin lightening and anti-inflammatory properties.

Botanical extracts are being used with increased frequency in the cosmetic industry, and the future of antiaging products, in particular, appears to be promising. Today many cosmetic formulations are made of botanical extracts and may improve the health, texture, and integrity of the skin, hair, and nails. Botanicals are also being used in cleansers, moisturizers, and astringents. Therefore, it is important to have an understanding of the expected benefit of these products.

Table 2-2 includes a synopsis of the more popular botanical ingredients used in skin care products today, but does not represent

TABLE Common Botanicals

NAME ORIGIN

Aloe Leaves of Aloe vera

Arnica Flowers of Arnica montana

CalendulaFlowers of Calendula officinalis (pot marigold)

Cayenne Fruit of Capsicum annuum

ChamomileDried flower heads and oil from Matricaria chamomilla

ChocolateSeeds of Theobroma cacao

DandelionLeaves, flowers, or root of Taraxacum officinale

EucalyptusLeaves, oil from Eucalyptus globulus

Feverfew Leaves, flowering tops of Tanacetum parthenium

Green TeaLeaves, buds from Camellia sinensis

Lavender Flowers, essential oil from Lavandula angustifolia

LemongrassLeaves, young stems, and oil of Cymbopogon citratus

Licorice root extract * Underground stem of Glycyrrhiza glabra

PatchouliLeaf, stem of Pogostemon cablin

ResveratrolSkin and seeds of grapes, berries, peanuts, and other foods

RosemaryLeaves, twigs from Rosmarinus officinalis

Soy Seeds from Glycine max

Tea tree oilLeaves from Melaleuca alternifolia

Witch hazelLeaves, bark, twigs of Hamamelis virginiana

EFFECT

Emollient, preventing infection

Anti-inflammatory

Antifungal, anti-inflammatory

Analgesic, warming stimulant

Antioxidant, antimicrobial, analgesic, anti-inflammatory

Antioxidant

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, possible antitumor activity

Antiseptic, astringent

Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-irritant, and anticancer properties. Orally, chewing leaves can cause ulceration and oral edema

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant

Fragrance, antimicrobial,antianxiety

Antiseptic, antibacterial, antifungal

antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral and antimicrobial

Antibacterial, antifungal

antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative agent

USE

Eczema, wound care, ringworm, burns, insect bites

Wound care, bruising, eczema, blisters (Avoid use on broken skin), acne, chapped lips

Radiation induced burns, decubitus ulcers, bruising

Neuropathic pain from shingles, massage oils, psoriasis

Wound care, burns

Cocoa butter for chapped skin, burns, irritants

Eczema, psoriasis, acne

Skin abscesses, minor wounds, bruises

Rosacea, antiaging, atopic dermatitis

Healing wounds and photoprotection

Fragrance, sleep inducer, sunburn, fungal infection, as rub form circulatory and rheumatic ailments

Athlete’s foot, ringworm

Skin lightening, healing for herpes blisters, canker sores, sunburn, insect bites

Eczema, seborrhea, acne, eczema, mosquito repellent

Antiaging, wrinkle reduction

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, analgesicSeborrhea, alopecia

Antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory

Skin lightening, improve skin elasticity, moisturizer

Antifungal, antimicrobial, anti-inflamamtoryAcne, onychomycosis, ringworm, dandruff eczema, insect bites

Astringent, antioxidant, anti-inflamamtoryAcne, contact dermatitis, bites, burns

*The oral form of licorice root extract can interact with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, aspirin, oral contraceptives, oral corticosteroids, diuretics, insulin, and stimulant laxatives.

Adapted from Foster, S., & Johnson, R. L. (2006). Desk reference to nature’s medicine. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society.

all botanicals on the market and is not an endorsement. Patients with skin disorders should always use caution before using any new topical products, as they may include ingredients that can cause contact dermatitis. Providers can guide patients away from allergens included in these products that can initiate an irritant or an allergic response, no matter how “natural” the ingredients.

CORTICOSTEROIDS

Corticosteroids play a significant role in the treatment of dermatologic disorders. The fact that they can be used topically, intralesionally, and systemically provides the clinician numerous options for patient management. Corticosteroids are a synthetic derivative of the natural steroid, cortisol, which is produced by the adrenal cortex. There are two types of corticosteroids, glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. Glucocorticoids are the drugs most often used in dermatology and will be the focus of discussion in this chapter. In general, regardless of the method of administration, these drugs act as anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and antiproliferative agents. When they are used topically, their vasoconstrictive properties determine their potency, and they are used to treat a wide range of disorders from acute allergic dermatitis to chronic immunobullous disorders. We will look more closely at these frequently used medications in the next two sections and will discuss their mode of administration, indications, and side effects and will make recommendations for use depending on the severity of the disorder.

Topical Corticosteroids

Many conditions seen in primary care and dermatology can be appropriately treated with a TCS. They penetrate the skin and work by decreasing the inflammatory pathways that cause the skin to become red and inflamed. Within days of use, however, the production of new skin cells is suppressed, creating the risk of atrophy and striae with long-term usage. The following factors can have an effect on treatment success and should be considered when prescribing any topical medication.

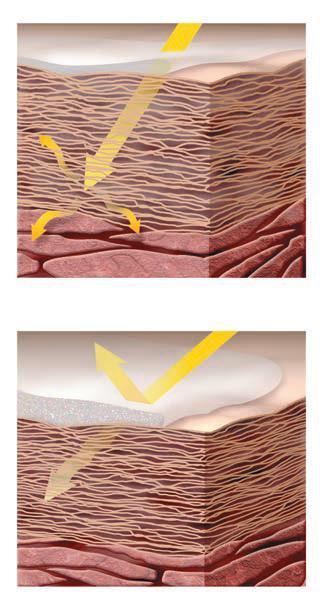

Percutaneous absorption

The ability of a topical medication to be effective is dependent on the transdermal delivery of the active ingredients from the stratum corneum of the epidermis to the underlying capillaries. There are many variables which can promote or impede PCA, including drug concentration, frequency of administration, occlusion, surface area involved, the vehicle, age and weight of patient, location on the body, and amount of time the topical is left on the skin. PCA is increased with hydrated (moist) skin, heat or elevated temperature, and the condition of skin barrier.

Vehicles

Topical agents are prepared in a variety of vehicles or bases that constitute the inactive portion of the medication, allowing the drug to be delivered into or through the skin (Table 2-3). Generic formulations of TCS may vary in the contents of the vehicle. Contact allergies may worsen if a generic product is substituted for a brand-name prescription. Vehicles can also alter the potency of the corticosteroid itself, which is why a drug may be class 1 in an ointment form but a different class in a cream or lotion vehicle. Additionally, consistency of the vehicle can be important.

Strength/frequency

A concentration of 1% indicates 1 g of drug will be contained in 100 g of the formulation. Efficacy of a topically applied drug is usually

TABLE Vehicles for Topical Preparations 2-3

VEHICLEDEFINITION

SolutionHomogenous mixture of two or more substances

LotionLiquid preparation, thicker than solution

Likely to contain oil, water, and/or alcohol

CreamThicker than lotion Requires preservatives to extend shelf life Greater potential for allergic reactions

OintmentSemisolid, mostly water-free

Petrolatum-based product Spreads easily, penetrates better than creams

GelAqueous, semisolid emulsion

Liquefies when in contact with skin

FoamLiquid comprised of oil, solvents, and water packaged under pressure in aluminum cans

SprayLiquid dispensed through an aerosol container or atomizer

PREFERENCES

Excellent for scalp/ hair-bearing areas

Lotions spread easily. Use in large areas

Use when skin is moist or exudative. Can be used in any area

Well tolerated

Choose when skin is dry or for increased penetration (thick skin). Messy in hairy areas

Great for hairy areas

Avoid on blistered skin, may sting

Great for scalp and thick plaques

Penetrates well without mess

Helpful for hard to reach places

And scalp or hairy areas

not proportionate to the concentration. Doubling or halving the concentration often has a surprisingly modest effect on the response. Occlusion increases the penetration and ultimately the effectiveness of the product. Compounding of proprietary products with other ingredients may alter the stability of the drugs and should be done with caution if at all.

The common recommendation is to use the least potent TCS that is effective; however, using a TCS that is too weak may be ineffective and decrease compliance and patient confidence in the provider. Low-potency corticosteroid preparations can be used safely when needed on thinner skin. The common risks that apply to all TCS still exist when overused.

Ultrapotent or high-potency TCS should be used on a rotation schedule, with two or three daily applications for a 2-week period, followed by 1 or 2 weeks without TCS. Some clinicians advocate use of nonsteroidal agents or emollients during this break period. Paradoxically, stronger TCS (groups I and II) are commonly used in skin disorders such as lichen sclerosis and lichen planus that may involve mucosal skin without concern for atrophy.

Side effects

Common side effects with TCS or their vehicle’s include contact dermatitis, acne-like eruptions, skin atrophy, hypopigmentation, telangiectasia, purpura, and striae, as well as ocular effects of increased

intraocular pressure, cataract formation, and glaucoma. When using corticosteroids under occlusion, there is also a risk for folliculitis and maceration of the skin. In addition to patient education, providers can help reduce these risks by ordering only enough medication to achieve clearing. Refills may be given; however, follow-up appointments should be provided. Prescriptions given to poorly compliant patients should not be refilled indefinitely, and nonsteroidal alternatives may be a better option for some individuals.

Due to variability in generic formulations and the common addition of propylene glycol, a common allergen, allergic reactions from TCS can be a conundrum. If a corticosteroid allergy is suspected, desoximetasone ointment 0.05% is the treatment of choice until the allergen is confirmed. Referral to dermatology can identify specific allergens through patch testing with Thin-layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous Test (TRUE Test). This company has recently added tixocortol pivalate and budesonide, which can help identify TCS allergies. These products are widely used in dermatology and allergy practices. Testing for propylene glycol, however, requires a more comprehensive patch series such as the North American Series, which is usually provided only at larger academic or occupationally focused clinics. Any patient who is not improving on TCS should be reevaluated, and the provider should consider the following:

• Contact dermatitis due to the corticosteroid or preservative in the corticosteroid;

• Noncompliance;

• Tachyphylaxis (a decrease in the pharmacologic response after repeated administration of a topical agent); and

• Incorrect diagnosis: alternate diagnoses to consider include but are not limited to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, drug reaction, or fungal infection.

Atrophy or thinning of the skin from the application of TCS can occur within a fairly short period of time with potentially permanent results. Atrophy can be manifested by fragile skin and stretch marks (Figure 2-1). Labeling on the tubes of TCS rather than on their outer boxes may help patients follow instructions on how much and where medications are to be applied, thereby reinforcing instructions given during the office visit.

Superficial staphylococcal folliculitis is a possible side effect of TCS, especially when using with occlusion. If noticed early, this can sometimes be reversed by drying out the skin with aluminum acetate compresses (i.e., Dombero); however, folliculitis often requires oral antibiotics to clear.

Adrenal suppression is a possible side effect of the stronger TCS, especially if used on a large surface area. This side effect is generally

TABLE Estimated Amounts for Topical Medication 2-4

Conversions: Adult: 30 g covers entire adult body in one application; children: ½ of the adult amount; infants (6–12 months): only ¼ of the adult amount; 1 FTU = 0.5 g per application.

FTU, fingertip unit.

reversible and frequently associated with long-term oral corticosteroid therapy.

Avascular necrosis (AVN) is another very rare side effect that can be caused by either topical or systemic corticosteroids. AVN has been documented with long-term use of TCS. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hip may be ordered in the investigation of AVN symptoms, which include pain in the groin, hip, buttock, or knee that increases with activity and is relieved with rest.

Quantity

How much medication is needed to achieve the desired effect is always a question (Table 2-4). The fingertip unit (FTU) and rule of hand are two measurements used to determine how much product is needed and how much to prescribe. The FTU is the amount of topical medication that comes out of a tube with a 5 mm diameter and covers the area from the distal crease of the forefinger to the ventral aspect of an adult fingertip (Figure 2-2). For an adult, 2.5 FTU is needed to cover the entire neck and face. For a child (ages 1–5), one half of this amount would be needed to cover the same area. For an infant, quarter of the adult amount would be sufficient. One FTU

FIG. 2-1. Steroid atrophy.

FIG. 2-2. Fingertip units.

weighs approximately 0.5 g. Therefore, an adult face and neck would require a 35-g tube of cream for a 2-week course of treatment. The “rule of hand” describes the area to be treated. An area the size of four adult hands (including the digits) can be treated with 1 g of ointment or two FTU.

Occlusion

For increased penetration of very thick skin plaques or to treat a full body rash, occlusion may be used for a period of 2 hours twice daily. Medication is applied, and plastic wrap is used to cover the entire area where it is practical, such as an arm or leg. Alternatively, corticosteroid-impregnated tape such as Cordran Tape is available and useful for small, thickened areas. If the entire body surface is involved, a plastic suit, known as a sauna suit, can be worn for a few hours in the day after applying the corticosteroid to all areas. Occlusive plastic suits are inexpensive and can be found at most sporting goods stores.

Brand versus generic

Insurance companies often require that providers use generic in place of brand-name topical preparations. While generic products contain the same active ingredient, the product’s vehicle often differs, altering the efficacy of the drug as well as contributing to the induction of contact dermatitis. The choice of a generic versus a brand-name drug is dependent on many patient-specific factors, but is often unfortunately determined by the insurance company’s formulary.

Combination drugs

Commercially prepared TCS may be combined with drugs from a different class such as antifungal or antiyeast agents and are not generally recommended by dermatologist. They may provide some symptomatic relief, but may obscure the correct diagnosis. In addition, they can promote development of microbial resistance to antibiotics and may increase sensitization to ingredients. TCS have been successfully paired, however, with a vitamin D analog, calcipotriene (Dovonex, Vectical), in the treatment of psoriasis. Likewise, acne preparations are often combined, offer ease of use, and assist with the compliance of the younger patient.

Patient education and follow-up

The patient’s ability and willingness to comprehend and comply with treatment recommendations can be influenced by a variety of factors, including the patient’s relationship with their provider, the belief that the treatment will work, comprehension of directions provided, financial or time constraints, as well as the cosmetic elegance, or “feel” of the prescribed products. Patients are more likely to adhere to simple dosing schedules. It is helpful to provide them with clear verbal and written instructions.

Acne patients should be advised to avoid skin trauma by using minimal friction when cleansing skin and avoiding picking at their skin. When discussing topical retinoids, providers should refer to a “pea-sized” dab for the correct amount to apply to the face. Using the demonstration of a pea-sized emollient cream during an office visit may help patients better understand application instructions. For patients with psoriasis, demonstrating the application of emollients into thickened plaques can increase compliance and prescription efficacy. Recommending that all patients bring remaining tubes of products to their follow-up visits can help determine usage. Providers can consider creative options for patients to help them follow the agreed upon treatment plan. Smart phone features such as alarms and calendars can remind patients when to use their medications and return for follow-up appointments.

Systemic Corticosteroids

Many providers of dermatology services are extremely comfortable managing patients on TCS. It is instinctual to choose the proper dose, vehicle, and quantity for the patient. Those same practitioners, however, are far less comfortable when the patient requires additional and specifically systemic therapy. While there are numerous conditions which respond well to systemic corticosteroids and in fact may be essential, fear of side effects and rebound disease prevail. Oral administration usually takes preference over the intramuscular (IM) route although IM injection guarantees the proper dose and can be helpful if gastrointestinal side effects exist.

Systemic corticosteroids are classified as short, intermediate, and long acting. Prednisone, which is the corticosteroid of choice in dermatology, is an intermediate acting medication. Prednisone is actually the inactive form of the drug and must be converted to the active form, prednisolone, by the liver. It is generally given as a single daily, oral dose because it most closely approximates the body’s natural diurnal variation. Divided doses are generally reserved for acute, lifethreatening conditions and in general have an increased effect despite the same total daily dosage. In liver impaired patients, prednisolone is the drug of choice. The length of a treatment course depends entirely on the condition. In acute dermatoses such as contact dermatitis, a short 2- to 3-week tapering course or “burst” is suggested. In severe conditions which will require more than 4 weeks of treatment, an alternate day dosing schedule can be used. Once the skin condition has cleared, the dose will be carefully decreased in increments until the patient maintains improvement on a minimal dose.

Prednisone dosing

There are little data in the literature comparing or recommending the duration of therapy for corticosteroid use, and many practitioners are confused by the correct way to prescribe and taper the corticosteroids when needed. For example, when treating allergic contact dermatitis with oral corticosteroids, many experienced clinicians will treat with 40 to 60 mg per day for 2 weeks and will discontinue without taper. The risk involved with short-course therapy is rebound of the condition and not adrenal suppression. Some clinicians experienced in treating a widespread contact dermatitis for an adult prescribe prednisone 20 to 60 mg daily (depending on the extensiveness of rash and patient’s weight) for 7 days followed by a tapering dose for an additional 7 to 14 days.

If the rash affects more than 20% of the body surface area, oral prednisone at a dose of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day for 7 days is given, then the dose may be reduced by 50% in the next 5 to 7 days and then tapered and discontinued over the following 2 weeks (Basow, 2013). See Box 2-1 for considerations in systemic corticosteroid selection and Table 2-5 for corticosteroid tapering suggestions.

BOX 2-1 Considerations for Systemic Corticosteroid Selection

Age and weight of patient

Comorbidities: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, peptic ulcer disease, osteoporosis

Systemic infections: fungal

Short term (2–3 weeks) versus long term (months)

Need for vitamin D and calcium supplementation

Biphosphonates if on oral corticosteroids for more than 4 weeks

Known hypersensitivities

Drug interactions

Frequency of dosing: b.i.d. dosing has a more potent effect than QD dosing but should only be used for acute therapy of life-threatening illness.

TABLE Prednisone Taper Suggestions (Alternative to Medrol Pack) 2-5

DURATION OF TAPER DOSE AND AMOUNTPATIENT INSTRUCTIONS*

2 wk in decreasing daily doses 5-mg tabs, dispense #114

3 wk 10-mg tabs, dispense #70

4 wk (simplified)10-mg tabs, dispense #70

Day 1: Take 14 pills (70 mg), then decrease by 1 pill each day for 14 days

Week 1: 6 tabs QAM

Week 2: 3 tabs QAM

Week 3: 1 tab QAM

Week 1: 4 tabs QAM

Week 2: 3 tabs QAM

Week 3: 2 tabs QAM

Week 4: 1 tab QAM

Note: Calculations based on dosing 0.5–1 mg/kg for 150-lb (68 kg) adult.

*In addition to dosing, patient instructions should include: “To avoid recurrence of symptoms, do not stop taking pills without being instructed by your provider.”

Side effects

Side effects associated with oral corticosteroid therapy are usually dose and duration dependent. Some preexisting conditions are associated with increased risk, including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure, cataracts or glaucoma, peptic ulcer disease, concurrent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, presence of infection, low bone density, and osteoporosis.

Consider the patient’s risk of fracture when prescribing oral prednisone. Bone loss is a serious, potential side effect of glucocorticoid therapy and needs to be monitored closely. To minimize bone loss, the following general principles should be kept in mind:

• The glucocorticoid dose and duration of therapy should be as low as possible.

• Topical therapy is preferred over systemic and should be used whenever possible.

• Weight-bearing exercises are recommended to prevent bone loss.

• Patients should avoid excess alcohol and smoking.

The American College of Rheumatology Task Force Osteoporosis Guidelines offer suggestions for patients taking any dose of glucocorticoids for greater than 3 months:

• Patients should maintain a total calcium intake of 1,200 mg per day and vitamin D intake of 800 IU per day through either diet and/or supplements.

• Bisphosphonates may be added based on the individual risks, which include gender, age, and fracture risk especially if the course of corticosteroids is intended for several months.

• Bone mineral density (BMD) testing is recommended at the initiation of glucocorticoid therapy and after 1 year for patients receiving any dose of glucocorticoids for greater than 3 months.

Avascular necrosis is a rare side effect that can be caused by either topical or systemic corticosteroids. As mentioned in the TCS section, a MRI scan may be ordered in the investigation of AVN symptoms. Patients should be advised that should signs and symptoms of AVN develop they should call their medical provider immediately.

Patient education and follow-up

When prescribing systemic corticosteroids, clinicians should educate patients for maximum outcomes and minimal side effects:

• Take prednisone with food.

• b.i.d. dosing will have a more potent effect than once per day dosing, but is not recommended for short-term treatment.

• Taking prednisone early in the morning helps diminish the possible side effects of hyperactivity or sleep disruption and decreases risk of adrenal suppression.

• Patients should be advised against stopping prednisone dosing abruptly and to continue medication until the entire taper course is complete to prevent rebound dermatitis.

All patients on long-term oral corticosteroids should be monitored for elevated blood sugar, hypertension, and weight gain after 1 month and then every 2 to 3 months. Complaints of eye pain, blurry vision, or halos may be indicative of increased intraocular pressures, and patient suffering from these complaints should be seen by an ophthalmologist. The provider should be most cautious in prescribing prednisone to patients who have the comorbidities of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity or to those who abuse alcohol or tobacco as these patients are already at high risk for developing infections, ulcers, and glaucoma. As long-term prednisone use is also associated with possible gastrointestinal perforation, an upper gastrointestinal series may be ordered if the patient has a history of peptic ulcer disease.

Patients who are on long-term prednisone therapy should be seen at least every 1 to 2 months for evaluation and more frequently if symptoms of possible complications arise. Close monitoring for possible side effects may be done in collaboration with the patient’s dermatologist.

Special Considerations

Corticosteroids in pregnancy

Practitioners will inevitably encounter pregnant women in their practice and must be familiar with medication safety when providing care to this group of patients. Prescribing medication during pregnancy can be particularly challenging given the insufficient data and research on the safety of medications during this period. Some skin conditions of the pregnant woman require topical and systemic treatment. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy categories (Table 2-6) should always be considered.

Topical corticosteroids. During pregnancy, women are generally advised to avoid the TCS treatments that they have come to rely on during flares. In general, topical medications are often considered first-line therapy for most; however, there are times when systemic agents may be more appropriate.

The data on the effects of TCS used during pregnancy are limited; however, the current available data on the safety of mildto-moderate TCS during pregnancy suggest a lack of association between their use by the mother and oral clefts, preterm delivery and fetal death as previously postulated. Therefore, the following recommendations for TCS use in the pregnant patient are as follows:

• Mild- to moderate-potency TCS should be preferred to more potent corticosteroids during pregnancy.

• Potent to very potent TCS should be used as second-line therapy for as short a time as possible.

• There is a small risk for fetal growth restriction when using potent/ very potent TCS during pregnancy.

• There is a theoretically higher risk of adverse events with use of TCS when used in high-absorption areas such as eyelids, genitals, and flexures.

Systemic corticosteroids. There are limited data on the potential teratogenic effects on the fetus, mainly because of the ethical issues

TABLE FDA Pregnancy Categories 2-6

CATEGORY DEFINITION

A Adequate and well-controlled studies have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus in the first trimester of pregnancy, and there is no evidence of risk in later trimesters.

B Animal reproduction studies have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus, and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women.

C Animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect on the fetus, and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans, but potential benefits may warrant use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks.

D There is positive evidence of human fetal risk based on adverse reaction data from investigational or marketing experience or studies in humans, but potential benefits may warrant use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks.

X Studies in animals or humans have demonstrated fetal abnormalities, and/or there is positive evidence of human fetal risk based on adverse reaction data from investigational or marketing experience, and the risks involved in use of the drug in pregnant women clearly outweigh potential benefits.

involved in testing corticosteroids drugs in pregnancy. As mentioned previously, TCS are often considered the first line of therapy; however, when topical agents aren’t enough, the provider and patient must weigh the risk versus benefit of oral agents.

With oral glucocorticosteroids, there is a potential for increased risk of premature rupture of the membranes (PROM) and intrauterine growth restriction. There may also be an increased risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, osteoporosis, and infection. They should be avoided during the first trimester when the hard palate is forming. When necessary, the lowest effective dose should be used.

Glucocorticosteroids are excreted in breast milk, but their use during lactation is deemed compatible by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) if justified by the potential benefit to the health of the mother. An alternative is to discard the breast milk for the first 4 hours following ingestion of a dose of prednisone >20 mg.

CLINICAL PEARLS

j Avoid prescribing Lotrisone for diaper dermatitis. The high potency TCS in this product is not FDA approved for children and is too strong for the diaper area. In addition, the antifungal is too weak to be effective.

j When prescribing a potent or ultrapotent corticosteroid, patients should not use more than one 45-g tube per week. Pharmacists will not usually refill ahead of time, so calculate correctly for best results.

j The popular and conveniently packaged Medrol dose pack (methylprednisolone) is an insufficient short-term remedy that tends to prolong patients’ suffering due to rebound flaring.

j Mild- to moderate-strength TCS appear to be safe during pregnancy for short-term use. Avoid high-potency TCS if possible, especially during the first trimester. If high-potency corticosteroids are needed, as always, they should be used for the shortest amount of time.

ULTRAVIOLET LIGHT

Photobiology