Formystudents

Foreword

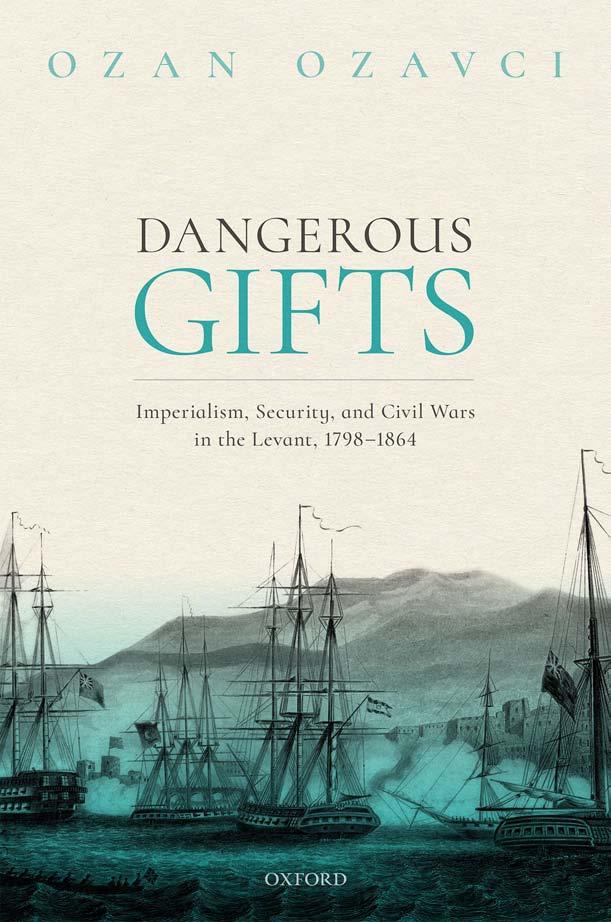

Almostsixyearsago,whenIembarkeduponthisbookproject,thepreliminary conceptIhadinmindwasverydifferentfromtheendresult.Myplanwastowrite acomprehensivemicro-historyoftheinternationalcommissionthatwasdispatchedtoOttomanSyriaaftertheviolentsummerof1860.Alongtheway and, Imustconfess,notsoonafterIbegantheproject asetofquestionsstruckme, upendedthebook’sstructure,andresultedinanenormousreviewofmyintentions:bywhatright,Iwondered,didtheso-calledEuropeanGreatPowersclaim theresponsibilitytosupplysecurityintheLevantinthelongnineteenthcentury evenwhenthesovereignauthoritywasopposedtotheirintervention?Onwhat legalgrounds?Howdiditallbegin?

At first,Ithoughtofexplainingtheseinalongbackgroundchapterbefore Idelvedintothehistoryofthecommission.Butthisdidn’tquitework.Themore Ireadthefascinatingexistingliteratureontheseveralepisodesthatformedthe prehistoryof1860,themorequestionsIwasleftwithabouttheseevents,about theirconnectionswithoneanother,theirmicro-globalnuances,andthehistorical, political,legal,andeconomiccontinuities.Theambitiousendeavourtoaddress themalmostorganicallyledmetoamassiverestructuringofthemanuscripthalfwaythroughtheproject.

Whatwassupposedtobeabookabouttheyears1860–62thusturnedintoa studyofnearlyacenturyofEuropeanGreatPowerinterventionismintheLevant, andthereceptionandimplicationsoftheseacts,aswellaspersistentpatterns,and culturesofsecurity.Mytaskthenbecamewritingahistorythathingestogetherthe existingliterature, fillingthegapsasfarasIwasable abookthathighlightsthe long-standingvectors,overtorcovert,previouslynoticedorunnoticed,but withoutlosingsightoftheideas,ideals,emotions,andobservationsofseveral historical figureswhoselivesandbiographicalexperiencehaveusuallyremained un-orunder-exploredinpreviousstudies.

Yet,indoingso,myaimhashardlybeentowriteanotherSaidian,antiOrientalistorpost-Orientalistbook.Instead,Ihaveendavouredtoupholda thirdnarrativethatgoesbeyondbothOrientalismandits(corrective)rejection, beyondthelikesofbothBernardLewisandFouadAjamiandEdwardSaid.This narrativeembracesthecomplexityofthehistoricalrealitythroughin-depthand multi-archivalresearchtoofferamoresubstantiativeandlessimpressionistic analysisofinterventionismandviolenceintheLevant.

Theverysameconsiderationledmetoproposeanewparadigm,andtouse securityasadrivingforceofpoliticalandsocialchange,ratherthanproducing

anotherhistoryofwesternization,modernization,orsecularizationofthe (Ottoman)MiddleEasternsocietiesaftertheir ‘encounterwiththeWest’.Since thespatialscopeofthebookislimitedtotheeasternMediterraneancoasts,and sinceIdevoteonlyverylimitedspacetotheeventsthatsimultaneouslytranspired inareasincludingMesopotamiaandtheArabianPeninsula,Ihavedecidedtouse theterm ‘theLevant’ asthegeographicalfocusofthebook,eventhoughtheregion thatbecameatheatreofinterventionscoveredinthebookhascometobeknown as ‘theMiddleEast’ asoftheearlytwentiethcentury.

DangerousGifts cameintobeingaspartofalargerprojectfundedbythe EuropeanResearchCouncil(ERC), ‘SecuringEurope,FightingItsEnemies’ . Thankstothis,Ihavebeenabletocooperatewithseveralbrilliantscholars.One ofthem,theprimeinvestigatoroftheproject,BeatricedeGraaf,readthedraft chaptersofthebookandmademostusefulcomments.Withherpatienceand encouragement,withtheoccasionallunchanddinnermeetingssheorganized,she hasbeenasourceofimmensemoralsupport.ConstantinArdeleanu,Erikde Lange,AnnelotteJensen,WouterKlem,MelleLyklema,TrinekePalm,Joep Schenk,andJossieTil-Duijstersasassiduouslyreadmydraftchaptersandoffered insightfulcomments.SusanneKeesmanhasbeenofgreathelpinguidingme throughthebureaucraticminutiaeoftheprojectaswellashelpingmetosettlein theNetherlands.MyrthevanGroningenandAndreaDörrkindlyhelpedmeto sortoutcopyrightandotherpracticalissuesinthe finalstagesoftheproject.Erik Goosmandesignedtheappealingmapsusedinthisbook.

TheERCfundinghasalsoallowedmetoenlistthesupportofanumberof researchassistantswhoselinguisticand/orlogisticalreachbroughttomyconsiderationprimaryandsecondarysourcesinseverallanguagesandfromnumerous archives,whichIwouldnototherwisehavebeenabletomakeuseof.Markus Wegewitz,DominikLoibner,andTheresaHerzogsuppliedmewithmaterials fromarchivesandlibrariesinBerlinandVienna,workingwiththechallenging Kurrentschrift,takingnotes,andtranslatingtheirnotesfromGermaninto English.ElenaLinkovafoundanddispatchedsourcesfromthearchivesand librariesinMoscowandStPetersburg.Zienabal-BakryandTarekSabraprovided assistancewithlocating,takingnotes,andtranslatingArabicprimary(mostly archival)andsecondarymaterialsfromEgypt,Syria,andLebanon.Filiz Yazıcıoğluhasbeentremendouslygenerousinofferinghersupport.Notonly didshehastentotheOttomanarchivesandIslamicResearchInstituteinIstanbul andsendmecopiesofanarchivalmaterialorabookwheneverIneededher urgenthelp.Shealsohelpedme ‘decipher ’ someofthemoreintricateOttoman texts.IamindebtedtoPavlosKardoulakisfortakingcopiesofarchivalmaterials inBritainandFranceformyuse.

Thetaskoffreeingthemanuscriptfrommylinguisticmistakeswasskilfully takenupbyAlastairPaynter.

SelimDeringil,JonathanConlin,andJonathanParryhavereadthedraft manuscriptandprovidedmewithexcellentfeedback.Iwasluckyto findSelçuk Dursun(abi)withinreachwheneverIneededhissupportwiththetransliteration ofsubtleOttomansources.

MyeditorsatOxfordUniversityPress,especiallyStephanieIreland,believedin theprojectfromthebeginning.TogetherwithKatieBishopandCathrynSteele, shedisplayedanimpressivedegreeofprofessionalisminarrangingfortimelypeer reviewsandputtingtogetherthecontract.Stephanie,Katie,andCathrynhave patientlyrespondedtomyendlessquestionsandinquiriesduringthevarious stagesofthispublicationjourney.Mycopy-editorSarahBarretwasadmirably diligent,whileSaravananAnandanhasbeenamodelprofessionalduringthe productionofthebook.

Devotingnearlysixyearsofmylifetoresearchingandwritingahistoricalbook hasbeenademandingendeavour,tosaytheleast,whichsometimesentaileda hermit-like-lifestyle,spendingweeksinarchives,andsacri ficesofsorts,especially onthepartofthoseIlove.Mydearestfamilyandfriendshavetirelesslysupported meallalongevenwhenIdisappearedfromtheirlivesforextendedperiodsoftime. Theyhaveshownanindefatigablefaithinmeandtheproject,whichhasbeenmy mainsourceofmotivationandenergy.EstherMeininghaushasalsohelpedme withthetransliterationofArabicsources,whilepatientlylisteningtomeforhours ramblingaboutthecontentsofthebook.JuliaKozakhasassistedmewiththe transliterationofRussiansources,anduncomplaininglyreadalldraftchapters, tellingherhonestopinionevenwhenIwouldn’tlikeit.Iamgratefultoallofthem fortheirendlesspatience,support,and,aboveall,fortheirpresence.

GratefulIamalsotoallthetrulyhelpfularchivistsandlibrariansImetduring research,andmynumerouscolleaguesandstudents,whosenamesIunfortunately cannotlistinthelittlespaceIhavehere.Ican,however,saythatIhavebeen privilegedtohavetheopportunitytodiscusstheveryquestionsIaskedmyself whilewritingthebook notonlywithexpertscholarsbutalsowithmystudents, hundredsofthem,fromallwalksoflifeandliterallyfromallovertheworld, duringtheteachingofseveralcoursemodules.Nearerthecompletionofthe project,Isharedwithmystudentsthedraftchaptersofthemanuscript,and fine-tuneditscontentsandtonefollowingtheirsuggestions.Theyevenconducted researchintothevarioussubjectscoveredinthebookaspartoftheirassignments, whichintroducedmetonewliteratureandprimarysourcesthatIhadnotbeen awareof.

‘Ilikereadingstories,’ oneofmystudentsatUtrechtoncetoldme,notsoulless scientificanalyses.Amongtheseveralchallengesinwritingabookonentangled histories,themostdifficultonehasbeentodevelopoutofa fiendishlycomplex storyanarrativethatisbothintelligibleandcaptivatingforreaders.Theyshould bethejudgeoftheextenttowhichIsucceedinthis.

Inshort, DangerousGifts hasbeentheresultofatirelessteameffort.Thefact thatmynameappearsasitssingleauthoroughtnottooutshinethedegreeof collaborativelabourwhichallowedittomaterialize.Withoutmyresearchteam, withoutthesupportofmycolleagues,withoutmyfamilyandfriends,andwithout mystudents,thisbookcouldnothaveseenthelightoftheday.Idedicateitto theseunseenco-creators.

November2020

Utrecht

OzanOzavci

PARTI. AVANTLEMOT

PARTII.THEINVENTIONOF

PARTIII.THEMOUNTAIN

Introduction

Justiceisabalancesetupamongmankind.

IbnKhaldun, Muqaddimah¹

TwomonthsafterhisarrivalinOttomanSyriainSeptember1860,thePrussian bureaucratJohannLudwigGuidovonRehfues(1818–97)andhiscolleaguesset offonahauntinglymemorablejourneytoDamascus.²LeavingBeirutearlyinthe morning,theyrode firstupMountLebanon.Fromalltheheightstowhichtheir pathtookthem,theycouldseethesmoke-stainedrubbleofonce flourishing villagesinthecountryside.³Thepicturesquehillsdidnothidethegrimfactthat acivilwarhadstrucktherehalfayearearlier.ItwasthelastdayofNovemberand themenonhorsebackwererepresentativesoftheEuropeanPowersatthe commissiontheyhadbeentaskedwithsettingup:PierreJeanAdolphede Weckbecker(1808–71)wastheAustrianplenipotentiary,LeonPhilippeBéclard (1819–64)theFrench,andEvgeniiPetrovicNovikow(1826–1903)represented Russia.Sincehewasunwell,theBritishcommissioner,FrederickHamiltonTemple-Blackwood,1stMarquessofDufferinandAva(1826–1902),hadstayed inBeirut.

The fivecommissionershadbeendispatchedtoSyriaforwhatwasarguablya ‘humanitarian ’ missiontoinvestigatetheoriginsofviolence,monitortheretributionandindemnificationprocesses,andreorganizethecountry’sadministration. Theywerethe firstmentoestablishaninternationalsecurityinstitutioninthe Levant. ⁴ AftercrossingtheplainsoftheBekaavalleyandovercomingthechallengesoftheAnti-LebanonMountains,thecompanionsmadetheirentranceinto DamascusbehindanOttomanimperialcavalryuniton1December.Thestreets

¹IbnKhaldun, Muqaddimah: AnIntroductiontoHistory,vol.2,trans.FranzRosenthal(Princeton, NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress,2015),145.

²In1860,theterm ‘Syria’ ,or Bilâdal-Sham,referredtotheareathatencompassespresent-daySyria, Lebanon,Jordan,andPalestine:BruceMasters, ‘Syria’,in EncyclopaediaoftheOttomanEmpire,ed. BruceMastersandGáborÁgoston(NewYork:FactsonFile,2009),550. ³JohannLudwigGuidovonRehfuestoAlexanderGustavAdolphFreiherrvonSchleinitz,2Dec. 1860,GStA,III.HAMdA,INr.7568,f.385.

⁴ Bytheterm ‘Levant’ IreferherenotonlytotheArab mashriq buttotheregionalongtheeastern MediterraneancoastsofthelateOttomanEmpirethatstretchedfromAlexandriainEgypttoIzmir/ Smyrna,theStraitsthatconnecttotheBlackSea,theeasternGreekcoasts,andtheirhinterland.The term ‘Levantine’ willbeusedtodenotetheinhabitantsofthesespaces.Forarecentstudyonthe conceptof ‘Levant’,seeRanaIssaandEinarWigen, ‘LevantineChronotopes:PrismsforEntangled Histories’ , ContemporaryLevant 5(1)(2020):1–12.

DangerousGifts:Imperialism,Security,andCivilWarsintheLevant,1798–1864.OzanOzavci,OxfordUniversityPress. ©OzanOzavci2021.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198852964.003.0001

were filledwithacompactcrowdattractedbythecurioussight.⁵ Whenthey arrivedattheirresidence,RehfuesimmediatelywenttotheChristianquarterto seeforhimselfthetown’scondition.Duringthecourseofhalfaday,heconducted athoroughinvestigation,andvisitedthelocationsatwhichthekillingshadtaken placeinJuly,whichresembled,inhiswords, ‘persecutionsintheearliesttimeof theChristiancalendar’.Hefrequentlyhaltedinhisjourney,andonlyastrong desiretoobservethetragicscenesforhimselfgavehimthestrengthtocarryon. Although fivemonthshadpassedsincetheevents,andthebodiesofthose murderedhadbeentakenawayorattheveryleastcoveredwithrubble,the manifoldremainingtracesstillpaintedadisturbingpictureofwhathadhappened there.Inthehourshespentatthesite,itwasasifRehfueshadwitnessedthe horrorforhimself.Thenextday,hewroteinadispatchtoBerlinthathewould neverforgetwhathehadseeninDamascus.⁶

InthelandstheEuropeancommissionersrodepastduringthosetwodays, morethan10,000peoplehadperishedandtensofthousandshadbeendisplaced betweenlateMayandearlyJuly1860.TheworstviolentoutburstinlateOttoman Syria,theDruze–Maronitecivilwar,latersparkedthekillingofaround3,000 DamasceneChristianson9–10July.⁷ ThenewsalarmedEuropeancapitals, attractedimmensepublicattention,andprovokedfuryandconsternationon thepartoftheOttomangovernment.EventhoughSultanAbdülmecid IappointedFuadPașa(1814–69),oneofhiseminentministers,asspecialenvoy tosuppressthe ‘disturbances’ andestablishorderandtranquillityinthecountry, thediplomaticmanoeuvresoftheSublimePorte⁸ wouldnotbeenoughtoprevent thedispatchofaFrenchexpeditionaryarmyto ‘aidtheSultan’ inprotectingthe Christianpopulations.⁹ Norwouldtheysufficetoavoidtheestablishmentofan internationalcommissionwhich,Ottomanministersbelieved,infringedthesovereigntyoftheirempire.

The1860interventionwasonlyoneofmanyEuropeaninterventionsinthe Levantintheeighteenthandnineteenthcenturies.StartingwithNapoleon Bonaparte’soccupationofEgyptin1798,theself-defined fiveGreatPowers(in alphabeticalorder,Austria,Britain,France,Prussia,andRussia)hadpreviously assumedresponsibility,eitherindividuallyorcollectively,forsupplyingsecurityin theregion.Theyhadstagedhithertounprecedentedmilitaryoccupations ‘forthe benefitofthelocals’.Theyhaddrawnlines,partitionedlands,andimposedrules,

⁵ LeonBéclardtoAntoineThouvenel,12Dec.1860,AMAE50MD/139.

⁶ RehfuestoSchleinitz,2Dec.1860,GStAIII.HAMdA,INr.7568,385.

⁷ OntheDamasceneevents,seeEugeneL.Rogan, ‘SectarianismandSocialConflictinDamascus: The1860EventsReconsidered’ , Arabica 51(4)(Oct.2004):493–511.

⁸‘TheSublimePorte’ or Bâb-ı Âli (‘thePorte’)isatermusedbyEuropeanandOttomanagentsasof thelate18thc.torefertotheOttomanimperialministries.

⁹ R.Edwards, LaSyrie,1840–1860.Histoire,politique,administration,population,religionset mœurs,événementsde1860d’aprèsdesactesofficielsetdesdocumentsauthentiques (Paris:Amyot, 1862),164.

laws,administrativesystems,andtreatiesonthelocals,usuallyagainsttheirwill. Theyhadalsoventuredonthe firstso-called ‘humanitarian’ interventionsin history,beforeestablishingas-yet-unknowninternationalsecurityinstitutions, suchasthecommissiononSyriathatRehfuesandhiscompanionsweretasked withsettingup.¹⁰

Mybookisabouttheseeighteenth-andnineteenth-centuryforeigninterventionsintheLevant theirmaking,theatres,reception,andrepercussions.Ittraces thegenealogyoftheseuniquepracticesofrecenthistory,askinghowitallbegan how,fromthelateeighteenthcentury,thethreatperceptionsandinterestsofthe WesternPowersandLevantineinhabitantsbecameinterwoven,andhowandwhy historicalactors,bothimperialandperipheral,¹¹EuropeanandLevantine,unwarilygrappledwithaviciousandintricateparadoxthere:anever-increasingdemand forsecuritydespiteitsincreasingsupply.¹²

AftereachmajorEuropeanGreatPowerintervention,i.e.theuseofforceor pressurebyoneormoredominantstates ‘tointerferewithandexertpowerover theaffairsofaweakersovereignentity’,easternMediterraneancoastswerefurther destabilizedandbecamevulnerabletocivilwars.¹³First,thestrifeinOttoman Egypt(1802–11)thatfollowedtheFrenchoccupationof1798–1801andoverlappedwiththeBritishinterventionof1801–3;then,followingthe1827Navarino interference,thecivilwarbetweenthepașaofEgypt,MehmedAli,andthe SublimePortethatengulfedtheentireOttomanworld(1832–41);and, finally, thehostilitiesbetweentheDruzeandMaronites(1841–60)inOttomanSyria betweentheQuadrupleAlliance’sinterventionin1840andthe1860armed intervention.Alltheseoutbreaksofviolencehaddiverseandcompoundorigins rootedinnumerous, predominantlydomestic,factors.Yet,atthesametime,they wereallfuelledbyinternationaldynamics,connections,andinteractions,and werethenquelledalmostalwaysthroughthe filterofglobalimperialinterests.

Thereisalreadyarichanddiverseliteratureonthehistoricalepisodesconsidered inthisbook.TheFrenchinvasionofEgyptin1798,theso-called ‘humanitarian’

¹⁰ FordiscussionsofwhatmakestheseinterventionsintheOttomanEmpire ‘humanitarian’ ,seeesp. GaryJ.Bass, Freedom’sBattle:TheOriginsofHumanitarianIntervention (NewYork:RandomHouse, 2008);AlexisHeraclidesandAdaDialla, HumanitarianInterventionintheLongNineteenthCentury: SettingthePrecedent (Manchester:ManchesterUniversityPress,2015);andDavideRodogno, Against Massacre:HumanitarianInterventionsintheOttomanEmpire (1815–1914)(Princeton,NJ:Princeton UniversityPress,2011).

¹¹Iusetheterm ‘periphery’ asastructuralmetaphortodemarcatethehierarchical,asymmetrical, andexploitativenatureofboththeOttomanandglobalimperialsystems,wherebythemainbenefactorsoftheasymmetriesweretheimperialcentres(metropoles).

¹²Onthenotionof ‘securityparadox’,seeChristopherDaase, ‘OnParadoxandPathologies: ACulturalApproachtoSecurity’,in TransformationsofSecurityStudies:Dialogues,Diversityand Discipline,ed.GabiSchlag,JulianJunk,andChristopherDaase(Abingdon:Routledge,2016),86.

¹³Onthedefinitionof ‘foreignintervention’,seeElizabethSchmidt, ForeignInterventioninAfrica: FromtheColdWartotheWaronTerror (NewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress,2013),3.

interventionsintheOttomanEmpire,theconflictbetweenMehmedAliPașaand theSublimePorte,andthecrisesinOttomanLebanonhaveallbeenanalysedin numerousfascinatingstudies.¹⁴ HereIwillhingetogether,andcriticallyaugment andcomplement,thisdiverseliterature,ratherthanexaminingeachepisodein isolationandomittingtheirimmediatelinksorthelong-standingvectorsthat connectedtheseepisodes.¹⁵ NorwillmyfocusbeonWesternperceptionsand conceptionsofsecurityonly.

AsDavideRodogno,oneoftheleadingauthoritiesonthehistoryofhumanitarianism,candidlyadmits,nobookintherichliteratureon ‘humanitarian’ interventionsinthenineteenth-centuryOttomanEmpirehashistoricizedthe experienceofthe ‘targetstate’.¹⁶ Thelives,ideas,emotionsandthreatperceptions, andinterestsofLevantinesthemselveshaverarelybeenmentionedorspecifically foregroundedinhistoricalanalysesofsecurity,withtheexceptionofafewstudies thatfocusonviolenceintheregionepisodically.¹⁷ HereIwilllookto fillthese gaps.Withoutattributingtotheso-calledperipheralLevantineactorsthesolerole of ‘bargainingchips’ , ‘juniorpartnersinthepowergame’ ,or ‘trouble-makers’ , Iwillpayparticularattentiontothepartthatthelocalactorsplayedinenabling interventionismandintheproductionofviolenceintheLevant.¹⁸

¹⁴ Seeesp.JuanCole, Napoleon’sEgypt:InvadingtheMiddleEast (NewYork:PalgraveMacmillan, 2007);KhaledFahmy, AllthePasha’sMen:MehmedAli,HisArmyandtheMakingofModernEgypt (New York:CambridgeUniversityPress,1997);GilbertSinoue, LeDernierPharaon.MéhémetAli(1770–1849) (Paris:PygmalionGerardWatelet,1997);CarolineGaultier-Kurhan, MéhémetAlietlaFrance1805–1849. HistoiresingulièreduNapoléondel’Orient (Paris:Maisonneuve&Larose,2005);MarsotA.L.Al-Sayyid, EgyptintheReignofMuhammadAli (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1984);VernonJ.Puryear, InternationalEconomicsandDiplomacyintheNearEast:AStudyofBritishCommercialPolicyinthe Levant,1834–1853 (Stanford,CA:Archon,1969);LetitiaW.Ufford, ThePasha:HowMehemetAliDefied theWest,1839–1841 (Jefferson,NC:McFarland,2007);KamalS.Salibi, TheModernHistoryofLebanon (London:Weidenfeld&Nicolson,1965);LeilaT.Fawaz, AnOccasionforWar (London:I.B.Tauris, 1994);CaesarE.Farah, ThePoliticsofInterventionisminOttomanLebanon, 1830–61 (London: I.B.Tauris,2000);UssamaMakdisi, TheCultureofSectarianism:Community,HistoryandViolencein NineteenthCenturyOttomanLebanon (Berkeley:UniversityofCaliforniaPress,2000);YannBouyrat, Devoird’intervenir.L’interventionhumanitairedelaFranceauLiban,1860 (Paris:Vendémiaire,2013).

¹⁵ Thefewexceptionsare:EfraimKarshandInariKarsh, EmpiresoftheSand:TheStrugglefor MasteryintheMiddleEast,1789–1923 (Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversityPress,1999); M.S.Anderson, TheEasternQuestion,1774–1923:AStudyinInternationalRelations (NewYork:St. Martin’sPress,1966);AlexanderL.Macfie, TheEasternQuestion1774–1923 (Harlow:Longman,2013).

¹⁶ Rodogno, AgainstMassacre,2–3.Fortworecentstudiesthatform,toanextent,theexception here,seeWillSmiley, ‘WarWithoutWar:TheBattleofNavarino,theOttomanEmpireandthePacific Blockade’ , JournaloftheHistoryofInternationalLaw 18(1)(2016):42–69,andHakanErdem, ‘“Do NotThinkoftheGreeksasAgriculturalLabourers”:OttomanResponsestotheGreekWarof Independence’,in CitizenshipandtheNation-StateinGreeceandTurkey,ed.ThaliaDragonasand FarukBirtek(Abingdon:Routledge,2005),67–84.

¹

⁷ Makdisi, Culture;Farah, Politics. Moreover,owingtotheabundanceofGreatPowerinterventions incivilwarsintheglobalsouthsincetheSecondWorldWar,arichsocial-scientificliteraturehaslong examinedhowforeignmeddlinghasextendedthedurationofcivilwarsandincreasetheintensityof violence.Someofthesestudiesbuildtheirargumentson19th-c.caseswithoutspecifyingwhichcases thesewere.Seee.g.DylanBalcj-Lindsay,AndrewJ.Enterline,andKyleA.Joyce, ‘Third-Party InterventionandtheCivilWarProcess’ , JournalofPeaceResearch 45(3)(2008):345–63.

¹⁸ PınarBilgin, ‘The “Western-Centrism” ofSecurityStudies: “BlindSpot” orConstitutive Practice?’ , SecurityDialogue 41(2010):617;BahgatKorany, ‘StrategicStudiesandtheThirdWorld:

MyargumentisthatGreatPowerinterventionsinthenineteenth-century Levantneedtobeconsiderednotonlyinreferencetotheirimmediatecauses, theatres,andimplications.Itisessentialtotakeintoaccountthecontinuitythat European and Levantineactorssawinregionalaffairsfromthelateeighteenth centurythroughuntilatleastthemid-nineteenth.Thereisaneedtoforeground thepersistentpatternsor ‘culturesofsecurity’ withinwhichviolencewasgeneratedandsustained,andhowimperialism thepractices,ideologies,andsystems ofbuildingorsustainingempire¹⁹—andsecurity definedinthisbookbroadlyas ‘theanticipatedstateofbeingunharmedinthefuture’²⁰—actedasorganizing principlesofinternationalrelations.HereIwillplacetheEuropeanandLevantine questsforsecurityinawiderhistoricalcontextasthedrivingforcesofan entangledhistory,whichoffersusnewwaystoconstruetheviciouscyclesof GreatPowerinterventionsandcivilwarsthatenvelopedtheLevant.Thisanalysis helpsusdiscernthecomplexityofthesituationthehistoricalactorswere embroiledin,andidentifywhospokeauthoritativelyaboutsecurityatthetime, whatthethreatandinterestperceptionsofthediversehistoricalactorswere, whichdiscursivepracticestheyadopted,whowerethenetbeneficiariesand,where applicable,whopaidforsecurity thatis,whose financialresponsibilityitwas ultimately.

HistoricizingtheEasternQuestion

Intheeighteenthandlongnineteenthcenturies,oneofthepersistentparadigms thatcausallylinkedtheGreatPowerinterventionsintheLevantwas ‘theEastern Question’.Anear-perfecthistoricalembodimentoftheotherwiseabstractand ambivalentimperialism–securitynexus,theEasternQuestionoriginatedwith endeavoursintheeighteenthcenturytodealwiththeallegeddecadenceofthe OttomanEmpire.²¹Likeallsecurityissues,itturned ‘itseyeexclusivelytothe

ACriticalEvaluation’ , InternationalSocialScienceJournal 38(4)(1986):547–62;TarakBarkawiand MarkLaffey, ‘ThePostcolonialMomentinSecurityStudies’ , ReviewofInternationalStudies 32(2006): 343–4.

¹⁹ Idefinetheterm ‘empire’,relyingontheadmirableworkofBurbankandCooper,as ‘large politicalunits,expansionistorwithamemoryofpowerextendedoverspace,politiesthatmaintain distinctionandhierarchyasthey[striveto]incorporatenewpeople’.JaneBurbankandFrederick Cooper, EmpiresinWorldHistory (Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress,2010),8.Foraslightly adjusteddefinition,seeJenniferPitts, ‘PoliticalTheoryofEmpireandImperialism’ , AnnualReviewof PoliticalScience 13(2010):213.

²

⁰ BeatricedeGraafandCornelZwierlein, ‘HistoricizingSecurity:EnteringtheConspiracy Dispositive’ , HistoricalSocialResearch 38(1)(2013):52.

²¹Recently,historianshaveinvitedustoinvokesocial-scientifictheories,suchassecuritization theory,i.e.theidentificationofissuesassecuritythreatsinordertoconvinceanaudience(thedecisionmakers)totakeextraordinarymeasuresagainsttheseperceivedthreats,whilehistoricizingsecurity.De GraafandCornelZwierlein, ‘HistoricizingSecurity’,49.However,thenarrowfocusofsecuritization theoryonlegitimacy andforthatmatteronthenationstatesandthepolitiesbetterequippedtovoice

future ’.²²Accordingtothemainstreamnarrative,themajorEuropeanempires perceivedashared,existentialthreatinthedreadfulprospectofthedominanceof oneoranotheroftheGreatPowersoverthestrategic,prizemorselsofthe OttomanEmpire(suchastheStraitsortheSuezarea,thetransportationroutes toIndiaandCentralAsia).Theybelievedthatsuchageostrategicadvantage obtainedbyoneEuropeanempiremightadverselyaffectthebalanceofpower amongthemandthreatentheexistenceoftheothers.

Historicallyspeaking,theEasternQuestionemergedinaperiodthatcoincided withtheindependenceoftheAmericasandtheshiftofglobalcolonialcompetitiontoAsia.Itwasthen,inthenineteenthcentury,thattheLevantbecamea strategicallycrucialgatewayforthenewandnowvitallyimportantcoloniesthat suppliedEuropewithresourcesandmarkets,whichsustainedtheireconomies andpermittedpoliticalstabilityinthemetropoles.Inconnectiontothis,global capitalismincreasinglyexpandedintotheLevant nowastrategicallyandeconomicallycentralregion whereitmetwiththelocalownersforprofit.

Theinterlockingofgeostrategicandeconomicundercurrentsgeneratednew questions.Theseincludedtheneedforoverseasempirestopreserveinternational commerce,ensuringtheuneven flowofcapital,goods,andresources,andsecuringthenewlyacquiredterritoryandproperty,aswellasintegratingthesometimes reluctant,orevenresistant,localpopulationsintotheneweconomicand financial structures,fromapositionofpowerandhierarchy.Atthesametime,growing Christianmissionaryactivityengenderedproblemswithrespecttotheprotection ofdenominationalagentsandestablishments.Theywereincreasinglyviewedby Levantines,regardlessofthereligiousinclinationsofthelatter,asboththreatsto localculturesandinstrumentsformoralempowerment.

Infact,thecapitulations thelegalagreementswiththeOttomanEmpirethat grantedcommercialandlegalprivilegestoEuropeansubjects hadallowedthe EuropeanPowerstointerfereinlegalsecurityissuesintheOttomanworldsince thesixteenthcentury.²³Butthesewereusuallylimitedtoindividualexperiences. AndeventhoughFranceandRussiahadassumedtheresponsibilityofprotecting theirthreatperceptionsandtopersuadetheiraudience bringsintoseriousquestionitsapplicabilityin imperialhistoricalcontexts.BenediktStuchteyandAndreaWiegeshoff, ‘(In-)Securitiesacross EuropeanEmpiresandBeyond’ , JournalofModernEuropeanHistory 16(3)(2018):325–6.

²²DeGraafandZwierlein, ‘Historicising’,52.

²³ForinsightfuloverviewsofcapitulationsandextraterritorialityintheOttomanEmpire,see EdhemEldem, ‘CapitulationsandWesternTrade:WesternTradeintheOttomanEmpire. Questions,IssuesandSources’,in TheCambridgeHistoryofTurkey,ed.SuraiyaN.Faroqhi (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2006),281–335;UmutÖzsu, ‘OttomanEmpire’,in The OxfordHandbookoftheHistoryofInternationalLaw,ed.BardoFassbenderandAnnePeters(Oxford: OxfordUniversityPress,2012),446;andhis ‘TheOttomanEmpire,theOriginsofExtraterritoriality, andInternationalLegalTheory’,in TheOxfordHandbookoftheTheoryofInternationalLaw,ed. FlorianHoffmannandAnneOrford(Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2016),123–37;alsoseeTuran Kayaoğlu, LegalImperialism:SovereigntyandExtraterritorialityinJapan,theOttomanEmpireand China (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2010).

theCatholicandOrthodoxsubjectsoftheOttomansultanssincetheseventeenth andeighteenthcenturies,theselongremainedmerelyrhetoricalgestures.They appearedtoservemoretobolsteraffectivetiesthantoactuallyproduceconcrete actions.

Whatchangedinthelateeighteenthandparticularlythenineteenthcentury wasthat,asBuzanandLawsonhaveshown,withtheglobaltransformationthat resultedfromtheunevenandcombineddevelopmentofsocietiesworldwide, unprecedenteddifferentialsinthemodesofpolitical,economic,military,and technologicalpowergraduallyemergedbetweenasmallgroupofso-called ‘leading-edge’ Europeanempiresandtherest.²⁴ Thesedisparitiesweretimeand againprovedbyeasyvictorieswonbythesuperordinatesinwarsandthrough territorialannexationsandunevencommercialtreaties.Theyengenderedthe creationofnewhierarchiesinworldpoliticswherebyinternationalizedcontroversieswerealmostexclusivelyaddressedwiththeinterferenceofthedominant Powers.²⁵

Itwasintheageofglobaltransformationandtheemergenceofhierarchiesthat generationsofEuropeanandLevantineactors(statesmen,bureaucrats,diplomats, militaryandnavalofficers,secretagents,journalists,merchants,missionaries, bankers,feudaloroligarchicallords,etc.)establishednewtransimperialnetworks amidthesharedthreatposedbytheEasternQuestion.Theseagentslookedto furthertheircommoninterestsinmaintainingtheOttomanEmpireorprocuring benefitsfromherallegedweakness,ifnottotaldestruction.Totheseends,they mobilizedtheirresources(armies,navies,weapons,technologies,norms,funds, etc.)across,between,andbeyondimperialborders.²⁶ Theydevelopeddiverse, sometimesunprecedentedrepertoiresofpower:militaryoccupationsconducted forthe ‘benefitofthelocals’,theso-called ‘humanitarian’ interventions,slow evacuationofoccupyingarmies,surrogateorproxywars,pacificnavalblockades, theestablishmentofinternationalandextraterritorialsecurityinstitutions,transimperiallymediatedlocaladministrativestructures,partitionsbyinternational agreementsortreaties,orthedispatchofmilitary,naval,andcivilianadvisers,etc. Thesediscursivepractices²⁷ were(self-)justi fiedbymeansofthedeploymentof

²⁴ BarryBuzanandGeorgeLawson, TheGlobalTransformation:History,ModernityandtheMaking ofInternationalRelations (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2015).

²⁵ Hierarchyisconsideredhereasa ‘systemthroughwhichactorsareorganizedintovertical relationsofsuper-andsubordination’:AyşeZarakol, ‘TheorisingHierarchies:AnIntroduction’,in HierarchiesinWorldPolitics ed.AyşeZarakol(Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2017),1.

²⁶ DanielHedingerandNadinHee, ‘TransimperialHistory:Connectivity,Cooperationand Competition’ , JournalofModernEuropeanHistory 16(4)(2018):432.

²⁷ Theconceptof ‘discourse’ isusedheretorefertolinguisticandnon-linguisticpractices, ‘asystem ofrepresentationthathasdevelopedsociallyinordertomakeandcirculateacoherentsetofmeanings’ andmaterializedinconcretepracticesandrituals:JuttaWeldes,MarkLaffey,HughGasterson,and RaymondDuvall, ‘Introduction:ConstructingInsecurity’,in CulturesofInsecurity:States,Communities andtheProductionofDanger,ed.JuttaWeldes,MarkLaffey,HughGasterson,andRaymondDuvall (Minneapolis:UniversityofMinnesotaPress,1999),16.

newsetsofreligiouslyimbuedandEnlightenmentnormsandprinciplesfrom whichapositivistanduniversalizedinternationallawwasspawned.²⁸ Indue course,theyturnedintorecurringbehaviouralpatternsorthemodusoperandi ofsecurityintheLevant.²⁹ Atransimperialsecurityculturewasthuswoven spontaneouslyaroundtheEasternQuestion. *

TheFrenchinvasionofEgyptwasanopeningmomentofthiscultureofsecurity. Inthebeginning,particularlyduringtheglobalCoalitionWars(1792–1815),the unfoldingrepertoiresofpowerwerecharacterizedbyrivalryamongthemajor EuropeanandOttomanempires.Forexample,theinter-imperial(1798–1801) andproxy(1802–11)warsinOttomanEgyptwerethedirectfruitsoftheAngloFrench/OttomanstrugglefordominationalongtheeasternMediterraneancoasts. Inthe1810s,however,inter-imperialcompetitionintheLevantwentthrough anearlymetamorphosis.WhentheCoalitionWarscametoade finitiveend, duringthepeacetalksatParis,Vienna,andlateratAix-la-Chapellebetween 1814and1818,the(thenself-defined)EuropeanGreatPowersfosteredanunderstandingofsecurityasapublicgoodthatcouldbeobtainedmosteffectively throughcooperation.³⁰ Basedonanadaptationoftheideaofa ‘balanceof power ’ tomeetthethepostwarrealitiesofEurope,theyforgedanexclusive system,theConcertofEurope,tosupervise firstEuropeanandthenglobalaffairs, bymeansofmediationamongthemselvesandinordertoinhibitanyreturntothe horrorsofaEuropeantotalwar.³¹Theyendorsedcollectiveactionandconference diplomacy,andupheldnewprinciplesandcodesofconductsuchasnoninterventionineachother’saffairsorthenecessityofapprovalbytheGreat Powersforterritorialchanges.³²EachtimetheEasternQuestionpressedonthe

²

⁸ Ontheimperialistoriginsofinternationallaw,seeAntonyAnghie, Imperialism,Sovereigntyand theMakingofInternationalLaw (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2005);GerrySimpson, GreatPowersandOutlawStates:UnequalSovereignsintheInternationalLegalOrder (Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,2004).

²

⁹ ForanastuteyetWest-centricdescriptionofthenotionofsecuritycultureasatoolforstudying interventions,seeMaryKaldorandSabineSelchow, ‘FromMilitaryto “SecurityInterventions”:An AlternativeApproachtoContemporaryInterventions’ , Stability:InternationalJournalofSecurityand Development 4(1)(May2015):1–12.

³

⁰ PatrickCottrell, TheEvolutionandLegitimacyofInternationalSecurityInstitutions (NewYork: CambridgeUniversityPress,2016),68–9.SeealsoMatthiasSchulz, NormenundPraxis.Das europäischeKonzertderGrossmächtealsSicherheitsrat,1815–1860 (Munich:Oldenbourg,2009).

³¹LouiseRichardson, ‘TheConcertofEuropeandSecurityManagementintheNineteenth Century’,in ImperfectUnions:SecurityInstitutionsoverTimeandSpace,ed.HelgaHaftendom, RobertKeohane,andCelesteWallender(Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,1999),51;Jennifer Mitzen, PowerinConcert:TheNineteenthCenturyOriginsofGlobalGovernance (Chicago: UniversityofChicagoPress,2013),30;MaartjeAbbenhuis, AnAgeofNeutrals:GreatPowerPolitics, 1815–1914 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2014),40–41.

³²MichaelJarret, TheCongressofViennaanditsLegacy:WarandGreatPowerDiplomacyafter Napoleon (London:I.B.Tauris,2013),362;EricD.Weitz, ‘FromtheViennatotheParisSystem: InternationalPoliticsandEntangledHistoriesofHumanRights,ForcedDeportations,andCivilizing Mission’ , AmericanHistoricalReview 113(5)(Dec.2008):1313–43;PaulW.Schroeder, ‘DidtheVienna

internationalagenda suchastheGreekcrisis(1821–32),theEgyptianquestion (1832–41),theSyrianquestion(1841–64),andtheRusso-Ottomanwars(1828–9 and1853–6) ministerialandambassadorialconferenceswereconvened(or,at least,proposed)withtheultimatepurposeofpreventingthePowersfromsteppingoneachother ’stoesor fightingwithoneanotherintheLevant,aselsewhere intheworld.

Thenceforth,themajorEuropeanPowerscametoconsidercooperationasthe ultimateinstrumentforcontainingthepotentiallydestructiveimplicationsoftheir enduringcompetition.Putanotherway,convergenceamongthePowers(the evolutiontowardsstrategiccooperation)provednottobethebinaryoppositeof divergence(theirdifferinginterestsandrivalries),butitslogicalcompletion:the onlymeanstoensureEuropeansecuritywhilemaximizingglobalimperialinterestswastoacttogether,makingconcessionsforagreatergood.

WhiletheemergenceoftheEasternQuestioninthelateeighteenthcenturyand theFrenchinvasionofEgyptsymbolizedanewbeginningandintensifiedinterimperialrivalriesintheLevantuntiltheearlytwentiethcentury,theViennaorder heldtheserivalriesincheckbyurgingconcertedactionamongthePowers.Itthus changedthenatureofEuropeandialoguetoaconsiderableextent.Inmostcases, thenewinternationalorderreinedinbellicoseunilateralaction.But,aswewillsee inthisbooktimeandagain,italsofacilitatedinterventionsbytheGreatPowersby meansofplacingthemonaquasi-legalplatform,theConcertofEurope.

ThisbecameapatterninnearlyeveryepisodeoftheEasternQuestion.Along theway,likemostsecurityissues,theEasternQuestionitselftookondifferent meaningsatdifferenthistoricalmoments.³³Itwasneverastaticparadigm.³⁴ Inthe lateeighteenthcentury,evenbeforethetermwascoined,itpertainedmostlyto (inhibiting)theRussianplansforthepartitionoftheOttomanEmpireand,after the1789revolution,FrenchexpansionismintheLevant.Inthe1810s,itwasa matterofplacingthesultan’ sempireundertheguaranteeofEuropeanpublic lawinordertoaddressRusso-Ottomandifferences.³⁵ Inthe1820s,itreferredto thediplomaticquandaryoverthe ‘Greekcrisis’.Adecadelater,itwasabout

SettlementRestonaBalanceofPower?’ , AmericanHistoricalReview 97(3)(June1992):683–706;Brian E.Vick, TheCongressofVienna:PowerandPoliticsafterNapoleon (Cambridge,MA:Harvard UniversityPress,2014);BeatricedeGraaf,BrianVickandIdoDeHaan, SecuringEuropeAfter Napoleon:1815andtheNewEuropeanSecurityCulture (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 2019), ‘Introduction’;esp.BeatricedeGraaf, FightingTerrorafterNapoleon:HowEuropeBecame Secureafter1815 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2020).

³³LuciaZedner, ‘TheConceptofSecurity:AnAgendaforComparativeAnalysis’ , LegalStudies 1 (153)(2003):154.

³⁴ Thishasbeenshowninrecentscholarship;Macfie, TheEasternQuestion;LucienJ.Fraryand MaraKozelsky, ‘Introduction’,in Russian–OttomanBorderlands:TheEasternQuestionReconsidered, ed.LucienJ.FraryandMaraKozelsky(Madison:UniversityofWisconsinPress,2014).

³⁵ Inthe1810s,theso-called ‘Polishquestion’ wasalsodiscussedundertheheadingoftheEastern Question.HüseyinYılmaz, ‘TheEasternQuestionandtheOttomanEmpire:TheGenesisoftheNear andMiddleEastintheNineteenthCentury’,in IsThereaMiddleEast?TheEvolutionofaGeopolitical Concept,ed.MichaelE.Bonine(Stanford,CA:StanfordUniversityPress,2011),12.