CONTENTS

List of Figures and Tables vii

Acknowledgments ix

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in the Texts and Notes xiii

1. Introduction 1

2. Neoclassical Realist Theory, Alliance Politics, and Nonproliferation 36

3. The United States and Israel’s Nuclear Weapons Program, 1961–1973 64

4. The United States and Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Program, 1975–1990 112

5. The United States and South Korea’s Nuclear Weapons Program, 1970–1981 160

6. The United States and Taiwan’s Nuclear Weapons Program, 1967–1978 211

7. Conclusions 259

Index 277

FIGURES AND TABLES

Figures

1.1 Neoclassical Realist Theory 15

1.2 Spectrum of (Bilateral) Asymmetric Alliances 19

Tables

1.1 States with Active and Abandoned Nuclear Weapons Programs, 1941–2016 24

2.1 Possible Combination of Values on the IVs and the DV 48

2.2 Possible Combination of Values on the IVs, the IVV, and the DV 55

2.3 Alternative Theories, IVs, and Testable Hypotheses 61

2.4 Cross-Case Comparisons of Alternative Theories 63

7.1 Empirical Support for Alternative Hypotheses 263

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have been interested in great power politics, nuclear weapons, and the United States’ relationships with strategically vulnerable (and often, obstreperous) allies for as long I can remember. By the time I started my graduate studies in Harvard University’s Government Department in the early 1990s, however, the Cold War had ended, the Soviet Union dissolved, and both nuclear weapons and great power competition appeared relegated to the dustbin of history. The international relations subfield of political science, especially its security studies wing, appeared to be in existential crisis. Now, twenty-five years later, great power competition, nuclear weapons and proliferation, and the United States’ relations with vulnerable allies are back in the news, on the minds of policymakers, and at the forefront of scholarly research agendas.

I simply could not have completed this book without the support of many mentors, research institutions, colleagues, friends (not frenemies), and family.

Throughout my career, I have admired international relations scholars whose works transcend different schools of theories (realism, liberalism, and constructivism) and different levels of analysis, who ask big and important questions, and who combine a commitment to theory construction with detailed historical research. I am supremely fortunate to have three such scholars as mentors and friends: Tony Smith, Benjamin Miller, and T. V. Paul.

Tony was my colleague, mentor, and trusted confidante in the Tufts University Political Science Department until his retirement in 2016. He is a brilliant and prolific scholar of comparative politics, international relations, and US foreign policy. He and I rarely see “eye to eye” on theoretical matters—he is a proponent of Wilsonian liberalism and I am a (neoclassical) realist. We do share an interest in the cross-fertilization of international relation and international history. We also share a certain bemusement (and sometimes bewilderment) at recurrent patterns in US foreign policy. Over the years, Tony has been one of my strongest supporters. I owe him a tremendous debt.

Ben Frankel, the founding editor of the journal Security Studies, introduced me to Benny Miller in the early 2000s. I had read Benny’s first book as a PhD student. I was impressed by his willingness to step beyond the confines of Kenneth Waltz’s structural realism and to develop a theory to explain the integrative dynamics between the superpower rivalry and the rivalry between his native Israel and its Arab adversaries during the Cold War. Over the years, Benny has become a dear friend and mentor.

Finally, T. V. Paul has been a source of inspiration and support for many years. It would be an understatement to call him an accomplished, influential, and prolific international relations scholar. He is also an extremely generous scholar and superb mentor of graduate students and younger scholars. Much of my thinking about regions and regional power dynamics originated with a chapter that he asked to me contribute to volume he edited on International Relations Theory and Regional Transformation. I benefited from his scholarship on the India-Pakistan conflict, status hierarchies in world politics, and nuclear proliferation. Finally, T. V. provided extensive written comments on several chapters, offering insightful criticisms and suggestions to improve the book manuscript.

I first began to conceive of this project while on sabbatical in spring semester 2013. T. V. invited me to spend the month of April 2013 as a faculty fellow at the Université de Montreal–McGill University Centre for International Politics and Security Studies. The Associate Professor Research Fellowship awarded by the Office of the Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts University in spring semester 2015 enabled me to do some preliminary research toward this book.

In May and June 2016, I had held a research fellowship at the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway. I am grateful to Asle Toje, the research director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute, for his hospitality and his interest in my scholarship. I had the good fortune to present very early versions of chapters 1 and 3 at the Institute and at the Nobel Symposium on “The Causes of Peace” held at Solstad Hotel and Bad in Øs Commune, Norway.

I revised the earlier chapters and wrote the final two empirical chapters during my fellowship at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, DC, between September 2017 and May 2018. I could not have imagined a more supportive, collegial, and intellectual stimulating environment.

I am especially grateful to Robert V. Litwak, the Wilson Center’s senior vice president and director of the International Security Studies Program, for his support, encouragement, and insightful comments on my work. Kim Conner, Arlyn Charles, Lindsay Collins, and Beverly Thomas in the Office of Scholar and Academic Relations were wonderfully supportive. Janet Spikes, the director of the Wilson Center Library, and Michele Kamalich and Katherine Wahler, research librarians, were extremely helpful in obtaining books from the Library of

Congress and from various university research libraries in the Washington, DC, area. I thank Charles Kraus, a program associate in the Wilson Center’s History and Public Policy Program, for sharing the declassified documents he obtained from the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Jimmy Carter Presidential Library. I am grateful to the AY 2017–2018 class of Wilson Center scholars for their feedback on my work, especially Michael Gordon, Amy Holmes, Stephen Kaplan, Aynne Kokas, Akira Kurosaki, Patrick McEachern, Neeti Nair, Elizabeth Stanley, and Irene Wu.

Many colleagues and friends provided written comments and suggestions on various parts of this manuscript. I would like to thank Stephen Brooks, Timothy Crawford, Jeffrey Friedman, Ronan Tsemin Fu, Brendan Rittenhouse Green, Patrick James, Igor Kovic, Alexander Lanoszka, Jennifer Lind, Mary McKinney, Jonathan Markowitz, Nicholas Miller, Evan Bradon Montgomery, Nuno Monteiro, Daryl Press, Brain Rathbun, Evan Resnick, Randall Schweller, Joshua Shifrinson, Benjamin Valentino, and William Wohlforth. Alex Lanoszka generously gave me access to declassified documents he obtained through the Remote Archives Capture Program (RAC) at the Ford and Carter Presidential Libraries, as well as at the National Archives II in College Park.

I am especially grateful to Norrin Ripsman and Steven Lobell, my collaborators on several previous projects, for their support, wisdom, and friendship over the years. Our scholarly collaboration has deeply shaped how I think about international politics and international relations theory. Our friendship is one of the most rewarding aspects of my academic career.

In addition to the Nobel Institute and the Wilson Center, I presented parts of this manuscript at the Dartmouth College’s Dicky Center for International Understanding; the Department of Political Science at the University of Cincinnati; the Science, Technology, and Society (STS) Program Faculty Seminar at Tufts University; the Center for International Studies at the University of Southern California; and the International Studies Association Annual Convention. I thank the participants and the discussants at those seminars and conference panels.

I have had superb research assistance at Tufts University and at the Wilson Center. At Tufts, my research assistants included David Wallsh and Prashanth Parmeswaran, both PhD students at the Fletcher School, and Zachary Shapiro, Patrick Hamon, Jason Peluso, Austin Brush, and Jameson Moore, who were, at the time, undergraduates majoring in international relations. At the Wilson Center, my “scholar interns” were Salman Ameri, Alexander Roberts, and Jeffrey Hunter Johnson. Their assistance was invaluable.

Three other people at Tufts University deserve mention. Elizabeth Remick and Ioannis (Yannis) Evrigenis have been loyal friends and valued colleagues for many years, as has our department administrator, Paula Driscoll. I thank them each for their encouragement, support, and friendship.

I am particularly grateful to Oxford University Press. I would like to thank my editor, David McBride, for this enthusiasm for this project, as well as his patience in awaiting the delivery of the final manuscript. I thank Emily Mackenzie for shepherding this book through the production process.

Finally, I would like to thank my family, specifically my family of choice. Paul R. Fisher has lived with this book project longer than anyone else, aside from my two “research” cats—Micah and Biff. I thank him from the bottom of my heart.

Jeffrey W. Taliaferro

Boston

November 2018

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS USED IN THE TEXTS AND NOTES

ABM Antiballistic missile

ACADA Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, United States

ADD Agency for Defense Development, South Korea

AEC Atomic Energy Commission, United States

AECA Arms Export Control Act of 1976, United States

AID Agency for International Development, United States

APC Armored Personnel Carrier

AWACS Airborne Warning and Control System

BJP Bharatiya Janata Party, India

CAEC Chinese Atomic Energy Council, Taiwan

CANDU Canada Deuterium Uranium

CBMs Confidence Building Measures

CCP Chinese Communist Party

CENTCOM Central Command, United States

CIA Central Intelligence Agency, United States

CINCPAC Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Command, United States

CINCUSFK Commander-in-Chief, United States Forces in Korea

CINUNC Commander-in-Chief, United Nations Command, Korea

CIST Chungshan Institute of Science and Technology, Taiwan

CPSU Communist Party of the Soviet Union

CTBT Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

CWIHP Cold War International History Project, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

D Democratic Party, United States

DCI Director of Central Intelligence, United States

DEFCON Defense Condition

DIA Defense Intelligence Agency, United States

DMZ Demilitarized Zone, Korea

DNSA Digital National Security Archives

DoD Department of Defense, United States

DoE Department of Energy, United States

DoS Department of State, United States

DPRK Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, commonly known as North Korea

DRA Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

DSAA Defense Security Assistance Agency, United States

EA Bureau of East Asia and Pacific Affairs, Department of State

ERDA Energy Research and Development Administration, United States

ESF Executive Secretariat File

EUCOM European Command, United States

EUR Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, Department of State

EURATOM European Atomic Energy Community

EXCOM Executive Committee, National Security Council, Kennedy administration (1961–1963)

EXDIS Exclusive Distribution

EXIM Export Import Bank, United States

FAA Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, United States

FMET Foreign military education and training

FMS Foreign military sales

FOIA Freedom of Information Act, United States

FRG Federal Republic of Germany, commonly known as West Germany, 1949–1990

FRUS Foreign Relations of the United States

FY Fiscal Year

GBL George Bush Presidential Library

GFL Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

GOI Government of Israel

GOJ Government of Japan

GOP Government of Pakistan

GROC Government of the Republic of China (Taiwan)

HAK Henry A. Kissinger

HEU Highly Enriched Uranium

HFAC House Foreign Affairs Committee

HSTL Harry S. Truman Presidential Library

IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency

IAEC Israeli Atomic Energy Commission

IDAF Israel Defense Air Force

IDF Israel Defense Forces

INER Institute of Nuclear Energy Research, Taiwan

INR Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Department of State

ISA Office of International Security Affairs, Department of Defense

ISI Inter Services Intelligence, Pakistan

JCL Jimmy Carter Presidential Library

JCS Joint Chiefs of Staff, United States

JFKL John F. Kennedy Library

KAERI Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, South Korea

KANUPP Karachi Nuclear Power Plant, Pakistan

KCIA Korea Central Intelligence Agency

KMT Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party), Taiwan

KNFDI Korea Nuclear Fuel Development Institute, South Korea

KPA Korean People’s Army, North Korea

LBJL Lyndon B. Johnson President Library

LEU Low Enriched Uranium

LWR Light Water Reactor

MAC Military Assistance Command

MAP Military Assistance Program

Memcon Memorandum of Conversation

MND Ministry of National Defense, South Korea or Taiwan

MOFA Ministry of Foreign Affairs, various countries

MOST Ministry of Science and Technology, South Korea

MOU Memorandum of Understanding

NAC North Atlantic Council

NARA National Archives and Records Administration

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NEA Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, Department of State

NIC National Intelligence Council

NIE National Intelligence Estimate

NIO National Intelligence Officer

NNPA Nuclear Nonproliferation Act of 1978, United States

NNWS Non-Nuclear Weapons State

NODIS No Distribution Without Permission

NPIHT Nuclear Proliferation International History Project, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

NPL Richard M. Nixon Presidential Library

NPT Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons of 1968, commonly known as the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty

NRX National Research Experimental

NSA National Security Agency, United States

NSA National Security Archive, George Washington University

NSA EBB National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book

NSC National Security Council, United States

NSDM National Security Decision Memorandum

NSPG National Security Planning Group, National Security Council, Reagan administration (1981–1989)

NWS Nuclear Weapons State

OES Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, Department of State

OMB Office of Management and Budget, United States

OPEC Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries

OSD Office of the Secretary of Defense, United States

PACOM Pacific Command, United States

PD Presidential Decision

PDPA People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan

PPP Pakistan People’s Party

PRC People’s Republic of China, commonly known as China

PRC Policy Review Committee, National Security Council, Carter administration (1977–1981)

PRM Presidential Review Memorandum

PSF President’s Secretary’s File

PTBT Partial Test Ban Treaty

R Republican Party, United States

RG Record Group, National Archives

ROC Republic of China on Taiwan, commonly known as Taiwan

ROK Republic of Korea, commonly known as South Korea

ROKG Republic of Korea Government

RRL Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

SACEUR Supreme Allied Commander–Europe

SALT Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty

SAM Surface-to-air missile

SCI Bureau of International Scientific and Technological Affairs, Department of State

SEA Southeast Asia

SecDef Secretary of Defense, United States

SecState Secretary of State, United States

SF Subject File

SFRC Senate Foreign Relations Committee

SLOC Sea Lanes of Communication

SNIE

Special National Intelligence Estimate

S/P Policy Planning Staff, Department of State

SRC Senior Review Committee, National Security Council, Carter administration (1977–1981)

SSA Security Supporting Assistance

TelCon Telephone Conversation

TRA Taiwan Relations Act of 1979, United States

TRR Taiwan Research Reactor

UN United Nations

UNC United Nations Command (Korea)

UNSC United Nations Security Council

UNSCR

USAID

United Nations Security Council Resolution

United States Agency for International Development

USDDO US Declassified Documents Online

USG

United States Government

USSR Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, commonly known as the Soviet Union

WEC Weapons Exploration Committee, South Korea

WHORM White House Office Record Management

WMD Weapons of mass destruction

WSAG Washington Special Actions Group, National Security Council, Nixon and Ford administrations (1969–1977)

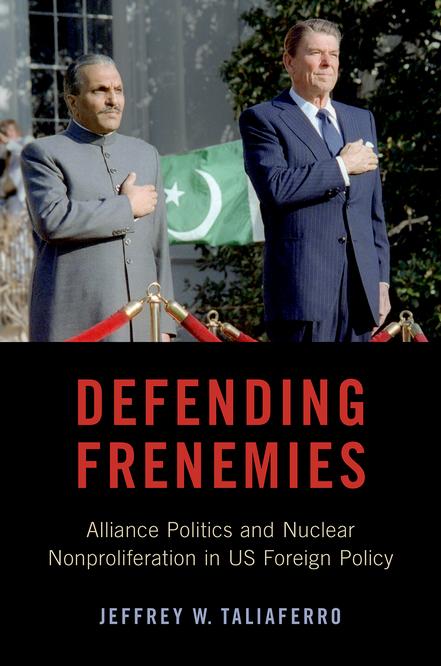

Defending Frenemies

Introduction

When has the United States employed coercive strategies, such as intrusive inspections of nuclear facilities, economic sanctions, or the withdrawal of US military personnel, toward a strategically vulnerable ally in an effort to restrain or even halt that ally’s nuclear ambitions? When is the United States more likely to offer a strategically vulnerable ally tangible inducements, such as conventional arms transfers and explicit security guarantees, to accomplish the same nonproliferation objectives? And when is the United States likely to acquiesce in an ally’s development of nuclear capabilities?

These questions arise in part because US hegemony underpins the global nuclear nonproliferation regime. Much of that regime originated in the 1960s and the 1970s, although unilateral efforts by Washington policymakers to control the spread of fissile materials and nuclear technology date back to the Baruch Plan in 1945. Historian Francis J. Gavin contends that nuclear nonproliferation, the containment of great power adversaries, and the promotion of economic openness have been the three key pillars of US grand strategy for the past seventy years: all three are means to preserve the United States’ power preponderance and its hegemonic role in the international system since World War II.1

I beg to differ. As the succeeding chapters explain, the strategies the United States pursued in support of one pillar—containment—sometimes undercut the strategies it pursued in support of a second pillar—nonproliferation. In some circumstances, US policymakers were so concerned with preventing the Soviet Union from increasing its military, economic, or political involvement in a region, that they pursued accommodative nonproliferation strategies to vulnerable allies, up to and including the provision of generous US military

1 Francis J. Gavin, “Strategies of Inhibition: U.S. Grand Strategy, the Nuclear Revolution, and Nonproliferation,” International Security, Vol. 40, No. 1 (2015), pp. 9–46. For an analysis of how the maintenance of power preponderance became a core objective of US grand strategy after World War II, see Melvyn P. Leffler, A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992).

assistance packages in exchange for allies’ pledges to abide by nuclear “red lines.” Yet, in other circumstances, US policymakers concluded that thwarting the nuclear programs of weaker allies was necessary for the achievement of other geostrategic objectives in a region, whether that objective was containing growth of the Soviet Union’s military, economic, or diplomatic involvement or later enlisting China as an “ally of convenience” against the Soviet Union.

These questions also arise because for seven decades the United States has exercised hegemony through its military alliances. These include multilateral treaty alliances such as North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO); bilateral defense pacts with Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the Philippines; and nontreaty security partnerships with states such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Pakistan, and Israel. Currently, the United States maintains defense ties, in one form or another, with some sixty other countries. These alliances not only enable the US armed forces to maintain command of the global commons and to project kinetic force into distant regions, but also enable Washington to exert a certain amount of leverage over allies’ foreign policies and military strategies.2 Yet the United States also has actively tried to thwart the nuclear weapons ambitions of its own allies, in addition to the nuclear ambitions of the Soviet Union and China. Over the past quarter century, the United States has also tried to thwart the nuclear weapons and long-missile development programs of regional adversaries like Libya, Iraq, Iran, and North Korea.

This book examines how the United States has bargained with four strategically vulnerable and occasionally obstreperous allies in three volatile regions from the early 1960s to the early 1990s. The book presents a historical and comparative analysis of how successive US presidential administrations employed both inducements and coercive diplomacy in their dealings with Israel, Pakistan, the Republic of Korea, and Taiwan over nuclear proliferation.

The nonproliferation strategies the United States has undertaken toward these allies resulted from the interplay of international (systemic) forces and domestic politics. In assessing the consequences of an ally’s nuclear ambitions, presidents and their advisers made initial calculations about the current distribution of power in the region where the ally was located, as well as the time horizons for threats to US interests in that region. Yet the type of strategies the United States ultimately pursued, which ranged from overt coercion to accommodation, were also shaped by American domestic politics. The height of the domestic mobilization hurdles the administration had to overcome, specifically the degree of opposition or support in Congress, played an intervening role. As

2 Michael Beckley, “The Myth of Entangling Alliances: Reassessing the Security Risks of U.S. Defense Pacts,” International Security, Vol. 39, No. 4 (2015), pp. 7–48.

a consequence, the United States sometimes pursued overtly coercive strategies to thwart the nuclear ambitions of some allies, but far more accommodating strategies toward the nuclear weapons programs of other allies. Occasionally, high domestic mobilization hurdles led presidential administrations to pursue what I term hybrid strategies toward nuclear-aspiring allies—that is, strategies that combined elements of coercion and accommodation.

Drawing upon neoclassical realism, I propose that presidents and their administrations will pursue coercive nonproliferation strategies toward an ally, when they perceive the United States as facing a favorable regional power distribution and long time horizons for threats to US interests in that region. However, this presumes the domestic mobilization hurdles to pursuing a coercive strategy are low. Conversely, presidents and their administrations will likely offer inducements toward a nuclear-aspiring ally or even acquiesce in an ally’s maintenance of a latent nuclear capability, when they perceive the United States as facing an unfavorable regional power distribution and short time horizons for threats to US interests in that region. This also presumes, however, that the domestic mobilization hurdles to pursuing such an accommodative strategy are low.

The succeeding chapters test hypotheses derived from this neoclassical realist theory against four historical nonproliferation disputes between the United States and an ally (or quasi-ally). Chapter 3 examines the strategies employed by the administrations of Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson to halt Israel’s secret nuclear weapons program between 1960 and 1969 and then the President Richard M. Nixon administration’s accommodation to a nucleararmed Israel in exchange for certain guarantees between 1969 and 1973. The strategies employed by the administrations of Presidents Gerald R. Ford, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan to thwart Pakistan’s efforts to develop a nuclear weapon between 1975 and 1990 are examined in chapter 4. Chapter 5 and 6 examine the strategies employed by the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations to halt the nuclear weapons and missile programs of South Korea and Taiwan, between 1970 and 1981 and between 1967 and 1978, respectively.

All four cases are of interest for scholars of international politics, nuclear proliferation, and the history of US foreign relations more broadly. For example, the “special understanding” that Nixon negotiated with Israeli prime minister Golda Meir in autumn 1969 and the nuclear “red lines” that Reagan and his surrogates established with the Pakistani military dictator General Muhammad Zia-ulHaq between 1982 and 1985 had implications for the balance of power in the Middle East and South Asia. These nonproliferation arrangements, as well as the accompanying transfers of advanced weapons to Israel and Pakistan, would also shape the United States’ later efforts to diffuse the Arab-Israeli and India-Pakistan conflicts. Likewise, the efforts by the Ford and the Carter administrations to

coerce ROK President Park Chung-hee and ROC premier (later president) Chiang Ching-kuo into ending their respective nuclear weapons programs had implications for the United States’ security commitments in East Asia.

Although this book focuses on historical cases of nuclear proliferation, the neoclassical realist theory developed herein is relevant to other key challenges facing the United States and various allies in the coming years. Thus, far being a purely academic exercise, the book seeks to offer insights for the Washington policy community in managing the fraught relationships with various allies in East Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East on issues of nuclear proliferation, crisis management, the resolution of long-standing territorial disputes, counterterrorism strategies, and defense spending.

US Hegemony and the Problem of Nuclear Proliferation

Broadly speaking, hegemony connotes both a state’s preponderance of material power—in terms of both economic and military capabilities—and its leadership role in the international system. There are multiple and competing definitions of “hegemony” among different schools of international relations theories. Some theories emphasize the politico-military aspects of the hegemon’s role and others focus on the institutional, economic, and normative underpinnings of that role and the resulting benefits for other states.3 Most definitions, however, acknowledge the hegemon’s relative power advantage and its provision of “public goods” in the realms of security and international political economy. In short, hegemons create and enforce international rules.

I adopt Steven E. Lobell’s definition of a global hegemon as a state with sufficient material capabilities to simultaneously exert military and/or economic dominance across several regions of the globe. Global hegemons may be great powers with vast formal empires, such as the Spanish Empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries or the British Empire in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They may also be great powers with far-flung spheres of

3 Charles P. Kindleberger, The World in Depression, 1929–1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973); Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Robert O. Keohane, After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984); Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (New York: Random House, 1987); A. F. K. Organski, World Politics (New York: Knopf, 1958); A. F. K. Organski and Jacek Kugler, The War Ledger (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980); and David A. Lake, Hierarchy in International Relations (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009).

influence or regions of strategic concern such as the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War and continuing to the present day.4 In the aftermath of World War II, the United States created and maintained a network of international institutions, alliances, and forward military bases that provided public goods, namely, economic openness and military security. Military alliances enabled Washington to exercise some measure of influence over regional powers and weaker states.5

Lobell’s regionally differentiated framework highlights two dynamics relevant for the present book. First, global hegemons often face different challengers across geographic space due to the loss-of-strength gradient—the erosion of the ability to project military capabilities over long distances due to logistics, command, control, communications, and intelligence (C3I) difficulties, morale problems, and the degree of local resistance to foreign forces—and due to the differentiated nature of power.6 Second, since hegemons rarely have the requisite human or financial resources to simultaneously dominate all categories of military capabilities (e.g., land, sea, and air forces), they will tend to favor one over the other. “This differential characteristic of power reduces the probability that a single actor can dominate all regions of the globe simultaneously,” which, in turn, limits the number of regions a hegemon could effectively dominate.7 In other words, since hegemons have finite resources, leaders have to make tradeoffs in redressing emerging threats in different regions.

The terms “dominance” and “regions” require a bit of explanation. Dominance is not synonymous with control over international outcomes. Hegemons do not always “get their way” in international politics, despite having a relative power advantage over rival great powers and local actors. Dominance is also not synonymous with territorial control or military occupation of the states within a

4 See Steven E. Lobell, The Challenge of Hegemony: Grand Strategy, Trade, and Domestic Politics (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2003), p. 8.

5 See Keohane, After Hegemony; G. John Ikenberry, After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001); Ikenberry, Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011); Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Stephen D. Krasner, Defending the National Interest: Raw Materials Investments and U.S. Foreign Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978); Robert Gilpin and Jean M. Gilpin, The Political Economy of International Relations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987); Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, World out of Balance: International Relations and the Challenge of American Primacy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008); and Brooks and Wohlforth, America Abroad: The United States’ Global Role in the 21st Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

6 On the loss-of-strength gradient see Kenneth E. Boulding, Conflict and Defense: A General Theory (New York: Harper, 1962), pp. 260–262 and 268–269.

7 Ibid., p. 11.