Computational Models of Reading

A Handbook

Erik D. Reichle, PhD PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY

MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Erik D Reichle 2021

All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Reichle, Erik D., author.

Title: Computational models of reading : a handbook / Erik D Reichle

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2021. |

Series: Oxford series on cognitive models | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020025887 (print) | LCCN 2020025888 (ebook) | ISBN 9780195370669 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190669096 (epub) | ISBN 9780190853822

Subjects: LCSH: Reading, Psychology of | Reading Computer programs | Word recognition | Human information processing

Classification: LCC BF456.R2 R345 2021 (print) | LCC BF456.R2 (ebook) | DDC 418/ 4019 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020025887

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020025888

DOI: 10 1093/oso/9780195370669 001 0001

As befitting a book about the science of reading, this book is in memory of my father, Paul, who taught me to love both science and reading.

Whoever cannot seek the unforeseen sees nothing, for the known way is an impasse. Heraclitus

Contents

Acknowledgments

1. Introduction

Information-Processing Metaphors

Brief Overview of the Human Information-Processing System

Reading versus Spoken Language and Other Communication

Summary and Conclusions

Chapter Previews

2. Formal Models

What are Formal Models?

Different Approaches to Formal Modeling in Cognitive Science

Process Models

Production-System Models

Connectionist Models

Comparative Examples

How are Models Compared?

Computational Models of Reading

3. Models of Word Identification

Word-Identification Research

Word-Identification Tasks

Learning Effects

Orthographic Effects

Phonological Effects

Semantic Effects

Patterns of Impairment

Strategic Effects

Precursor Theories and Models

Logogen Model

Bin Model

Dual-Route Model

Analogy Model

Parallel-Coding Systems (PCS) Model

Interactive-Activation (IA) Model

Activation-Verification Model

Triangle Model

Multiple-Levels Model

Multiple Read-Out Model

Multiple-Trace Memory Model

Connectionist Dual Process (CDP) Model

Dual-Route Cascaded (DRC) Model

SERIOL

ACT-R Lexical-Decision Task Model

Bayesian Reader

Connectionist Dual Process (CDP+) Model

Overlap Model

Spatial-Coding Model (SCM)

Model Comparisons

Conclusions

4. Models of Sentence Processing

Sentence-Processing Research

Precursor Theories and Models

Augmented Transitional Networks

Sausage Machine Model

Garden-Path Model

Sentence-Gestalt (SG) Model

Simple-Recurrent Network (SRN)

CC-Reader

Probabilistic Parser

Attractor-Based Parser

Constraint-Based Models

Dependency-Locality Theory (DLT)

Cue-Based Parser

Activation-Based Model

Model Comparisons

Conclusions

5. Models of Discourse Representation

Discourse-Representation Research

Precursor Theories and Models

Story Grammars

Kintsch & van Dijk’s (1978) Model

Construction-Integration (CI) Model

Situation-Space Model

3CI-Dynamic Model

State-Space Search Model

Landscape Model

Resonance Model

Langston-Trabasso Connectionist Model

Distributed Situation-Space (DSS) Model

Model Comparisons

Conclusions

6. Models of the Reading Architecture

Eye-Movement Research

Precursor Theories and Models

Gough’s (1972) Model

Reader

Morrison’s (1984) Model

Rayner & Pollatsek’s (1989) Model

Attention-Shift Model (ASM)

E-Z Reader

EMMA

SWIFT

Glenmore

SERIF

OB1-Reader

Model Comparisons

Conclusions

Candidate Reading Architectures

Über-Reader

Word Identification

Sentence Processing

Discourse Representation

Peripheral Systems

Simulations

Simulation 1: The Identification of Words

Simulation 2: The Parsing of Sentences

Simulation 3: The Reading of Sentences

Simulation 4: The Representation and Recall of Discourse

Limitations of Über-Reader

Conclusions

APPENDIX A ACT-R

APPENDIX B 3CAPS

APPENDIX C CONNECTIONIST MODELS

APPENDIX D MODELS OF EPISODIC MEMORY REFERENCES

INDEX

Acknowledgments

I have many people to thank for helping make this book possible. First and foremost, I would like to thank my two former mentors, Keith Rayner (who much to the remorse of his friends and colleagues, passed away in 2015) and Sandy Pollatsek. I was extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity to work and become friends with Keith and Sandy since first meeting them in graduate school at UMass, Amherst in 1990. The generosity of these two men cannot be overstated; both taught me volumes about the psychology of reading and science more generally, and Sandy in particular was instrumental in teaching me much of what I know about computer modeling. I also am indebted to Keith for both putting me in contact with the people at Oxford University Press and for encouraging me to write this book. I’m only sorry that he was not able to see the final product.

I also would like to thank the sources of financial support that made the writing of this book possible. First and most importantly, I would like to thank the Hanse Institute for Advanced Study for its very generous financial support. A significant portion of the first draft of this book was written while I was on sabbatical at the Hanse Institute, in Delmenhorst, Germany, during the first five months of 2008. I can honestly say that, without that time away from my “day job,” this book would not have been possible. And in particular, I would like to thank Wolfgang Stenzel, the Research Manager for Neuroscience and Cognitive Sciences, and Gerhard Roth, the former Director of the Hanse Institute, for making the fellowship available to me, and for being such gracious hosts. And of course, I also would like to thank my sponsor, Franz Schmalhofer.

In the same spirit, I also would like to thank the Pittsburgh Science of Learning Center. Their financial support allowed me spend time reading the literature on models of word identification, a prerequisite for writing Chapter 3, and also allowed me to develop part of the conceptual foundation that contributed to the contents of Chapter 7. I also would like to thank Charles Perfetti, who encouraged me to apply for the grant, and whose friendship and mentorship have also contributed in significant ways to the completion of this book.

I also would like to thank the many people who helped me over the years and, in so doing, made the writing of this book possible. In particular, I would like to thank Sally Andrews, Ehab Hermena, Michael Hout, Megan Papesh, Keith Rayner, Aaron Veldre, and Lili Yu for reading various drafts of this book and providing me with the invaluable feedback for improving both its readability and content. Additionally, I would like to give special thanks to two people who have, over the years, often challenged how I thought about the psychology of reading: Sally Andrews and Eyal Reingold. It is fair to say that this book would have been different without their influence and friendship. And similarly, I would like to thank my many academic friends and colleagues who, across the chapters of my own life, have helped

me in various ways and thereby facilitated the writing of this book: Jim Anderson, Jane Ashby, Amanda Barnier, Lisi Beyersmann, Anne Castles, Denis Drieghe, Ralf Engbert, Don Fisher, Fernanda Ferreira, Ding-Guo Gao, Steve Goldinger, Barbara Griffin, Simon Handley, John Henderson, Jukka Hyönä, Mike Jones, Holly Joseph, Barb Juhasz, Johanna Kaakinen, Rachel Kallen, Sachiko Kinoshita, Reinhold Kliegl, Saskia Kohnen, Jan-Louis Kruger, Patryk Laurent, Roger Levy, Xingshan Li, Simon Liversedge, Yanping Liu, Tomek Loboda, Joe Magliano, Lyuba Mancheva, Gen McArthur, Vicky McGowan, Avril Moss, Wayne Murray, Kate Nation, Antje Nuthmann, Ruano Perilla, Ralph Radach, Ronan Reilly, Mike Richardson, Jonathan Schooler, Elizabeth Schotter, Heather Sheridan, Kerry Sherman, Richard Shillcock, Natasha Tokowicz, Tessa Warren, Mark Wheeler, Sarah White, Carrick Williams, Gouli Yan, and Chin-Lung Yang. Quite a few of the aforementioned are new friends and colleagues at Macquarie University, and I have to say I am very fortunate to have ended up working with such a welcoming and distinguished group of people. If my places of employment correspond to the setting of my life’s story, then the final chapter certainly promises to be the very best.

Finally, I would like to thank my editor at Oxford University Press, Frank Ritter, for his unwavering support and perhaps more importantly patience during the years that were necessary for me to write this book. And similarly, I also would like to thank the small army of people (Rajeswari Balasubramanian, Martin Baum, Joan Bossert, Joyce Helena, and Phil Velinov) who helped me edit and assemble the many pieces of this book, which was no small task. And last but certainly not least, I would like to thank Richard Carlson, Steve Crocker, Jay McClelland, and most especially Sashank Varma, for your constructive feedback on the penultimate version of this book; your many suggestions proved invaluable for helping me shape the book into its final form. For that, you have my sincere appreciation.

To completely analyze what we do when we read would almost be the acme of a psychologist’s achievements, for it would be to describe very many of the most intricate workings of the human mind, as well as to unravel the tangled story of the most remarkable specific performance that civilization has learned in all of its history.

Huey (1908, p. 6)

1 Introduction

A LITTLE OVER a century ago (as of this book’s writing), Edmund Huey made the case that, of all mankind’s accomplishments, the invention of reading and writing were the most remarkable, effectively making possible all of the advances in culture and technology that we today take for granted. For millennia prior to the invention of reading and writing, our progress was limited to what could be passed on from one generation to the next through rote memorization and oral transmission. In the five and a half millennia since their invention, our species has used reading and writing to make remarkable steps toward understanding nature and developing technologies that, even a few generations ago, would have seemed impossible. Through the written word, we have documented these accomplishments and described our aspirations for the future.

As someone with an appreciation of history, I share Huey’s (1908) belief that these remarkable achievements would not have been possible had it not been for the invention of reading and writing. But as a cognitive scientist with the goal of understanding and describing how the human mind works, what I find most compelling about Huey’s observations is his insight that to understand the mental processes of reading really would be “to describe very many of the most intricate workings of the human mind.” The truth of this statement reflects the fact that reading, a seemingly trivial activity, engages most of the cognitive systems that are supported by the human brain, including those responsible for vision, attention, memory, and language. It therefore stands to reason that, by making an effort to understand what happens during reading, we will gain a better understanding of the human mind.

Before proceeding any further, however, it is first necessary to warn readers who have strong backgrounds in cognitive psychology or a specific interest in computational models of reading that this chapter is only intended to provide a brief introduction to the topics that will be discussed at length in subsequent chapters. As such, this chapter will provide an overview of cognitive psychology, including brief discussions of its methods and what has been learned about the human mind and reading. Because of the introductory nature of this chapter, readers with more advanced backgrounds or specific interests may wish to skip it, knowing that their understanding of subsequent chapters should not be hindered.

As will become clear in this chapter, this book is about the human mind, and more specifically, what the study of reading can teach us about how the human mind works. To give a broad overview of both, let’s briefly consider what is happening inside of your mind/brain1 as you are reading these words. As your eyes move across this line of text, they make very rapid ballistic movements, called saccades, that move your high-acuity center of vision from one viewing location to the next. In between these saccades, your eyes remain relatively stationary for brief intervals of time, called fixations, so that visual features on the printed page can be propagated from your eyes to your brain for further processing. Of course, all of this happens at a fairly remarkable rate; the saccades generally take around 20 ms to 35 ms to execute, and the fixations are generally between 200 ms and 250 ms in duration, but can vary from 50 ms to 500 ms. Although most saccades move the eyes forward during reading (an average of 7 to 9 character spaces in English), there is also considerable variability in saccade length, and about 10% to 15% of the saccades are regressions that move the eyes back through the text. Because vision is largely suppressed during saccades (Matin, 1974; Riggs, Merton, & Morton, 1974), reading has been described as a “slideshow” in which the information available from each fixation is viewed for about a quarter of a second before the eyes move to a new viewing location to obtain information from the next “slide” (Rayner & Pollatsek, 1989).

As mentioned, the visual information acquired during each fixation is propagated from the eyes to the cognitive systems that convert the little lines and squiggles first into the graphemes (i.e., letters, characters, and punctuation marks) so that information about word pronunciations and meanings can then be accessed from memory. The cognitive systems that are responsible for language then integrate the meanings of individual words with prior linguistic and conceptual knowledge to construct the mental representations that are necessary to understand the text. Although the precise nature of these representations remains largely a mystery, they must be both rich and varied as evidenced by, for example, a bit of introspection about the nature of the representations evoked when reading poetry versus a set of instructions to assemble furniture.

These discourse representations are constructed in short-term memory, which roughly corresponds to our immediate sense of awareness, from linguistic and conceptual knowledge that has already been stored in long-term memory, which roughly corresponds to what most people think of as being “memory” (i.e., the repository of our experiences, knowledge, and skills). Some of these newly constructed text representations will then be transferred from short-term to long-term memory so that they can later be remembered (e.g., as necessary to understand subsequent text). And all of these activities are controlled by the cognitive systems responsible for initiating and monitoring one’s behavior; during reading, these control systems allow us to attend to the text rather than other potential distractions. Thus, with the help of these control systems, and after several years of education and practice, the cognitive systems that support reading become capable of performing their respective tasks in a largely automatic and highly coordinated manner, affording the rapid comprehension of text that is indicative of skilled readers.

It goes without saying that this brief description of what happens in the mind of a reader is consistent with Huey’s claims about the complexity of reading and how its analysis might

further our understanding of the human mind. The purpose of this book is to contribute to this effort. Although there are already several books on the psychology of reading (e.g., Crowder & Wagner, 1992; Dehaene, 2009; Downing & Leong, 1982; Just & Carpenter, 1987; Mitchell, 1982; Perfetti, 1985; Rayner & Pollatsek, 1989; Rayner, Pollatsek, Ashby, & Clifton, 2012; Robeck & Wallace, 1990; Seidenberg, 2017; see also the edited volume by Treiman & Pollatsek, 2015), this book will adopt a unique strategy; rather than focusing exclusively or even primarily on those empirical findings that shed light on the cognitive processes involved in reading, I will focus mainly on the computational models that have been developed to describe and explain those cognitive processes. For those who lack familiarity with computational models, this term refers to a theory that, rather than being a verbal explanation of some phenomenon, is instead an explanation that has been implemented using mathematical equations and/or a computer program. There are many advantages of such models over more traditional verbal theories, with the primary one being that computational models allow a degree of descriptive precision and scientific rigor that are simply not possible with verbal theories. This is particularly true in domains of science in which the phenomena being studied are highly complex (e.g., weather systems) or comprised of components that interact in complex ways (e.g., different species in an ecosystem). A more detailed discussion of what computational models are and why they are invaluable to understanding the human mind will be presented in the next chapter. Before doing this, however, it is first important to introduce the dominant metaphor that is used to think about and describe the human mind the information-processing metaphor. I will then use this metaphor as a framework for describing some basic characteristics of human cognition. With that background, I then will close this chapter with a brief discussion of what reading is, and how it differs from both spoken language and other forms of communication.

INFORMATION-PROCESSING METAPHORS

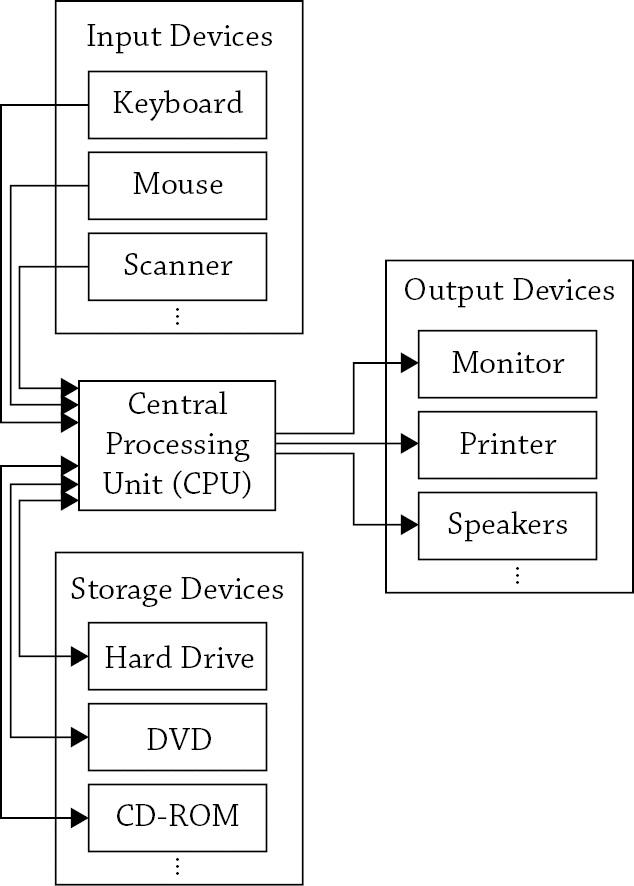

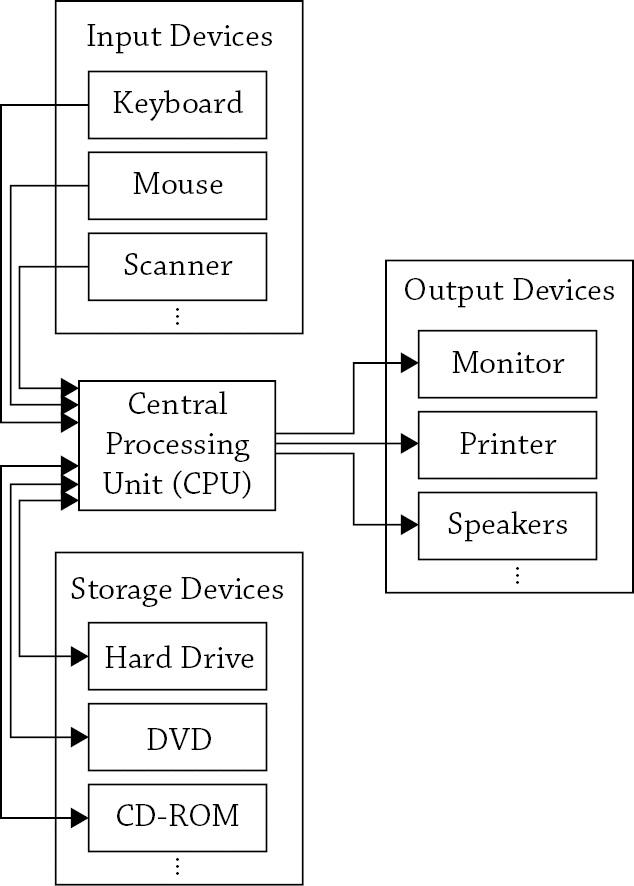

Much has been learned about human cognition during the last 50 years. This knowledge has emerged from a multidisciplinary field called cognitive science (Posner, 1989). The main goal of this field of study has been to understand the human mind, and in so doing, it has borrowed insights and methods from a number of other, more traditional fields of study, including cognitive psychology (i.e., the branch of experimental psychology that studies human cognitive processes; Neisser, 1967), computer science, neuroscience, linguistics, anthropology, and philosophy. These fields have provided important new metaphors for describing how the mind works. Chief among these metaphors has been the digital computer. Although anyone reading this book will know what computers are and will have had at least some experience using computers, the “mind-as-computer” metaphor requires some background information about what computers are and how they work. At their most basic level, computers are physical devices for storing and manipulating information. A computer consists of: (1) some type of “memory” device (e.g., a hard drive) that can hold large amounts of information for indefinitely long periods of time (see Figure 1.1); (2) a set of instructions or programs for accessing this information and then doing something with it; (3) a central-processing unit (CPU) that holds some limited amount of data, typically a program

and whatever data the program is using; and (4) various peripheral input and output devices (e.g., monitors, keyboard). Both the program and the data consist entirely of binary digits, or “bits” of information composed of sequences of electrical pulses that can be conceptualized as corresponding to 1’s and 0’s. This means that whatever information is entered into the computer through input devices, stored in the computer’s memory, or made available from output devices ultimately consists of nothing more than 1’s and 0’s. These binary sequences are manipulated (i.e., their values are changed) at extremely rapid rates (often more than a billion operations per second) by other binary sequences (i.e., computer programs) that specify those manipulations.

FIGURE 1 1 The components of a digital computer The central processing unit, or CPU, uses programs to manipulate information that it receives from peripheral input devices and/or storage devices (e.g., a hard drive). The programs are used to create new information and/or to control output devices All of the information used by the computer, including its programs, consists of sequences of binary digits (i.e., 1’s and 0’s).

Of course, this description of what a computer is and how it works is an oversimplification. For example, computers often have different input and output buffers that maintain quantities of information for brief periods of time (e.g., images that are about to be displayed on the monitor). These buffers allow a computer to run more efficiently by temporarily holding information that would otherwise have to be maintained in the limitedcapacity CPU, thereby freeing the CPU to perform other tasks. Thus, the computer’s architecture, or the precise manner in which the input/output devices, buffers, CPU, and long-term storage devices (e.g., a hard drive) are configured together, is what determines how the computer operates and the types of tasks it is capable of performing.

Another important fact about computers is that, although both the programs and data that they operate upon are composed of 1’s and 0’s, the humans who write the computer programs only rarely write programs using this low-level machine language; computer programmers instead write their programs in higher-level, more abstract programming “languages” (e.g., Basic, C++ , Java) that are designed to be intelligible to humans. For example, in the Java programming language, the command to set some variable Y equal to the value of another variable X raised to the second power is:

Although this command might be opaque to anyone uninitiated to Java, it is actually quite simple. The command is a predefined function that takes two arguments, a base number, a, and an exponent, b, and then returns the value of the base number raised to the exponent. Computer programs consist of these types of instructions, often arranged into long sequences containing thousands of individual commands. Before the programs can actually be executed, however, they first have to be translated by another type of program, called a compiler, from the high-level language used to write the program into the machine language (i.e., the 1’s and 0’s) that is used by the computer. Thus, in a very real sense, computer programs are instantiated on two levels: the binary sequences of 1’s and 0’s that are stored and manipulated by the physical devices that are the computer, and the more abstract instructions that are constrained by the “grammar” or syntax of a programming language. In the lingo of computer engineers, the machine and programming languages are the computer’s software, while all of the physical components are the computer’s hardware.

With this overview of what a computer is and does, it is now possible to discuss how the computer has been used as a metaphor for the human mind. This metaphor is actually twofold. First, cognitive scientists have recognized that the mind is like a computer in that both have the capacity to take in, store, and manipulate information. The mind can thus be compared to a computer in that both are information-processing systems, although the mind’s architecture might differ in important ways from that of the digital computer (e.g., the mind might use more complex representations). A further extension of this metaphor draws a parallel between the software–hardware distinction in the digital computer and a possible distinction between the cognitive “software” and the neural “hardware” on which the former “runs.” Proponents of this functionalist view have argued that, just as computer scientists

study computer software independently of its underlying hardware, so, too, should cognitive scientists study human cognition independently of its underlying neural systems (Fodor, 1981; see also Flanagan, 1991).

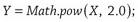

The second computer-as-mind metaphor stems from the recognition that the human mind/brain consists of interconnected information-processing modules (Fodor, 1983) or networks of subcomponents (Bressler, 2002; Mesulam, 1990, 1998) that evolved to perform specific information-processing functions. For example, a considerable amount of physiological and behavioral research indicates that our unitary experience of vision is actually mediated by a network of more than 30 anatomically and functionally distinct brain regions (van Essen & DeYoe, 1995), which each support a specific aspect of vision (e.g., perception of shape, motion; Marr, 1982; Pylyshyn, 2006). Because computer components are also interconnected information-processing systems (see Figure. 1.1), computer architecture also has been used as a metaphor for the mind/brain, with components of the mind/brain being compared to a hard drive or CPU, and others being likened to input/output buffers (e.g., Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968, 1971). According to proponents of this second mind-as-computer metaphor, the goal of cognitive science is to understand how the components of the mind/brain interact in the service of supporting vision, memory, language, and so on (Anderson, 2007).

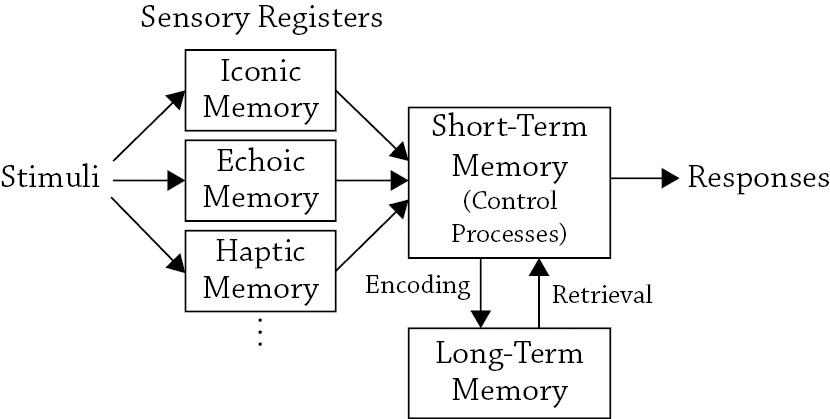

As it turns out, both of the aforementioned mind-as-computer metaphors are useful; as we shall see in upcoming chapters, even weak versions of the metaphors in which the mind/brain is acknowledged to be fundamentally different from the digital computer have proven valuable for thinking about human information processing. In fact, these metaphors have proven so useful that the most widely used or modal model (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968, 1971) of human cognition is transparently related to the digital computer. This model2 is standard fare in cognitive psychology textbooks (e.g., Eysenck & Keane, 2015) because it provides a theoretical framework for thinking and talking about human cognition. For this reason, and because the reading models described in this book build upon this framework, the modal model will be described next.

BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE HUMAN INFORMATION-PROCESSING SYSTEM

The modal model (see Figure 1.2) describes the general architecture of the human information-processing system. The figure shows several memory systems (represented by the boxes) and how information “flows” among these systems (represented by the arrows). As shown, the human information-processing system (or mind) consists of three basic types of memory: (1) sensory registers; (2) short-term memory; and (3) long-term memory. Evidence suggests that these three types of memory are functionally distinct in that they have different operating characteristics and can be selectively impaired through traumatic brain injury (for reviews, see Markowitsch, 1995; Squire, 1986, 1987; Squire & Knowlton, 1995).

FIGURE 1.2. The modal model (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968, 1971). Note the similarity between the model’s architecture and that of the digital computer (see Figure 1.1); both are composed of peripheral buffers, long-term storage devices, and a limited-capacity system that controls information processing

The sensory memory “system” actually consists of several buffers or registers that hold fairly large amounts of sensory information for brief intervals of time. Although there is probably one such system per sensory modality, the two most commonly studied systems correspond to the visual and auditory modalities iconic memory and echoic memory, respectively. Both types of memory are short-lived and are thought to be precategorical because they hold the sensory information in a veridical manner, without reference to information already stored in short- or long-term memory. Much of the early research on iconic and echoic memory was directed toward understanding their basic operating characteristics. As such, this research attempted to answer such questions as: What is the storage capacity of sensory memory? (In other words, how much information can it hold at any given point in time?) How long is this information maintained? And is the information forgotten due to passive decay, or because it is overwritten by new sensory information?

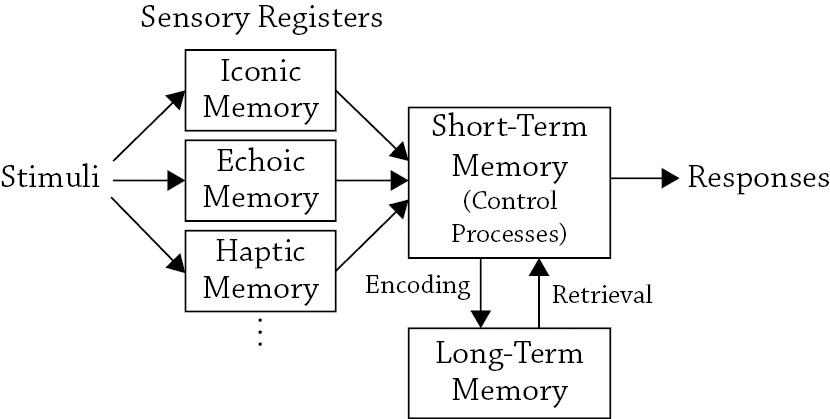

Because this book is about reading and because reading normally involves the visual modality,3 it is important to summarize what has been learned about iconic memory. (This summary is only meant to provide a short description of what iconic memory is and how it has been studied via behavioral experiments; for an in-depth discussion of iconic memory, see Long, 1980.) That being said, Sperling (1960, 1963) conducted the first modern experiments to measure the capacity and duration of iconic memory. These experiments were completed using a tachistoscope, or apparatus with a camera shutter that allows visual stimuli to be displayed for short intervals of time under well-controlled viewing conditions. The experiments also employed an ingenious paradigm depicted in Figure 1.3. This paradigm involved two conditions. In both conditions, subjects viewed 3 × 4 arrays of alphanumeric

characters that were displayed for very short intervals of time (e.g., 25 ms–1,000 ms) and that varied from one trial to the next. The subjects in the first, whole-report condition simply were instructed to report as many characters as possible as soon as the display disappeared. On average, these subjects accurately reported approximately 4.5 of the 12 characters, suggesting that iconic memory holds about 37% of the information contained in the entire visual array.

1.3. A schematic diagram showing the paradigm used by Sterling (1960, 1963) to study human iconic memory. This example shows what happens during a single trial

However, the performance of subjects in the second, partial-report condition indicated that this conclusion was premature. Subjects in this second condition heard a high-, medium-, or low-frequency auditory tone immediately after the character array disappeared, prompting subjects to respectively report the top, middle, or bottom row of characters. Under these conditions, subjects accurately reported slightly more than three characters from any given row. This is remarkable because the reported row was randomly selected from trial to trail and was not cued until after the array had disappeared. The results from the partial-report condition thus indicate that subjects could accurately report about 75% of the characters from any given row, suggesting that the capacity of iconic memory is substantially larger than the estimate from the whole-report condition. The performance difference between the two conditions also suggests that transferring the information from iconic to short-term memory

FIGURE

(as required to report the characters) is the “bottle-neck” that delimits performance in the whole-report condition.

Subsequent research on iconic memory by Sperling and others (e.g., Averbach & Sperling, 1961; Gegenfurtner & Sperling, 1993) has disclosed its brief duration (approximately 250 ms) and revealed that its contents are overwritten by new visual information. Although many details about how iconic memory works are still being debated (e.g., cf., Irwin & Yeomans, 1986; Long, 1985; Yeomans & Irwin, 1985), its existence and basic operating characteristics are fairly well established facts (Long, 1980). And for the purpose of discussing reading models, these basic facts about iconic memory are useful for thinking about how visual input from the printed page might be propagated from the eyes to the human informationprocessing system.

Referring back to Figure 1.2, the next major system in the modal model is variously known as primary (James, 1890/1983), short-term (Brown, 1958; Miller, 1956; Peterson & Peterson, 1959), or working (Baddeley, 1983, 1986, 2001; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Daneman & Carpenter, 1980) memory. This system corresponds to our span of apprehension or our immediate sense of awareness, and it can be most easily described as the system that holds whatever we are consciously thinking about at any given point in time. For example, when reading this sentence, you will encounter the word “tiger,” which then causes that word’s pronunciation and meaning to become active in short-term memory. (This information was retrieved from long-term memory, which as will be discussed shortly is the repository of our experiences, knowledge, and skills.) Despite the fact that this seems to happen with little or no effort, the perceptual and cognitive processes that allow printed words to be identified are extremely complex and consequently not well understood (as will be evident in Chapter 3).

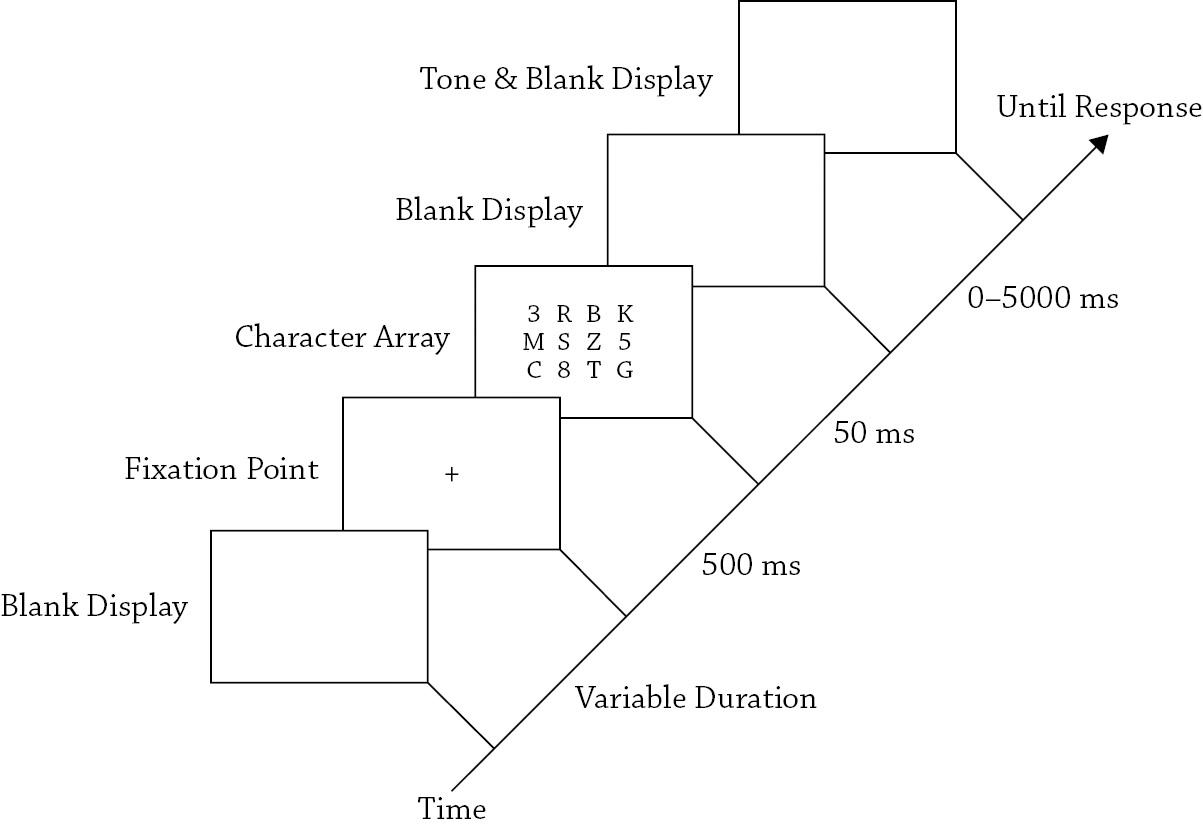

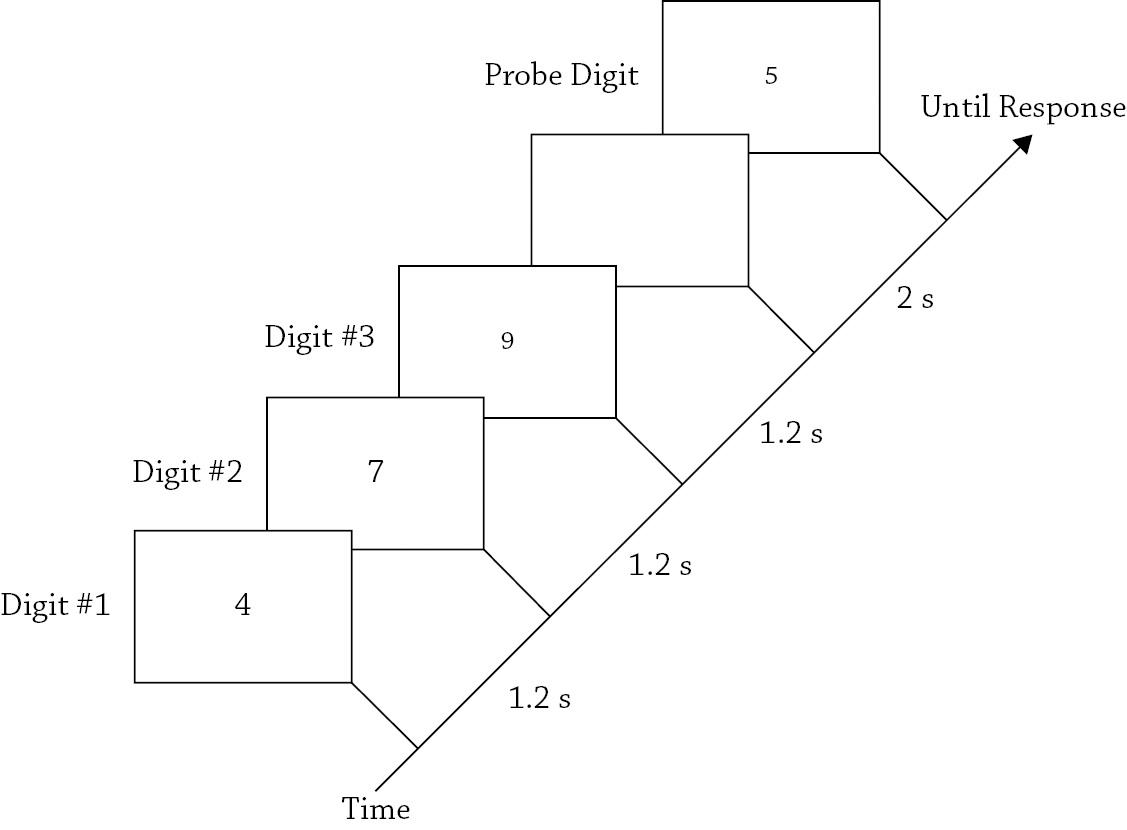

As was true of iconic memory, early research on short-term memory was mainly directed toward measuring its capacity and duration (Miller, 1956), and understanding why information in short-term memory is forgotten (Brown, 1958; Peterson & Peterson, 1959). Subsequent efforts also were directed toward understanding how information in short-term memory is accessed in the service of making overt responses, the nature of the representations that are maintained in short-term memory (e.g., whether they are sound- or meaning-based; cf., Conrad, 1964; Wickens, 1972), and whether short-term memory is a unitary system or composed of interacting subsystems (Brooks, 1968). Again, to give a sense for how this type of empirical research is done, and because short-term memory plays a prominent role in computational models of reading, I will briefly describe one seminal experiment that addressed the question: How is information accessed from short-term memory? Sternberg (1969) addressed this question using the paradigm in Figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.4. A schematic diagram showing the paradigm used by Sternberg (1969) to study how humans access information from short-term memory This example shows a single trial in which three digits are presented (i e , set size = 3) and the probe digit is not in the short-term memory set (i.e., the correct response is “no”).

During each trial of Sternberg’s (1969) experiment, subjects would first see a set of 1–4 random digits (e.g., “4,” “7,” and “9”) with instructions to quickly remember them (i.e., encode them into short-term memory) before seeing a probe digit (e.g., “5”) that might be one of the digits in short-term memory. The subjects’ task was to indicate via button presses whether the probe digit was one of the digits in short-term memory. Although the task might appear to be too simple to be informative, Sternberg was able to make inferences about the nature of short-term memory retrieval by examining the patterns of response times for “yes” versus “no” trials, and how these varied as a function of the set size, or number of digits being held in short-term memory.

To understand how one might do this, it is important to think about the cognitive processes required to perform the task. Upon seeing a probe digit, it first must be encoded so that it can be compared to the digit(s) in short-term memory. Then, depending upon the outcome of these comparisons, a decision is made to respond “yes” or “no” and the appropriate response then executed. Although the time required to complete each of these processes would not be expected to change as a function of set size, one might predict each additional digit in short-

term memory would require an additional comparison, thereby affecting the comparison time as a function of set size. (The assumption here is that each comparison requires one of the digits to be accessed from short-term memory.) Furthermore, depending on precisely how the comparisons are completed, one might predict one of three possible patterns for response times.

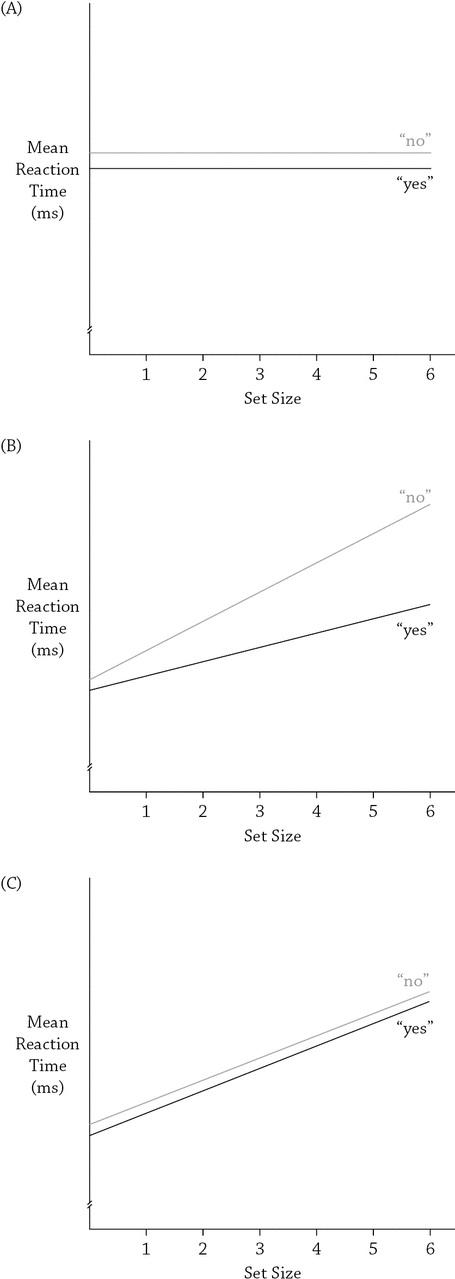

In the simplest possible case (shown in Figure 1.5A), the probe digit is simultaneously compared to all of the digits in short-term memory to determine if there is a match. With this type of parallel search, the times required to respond “yes” or “no” are not affected by the number of comparisons because they are completed concurrently, causing the slope of the response-time functions to be fairly flat. Of course, “no” responses might require more time than “yes” responses, but like the “yes” responses, the latencies to respond “no” should not be affected by the number of comparisons. (This type of parallel search is similar to searching for a green apple among a small bowl of red apples; the green apple simply “pops out,” allowing it to be rapidly located irrespective of the number of red apples.)