Introduction

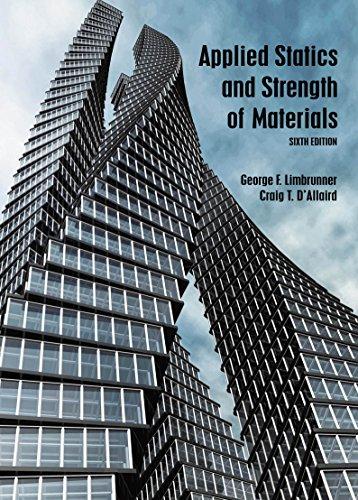

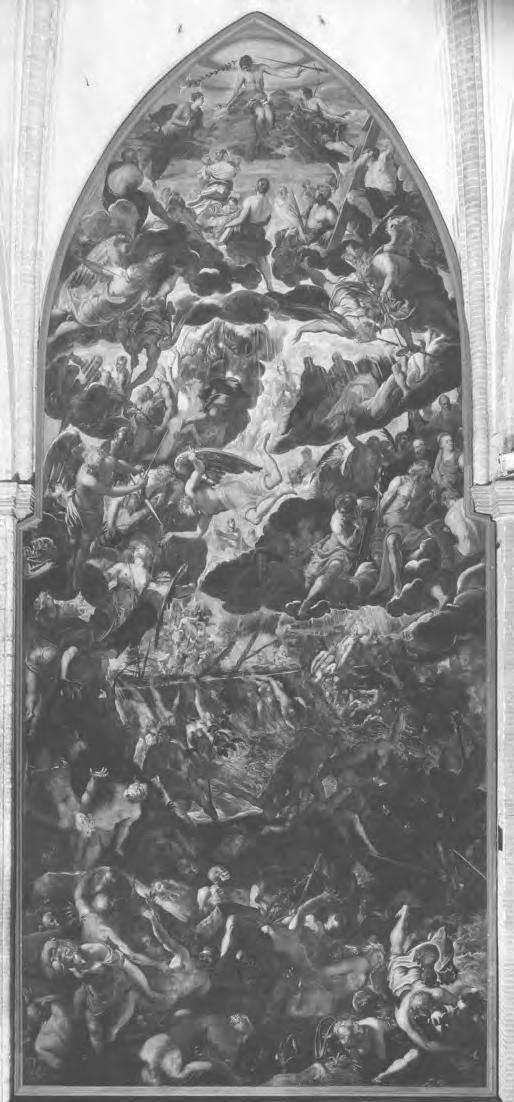

TheVenetianChurchoftheMadonnaoftheGarden(the Madonnadell’Orto)lies atthenorthernedgeofthedistrictofCannaregio,closetowherethebuiltenvironmentmeetsthelagoon.Amagnificentpaintingdominatesthewallofthechurch’ s chancel.JacopoTintoretto’ s LastJudgement (c.1562)isadistinctive,Venetian variationonacommonCatholic-Reformationtheme[ImageI.1].Here,the momentofjudgementarrivesasacascading flood.Thewaterssweepaway thelivingandthedead.Angelsliftthefaithfulfromthewaves.Divinetemporality andthedynamicsofsalvationarerealizedthroughtheforcesofthenaturalworld.

Thisisapowerfulimageforacitywhichwasrenownedforitsdistinctive construction ‘inthemiddleofthesea’.¹Venice’slocationhasattractedtheaweand affectionofobserversforcenturiesbutitalsoinflictsaheavyphysicaltollonthecity’ s infrastructure,fromtheintensestrainof floodstotheincrementalchangeswrought byhumidityandthemovementofthetides.²IntheperiodinwhichTintoretto’ s paintingwascreated,theconditionofthenaturalenvironmentwasimbuedwith additionalforceandmeaning.³Theenvironmentwasbelievedtoreflectandshape moralconditionsandconcerns.WhatthetopographicalsingularityofVenicemade evidentwastrueofcitiesacrosstheearlymodernworld:inordertounderstandthe strengthsandchallengesofaplace political,economic,religious,socialand medical itwasessentialtorecognizetheparticularitiesoftheenvironment.⁴

¹JohnEvelyncitedinJillStewardandAlexanderCowan, ‘Introduction’ in Thecityandthesenses: urbanculturesince1500 (London:Routledge,2016),p.4.

²ElizabethCrouzetPavan’ s ‘Sopraleacquesalse’:Espacesurbains,pouvoiretsociétéàVeniseàla fin duMoyenAge (2vols,Rome:IstitutostoricoitalianoperilMedioEvo,1992)consideredthewaysin whichtheenvironmentshapedspaceandformsofgovernmentinmedievalVenice.ErmannoOrlando’ s nuancedstudyofthelagoonfocuseduponpoliticaladministrationratherthanhealthandtheenvironment: AltreVenezie:IldogadovenezianoneisecoliXIIIeXIV(giurisdizione,territorio,giustiziae amministrazione)(Venice:Istitutovenetodiscienze,lettereedarti,2008).Seealsothe Antichiscrittori volumesandSalvatoreCiriacono, ‘Scrittorid’idraulicaepoliticadelleacque’ inGirolamoArnaldiand ManlioPastoreStocchi(eds), Storiadellaculturaveneta.DalprimoQuattrocentoalConciliodiTrento vol 3/II(Vicenza:N.Pozza,1980),pp.500–5.AnimportantworkontheVenetianenvironmentduringthe RenaissanceisKarlAppuhn, Aforestonthesea:environmentalexpertiseinRenaissanceVenice (Baltimore MA:JohnsHopkinsUniversityPress,2009).

³ClaireWeeda, ‘Cleanliness,civilityandthecityinmedievalidealsandscripts’ inCaroleRawcliffe andClaireWeeda(eds), PolicingtheenvironmentinpremodernEurope (Amsterdam:Amsterdam UniversityPress,2019),pp.39–68.

⁴ Asyet,AlexandraWalsham’sexplorationoftheinfluentialrelationshipbetweentheReformation andthelandscapeinBritainhasnotbeenmatchedfortheCatholicReformation.AlexandraWalsham, TheReformationofthelandscape:religion,identity,andmemoryinearlymodernBritainandIreland (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2011).

CleaningUpRenaissanceItaly:EnvironmentalIdealsandUrbanPracticeinGenoaandVenice.JaneL.StevensCrawshaw, OxfordUniversityPress.©JaneL.StevensCrawshaw2023.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198867432.003.0001

ImageI.1 JacopoTintoretto, TheLastJudgement (1562–64).Venice,Churchofthe Madonnadell’Orto.Oiloncanvas.cm1450 590.©2020.Cameraphoto/Scala, FlorenceandreproducedwithkindpermissionoftheUfficioBeniCulturalidel PatriarcatodiVenezia[Prot12.22.2702].

Theligaturesthatboundpeopletotheirbroadersettingsduringthepremodern periodwerethecorrespondencesbetweentheconstituentpartsofthehuman body(thefourhumours)andthoseofthenaturalworld(thefourelements).⁵ TheseconnectionslayattheheartoftheHippocraticcorpusofmedicalideasand hadbeeninfusedwithChristiantheology.⁶ Itwaswidelybelievedthatenvironmentscouldalterthenatureofthebody,shapingtemperaments,behavioursand health.⁷ Seafaringmen,forexample,weresaidtobe ‘liketheElementtheybelong to,muchgiventoloudnessandroaring’ . ⁸ Theseassociationspromptedgovernmentactivitiestomanageurbanspaceandnaturalenvironments;crucially,they endowedsuchworkwithsocialandsymbolicsignificance.Interventionssuchas thecleaningofstreets,thedredgingofportsordiversionofrivers,then,wereoften intendedtohavesocialorreligious,aswellasmedicalandenvironmental,effects.⁹ Itisthesemeasuresandtheirmeaningswhichlieattheheartofthisbook,which exploresthesocialandculturalhistoryofenvironmentalmanagementintwo Renaissanceports:GenoaandVenice.¹⁰

Therelevanceofthissubjectmatterisilluminatedinasecondpaintingin Venice’schurchofthe Madonnadell’Orto:Tintoretto’ s PresentationoftheVirgin attheTemple. AstheyoungVirginMary embodyingpurity ascendsornate stepstowardstheHighPriest,herpathislinedbypeople:youngandold,richand poor,maleandfemale.Inthevibrant,cosmopolitanportsofGenoaandVenice,

⁵ SandraCavalloandTessaStorey(eds), Conservinghealthinearlymodernculture:bodiesand environmentsinItalyandEngland (Manchester:ManchesterUniversityPress,2017)considersthenonnaturalsinabroadergeographicalandchronologicalcontext.

⁶ SimonaCohenhasremindedusthat ‘correspondencesestablishedbetweencategoriesofTime (days,seasons,months,ages),space(cardinalpoints,signsofthezodiacandplanetsascelestialand temporalimages),andmatter(elements,humours)wereconceivedasevidenceofthedivine’ in ‘The earlyRenaissancepersonificationofTimeandchangingconceptsoftemporality’ , RenaissanceStudies 14:3(2000),306–7.Thecorrespondencesthatconnectedthehumanbody(themicrocosm)withthe macrocosmoftheenvironmentorcreatedworldalsoincludedassociationswiththebodypolitic.Justas therewerefourhumoursandelements,therewerefourseasonsandtimesoftheday,fourpartsofthe knownworld(Africa,theAmericas,Asia,andEurope)aswellasfourcardinalvirtuesinPlato’sRepublic (wisdom,courage,moderation,andjustice).Therewerefurthercorrespondencesbetweenthethree principalorgansofthebody,threeagesofman,andtheChristianTrinityaswellassevenagesofman andsevenstagesinworldhistory.

⁷ NancyG.Siraisi, MedievalandRenaissancemedicine:anintroductiontoknowledgeandpractice (ChicagoIL:UniversityofChicagoPress,1990).

⁸ MandevillecitedinLottevandePol, Theburgherandthewhore:prostitutioninearlymodern Amsterdam (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2011),p.157.

⁹ Theseconnectionsinacolonialcontextseethebriefmentionofthedrainageprojectof desagüe in MexicoCitydiscussedbyDanielNemser, ‘Triangulatingblackness:MexicoCity1612’ , MexicanStudies/ EstudiosMexicanos 33:3(2017),349.

¹

⁰ Similarcorrespondencescouldbefruitfullyexploredinrelationtotheeconomy.Regulationof marketplaceswasoftendrivenbypublichealthconsiderations.SeeDennisRomano, Marketsand marketplacesinmedievalItalyc.1100–1440 (NewHavenandLondon:YaleUniversityPress,2015).For valuableworkontheimpactoftheconceptofthemarketplaceonexpressionsofspiritualityand salvationseethestudiesbyGiacomoTodeschiniincluding IlPrezzodellasalvezza:lessicimedievalidel pensieroeconomico (Rome:NuovaItaliascientifica,1994).CarolineBruzeliusreferstotheimageryof Christasagoodmerchantin Preaching,buildingandburying:friarsinthemedievalcity (NewHaven andLondon:YaleUniversityPress,2014),p.127.

thestoriesofenvironmentalmanagementinvolveabroadcross-sectionof Renaissancesociety:fromcourtesanstostreetfoodsellersandarchitectsto canaldiggers.Althoughthesourcesonwhichthisstudyrestsarelargelyarchival, producedbyaminisculeproportionofthemalepopulation,theyrevealsomething oftheidealsandlivedexperiencesofafarbroadersocialcross-sectioninrelation tohealthandtheenvironment.Inhisreflectiononculturalhistoryaspolyphonic history,PeterBurkeportrayedthehistoryofcleanlinessasa ‘meetingpoint’ betweenstudiesofcodes,cultures,metaphorsandidentities,alongwiththe physicalobjectsofbodiesandenvironments.¹¹Itisthusexploredinthisbookas apointofintersectionbetweenideas,behavioursandregulation.

Alastlookatthechurchofthe Madonnadell’Orto revealsa finalidearelevant tothemanagementoftheenvironmentandhealth:thedynamicintersection betweentheunitsofthelocalityandthestate.¹²Manyoftheimagesonshowin thechurchdepictedorwereproducedbyinhabitantsoftheparish,including membersoftheTintorettofamilyandParisBordone.¹³Theseremainalongside representationsofimportantcivic figures,aswellasVenetiansaints,theportraits ofwhomwerecommissionedin1622bythecity’sPatriarchGiovanniTiepolo.

Thisinterplaybetweenthecircumstancesofthelocalityandtheintentionsof centralizinginstitutions(includingboththestateandtheCatholicChurch)isalso evidentifwemove165mileswest,toasecondchurchdedicatedtoOurLadyof theGarden(NostraSignoradell’Orto)intheseaportofChiavariontheLigurian coast.Here,intheearlydecadesoftheseventeenthcentury,acultdeveloped amongstthepoorinhabitantsofasuburb.Itgainedsuchmomentumthatthe ecclesiasticalandpoliticalauthoritieseventuallyauthorizedandformalizedthe devotions.¹⁴ Itshistoryremindsusthatlayersofauthorityandidentitycoexisted inRenaissanceterritories.Theconcernsandprioritiesofpeopleatlocal,civicand territoriallevelsometimescompeted.Notionsoforder,pietyorwellbeingcouldas readilyresultintensionascollaborativeenterprise.Communitiesalsousedthe structuresofenvironmentalmanagement,amongstothers,toresolvethechallengesofurbanlife bothsocialandphysical aswellasbeingsubjecttothe oversightofthesame.

¹¹PeterBurke, ‘Culturalhistoryaspolyphonichistory’ , ARBORCiencia,PensamientoyCultura CLXXXVI743(2010),479–86.SeealsotheworkofMarkJennerincluding ‘Doctoringtheenvironment withoutdoctors?PubliccleanlinessandenvironmentalgovernanceinearlymodernLondon’ , Storia urbana 112(2006),17–37.

¹²OnRenaissanceItalianstatesandkeyhistoriographicaldebatesanddevelopmentsseethe introductiontoAndreaGamberiniandIsabellaLazzarini, TheItalianRenaissanceState (Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,2012).MichaelJ.Braddick, StateformationinearlymodernEngland c.1550–1700 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2000)providesavaluableseriesofperspectives onstateformationofthisperiod.ForthevitalityofthelocalityinVeniceseetheseriesofvolumes coordinatedbyGianmarioGuidarellientitled ‘ChurchesofVenice.Newresearchperspectives’

¹³TomNichols, Tintoretto:traditionandidentity (London:Reaktion,2015).

¹⁴ JaneGarnettandGervaseRosser, Spectacularmiracles:transformingimagesinItalyfromthe Renaissancetothepresent (London:Reaktion,2013),p.81.

Thisbookbridgesthehistoriesofurbanandnaturalspace,studyingcitiesin theirwidercontextsandhighlightingtheimportanceoftheenvironmentforthe wellbeingofearlymodernsociety.¹⁵ Theenvironmentalidealsreferredtointhe titleincludethosewhichrelatetobothbuiltandnaturalsettings.Thereferenceto urbanpracticesisnotintendedtosuggestthatthespatialunitofstudyhereis limitedbywallsorothercivicboundaries.Instead,thestudyisdirectedbywhat mightbetermedanurbangazeanddilatesuponthoseenvironmentalissuesand concernswhichwerebelievedtobepertinenttothehealthandwellbeingofthe city.Thedynamicsofidealandpracticeincentralsquaresandprominentstreets areconsideredalongsidespaceswhichweremorehiddenfromview:dark,narrow alleywaysandcapacioussubterraneandrains.¹⁶ Theseplacesformedavitalpartof theinfrastructureofhealth,whichwassocentraltotheexperienceoflifeinthe Renaissancecity,andthroughwhichurbancentreswereconnectedwiththeir widersettings.¹⁷

Thisperspectivehighlightsthenotableimportanceofthelocalityandregionin earlymodernenvironmentalthinking,evenatatimewhenHistorywasbeing writtenandrewritteninthecontextofexpandingunderstandingsoftheworld.¹⁸

InGenoaandVeniceexplanationsofenvironmentalchangesrarelyemployeda frameofreferenceasbroadasanoceanorcontinent.¹⁹ Instead,environmental problemsandsolutionsweresituatedinamorelimitedgeographicalarea.²⁰ The

¹⁵ Foradiscussiononthehistoriographyofurbanandenvironmentalhistoryoftheearlymodern periodseeMartinKnoll, ‘From “urbangap” tosocialmetabolism:theearlymoderncityin environmentalhistoryresearch’ inMartinKnollandReinholdReith(eds), Anenvironmentalhistory oftheearlymodernperiod:experimentsandperspectives (Zurich:Lit,2014),pp.45–50.Useful reflectionsonmethodologyandapproacharealsomadeinGeorgStöger, ‘Environmentalperspectives onpre-modernEuropeancities difficultiesandpossibilities’ inMartinKnollandReinholdReith (eds), Anenvironmentalhistory,pp.51–5.ExcellentintroductionsincludeSverkerSörlinandPaul Warde(eds), Nature’send:historyandtheenvironment (Basingstoke:PalgraveMacmillan,2009)and PaulStock(ed.), TheusesofspaceinearlymodernHistory (NewYorkNY:PalgraveMacmillan,2015). Ontheconceptof ‘ space ’ forhistoriansseePeterArnade,MarthaHowell,andWalterSimons, ‘Fertile spaces:theproductivityofurbanspaceinnorthernEurope’ , JournalofInterdisciplinaryHistory 32 (2002),515–28.

¹

⁶ FabrizioNevola, StreetlifeinRenaissanceItaly (NewHavenandLondon:YaleUniversityPress, 2020)hasexploredthisrelationshipbetweenpeopleandplaceinthebuiltenvironment.

¹

⁷ Thisstudyarguesforabroaddefinitionof ‘healthinfrastructure’ andnotestheongoingdebatein acontemporarycontextaboutan ‘artificialdividebetweenphysicalandhumaninfrastructure’ inBhav Jain,SimarS.Bajaj,andFatimaCodyStanford, ‘AllInfrastructureIsHealthInfrastructure’ , American JournalofPublicHealth 112:1(2022),24–6.

¹

⁸ GiuseppeMarcocci, Theglobeonpaper:writinghistoriesoftheworldinRenaissanceEuropeand theAmericas (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2020).LydiaBarnett, Afterthe flood:imaginingthe globalenvironmentinearlymodernEurope (BaltimoreMA:JohnsHopkinsUniversityPress,2019).

¹

⁹ CornellFleischer, ‘AMediterraneanapocalypse:propheciesofempireinthe fifteenthand sixteenthcenturies’ , JournaloftheEconomicandSocialHistoryoftheOrient 61:1–2,18–90onthe interestingconnectionsbetweenMillenarianthoughtacrosstheMediterranean.AlisonBashford, DavidArmitage,andSujitSivasundaram(eds), Oceanichistories (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press,2018).

²⁰ Futureresearchwouldbenefitfromanexplorationofthoseenvironmentalfeatures,suchasrivers whichtraversedpoliticalboundariesinordertoexploreissuesoflocalismandregionalismingreater depth.

themesexploredinthisbook,therefore,requireaspecificformof ‘connected history’,whichisdistinctlysituationalandsocial.²¹Knowledgeabouthealthandthe environmentcombinedsocial,religiousandethnicstereotypesandprejudices withmedicaltheoryandempiricalobservation.Thisargumentbuildsoninsights fromanthropology(particularlythewidely-influentialworkofMaryDouglas [1921–2007]).²²Hermethodologyforaligninghumanuniversalsandculturalphenomenahaspavedthewayforcomparativeapproachestohealthandwellbeing.²³

Whenwritersoftheperiodreferredtopublichealth(as salute ‘ commune ’ , ‘pubblica’ or ‘universale’),theyunderstoodthistoencompassabroad,interconnectedrangeofideasandinitiativesrelatingtobehaviour,moralityandsalubrity, includingbothpreventativeandcurativepractices.²⁴ Thislanguagewasfrequently invokedinVenice,alongsidethatof ‘comfort’ , ‘utility’ and ‘benefit’ tojustify environmentalinterventions.InGenoa,however,strikinglysimilarmeasures werejustifiedwithreferenceto ‘publiccomfort’ (commodopublico )andthe needtoprotectthecity’sport.Theconceptofpublichealthwasarticulatedless readilytojustifygovernmentinterventionsandagreaterrolewasacknowledged forindividuals,particularlymembersoftheelite,insparkingandsustaining activities.Hereweseethe ‘informalworld[ofItalianRenaissancepolitics which]facedtheinstitutions,formingwiththemthe unicum ofpolitics’.²⁵ The comparisonbetweenthesetwocity-stateshelpstoshiftourfocusawayfromthe dominanceofnotions(orlonghistories)ofpublichealthinrecentstudiesto recognizethateffortstopreservethehealthofcitiesmightnotrequirethefrequent deploymentofthistermoritsassociatedbureaucraticstructures(represented soofteninaRenaissanceItaliancontextbygovernmentHealthOffices).²⁶

²¹ForanimportantstudyofconnectedhistoryseeSanjaySubrahmanyam, ‘Connectedhistories: notestowardsareconfigurationofearlymodernEurasia’ , ModernAsianStudies 31:3(1997),735–62.

²²MaryDouglas, Purityanddanger:ananalysisofconceptsofpollutionandtaboo (London: Routledge,2002).

²³ForastimulatingdiscussionofDouglas’sideasandtheirimpactseeMarkBradley, ‘Approachesto pollutionandpropriety’ inMarkBradley(ed.), Rome,pollutionandpropriety:dirt,diseaseandhygiene intheEternalCityfromantiquitytomodernity (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2012), pp.11–40.

²⁴ SeeSandraCavalloandTessaStorey, HealthylivinginlateRenaissanceItaly (Oxford:Oxford UniversityPress,2014);RobertaMucciarelli, ‘Igiene,saluteepubblicadecoronelMedioevo’ inRoberta Mucciarelli,LauraVigni,andDonatellaFabbri(eds), Vergognosaimmunditia:igienepubblicaeprivata aSienadalmedioevoall’etàcontemporanea (Siena:NIE,2000);JohnHenderson, TheRenaissance hospital:healingthebodyandhealingthesoul (NewHavenandLondon:YaleUniversityPress,2006); LauraMcGough, Gender,sexualityandsyphilisinearlymodernVenice:thediseasethatcametostay (Basingstoke:PalgraveMacmillan,2011);SamuelK.CohnJr., Culturesofplague:medicalthinkingat theendoftheRenaissance (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2010)andGauvinBailey,PamelaJones, FrancoMormando,andThomasWorcester(eds), Hopeandhealing:paintinginItalyinatimeof plague1500–1800 (WorcesterMA:WorcesterArtMuseum,2005).

²⁵ AndreaGamberiniandIsabellaLazzarini(eds), TheItalianRenaissanceState,p.4.

²⁶ Traditionalaccounts,suchastheexcellentworkofCarloCipolla,recognizedtheearlydevelopmentofItalianhealthboardsandtheirbroadjurisdictionalresponsibilities.Forexample,CarloCipolla, PublichealthandthemedicalprofessionintheRenaissance (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1976).

Alternativeconceptsmightalsofacilitateeffortstoinstituteurbancleanlinessand collectivewellbeing.WhatemergesfromthisstudyofGenoaandVeniceisthe emphasisplacedonenvironmentalidealstojustifyurbanpracticesinrelationto health.

Anemphasisontheconditionofplaceshighlightsthehistorically-contingent natureoftheagencyofspace.Aspartofthe ‘spatialturn’ inhistoricalwriting, scholarshaverespondedtotheworkofMichelDeCerteauandHenriLefebvre, amongstothers,toexplorethedynamicsofspaceincitiesandonstreets.²⁷ Asyet, thesestudieshaveyettobealignedfullywiththemechanismsbywhichplacewas believedtoexertagencyovertime.²⁸ Formanycenturies,andacrossmany cultures,thisimpactwasexplainedusingthetenetsoftheHippocraticCorpus.²⁹ Inthisenduringframework,peopleweredirectlyshapedby(and,inturn,altered) theirurbanandnaturalenvironments. ‘Private’ issuesofbehaviourandcleanliness,therefore,wereofpublicsignificance.Afailuretofollowhealthmeasureswas morethananinconvenienceorannoyance:thenatureofneighboursandneighbourhoodscouldhavephysicalandmoralconsequences.³⁰

Thefocushereonthe fifteenthandsixteenthcenturiesisnotintendedto suggestthatthesecorrespondences,implicationsorpracticeswerenewinthe Renaissance.³¹Thereissignificantcontinuitytobeemphasizedintheenvironmentalandmedicalpracticesundertakenbetweentheperiodswhichprecedeand followtheoneunderconsiderationhere.³²Indeed,itishardlysurprisingto find

²⁷ BeatKüminandCornelieUsborne, ‘Athomeandintheworkplace:ahistoricalintroductionto the “spatialturn”’ , HistoryandTheory 52(2013),305–18.FortheearlymodernperiodseeMarcBoone andMarthaHowell(eds), ThepowerofspaceinlatemedievalandearlymodernEurope:thecitiesof Italy,NorthernFranceandtheLowCountries (Turnhout:Brepols,2013)andGeorgiaClarkeand FabrizioNevola(eds), ‘TheexperienceofthestreetinearlymodernItaly’ , ITattiStudiesintheItalian Renaissance 16:1/2(2013).

²

⁸ Theseassociationshaveattractedlessattentionfromearlymodernsocialandculturalhistorians thanscholarsofEnglishliteratureormedicalhistory.ExceptionsincludeSaraMigliettiandJohn Morgan(eds), Governingtheenvironmentintheearlymodernworld:theoryandpractice (London: Routledge,2017)andHannahNewton, ‘“Natureconcoctsandexpels”:theagentsandprocessesof recoveryfromdiseaseinearlymodernEngland’ , SocialHistoryofMedicine 28:3(2015),465–86.

²⁹ CharlesEstienneexplainedvariationsofsoilwithreferencetohumouralcombinations clays werecoldandmoist,sandshotanddryandallothersweremix.SeePaulWarde, Theinventionof sustainability:natureanddestinyc.1500–1870 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2018),p.45. FortherevivalofHippocraticideasinthesixteenthcenturyseeDavidCantor(ed.), Reinventing Hippocrates (Aldershot:Ashgate,2002).

³

⁰ SeeBarbaraRouse, ‘Nuisanceneighboursandpersistentpolluters:theurbancodeofbehaviourin latemedievalLondon’ inAndrewBrownandJanDumoly(eds), Medievalurbanculture (Turnhout: Brepols,2007),75–92;BronachC.KaneandSimonSandall, Theexperienceofneighbourhoodin medievalandearlymodernEurope (London:Routledge,2022);PaulaHohtiErichsen, Artisans, objects,andeverydaylifeinRenaissanceItaly:thematerialcultureofthemiddlingclass (Amsterdam: AmsterdamUniversityPress,2020),pp.70–1.

³¹KathleenDavis, Periodizationandsovereignty:howideasoffeudalismandsecularizationgovern thepoliticsoftime (PhiladelphiaPA:UniversityofPennsylvaniaPress,2008).

³²FortheprecedingperiodseeGuyGeltner, Theroadstohealth:infrastructureandurbanwellbeing inmedievalItaly (PhiladelphiaPA:UniversityofPennsylvaniaPress,2019)and ‘Healthscapinga medievalcity:Lucca’ s curiaviarum andthefutureofpublichealthhistory’ , UrbanHistory 40:3(2013), 395–415;CaroleRawcliffe, Urbanbodies:communalhealthinlatemedievalEnglishtownsandcities

repetitioninmeasures,giventhatcleaningisoftenongoingandrepetitivework. Whilstacknowledgingimportantcontinuities,archivalmaterialrevealsfour thingswhichwerespecificaboutthemanagementofhealthandtheenvironment duringtheRenaissance.First,thisworkwasundertakeninacontextofconsiderableepidemiologicalandenvironmentalchange.Europeenteredwhathasbeen termedtheLittleIceAgeandscholarsofepidemicdiseasehaverecognizedthat outbreaksofplague(andthenewdiseaseofthepox)intensifiedinfrequencyand severity.³³Thesechangeswerenotspeci fictoNorthernItaliancitiesbutwere combinedinthiscontextwiththesecondnotablechangeofthisperiod:significant demographicgrowthandurbanization.

GenoaandVenicewereamongstthemostpopulousEuropeancitiesduringthe fifteenthandsixteenthcenturies.Thesizeoftheformerincreasedfromapproximately51,000peoplein1531to67,000in1579:ariseofathirdoverthecourseof fiftyyears.Venice’spopulationin1563wasestimatedatjustover168,000,having risenfrom115,000attheturnofthesixteenthcentury,presentingalarger percentageincreasethanthatofGenoa.³⁴ Inneithercitywerethechangesin populationsizelinear.Successiveperiodsofnaturaldisasterpromptedconsiderable fluctuations.Overall,however,bothcitiesexperienceddemographicand urbangrowthduringthesixteenthcentury.Theidentificationofpopulation densityasadriverfortheintensi ficationofconcernsaboutcleanlinessisnota newidea.³⁵ Ithasnot,however,beenthetraditionalexplanationforthesemeasuresinRenaissanceItalywheredevelopmentshavebeenmorereadilyattributed toperceptionsofanadvancedformoftheItalianRenaissancestateortheshock causedbydemographiccrisessuchasrecurrentoutbreaksofplague.³ ⁶

(Woodbridge:TheBoydellPress,2013).JannaCoomans, Community,urbanhealthandthe environmentinthelatemedievalLowCountries (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2021).See alsocontributionstoCaroleRawcliffeandClaireWeeda(eds), Policingtheurbanenvironment. For responsibilitiesinmedievalstatutesseeMiriRubin ‘Urbanstatutesandnewcomers’ in Citiesof strangers:makinglivesinmedievalEurope (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2020),pp.33–5. FortheeighteenthcenturyseetheexcellentworkofMariaPiaDonatoandRenatoSansa.

³³OnthelittleiceageseeWolfgangBehringer, Aculturalhistoryofclimate, P.Camiller(trans) (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2010).Onthechangingnatureofplagueinthepremodern periodseeJaneStevensCrawshaw, Plaguehospitals:publichealthforthecityinearlymodernVenice (Aldershot:Ashgate,2012),pp.9,240,and245.GuidoAlfani, Calamitiesandtheeconomyin RenaissanceItaly.TheGrandTouroftheHorsemenoftheApocalypse (Basingstoke:Palgrave Macmillan,2013).JohnHenderson, Florenceundersiege:survivingplagueinanearlymoderncity (LondonandNewHaven:YaleUniversityPress,2019).

³⁴ DanieleBeltrami, StoriadellapopolazionediVenezia (Padua:CEDAM,1954)estimates168,027 in1563butthisfelltojustover120,000followingtheplagueof1575–77andthenroseto134,871 in1581.

³⁵ ForthisargumentinrelationtotheDutchRepublicseeSirWilliamTemple, Observationsupon theUnitedProvincesoftheNetherlands (1672)citedinBasvanBavelandOscarGelderblom, ‘The economicoriginsofcleanlinessintheDutchGoldenAge’ , PastandPresent 205:1(2009),42.This importantarticleattributestherenownedcleanlinessoftheDutchGoldenAgetotheeconomicforces, includinghygienemeasuresessentialtothedairyindustryinahumidclimate.

³⁶ DouglasBiow, CultureofcleanlinessinRenaissanceItaly (IthicaNY:CornellUniversityPress, 2006),pp.11–13.

PopulationgrowthmeantthatbothGenoaandVeniceweresitesofconsiderable urbandevelopmentduringthesixteenthcentury,withitsattendanturbandisruption.Anumberofinitiativesthatweredesignedtoenhanceurbancontexts, includinghousingandinfrastructureprojects,placedastrainoncitiesbyusing significantquantitiesofwaterandgeneratingwasteonalargescale.³⁷ InGenoa,for example,thesignificantquantitiesofwaterrequiredforthebuildingtradeswas drawnfromcisternsaswellaslocalwellsandevendirectlyfromtheaqueduct.³⁸ ManyRenaissancecitiesexistedinastateof ‘semi-perpetualincompletion’ although projectscouldbecompletedwithremarkablecelerity.³⁹ Newbranchesofgovernmentemergedtooverseethemanagementofspecifictypesoflanduse,natural resourcesandelementsoftheenvironment.InGenoaandVenice,thegovernment bodiesforhealthandtheenvironment(whichextendedbeyondHealthOffices,as discussedbelow)alsoemployednewmechanisms(notablysystemsofprivileges)in ordertoencourageinnovationandthedevelopmentofnewtechnologybycitizens andforeignersaliketoaddressthepressingenvironmentalchallengesoftheday. Thisvolume,then,seekstocomplicatetheimageswhichwehaveofthe Renaissance conventionallycharacterizedasatimeofextraordinarypolitical andculturalachievementalongsideintenseurbanproblems. ⁴⁰ Astudyofhealth andtheenvironmentallowshistorianstobridgethesometimes-conflictingcharacterizationsofthegovernanceandsettingoftheseNorthernItaliancities,sinceit ispreciselybecauseofthedevelopedculturesofrecord-keepingthatweknow abouturbanandenvironmentalissues.⁴¹Thisvolumeconcentrateson community-levelmeasures,ratherthanthoserelatedtothecareofthehomeor thebody,tohighlightthreeconceptsthatinfluencedpremodernsocialand environmentalpolicies:balance, flowandcleanliness.⁴²

³⁷ KatherineRinne, ThewatersofRome:aqueducts,fountainsandthebirthoftheBaroquecity (LondonandNewHaven:YaleUniversityPress,2010), p.37.

³⁸ AnnaBoatoandAnnaDecri, ‘Archivedocumentsandbuildingorganisation’,p.383.

³⁹ ASCG,PdC,3-40(18June1470).AnnaBoatoandAnnaDecri, ‘Archivedocumentsandbuilding organization:anexamplefromthemodernage’ inS.Huerta(ed.) Proceedingsofthe firstinternational congressonconstructionhistory (Madrid,2003),p.382referstothereconstructioninstoneofthePonte CalviinGenoainjustover fivemonthsduringthe fifteenthcentury.

⁴⁰ PeterBurke, TheEuropeanRenaissance:centresandperipheries (Oxford:Blackwell,1998), Europe intheRenaissance:metamorphoses1400–1600 (Zürich:SwissNationalMuseum,2016)andJohn JeffriesMartin(ed.), TheRenaissance:Italyandabroad (London:Routledge,2003).

⁴¹FilippodeVivo,AndreaGuidi,andAlessandroSilvestri(eds), ‘Archivaltransformationsinearly modernEurope’ , EuropeanHistoryQuarterly 46(2016)andLiesbethCorens,KatePeters,and AlexandraWalsham(eds), ‘TheSocialHistoryoftheArchive:record-keepinginearlymodern Europe’ , PastandPresent 230suppl.11(2016).

⁴²Onthedistinctionbetweentheenvironmentandlandscape,wherebythelatteractsasarepository ofcollectivememory ‘widelycomparedwithaparchmentandpalimpsestaporoussurfaceuponwhich eachgenerationinscribesitsownvaluesandpreoccupationswithouteverbeingabletoeraseentirely thoseoftheprecedingone’ seeAlexandraWalsham, Thereformationofthelandscape, p.6.Onthe homeandthebodyseeSandraCavalloandTessaStorey, HealthylivinginlateRenaissanceItaly. Fora discussionofthe ‘constellationofassociations[between]purity,whitenessandliquidity’ inthecontext ofcolonialMexicoseeDanielNemser, ‘Triangulatingblackness’,p.359.