Constitutionalism and the Paradox of Principles and Rules

Between the Hydra and Hercules

MARCELO NEVES

3

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Marcelo Neves 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Crown copyright material is reproduced under Class Licence Number C01P0000148 with the permission of OPSI and the Queen’s Printer for Scotland

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020952611

ISBN 978–0–19–289874–6

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192898746.001.0001

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

To Renato, Bernardo, and Elvira, with gratitude

Preface

In 2003, upon returning to Brazil after several years of research and teaching activities in Europe, I came across a wide audience surrounding the debate on principles and rules, balancing and optimization, theory of principles, constitutionalization of law, and related issues. Somewhat surprised, I observed that this language was not confined to the legal and constitutional theory but it expanded on legal doctrine and judicial practice without limits.

I tried to be attentive to the discussion. I started to observe that, with some exceptions, it was again an uncritical borrowing from foreign theoretical and doctrinal constructions without the selective assessment of a legally and constitutionally proper reception. It largely consisted in trivializing principle-based models consistently developed under legal contexts that are very different from the Brazilian experience. On the one hand, invoking (moral and legal) principles was presented as a panacea to solve all the ills of Brazilian legal and constitutional practice. On the other hand, the principle-overestimating rhetoric served the removal of clear and ‘complete’ rules in order to cover decisions oriented towards the satisfaction of particularistic interests. Thus, both genuinely idealistic and shrewdly strategic lawyers were capable of learning how to use successfully the pomp of principles and weighing, the trivialization of which lent to any argument, even the most absurd, a bit of respectability. All this, it seems to me, occurred to the detriment of a constitutionally consistent and socially adequate legal adjudication.

This situation has not changed substantially over the last few years. The judgment of the Direct Action of Unconstitutionality (ADI) No. 4,638/DF by the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court on 2 February 2012 provides a good example: a Justice appealed to the dignity of the human person and Ronald Dworkin’s authority to justify maintaining in force provisions of the Organic Law of National Judiciary (LOMAN, issued by the military authoritarian government 1964–1985) which required secret trials in any case of judgment of a judge (Complementary Law No. 35/1979, Article 27.2 and 27.6, Article 45, Article 52.6, and Articles 54 and 55); he did not consider that this plea vehemently opposed clear constitutional rules introduced by Constitutional Amendment No. 45/2004 (Brazilian Federal Constitution, Article 93.IX and 93.X), which precisely aim to remove one of the privileges of the magistrates.

The judgment of the Direct Action of Unconstitutionality (ADI) No. 1856/RJ by the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court, on 26 May 2011, offers another example, somewhat more odd and unreasonable (the case was already being solved on the basis of the constitutional rule that forbids ‘all practices which . . . subject animal to cruelty’—Article 225.1.VII of the Brazilian Constitution): three justices call for ‘human dignity’ to characterize the unconstitutionality of a State statute that allows cockfighting.

Over time I have noticed that the issue could not be dealt with only in terms of uncritical and unreflexive reception of foreign legal and constitutional theory models in Brazil because it has involved a fascination with the rhetoric of the principles and balancing on a global scale. Thus I decided to challenge the worldwide dominant models of the theory of principles, critically focusing on the problematic Brazilian case only in Chapter 4 in this book.

Nevertheless, this study is not simply proposing a ‘demystification’ or, to use a fashionable term, a ‘deconstruction’ of the legal and constitutional theory, doctrine, and practice that, under the heading of principle, balancing, optimization, and related labels, have become not only dominant but also stifling over the three last decades. Despite taking as my object of criticism the abuse of principles in legal and constitutional theory, doctrine, and practice, I take the constitutional principles seriously, pointing to their complementary relationship and tension with the rules. Along this line, I shall face theories that before and today serve as a paradigm for discussion around legal or constitutional principles and rules, discussing them critically in order to offer an alternative theoretical model.

After giving some lectures on the subject and having the initial intention to write a paper on the issue, I decided, finally, on a more comprehensive project, writing a monograph on the theme, which resulted in this book. Its first edition was published in Portuguese in Brazil (São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2013). This English edition is not a mere translation. I revised many parts of the text and added new remarks, notes, and bibliographical references to the third Brazilian edition of 2019. I aimed to update the study invoking some new literature and presenting some explanations on issues that were not properly addressed earlier.

For the preparation and publication of the Brazilian edition and this English edition, I counted on the support of some institutions and people, the mention of which serves as a record of my gratitude.

In late June and early July 2010, I worked as a visiting research fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law in Heidelberg. This research stay was instrumental for the development and

completion of the first edition. In that time, I could again enjoy the excellent conditions of study offered by the Institute and participate in fruitful discussions with colleagues of various nationalities. I am grateful for the invaluable support that was given to me by the Director of the Institute, Armin von Bogdandy, and his colleagues and assistants.

During the period in which I was writing the first draft, Virgílio Afonso da Silva, Regis Dudena, Thales Costa, and André Rufino do Valle proposed and sent me relevant theoretical, doctrinal, and case-law materials. To these colleagues I register here my vote of thanks. I also am grateful to Vinicius Poli, Pedro Henrique Ribeiro, Paulo Leonesi Maluf, Octaviano Padovese, and Helena Bittencourt for the revision and proofreading of the first Brazilian edition.

This English edition is the result of two research stays abroad, first as a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Adam Smith Foundation in the College of Social Sciences at the University of Glasgow in 2014, second as a Senior Research Scholar at Yale Law School in 2015. I wish to thank Emilios Christodoulidis, Rosa Greaves, and Marco Goldoni for the enlightening conversations during my stay in Glasgow. I am also very grateful to Robert Post, Paul Kahn, Bruce Ackerman, Daniel Markovits, William Eskridge, and Alec Stone Sweet for opening the door for me to the excellent scholarly atmosphere at Yale.

I translated myself a number of extracts from foreign theoretical and doctrinal works as well as passages from foreign case law and legislation. In the bibliographical references I have mentioned any acceptable English translations located. The footnotes to many citations also include references to the corresponding pages in the English translations available to me. In some cases I have adapted these translations where appropriate. I am very grateful to Klébert Machado and Edvaldo Moita for the linguistic revision of this English version.

In drawing up the English edition, I was again fortunate to receive the inestimable encouragement of Elvira, Bernardo, and Renato. Hence the dedication!

2.

Abbreviations

ADI Ação Direta de Inconstitucionalidade [Direct Action of Unconstitutionality] (Brazil)

ADPF Arguição de Descumprimento de Preceito Fundamental [Claim of Non-Compliance with a Fundamental Precept] (Brazil)

BFC Brazilian Federal Constitution

BVerfGE Entscheidungen des Bundesverfassungsgerichts [Decisions of the Federal Constitutional Court; official compilation of this German Court; the numbers placed after the abbreviation refer to the volume and first page of the judgment respectively]

cf. confer [compare]

DJ Diário da Justiça [Law Reports; official compilation of judgments handed down by Brazil’s higher federal courts]

DJe Diário da Justiça eletrônico [electronic version of Law Reports; official compilation of judgments handed down by Brazil’s higher federal courts]

ed. editor

edn edition

eds editors

Engl. trans. English translation

esp. especially

Ext. Extradição [Extradition] (Brazil)

ff. following pages

HC Habeas Corpus (Brazil)

LOMAN Lei Orgânica da Magistratura Nacional [Organic Law of National Judiciary] (Brazil)

Mercosur Mercado Común del Sur [Southern Common Market]

MS Mandado de Segurança [Writ of Mandamus] (Brazil)

p. page

pp. pages

RE Recurso Extraordinário [Extraordinary Appeal] (Brazil)

STF Supremo Tribunal Federal [Federal Supreme Court] (Brazil)

STJ Superior Tribunal de Justiça [High Court of Justice] (Brazil)

TFP Tradition, Family and Property

TP Tribunal Pleno [Plenary; Brazilian Federal Supreme Court] vol. volume vols volumes

Introduction

Between Herculean Rules and Hydra-like Principles

According to the mythological narrative, Hercules,1 in his second of twelve labours performed on behalf of his cousin Eurystheus, King of Mycenae, confronted the Hydra of Lerna. Dwelling in a swamp near Lake Lerna, in Argos, the Hydra was a monstrous snake-like, multi-headed beast (sometimes described as having human heads),2 which destroyed herds and harvests, and whose breath was lethal to those who neared her. Hercules fought the Hydra with flaming arrows or, according to a variant narrative of the legend, by cutting off her heads with a sword. The great challenge of this task stemmed from the fact that the Hydra regenerated her multiple heads every time one of them was cut off. To overcome this difficulty, Hercules resorted to his nephew Iolaus, asking him to set the nearby woods on fire and bring him firebrands to cauterize the open wounds resulting from the beheadings. Thus, after Hercules had cut off each head, Iolaus burned the Hydra’s open neck stumps. The cauterization prevented the regrowth or regeneration of new heads. Finally, with the help of Iolaus, Hercules hewed down the principal head, previously thought to be immortal, and crushed it with a huge rock, under which he buried it. This way, Hercules slayed the Hydra and successfully performed his second labour.3 The metaphorical reference employed in the subtitle of this book, Between the Hydra and Hercules, designates a touchstone that shall guide this work. In my approach, I reverse the dominant perspective on principles and rules stemming from Ronald Dworkin’s work. According to Dworkin, Judge Hercules, a regulative ideal, is one who is able to identify the principles suitable for solving a case, allowing for ‘a single right answer’ or, at the very least, the best judgment of it.4 In this sense, it can also be said that the principles are Herculean.

1 Hercules, in Roman mythology, corresponds to Heracles in Greek mythology.

2 The sources vary in regard to the number of heads (from five or six to one hundred, according to Grimal, 1951, 191; Kury, 2003, 183). Venit (1989, 102 and 104) refers to nine.

3 Cf. Grimal, 1951, 187–203 (esp. 191–2), 215, 232; Kury, 2003, 180–7, esp. 183, 192–3, 197; Venit, 1989.

4 Dworkin, 1978, 105 ff., 279 ff.; 1986, esp. 239 ff., 380–1; 1985, 119 ff.; 2006a, 41–3, 54 ff. I return to this topic in Chapter 2 section 3.

Constitutionalism and the Paradox of Principles and Rules. Marcelo Neves, Oxford University Press. © Marcelo Neves 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192898746.003.0001

It is well known that Dworkin’s thesis arose as a criticism of the analytical positivism posited by Hart, according to whom the legal order, defined as a system composed of primary rules of conduct and secondary rules of organization, provides the judge with room for discretion, in which the choice of one of the alternatives offered does not necessary come under any existing rules, implying the ‘open texture of law’.5 To Dworkin, cases that cannot be settled by rules ought to be decided by morally supported legal principles, which, according to this perspective, would prevent any discretionary room or power for Judge Hercules.6

In this book, an opposite view is offered: principles have a Hydra-like character, whereas rules are Herculean. This perspective is not related to the existence or inexistence of discretion, a theme to which I will return in the course of this work. Rather, it concerns the flexibility that principles confer to the legal system by increasing the possibilities for argumentation. According to this understanding, principles act as a stimulus to the construction of arguments capable of leading to suitable solutions to thorny legal cases, without restricting such solutions to discretionary options. Owing to their plurality, or—expressed metaphorically—their ‘multi-headed’ features, principles improve the argumentative process among the concerned judges, parties, and

5 Hart, 1994, 91 ff., 124 ff., 145–7, 279 ff.; Dworkin, 1978; 16 ff., 46 ff. Although derived from another theoretical perspective, Hart’s notion of the ‘open texture of law’ is analogous to Kelsen’s conception of ‘law to be applied as a frame within which several applications are possible’ (Kelsen, 1960, 348–9 (Engl. trans. 1967, 350–1)). It lies outside the scope this book to engage in the ‘Hart–Dworkin Debate’, much less to offer a review of the extensive literature surrounding it. In this regard, see the critical review presented by Shapiro (2007). Although Shapiro (ibid., 50) maintains that ‘reports of the demise’ of this debate ‘would be greatly exaggerated’, he points out that ‘the Hart–Dworkin Debate is indeed past its intellectual sell-by date’. Shapiro also presents the following thesis: ‘Contrary to Dworkin’s interpretation, Hart never embraced the model of rules, either explicitly or implicitly’ (ibid , 30). Indeed, Shapiro recognizes that ‘Hart accepts some responsibility for the confusion’ (ibid , 51, note 4), quoting the following passage of Hart’s Postscript: ‘Much credit is due to Dworkin for having shown and illustrated [the] importance [of legal principles] and their role in legal reasoning, and certainly it was a serious mistake on my part not to have stressed their non-conclusive force’ (Hart, 1994, 263). However, he emphasizes that Hart ‘goes on to disavow Dworkin’s interpretation of his view’ (Shapiro, ibid ), quoting the continuation of this passage: ‘But I certainly did not intend in my use of the word “rule” to claim that legal systems comprise only “all-or-nothing” [standards] or near-conclusive rules’ (Hart, 1994, 263; the word ‘standards’ was added by Shapiro, who also removed ‘intend’and ‘to’).

6 In Dworkin’s language, it is not about discretion in a weak sense but in a strong sense: ‘Sometimes we use “discretion” in a weak sense, simply to say that for some reason the standards an official must apply cannot be applied mechanically but demand the use of judgment. . . Sometimes we use the term in a different weak sense, to say only that some official has final authority to make a decision and cannot be reviewed and reversed by any other official. . . I call both of these senses weak to distinguish them from a stronger sense. We use “discretion” sometimes not merely to say that an official must use judgment in applying the standards set him by authority, or that no one will review that exercise of judgment, but to say that on some issue he is simply not bound by standards set by the authority in question.’ It is in this strict sense that Dworkin criticizes ‘the positivists’ doctrine of judicial discretion’, which he defines in the following terms: ‘That doctrine argues that if a case is not controlled by an established rule, the judge must decide it by exercising discretion.’ But he does warn: ‘The strong sense of discretion is not tantamount to license, and does not exclude criticism’ (Dworkin, 1978, 31–3).

other stakeholders, opening it to manifold starting points. Observers from very diverse perspectives are motivated by principles to take an active part in the argumentative practice directed to legally ground the settlement of a juridical problem. In this regard, in today’s complex society principles promote the expression of dissent on legal issues and, at the same time, serve procedural legitimation by absorbing dissent.7

However, principles alone do not settle the cases to which they are intended to be applied. The resolution of legal cases in a constitutional state depends upon rules. If the case is a ‘routine’ or an ‘easy’ one, it is clear that it does not entail any greater difficulties, as in this case the argumentative chain is practically reduced to the semantic determination of the meaning of provisions and the subsequent subsumption of the case under a rule. The question grows in significance when the relationship between rules and principles is considered to be relevant for the resolution of a case. In this regard, rules, although being demarcated in light of or even derived from principles, serve to domesticate the latter, enabling a definitive closure of the argumentative process surrounding the concrete interpretation and application of law. It is in this sense that rules are Herculean. Whereas principles open the process of legal and constitutional concretization,8 instigating new argumentative problems in a Hydra-like manner, rules tend to close it, absorbing and dissipating the uncertainty that characterizes the initial stage of the procedure of norm application. The uncertainty is then qualified, and the complexity becomes relatively structured (or structurable) by virtue of the legal principles because they provide certain contours and reference points—anchored in normative expectations present in society and in those directly involved in the process—that are useful for the discussion aimed at the resolution of a case. In sequence, only rules are capable of enabling the transformation from the uncertainty of the starting point to the certainty drawn from the decision or ruling of a case.9 Only rules can lead

7 See Neves, 2000, 108 ff

8 In this book I shall employ the concept of legal or constitutional concretization in roughly the same sense it has been used in the German constitutional and legal theory (see esp. Hesse, 1969, 25 ff.; F. Müller, 1995, 166 ff.; 1994; 1990a; 1990b; Christensen, 1989, 87 ff.). It refers to a process that goes from abstract constitutional or legal standards to the concrete ought-decision or ought-judgment (ruling) of a case, involving the interpretation of norm texts and of facts, and finishing with the application of law to a specific case. It concludes not only with a court adjudication or decision, but also with legislative and executive interpretations (Tushnet, 2008, 79) as well as arbitration awards and legal transactions or the application of law by private acts (cf. Kelsen, 1960, 261 ff. (Engl. trans. 1967, 256 ff.)). However, legal or constitutional concretization excludes both the mere factual observance or compliance and the mere enforcement of a ruling applying legal or constitutional standards. I shall refer to these two factual dimensions using the phrases ‘constitutional’ and ‘legal realization’ or ‘efficacy’.

9 Of course, certainty is only reached in a case with the final ruling, which corresponds to a ‘decision norm’ (in the sense proposed by F. Müller, 1994, esp. 264; 1990a, esp. 48–that is, an ought-judgment of a legal case). This kind of norm is typically an ‘individual norm’ in Kelsen’s sense (Kelsen, 1960, esp. 20,

to a reduction in complexity or to a selection capable of determining the case solution.

These remarks should not prevent us from seeing the other side of the coin. Rules alone, due to being more bound to concrete situations, are hardly proper for absorbing the high complexity of the so-called hard cases.10 Owing to their restricted degree of flexibility and tendency to Herculean rigour, rules have to be linked to principles in order to tackle highly complex problems. In the course of the process of normative concretization, legal principles convert the unstructured complexity of the legal system’s environment (values, moral representations, ideologies, efficiency models, etc.) into a complexity capable of being structured from the normative-juridical point of view, while legal rules selectively reduce the complexity that through principles has become capable of being structured, transmuting it into a legally structured complexity that makes it possible for a case to be resolved.

Rules and principles are two normative poles essential to the process of legal and constitutional concretization, nurturing each other circularly in the argumentative chain that leads up to the case decision. There is no linear hierarchy between them. On the one hand, rules depend upon being marked out or constructed from principles. On the other hand, the latter only gain practical significance if they are connected with rules providing them with density and relevance for settling a case. This is not, in anyway, a sort of harmonic relationship. It is rather a paradoxical relation, as will be shown especially in the course of the third chapter. Analogous to the relationship between the Hydra and Hercules in the mythological episode, principles and rules relate to one another in a conflicting way.

The tendency to overestimate principles at the expense of rules makes the degree of uncertainty too high and can degenerate into an uncontrollable insecurity linked with the breaking of the consistency of the legal system itself and, thus, with the destruction of its operating boundaries. Conversely, a tendency to overvalue rules to the detriment of principles makes the legal system excessively rigid to face complex social problems, in the name of a legal consistency

85, 242, 265 (Engl. trans. 1967, 19, 80, 236–7, 260–1); 1945, 37–8 and 134 ff.), but can also have general effects, such as rulings in cases concerning the abstract judicial review of legal standards (e.g. the abstract control of statutory rules). However, the uncertainty reappears at the level of enforcement, as one still has to interpret the text of the judicial decision. The problem then garners new contours, taking it beyond the scope of this book.

10 See Dworkin, 1978, 81–130, who distinguishes them from the ‘weak cases’; Aarnio, 1987, 1 ff., who contrasts them to the ‘routine cases’. Carrió (1986, 55–61) distinguishes similarly between ‘marginal cases’ and ‘typical cases’. Dworkin himself (1986, 354) qualifies the difference between hard and weak cases by taking into account the temporal and personal variables.

incompatible with the social adequacy of law. Therefore, with respect to the relation between rules and principles, one is confronted at the argumentative level with the question of overcoming or processing the paradox of legal consistency and social adequacy in each concrete case, which is, in general terms, the paradox of justice as ‘a formula for contingency of the legal system’.11

In this introductory chapter, it is worth emphasizing that the discussion to follow will have a specific focus, being necessary to provide some background explanations. First of all, it must be noted that the term ‘principle’ can be both ambiguous and vague.12 It is not uncommon to incur ‘fallacies of ambiguity’,13 discussing in a nonsensical manner the same term or expression as though it was always referring to the same concept. Of course, there are terms and expressions that have such enormous seductive power in themselves that merely resorting to them serves the rhetorical purposes of those employing them, irrespective of whatever meaning is assigned to them. The term ‘principle’, like the expression ‘constitution’, has acquired this status.14 In turn, it is obvious that every conceptual discussion implies the semantic delimitation of the corresponding terms, which makes the problem somewhat circular. It is fundamental, however, that the questions on concepts and concerning the definition of terms or expressions be treated in view of the theoretical or practical problem one intends to deal with or resolve. It is in this sense that I propose a preliminary semantic delimitation in order to specify the problem I intend to address.

In ancient philosophy, principles refer to starting points, foundations, or ‘causes’ of any process. Dating back to Anaximander and continuing through Plato, this notion of principle was comprehensively examined by Aristotle, who lists several meanings of ‘principle’ (‘beginning’), leading up to the conclusion: ‘It is a common property, then, of all “beginnings” to be the first thing from which something either exists or comes into being or becomes known.’15 In modern philosophy, Kant, by dealing with ‘reason in general’, points out the ambiguity of the term ‘principle’: ‘Every universal proposition, even if it is

11 Luhmann, 1993, 214 ff. (Engl. trans. 2004, 211 ff.).

12 About its various uses in the philosophical tradition, from the standpoint of existence, logical point of view and in the normative sense, see Lalande, 1968, 827–9, who quotes a suggestive passage of Condillac, 1831, 109: ‘Principle is synonymous with beginning, and was early used with this meaning; but then, by virtue of use, it was employed mechanically, by habit and without being assigned to it any ideas’ (Lalande, 1968, 827). Condillac (1931, 109) adds: ‘and we had some principles that are the beginning of nothing.’ Regarding the various meanings of ‘principle’ in general and ‘legal principle’ in particular, see Carrió, 1970, 32 ff.; Atienza and Manero, 1998, 3–4.

13 Copi, 1961, 73 ff.

14 In regard to ‘constitution’, see Neves, 2009, 1–6 (Engl. trans. 2013, 5–8).

15 Aristotle, 2003, 211, Book V, I.3.

taken from experience (by induction), can serve as the major premise in a syllogism; but it is not therefore itself a principle.’16 Departing from this common use, Kant refers to the notion of ‘principles of pure understanding in themselves’, which alone are entitled to be called principles (‘It is properly these that I call principles absolutely’) insofar as they are purely rational (a priori).17 They are mentioned by him when he defines reason as ‘the faculty of the unity of the rules of understanding under principles’.18 In the study of morals and ethics, in turn, Kant employs the term ‘principles’ to distinguish between a ‘maxim’ as a subjective principle of willing or action and the practical (moral) ‘law’ as an objective principle of the will or action, which would be valid for all rational beings, ‘if reason had complete control over the desiderative faculty’.19 In these terms, ‘maxim’ contains the practical rule according to which the subject acts in conformity with his own conditions, whereas the ‘law’ is the objective principle according to which every rational being ought to act. 20

In modern sciences, in which the concept of ‘principles’ has largely lost its significance, the term has also been used to indicate the basic premises of a given field of knowledge. In the area of natural sciences, this term refers to certain empirical propositions that, by means of (suitable, useful) conventions, are precluded from experimental control, as pointed out by Poincaré.21 In the realm of mathematics, principles were considered, in general, as premises of a demonstration and were conceptually substituted by axioms and postulates.22 Somehow, these varied concepts have been disseminated across several areas of theory and practice, with much imprecision and variation in meaning. By employing the term ‘principle’, one often intends both to denote the basic premises of some realm of knowledge or the social world in general and to invoke universal and ultimate norms. Finally, it is commonly used to refer to the ordering and unifying function performed by some norms for a given system or order, most notably the law.23 Instead of using the vague term ‘principles’ to indicate such a broad conceptual family, I would rather call them, depending

16 Kant, 1990 [1781A/1787B], vol. 1, 312 [A 300/B 356] (Engl. trans. 1998, 387–8).

17 Kant, 1990 [1781A/1787B], vol. 1, 313 [A 301/B 357–8] (Engl. trans. 1998, 388). However, he adds: ‘Nevertheless, all universal propositions in general can be called principles comparatively’ (1990 [1781A/1787B], 313 [A 301/B 358] (Engl. trans. 1998, 388)).

18 Kant, 1990 [1781A/1787B], vol. 1, 314 [A 302/B359] (Engl. trans. 1998, 389).

19 Kant, 1965 [1785/1786], 18–19, 42 [400-1/420-1] (Engl. trans. 2012, 15–16, 33–4). The objective principle or practical law is related to the categorical imperative in Kant’s work (1965 [1785], 20, 34–5, 42 [402, 414, 420–1] (Engl. trans. 2012, 17, 28, 33–4)).

20 Kant, 1965 [1785], 42 [420–1] (Engl. trans. 2012, 33–4).

21 Poincaré, 1905, 207–11. However, Poincaré warned that, ‘if a principle ceases to be fecund, experience without directly contradicting it will nevertheless have condemned it’ (209).

22 Abbagnano, 1961, 678.

23 Cf. Pascua, 1996, 11.

on the context, the ‘premises’ or ‘starting points’ of an argumentative process or chain, the ‘postulate’ of a field of knowledge, the ‘basic laws’ of logic, the allegedly ‘fundamental’ or ‘presupposed norms’ in the sphere of law or ethics and morality, or finally the ‘binary codes’ guiding the reproduction of communication systems.24

Employing the concept of principles in the domain of law, in the broad terms of the discussion around ‘general principles of law’, is not the main goal of this work either. This is rather a philosophical discussion in which the term is used to distinguish between those who claim that the general principles of law are derived from natural law and those who hold the legal positivist view on these principles.25 This debate has its home in the context of the general theory of law in the Euro-continental tradition whenever the issue of supplying the gaps in the law is the matter under consideration, prompting the question of whether the general principles of law become valid through self-integration or hetero-integration. In this regard, the very ‘Introductory Statute to the Norms of Brazilian Law’ provides that the judge, besides having the competence to invoke analogy and customs, is authorized to decide in accordance with the general principles of law if the statutory law is silent on the matter of the case brought before the court.26 The hetero-integration thesis maintains that the general principles of law are supra-positive; the self-integration thesis asserts that they belong to the respective positive order, being inducted from the set of legal norms through hermeneutic activity.27 As there is a channel of internal reception expressly established by a statute, it seems that this question is not relevant in the Brazilian context. Strictly speaking, the so-called general principles of law, which are referred to in both statutory law and case law of several legal orders, are maxims consolidated in the Western legal tradition, especially from Roman law, with some of them constituting principles in a strict sense and others consisting of common rules. In the event that a law is silent or has gaps on a specific issue, principles are internalized in the legal system through hetero-integration in the concrete situation, or if they already belong implicitly

24 Here I refer to binary codes in Niklas Luhnann’s terms: ‘Functional systems are never teleological systems. They refer each operation to a bivalent distinction—to the binary code—thus ensuring that a follow-up communication is always possible for switching to the opposing value. . . Binary codes are in a strict sense forms, which is to say two-sided forms that facilitate switching from one side to the other, from value to opposing value and back by distinguishing themselves as forms from other forms. For example: true/false; beloved/unloved; having property/not having property; passing exams/failing exams; exercising authority/being subject to authority, and so forth’ (Luhmann, 1997, vol. 2, 749–50 (Engl. trans. 2013, 91)).

25 See Pascua, 1996, 11 ff.

26 ‘Art. 4. If the [statutory] law is silent, the judge shall decide according to analogy, customs, and general principles of law.’

27 See, respectively, Bobbio, 1960, 179–84; Betti, 1949, 51–2, 205 ff.

or explicitly to the legal order, it only takes self-integration for their application to the case resolution. It is clear that one might also appeal to these maxims at the constitutional level if there are gaps in the constitutional clauses, but this issue is secondary to the theme addressed in this work.

The focus of the present study is on the relation between constitutional principles and constitutional rules. On the one hand, values and moral criteria will be taken into account only insofar as they are integrated into the legal order via one of these two types of constitutional norms. On the other hand, infra-constitutional principles and rules will only be considered if their understanding, interpretation, and application shed light on or serve to the interpretation and application of constitutional principles and rules.

Moreover, even within the specific scope of the debate around the relation between constitutional principles and rules, this study does not intend to exhaust the subject or to offer an encyclopaedic review. Instead, it will concentrate critically on the legal-constitutional debate that has developed since the 1970s around constitutional principles and rules, in particular in regard to Ronald Dworkin’s and Robert Alexy’s works, in order, on this basis, to present an alternative model and to point out the limitations and misunderstandings of the reception of the theory of legal principles in the Brazilian constitutional jurisprudence and constitutional case-law.

In Chapter 1, I shall briefly analyse the main theoretical currents that have addressed the matter of legal principles and rules before the explosion of the theory of constitutional principles. At this point, the general theory can hardly be distinguished from the constitutional conception of principles and rules.

In Chapter 2, I will initially examine the philosophical background of the dominant model for understanding constitutional principles and rules. Thereafter, I shall analyse this model, paying special attention to two of its trends that build on the works of Dworkin and Alexy.

In Chapter 3, I will present a model for distinguishing between constitutional principles and constitutional rules, emphasizing that it concerns a legal-doctrinal difference that emerged with modern constitutionalism. In this context, principles will be defined as reflexive mechanisms in relation to rules, and the circular connection between them will become the focus of my analysis. I will also discuss the performance of principles and rules in the process of constitutional concretization as well as point out the requirement of a constitutional principle theory adequate to the complexity of contemporary society, even in the context of transconstitutionalism.

In Chapter 4, I shall review the use and abuse of principles in the Brazilian constitutional doctrine and practice. First, the problem of doctrinal fascination

will be addressed, pointing out theoretical and jurisprudential mistakes. Second, I will make some critical comments on confused constitutional practices related to principles, considering some cases judged by the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court.

As a final comment, I will return to the metaphor expressed in the subtitle, in order to consider what type of judge is best prepared to face and overcome the paradox of the relation between principles and rules in each concrete case: Judge Hercules or Judge Hydra? The answer will ultimately be neither of them.

1 From Classic Distinctions Between Legal Principles and Rules

1. Norms Between Texts and Facts

When discussing the distinction between principles and rules, in terms both of the general theory of law and of constitutional doctrine, the debate turns to characterizing types of norms, even to ascertaining whether both categories are covered by the concept of norm. Therefore, the first step is to remove the confusion between norm and normative text. The terms ‘norm formulation’,1 ‘normative provision’, and ‘normative statement’2 may also be used to distinguish the linguistic form through which a norm is expressed by positive law, particularly the written law. To this end, I will use the expressions ‘normative text’ in general or ‘norm provision’ in particular,3 leaving ‘normative statement’ to refer to the linguistic expression of an interpretative or a legal-doctrinal proposition that is intended to describe or determine the semantic content of a norm.4 (Additionally, the term ‘normative statement’—rather than ‘normative provision’—will sometimes be employed to refer to the assertion of a derivative legal or constitutional norm, i.e. a norm indirectly attributed to a legal or constitutional text by the officer or body in charge of its legally binding interpretation-application.) Here, it is about distinguishing between the levels of the signifier and the signified.5 The connection between these two levels

1 Von Wright, 1963, 93, 96–7; Aarnio, 1990, 181–2; 1997b, 19; Canotilho, 1998, 1075–6; Schauer, 1991, 62–4, who distinguishes rule from rule formulation.

2 See Alexy, 1986, 54 ff. (Engl. trans. 2002, 21 ff.), who distinguishes between a constitutional rights norm and a constitutional rights normative statement; Canotilho, 1998, 1077–80; Guastini, 2010, 35 ff.; 1998a, 15 ff.; 1993, 17 ff.; 1992, 15 ff.

3 On the distinction between norm and normative text, see, among many, F. Müller, 1994, esp. 147–67 and 234–40; 1995, 122 ff.; 1990a, 126 ff.; 1990b, esp. 20; Christensen, 1989, 78 ff.; Jeand’Heur, 1989, esp. 22–3; Möllers, 2015, 278 ff. (with qualifications); Grau, 2009, esp. 84–6; P.B. Carvalho, 2008, 126–31; Tarello, 1980, 101 ff., who distinguishes norms from normative documents.

4 Aarnio, when distinguishing between interpretation in the broad sense, which refers to the various possible meanings of a normative provision (‘norm formulation’), and interpretation in the strict sense, which selects one of these alternative meanings, uses the term ‘interpretative statement’ only in this latter sense (Aarnio, 1990, 182).

5 The distinction between signifier and signified as two dimensions of the sign goes back to the French linguist Saussure (1922, 97–100; cf. Barthes, 1964, 103–9; Eco, 1975, 25–6). This difference

Constitutionalism and the Paradox of Principles and Rules. Marcelo Neves, Oxford University Press. © Marcelo Neves 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192898746.003.0002

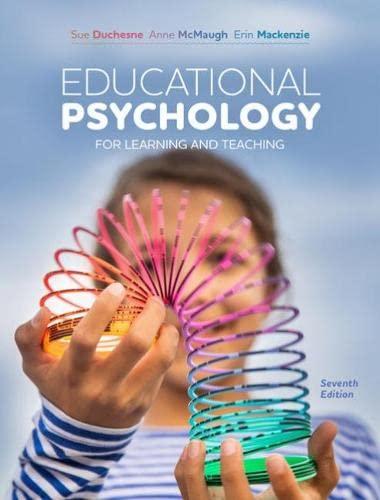

Norm provision

Norm statement Norm proposition Norm Level of signi er Level of signi ed sion tate No pr m

implies a semantic relationship of signification or, more broadly, of meaninggiving in the communication process. In the context of this work, however, this is not a relationship between two poles only (i.e. between the provision and the norm); in fact, it sets up at least a four-element circular process between a normative provision, norm, normative statement and a normative proposition (see Figure 1.1). Considering a normative provision, it is worth asking which norm(s) or normative meaning(s) may or ought to be attributed to it. The normative (or interpretive) statement assigns certain normative meaning(s) or norm(s) to the normative provision. However, again, one can ask which normative meaning(s) or norm(s) was (were) attributed to the provision by the normative (or interpretive) statement, that is, which normative (interpretive) proposition was expressed through this statement.6 This is not a linear relation, as with meta-language and object-language.7 Instead, it implies a reflexive circularity in the communication process of meaning-giving.

has been adopted, mutatis mutandis, by various theoretical models. See e.g. Lévi-Strauss, 1973 [1950], XLIX–L, referring to the discontinuity between signifier and signified, the overabundance of signifiers and the floating signifiers; Lacan, 1966, 372 and 501–2, pointing out the ‘discrepancy between signified and signifier’ and the closed character of the signifier’s order/chain, as well as its autonomy in relation to the signified.

6 Kelsen distinguishes between legal proposition and (prescriptive) legal norm, with the former being descriptive of the latter (Kelsen, 1960, 73–9). However, he defines the legal proposition (Rechtssatz) in particular or the ‘ought-proposition’ (Soll-Satz) in general as a descriptive statement (beschreibende Aussage) (cf. Kelsen, 1960, 73 and 81–3). In the present book, I correspondingly distinguish, at the level of the signifier, between normative statement (= statement of a normative proposition) and normative provision (or text of a norm). In the translation of Kelsen’s book originally published in English under the title General Theory of Law and State and of his masterwork Reine Rechtslehre [Pure Theory of Law], the term ‘Rechtssatz’ (legal proposition) was disastrously translated into the expression ‘rule of law’ (Kelsen, 1945, 45–7; 1960, 73–9 (Engl. trans., 1967, 71–5)).

7 In the sense of Russell’s hierarchical theory of types (Russell, 1994 [1908], 75–80; 1956 [1940], 62 ff.). See also Tarski, 1935; Carnap, 1948, 3–4; Barthes, 1964, 130–2. Criticizing this kind of distinction, Hofstadter (1979, 21 ff.) argues that the theory of types would ban ‘the strange loops’ and paradoxes within language, leading to a hierarchy between object language and meta–language. Although Hofstadter’s criticism of Russell’s theory of types is controversial in the realm of formal artificial language, such as mathematics and formal logic, his ideas on ‘strange loops’ and ‘tangled hierarchies’ makes sense when applied to ordinary language, even if it is a specialized language, such as law, humanities and social sciences. I will return to this issue later (see below p. 93).

Figure 1.1 Four-element circular process of norm construction.

Besides the signifier and the signified, the referents are relevant at the semantic level, which are not the ultimate raw material of the experience (whose existence is only assumed in the communicative process), but instead are facts and objects constructed in the language, or rather in the communication process. Thus, one is confronted, on the one hand, with the relationship between legal norm text (signifier) and legal norm (signified), and on the other hand, with the relationship between legal norm and legal fact (referent). In turn, the legal fact is defined mainly in terms of the norm scope, that is the abstract description of the fact(s) capable of bringing about the respective concrete legal consequence(s).8 It is further worth distinguishing the legal fact defined in terms of the norm scope from the fact situation or fact pattern [Sachverhalt]9 as the set of circumstances counted as relevant (and thus communicatively constructed) to the application of the norm, whose selective qualification according to the norm scope leads to the construction or definition of the legal fact, which is followed by the legal consequence. The fact pattern is not an underlying raw datum, the pure material of the experience, but something that has already entered the legal realm, that is it has already been processed by the legal language or communication.10

8 I employ here the phrase ‘legal facts’ in the sense of ‘juridical’ or ‘juristic facts’ (‘fait juridique’, ‘fatto giuridico’, ‘hecho juridico’, ‘facto jurídico’), according to its traditional use in continental jurisprudence, as it is accurately defined and exemplified by Hage (2005, 225): ‘Juristic facts are facts to which the law attaches consequences. Examples of juristic facts are sale, theft, death and lapse of time. Possible legal consequences of these examples include the coming into existence of the vendor’s right to be paid, the liability of the thief to be punished, inheritance and preclusion of criminal proceedings, respectively.’ In turn, I employ ‘norm scope’ to refer to the ‘norm condition(s)’ (‘protasis of a norm’, ‘Tatbestand’), i.e. the part of a norm that defines abstractly the ‘juristic fact’—a usage which also derives from this same tradition, in particular German legal culture. The other part, ‘norm conclusion’ (‘apodosis of a norm’, ‘Rechtsfolge’), establishes the abstract definition of the ‘legal consequence’ of a given norm (see e.g. Hage, 2005, 87–8, specifically about the rule condition and the rule conclusion as parts of a rule; Alexy, 1986, 83–4 (Engl. transl. 2002, 53–4; in this translation, ‘Tatbestand’ was usually translated as ‘scope of rights’; cf. ibid. 272 ff., Engl. trans. 196 ff.)).

9 I have to admit here that it is often difficult to translate expressions between different legal cultures, since there is often ambiguity between terms used within the same legal culture. Concerning the distinction between Tatbestand (here translated as ‘norm condition’) and Sachvehalt (here translated as ‘fact pattern’), the following passage of a German legal dictionary shows the ambiguity: ‘Sachverhalt is the specific factual event in the reality of life. The legally relevant Sachverhalt is the object of the legal application. In the legal application, the (concrete) effects brought about by Sachverhalt are checked on the basis of the respective abstract legal norms. In the procedural law, Sachverhalt is often referred to as Tatbestand (e.g. § 313 I No. 5 ZPO [German Code of Civil Procedure]), although the legal methodology understands the latter as the sum of the abstract conditions for an abstract legal effect’ (Köbler, 2003, 403). Elsewhere in the same dictionary (ibid. 456), it is stated that in the procedural law (quoting the above-mentioned provision of the ZPO), Tatbestand is the ‘concise description’ of a Sachverhalt, but here it refers to the concrete situation.

10 Pontes de Miranda, 1974, vol. I, 21; 1974, vol. V, 231. Against the naturalistic perspective of Pontes de Miranda, I understand the fact situation or fact pattern as a legal construct, placing it at the level of the referents of the legal language or communication, but distinguishing it from the legal fact, which is also located at the level of the referents, but additionally has legally binding effects.