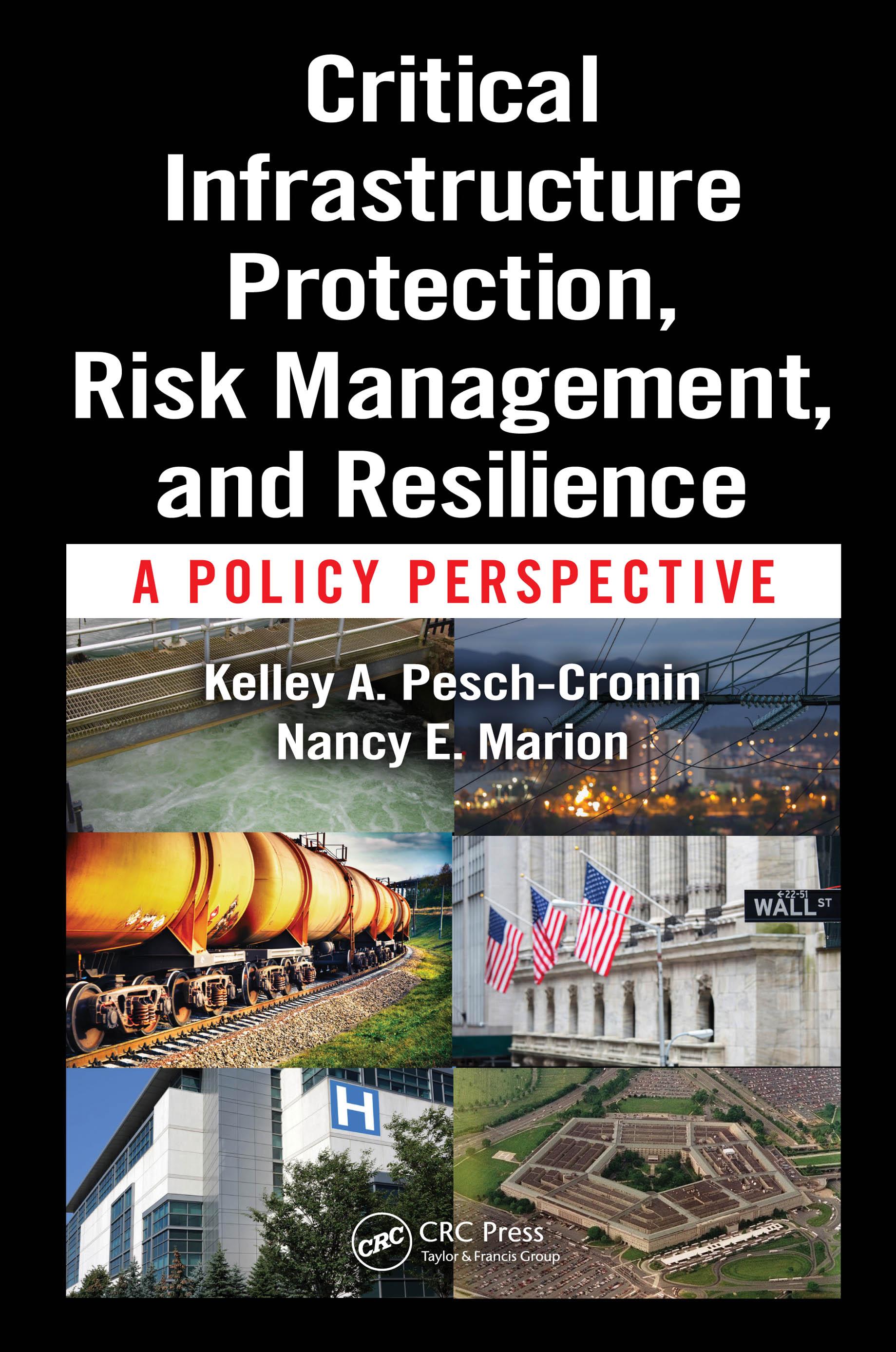

1 Critical Infrastructure and Risk Assessment

INTRODUCTION

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, Louisiana. As a Category 3 hurricane, there were sustained winds of 125 miles/hour and massive ooding. Hundreds of residents were displaced from their homes and had no food, water, shelter, or medical assistance. Much of the city was devastated. Businesses were in shambles.

Many residents of the city believed that the federal government did not respond quickly to meet the needs of the communities and businesses from the damaged areas. Many victims sought relief from the government but found none. The federal agency responsible for providing assistance after a national disaster, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), was accused of failing to provide help for days after the event. Even then, it seemed that FEMA of cials were unprepared to deliver aid and that many government of cials, including President George W. Bush, were not aware of the seriousness of the hurricane and the ensuing damages. The lack of attention resulted in an escalation of destruction and multiple deaths.1

A few years later, in 2008, another hurricane, Ike, slammed into the Gulf states of Texas, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi, again causing widespread damage with multiple injuries and deaths. Afterward, state leaders again accused FEMA of failing to provide needed assistance to residents of those states in a timely manner.2

The same complaints were heard from residents of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut after Hurricane Sandy hit the East Coast of the US in 2012, killing more than 100 people. The heavy rains, powerful wind, and storm surges caused massive ooding in major cities. Water surged through the nation′s Financial Center and New York′s public transportation system. Major power outages affected almost 8 million businesses and homes in 15 states.3 Major airports, schools, and government of ces were closed. Gas shortages only served to complicate the circumstance. Residents were in need of basic necessities of shelter, food, and water and more than 352,000 people registered for assistance from the federal government.4 While many praised the government ′s response to Sandy, 5 others made it clear that FEMA′s response was delayed and they failed to ef ciently provide basic services to those affected by the storm, again escalating the storm′s effects.6

Catastrophes like these and other devastating events can cause a disruption of vital government services that people rely on each day. Disasters can be caused by either a natural event (a hurricane, earthquake, or ood) or a human act (i.e., a terrorist attack). Either way, residents affected by a calamity often do not have the critical services they need to survive in the days after an event. Government agencies and businesses may be unable to provide basic services needed for a community to maintain itself. Citizens may nd themselves without access to water, food, shelter, or power sources. If serious enough, the disruption can pose a serious risk to society: there is a risk that even more citizens will be harmed or killed or additional property will be damaged as looting occurs in the time before services are restored.

Natural events such as Katrina, Ike, and Sandy, and man-made events such as the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 or the subsequent anthrax attacks on media outlets and members of Congress demonstrate how vulnerable assets and systems can be. If they are damaged or incapacitated, even for a short time, there can be a debilitating effect on the nation′s security, economic system, or public health (see Note 3). People may be prevented from traveling from one place to another easily, and needed goods and products may not be accessible. There may not be effective and reliable communication systems, nancial services, power, food, or medical services. Of cials across the country may nd it dif cult to monitor, deter, and if necessary, respond to possible hostile acts. If these disruptions become prolonged, it could have a major impact on the country′s health and welfare.

The damages caused by recent events in the US, both natural and man-made, have made it clear that there is a need to reexamine how the

country protects its assets and seeks to ensure that critical services are available to citizens in the days and weeks following an event. Both victims and nonvictims have called on government of cials to enact policies that will protect the nation′s critical infrastructure so they are better able to withstand events, or if damaged, can recover quickly. These disasters made public of cials realize that the government needed to put more emphasis on the security of the nation′s infrastructure during a disaster or terrorist act, to ensure that basic services are available to citizens. It has become unmistakable that protecting the nation′s critical infrastructure is essential to public health and safety of residents, the economic strength, the way of life, and national security.7 Thus, one of the goals for government of cials in the recent years was to ensure the protection of the country′s critical infrastructure. This way, the country will be safer, more secure, and even more resilient in the aftermath of an event.

Today, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) spends billions of dollars annually to prevent (or mitigate), prepare for, respond to, and recover from an incident, whether it be natural or man-made. The government′s goal has become national preparedness, which they de ne as: “The actions taken to plan, organize, equip, train, and exercise to build and sustain the capabilities necessary to prevent, protect against, mitigate the effects of, respond to, and recover from those threats that pose the greatest risk to the security of the Nation.”8 In order to ful ll the National Preparedness Goal, the focus of DHS shifted from focusing primarily on terrorism threats to all-hazards threats. This shift has been signi cant and continues to be debated as to how best to balance the approach to prevention, response, and recovery.

It is critical that government of cials and private individuals alike understand government attempts to identify and protect the country′s critical infrastructure as they seek to ensure that essential services and goods are available to residents in the aftermath of a disruptive event such as a hurricane, earthquake or ood, or a terrorist attack. The proper identi cation of structures deemed to be critical infrastructure and the strategies to protect them has become a priority in today′s world. Although essential, these steps have also become controversial. It is important to begin our analysis of critical infrastructure protection by de ning essential terms that are used frequently by those who seek to protect the nation′s critical infrastructure. Over time, the meanings of some terms have changed and become muddled. In some cases, the meanings of some terms vary regionally across the country. For that reason, it is important to de ne the terminology that will be used throughout the remainder of the book.

WHAT IS CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE?

The term “critical infrastructure” has changed over time and because of that, the term is sometimes ambiguous or blurred. Prior to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the US, the term “infrastructure” referred primarily to public works (facilities that were publicly owned and operated) such as roadways, bridges, water and sewer, airports, seaports, and public buildings. The main concern at that time was how functional these services were for the public. This began to change during the early 1990s after the nation witnessed major disasters such as the bombings of the World Trade Center (1993) and the Oklahoma City building (1995). About this time, the threat of terrorism was also emerging in the US and consequently, the de nition of what is meant by critical infrastructure has become much broader.

Now the term critical infrastructure is a general term that refers to the framework of man-made networks and systems that provide needed goods and services to the public. In other words, it is the facilities and structures, both physical and organizational, that provide essential services to the residents of a community, which ensure its continued operation. This term includes things such as buildings, roads and transportation systems, telecommunications systems, water systems, energy systems, emergency services, banking and nance institutions, and power supplies. In addition to physical structures and assets, the term incorporates virtual (cyber) systems and people.

In general, critical infrastructure is all of the systems, which are indispensable for the smooth functioning of government at all levels. It is the asset that is vitally important or even essential to a community or to the nation that, if disrupted, harmed, or destroyed, or in some way unable to function, could have a debilitating impact on the security, economics, or national health, safety, or welfare of citizens and businesses.9 There could also be a signi cant loss of life if these services are not provided.

Critical infrastructure can be divided into Tier 1 and Tier 2 facilities. Tier 1 facilities and systems are those structures that, if attacked or destroyed by a terrorist attack or natural disaster, would cause signi cant impacts on either the national or regional level. These would be impacts similar to those that occurred in Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina or resulting from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Tier 2 facilities and systems are less critical but still needed for a strong community (see Note 7, p. A-6). The distinction between a Tier 1 and a Tier 2 asset is used by of cials as they make better decisions about how to allocate resources

for critical infrastructure protection. The categories are reviewed annually and are changed as needed. The Tier 1/Tier 2 list is classi ed and not available to the public (see Note 7, pp. 1–14).

A similar term is key resources. As de ned in the Homeland Security Act of 2002 and the 2003 National Strategy, key resources are the assets that are either publicly or privately controlled and are essential to the minimal operations of the economy and government. These documents identi ed ve key resources: (a) national monuments and icons, (b) nuclear power plants, (c) dams, (d) government facilities, and (e) commercial key assets. By 2009, the number of sectors and key resources expanded to 18 and were called critical infrastructure and key resources. Since then, the concept of critical infrastructure and key resources (CIKR) has evolved to encompass the sectors and resources. For the most part, key resources are not separated from critical infrastructure in today′s nomenclature, and the terms are used interchangeably.

Local Critical Infrastructure

Each community has assets that provide a service to its residents and need to be protected from both natural and man-made events. What assets are de ned or labeled as critical infrastructure can be different in different cities or regions of the country—critical infrastructure assets are different in Cleveland as compared with Los Angeles, or even Tampa or Denver, because they have different weather conditions, different needs, and different assets. In considering a community′s critical infrastructure, it is essential to know how valuable an asset is to that community and whether, or to what extent, it needs to be protected. Community leaders must rank assets by placing some kind of a value on them. In some cases, a community′s critical infrastructure can be one major structure that is very costly to build, maintain, and operate, like a water puri cation plant. Clearly, a community relies heavily on this service, but because of the enormous cost, a community can only afford one of them. Protecting this structure would be vital to the community. This asset provides a needed service to residents, and there would be serious impacts on the health of the community should this plant be harmed in some way. Of cials need to know if an asset is vulnerable to a natural disaster, or if it would be an attractive target for an attack. It is also important to know if there is a back-up or secondary method for providing the service to residents.

Federal Critical Infrastructure

On the federal level, there are thousands of assets that are considered to be critical infrastructure. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 and the Homeland Security Presidential Directive-7 (HSPD-7, 2003) require of cials in DHS to identify the nation′s critical assets and networks (the national infrastructure). This list is found in a document called the National Asset Database, maintained by the Of ce of Infrastructure Protection (OIP). There are 77,000 national assets on the list that are located across the country, with about 5% of those assets (only 1,700) labeled as critical.10 This would include assets such as power plants, dams, or hazardous materials sites.11 The critical infrastructure assets in the US include a power grid that is essential for daily life that is interconnected with other national systems. There are 4 million miles of paved roadways with 600,000 bridges. There is also a complex rail system in the US that includes 500 freight railroads and 300,000 miles of rail track. There are 500 commercial service airports along with 14,000 general aviation airports. In addition, there are 2 million miles of oil and gas transmission pipelines; 2,800 electric plants; 80,000 dams, 1,000 harbor channels, and 25,000 miles of inland, intracoastal, and coastal waterways servicing more than 300 ports and 3,700 terminals. Clearly, if any of these facilities were to be attacked and damaged, communities and residents may be seriously impacted.12

The list of critical assets is sometimes controversial, as of cials in the federal, state, and local governments, and the private sector owners, often disagree about what should be included in the directory. For example, the list includes many assets that are considered to be local assets, such as festivals and zoos, which some of cials argue should not be included. However, DHS includes all assets in an attempt to create a comprehensive inventory of critical infrastructure around the country. Thus, identifying a comprehensive list of national critical assets continues to be an ongoing debate for the DHS.13 The number of assets in each sector is found in Table 1.1.

Private Critical Infrastructure

In addition to having local assets and federal assets, there are also privately owned critical infrastructure assets. Most people have the perception that critical infrastructure is owned and operated by the government, but in reality 80% of the critical infrastructure in the US is owned and operated by the private sector.

Table 1.1 Numbers of Critical Assets by Sector

Source: Moteff, J. 2007. Critical Infrastructure: The Critical Asset Database. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, RL 33648. Retrieved from: http://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/RL33648.pdf. Of ce of the Inspector General. Department of Homeland Security. Progress in Developing the National Asset Database.

Because many assets are owned by private entities, the private sector must be involved in planning for protecting those valuable assets. Many documents, including the National Strategy, the Homeland Security Act, and HSPD-7, address the importance of including all partners in coordinating protection efforts. These documents make it clear that protecting the infrastructure cannot be accomplished effectively simply by the government and the public sectors. Instead, they must work jointly with private sector owners and operators. The government can assist owners and operators of critical infrastructure in many ways, such as providing timely and accurate information on possible threats; including owners in the development of initiatives and policies for protecting assets; helping corporate leaders develop and implement security measures; and/or

helping to provide incentives for companies whose of cials opt to adopt sound security practices (see Note 7, pp. 1–15).

CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE INFORMATION

In addition to critical infrastructure assets, there is also something called critical infrastructure information (CII). This is the data or information that pertains to an asset or critical infrastructure, and is considered to be sensitive but not always classi ed (secret). An example of CII is knowledge about the daily operations of an asset, or a description of the asset′s vulnerabilities and protection plans. CII can also include information generated by the asset such as patient health records or a person′s banking and nancial records. CII could also be any evidence of future development plans related to the asset, or information that describes pertinent geological or meteorological information about the location of an asset that may point out potential vulnerabilities of that facility (e.g., a dam at an earthquake-prone site). In general, CII refers to any information that could be used by a perpetrator to destroy or otherwise harm the asset or its ability to function.

The importance of protecting CII was rst identi ed in the CII Act of 2002, passed by Congress. It was noted that when a private organization chose to share information with government of cials, that information then became a public record and could be accessed by the public through public disclosure laws. Many companies did not want to make that information public, so they were reluctant to work with government agencies and of cials. As a way to protect that information and encourage more cooperation, the Congress created a new category of information they called CII. According to the law, any federal of cial who knowingly discloses any CII to an unauthorized person may face criminal charges. They could be removed from their position, may face a term of imprisonment of up to 1 year as well as nes. The information may be disclosed to other state or local of cials, if it is used only for protection of critical infrastructures. The law was passed to ensure that only trained and authorized individuals who need to know the information can access it and use it only for homeland security purposes.

CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION

To protect the critical infrastructure and CII, and in order to maintain services if an event occurs, it is essential that of cials from the federal, state, and local governments, as well as private owners of the nation′s critical

infrastructure, develop plans not only to protect their assets from possible harm, but also action plans to respond to an attack or other harm. These plans must be reviewed regularly and updated as potential threats continue to change. The term “critical infrastructure protection” (CIP) refers to those actions that are geared toward protecting critical infrastructures against physical attacks or hazards. These actions may also be directed toward deterring attacks (or mitigating the effects of attacks) that are either man-made or natural. While CIP includes some preventative measures, it usually refers to actions that are more reactive in scope. Today, CIP focuses on an all-hazards approach.

The primary responsibility for protecting critical infrastructure, and for responding if it is harmed, lies with the owners and operators, but the federal government and owners/operators work together to identify critical infrastructure, and then to assess the level of risk associated with that asset. The assets’ potential vulnerabilities are determined, and possible methods for reducing the risk are identi ed. If owners and operators are unwilling or unable to participate in this process, the federal government can intervene and assess the protection level and devise a response.14 While most critical infrastructure protection is carried out at federal, state, and local level, there is also a global perspective to protecting critical infrastructure as the world becomes more global.

A related term is critical infrastructure assurance (CIA). This revolves around the process by which arrangements are made in the event of an attack or if an asset is disrupted, to shift services either within one network, or among multiple networks, so that demand is met. In other words, it has to do with detecting any disruptions, and then shifting responsibilities so that services can continue to be met. This can often be done without the consumer′s knowledge.

RISK

The probability that an asset will be the object of an attack or another adverse outcome is its risk.15 Risk is the likelihood that an adverse event will occur,16 and is related to consequences (C), vulnerabilities (V), and threats (T), as described in the following formula. The National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP) expresses this relationship as follows:

Risk = (function of) (CVT)

It is essential that CIKR owners and operators assess the potential risk to their assets using these three elements. This way, they can make policies to protect the critical infrastructure and plans to respond if that were to occur. Each element is described in the following.

Consequence

A consequence is the effect or result of an event, incident, or occurrence. This may include the number of deaths, injuries, and other human health impacts; property loss or damage; and/or interruptions to necessary services. The economic impacts of an event are also critical consequences, as many events have both short- and long-term economic consequences to communities or even to the nation.17 It is important that there is business continuity, which is the ability of an organization to continue to function before, during, and after a disaster (see Note 7, p. A-2).

Vulnerability

A vulnerability is “a physical feature or operational attribute that renders an entity open to exploitation or susceptible to a given hazard” (see Note 17, p. 33). It is easy to think of it as a weakness or aw in an asset that may cause it to be a target for an attack. An aggressor may seek out a vulnerability and use that to strike the asset. In most cases, the major vulnerability is access control whereby unauthorized people can enter the asset (such as a building or open area) to gather information to plan an attack, or even to carry out an attack. To reduce this possibility, it has become common practice to prohibit unauthorized people from entering these types of areas (see Note 17, p. 33).

Structural vulnerabilities need to be addressed and maintained over an extended time rather than relying on a temporary solution or a “quick x.” This extended approach is referred to as long-term vulnerability reduction. The National Preparedness Goal de nes the long-term vulnerability reduction core capability as to “build and sustain resilient systems, communities, and CIKR lifelines so as to reduce their vulnerability to natural, technological, and human-caused incidents by lessening the likelihood, severity, and duration of the adverse consequences related to these incidents” (see Note 8, p. 11). According to the DHS, the initial national capability target is to “achieve a measurable decrease in the longterm vulnerability of the Nation against current baselines amid a growing population based and expanding infrastructure base” (see Note 8, p. 11).

Threat

A threat is a “natural or man-made occurrence, individual, entity, or action that has or indicates the potential to harm life, information, operations, the environment, and/or property.” This term has also been more simply de ned as “an intent to hurt us.”18 Threat has to do with potential harm that can originate from any source, including humans (terrorists or active shooter); natural hazards (different threats for different parts of the country); or technology (a cyberattack). Those charged with protecting critical assets seek to identify possible threats to resources as a way to mitigate harm that could result. It is much easier to identify natural threats such as storms and earthquakes. To a great extent, these threats can be predicted and the possible impact is easier to judge. Plans can be established so that a community is prepared to respond. On the other hand, man-made threats are far less predictable and can occur at any time with unknown consequences, making mitigation and response planning much more dif cult.

RISK ASSESSMENT

Risk assessments of critical assets are carried out as a way to identify potential risks that may exist surrounding an asset, which can then lead into developing courses of action to prevent or respond to an attack. Through data collection and analysis, a risk analysis is an attempt to identify not only threats, but also consequences of an attack. In general, a risk assessment asks, “What can go wrong? What is the likelihood that it will go wrong? What are the possible consequences if it does go wrong?”19 This way, the probability of an incident occurring and the severity (consequence) of that incident will be better understood (see Note 7, pp. 3–7). The analysis can also be used to determine priorities, or what assets are more critical and how should money be spent to protect them. It can also help of cials create plans to protect residents and keep their property safe. Since the September 11, 2001 attack and Hurricane Katrina, public interest in risk analysis has grown dramatically. Risk analysis has become an effective and comprehensive procedure to reduce the possibility of an attack and subsequent damages, and they have become complex.20 Government of cials at the federal, state, and local levels, heads of agencies, and even legislators now incorporate risk analysis into their decisionmaking processes and address risk more explicitly at all levels.21

CRITICAL I NFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION

Risk assessments are completed on an asset, a network, or a system. They typically consider three components of risk as noted earlier, and rely on a variety of methods, principles, or rules to analyze the potential for harm. Some risk assessments are heavily quantitative and rely heavily on statistics and probabilities, whereas others are less quantitative.22 In general, a risk assessment report typically includes ve elements. They are as follows:

1. Identi cation of assets and a ranking of their importance

The rst step in a risk analysis is to determine which infrastructure assets can be considered to be “critical.” Since all assets vary as to how important they are, assets can be, and need to be, ranked. Of cials must determine what properties are needed in a community to ensure services are required. Examples include buildings, water treatment plants, or power plants. They may also decide that certain people are critical, such as medical professionals, police of cials, or government of cials. Another possibility is to include information such as nancial data or business strategies. Risk assessments are then done on those assets that are identi ed as the most critical. The time and resources that would be needed to replace the lost asset must also be part of the analysis. If that asset were lost, how quickly could it be replaced? Are there other assets that could substitute for that one? If the asset was lost, how would services be provided? What cascading effects might occur if one asset were lost or damaged? (see Note 22).

2. Identify, characterize, and assess threats

All potential threats to an asset need to be identi ed. Details about potential threats that should be considered include the type of threat (e.g., insider, terrorist, or natural threat); the attacker′s motivation; potential trigger events; the capability of a person to carry out an attack; possible methods of attack (e.g., suicide bombers, truck bombs, cyberattacks). Analysts can gather information on these topics from the intelligence community, law enforcement of cials, specialists and experts in the eld, news reports in the media, previous analysis reports, previously received threats, or “red teams” who have been trained to “think” like a terrorist (see Note 22).

3. Assess the vulnerability of critical assets to speci c threats

An asset′s vulnerability can be analyzed in many ways. The rst is physical. Here, an analyst would determine things like an

CRITICAL I NFRASTRUCTURE AND R ISK ASSESSMENT

outsider′s accessibility to an asset. The second is technical, which refers to an asset′s likelihood of being the victim of a cyberattack or other type of electronic attack. The third type of vulnerability is operational, or the policies and operating procedures used by the organization. The fourth is organizational, or the effects that may occur if a company′s headquarters is attacked (see Note 22).

4. Determine the risk

Risk is the chance that a disruptive event may occur, as described earlier. Assets are usually rated on their risk, and resources can be allocated to reduce an asset ′s risk.

5. Identify and characterize ways to reduce those risks

An important part of a risk assessment is to determine ways to mitigate or eliminate the risk of an attack. This could be something as simple as banning unauthorized people from entering particular areas or reducing traf c around an asset. Of course, other ways to eliminate the risk of an attack may be more complicated such as building physical barriers or relocating assets.

RISK MANAGEMENT

In risk management, of cials ask, “What can be done? What options are available and what are the associated tradeoffs in terms of cost, risks, and bene ts? What are the impacts of current management decisions on future options?”23 These are efforts to decide which protective measures to take based on an agreed upon risk-reduction strategy.

CONVERGENCE

Many of the critical infrastructure assets are connected to each other in some way. This integration of infrastructure is called “convergence.” This means that if one asset is harmed and unable to serve people, the other assets linked to it may also be unable to perform (see Note 17, p. 31). This is referred to as “cascading” or “escalating” effects. The interconnected nature of critical infrastructure could lead to even more harm to a community than if the assets were independent. In some cases, the interdependencies can be global since many of our assets are linked to those around the world.