1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

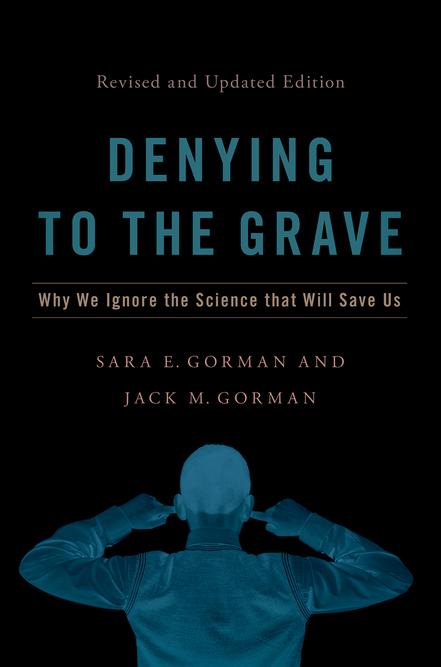

Names: Gorman, Sara E., editor. | Gorman, Jack M., editor. Title: Denying to the grave : why we ignore the science that will save us / Sara E. Gorman and Jack M. Gorman, [editors].

Description: Revised and updated edition. | New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Previous edition entered under: Sara E. Gorman. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020054636 (print) | LCCN 2020054637 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197547458 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197547472 (epub) | ISBN 9780197547489 (Digital-Online)

Subjects: LCSH: Social medicine. | Science— Methodology. | Skepticism. | Belief and doubt (Psychology) | Denial (Psychology)

Classification: LCC RA418 .G64 2021 (print) | LCC RA418 (ebook) | DDC 362.1— dc23

LC record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2020054636

LC ebook record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2020054637

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197547458.001.0001

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

In memory of Howard Kantor, tireless devotee of science and medicine, beloved father, grandfather, and husband and of Kate Gorman, beloved mother, grandmother, and great grandmother.

Author’s Note ix Acknowledgments xi

Introduction: Science Denial Comes of Age 1

one Conspiracy Theories 39

two Charismatic Leaders 77 three Confirmation Bias 125

four Causality and Filling the Ignorance Gap 163

five Avoidance of Complexity 195

six Risk Perception and Probability 237

seven Science Denial in Crisis 277

eight The Attack on Health and Science Institutions 303 Conclusion 333

Authors’ Note

The information in this book is not intended to replace the advice of the reader’s own physician or other medical professional. You should consult a medical professional in matters relating to your health, especially if you have existing medical conditions, and before starting, stopping, or changing the dose of any medication you are taking. Individual readers are solely responsible for their own healthcare decisions. The authors and the publisher do not accept responsibility for any adverse effects individuals may claim to experience, whether directly or indirectly, from the information contained in this book.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the wonderful, inspiring people who helped us write this book. First and foremost, we thank all of the brilliant scholars and medical and public health practitioners, without whose contributions to our growing body of knowledge about neuroscience, psychology, and health decision-making this book would have been impossible to write. We’d like to thank in particular the following scholars, who all generously served as interlocutors at some stage during the writing of this book: Daniel Kahneman, Michael Shermer, Seth Mnookin, Tal Gross, Kate Starbird, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Howard Neukrug, Yochai Benkler, and Nicoli Nattrass. We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers of the book whose input was critical in shaping and improving our final product. We are indebted to the wonderful people at Oxford University Press, including our fantastic editor, Sarah Harrington, whose sharp insight was always much appreciated.

Sara would also like to thank her colleagues and mentors at work for allowing her the time and flexibility to work on the book and for supporting and encouraging her along the way.

Many people provided intellectual and emotional support to Jack that was indispensable in writing this book, and he is especially grateful to Colin Leinster, Richard Munich, Catherine DiDesidero, Amy

Monahan, Dionne Monsanto, Fletcher Harper, Bruce Brady, Rabbi Avi Weiss, Rabbi Steven Exler, Alexandra Roth-Kahn, Stan Arkow, Cindy Aaronson, Marc and Harriet Suvall, Gary and Jamie Gordon, Ben and Barbara Zucker, Joel Einlinger, Miriam Westheimer, Carol Clayton, Leigh Steiner, and David Bressman for their creative ideas and friendship.

We would like to thank our wonderful Critica team, starting with David Scales, a great physician, scholar, moral compass, and friend and including Cody Leff, Catherine DiDesidero, Cindy Goldstein, and Peter DiCaprio.

Finally, there are many amazing people in our personal lives who have offered us critical support as we undertook this journey. Because we are father and daughter, we have most of them in common. We are deeply grateful to Rachel Moster, Sara’s sister and Jack’s daughter, and David Moster, Rachel’s husband, for being our all-time champions, for always being there for us, and for always sharing our excitement with their overwhelming warmth, intellectual prowess, and zest.

We wrote this book with the people of the future in mind, who face the consequences of the climate crisis and all the other mistakes our generations make. They need all of us to embrace the scientific realities of what we are doing and should be doing immediately. In particular, we think with love of Jack’s three grandchildren, Hannah Beth Moster, Jonah Moster, and Raphael Kohen, who is also Sara’s son.

Two people are the bedrock and inspiration for all we do. Lauren Kantor Gorman, Sara’s mother and Jack’s wife, is the beacon of light in the madness that sometimes comes from writing a book. As a brilliant psychiatrist, she has wonderful insights into the emotional basis for people’s choices and decisions that helped us enormously in focusing our own ideas. We thank her for always being so steady, reliable, and smart, and for showering us with her constant love and warmth. Last but by no means least, we’d like to thank Robert Kohen, Sara’s husband and Jack’s son-in-law. Robert is our brilliant interlocutor, our intellectual companion, and our unending inspiration. Thank you for being you.

Science Denial Comes of Age

ON OCTOBER 8, 2014, THOMAS ERIC DUNCAN DIED IN A Dallas hospital from Ebola virus infection. From the moment he was diagnosed with Ebola newspapers all over the country blared the news that the first case of Ebola in the United States had occurred. Blame for his death was immediately assigned to the hospital that cared for him and to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1 By the end of the month a total of four cases had developed in the United States: two in people—including Duncan, who acquired it in African countries where the disease was epidemic— and two in nurses who cared for Duncan. Headlines about Ebola continued to dominate the pages of American newspapers throughout the month, warning of the risk we now faced of this deadly disease. These media reports were frightening and caused some people to wonder if it was safe to send their children to school or ride on public transportation— even if they lived miles from any of the four cases. “There are reports of kids being pulled out of schools and even some school closings,” reported Dean Baker in the Huffington Post. “People in many areas are not going to work and others are driving cars rather than taking mass transit because they

fear catching Ebola from fellow passengers. There are also reports of people staying away from stores, restaurants, and other public places.”2 An elementary school in Maine suspended a teacher because she stayed in a hotel in Dallas that is 9.5 miles away from the hospital where two nurses contracted the virus.3 As Charles Blow put it in his New York Times column, “We aren’t battling a virus in this country as much as a mania, one whipped up by reactionary politicians and irresponsible media.”4

It turns out that Thomas Duncan was not the only person who died in the United States on October 8, 2014. If we extrapolate from national annual figures, we can say that on that day almost 7,000 people died in the United States. About half of them died of either heart disease or cancer; 331 from accidents, of which automobile accidents are the most common; and 105 by suicide.5 About 80 people were killed by gunshot wounds the day that Thomas Eric Duncan died, two thirds of which were self-inflicted. National Public Radio correspondent Michaeleen Doucleff made a rough calculation and determined that the risk of contracting Ebola in the United States was 1 in 13.3 million, far less than the risk of dying in a plane crash, from a bee sting, by being struck by lightning, or being attacked by a shark.6 The chance of being killed in a car crash is about 1,500 times greater than the risk of getting infected with the Ebola virus in the United States.

It probably comes as no surprise that there were very few frontpage headlines about bee stings or shark attacks on October 8, 2014, let alone about car crashes and gun violence. Perhaps this seems natural. After all, Ebola virus infection, the cause of Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is unusual in the United States, whereas heart attacks, cancer, car crashes, suicide, and murder happen on a regular basis. The problem, however, with the media emphasizing (and ordinary people fearing) Ebola over other far more prevalent health threats is that it shapes our behavior, sometimes in dangerous ways. How many people smoked a cigarette or consumed a sugary breakfast cereal while reading about the threat they faced in catching Ebola? Some Americans jumped on the blame-game bandwagon, attacking the CDC, insisting that politicians and hospitals had dropped the ball and accusing African countries of ignorant, superstitious behavior. In Washington, DC, one quarter of the members of Trinity

Episcopal Church stopped attending services because they feared that some fellow parishioners might have traveled to West Africa.7 An Ohio bridal shop owner reported losing tens of thousands of dollars because Amber Vinson, one of two Dallas-based nurses who tested positive for Ebola, had visited her shop. The owner closed the store during the incubation period and had the store professionally cleaned, but “a string of frightened customers canceled their orders.”8 According to a presidential commission report, “Americans focused on their own almost nonexistent risk of catching Ebola from travelers instead of pressing to help the truly affected nations.”9 It is quite likely that most of these frightened Americans did not increase their exercise, cut down on eating processed foods, fasten their seat belts, quit smoking, make sure guns in the home were unloaded in locked cases, or get help for depression and alcoholism. The novelty of Ebola was exciting, like watching a horror movie. Those other causes of death are familiar and boring. In other words, Americans acted in an irrational way, overestimating the risk of Ebola and underestimating the risk of the life-threatening phenomena about which they might be able to do something. As Sara pointed out in an article she wrote that month, “What is the most effective treatment for Americans to protect themselves from early death by an infectious pathogen? A flu shot.”10

Fast forward to the spring and summer of 2020 in America. A new pathogen had taken the nation by storm. SARS CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, was spreading across the country with few signs of slowing any time soon. By August, the illness had already sickened almost 6 million people and killed more than 180,000 in the United States. And yet, unlike the unnecessary fear that arose from the 2014 Ebola epidemic, in the case of the novel coronavirus, all across the country people were insisting that the crisis was not real, that it was either exaggerated or, worse, fabricated as part of an elaborate conspiracy. Chief among those who believed that COVID-19 was an exaggerated, perhaps even fake, threat was none other than the president of the United States himself, Donald Trump. At one point, Trump accused Democrats of politicizing the virus, even calling it “their new hoax.”11 All the while, important guidelines around social distancing and mask-wearing were not being followed by large parts of the population, states such as Florida that should have been

on lockdown continued to keep everything open, and even schools opened in the midst of this out-of-control spread of the virus. At the same time, the president and his supporters championed unproven treatments, such as hydroxychloroquine.

These two examples—Ebola and COVID-19—represent two different forms of science denial that we will address in this book. On the one hand, in the case of Ebola, we saw skewed risk perception that caused people to become irrationally afraid of something that was not a major threat. On the other hand, in the case of COVID-19, we see a complex meeting place of group identities and conspiratorial thinking that resulted in a downplaying of a real threat. Both of these forms of science denial drive scientists, healthcare experts, and public health officials nuts and, in some cases, may put people at real risk. Time after time, we make decisions about the health of ourselves and our families based on emotion rather than on analysis of the scientific data. The government uses taxpayer money to mount hugely expensive studies to prove that the science is correct, but people come up with more and more reasons to insist that the research is incomplete, biased, or simply wrong. Opposing camps accuse each other of deliberately plotting to harm the American public, of being bought off by special interests, and of stupidity. The data may be clear about who is right and who is wrong, but people make decisions that ignore or deny the evidence. This book is an attempt to elucidate why we do this and what we can do to make better decisions about our health and the health of our loved ones.

Why Do We Ignore or Deny Scientific Evidence?

It turns out that there are many reasons for refusing to acknowledge scientific evidence when making health decisions, but stupidity is not one of them. Very smart people take positions that are not remotely based on evidence. There is a direct relationship, for example, between intelligence and refusing to vaccinate a child: this unfortunate behavior is championed mainly by very well-educated and affluent people.12 What then causes smart people to make decisions and adopt positions that have no factual basis? That is the question with which this book wrestles.

The idea for this book took shape as Sara became increasingly involved in the world of public health. She was particularly mystified by the “anti-vaxxers,” people who promulgate the notion that immunizations are harmful, causing, among other things, autism. Nothing could be further from the truth. Immunization is one of the triumphs of modern medicine, having eliminated from our lives deadly diseases such as smallpox, measles, polio, and diphtheria. It is based on elegant scientific principles, has a remarkable safety record, and absolutely does not cause autism. How could anyone, Sara wondered, refuse to vaccinate a child?

At the same time Jack, who trained as a psychiatrist and worked as a scientist most of his career, was increasingly interested in the reasons people own guns. He thought at first it was for hunting and decided that just because it was a hobby that neither he nor any of his New York City friends pursued, it would be wrong to advocate that all the people who enjoy shooting animals in the woods be prevented from doing so. But a look at the data showed that a relatively small number of Americans are hunters and that most gun owners have weapons for “protection.” Yet studies show over and over again that a gun in the house is far more likely to be used to injure or kill someone who lives there than to kill an intruder. Gun availability is clearly linked to elevated risk for both homicide and suicide.13 Statistically speaking, the risks of having a gun at home are far greater than any possible benefits. Consider the tragic case of 26-year-old St. Louis resident Becca Campbell, who bought a gun reportedly to protect herself and her two daughters. Instead of protecting herself and her family from risks such as the Ferguson riots, she wound up accidentally shooting and killing herself with it.14 The first edition of this book focused on these and other cases of science denial came out in 2016. Months later, Donald Trump was elected president of the United States and a whole new era of science denial began. Denialism and conspiracy theories multiplied. The truth became harder and harder to discern. Our trust in scientific agencies began to erode even further. When COVID-19 emerged and, along with that, more conspiratorial thinking and ever more rampant science denial, we knew an update to this book was needed. At the end of this introduction, we will detail exactly what updates we have made.

In many cases scientific evidence strongly suggests a position— such as vaccinate your child and don’t keep a gun at home— that many of us choose to ignore or deny. We make a distinction between “ignore” and “deny,” the former indicating that a person does not know the scientific evidence and the latter that they do but actively disagree with it. We quickly generated a list of several other health and healthcare beliefs that fly directly in the face of scientific evidence and that are supported by at least a substantial minority of people:

• Vaccination is harmful.

• Guns in the house will protect residents from armed intruders.

• Foods containing genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are dangerous to human health.

• The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is not the cause of AIDS.

• Nuclear power is more dangerous than power derived from burning fossil fuels.

• Antibiotics are effective in treating viral infections.

• Unpasteurized milk is safe and contains beneficial nutrients that are destroyed by the pasteurization process.

• Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT, sometimes referred to as shock treatment) causes brain damage and is ineffective.

• Climate change is not real and is not caused by humans.

• COVID-19 is a hoax and a conspiracy, and mask-wearing does not protect against the virus.

• Tap water in most communities is loaded with toxic substances and unsafe to drink.

Throughout this book we present evidence that none of these positions is correct. But our aim is not to exhaustively analyze scientific data and studies. Many other sources review in rigorous detail the evidence that counters each of these nine beliefs. Rather, our task is to try to understand why reasonably intelligent and well-meaning people believe them.

Many of the thought processes that allow us to be human, to have empathy, to function in society, and to survive as a species from an evolutionary standpoint can lead us astray when applied to what

scientists refer to as scientific reasoning. Why? For starters, scientific reasoning is difficult for many people to accept because it precludes the ability to make positive statements with certainty. Scientific reasoning, rather, works by setting up hypotheses to be knocked down, makes great demands before causality can be demonstrated, and involves populations instead of individuals. In other words, in science we can never be 100% sure. We can only be very close to totally sure. This runs counter to the ways we humans are accustomed to thinking. Moreover, science works through a series of negations and disproving, while we are wired to resist changing our minds too easily. As a result, a multitude of completely healthy and normal psychological processes can conspire to make us prone to errors in scientific and medical thinking, leading to decisions that adversely affect our health.

These poor health decisions often involve adopting risky behaviors, including refusal to be vaccinated, consumption of unhealthy food, cigarette smoking, failure to adhere to a medication regimen, and failure to practice safe sex. We believe that these risk-taking behaviors stem in large part from complex psychological factors that often have known biological underpinnings. In this book we explore the psychology and neurobiology of poor health decisions and irrational health beliefs, arguing that in many cases the psychological impulses under discussion are adaptive (meaning they evolved to keep us safe and healthy) but are often applied in a maladaptive way. We also argue that without proper knowledge of the psychological and biological underpinnings of irrational health decisions and beliefs, we as a society cannot design any strategy that will alleviate the problem. We therefore conclude by offering our own method of combating poor health decision-making, a method that takes into account psychology and neurobiology and that offers guidance on how to encourage people to adopt a more scientific viewpoint without discounting or trying to eliminate their valuable emotional responses.

We will assert many times that the problem is not simply lack of information, although that can be a factor. Irrational behavior occurs even when we know and understand all the facts. Given what we now understand about brain function, it is probably not even appropriate to label science denial as, strictly speaking, “irrational.” Rather, it is for the most part a product of the way our minds work. This means

that simple education is not going to be sufficient to reverse science denial. Certainly, angry harangues at the “stupidity” of science denialists will only reify these attitudes. Take, for example, an article in The Atlantic that discussed affluent Los Angeles parents who refuse to have their children vaccinated, concluding, “Wealth enables these people to hire fringe pediatricians who will coddle their irrational beliefs. But it doesn’t entitle them to threaten an entire city’s children with terrifying, 19th-century diseases for no reason.”15 This stance is unhelpful because it attempts to shame people into changing their beliefs and behaviors, a strategy that rarely works when it comes to health and medicine. As Canadian scientists Chantal Pouliot and Julie Godbout point out in their excellent article on public science education, when scientists think about communicating with nonscientists, they generally operate from the “knowledge deficit” model, the idea that nonscientists simply lack the facts. Evidence shows, these authors argue instead, that nonscientists are in fact capable of understanding “both the complexity of research and the uncertainties accompanying many technological and scientific developments.”16 Pouliot and Godbout call for educating scientists about social scientists’ research findings that show the public is indeed capable of grasping scientific concepts.

Six of the chapters of this book examine single key drivers of science denial. Two new chapters apply these drivers to new science denial phenomena that have arisen since 2016: the government’s assault on science and misinformation and science denial specifically around COVID-19 and other health crises. All of the chapters rest on a combination of psychological, behavioral, sociological, political, and neurobiological components. We do not insist that these are the only reasons for science denial, but through our own work and research we have come to believe that they are among the most important and the most prominent.

Just Because You’re Paranoid Doesn’t Mean People Aren’t Conspiring Against You

In chapter 1, “Conspiracy Theories,” we address the complicated topic of conspiracy theories. Complicated because a conspiracy theory is not prima facie wrong, and indeed there have been many conspiracies

that we would have been better off uncovering when they first occurred. Yet one of the hallmarks of false scientific beliefs is the claim by their adherents that they are the victims of profiteering, deceit, and cover-ups by conglomerates variously composed of large corporations, government regulatory agencies, the media, and professional medical societies. The trick is to figure out if the false ones can be readily separated from those in which there may be some truth.

Only by carefully analyzing a number of such conspiracy theories and their adherents does it become possible to offer some guidelines as to which are most obviously incorrect. More important for our purposes, we explore the psychology of conspiracy theory adherence. What do people get out of believing in false conspiracy theories? How does membership in a group of like-minded conspiracy theorists develop, and why is it so hard to persuade people that they are wrong? As is the case with every reason we give in this book for adherence to false scientific ideas, belittling people who come to believe in false conspiracy theories as ignorant or mean-spirited is perhaps the surest route to reinforcing an anti-science position.

Charismatic Leaders

Perhaps the biggest and most formidable opponents to rational understanding and acceptance of scientific evidence in the health field are what are known as charismatic leaders, our second factor in promoting science denial. In chapter 2, “Charismatic Leaders,” we give several profiles of leaders of anti-science movements and try to locate common denominators among them. We stress that most people who hold incorrect ideas about health and deny scientific evidence are well-meaning individuals who believe that they are doing the right thing for themselves and their families. We also stress that the very same mental mechanisms that we use to generate incorrect ideas about scientific issues often have an evolutionary basis, can be helpful and healthy in many circumstances, and may even make us empathic individuals.

When we deal with charismatic figures, however, we are often dealing with people for whom it is difficult to generate kind words. Although they may be true believers, most of them are people who should know better, who often distort the truth, and who may

masquerade as selfless but in fact gain considerable personal benefit from promulgating false ideas. And, most important, what they do harms people.

There is a fascinating, albeit at times a bit frightening, psychology behind the appeal of these charismatic leaders that may help us be more successful in neutralizing their hold over others. Although many of them have impressive-sounding academic credentials, the factors that can make them seem believable may be as trivial as having a deep voice.17 Chapter 2 marks the end of a two-chapter focus on the psychology of groups and how it fosters anti-science beliefs.

If I Thought It Once, It Must Be True

Everyone looks for patterns in the environment. Once we find them and if they seem to explain things, we become more and more convinced we need them. The ancients who thought the sun revolved around the earth were not stupid, nor were they entirely ruled by religious dogma that humans must be at the center of the earth. In fact, if you look up in the sky, that is at first what seems to be happening. After years of observation and calculation, the Greek astronomer Ptolemy devised a complicated mathematical system to explain the rotation of stars around the earth. It is not a simple explanation but rather the work of a brilliant mind using all of the tools available to him. Of course, it happens to be wrong. But once it was written down and taught to other astronomers, it became hard to give up. Rather, as new observations came in that may have challenged the “geocentric” model, astronomers were apt to do everything possible to fit them into the “earth as the center of the universe” idea. That is, they saw what they believed.

It took another set of geniuses— Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo— and new inventions like the telescope to finally dislodge the Ptolemaic model.

Once any such belief system is in place, it becomes the beneficiary of what is known as the confirmation bias. Paul Slovic captured the essence of confirmation bias, the subject of chapter 3, very well:

It would be comforting to believe that polarized positions would respond to informational and educational programs. Unfortunately, psychological research demonstrates that people’s beliefs change

slowly and are extraordinarily persistent in the face of contrary evidence. Once formed, initial impressions tend to structure the way that subsequent evidence is interpreted. New evidence appears reliable and informative if it is consistent with one’s initial beliefs; contrary evidence is dismissed as unreliable, erroneous or unrepresentative.18

Does this sound familiar? We can probably all think of examples in our lives in which we saw things the way we believed they should be rather than as they really were. For many years, for example, Jack believed that antidepressant medications were superior to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in the treatment of an anxiety condition called panic disorder. That is what his professors insisted was true, and it was part of being an obedient student to believe them. When studies were published that showed that CBT worked, he searched hard for flaws in the experimental methods or interpretation of those studies to convince himself that the new findings were not sufficient to dislodge his belief in medication’s superiority. Finally, he challenged a CBT expert, David Barlow, now of Boston University, to do a study comparing the two forms of treatment and, to his surprise, CBT worked better than medication.19

Fortunately, Jack let the data have its way and changed his mind, but until that point he worked hard to confirm his prior beliefs. This happens all the time in science and is the source of some very passionate scientific debates and conflicts in every field. It also turns out that neuroscientists, using sophisticated brain imaging techniques, have been able to show the ways in which different parts of the brain respond to challenges to fixed ideas with either bias or openmindedness. The challenge for those of us who favor adherence to scientific evidence is to support the latter. In this effort we are too often opposed by anti-science charismatic leaders.

If A Came Before B, Then A Caused B

Uncertainty, as we explain in chapter 4, “Causality and Filling the Ignorance Gap,” is uncomfortable and even frightening to many people. It is a natural tendency to want to know why things are as they are, and this often entails figuring out what caused what. Once again, this tendency is almost certainly an evolutionarily conserved, protective feature—when you smell smoke in your cave, you assume

there is a fire causing it and run; you do not first consider alternative explanations, or you might not survive. We are forced to assign causal significance to things we observe every day. If you hear the crash of a broken glass and see your dog running out of the room, you reach the conclusion immediately that your dog has knocked a glass off a tabletop. Of course, it is possible that something else knocked the glass off and frightened the dog into running, what epidemiologists might call reverse causation, but that would be an incorrect conclusion most of the time. Without the propensity to assign causality, we would once again get bogged down in all kinds of useless considerations and lose our ability to act.

In many ways, however, the causality assumption will fail us when we are considering more complicated systems and issues. This is not a “chicken and egg” problem; that is a philosophical and linguistic conundrum that has no scientific significance. We know that chickens hatch from eggs and also lay eggs so that neither the chicken nor egg itself actually came first but rather evolutionarily more primitive life forms preceded both. By causality we are talking here instead about the way in which the scientific method permits us to conclude that something is the cause of something else. If you look again at our list of examples of anti-science views, you can see that a number of them are the result of disputes over causality. There is no question, for example, that HIV causes AIDS; that fluoride in drinking water prevents tooth decay; and that burning oil, gas, and coal causes global warming, and we are similarly certain that vaccines do not cause autism. Yet there are individuals and groups that dispute these clear scientific facts about causality.

If one has a child with autism, the temptation to find a cause for it is perfectly understandable. The uncertainty of why a child has autism is undoubtedly part of the heartbreak faced by parents. Many initially blame themselves. Perhaps the mom should not have eaten so much fried food during pregnancy. Or maybe it is because the dad has a bad gene or was too old to father a child. Guilt sets in, adding to the anguish of having a child who will struggle throughout their life to fit in. Such parents in distress become highly prone to leap to a causality conclusion if one becomes available, especially if it allows us to be angry at someone else instead of ourselves. Once an idea like vaccines cause autism is circulated and supported by advocacy groups

it becomes very hard for scientists to dislodge it by citing data from all the studies showing that the conclusion is wrong. So the tendency to want or need to find causal links will often lead us to incorrect or even dangerous scientific conclusions.

It’s Complicated

What is it about Ebola that makes it an epidemic in some West African countries like Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone but a very small threat in America? Why, on the other hand, is the flu virus a major threat to the health of Americans, responsible for thousands of deaths in the last 30 years? Why is the novel coronavirus a serious threat to adults everywhere, although perhaps not as threatening for children? The answer lies in the biology of these viruses. The Ebola virus, like HIV, influenza, and coronaviruses, are RNA viruses that are converted to DNA once inside a human cell, which allows them to insert themselves into the host cells’ genome, to replicate and then move on to infect more host cells. The Ebola viruses’ main reservoir is the fruit bat, and bats are also believed by many experts to have been the reservoir for the novel coronavirus that triggered the COVID-19 pandemic. Ebola is spread by contact with bodily fluids of an infected individual20; it is not, like coronaviruses, flu, or chicken pox, an airborne virus. This is a very important point: one can catch the flu from someone merely by sitting nearby and inhaling the air into which they cough or sneeze. A person can infect another person with the flu or COVID-19 from as far as six feet away. Ebola does not spread that way. One has to handle the blood, urine, feces, or vomit of someone with Ebola to get it. Hence, the chance of spreading flu is much greater than the chance of spreading Ebola. The people most at risk for contracting Ebola are healthcare workers and family members who care for infected people. The incubation period for the Ebola virus is between 2 and 21 days, and an individual is not contagious until they become symptomatic. This is also different from the flu or coronavirus, which can be spread before a person becomes symptomatic. Thus, we know when a person with Ebola is contagious; we may not if the person has the flu or COVID-19. Did you get all of that? Those are the facts. Do you now understand the difference between RNA and DNA viruses or the mechanisms by