COVID-19 Infection

Mild and Moderate COVID-19

More than 80% of documented COVID-19 infections have been considered mild to moderate.1 This doesn’t include asymptomatic cases, which account for 40%–50% of all cases.2

Knowing that one is an asymptomatic carrier has its own set of concerns, as Dr. Rucha Mehta Shah learned: “Little did I know that—while certainly not as traumatic as falling ill—living asymptomatically with coronavirus in the United States would come with its own horrors. When I got the call that I had tested positive, I froze. I had so many questions but could not vocalize any of them. While I am lucky not to have experienced symptoms, asymptomatic disease is still disease. The symptoms are just hidden: feelings of guilt, isolation, fear of infecting those you love, fear of potentially getting sicker.”3

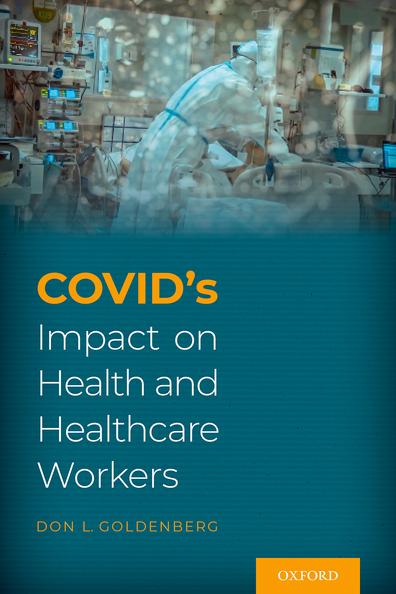

The most common presenting symptoms in patients with COVID infection are fever, cough, fatigue, and dyspnea (Figure 1.1).4 Typical COVID symptoms have been much more alarming than seasonal flu. Different patients reported, “I woke up with a headache that was Top 5 of my life, like someone inside my head was trying to push my eyes out. I got a 100.6-degree fever . . . Everything hurt. Nothing in my body felt like it was working. I felt so beat up, like I had been in a boxing ring with Mike Tyson. I had a fever and chills—one minute my teeth are chattering and the next minute I am sweating like I am in a sauna. And the heavy, hoarse cough, my God. The

1 CDC COVID Data Tracker. Coronavirus Disease 2019. April 20, 2020.

2 Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann Intern Med. September 1, 2020. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-3012

3 Shah RM. The horror of living with coronavirus asymptomatically. The Washington Post July 21, 2020.

4 Sheleme T, Bekele F, Ayela T. Clinical presentation of patients infected with coronavirus disease 19: A systematic review. Infect Dis (Auckl). September 10, 2020. doi: 10.1177/ 1178633720952076.

Figure 1.1. The Most Common Presenting Symptoms in COVID-19 Infection. From: Sheleme T, Bekele F, Ayela T. Clinical presentation of patients infected with coronavirus disease 19: A systematic review. Infect Dis (Auckl). September 10, 2020.

cough rattled through my whole body. You know how a car sounds when the engine is puttering? That is what it sounded like . . . On Day 10, I woke up at 2:30 a.m. holding a pillow on my chest. I felt like there was an anvil sitting on my chest. Not a pain, not any kind of jabbing—just very heavy . . . It was just a loss of all energy and drive. There was no horizontal surface in my house that I didn’t want to just lay down on all day long.”5

Reduction of smell, anosmia, has been one of the most predictive early symptoms since it is uncommon in other viral respiratory infections but present in 20%–70% of COVID-19 cases.6 Smell and taste dysfunction have been especially prominent in younger, nonhospitalized patients. Among

5 Burch ADS, Cargill C, Frankenfield J, Harmon A, Robertson C, Sinha S, et al. “An anvil sitting on my chest”: What it’s like to have Covid-19. The New York Times. May 6, 2020.

6 Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, Fastenberg JH, Tham T. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):3–11. doi: 10.1177/0194599820926473.

567 adults who reported a loss of taste or smell in the prior month, 77% tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.7 Loss of both smell and taste was more strongly associated with antibody positivity than loss of taste alone. Dr. Tim Spector, one of the investigators in the COVID Symptom Study, noted that it took a few months for clinicians to recognize the diagnostic importance of anosmia, which was 10 times more predictive of COVID than any other single symptom.8

A wide variety of gastrointestinal and dermatologic symptoms were also reported. In data from the COVID Symptom Study, 17% of patients said they had experienced a rash.9 The rashes included hives; a diffuse papular, erythematous eruption; and reddish/purplish bumps on the fingers or toes, termed “COVID toes.” In 20% of cases, the rash was the only presenting symptom. COVID fingers and toes has been the most characteristic rash associated with COVID infection and has been reported in as many as 40% of cases.10

Symptoms have varied with age, disease severity, and underlying health. Dr. Mark A. Perazella, professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine, noted, “The problem is that it depends on who you are and how healthy you are. It’s so heterogeneous, it’s hard to say. If you’re healthy, most likely you’ll get fever, achiness, nasal symptoms, dry cough, and you’ll feel crappy. But there are going to be the oddballs that are challenging and come in with some symptoms and nothing else, and you don’t suspect Covid.”11

COVID symptoms were very unpredictable, as Robert Baird, a writer for The New Yorker, described in his own illness, “One of the strange and unsettling features of covid-19, as a disease, is that it appears to progress in a nonlinear fashion: people often feel bad, and then better, and then bad again.

7 Makaronidis J, Mok J, Balogun N, Magee CG, Omar RZ, Carnemolla A. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in people with an acute loss in their sense of smell and/or taste in a community-based population in London, UK: An observational cohort study. PLoS Med October 1, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003358

8 Menni C, Sudre CH, Steves CJ, Ourselin S, Spector TD. Quantifying additional COVID-19 symptoms will save lives. Lancet. 2020 Jun 20;395(10241):e107–e108.

9 Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, Sudre CH, Nguyen LH, Drew DA, et al. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential of COVID-19. Nature Medicine. 2020;26:1037–1040.

10 Daneshgaran G, Dubin DP, Gould DJ. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: An evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:627–639. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00558-4.

11 Parker-Pope T. The many symptoms of Covid-19. The New York Times. August 5, 2020. Accessed August 5, 2020. https://www.newyorktimes.com/

The possibility of a sudden downturn, it seems, is one that can’t be dismissed until you recover completely.”12

Mild to moderate COVID infection has generally been classified as one not requiring hospital admission. Over time it became clear that the duration of symptoms, even in mild to moderate COVID, was often longer than the 7–10 days reported in early studies. More than 90% of outpatients reported persistent symptoms 2–3 weeks after an initial positive test for COVID-19.13 Fever had resolved in 97%, but cough had not resolved in 43% and fatigue was still present in 35%. One-third of these patients initially reported dyspnea, and one-third of those were still short of breath at 2–3 weeks. Onequarter of those aged 18–34 years and one-half of those aged >50 years had not returned to their previous health at the 2–3-week interview.

The severity of pulmonary symptoms has been the most important factor in predicting disease severity. The initial public health advice was to stay at home unless you developed severe breathing difficulty. It wasn’t until later that we recognized how quickly and silently COVID pneumonia progressed. Dr. Richard Levitan, an emergency room physician, noted, “From a public health perspective, we’ve been wrong to tell people to come back only if they have severe shortness of breath. Toughing it out is not a great strategy.”14 In most hospitalized patients, shortness of breath did not develop until a median of 5–8 days after symptom onset. Dr. Leora Horwitz, associate professor of medicine at NYU, advised: “With Covid, I tell people that around a week is when I want you to really pay attention to how you’re feeling. Don’t get complacent and feel like it’s all over.”15 Dr. Charles A. Powell, director of the Mount Sinai-National Jewish Health Respiratory Institute, advised: “The major thing we worry about is a worsening at eight to 12 days—an increasing shortness of breath, worsening cough.”16

12 Baird RP. How doctors on the front lines are confronting the uncertainties of COVID-19. The New Yorker. April 5, 2020. Accessed October 9, 2020. https://newyorker.com

13 Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, Rose EB, Shapiro NI, Files DC, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network—United States, March–June 2020. MMWR. 2020 Jul 31;69(30):993–998.

14 Levitan R. The infection that’s silently killing coronavirus patients. The New York Times. April 20, 2020. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.newyorktimes.com/

15 Parker-Pope T. The many symptoms of Covid-19. The New York Times. August 8, 2020. Accessed September 2, 2020. https://www.newyorktimes.com/

16 Parker-Pope T. The many symptoms of Covid-19. The New York Times. August 8, 2020. Accessed September 2, 2020. https://www.newyorktimes.com/

It has been very difficult to determine whether any medications decrease the risk of severe COVID or hospitalization. There is evidence that monoclonal antibodies decrease the risk of severe COVID-19 and keep patients out of the hospital, but they have not been widely prescribed. As of January 1, 2021, less than 20% of the federal supply of monoclonal antibodies had been used at hospitals in the United States.17,18 One relatively small study found that early administration of high-titer convalescent plasma against SARSCoV-2 to mildly infected older patients reduced the risk of progression to severe respiratory disease.19

Dr. Janet Shapiro described her recurrent symptoms after recovering from what she thought was a mild COVID-19 infection: “However, after a few days, I felt worse, sensing that my heart rate was going fast even when I woke up. But I could not maintain the pace in the hospital, I could not breathe with my N95, I could not even stand for rounds. I was sent home to monitor my vital signs and with the instruction to rest and avoid stress, an impossible prescription for these times. The symptoms of chest tightness gradually subsided and, fortunately, the echocardiogram and laboratory parameters improved. What were the lessons of a relatively mild case for this physicianpatient? COVID-19 is really, really tragic, worse than we could have ever expected. I experienced what it is to feel one’s body, the difficulty of a breath, a fast heartbeat, the vagueness of feeling unwell and the fear it brings. This is what patients experience on a daily basis. No one is safe from illness.”20

Severe Infection, Hospitalization, and Death

During the early phases of the pandemic, approximately 5% of patients with COVID-19 infection developed severe symptoms, requiring hospitalization, with about one-third immediately admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU).21

17 McGinley L. Only one covid-19 treatment is designed to keep people out of the hospital. Many overburdened hospitals are not offering it. The Washington Post. December 31, 2020.

18 McGinley, L. Only one covid-19 treatment is designed to keep people out of the hospital. Many overburdened hospitals are not offering it. The Washington Post. December 31, 2020.

19 Libster R, Perez Marc G, Wappner D, Coviello S, Bianchi A, Braem V, et al. Early hightiter plasma therapy to prevent severe Covid-19 in older adults. N Engl J Med. January 6, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2033700. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2033700

20 Shapiro JM. Having coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1091. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3247.

21 Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the

The average interval of onset of symptoms to hospitalization was 7 days,22 and more than 80% of patients were hospitalized directly from home.23

Dr. Danielle Ofri described the alarming features of one of her first critically ill COVID-19 patients at Bellevue Hospital. “She’s already intubated, sedated, and paralyzed, but her temperature has started to jump the rails: first it’s 103.8, then 104.5, then 105.3. Three of us gingerly roll her to one side and attempt to slide an electric cooling blanket beneath her, without dislodging her breathing tube, arterial line, cardiac monitors, or I.V. drips. Her temperature hits 106.1. We cram specimen bags with ice as quickly as we can, tucking them into her armpits, under her neck, and between her legs. They turn to water almost on contact. Her temperature is now 106.9, and her pulse has soared to a hundred and seventy.”24

The mortality rate in hospitalized patients during the early months of the pandemic was 20%–30%. In Lombardy, Italy, 88% of hospitalized patients required mechanical ventilation and more than a quarter of the patients died.25 Of the 5,700 patients hospitalized in New York, 14% were treated in the ICU, 12% received mechanical ventilation, and 21% died.26 Almost 90% of patients who received mechanical ventilation died. In an early UK study of more than 20,000 hospitalized COVID-19 patients, 26% had died and another 34% were still receiving in-hospital care at the end of data collection.27 In another series of 1,000 hospitalized patients in New York,

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. February 24, 2020. 2020 Apr 7;323:1239–1242.

22 Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, O’Halloran A, Cummings C, Holstein R, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR. 2020;69:458–464.

23 Lavery AM, Preston LE, Ko JY, Chevinsky JR, DeSisto CL, Pennington AF, et al. Characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 patients discharged and experiencing same-hospital readmission–United States, March–August 2020. MMWR. 2020;69:1695–1699.

24 Ofri D. A Bellevue doctor’s pandemic diary. The New Yorker. October 1, 2020.

25 Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–1581. April 6, 2020. doi:10.1001/ jama.2020.5394.

26 Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. Apr 22. 10.1001/ jama.2020.6775.

27 Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, Hardwick HE, Pius R, Norman L, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: Prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985.

acute respiratory distress occurred in 35%, including 90% in the ICU, acute kidney injury in 34%, with 13% requiring dialysis, and new-onset cardiac arrhythmia in 9%.28 A systematic review of 25,000 patients from various countries with severe coronavirus disease found that 32% of patients with COVID-19 were admitted to the ICU and the mortality in those patients was 39% during the first few months of the pandemic.29

Dr. Christopher Chen described his own case of severe COVID-19 while hospitalized in the ICU as being “like dying in solitary confinement.” He continued: “Nights were the worst. That’s when the fevers were highest and my breathing was most labored. I felt like I was wasting away: covered in sweat, unable to bathe or shower, tied down by a web of wires, lines, and tubes and trying desperately to breathe. I got an inkling of what my heart failure patients experience when they cannot breathe due to fluid buildup in their lungs and feel like they are drowning from the inside out.”30

Dr. Levitan said, “Even patients without respiratory complaints had Covid pneumonia. When Covid pneumonia first strikes, patients don’t feel short of breath, even as their oxygen levels fall. And by the time they do, they have alarmingly low oxygen levels and moderate-to-severe pneumonia (as seen on chest X-rays). To my amazement, most patients I saw said they had been sick for a week or so with fever, cough, upset stomach, and fatigue, but they only became short of breath the day they came to the hospital. Their pneumonia had clearly been going on for days, but by the time they felt they had to go to the hospital, they were often already in critical condition.”31 At that stage patients often can’t maintain adequate oxygen supply and need to be intubated. As described by Dr. Dhruv Khullar, “A tube is snaked down a patient’s throat and into the lungs. All intubated patients are transferred to an I.C.U. The ventilator takes over the work of breathing; doctors treat what they can and hope for the best.”32

28 Argenziano MG, Bruce SL, Slater CL, Tiao JR, Baldwin MR, Barr RG, et al. Characterization and clinical course of 1000 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York; retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;369:m1996. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1996.

29 Abate SM, Ale SA, Mantfardo B, Basu B. Rate of intensive care unit admission and outcomes among patients with coronavirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020 Jul 10;15(7):e0235653.

30 Chen C. My severe Covid-19: It felt like dying in solitary confinement. STAT. August 28, 2020.

31 Levitan R. The infection that’s silently killing coronavirus patients. The New York Times. April 20, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2020. https://www.newyorktimes.com/

32 Khullar D. How to understand Trump’s evolving condition. The New Yorker. October 4, 2020. https://newyorker.com

Dr. Clayton Dalton, at Massachusetts General Hospital, described the downhill trajectory of COVID patients requiring intubation: “Ultimately, the ventilator is not a cure for covid-19; the machine can only provide support while doctors monitor and hope for improvement. Other patients continue to deteriorate, or perhaps just plateau with no sign of improvement, and so the I.C.U. team and family members must make a difficult decision about when to transition to end-of life care. There used to be a designated room for those conversations, adjacent to the unit, but now they take place on the telephone, or through Zoom or FaceTime. Once it’s agreed that further treatment is likely to be futile, the team shifts to comfort measures. Dialysis machines are powered down; I.V. pumps are disconnected; the vitals monitor is turned off, and its colored numbers disappear. Alarms go quiet, and the room falls silent. Morphine is given to ease pain and air hunger. Other medications decrease respiratory secretions, so that breathing can be as unencumbered as possible. Finally, the tube is removed, as delicately as possible, and the patient takes his or her last breaths.”33

As Dr. Clayton noted, most critically ill patients during the early stages of the pandemic were treated with mechanical ventilation. Subsequently, there was a greater focus on postponing mechanical ventilation and avoiding it altogether when possible. Moving patients onto their stomachs, so-called awake proning, was helpful, but not easy. “During the pandemic, proning has been shown to make a lifesaving difference for some patients; it allows the fluid in the lungs to redistribute itself, opening up new areas to oxygenation. But carefully flipping an unconscious, paralyzed patient can require as many as six people—nurses, assistants, therapists, and sometimes doctors, each gowned in P.P.E.—to coordinate their efforts, as though they are moving a large sculpture. In order for an I.C.U. to prone large numbers of patients each day, it must be fully staffed.”34 Awake proning and relative safety of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen have provided effective alternatives to mechanical ventilation.35

Large, university medical centers with ample critical care staff, equipment, and facilities were most capable of handling the sickest patients. In a study of 2,215 adults admitted to ICUs across the United States from March 4 to

33 Dalton C. The risks of normalizing the coronavirus. The New Yorker. May 27, 2020.

34 Nuila R. To fight the coronavirus, you need an army. The New Yorker. July 17, 2020.

35 Bos LDJ, Brodie D, Calfee SC. Severe COVID-19 infections: Knowledge gained and remaining questions. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Jan 1;181(1):9–11.

April 4, 2020, COVID-infected patients admitted to hospitals with fewer than 50 ICU beds had a threefold higher risk of death than those admitted to hospitals with more than 100 ICU beds.36 Dr. Daniela Lamas recounted the importance of expert hospital critical care: “While even the best possible treatment couldn’t save everyone, those who survived did so because of meticulous critical care, which requires a combination of resources and competency that is only available to a minority of hospitals in this country. And now, even as we race toward the hope of a magic bullet for this virus, we must openly acknowledge that disparity—and work to address it . . . we must also devote resources to helping hospitals deliver high-quality critical care. Maybe that will mean better allocating the resources we do have through a more robust, coordinated system of hospital-to-hospital patient transfers within each region. Maybe it means creating something akin to dedicated coronavirus centers of excellence throughout the country, with certain core competencies.”37

Gradually the COVID-19 mortality rate began to fall. In a later study, from March to August 2020, of 1,000 hospitals across the United States, 15% of hospitalized patients died, and of those discharged, 60% went home, 15% to a long-term care facility (LTCF), 10% to home health, and 4% to hospice (see Table 1.1).38 Readmission correlated with age >65 years, multiple comorbidities, and discharge to a skilled nursing facility or home care.

In a 60-day, follow-up study of 1,650 patients admitted to 38 hospitals in Michigan, 24% died and 15% of hospital survivors had been readmitted.39 More than one-half reported that they were mildly or moderately affected emotionally by the illness. In a Veterans Administration (VA) study of 2,200 patients hospitalized with COVID from March 1 to June 1, 2020, 31% were

36 Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, et al. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1436–1446. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596.

37 Lamas DJ. “If I hadn’t been transferred, I would have died.” The New York Times. August 4, 2020.

38 Lavery AM, Preston LE, Ko JY, Chevinsky JR, DeSisto CL, Pennington AF, et al. Characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 patients discharged and experiencing same-hospital readmission—United States, March–August 2020. MMWR. 2020;69:1695–1699.

39 Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. November 11, 2020. doi.org/10.7326/ M20-5661.

Table 1.1 Characteristics of Patients Discharged after Severe COVID-19 Infection

Modified from Lavery AM, Preston LE, Ko JY, Chevinsky JR, DeSisto CL, Pennington AF, et al. Characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 patients discharged and experiencing same-hospital readmission. United States, March–August 2020. MMWR. 2020;69:1695–1699.

treated in the ICU and 18% died.40 Twenty percent of the discharged patients were readmitted within 60 days and 10% died.

The hospital mortality rate from COVID-19 decreased further during the summer of 2020. Mortality in 4,700 hospitalized patients in New York City dropped from 33% in April to 2% in the late June 2020 (Figure 1.2).41 In the United Kingdom the 30-day mortality of 30%–40% for people admitted to critical care in April 2020 dropped to 10%–25% for those admitted in May 2020.42 Dr. John Dennis, a lead investigator of that UK study, noted, “In late March, four in 10 people in intensive care were dying. By the end of June, survival was over 80 percent. It was really quite dramatic.”43

The decreased mortality was, in part, related to a decrease in the age of hospitalized patients. The median age of all confirmed COVID infections in the United States was 46 years on May 1, 2020, compared to 38 years at the

40 Donnelly JP, Wang XQ, Iwashyna TJ, Preswcott HC. Readmission and death after initial hospital discharge among patients with COVID-19 in a large multihospital system. JAMA Network. 2021;325(3):304–306. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21465.

41 Horwitz LI, Jones SA, Cerfolio RJ, Francois F, Greco J, Rudy B, et al. Trends in COVID-19 risk-adjusted mortality rates. J Hosp Med. October 23, 2020. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3552.

42 Dennis J, McGovern A, Vollmer S, Mateen BA. Improving COVID-19 critical care mortality over time in England: A national study, March to June 2020. medRxiv. Accessed March 12, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.20165134

43 Rabin RC. Death rates have dropped for seriously ill Covid patients. The New York Times. October 29, 2020.

Figure 1.2. Mortality (%) of Hospitalized Patients Dying from COVID-19 in New York City, March–August 2020.

From: Horwitz LI, Jones SA, Cerfolio RJ, Francois F, Greco J, Rudy B, et al. Trends in COVID-19 risk- adjusted mortality rates. J Hosp Med. October 23, 2020.

end of August.44 The median age for the hospitalized patients decreased from 67 years in March 2020 to 49 years in June. In Houston, Texas, patients hospitalized between May 16 to July 7, 2020, compared to those hospitalized between March 13 and May 15, 2020, were younger, had a lower burden of comorbidities, and a decrease in the case fatality rate (CFR).45

The decrease in CFR was also, in part, related to improved care, including treatment for COVID-related hypercoagulability. Thrombotic events were found in more than one-third of COVID-hospitalized patients.46 Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) typically occurred 4–10 days after hospitalization, and one-third of DVTs were associated with pulmonary embolism.47

44 Boehmer TK, DeVies J, Caruso E, van Santen KL, Tang S, Black C, et al. Changing age distribution of the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, May–August 2020. MMWR 2020;69:1404–1409. http://dx.doi.org/0.15585/mmwr.mm6939e1

45 Vahidy FS, Drews AL, Masud FN, Schwartz RL, Askary B, Boom ML, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 patients during initial peak and resurgence in the Houston metropolitan area. JAMA. 2020;324:998–1000. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.15301.

46 Piazza G, Morrow DA. Diagnosis, management, and pathophysiology of arterial and venous thrombosis in COVID-19. JAMA. November 23, 2020.

47 Gomez-Mesa JE, Galindo S, Montes MC, Munoz Martin AJ. Thrombosis and coagulopathy in COVID-19. Curr Probs Cardiol. 2021 Mar;46(3):100742. doi: 10.1016/ j.cpcardiol.2020.100742.