Exploring the Variety of Random Documents with Different Content

“All that I have to say to the Democracy is that you want active, earnest organization. Remember that if these Know-Nothings hold together they are sworn compact committees of vigilance. Go to work then. Organize actively everywhere. Appoint your vigilance committees, but take especial care that no Know-Nothings are secretly and unknown to you upon them. Be prepared. I have gone through most of Eastern Virginia, and in spite of their vaunting I defy them to defeat me. There are Indians in the bushes, but I’ll whack on the bayonet, and lunge at every shrub in the State till I drive them out. I tell them distinctly there shall be no compromise, no parley. I will come to no terms. They shall either crush me, or I will crush them in this State.”

Mr. Wise, though his health was impaired, conducted his campaign with extraordinary energy, travelling about 3000 miles, to every point in the State, and speaking fifty times before the election. He was triumphantly elected Governor of Virginia, receiving upwards of ten thousand majority over his Know-Nothing competitor. The impartial verdict of history is that Henry A. Wise did more to kill the KnowNothing party than any other man in the United States.

Many Know-Nothings were elected to Congress from the Northern States, and a few from the Southern States. In the Senate and House of Representatives there were seventy-eight members of that party in 1855. Conspicuous among them all, on account of his prejudices no less than his ability, was Henry Winter Davis, a member of the Thirty-fourth and Thirty-fifth Congresses from Baltimore.

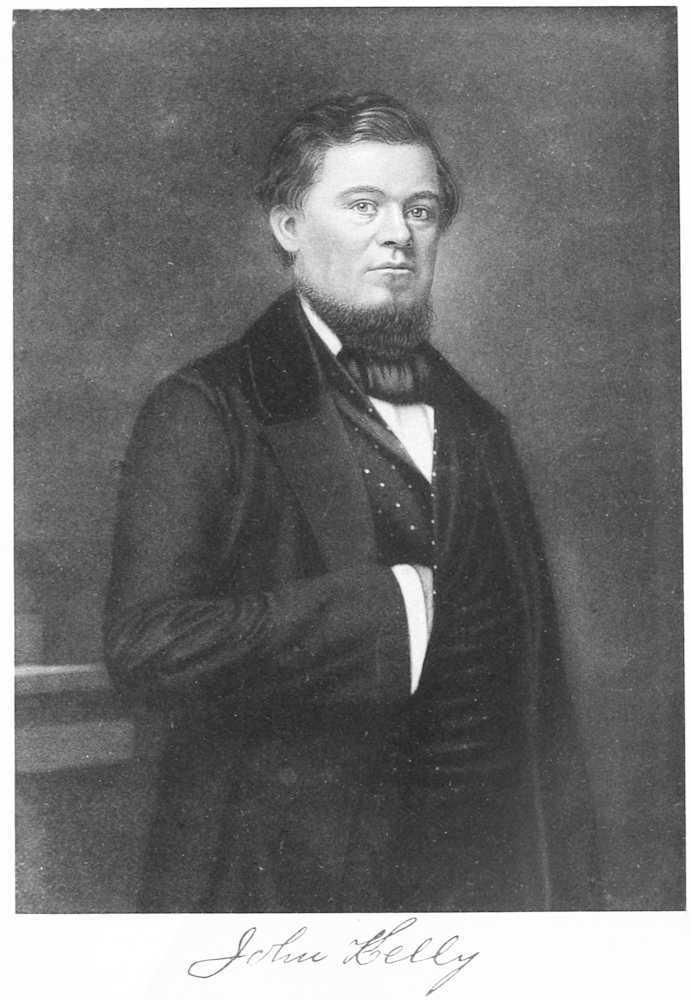

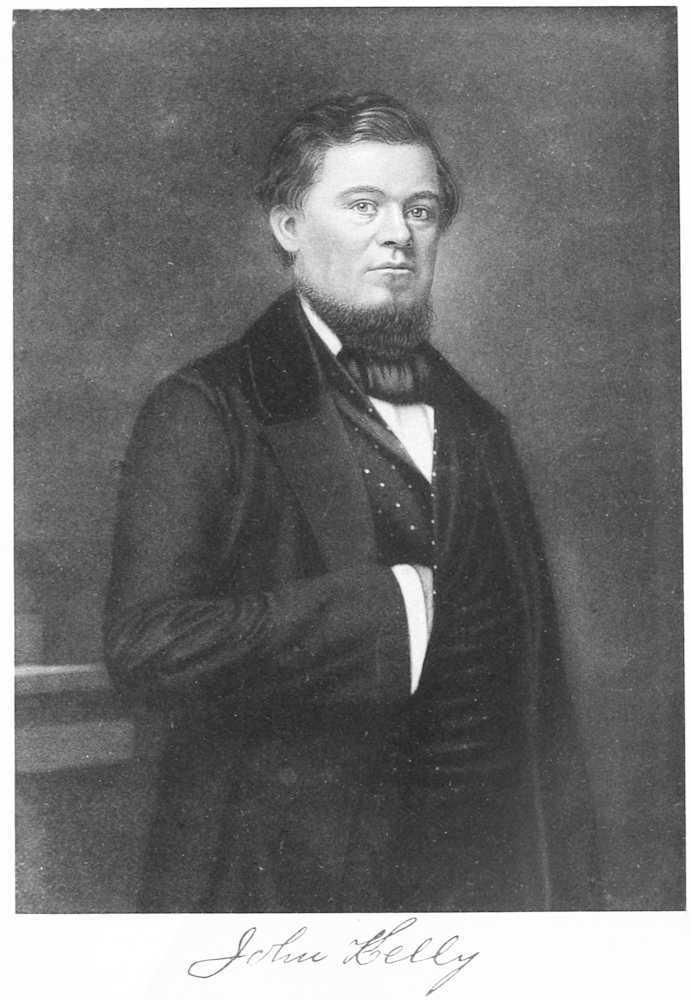

The celebrated controversy upon the floor of Congress between Davis and John Kelly on the Know-Nothing question entitles the Know-Nothing leader to some notice here.

Henry Winter Davis was born at Annapolis, Maryland, August 16, 1817, and received his education at Kenyon College, Ohio, where he was graduated in 1837. His father was an Episcopalian minister. Young Davis was sent to the University of Virginia in 1839 by his aunt, a Miss Winter of Alexandria, Virginia, and entered upon his

preparatory legal studies at that institution. He afterwards opened a law office at Alexandria, where he struggled with poverty for some years, making but little mark in that community, save as an occasional contributor of political essays to the Alexandria Gazette, but applying himself closely to his studies, and becoming an able lawyer. Reverdy Johnson recognized his talents and advised him to remove to Baltimore, where he would find a wider field for their display. Mr. Davis acted on this advice, and made Baltimore his home. He had married a Miss Cazenove of Alexandria, who soon died, and subsequently he married a daughter of John S. Morris, a wealthy and prominent citizen of Baltimore. Mr. Morris opposed the marriage on account of Davis’s peculiar political views.

Henry Winter Davis was a man of genius, with a natural bent for an opposition leader. In person he was handsome, in manners haughty and reserved, in demeanor elegant; and he possessed the gift of a fine oratory, both logical and persuasive. A morose temper and a cynical and cold nature served to heighten the picturesque effect of his character, and to make him delight in fomenting discord and violence. “The ignorant Dutch and infuriated Irish, let them beware lest they press the bosses of the buckler too far,” is said to have been a form of expression he applied to Germans and Irishmen in the course of one of his invectives on the stump in Baltimore. He soon became an acknowledged leader of the Know-Nothings, and no man knew better how to fire the rage and incite to acts of bloodshed the Plug Uglies of that city. Had Davis lived during the era of the Alien and Sedition Laws, his genius probably would have placed him at the head of that conspiracy, and his name would have become famous in history. He was a contemner of the sanctions of authority. The sacredness of institutions handed down from generation to generation unimpaired by the ravages of time, awakened no sense of reverence in the mind of this iconoclast. Burke’s beautiful allusion to the bulwarks of civil society which have been stamped with the “mysterious virtue of wax and parchment,” must have appeared to him only as a figure of rhetoric or a ridiculous fetich. How contemptuously he regarded the warning of Washington to his

countrymen in the Farewell Address against entangling alliances with the nations of Europe is discovered in the following passage, found at page 367, of a book written by Mr. Davis, called “The War of Ormuzd and Ahriman in the Nineteenth Century.”

“They who stand with their backs to the future and their faces to the past, wise only after the event, and refusing to believe in dangers they have not felt, clamorously invoke the name of Washington in their protest against interference in the concerns of Europe. With such it is useless to argue till they learn the meaning of the language they repeat.”

With many similar sophistries he declared it would be wise policy on the part of the United States to take part in European controversies, and pretended to find warrant in the Monroe doctrine for this radical reversal of Washington’s maxim. But that Davis was a demagogue in the offensive sense of the word is evident from the fact that the very advice of General Washington against foreign influence, which he scouted at in his book, was soon after relied upon by the same Davis as his chief argument in Congress for the exclusion of foreigners from the rights and privileges of citizenship. In the course of a Know-Nothing speech, delivered in the House of Representatives, January 6th, 1857, he said: “Foreign allies have decided the government of the country. * * * * Awake the national spirit to the danger and degradation of having the balance of power held by foreigners. Recall the warnings of Washington against foreign influence, here in our midst, wielding part of our sovereignty; and with these sound words of wisdom let us recall the people from paths of strife and error to guard their peace and power.” The insincerity of Davis is further shown from his conduct in regard to the Republican party. He denounced that party in the speech above quoted from, saying, among other things, “the Republican party has nothing to do and can do nothing. It has no future. Why cumbers it the ground?” In the course of a few years he became a Republican, and notwithstanding his former denunciation of them, swallowing at a single breath the most ultra tenets of that party. Consistent only in his inconsistencies, he again prepared to bolt from the Republican

organization shortly before his death, and was the author of the celebrated Wade-Davis Manifesto in 1864, against the renomination of Abraham Lincoln. Once having been invited by a literary society of the University of Virginia to deliver the annual address before that body, he took up some eccentric line of political conduct before the commencement day occurred, and compelled the society in selfrespect to revoke its invitation. He affected the Byronic manner, and the contagion spread to other members of Congress. Roscoe Conkling, after he entered the House of Representatives, is said to have become a great admirer of Henry Winter Davis, and to have fallen into his peculiarities of style as a public speaker. Mr. Conkling’s famous parliamentary quarrel with Mr. Blaine soon after occurred.

Such was the man the Know-Nothings recognized as their leader in the House of Representatives when John Kelly entered that body. In the early part of 1857 Mr. Kelly replied to a sneering assault of Mr. Davis on the Irish Brigade, and in the debate which followed not only proved himself able to cope with the Know-Nothing leader, but in a running debate with Mr. Kennett of Missouri, Mr. Akers of the same State, and Mr. Campbell of Ohio, who entered the lists against him, Kelly established his reputation as one of the best off-hand debaters in Congress.

A few extracts from the speeches on the occasion, which are taken from the CongressionalGlobe, will furnish an idea of the style of the speakers, and the merits of the controversy. In referring to the Presidential election of 1856, and the victory of the Democrats, Mr. Davis said: “The Irish Brigade stood firm and saved the Democrats from annihilation, and the foreign recruits in Pennsylvania turned the fate of the day. They have elected, by these foreigners, by a minority of the American people, a President to represent their divisions. The first levee of President Buchanan will be a curious scene. He is a quiet, simple, fair-spoken gentleman, versed in the by-paths and indirect crooked ways whereby he met this crown, and he will soon know how uneasy it sits upon his head. Some future Walpole may detail the curious greetings, the unexpected meetings, the cross purposes and shocked prejudices of the gentlemen who

cross that threshold. Some honest Democrat from the South will thank God for the Union preserved. A gentleman of the disunionist school will congratulate the President on the defeat of Mr. Fillmore. The Northern gentlemen will whisper ‘Buchanan, Breckenridge and Free Kansas’ in the presidential ear, and beg without scandal the confirmation of their hopes. * * But how to divide the spoils among this motley crew ah! there’s the rub. Sir, I envy not the nice and delicate scales which must distribute the patronage amid the jarring elements of that conglomerate, as fierce against each other as clubs in cards are against spades. * * The clamors of the foreign legion will add to the interest of the scene. They may not be disregarded, for but for them Pennsylvania was lost, and with it the day. Yet what will satisfy these indispensable allies, now conscious of their power? That, Sir, is the exact condition of things which will be found in the ante-chamber—exorbitant demands, limited means, irreconcilable divisions, strife, disunion, dissolution—whenever the President shall have taken the solemn oath of office and darkened the doors of the White House.

“The recent election has developed in an aggravated form every evil against which the American party protested. Foreign allies have decided the government of the country—men naturalized in thousands on the eve of the election. Again in the fierce struggle for supremacy, men have forgotten the ban which the Republic puts on the intrusion of religious influence on the political arena. These influences have brought vast multitudes of foreign born citizens to the polls, ignorant of American interests, without American feelings, influenced by foreign sympathies, to vote on American affairs; and those votes have, in point of fact, accomplished the present result.”

Mr. Kelly replied to the Know-Nothing leader. He said: “I rise for the purpose of submitting as briefly as I can a few remarks in reply to the very extraordinary speech of the honorable member from Baltimore city. In the great abundance of his zeal to assail the President of the United States, the gentlemen from Baltimore could not permit so good an occasion to pass without hurling his pointless invectives against my constituents, in terms and temper which

demand a reply. * * * His ambition seems restless and insatiable, for he cannot conclude his speech without trying a bout with what he denominates the ‘Irish Brigade.’ What particular class of our fellowcitizens this fling was aimed at, I am at a loss to conjecture. There is a body known to history under that appellation—a body of historical reputation, whose deeds of bravery on every battle-field of Europe have long formed the glowing theme for the poet’s genius and the sculptor’s art. But, sir, they were too pure to be reached by the gentleman’s sarcasm—too patriotic to be measured by his well conned calculation of the ‘loaves and fishes’ which have unfortunately slipped through his fingers—too brave to be terrified by the menaces or insults of those who would justify brutal murder— the murder of defenceless women and helpless children—the sacking of dwellings and the burning of churches, under the insolent plea of ‘summary punishment.’ Sir, the Irish Brigade of history was composed of patriots whom oppression in the land of their birth had driven to foreign countries, to carve out a home and a name by their valor and their swords. The brightest page of the history of France is that which records the deeds and the names of the ‘Irish Brigade.’ France, however, was not the only country in which the Irish Brigade signalized its devotion to liberty, and its bravery in achieving it. Sir, the father of your own navy was one of that glorious band of heroes who shed lustre on the land of their birth, while they poured out their life-blood for the country of their adoption. John Barry was a member of the Irish Brigade in America—he, who when tempted by Lord Howe with gold to his heart’s content, and the command of a line-of-battle-ship, spurned the offer with these noble words: ‘I have devoted myself to the cause of my adopted country, and not the value or command of the whole British fleet could seduce me from it.’ He, who when hailed by the British frigates in the West Indies and asked the usual questions as to the ship and captain, answered: ‘The United States ship Alliance, saucy Jack Barry, half-Irishman, half-Yankee. Who are you?’ Sir, saucy Jack Barry, as he styled himself, was the first American officer that ever hoisted the Stars and Stripes of our country on board a vessel of war. So soon as the flag of the Union was agreed on, it floated from the mast-head of

the Lexington, Captain John Barry. But Captain John Barry was not the only member of the ‘Irish Brigade’ whose name comes down to us with the story of the privations and bravery of our revolutionary struggle. Colonel John Fitzgerald was also a member of that immortal band. Of this member of the ‘Irish Brigade’ I will let the still living member of Washington’s own household, the eloquent and venerable Custis speak:

“‘Col. Fitzgerald,’ says G. W. P. Custis in his memoirs of Revolutionary Heroes, ‘was an Irish officer in the Blue and Buffs, the first volunteer company raised in the South, in the dawn of the Revolution, and commanded by Washington. In the campaign of 1778 and retreat through the Jerseys, Fitzgerald was appointed aidde-camp to Washington. At the battle of Princeton occurred that touching scene, consecrated by history to everlasting remembrance. The American troops, worn down by hardships, exhausting marches and want of food, on the fall of their leader, that brave old Scotchman, General Mercer, recoiled before the bayonets of the veteran foe. Washington spurred his horse into the interval between the hostile lines, reigning up with the charger’s head to the foe, and calling to his soldiers, ‘Will you give up your General to the enemy?’ The appeal was not made in vain. The Americans faced about and the arms were leveled on both side—Washington between them— even as though he had been placed as a target for both. It was at this moment Colonel Fitzgerald returned from conveying an order to the rear—and here let us use the gallant veteran’s own words. He said: ‘On my return, I perceived the General immediately between our line and that of the enemy, both lines leveling for the decisive fire that was to decide the fortunes of the day. Instantly there was a roar of musketry followed by a shout. It was the shout of victory. On raising my eyes I discovered the enemy broken and flying, while dimly, amid the glimpses of the smoke, was seen Washington alive and unharmed, waving his hat and cheering his comrades to the pursuit. I dashed my rowels into my charger’s flanks and flew to his side, exclaiming, ‘Thank God, your Excellency’s safe.’ I wept like a child for joy.’”

“This is what history tells us of another member of the ‘Irish Brigade.’ Now, Sir, if the gentleman from Maryland will only suppress his horror, and listen with patience, I will tell him what tradition adds concerning this brave aid-de-camp of Washington—this bold and intrepid Irishman. After peace was proclaimed and our independence achieved—after the Constitution had been put in operation, and Washington filled the office of chief-magistrate of the nation—he sent for his old companion in arms, then living in Washington’s own county of Fairfax, and invited him to accept the lucrative office of collector of the customs for the port of Alexandria. This tradition will be found to correspond with the records of the Treasury Department, on which may be read the entry that Colonel John Fitzgerald was appointed collector of the customs at Alexandria, Virginia, by George Washington, President of the United States, April 12, 1792. Thus we find that the Father of his country, were he now living, would come under the denunciations of the gentleman from Maryland, and his Know-Nothing associates, for conferring office on one of the ‘Irish Brigade.’

“The gentleman from Baltimore city professes great devotion to the memory and fame of the illustrious Clay. He was the gentleman’s oracle while living. Hear his eloquent voice coming up to us as if from his honored grave. He, too, is speaking of the ‘Irish Brigade,’ and in his warm, honest and manly soul the only words which he can find sufficiently ardent to express his feelings are ‘bone of our bone, and flesh of our flesh.’ ‘That Ireland,’ exclaims the orator of America in a speech delivered as late as 1847, ‘which has been in all the vicissitudes of our national existence our friend, and has ever extended to us her warmest sympathy—those Irishmen who in every war in which we have been engaged, on every battle-field from Quebec to Monterey, have stood by us shoulder to shoulder and shared in all the perils and fortunes of the conflict.’ If anything, Mr. Chairman, were wanting after this to ennoble the ‘Irish Brigade,’ and give it its proper and constitutional position in the family of American freemen, it is the obloquy of His Excellency Henry J. Gardner of Massachusetts, and the Hon. Henry Winter Davis, of Baltimore.

“I now propose, Mr. Chairman, to address myself for a few moments to the honorable gentleman from Missouri (Mr. Akers), who is, I learn, a minister of the gospel. While his friend from Baltimore city exhausts all his powers upon the ‘Irish Brigade,’ he, with an equal stretch of fancy, but a much vaster stride over space, obtrudes himself at a bound into the cabins of the Irish peasantry, far away across the Atlantic. Hailing from a State first settled by Catholics, whose chief city was named by its pious founders after the sainted crusader King of France, the gentleman from Missouri calls on you to hear the Irish priest beyond the Atlantic holding converse with his enslaved parishioners. Mr. Chairman, from boyhood to manhood, I have known more priests of native and foreign birth than Mr. Akers ever saw. I have seen them at the cradle of infancy; I have been with them at the death-bed of old age; but, sir, my ears are only those of a man; I never heard a word of the speeches the gentleman from Missouri puts into their lips. Is it not known, sir, to every candid and impartial traveler who has visited that beautiful but ill-fated Island that the only true, devoted, loyal, self-sacrificing friend that the Irish peasant has in the land of his birth is the Catholic priest? He stands between him and the oppression of his haughty, blood-stained rulers; and when he cannot ameliorate his condition he bears on his own shoulders his full share of the burden. In suffering and misfortune he administers to him the consolations of his religion and the counsel of a friend; he sympathizes with him in all his trials, and when the minister of a strange faith, armed with all the terrors of the law, sends his bailiffs and his minions to seize the very bed on which his sick wife is preparing to meet the God of her fathers—when under the maddening spectacle a momentary burning for revenge perhaps seizes upon his agonized soul—the priest is by his side whispering in his ear ‘Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord’; takes him by the hand, provides with his last penny for the safe removal of the sick and the helpless, and leaves them not until the hour of their trial is passed—a trial that will continue to harrass and oppress the Irish Catholic so long as the national Church of England prolongs a life of debauchery and vice on the plunder and pillage of the Irish peasant.”

Mr. Kelly made a deep impression on the House. The KnowNothing members held a consultation while he was speaking, and decided that he must be interrupted and overcome if possible by a running fire of cross-questions. Luther M. Kennett of Missouri, formerly Mayor of St. Louis, and Lewis D. Campbell of Ohio, Chairman of the Committee of Ways and Means, were selected to open fire upon him. Mr. Kennett began by saying, “Will the gentleman from New York allow me to interrupt him for a moment?”

Mr. Kelly: “Certainly, sir.”

Mr. Kennett: “I see, Mr. Chairman, that my colleague to whom the gentleman refers, is not in his seat. I will, therefore, with his permission, say that I think he has unintentionally misinterpreted my colleague’s remarks. The inference which I drew from the argument of my colleague on this floor was that he was opposed to the consolidation of political and religious questions and to the proscribing of any man on account of his religious belief—and such are the principles and policy of the American Party. My colleague said further that the American Party was the first party that ever introduced that principle in their political platform.”

Mr. Kelly: “I must insist, Mr. Chairman, with all deference to the gentleman from Missouri, that I have not misunderstood the remarks of his colleague. I listened to his speech, as I have already said, with attention, and read it very carefully as it is printed in the Globe, and as it now appears in that paper to speak for itself. While I admit an apparent effort on the part of the gentleman from Missouri to look liberal, I must be permitted to remark that he seems no way solicitous to talk liberal, and an unbiased perusal of the gross libel which he has published in the Globe concerning the Irish Catholic priesthood will lead his colleague, however reluctantly, to the same conclusion. But the gentleman only acts out the principles and ritual of the midnight order, which conceals all it can, and denies everything.”

Mr. Kennett: “I will answer the gentleman more fully in my own speech, and will here state that I am ready to answer any question

he may propound.”

Mr. Kelly: “Then I ask the gentleman did he or does he now give his adhesion to the platform of principles adopted by the American Party in Philadelphia in February, 1856? If so, does not the gentleman by his own showing concur in the principle of proscribing Catholics because of their religious belief? I allude to the fifth article of the American platform.”

Mr. Kennett: “I will answer the gentlemen by referring him to the platform laid down by the American Party of my State which proscribes no man because of his religious belief. And now let me further say that the gentleman is in error when he asserts that this debate was commenced by my colleague. It was introduced by Mr. Bowie of Maryland, in his animadversions upon his colleague, Mr. Davis.”

Mr. Kelly: “The gentleman certainly is in error, for Mr. Davis himself in his wild foray against the ‘Foreign Brigade,’ unnecessarily and unfoundedly attributed the defeat of his party in the last election to the ‘religious influences’ which brought so many alien citizens to the polls. The gentleman has not, however, yet answered my question.”

Mr. Kennett: “I am sorry I cannot suit the gentleman in my reply. He says the Democratic party are a unit, that they everywhere fully endorsed the Kansas-Nebraska bill; I say they nevertheless claim the largest liberty in its construction, and that construction is notoriously different in different sections of the Union among brethren of the same political faith. Now, the American party also needed a platform for the Presidential canvass, and that of February last was put forth for that purpose. If it was not perfect, it was the best we could get, and we had to take it, those of us that it did not precisely suit, with the mercantile reservation, ‘Errors excepted.’ Was your President, the present occupant of the White House, elected by a majority of American-born citizens? On the contrary, without the foreign vote, which was cast for him almost unanimously, he never would have been elevated to the position he now occupies.”

Mr. Kelly: “Suppose he was not elected by American-born votes (which was very likely the case), were not the principles advocated by the party which elected Mr. Pierce national principles, without the benefit too of ‘Errors excepted’? Was there anything in the platform laid down at Baltimore by the convention which nominated him violative of the spirit or letter of the Constitution of the United States?”

Mr. Kennett: “I have not charged the contrary to be so. My point is that the foreign-born vote holds the balance of power in our country, that that vote is almost always on the Democratic side, and thus it shapes the policy and action of the Government. This I consider wrong.”

Mr. Kelly: “I will say to the gentleman that the illiberal and narrow policy parties have pursued in this country has contributed much to drive both native and foreign-born Catholics in self-defense into the Democratic party. That this is true is proved by the fact which you know full well, Mr. Chairman [Mr. Humphrey Marshall], that the large Catholic vote of Kentucky and Maryland had always been found with the Whig party, until the Know-Nothing monster and its protean brood of platforms drove them in self-respect as well as in selfdefence into the ranks of the national Democracy, where they have found repose and peace under the broad shadows of the Constitution. I will add further, that with the exception of two terms the administration of this Government has been in the hands of the Democratic party. It appears to me, therefore, that the fact that the foreign-born population, in the exercise of the elective franchise being always found on the side of the dominant party, is rather doubtful evidence that they are not as loyal to the country as any other class of voters. The high state of prosperity which the country has attained under Democratic rule would, I should think, lead to quite a different conclusion.”

Mr. Kennett: “The Democratic party have been sharper and more successful hitherto in bidding for their votes than we. Not that we would not have won them too, had it been in our power. Office-

seekers are all in love with German honesty and the ‘sweet Irish brogue.’”

Mr. Campbell, of Ohio: “I have no desire to interrupt the gentleman from Missouri, or to interfere with the very interesting colloquy between him and the gentleman from New York. I have had something to do with this matter of Americanism myself; something to do with the tariff, and, like the gentleman from Missouri, I have been a Whig. I think the greatest statesman of America was stricken down by a religious influence.”

Mr. Kelly: “To whom does the gentleman refer?”

Mr. Campbell: “I refer to Mr. Clay of Kentucky. I well remember when he was last a candidate—in 1844—that there was an individual on the ticket with him—a distinguished gentleman, Theodore Frelinghuysen and I know of my own personal knowledge that a priest of the Catholic Church said that because Theodore Frelinghuysen was placed on the ticket for Vice-President, therefore the influence of the Catholic Church of the United States would be exercised against the ticket.”

Mr. Kelly: “Supposing this to be so, does the gentleman mean to argue that because an individual Catholic priest used such a remark it is sufficient ground upon which to condemn and disfranchise the four millions of Catholics in this country?”

Mr. Campbell: “No, sir, by no means; nor would I interfere with their religion, even though it was true that they had done so. The point I make is this: That because Theodore Frelinghuysen was nominated on the ticket with Henry Clay, who was recognized as one of the greatest statesmen of his age, the influence of the Catholic Church—I mean especially that of the foreign Catholic Church, I do not include the American Catholic Church—was brought to bear against him; and wherever you find a foreign Catholic vote in referring to the election of 1844 you will find, particularly in your large cities where the power was wielded, that the power was exercised for the prostration of Harry of the West, for the reason, as

admitted to me in person by a priest of your church, that Theodore Frelinghuysen was a leading Presbyterian and President of the American Protestant Bible Society; and it is against that spirit on the part of foreign Catholic influence in this country, which has sought to control, through the power of its Church, the destinies of this great nation that I make war.”

Mr. Kelly: “Allow me to say that I am a native-horn citizen of Irish parents; and I wish to say to this House, and to the country, that no such feelings actuate the Catholic Christians of this Republic. There may be individual cases, but I deny that such influences have anything to do with the Catholic population. And Mr. Clay himself, in writing a letter on this very subject in the canvass referred to, made a public acknowledgement that he had as much confidence in the Catholic people as he had in any other religious sect in this Union. That letter was published in a speech which I made in this House last session, and the gentleman from Ohio can find it in the records of the House. To convict the gentleman from Ohio, however, of misrepresenting Harry of the West in this matter, I will again quote the same extract from the letter referred to:

“‘Nor is my satisfaction diminished by the fact that we happen to be of different creeds; for I never have believed that that of the Catholic was anti-American and hostile to civil liberty. On the contrary, I have with great pleasure and with sincere conviction, on several public occasions, borne testimony to my perfect persuasion that Catholics were as much devoted to civil liberty, and as much animated by patriotism as those who belong to the Protestant creed.’”

“I have already quoted from Mr. Clay’s speech delivered in 1847, four years afterwards, enough to show that his views and sentiments in reference to foreign-born voters and religious creeds underwent no change. But it was ever Mr. Clay’s misfortune to be damaged by his friends. We have proof this evening that the fatality follows him to the grave.”

In this debate, Mr. Kelly, who was the only Catholic in Congress, sustained the concentrated charge of the leading Know-Nothing members, and in the estimation of the House had the best of the argument over them all. His speech was published and read throughout all parts of the Union, and was received with manifestations of approval and pride by Democrats generally, but especially by Catholics and adopted citizens.

In the celebrated Hayne-Webster debate in the Senate of the United States on the Foot Resolution in 1830, Andrew Jackson, then President, was so much pleased with Col. Hayne’s speech that he caused a number of copies to be struck off on satin, and placed one of them on the walls of his library in the White House.[9] The speech of John Kelly, from which the preceding extracts are taken, was also published on satin, and is still preserved in many households throughout the country as a souvenir of the dark days of KnowNothingism, and of the gallant stand that was made in the House of Representatives against the proscriptionists by the future leader of the New York Democracy.

During another debate in Congress—that of May 5, 1858—on the bill for the admission of Minnesota into the Union, introduced by Alexander H. Stephens, Chairman of the Committee on Territories, Henry Winter Davis again attacked those he called “unnaturalized foreigners;” and Mr. John Sherman, then a member of the House, and at present a Senator from Ohio, and a recent aspirant for the Presidency, declared that “Ohio never did allow unnaturalized foreigners to vote, and never will.” Mr. Muscoe R. H. Garnett, of Virginia, made a fierce attack on the same class, designating them as the “outpourings of every foreign hive that cannot support its own citizens.” When these tirades were made, Mr. Kelly rose to address the House in reply, but so bitter was the native American feeling on the subject, and especially since his refutation of the sectarian and anti-foreign speech of Davis in the preceding year, that John Sherman resorted to every parliamentary quibble to cut off Kelly’s speech. “Gentlemen here,” Mr. Kelly said, “directed many of their

arguments against emigration and against the naturalization of foreigners. I intend to confine my remarks to that particular branch of the subject.” At this point Mr. Sherman objected.

Mr. Sherman, of Ohio: “I rise to a question of order. The rule requires that the debate shall be pertinent to the question before the House. If the gentleman desires to make a speech upon the benefits of emigration I hope he will make it in Committee of the Whole. Such debate is not in order here.”

Mr. Kelly: “What I shall say will be pertinent to the issue before the House.”

Mr. Sherman: “I insist on my question of order. I would inquire whether the subject of emigration, which is manifestly the question which the gentleman intends to discuss, is debatable on this bill? I do not wish to embarrass the gentleman, but desire, if he wants to debate that subject, that he shall do it in the Committee of the Whole on the state of the Union.” This objection by Mr. Sherman to Mr. Kelly’s continuing the discussion which he himself had just been indulging in, shows that Kelly’s method of handling the subject was not relished by the proscriptionists. Elihu B. Washburn, of Illinois, afterwards Minister to France, here interposed in favor of fair play.

Mr. Washburn: “I hope by unanimous consent the gentleman from New York will be permitted to continue his speech. He is upon the floor now, and the matter of naturalization is involved more or less in the merits of the question before the House.” But Mr. Sherman was ready with another quibble.

Mr. Sherman: “If unanimous consent be given, I am willing to go into Committee of the Whole on the state of the Union and allow the gentleman to speak, but I must object to it in the House.”

Mr. Wright, of Georgia: “I would remark that the gentleman from Virginia (Mr. Jenkins) introduced this particular subject yesterday, and occupied twenty-five minutes in its discussion.”

Mr. Kelly: “It is singular that gentlemen should make objection, when it is a well-known fact that the whole discussion on this bill has

directed itself to that particular point. But I think there is a disposition on the part of the House to let me go on.”

Several Members: “There is; go ahead.”

The Speaker: “Does the Chair understand that unanimous consent is given to the gentleman’s proceeding?”

Mr. Lovejoy: “Not unless he is in order.”

Mr. Morris, of Pennsylvania: “I object; because if the gentleman is allowed to proceed, other gentlemen must be allowed to speak in reply, and thus we would have a general debate in violation of the rules of the House, and I will not agree to violating the rules of the House.”

Mr. Kelly: “Inasmuch as there are objections I withdraw my appeal. I do not desire to force myself upon the House.”

Thus did the Know-Nothings wince under the lash of John Kelly of New York. Had he chosen to insist, he would have been heard, for he was now one of the leaders of the House, and the majority would have found a way to secure him the floor. He was the most formidable enemy of the Know-Nothings in the Northern States, for he knew how to act as well as to talk. Dreamers and visionaries write fine theories, but only great men reduce them to practice. Mr. Kelly’s youth and early manhood were passed at a period when native American bigotry and intolerance were burning questions in State and National affairs. He had been taught by observation, and a study of the fathers of the government, that the best service he could render his country was to make war on Know-Nothingism. He had met the leaders of that party in their strongholds in the city of New York, and vanquished them. Before his day there were clubs and factions, and local leaders and captains of bands—Bill Poole and his Know-Nothings, Isaiah Rynders and his Empire Club, Arthur Tappan and his Abolitionists, Mike Walsh and his Spartans, Samuel J. Tilden and his Barnburners, Charles O’Conor and his Hunkers—but the born captain had not appeared to mould the discordant elements to his will, and make them do the work that was to be done. When

John Kelly struck the blow at Know-Nothingism at the primary election on the corner of Grand and Elizabeth streets, already described, and drove out the ballot-box stuffers, the people of New York instantaneously recognized a man behind that blow, and everybody felt better for the discovery. When he ran against the celebrated Mike Walsh for Congress, one of the most popular characters who ever figured in New York politics, and beat him, the native American proscriptionists were glad that John Kelly was out of the way, for while they feared him in local politics, they persuaded themselves that he would be swallowed up in obscurity among the great men at Washington, and that he would be heard of no more. Given a big idea lodged in the centre of a big man’s head, and be sure fruit will spring from the seed. Kelly carried his idea with him to Congress, and hostility to Know-Nothingism marked his career there, as it had done at home.

When James Buchanan became President, John Kelly became one of the leaders of the Administration party in Congress. He was then thirty-four years old. One day General Cass, Secretary of State, visited the Capitol, and in conversation with a friend said: “Look at John Kelly moving about quietly among the members. The man is full of latent power that he scarcely dreams of himself. He is equal to half a dozen of those fellows around him. Yes, by all odds, the biggest man among them all. The country will yet hear from Honest John Kelly.” These words of General Cass, uttered in his imposing George-the-Third style of conversation, shortly after were repeated to old James Gordon Bennett, the friend of Kelly’s boyhood, and the editor took early opportunity to mention Honest John Kelly in the Herald, and frequently afterwards applied the same title to him. The appellation struck the public as appropriate, and soon passed into general use. The subject of this memoir has been called “Honest John Kelly,” from that day to this. In a letter to the present writer, in 1880, the late Alexander H. Stephens said: “I have stood by John Kelly in his entire struggle, and have often said, and now repeat, that I regard him as the ablest, purest and truest statesman that I have ever met with from New York.”

Mr. Buchanan was urged by Mr. Kelly to appoint Augustus Schell Collector of the Port of New York. Other members of the New York delegation in the House, and both the New York Senators opposed the selection of Mr. Schell. Mr. Seward was vehement in his opposition. But John Kelly stuck with the tenacity of Stanton in the War Department, or Stonewall Jackson in the battle-field. The President nominated Mr. Schell Senator Clay of Alabama reported the nomination favorably from the Committee of Commerce, William H. Seward and the others were overborne, and Mr. Schell was confirmed by the Senate.

When Mr. Kelly entered upon his political career, to be a foreigner, or the son of a foreigner, in New York, in the opinion of the intolerant of both parties, was deemed a matter that required an apology, or at least an explanation. In 1857 one of the leading representative men of the Federal Administration in New York was John Kelly, and those who had been persecuted and oppressed before were recognized and advanced equally with all others in the city and State of New York; and the vanishing Know-Nothings at last realized that the absent Kelly had dealt them heavier blows from Washington than he ever delivered in New York. In these later and happier days men are no longer ashamed to be called the sons of Irishmen, and at the festive board of the Irish societies the notable ones of the country gather to make eloquent speeches and drink rousing toasts. But while some men forget, true Irishmen and true descendants of Irishmen have not forgotten their Horatius at the bridge in the brave days of old. John Kelly, were he a man of vanity, in contrasting the auspicious scenes of to-day with those of the dark days of 1844 and 1854, and in viewing his own part in effecting the change, could not fail to find much cause for pride and complacent reflection; but vanity is not his weakness.

JohnKelly

(AT

THE AGE OF 35 YEARS.)

Mr. Kelly went to Washington in the winter of 1855 to succeed the brilliant Mike Walsh in the House of Representatives. How did the weighty statesmen receive him? He went into their midst a bigboned, heavy-browed, brawny stranger, with his far-seeing eye, and firm solid step, and as he strode in among the Solons of Washington they all felt an instantaneous conviction from his conversation and bearing that in the society of the most eminent men of the Republic John Kelly was exactly where he was entitled to be. He flattered no great man by the least symptom of being himself flattered by his notice. He measured his strength in discussion with the most celebrated men in Congress, and feared the face of none. At their social gatherings he responded to the brilliant bonmots of the wits of the capital by quiet strokes of humor, and anecdote, and story, that sent bursts of merriment through the circle, delighting the sensible, and penetrating even those who encased themselves in triple folds of aristocratic reserve.

There is nothing artificial about him, but he has been always, and was so particularly in those days, the child of nature, with no shadow of pretension or affectation in his manners. He was not simply a man lifted up from the ranks of toil to be noticed by the world’s favored ones, but he was endowed with that greatness of soul which always distinguishes its possessor above his fellows, whether his lot be cast in the highest or lowest situation of life. It is not strange that New York has felt, and will continue to feel, the moral influence of this man as long as he continues to take part in its affairs, loved by the masses for his lion-like courage, and by friends who meet him face to face in retirement for his almost womanly gentleness, while for obvious reasons he is hated and vilified by those who do not appreciate such qualities. And this courage and gentleness and unruffled equanimity come all in a breath, perfectly natural and free, for they come of their own accord. His composure under all circumstances has often been remarked upon, and in the hurly-burly of New York politics, and the headlong rush of the tide of life in the great metropolis, John Kelly is as sedate and recollected as the ascetic in his cloister. But there is nothing of

sourness in his temper. Reflecting much at all times, he possesses the rare gift of thinking while he is talking, and when he is expressing one idea his thoughts never outrun the present sentence, as do those of nine-tenths of people, to frame words for the next one. He does not, in short, think of what he is going to say next, but of what he is saying now. Among the finer shades of character that distinguish one man from another it is extremely difficult to define that untranslatable something which gives to each person his individuality; but this intentness of Mr. Kelly upon the immediate subject under consideration, both as listener and talker, is wonderfully attractive, and constitutes one of the subtle forces of his character as a political leader. This faculty of concentration belongs exclusively to original minds. Self-reliant, and borrowing nothing from others as to style or conduct, he gets at the point without labored approaches, and acts great parts with a happy carelessness. When others have been cast down and worried with care over affairs in which Mr. Kelly was more interested than themselves, his elastic spirit has not given way. Loving thus the sunshine, he affords a conspicuous example of the truth of the inspired words, “a merry man doeth good like a medicine.” Nothing has ever dispelled his cheerfulness. Defeat, deprivation of office, desertion by those he trusted, and who owed all they were to him, have neither embittered him, cast him down, daunted his courage, nor shaken his faith in himself. Domestic afflictions such as few men ever know—the death of his entire family—have come upon him, and while the keen shaft scarred the granite, his constancy has remained, and neither head nor chastened heart succumbed to misanthropy or rebellion against Providence. Surely something more substantial than wit, or genius, or equable temper was required to sustain John Kelly in the trials he has borne. The natural can only accomplish the natural, but a good man draws from supernatural fountains to replenish the well-springs in the arid plains of the desert, and Christianity, not for holiday show but daily use, must have been this man’s sheet-anchor.

Those acquainted with Mr. Kelly will be proper judges of the fidelity or shortcomings of this picture. They who have read the

absurd delineations of him in some of the newspapers, and accept them without more inquiry as reliable, may reject this description of his character as contradictory of their preconceived notions on the subject. There is a third class of witnesses—an increasing class— perhaps more impartial than the two former ones, whose testimony on the point is important. These are strangers who have formed violent prejudices against the man after reading certain newspapers, but who on becoming acquainted with him repudiate their own opinions as rash and preposterously unjust.

“Oh!” but say his enemies, “this is not a fair test; Kelly is plausible and fair-spoken, and has great personal magnetism. Strangers when they meet him fall under his spell.” The objection is a weak one, for these strangers never relapse into their former absurd opinions after they have gone away, and withdrawn themselves out of his spell. Let such strangers decide as to the faithfulness or unfaithfulness of the picture sketched here. A case of the kind occurred at the Cincinnati Democratic Convention in 1880. A delegate to the Convention from the State of Rhode Island was very severe on John Kelly. He had been reading an unfriendly newspaper. He denounced him as a boss, and uttered many just sentiments on the evils of bossism. While he was speaking John Kelly and Augustus Schell passed by, and the former was pointed out to him. “Is that Kelly?” said he. “Well, he doesn’t look much like a New York rough, or bar-room bully anyhow. I have been told he was both.” An introduction followed, and a conversation took place between the delegate and the subject of his recent execrations. “I am greatly obliged to you,” said the Rhode Island delegate to the author of this memoir, who gave the introduction, after Mr. Kelly had parted from him and re-joined Mr. Schell. “I honestly detested John Kelly, as a low, ignorant ward politician, who had conducted a gang of rowdies to this Convention to try and overawe it. So I had been told again and again. Now I don’t believe a word of it. I never talked to a more sensible man, and modest gentleman than John Kelly. This opens my eyes to the whole business.”

In the course of this chapter particular attention has been directed to Mr. Kelly’s war on Know-Nothingism as his chief claim to distinction and the gratitude of his country during his younger days. He became identified with the cause of equal rights in the minds of adopted citizens of various nationalities, especially of the Irish, and contributed as much, after Henry A. Wise, towards the overthrow of the Know-Nothing party, as any man in the United States. The adopted citizens were proud of their champion, and the place which he gained in their affections became so deep that, like Daniel O’Connell in Ireland, he could sway them by his simple word as completely as a general at the head of his army directs its movements. Mr. Kelly never abused this confidence, and consequently has retained his influence to the present day. Many have marvelled at his hold on the people of New York, as great when out of power, as when he has had the patronage of office at his disposal. Among the causes which have conspired to give him the largest Personal following of any man of the present generation, his patriotic services in the old Native American and Know-Nothing days must be reckoned among the chief. Such a hold Dean Swift had upon Irishmen in the eighteenth century. Nothing could break it, nothing weaken it, the King on his throne could not withstand the author of the Drapier’s Letters in his obscure Deanery in Ireland. It is fortunate John Kelly is a just and honest man, unmoved by clamor, not to be bribed by place or power, nor seduced by the temptations of ambition; for were it otherwise, his sway over great multitudes of men might enable him to lead them to the right or left, whichsoever way he might list, a momentous power for good or evil. The politician who ignores this man’s influence, the historian who omits it from his calculation of causes, has not looked below the surface of things, and knows nothing of the real state of affairs in the city and State of New York.

Alexander H. Stephens was acquainted with John Kelly for over a quarter of a century; came into daily contact with him for four years on the floor of Congress; served with him for two years on the Committee of Ways and Means in the House; and his estimate of Mr.

Kelly’s character, referred to at a former page, is entitled to respectful consideration from every man in the United States, especially on the part of those who know nothing about him except what they have read in partisan newspapers. “I have often said, and now repeat,” declared Georgia’s great Commoner, “that I regard John Kelly as the ablest, purest and truest statesman that I have ever met with from New York.”

FOOTNOTES:

[6] Cleveland’s Life of A. H Stephens, p. 469.

[7] The greater number of those he was addressing were Know-Nothings.

[8] Cleveland’s Life of A. H. Stephens, p. 472, etseq.

[9] The Carolina Tribute to Calhoun (Rhett’s oration), p. 350.