https://ebookmass.com/product/conservation-technology-sergea-wich/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Conservation Drones Mapping and Monitoring Biodiversity Serge A. Wich

https://ebookmass.com/product/conservation-drones-mapping-andmonitoring-biodiversity-serge-a-wich/

ebookmass.com

Portfolio Diversification Francois-Serge Lhabitant

https://ebookmass.com/product/portfolio-diversification-francoisserge-lhabitant/

ebookmass.com

Biodiversity Conservation: a Very Short Introduction David W. Macdonald

https://ebookmass.com/product/biodiversity-conservation-a-very-shortintroduction-david-w-macdonald/

ebookmass.com

Sight Unseen: The Greek Gift Book One Juniper Rose

https://ebookmass.com/product/sight-unseen-the-greek-gift-book-onejuniper-rose/

ebookmass.com

Engineering

https://ebookmass.com/product/engineering-legitimacy-1st-ed-editioniva-petkova/

ebookmass.com

Health Promotion in Multicultural Populations: A Handbook for Practitioners

https://ebookmass.com/product/health-promotion-in-multiculturalpopulations-a-handbook-for-practitioners/

ebookmass.com

The Nightmare Thief Series, Book 1 Nicole Lesperance

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-nightmare-thief-seriesbook-1-nicole-lesperance/

ebookmass.com

Ryan's Retina 7th Edition Srinivas R. Sadda Md (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/ryans-retina-7th-edition-srinivas-rsadda-md-editor/

ebookmass.com

Addiction & Recovery For Dummies 2nd Edition Paul Ritvo

https://ebookmass.com/product/addiction-recovery-for-dummies-2ndedition-paul-ritvo/

ebookmass.com

Data

https://ebookmass.com/product/data-science-for-genomics-1st-editionamit-kumar-tyagi/

ebookmass.com

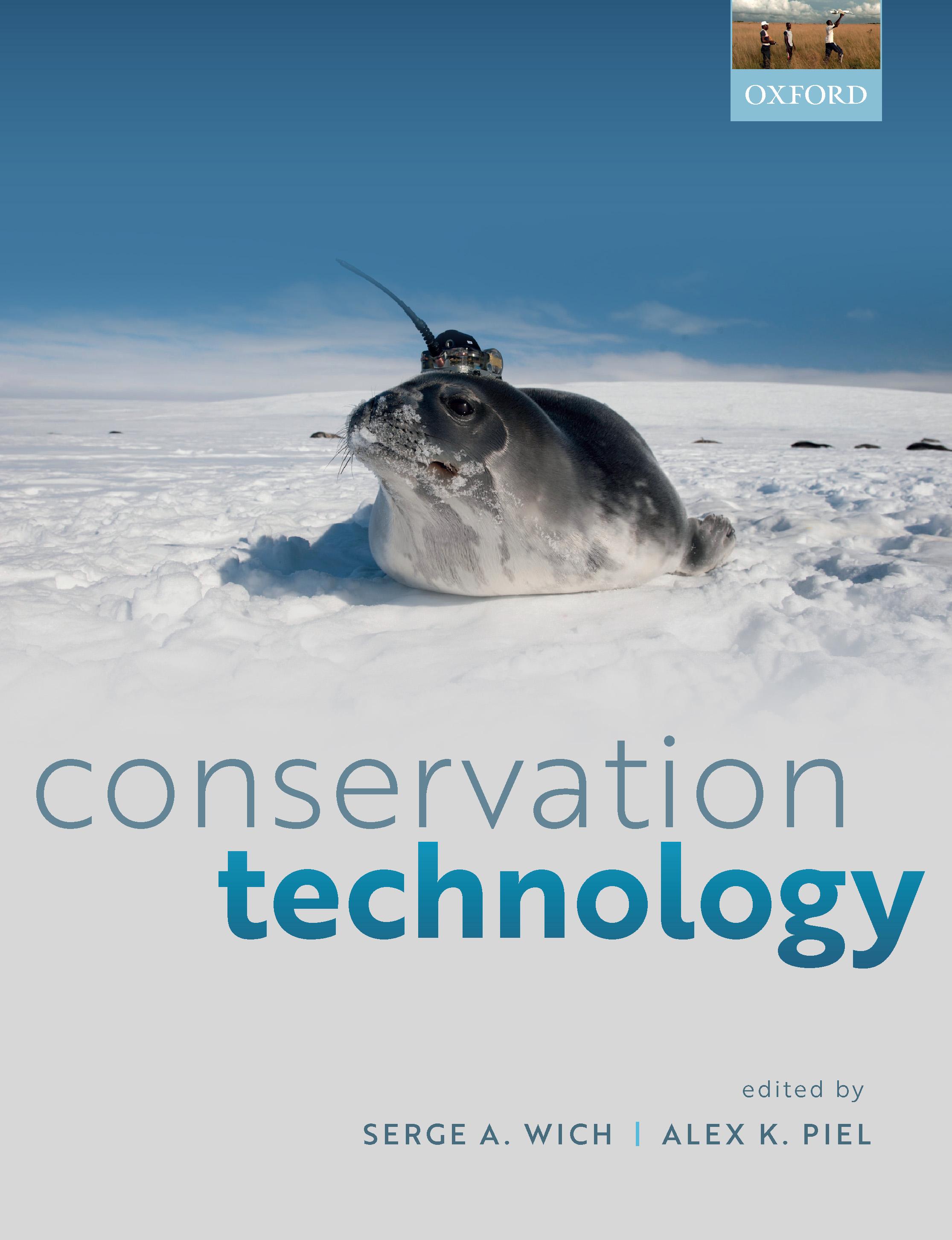

ConservationTechnology

Conservation Technology

EDITEDBY

SergeA.Wich

SchoolofBiologicalandEnvironmentalSciences, LiverpoolJohnMooresUniversity,UK

AlexK.Piel

DepartmentofAnthropology, UniversityCollegeLondon,UK

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries ©OxfordUniversityPress2021

Themoralrightsoftheauthor[s]havebeenasserted

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,stored inaretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData

Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2021936415

ISBN978–0–19–885024–3(hbk.)

ISBN978–0–19–885025–0(pbk.)

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198850243.001.0001

Printedandboundby

CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

Linkstothird-partywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythird-partywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Preface

TheideaforthisbookdevelopedduringanMSc fieldcoursethatweteachinTanzania,whereAlex directsalong-termprimatefieldsiteintheIssa valley.FornearlyadecadeatIssa,wehaveused varioustechnologiestoestablishandincreasechimpanzee(andotherwildlife)detectionsandmonitoring.AlexstartedtheremanyyearsagoforPhDwork bydeployingacustom-designedandbuiltpassive acousticmonitoring(PAM)system,integratedwith radiostoconductreal-timemonitoringofchimpanzeepanthoots,inanefforttolocalizecallersto improvehabituationefforts.Lateron,weinitiateda collaborationontheusageofdronesinwesternTanzaniatodetectchimpanzeenests.Wefirsttrained togetherintheNetherlands,beforeAlexandFiona Stewartflewtheirfirstmissionsusingfixed-wings onaregion-widechimpanzeesurvey.Whileinitial flightswereliterallybumpy,nowdronesarearegularpartofvariousconservationquestionsbeing askednotjustinTanzania,butalsoacrossgreatape distribution.

IssanowintegratesandreliesonPAM,camera traps,drones,digitaldatacollectionontablets,DNA collectionthroughprimatefaeces,andusesmachine learningtoanalyseimagesfromcameratrapsand

drones.Thefieldsiteisnotuniqueinitsuseoftechnology,andhencewefeltthatstudents,colleagues, andcollaboratorsatothersitesaroundtheworld wouldfindabookthatdescribestheseandother conservationtechnologiesuseful.Werealizedthat eventhoughtherearealreadybooksthatdescribe specifictechnologiessuchascameratraps,machine learning,ordrones,noonevolumecoversawide arrayoffield-friendlytechnologies.Wehopethat thebookisnotonlyapplicableforstudents,butalso formanagersofconservationareaswhomoreoften thannothavetomonitoralargenumberofanimalspeciesandvegetationwithlimitedresources andwhereresultsaredirectlyfedintopoliciesand practices.Determiningwhatoptionsthereareavailabletodosoandwhateachoftheseoptionsentails intermsofdatacollected,analyses,costs,durability,andspecificscientificquestionsthatcanbe answeredwiththedataisnoteasy.Wehopethat thisvolumehelpsthosemanagersandconservation practitionerstomakesuchchoices.Similarly,we feelthatthisbookwillbeofuseforcolleagueswho aredevelopingorinitiatingnewresearchprojects andseekanoverviewoftechnologiesthatarecommonlybeingusedinconservation.

Acknowledgements

WewouldliketothankLiverpoolJohnMoores Universityforthesupportofthedronelabthat hasbeeninstrumentalforourdronework,trainingthenextgenerationofconservationists,and foritssupportinusinganddevelopingtechnologyforconservationingeneral.Wewouldalso liketothanktheUCSD/SalkCenterforAcademic ResearchandTraininginAnthropogeny(CARTA), whichhassupportedprimateresearchandconservationeffortsintheIssavalley.

WewouldliketothankLianPinKoh,Peter Wrege,AmmieKalan,JorgeAhumada,Oliver Wearn,LochranTraill,ErinVogel,RichBergl,DanijelaPuric-Mladenovic,StefanoMariani,ChrisGordon,JanvanGemert,JoshVeitch-Michaelis,Liana Chua,andKoenArtsforkindlyreviewingthe chapters.

WewanttothanktheOxfordUniversityPress teamforofferingusthechancetoworkwiththem onthisbook,especiallyIanShermanandCharles Bathwhoprovidedexcellentguidancethroughout theprocess.

SergeisthankfulforthesupportfromTine,Amara,andLennduringthewritingofthisbookand acceptingmyabsenceduringthemanyfieldtrips overthepastyearstoworkwithsomeofthetechnologiesfeaturedinthisbook.Ihopeitwillcontributetomoreandbetterconservationofwildlife andtheirhabitats.

Alexisgratefulforthepatienceandsupport offeredbyFionaStewartandhisfavouriteprimates FinlayandCaelan.Maythesetechnologiesallow forthecontinuedconservationofwildlifeforyour childrentoobserveandappreciateaswell.

3.3Widerapplications:areviewofwhathasbeendone

3.3.1Land-coverclassificationandland-coverchangedetection

3.6Socialimpact/privacy

4.1.1Whatquestionsareweasking?

4.1.2Traditionalmethodsandhowtechnologiesovercome limitations

4.2PAM:fromdatacollectiontodataanalyses

4.2.1Datacollection

4.2.2Analysis

4.3Casestudy:detectingwildchimpanzeesusingPAM

5Cameratrappingforconservation

FrancescoRoveroandRolandKays

5.1Introduction

5.1.1Whatquestionsarebeingasked?

5.1.2Traditionalmethodsandlimitations

5.1.3Howtechnologyaddressesthis

5.2NewTechnology:hardware,software,anddataanalysis

5.3Reviewofcameratrappingconservationapplications

5.3.1Whatcamerasaregoodatdocumenting

5.3.2Cameratrapsforconservation—spatialandtemporal comparisons

5.4Casestudies

5.4.1Integratemonitoringwithmanagement

5.4.2Designfit-for-purposemonitoringprogrammes

5.4.3Engagepeopleandorganizations 93

5.4.4Ensuregooddatamanagement 93

5.4.5Communicatethevalueofmonitoring 94

5.5Limitations/constraintsofcameratrapping

5.6Socialimpact/privacy

5.7Futuredirections

6Animal-bornetechnologiesinwildliferesearchandconservation

KasimRafiq,BenjaminJ.Pitcher,KateCornelsen,K.WhitneyHansen,AndrewJ.King, RobG.Appleby,BrianaAbrahms,andNeilR.Jordan

6.1Introduction

6.2Newtechnology

6.2.1Animal-bornetrackingtechnologies

6.2.2Non-trackinganimal-bornetechnologies

6.2.3Dataanalyses:softwareinuse

6.3Casestudy:usingtrackingtechnologiestoidentifykeyhabitats forconservation

6.3.2Results/discussion

6.4Limitationsandconstraints

6.4.1Samplesizes

6.4.2Deviceweightlimitationsandanimalwelfare

6.4.3Balancingdataresolutionwithstudylength

6.4.4Analysingtrackingdata

6.5Socialimpact/privacy

6.6Futuredirections

6.6.1Open-sourcehardware

6.6.2Opendatainanimaltracking

6.6.3Machinelearningontheedge

CherylD.Knott,AmyM.Scott,CaitlinA.O’Connell,TriWahyuSusanto, andErinE.Kane

7.1Introduction

7.1.1Whatquestionscanbeaskedusingfieldlaboratorymethods?

7.1.2Traditionalmethodsandlimitations

7.2Developmentofnewtechnologyforsamplepreservationand analysis

7.2.1Nutritionalanalyses

7.2.2Hormonalanalyses

7.2.3Urineandfaecalhealthmeasures

7.2.4Fieldmicroscopyforparasites

7.3Applicationstoconservation

7.3.1Nutritionalanalysis

7.3.2Energeticandsocialstress

7.3.3Reproductivehormones

7.3.4Healthandimmunefunction

7.3.5Parasiteprevalenceandspeciesrichness

7.3.6Geneticapplicationstoconservation

7.4CasestudyoforangutansinGunungPalungNationalPark, Indonesia

7.4.1Conservationandhealththreatsfacedbywildorangutans

7.4.2GunungPalungstudypopulation

7.4.3Compositionandhabitatdistributionoforangutanfoods

7.4.4Healthassessmentsfromurineandfaeces

7.4.5Genetics

7.5Limitationandconstraintsofnewtechnology

7.5.1Samplecollectionandhandling

7.5.2Fieldlabsetup

7.5.3Useofchemicalsanddisposalofbiologicalsamplesand contaminatedsupplies

7.5.4Long-termpartnerships

7.6Socialimpactandbenefitsoffieldlabs

7.7Futuredirections

8EnvironmentalDNAforconservation

AntoinetteJ.Piaggio 8.1Introduction

8.2.1Datacollection—studydesign

8.2.2Datacollection—targetingsinglespecies

8.2.3Datacollection—targetingmultiplespecies

8.2.4Datacollection—DNAcapture

8.2.5Datacollection-DNAisolation,purification,andamplification 163

8.2.6Dataanalyses

8.3Widerapplication—reviewofwhathasbeendone

8.4Casestudy

8.5Limitations/constraints

8.6Socialimpact/privacy

8.7Futuredirections

9Mobiledatacollectionapps

EdwardMcLesterandAlexK.Piel

9.1Introduction

9.2Newtechnology

9.2.1Datacollectionhardware

9.2.2Datacollectionsoftware

9.3Applications

9.3.1Behaviouraldatacollection 189

9.3.2Citizenscienceandcommunityengagement 189

9.3.3Mobilegeographicinformationsystems(GIS)and participatorymapping 190

9.3.4Mobiledevicesasmultipurposetools

DrewT.Cronin,AnthonyDancer,BarneyLong,AntonyJ.Lynam,JeffMuntifering, JonathanPalmer,andRichardA.Bergl

11.4Generalizableclassificationanddetectionforlow-qualityimages

11.4.1Problemoverview

11.4.2WhyCVforlow-qualityimagesmattersforconservation

11.4.3WhyCVforlow-qualityimagesischallenging

11.4.4ProgressinCVforlow-qualityimages

11.5Superviseddetectionandclassificationinimbalancedscenarios

11.5.1Problemoverview

11.5.2WhyCVwithimbalancedtrainingdatamattersfor conservation

11.5.3WhyCVwithimbalancedtrainingdataishard

11.6Emergingtopics

11.6.1Partialmodelreuse

11.6.2Human-in-the-loopannotation

11.6.3Simulationfortrainingdataaugmentation

11.7Practicallessonslearnedandchallengestothecommunity

11.8Otherreviews

12Digitalsurveillancetechnologiesinconservationandtheirsocial

TrishantSimlaiandChrisSandbrook

12.4Thesocialandpoliticalimplicationsofcameratrapsanddrones

12.4.1Infringementofprivacyandconsent

12.4.2Psychologicalwell-beingandfear

12.4.3Widerissuesinconservationpractice

12.4.4Datasecurity

12.5Counter-mappingandsocialjustice

13Thefutureoftechnologyinconservation

MargaritaMulero-Pázmány

13.1Currentscopeofconservationtechnology

13.1.1Researchquestionsandconservationapplications

13.1.2Resolution

13.1.3Animalwelfareandenvironmentalimpact

13.2Currentlimitationsandexpectedimprovementsinconservation technology

13.2.1Powersupplyanddatastorage

13.2.2Imagequality

13.2.3Connectivity

13.2.4Sensorstandardizationandintegration

13.2.5Regulations

ListofContributors

BrianaAbrahms CenterforEcosystem Sentinels,DepartmentofBiology,University ofWashington,Seattle.WA,USA

HerizoAndrianandrasana DurrellWildlifeConservationTrustMadagascarProgrammeand MinistryoftheEnvironmentandSustainable Development,Antananarivo,Madagascar

Rob.G.Appleby TheCentreforPlanetaryHealth andFoodSecurity,GriffithUniversityandWild SpyPtyLtd,Brisbane,Australia

RichardA.Bergl Conservation,Education,and ScienceDepartment,NorthCarolinaZoo, Asheboro,NC,USA

KateCornelsen CentreforEcosystemScience, SchoolofBiological,EarthandEnvironmentalSciences,UniversityofNewSouthWales, Sydney,Australia

DrewT.Cronin Conservation,Education,and ScienceDepartment,NorthCarolinaZoo, Asheboro,NC,USA

Anne-SophieCrunchant SchoolofBiologicaland EnvironmentalSciences,LiverpoolJohnMoores University,UKandGreaterMahaleEcosystem ResearchandConservationProject(GMERC), Tanzania

AnthonyDancer ZoologicalSocietyofLondon, London,UK

ChanakyaDevNakka IBMiX,Bangalore,India

K.WhitneyHansen EnvironmentalStudies Department,UniversityofCalifornia,Santa Cruz,CA,USA

MikeHudson DurrellWildlifeConservationTrust, Jersey,ChannelIslandsandInstituteofZoology, ZoologicalSocietyofLondon,London,UK

JasonT.Isaacs CaliforniaStateUniversity, ChannelIslands,CA,USA

SamualM.Jantz DepartmentofGeographicalSciences,UniversityofMaryland,MD, USA

LucasJoppa MicrosoftAIforEarth,WA,USA

NeilR.Jordan TarongaConservationSociety Australia,Sydney,CentreforEcosystemScience, SchoolofBiological,EarthandEnvironmentalSciences,UniversityofNewSouthWales, AustraliaandBotswanaPredatorConservation, Maun,Botswana

RolandKays DepartmentofForestryandEnvironmentalBiology,NorthCarolinaStateUniversity, Raleigh,USAandNorthCarolinaMuseumof NaturalSciences,NC,USA

ErinE.Kane DepartmentofAnthropology,Boston University,Boston,MA,USA

AndrewJ.King DepartmentofBiosciences, SwanseaUniversity,Swansea,UK

CherylD.Knott DepartmentofAnthropology andDepartmentofBiology,BostonUniversity, USA

BarneyLong Re:Wild,Austin,TX,USA

StevenN.Longmore AstrophysicsResearch Institute,LiverpoolJohnMooresUniversity, Liverpool,UK

AntonyJ.Lynam CenterforGlobalConservation, WildlifeConservationSociety,NewYork,NY, USA

EdwardMcLester SchoolofBiologicalandEnvironmentalSciences,LiverpoolJohnMoores University,Liverpool,UK

DanMorris MicrosoftAIforEarth,WA,USA

MargaritaMulero-Pázmány SchoolofBiological andEnvironmentalSciences,LiverpoolJohn MooresUniversity,Liverpool,UK

JeffMuntifering SavetheRhinoTrust,Namibia

CaitlinA.O’Connell DepartmentofBiological Sciences,HumanandEvolutionaryBiology Section,UniversityofSouthernCalifornia, LosAngeles,CA,USA

JonathanPalmer CenterforGlobalConservation, WildlifeConservationSociety,NewYork,NY, USA

AntoinetteJ.Piaggio UnitedStatesDepartment ofAgriculture,AnimalPlantHealthInspectionService,WildlifeServices,NationalWildlife ResearchCenter,FortCollins,CO,USA

AlexK.Piel DepartmentofAnthropology,UniversityCollegeLondon,London,UKandGreater MahaleEcosystemResearchandConservation Project(GMERC),Tanzania

LilianPintea JaneGoodallInstitute,USA

BenjaminJ.Pitcher TarongaConservationSociety AustraliaandDepartmentofBiologicalSciences, MacquarieUniversity,Sydney,Australia

KasimRafiq EnvironmentalStudiesDepartment, UniversityofCalifornia,SantaCruz,USAand CenterforEcosystemSentinels,Department ofBiology,UniversityofWashington,Seattle. WA,USAandBotswanaPredatorConservation, Maun,Botswana

FrancescoRovero DepartmentofBiology, UniversityofFlorence,Florence,Italyand MUSE—MuseodelleScienze,Trento,Italy

ChrisSandbrook DepartmentofGeography, UniversityofCambridge,Cambridge,UK

AmyM.Scott DepartmentofAnthropology, BostonUniversity,Boston,MA,USA

TrishantSimlai DepartmentofGeography, UniversityofCambridge,Cambridge,UK

TriWahyuSusanto DepartmentofBiology, NationalUniversity,Indonesia

SergeA.Wich SchoolofBiologicaland EnvironmentalSciences,LiverpoolJohn MooresUniversity,UKandInstitutefor BiodiversityandEcosystemDynamics, UniversityofAmsterdam,Amsterdam, theNetherlands

Conservationandtechnology: anintroduction

AlexK.PielandSergeA.Wich

Thoseofuswhostudywildlifeandsimultaneously thethreatstoitfindourselvesattheintersection oftwounprecedentedages:theInformationor DigitalAge—whereelectronicdevicesanddigital datagoverntheflowofinformation—andthe Anthropocene—wherehumanactivitiesalterthe dynamicstolife,includingclimate,ocean,and forests(Steffenetal.,2007; Joppa,2015).Thatthe naturalenvironmentisbeingalteredbyanthropogenismisundisputed;thattechnologicalinnovationscanassistconservationbiologiststosupport solutionstotheseglobalproblems,however,isnot. Thesubjectofthisbookiswhattechnologiesare beingusedinconservationpractice,toaddresswhat typesofquestionsandwhataretheassociatedchallengestotheirdeployment.

Applicabletechnologymustaddressfundamentalproblemsinthefield.Assuch,theprocessbegins withasimplesetofkeyquestions:Whatdoconservationbiologistsneedtoknowtosupportconservationmanagementandpolicy?Whichdata, resolution,orparametersarenotbeingcaptured thatneedtobe?Whatexistingtechnologycanhelp obtainthetypeandqualityofdataneeded?How doweenhancedatacapture?Fromamanagement perspective,canweidentifynotjusthotspotsofbiologicalinterest,butparticularkeyresources(specifictrees,watersources)ratherthanbroaderareasor generalvegetationtypes(Allanetal.,2018)?Finally, iftechnologyoffersprogresstowardstheseanswers, thereisasubsequentsetofimportantquestionsto

consider,namelytheefficacyandefficiencyofany new,innovativemethodand,relatedly,theethical andpracticalimplicationsofusingnewdevices (Ellwoodetal.,2007).

Conservationistsrequireasuiteofdatato addresskeyquestionsonanimalpresence,distribution,habitatintegrity,andthethreatstospecies andentireecosystems.Broadly,conservationists usethesedatatoassessbiodiversity,monitor ecosystems,investigatepopulationdynamics,and studybehaviour,allinresponsetoanincreasinglylargeandglobalanthropogenicfootprint.We oftenwanttodothislongitudinally,especiallyto examinetrendsandchangeovertime,andalso geographically,acrossincreasinglyvastlandscapes. Moreover,long-termprojectsarefacedwithhowto digitizeandstandardizedatacollectionprotocols whilemaintaininginterobserverreliability,allthe whileconfrontedwithrotatingstaffandoftenthe trainingofvolunteers/interns/students.Alas,conservationscienceinvolvesnotonlyknowingwhat dataareneeded,butwhattoolscanhelpacquire themandfurther,howtostore,process,andanalysethemonceprocured.Thefinal,andperhaps mostcrucialstepisprovidingresultsinawaythat facilitatesactionsbydecision-makers(Chapter 2).

Specifically,conservationscientistsneeddataon speciesdiversity,countsofindividualanimals, migrationpatterns,habitatintegrity,resourceavailabilityanddistribution,andinformationonanimalhealth,forexample.Thesedatainformon

landscape-widequestionsaboutanimalabundance anddistribution,aswellasdiseaserisks.Higherresolutiondataongroup-andevenindividuallevelbehaviourareimportant.Diseaseinfluences demography(birthanddeathrate),groupcomposition,andindividualbehaviour(Prenticeetal., 2014).Withwildlifediseaseandzoonosesespeciallyawidespreadconcernforconservationists(Deem etal.,2008),identifyingpathogensandconducting diagnosticsforevaluatinganimalhealtharecritical.Historically,theseprocesses(1)requiredcollectionandsubsequentexportofanimaltissueor by-products(e.g.faeces),(2)werecostlyinterms ofmoneyandtime,and(3)oftenresultedindamagedshipmentsandcontaminatedorruinedsamples.Thereisthusgreatdemandformobilelabsto processsamplesinthefield.

Together,dataonwildlifepresence,habitat, behaviour,health,andthreatsprovidesnapshots ofspeciesorhabitatconservationstatus,whichare usefulforestablishingabaselineunderstanding andthesubsequentneedformanagement.Ultimately,though,effectivebiodiversityconservation requiresfastandeffectivemeansofassessinghow speciesdiversityornumbersshiftinresponseto anthropogenicchangeslikesettlementexpansion, conversionofforesttoagriculture,andpoachingamongmanyothers.Traditionally,datafrom cameratrapsanddroneswerecollectedinisolation;contemporaryintegrationoftechnologyallows thesimultaneousprocessingofmultipletypesof data,withnetworksofvarioussensorscollectingdataacrossplatforms(Turner,2014).Scientists canthencombinedatacollectedfrommorerecent technologieslikebiologgerswithmoretraditionalecologicaldata,(e.g.temperature,rainfall)to analyserelationships—ofteninnearreal-time—to betterunderstandthebehaviouralconsequencesof achangingworld(Wall,2014; Kaysetal.,2015). Knowingthetypeandseverityofthreatshasimplicationsfortheurgencyneededtoaddressthem aswell.Thevariabilityofanimalresponsesfurtherinfluencesmanagementstrategies.Whatanimalseat,wheretheygo,andhowtheybehave morebroadly(e.g.activitybudgets,groupingpatterns)inresponsetoreducedhabitatavailability, humanpresence,orintroducedspecieshasbearingonwhatstepscanbetakentoabateimminent threats.

Giventheimportanceofecologicalmonitoringfornearlyanyconservationproject,conservationscientistshavelongbeeninterestedinanimal presence,distribution,anddensity.Traditionally, censusandmonitoringmeasureswereconducted viacapture-recaptureapproachesorconventional ground(e.g.reconnaissance)surveys,bothofwhich arealmostentirelydependentonstafforstudentavailabilityandcapacity,withhandwritten documentationtraditionallystoredindatabooks (Vermaetal.,2016).Inalmostallcases,datacollectorswererequiredtobeintheareaswhere wildlifelives,raisingquestionsaboutdisturbance andgenerallytheroleoftheobserverininfluencinganimalbehaviourandmovement(Kucera& Barrett,2011; Nowaketal.,2014).Moreover,the largerthedatacollectionteam,thegreatertheconcernforinterobserverreliability,whetherbecause ofvariabilityinresearcherknowledge,experience, bias,ortraining.Meanwhile,especiallyforlongtermprojectswithpermanentresearcherpresence onsite,databookspileduponbookshelveswith armiesofundergraduatestudentsorinternsrecruitedtodigitizethemforsubsequentanalyses.

Oneofthemostcommonlyusedmethodsfor datacollection,bothtraditionallyandthroughthe presentforcensusingvarioustaxa,isvialinetransects(Yapp,1956).Inthismethod,researcherswalk astraightline,oftenofrandombearing,andrecord theperpendiculardistanceofalldirectorindirect wildlifeobservedfromtheline.Thoroughdescriptionsoflinetransectusecanbefoundinvariousreviews(Chapter 5; Krebs,1999; Buckland etal.,2001; Thomasetal.,2010).Thismethodof samplingcanbepractical,effective,andinexpensive.Bycalculatingthedistancewalkedandthe widthoftheareavisibletoobservers,researchers canestimatepopulationdensitiesofspeciesof interest.Linetransectshavebeengloballyapplied tovarioustaxa,predominantlyusedwithterrestrial(Varman&Sukumar,1995; Plumptre,2000) andmarine(deBoer,2010)mammals,andprimatesspecifically(Brugiere&Fleury,2000; Bucklandetal.,2010).Initiallyusedforgroundsurveys,thismethodisnowcommonforestimatingthepopulationsizesoflargemammals(e.g. Africanherbivores—Jachmann,2002),wherevast areasneedtobecoveredtosufficientlysurveydistribution(Trenkeletal.,1997).Aeriallinetransects

havealsobeenusedforbirds(Ridgway,2010)and marinespeciesaswell(Milleretal.,1998).

Whenestimatingpopulationdensitiesdirectly isnotpossible,scientistshavehistoricallyused methodsthatrevealrelativemeasures.Thisisparticularlyusefulwithbirds,forexample,wherethe numberofcallsperunitareaprovidesarelative measureofpopulationdensity.Alsoknownaspoint counts,thesameapproachissometimesusedfor roadsidetalliesofwildlifeaswell(reviewedin Schwarz&Seber,1999).Thesetypesofsurveys arebasedontheproportionofobservedevidence tosearcheffortandtheassumptionthatchange overtimeisattributabletopopulationincreaseor decrease.Despitetheirpervasiveuse,pointcounts arenotsuitableforassessingrelativeabundanceof rareorcrypticspecies(Ralphetal.,1995)giventhe typicallylowsamplesize.

Animalpresenceanddistributionaregenerallydependentonhabitatquality,whichisanother importantmetricforconservationscientists.Not onlyisthereagrowingempiricalevidencethat habitatqualityinfluencesoccupancyofvarious taxa,fromplants(Honnayetal.,1999)toprimates (Arroyo-Rodríguez&Mandujano,2009; Marshall, 2009; Foersteretal.,2016),butalsoqualitycaninfluencespeciesspatialdynamics,especiallyinfragmentedlandscapes(Thomasetal.,2001;reviewed in Mortellitietal.,2010).Evaluatinghabitatquality isespeciallyusefulwhenidentifyingtheecologicalconstraintsthatinfluencefitnessisimpossible (Johnson,2005).

Theearliestwaystomeasurehabitatwerevia groundsurveys,withanattempttoidentifythose featuresthatfacilitateorpreventanimalpresence (Forbeyetal.,2017).Methodsincludedcounting ortrappinganimals,collectingfaeces,andgenerallymappingkeylandmarks.Thesecanincludethe countingofimportantresources,suchasfoodand watersources,nestorsleepingsites,naturalbarriers(e.g.rivers),andanthropogenicfootprintslike agricultureandsettlements.Theycanalsoinclude measurementsofhabitatintegritythatfurther affectanimalmovement,suchasfragmentation, canopycover,andspeciesdiversity(Johnson,2005). Historicallythesedatahavebeencollectedfrom ground-truthing,includingspecimencollectionfor diversityindices,manualtreemeasurementsfor gaugingcanopyheight,andmappinglandmarks

fromrecces.Likemostofthesetraditionalmethods, newtechnologyhasenhancedthescopeandquality ofdatathatcanbecollectedandthusimproved dramaticallyhowweunderstandwildlifehabitat quality(Forbeyetal.,2017).

Analysisoflandcoverfrommannedaircraftwas initiallyacommonmethodtoassesslandscapewidepatternsofhabitatqualityandhabitatchange. Fromthe1970s,satelliteimagerybecamethepreferredmeansofgeneratingthesedata(Royetal., 1992; Serneelsetal.,2001)andremotesensingwas identifiedasareliablemethodforpredictingfinescalehabitatqualityandusebyindividualspecies (e.g.sagegrouse—Homeretal.,1993).Remotesensinghasbeenusedtoinformonvegetationtypes andproportions(Curran,1980),especiallyuseful forspecialistspeciesorelseincaseswherehumans targetspecifictreespeciesforextraction(Kuemmerleetal.,2009; Brandtetal.,2012).

Eventually,how,when,andwhereanimalsnavigatethesehabitatswhenobserversarenotaround emergedascentralquestionsinconservationscience.Examplesincludehowextensivecropraiding isbycrypticspecies(e.g.slothbears—Joshietal., 1995)andevaluationsoftranslocated(orreintroduced)species(e.g.dormouse—Bright&Morris, 1994).Locatingandtrackingindividualanimals usingglobalnavigationsatellitesystems(GNSS) reliedoncumbersome,expensive,andheavyradio collars(Rasiulisetal.,2014).Earlyversionsof GNSScollarsstoreddatain-houseandreliedon collarremovaltoretrievedata.Moreover,especiallyforlargeranimals,pioneeringstudieshad negativeresultsforconservation.Alibhaiandcolleagues(Alibhaietal.,2001; Alibhai&Jewell,2001) describedadirectrelationshipbetweenimmobilizationschedule(thenumberofdartingepisodes)and reducedinter-calfintervalinblackrhinos,raising scientificandethicalissuesintheearlytestsofthis technique.Subsequentdeploymentswereplagued withsysteminaccuracies,humanandtransmission error(sometimesupto1000m—Habibetal.,2014), anddisturbancetothecollaredindividual.Besides radiocollars,‘geolocators’,whichwereattached toanimals,usedthetimeofdaytocalculatean animal’sposition,andsowerepronetolargeerror marginsasmuchastensofkilometresfromthe animal’sactuallocation(Weimerskirch&Wilson, 2000).Otherproblemsabounded.

Traditionalsystemshavefacedchallengeson numerousdimensions,fromlimitedspatialand temporalcoveragetoissuesconcerningdatarecording,storage,transmission,andinterobserverreliability(Vermaetal.,2016).Technologyisaddressing thoselimitations,sometimesmultipleatatime.A lookatthenumberofpeer-reviewedworksonthe topicofconservationtechnologyshowsacleartrend overthelastfewdecadesthatusestheterm,‘ConservationTechnology’(Figure 1.1).

Recentdevelopmentsinconservationtechnologyimprovethespeedandtypeofdatacapture, includingthequality,quantity,andreliabilityof thisprocess,aswellasthewaysandspeedthat dataareanalysed.Forthestudyoflarge,especiallyterrestrialspecies,groundteamshavelong beenlimitedbythetimerequiredtocovervast areasaswellasthedangerandlogisticalchallengesofsurveyinginremoteareas.Groundsurveyscontinuetobeusedandoffertheadvantage ofidentifyingsmall-scalethreats(e.g.individual snares)thatothermethodswillmiss,butincreasingly,groundteamsarenowcomplemented,if notreplacedentirely,withremotesensingmethods.Thecurrentvolumedetailsthesemethods,as wellastheimplicationsfortheiruse.Today,capturingdataaboutspeciespresence/absenceand habitatchangeacrosslargespatialscalesiscurrentlyconductedusingeithermedium/high-resolution satelliteimagery(Chapter 2)ordrones(Chapter 3). Astheapplicationsandusesofthesemethodsare

driven,andlimited,bythesensorstheirvehicles carry,wediscussthembothhere.More,regardlessofoperator,theultimateobjectiveofimaging issimilaracrossplatforms,forexample,toprovide spatiallyspecificanalysisandspatiallydistributed dataontargetsthatexhibitrecognizablesignatures. Themostcommontypeofremotesensingfrom eithersatellitesordronesismultispectral,whereby sensorsassesstheradiation(orbrightness)emitted fromsurfaceareasonearth.Thecostofhighresolution(sub-metre)imageryandsensorscontinue todeclineasthediversityofapplicationsexpands inconservation.Forexample,LiDAR(lightdetectionandranging)onlowflyingaircraft,butalso fromspace-bornesatellitesanddrones,estimates above-groundcarbonstocksandoverallbiomass, ecosystemstructure,andbroadlyprovidescritical dataforenvironmentalmanagement(Urbazaevet al.,2018; VaglioLaurinetal.,2020).Advancesin hyperspectralremotesensing—multispectralsensorswithhundredsofbandsacrossanearcontinuousrange,includingvisible,infrared,ad electromagneticspectrum—havefurtherpotential, beingabletoidentifyfine-scalefeatureslikehabitatvariationatthelevelofsubtlevegetativeor soildifferences(Turneretal.,2003; Shiveetal., 2010).Satelliteswithhyperspectralsensorsoffer theabilitytoremotelymapspecificplantspecies andthusecosystemresiliencetoanthropogenism (Underwoodetal.,2003; Lietal.,2014).Finally, increasingly,andespeciallywithdrones,usersare

Figure1.1 Thenumberofscientific publicationsonconservationand technologypublishedbetween1975and 2019.Resultsreflectasearchfortitle words‘Conservation’and‘Technology’in Scopus(http://www.scopus.com).Thedata searchwasconductedon27April2020.

alsoapplyingthermal-sensitivesensors—detecting temperaturedifferentials—whichidentifyanything fromfirestopeopleandanimalsacrosslargelandscapes(Chapter 3).Forconservationists,thermal imagingsensorsareprovidingdatatoanswerquestionsaboutspeciesdistribution,counts,andthe locationoffires(Chapter 3).

Satellitesanddronesofferviewsfromaboveand thussufferfromaninabilitytoaccessground-based biodiversityifthosearecoveredbyvegetationor aretoosmall.Twoofthemostcommonmethodstocaptureground-truthingdataarecamera traps(Chapter 4)andacousticsensors(Chapter 5). Bothhavebeenusedfornearlyacenturyinconservationstudies.Evenmoresothansatelliteor droneimagery,camerasandacousticsensorscaptureespeciallyspeciescompositionanddiversity acrossasampledarea.Historically,datacaptured fromthesedeviceswereusedpredominantlyto buildspecieslists.However,analyticalandtechnologicaldevelopmentsinbothhavetransformed theirapplicabilitytoconservation-relevantquestions.Forexample,withbothmethodsresearchers cannowcalculateanimaldensityfromeitherDISTANCEsampling(acoustics: Marquesetal.,2013, cameratrapping: Cappelleetal.,2019)orfromspatiallyexplicitcapture–recaptureanalyses(acoustics: Efford&Fewster,2013;cameratrapping: DesprésEinspenneretal.,2017).Additionally,thehardwareofbothcamerasandacousticsensorshas alsoimproved.Commercialcameraswith3/4Genablednetworkingcapabilityallowdevicesto transmitimagecapturestobasestationswhere image-recognitiontoolshelpdistinguishpoachers fromprimates(CITE).Acousticsensorsinterfaced withlocalmobilephonenetworksalsooffernear real-timetransmissionofdetectedsounds(Aide etal.,2013).

Besidesmerelydetectinganimalmovement, manymovement-relatedquestionsconcerndirectionality,speed,andfitnesscosts.Forexample, biologgersnowrevealanimalmovementinthree dimensions,integratingaccelerometers,barometers,andgyroscopes(Allanetal.,2018).Once limitedtoterrestrialsystems,biologgersarenow employedtoinvestigatethephysiologicalmechanismsthatinfluencelifehistoryandpopulation changes,evenforgloballydistributedpopulations.

Theycansenseanddocumentnearlyallaspectsof ananimal’smovements,fromwhenafishopensand closesitsmouth(Viviantetal.,2014)tothenutritionalgeometrythatinfluencesmarinemammaldiving behaviour(Machovsky-Capuskaetal.,2016).

Forthemostpart,sensorsaresmall,lightweight, satellite-based,andoftendonotrequireinvasivemethodsindeployment(Bogradetal.,2010). Largespeciesfromthetropics(Yangetal.,2014) tosmallerspeciesatthepoles(Kuenzer,2014) canbemonitoredfromspaceusingsatellitetechnology,expandingthegeographicscopethrough whichweinvestigaterelatedquestions.As Wilmers andcolleagues(2015) summarizedinareviewof biologgingdevices,‘Nearlyallbiologicalactivity involveschangeofonekindoranother.Increasinglythesechangescanbesensedremotely’.Thelast decadeshavetransformedourabilityfrommerelyidentifyinganimallocations,tonowmonitoringtheirmovement,socialinteractions,andreconstructingbehavioural,energetic,andphysiological statesfromafar.Chapter 6 describessomeofthese innovativebiologgingtoolsthatareimprovingthe resolutionandtypeofdatathatwegatherfrom animal-bornedevices.

Inadditiontoinformationextractedfromloggers, dataalsocomeindirectlyfromevidenceleftbehind byanimals;forexample,hair(Mowat&Strobeck, 2000; Macbethetal.,2010),faeces(Muehlenbeinetal.,2012),andtools(Stewartetal.,2018). Theemergingfieldofconservationphysiology (Wikelski&Cooke,2006),whichcentresaround neuro-endocrinestressindicatorsandtheirinfluencesonbehaviour,canrevealwildliferesponses toenvironmentalchange,fromforestlosstowater temperaturetotourism(Ellenbergetal.,2007; reviewedin Acevedo-Whitehouse&Duffus,2009). Faeces-extractedDNAhasalsolongbeenan importanttoolforconservationscientists.DNA analysescanrevealabundanceandsurvivorship (Sitkadeer—Brinkmanetal.,2011;pronghorn— Woodruffetal.,2016),populationdynamics,and densityvariabilityacrosssites(coyotes—Morinet al.,2016),amongotheraspects.Historically,DNA extractionandhormonalassayswereconducted inlaboratoriesfarremovedfromfieldstations andrequiredresearcherstopreserve,store,and exportsamples.Theserestrictionshaveincreasedin

recentyears,combinedwithpressuretobuildlocal capacityofrangecountryscientistsinmolecular analyses(O’Connelletal.,2019).Chapter 7 explores fieldlabsandhowmuchofthisanalyticalworkcan beconductedwithportablefieldkits.

Asthisvolumemakesclear,conservationists havetraditionallyemployedmorphologicaland behaviouraldatacollectiontechniquesusingdirect observations,aswellassensorsplacedonsatellites, cameras,acousticunits,andevenanimalsthemselves.Moreover,fordecadesanadditionalfocusof censusingpopulations,assessinghealth,andtrackingmovementusingindirectevidencehasfocused ontheDNAextractedfromhairorfaecesfrom individualorganisms.However,byinventorying farlargeramountsofDNAintheenvironment,that is,eDNA,manymorequestionscanbeaddressed, namelyaboutpastandpresentbiodiversity(Beng& Corlett,2020).EnvironmentalDNAisanimal geneticmaterialoriginatingfromthehair,skin, faeces,orurineofanimalsbutthathasdegraded andcanbeextractedfromwater,soil,orsediment (Thomsen&Willerslev,2015; Beng&Corlett, 2020).Likemostoftheaforementionedtechniques, usingeDNAisnon-invasiveandsamplecollection requireslittlespecialisttechnicalortaxonomic knowledge(liketheothersaswell,analysesare highlytechnicalandcomplex).Moreover,sampling entiresystemsincreasesthelikelihoodofcapturing DNAofcrypticorelusivespecies,aswellasfor thoseinwhichmorpho-typesaresimilarandthus potentiallydifficulttodecipherfromobservation only.Finally,unlikeusing,forexample,drones oracousticsensors,whenrainorwind,respectively,impairssampling,eDNAcollectionisnot constrainedbyweatherconditions(Thomsen& Willerslev,2015).

BengandCorlett(Beng&Corlett,2020)summarizetheconservationapplicationsofeDNA,from beingafast,efficientmeansofmonitoringpopulationdynamicsoncommunityorspecieslevelsas wellasameanstomaptheirdistributionacross vastspatialscales,toidentifyingbiologicalinvasionsandassessingthestatusoferadicationmeasures.eDNAisalsousefulinrevealingpastand presentbiodiversityandtrophicpatternswithin seawater,freshwater,andevenpermafrostmaterial datingbacktensofthousandsofyears(Willerslev

etal.,2014).Inthatsense,eDNAoffersatemporal rangethatothermethodscannotandwithprices decliningisanon-invasivewaytovastlyincrease thespatialscaleofbiodiversityassessment,while simultaneouslymaintaining—ifnotincreasing— species-specificresolution.

Theexpansionoftechnologicaltoolsforconservationpracticeisnotlimitedto what dataare collectedbutalso how theyarecollected.Traditionally,paperandpensufficedforbehavioural observationsofwildlifeandalsoforrecordingsurveydata.Theproliferationofsmartphones/tablets andapplicationsassociatedwithdatacollectionand integrationhaveimmeasurablyimprovedthenow seeminglyantiquatedprocessofrecordingdataby handforeventualtranscriptionintodigitalformat. Theappearance/vanishrateofappsinapp/play storesmakeacomprehensivechapterimpossible towrite.Nonetheless,Chapter 9 describessomeof themorecommonapplicationsrelevantforconservationscientists,comparesusability,price,and applications.Nearlyalloffertheadvantageofbeing customdesignable,streamlinedforspecificdata collection,andcloudaccessibleforremoteaccess toground-trutheddata.Perhapsthemostwellknownapp,andmostpervasivelyusedinspecies protection/conservationmanagementisSMART,to whichwedevoteanentirechapter(Chapter 10), includingnumerouscasestudies(Hötteetal.,2016) thatdemonstratetherolethesoftwarehasplayedin improvingtheefficiencyandefficacyofpatrolsand overallspeciesprotection(Wilfredetal.,2019).

Withthegrowthindatacollectiontechniques andstoragecapacitieshavecomebetter,faster,and moreautomatedwaysofsievingthroughdatato identifypatternsandrelationshipsbetweenvariablesofinterest.Historically,largedatasetswere plaguedwithdelaysbetweendataacquisition,analysis,andsubsequentinterpretation.Now,weare inthemidstofanotherwaveoftransformational improvement,withautomatedprocessingofbig datausingcomputervisionand/ordeeplearningto streamlinedatamanagementandpatternextraction (Miaoetal.,2019).Computervisionisaninterdisciplinaryfieldofartificialintelligence(AI),whereby computersusepatternrecognitiontodecipherand interpretthevisualworld,alsoknownasmachine learningandobjectclassification.Machinelearning

techniqueshavetransformedtheextenttowhich wecantraincomputerstoidentifyobjects,patterns, species,andfaces,amongothers(Norouzzadeh etal.,2018).Thesedatacanhelpidentifyspeciesand insomecases,countindividuals(Seymouretal., 2017)atnear-identicalaccuracylevelstohumans, butfarfaster.Moreover,resultingdatacaninform— ifnotguide—groundteamsthatmayneedtoact urgently.Forexample,radarandopticalsatellites canprovidedailyscanningoftropicalforestsat 5–20mresolutionandrelayresultsthatrevealillegallogginginnear-real-time(Lynchetal.,2013)to groundteams;picturesandcoordinatescanbesent tosmartphonesforimmediateaction.

Resolutioninbehavioural,physiological,and ecologicaldataispromptingaparallelsurgeinpartnershipstobridgeadata-richscientificworldwith industriesthatcanhelpsupportnecessaryanalyses.

Microsoft’s‘AIforEarth’platformusescomputer visiontechniquestoclassifywildlifespeciesand deeplearningtoautomatesurveydata.Asimilar collaborationbetweenHewlett-PackardandConservationInternationalresultedin‘EarthInsights’— softwaredevelopedtomonitorendangeredspecies (Joppa,2015).Nearreal-timeresultsofthistypeof informationacrossawidescale,whetheronanimal (Wall,2014)orpoacher(Tanetal.,2016)movements, offermanagersthepotentialtoactimmediately tomediatethreatsandprotectwildlife.Thatmay resultinincreaseddeploymentofspecificdeterrents (e.g.fencesforelephants),targetedpatrols,oradditionalsurveillancetovulnerableareas.Insummary, whereastheethicalconsiderationsforthesetechnologicaltoolsarefarbehindindevelopment(see next),insomeways,theanalyticaltoolsareway ahead,fuelledbypartnershipsandinterdisciplinary collaborations(Wilberetal.,2013; Sheehanetal., 2020).Theimportance,diversity,andcontributions ofcomputervisionarediscussedinChapter 11

Aswithnearlyalltechnologicalrevolutions,the socialtoolsthatarerequiredtoaccompanysuch innovationslagbehindthephysicaltoolsthemselves.Droneimagery,acousticsensors,andcameratrapsareoftendesignedtorevealdataon elusiveorcrypticanimals.Eitherincidentallyor maliciously,metadatathatmaycompromisepeople, security,andprivacyarethusvulnerabletobeing exposed.Theprogressneededtoadvanceaparallel

advancementinsocialethicsrequirespeoplenot justfamiliarwiththetechnologyanditspotential,butalsophilosophyandsociology.Chapter 12 exploresquestionsaboutwhohasaccesstothese data,howshouldtheybeshared,andhowwe weighscientific,environmental,andempiricalbenefitsagainstsocialcosts.

Wehopetohavedemonstratedthevastreach oftechnologyincontemporaryconservationchallenges,withcontinuingimprovementsinsensor qualityandcapability,aswellaspoweranddata storage,amongothers—allwhilepricesgenerally decline.Improvementsindataresolutionarekey toexpandingthetypesofquestionsthatwecan ask.Forexample,sub-onemetreresolutionofsatelliteimagerynowallowsforquestionsintobotanical diversity,absoluteabundance,andindicesofproductivityforindividualplants.Applicationofsuch imageryisusefulwhenidentifyingspecificthreats (e.g.expansionofoilpalmtrees—Srestasathiern& Rakwatin,2014)ortoquantifymosaichabitats (Gibbesetal.,2010),too.Thefinalchapter(13) describesthefutureofconservationtechnology, highlightinghowincrementalenhancementsofcurrentmethodsandalsoinnovativemethodswill guidehowweprotectbiodiversitygoingforward.

Inclosing,acomprehensivereviewofthetechniquesandassociatedscientificquestionsatthecore ofconservationtechnologyisbeyondthescopeof anysinglevolume.Instead,herewehaveselected whatweconsidertobesomeofthemostcommonly used,important,andapplicabletoolsinconservationtechnology.Ineachchapter,theauthorsare expertsinthefieldandreviewwhatisknownand whatiscurrent.Weusecasestudiestoexemplify howthetoolsareappliedanddiscussthelimitationsaswellaswhatliesahead.Wefocuson somerecent,pioneeringmethodsofdatacollection andalsodevelopmentstomoreestablishedwaysof datacollection.Wehopethatthisvolumecaptures theinnovativewaysthattechnologycontributesto, improveson,andultimatelydrivescontemporary conservationpractice.

References

Acevedo-Whitehouse,K.,&Duffus,A.L.J.(2009).

Effectsofenvironmentalchangeonwildlifehealth.