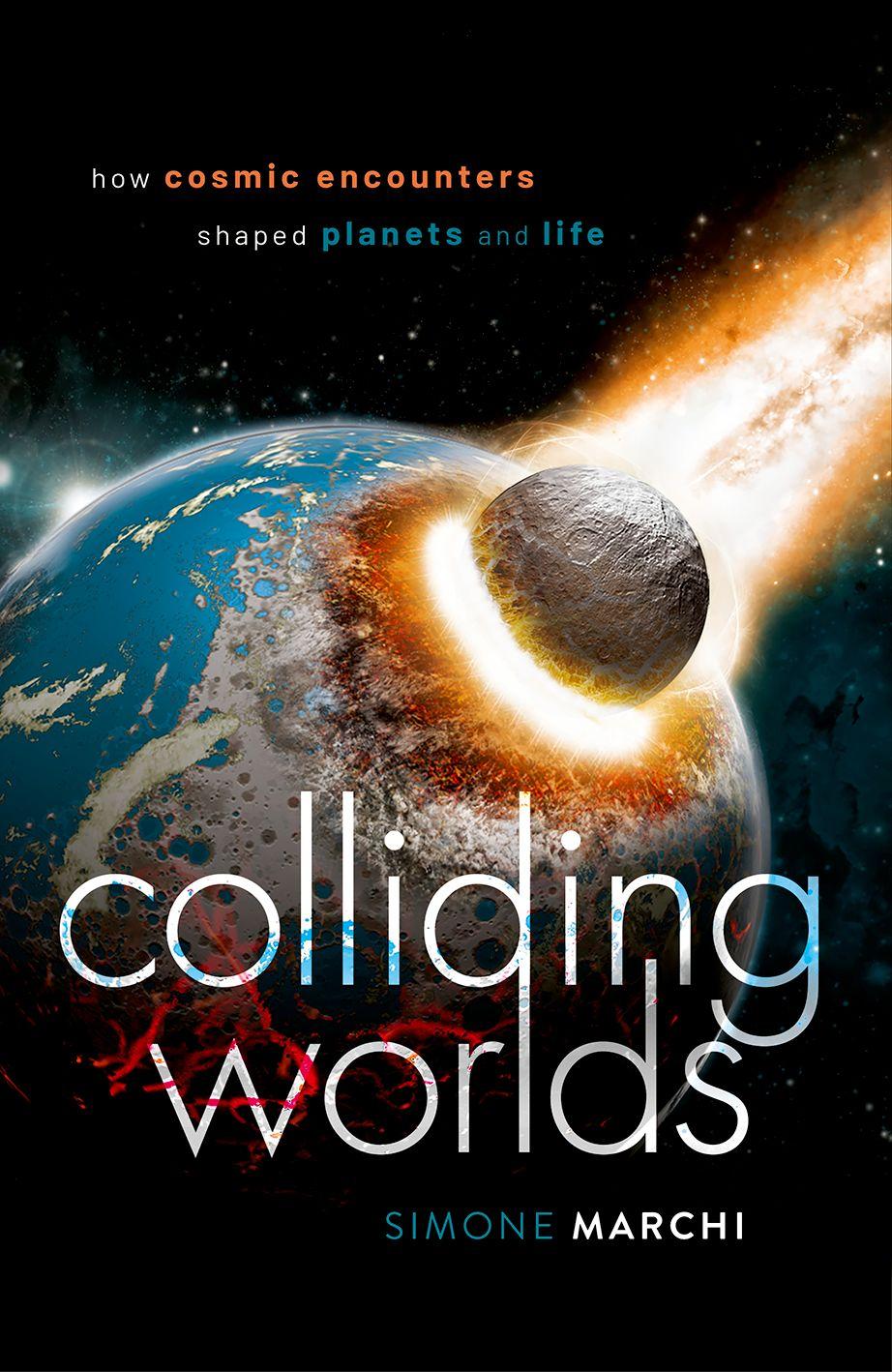

PREFACE

Colliding Worlds reveals the untold story of how violent cosmic collisions shaped the formation and evolution of rocky planets, including our own. It is now well established that our Moon was born in a colossal collision, but more subtle and often counterintuitive consequences of ancient collisions are emerging, thanks to sophisticated models of Solar System formation, the analysis of ancient rocks both from Earth and extraterrestrial, and most exciting of all, the results of space missions to Mars and to several asteroids.

The signs of cosmic collisions are widespread: anywhere we lay our sight on a solid planetary surface, from the innermost planet Mercury to asteroids such as Vesta and Ceres, we find countless craters that have resulted from the impact of rocks from space. And rocks from the Moon, Mars, and asteroids that land on Earth as meteorites bear signs of ancient catastrophes. The Earth must surely have had its fair share of big impacts. But nature plays tricks on us, and our geologically active Earth has erased traces of these violent events.

The painstaking work of geologists, geochemists, and planetary scientists shows that the Earth was not immune to these catastrophic events; quite the contrary. Collisions and lots of them punctuated the evolution of our planet. We humans owe our existence to a random asteroid that played havoc some 66 million years ago, famously causing the extinction of most dinosaurs, among 75 percent of all living species. But there is more to the story than meets the eye. This book presents the latest research, drawing on the data obtained by Nasa’s Dawn mission to the asteroids Vesta and Ceres, by the Mars rovers, and

missions to Mercury and Venus, as well as the exciting findings from ground and space telescopes concerning systems of exoplanets. With further new space missions planned for the 2020s, the future will certainly bring new discoveries, but the overall picture of the violent early days of the Solar System is now coming into focus, and that is the story I will recount here. There is much fascinating detail I have had to leave out, but keen readers are directed to the endnotes, which provide some additional information and references.

The story told in these pages follows closely my own scientific research, taking the present form thanks to researchers from different disciplines who share a common interest on these fascinating topics. I could not have written this book without their genuine interest. Aspects of the book have been shaped by discussions with, among others, Jeff Andrews Hanna, Jim Bell, Ben Black, Bill Bottke, Robin Canup, Clark Chapman, Robert Citron, Rogerio Deienno, Cristina De Sanctis, Nadja Drabon, Lindy Elkins Tanton, Luigi Folco, Laurence Garvie, Vicky Hamilton, David Kring, Hal Levison, Don Lowe, Tim Lyons, Tyler Lyson, Hap McSween, Alessandro Morbidelli, David Nesvorny, Cathy Olkin, Ryan Park, Silvia Protopapa, Carol Raymond, Karyn Rogers, Raluca Rufu, Everett Shock, John Spencer, Kleomenis Tsiganis, and Rich Walker. Thank you all for your advice on specific aspects. Needless to say, any errors remaining in the final text can be laid at my door. A special thank you to the late Jay Melosh, a pioneer in collisional processes, who provided a supportive review in the early stages of this project.

A big thank you goes to my editor, Latha Menon, for having believed in this project, and for outstanding professional guidance throughout the writing of this book. Thanks to Jenny Nugée for helping sort out the graphical aspects of the book. I am indebted to Tyler Lansford for kindly reading the first draft of the

preface · ix book and taking on the daunting task of making sense of my English.

I kept the writing of this book secret, even from close friends. They now ask, how did you find the time? I wrote it thanks to an assiduous, almost maniacal, approach. To cope with the vast scope of the book amid busy life, I set aside all the Sunday mornings over the span of a year, the alarm clock set at 6 a.m., regardless of whichever part of the world I laid down the previous night. For this, I am grateful to my wife, Cristina, who lovingly and unconditionally supported my endeavor by reading early drafts, discussing broader implications, and putting out family fires when needed, allowing me to concentrate on my book. The bulk of the writing took place at Trident Booksellers & Café in Boulder, and was fueled by an untold amount of coffee. On many mornings, I could be found writing these pages tucked away at a small table at the back, amidst shelves of secondhand books. I delivered the manuscript just as the whole world was starting to shut down for the COVID 19 pandemic.

Enough said.

Simone Marchi

Boulder, Colorado March 2021

BORN OUT OF FIRE AND CHAOS

We certainly see the surface of the Moon to be not smooth, even, and perfectly spherical, [. . .] but, on the contrary, to be uneven, rough, and crowded with depressions and bulges. And it is like the face of the Earth itself.

Galileo Galilei, Sidereus Nuncius, 1610 ad1

Our Earth revolves around the Sun, along with myriad other objects, from tiny atomic particles to giant gaseous planets. The expanse in which the Sun exerts a dominant role defines our immediate cosmic neighborhood, the Solar System. And it’s here that we begin our journey throughout space and time, by posing a seemingly simple question: How did our Solar System, and in particular our own blue-green planet, form? It’s a question that has crossed countless people’s minds throughout the ages and has been pondered by the most renowned philosophers and scientists. While an exhaustive answer is still beyond our grasp, pieces of the puzzle are gradually coming together. It all began some 4.6 billion years ago, with the contraction of a cloud of rarefied gas—mostly hydrogen—and “dust,” as astronomers quaintly refer to tiny solid particles in space. All the

2 · born out of fire and chaos

atoms we find on Earth and other objects in our Solar System come from this tenuous cloud, and yet very little is known about it. Astronomers gain insights by observing similar clouds in our galaxy. Based on these observations, we infer that the cloud from which our Solar System originated could have stretched for some 100,000 astronomical units—one astronomical unit (AU), is the Sun–Earth distance, or about 150 million kilometers, so we are talking of a cloud some 15 trillion kilometers wide.

Under the right conditions, these clouds of gas and dust start to contract due to their own gravity. As our cloud shrank, the density of the gas increased dramatically. In less than a million years—the blink of an eye in astronomical terms—hydrogen gas at the center of the cloud became dense and hot enough to trigger a nuclear reaction, converting the hydrogen to helium, with the release of vast amounts of energy. The Sun was born.

At this stage, the gas at the center of the Sun would have been some 150 times denser than water, or a mind-blowing 20 orders of magnitude (that is, 10 to the 20th power) higher than that of the starting cloud. The rest of the cloud stretched for hundreds of astronomical units in all directions and gradually settled into a disk-like structure—a “protoplanetary” disk—rotating around the newborn star like a gigantic Ferris wheel. The inner parts of the disk were irradiated by the young Sun, reaching temperatures greater than 1,000 °C. But the periphery, shielded by the rest of the disk, received only a tiny fraction of the solar radiation and remained extremely cool, well below –200 °C.

This gradient in temperature along the disk, and the increased gas density as the spinning disk becomes compressed into a thin layer, had important consequences for the next stage of its evolution. A dense disk is an ideal environment in which gas can begin to condense into solid grains, as molecules of water vapor coalesce to the tiny droplets making up fog. Closer to the

Sun, only compounds that are stable at high temperature, so-called refractory elements, could condense, creating dry dust grains. Further out along the disk, volatile elements could also condense, to form icy dust grains. Because of this, the composition of dust in the disk varies as we move outwards from high temperature phases, such as calcium and aluminum-rich grains, to extremely volatile phases, such as nitrogen ice (N2), passing through a rich range of silicates and ices in between. These grains are the seeds of planets, and they highlight a fundamental property of all planet ary systems: dry bodies are to be found close to the parent star; icy ones reside further out. This is the ultimate reason why the rocky Earth is relatively close to the Sun, although as we shall see in Chapter 2, the reality is considerably more complex.

The condensation of dust grains is a necessary first step in the formation of planets (Plate 1). The next is characterized by the growth of dust grains, but just as a sand grain is only the beginning of a pearl, the process is long and tortuous. Under the right conditions, dust grains orbiting the Sun would have come close enough to collide gently and stick together. At this early stage, the relative speed of the grains can be just a few centimeters per second, about a hundredth of a walking pace. In such an environment, sub-millimeter-sized grains can quickly grow to larger aggregates. The exact size of the resulting dust aggregates, called pebbles, depends on the local conditions in the protoplanetary disk, such as the density of dust and gas, which in turn depends on the distance from the star. So the size of the pebbles isn’t uniform across protoplanetary disks. For our Solar System in its early evolution, it may have varied from about 1 mm at Earth distance to 1–10 cm at 10 AU. Let us pause here for a moment. The sticking together of tiny dust grains provides our first example of a collision, a vital process in planet formation, and many more

4 · born out of fire and chaos examples spanning a wide range of energies will follow as our story unfolds.

The growth of dust grains is the start of planet formation, but it’s still a long way from producing full-blown planets. One can imagine that pebbles could grow further by colliding and sticking together, but this is problematic for several reasons. Numerical models and laboratory experiments—yes, physicists do experiments with dust grains!—show that pebbles have a hard time growing to larger sizes.

For a start, larger objects are less prone to stick together, as can be seen if we consider the difference between dust particles, which can easily stick to a wall, and a football, which if thrown at the wall falls to the ground. This is because the tiny forces among grains that cause sticking are less effective at attracting more massive objects. Also, as the size of the pebbles increases, they disturb nearby particles, and their collisions tend to become more energetic, and so more likely to break apart the fragile dusty aggregates rather than accreting them. Ultimately, the growth of larger particles is stalled by disruptive collisions or by scarcity of pebbles as they are lost to breakup and other processes. Indeed, larger pebbles can be efficiently removed from the disk, as the headwind exerted by the gas can perturb their orbits, causing them to spiral inward and end up falling into the Sun. The timescale by which pebbles move closer to the Sun is faster when the particle size reaches about 1 m, at a distance of 1 AU from the star. This “1-m barrier” has long been a challenge for planetary scientists, and raises the question: How do planet-sized bodies like the Earth form at all?

The first time I asked myself this question, I was a novice to astrophysics, finishing my degree at Pisa University. It seemed extraordinary to me that the great physicist Albert Einstein could have formulated his grand theory of the universe, General

Relativity, decades before we had a clue about how our Earth formed. This is ultimately due to the fact that planetary formation is messy; it spans a wide range of spatial and temporal scales, and is modulated by the interplay of a variety of physical processes. Simply put, while the expansion of the universe under certain assumptions can be rationalized with a single equation, there is no single equation that describes the formation of the Earth. So it is no surprise that, even though the idea of a nebular origin of the Solar System was first proposed by the Prussian philosopher Emmanuel Kant in 1755, it took more than 200 years to make it a viable scenario. Our understanding of the Solar System has made giant leaps over the past decades, thanks to the availability of refined computer models as well as laboratory work, which have helped us to overcome the problems associated with understanding the growth of solid particles.

The missing piece to the puzzle of how pebbles of just under a meter in diameter can continue to grow turned out to be down to a subtle effect. As gas and pebbles orbit the central star in unison, they perturb each other. The perturbation is an imperceptible one that arises from the fact that gas and dust revolve around the central star at slightly different velocities. In essence, dust grains experience slight but persistent headwinds that push them to accumulate in denser regions, called clumps. Under the right conditions, clumps form rapidly over a timescale of a few orbital revolutions around the Sun, or a few years at 1 AU.

These dense clumps are self-sustaining because they warp the distribution of gas in the disk, which further stimulates the piling up of more particles. Eventually, these overdense regions tend to attract more material onto them gravitationally. Clumps grow in size by accreting streams of nearby gas and pebbles until their gravity is high enough to trigger a rapid collapse. This inward collapse of the clumps quickly produces myriad small planets

6 · born out of fire and chaos

called “planetesimals” scattered around the disk. According to computer simulations, the size of these planetesimals could range from 10 to 1000 km or more. So, with a giant leap, pebbles gain an additional four to six orders of magnitude in diameter, overcoming the forces acting against their growth.

The appearance in the disk of sizable solid objects is a game changer. They are localized centers of gravitational attraction and further grow in size by deflecting and accreting smaller pebbles passing by. There are uncertainties about this process, and not all scientists agree,2 but numerical models predict that Marssized planets can be produced over a timescale of a few million years. So in a mere tenth of a percent of Solar System evolution, planetary embryos were popping out from a gaseous and dusty protoplanetary disk.

Up until now, the formation of planetesimals has been inextric ably linked to the presence of gas. The gas has a calming role in the earliest evolution. As planetesimals swirl through gas, they experience air drag, which helps to maintain them on nearly circular orbits. Nearby objects can occasionally cross paths and collide at a relatively low speed, because of their similar orbits. This is equivalent to traveling on a busy highway at a constant speed that is only a few kilometers per hour higher than that of a leading car. In a collision, what matters is not the absolute speed of the cars but their relative speed. So grains that collide gently are more likely to stick together and grow in size.

The gas doesn’t remain stable forever. In fact, astronomers have observed that protoplanetary disks around nearby stars tend to vanish on average a few million years after the ignition of the central star, and 10 million years later, most stars have no disks. The process responsible for the gas removal isn’t totally clear. Gas may be absorbed by the central star, as when dust spirals inward toward the Sun, it may be blown away by stellar winds,

born out of fire and chaos · 7 or it may evaporate into space. Without the stabilizing effect of air drag, planetesimals become erratic and start perturbing each other’s orbits. This marks the beginning of a new phase of evolution in which orbits cross at an angle and collisions become more violent. Think of two cars colliding at a crossroad. The final assemblage of planets is characterized by full-blown, planetaryscale collisions, the most energetic of which could even shatter some planetesimals into many small pieces. If, though, a planetesimal has managed to achieve a diameter in excess of 1000 km or so, then it is so tightly gravitationally bound that it is unlikely to be completely torn apart by a collision. To the contrary, like large fish in a pond feasting on smaller fish, the few largest planetary embryos in the population grow progressively faster by gravitationally attracting and sweeping up the smaller planetesimals. During this gas-free stage of growth, planetesimals develop eccentric orbits that cross larger portions of space. Now, the “feeding zones” of the planetary embryos become more dispersed, and the accretion slows down. Astronomers think that this process took some 50–80 million years to be completed for the Earth. During this time, the Earth grew from a mere 6,000 km in diameter (about the size of Mars today) to its final 12,742 km.

The accretion of the Earth, and presumably that of other rocky planets, was, then, no smooth, deterministic process. It proceeded in discrete steps, with each collision having specific consequences. The growth in size described above could, very crudely, be imagined to have been due to collisions of planetesimals 1000 km wide. It takes approximately 3000 such objects to make the Earth, or a collision every 25,000 years on average. Similarly, it would have taken about ten Mars-sized bodies to form the Earth, or a collision every few million years on average. Each collision added raw building materials to the Earth, and in doing so transformed it into a new and different world, which

8 · born out of fire and chaos then provides the substrate for the next one to come. While the Earth was probably largely molten throughout this phase, the size and energy of the collisions were random, as were the properties of the fully assembled planet.

The details in the accretion of the Earth are particularly important to understand the origin of its oceans. If the Earth grew from a multitude of small planetesimals (say less than 1000 km in diameter) then their internal heat could have driven volatiles, including water, to space before having a chance of being retained by the fully grown Earth. Alternatively, if pebbles condensed directly to form larger Mars-sized embryos, then their water would have been more easily retained and passed on to the Earth in collisions. We shall return to this in Chapter 4.

In conclusion, the current paradigm of planetary formation requires collisions, and lots of them, to form large rocky planets. This is one of the reasons why Earth’s formation was messy, as noted at the beginning of this chapter. Let’s now take a broader look at the Solar System through the lens of collisions and their associated processes.

A telltale sign of the random evolution of the planets is the very different properties of the so-called terrestrial planets—Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. One of the most puzzling questions concerns why Venus, considered Earth’s sister planet because of its similar size and distance from the Sun, is so different from our own. We can reasonably assume that both planets accreted from the same building blocks, given their similar distance from the Sun. Venus’s diameter is only 6 percent smaller than that of Earth, also indicating a similar growth history. If this is correct, then we can conclude that they shared a similar start and similar overall properties. And yet, something must have happened during their evolution to put them on very different pathways, resulting in a dry Venus with a thick poisonous atmosphere dominated

born out of fire and chaos · 9 by carbon dioxide and a surface scorched by temperatures that exceed 400 °C. Scientists have proposed a number of explanations to account for Venus’s un-Earthlike atmosphere. According to a popular theory, what we see today could have resulted from tiny differences that accumulated over the eons.

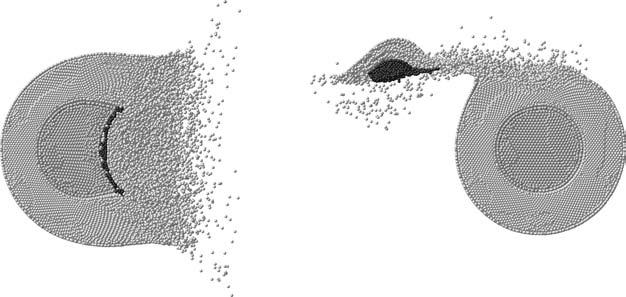

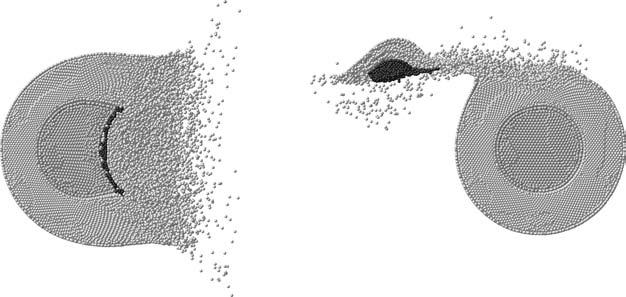

Consider now the fate of light elements, such as hydrogen, in the top layer of the atmosphere. The speed of atoms depends on the ambient pressure and temperature, and since Venus is slightly smaller and closer to the Sun than the Earth, everything else being the same, hydrogen atoms on Venus can be expected to move faster, on average. A fraction of the atoms could reach velocities that enable them to overcome the gravitational attraction of the planet (slightly less on Venus than Earth) and escape into space. Over time, this could cause an impoverishment of hydrogen and other light elements. Hydrogen is a key constituent of water, so losing hydrogen effectively means losing water. Planetary scientists think that these sorts of slow processes may be responsible for the differences between Venus and the Earth. But there are other possibilities too. We have seen how, in its final stages, the accretion of a planet would be characterized by violent, massive collisions. This makes the early evolution of a planet unforeseeable. Even if two planets accrete from the same population of objects, with identical timescales, their end states may depend on the nature of a few last big collisions. The velocity, and therefore the energy, of these collisions could be different. And the geometry of the collisions also has an important effect on the final thermal state of a planet. In a grazing collision, the projectile is torn apart and shredded into a spray of fragments which end up largely falling back on the entire planet’s surface, with devastating effects. At the other extreme, in a headon collision, the projectile penetrates deeper into the planet, but the effects are more localized (Figure 1, Plate 2). The nature of

Figure 1. Simulations showing the effect of large collisions on Earth. The illustrations show in cross-section the impact of a 4000-km wide planetesimal striking the Earth with a velocity of 19 km/s. The ensuing disruption strongly depends on the impact direction, whether a head-on collision (left), or a grazing collision (right; 60º from the normal at the impact point). The numerical code uses spherical particles to simulate shock and disruption of the Earth and the projectile. The dark gray particles indicate the strongly deformed metallic core of a projectile. The inner darker-gray circle within the Earth represents its metallic core.

the particular large, random collisions experienced by Venus in its last phases of accretion may have played a role in why its thick atmosphere differs so much from that of the Earth.

A planet’s atmosphere forms a thin envelope that separates it from open space. This interface is susceptible to external processes, such as interplanetary collisions, but a full understanding of an atmosphere also requires knowledge of the planet’s internal evolution. Alas, we don’t know much about the interior of Venus, but based on limited imagery of the surface, we believe that it is volcanically active, perhaps with a surface just a few hundred million years old. And yet, there is no obvious signature of recycling of the crust, as plate tectonics achieves on Earth. The

born out of fire and chaos · 11 question of the age of the surface of Venus is key to this story. Scientists infer that the surface is young because of the low number of impact craters. While this is a very imprecise technique, it does give us a rough idea of age when no direct access to surface rocks is possible. We will come back to this point in detail in Chapter 2. One possible explanation for a relatively young surface is that Venus is internally very active, with frequent and massive lava eruptions that spread out and blanket the surface, wiping it clean.

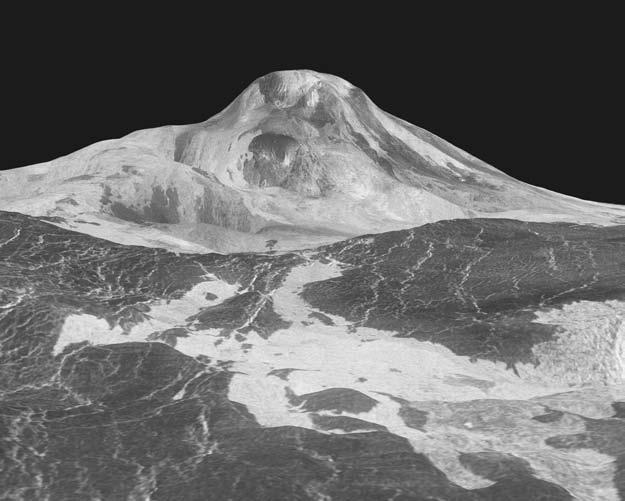

Several Soviet Venera spacecraft landed on its surface in the 1970s and 1980s, and lasted long enough to beam back to Earth a few pictures. The images from the Venera landers look a lot like the desolated landscape that Frodo and Sam traversed when headed for Mount Doom in the concluding part of Peter Jackson’s film series of Tolkien’s classic work, The Lord of the Rings. The comparison is even more pertinent as the surface of Venus, observed from orbit thanks to radar capable of penetrating the thick atmosphere, has been found to be studded with more than a thousand volcanoes, the largest of which, Maat Mons, is about 8 km in height (Figure 2). Associated with these eruptions would be the release of copious amounts of sulfur and carbon, which may contribute to Venus’s poisonous atmosphere of carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid.

We have discussed how collisions could provide a reason for Venus being different from Earth from the get-go, but we cannot rule out the possibility that they started out as similar planets and then diverged over the eons. This has fascinating implications. The early Earth became habitable soon after its formation. We can imagine a Venus that was also water rich in its early days, perhaps as is inferred for Mars, but lost its water with the eruptions and lava outpourings from the endless internal churning of

Figure 2. Maat Mons, Venus. The flank of Venus’s highest volcano is draped with overlapping lava flows extending across the surrounding plains for hundreds of kilometers. Terrain elevation reconstructed using radar data from the NASA Magellan mission.

the planet. Perhaps Venus even hosted life for a brief time before becoming inhospitable.

Venus also differs from Earth because it lacks a moon. Most scientists believe that our Moon formed as a result of a massive collision. The body that collided with the proto-Earth has been named Theia, after the Greek goddess who gave birth to the Moon. Upon collision, Theia and proto-Earth would have partially merged, and produced a disk of gas and debris orbiting a fully molten nascent Earth (Plate 3). It is from this disk that the Moon arose, similarly to the way in which the planets formed in the protoplanetary disk. This theory finds support in the Moon’s

born out of fire and chaos · 13 rock chemistry. Scientists use elements such as oxygen and magnesium and the relative proportions of their different isotopes as fingerprints to assess the makeup of planetary objects. This is because certain elements retain a distinct pattern even as the rocks in which they are found are profoundly transformed and incorporated into the final object. While the bulk composition and structure of the Moon is certainly very different from that of Earth, the detailed balance of isotopes of a large array of elements, most notably oxygen, suggests a common origin. Isotopes that result from radioactive decay, known as radiogenic isotopes, also provide a constraint on the timing of this massive collision, which took place some 50–80 million years into the evolution of the Solar System. We will return to this point in Chapter 2. How might the Earth have evolved without that last bit of cosmic havoc that resulted in the formation of the Moon? This is a fundamental question, and yet one that we cannot fully answer. While there is still considerable debate about the details of the Moon- forming collision, models suggest that Theia may have ranged from about half to five times the mass of Mars.3 A fraction of Theia merged with the Earth, adding anything between a few percent to 50 percent of the Earth’s final mass. Intriguingly, moon-less Venus has 20 percent less mass than the Earth. One could speculate that Venus did not go through the equivalent of Earth’s final most violent step in accretion. So perhaps Venus shows us how the Earth could have looked if it had missed that collision with Theia.

How can we discover whether early collisions had a role in shaping Venus’s inhospitable nature? If the surface of Venus is truly as young as we think, then the signature of the earliest collisions and other processes would be long gone. But as we shall see later, collisions may leave behind subtle geochemical signatures