City Living

How Urban Dwellers and Urban Spaces

Make One Another

QUILL R KUKLA

3

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kukla, Quill R, author.

Title: City living : how urban dwellers and urban spaces make one another / Quill R Kukla.

Description: New York, NY, United States of America : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021022701 (print) | LCCN 2021022702 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190855369 (hb) | ISBN 9780190855383 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Sociology, Urban. | City dwellers. | City planning. | Cities and towns. | Public spaces.

Classification: LCC HT111 .K67 2021 (print) | LCC HT111 (ebook) | DDC 307.76—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021022701

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021022702

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190855369.001.0001 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For and with Eli and Berlin

Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.

Jane

Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Figures

Color Images

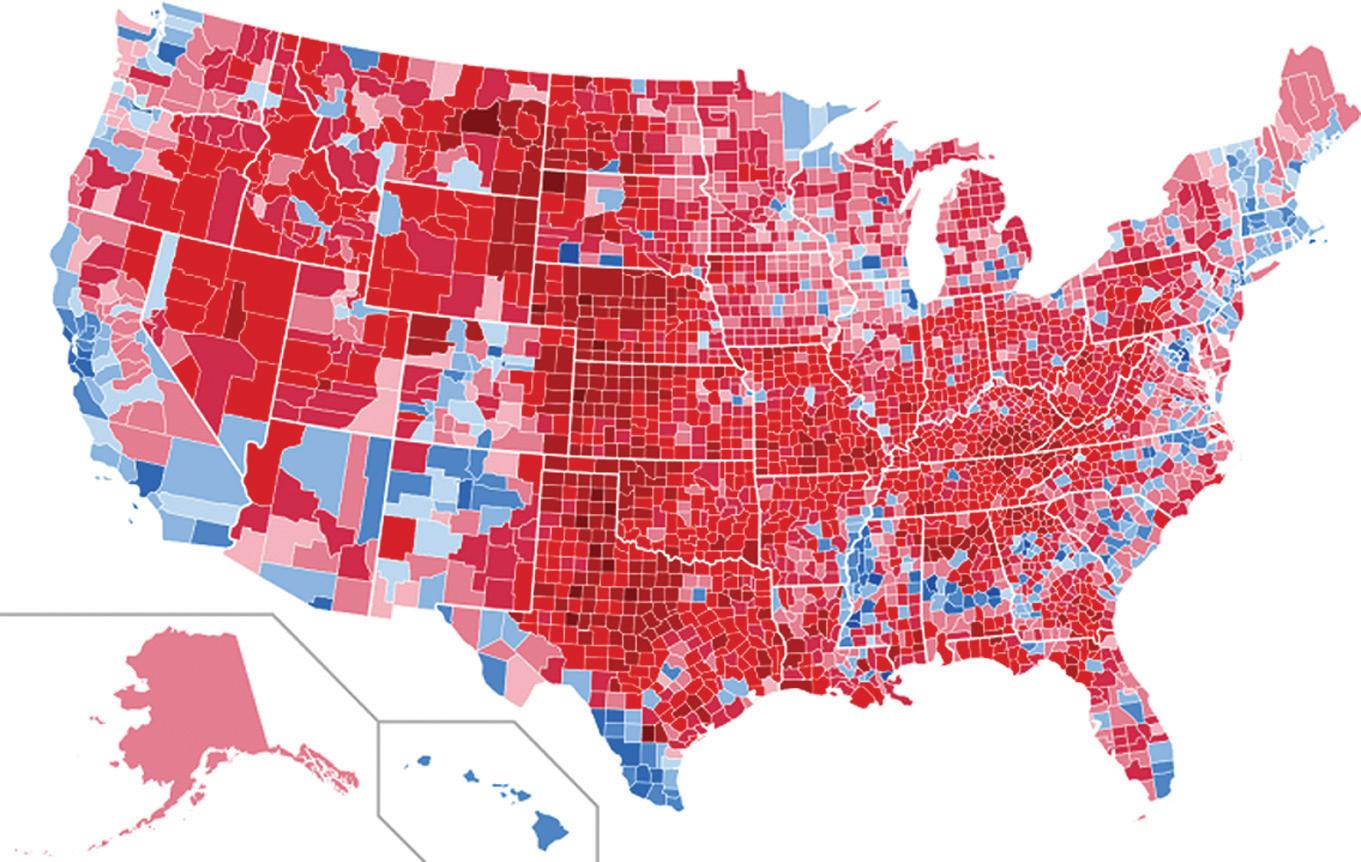

1. Map of the 2016 US presidential election, with darker blue indicating a higher percentage of votes for Democrat Hilary Clinton and darker red indicating a higher percentage of votes for Republican Donald Trump.

2. Racial segregation and 8 Mile Road, Detroit, 2011.

3. Entrance to the underground cinema at Köpi, which shows free movies twice a week, and the northeast corner of the courtyard.

4. Entrance to the old gym at Köpi, which briefly hosted Queer Wrestling Friday, as well as to Koma F (one of the main music venues), the archives and information center, and the private common areas of the Hausprojekt, including the Aquarium.

5. Köpi courtyard.

6. Residential street in Orlando West, just off Vilikazi St. The Orlando Pirates soccer field, the “Berlin Wall of Soweto,” and an Apollo surveillance light are visible in the background.

7. Street art by Julie Lovelace.

8. Street art by Afrika 47.

9. Panels south of Main Street by Tyke, Mars, and TapZ.

10. Work by Rasty to the left of Tyke’s work. Hijacked building with the telltale signage in the background.

11. Rigaer 78, former squat and current Hausprojekt and music venue in Friedrichshain.

12. Alley to a Hausprojekt courtyard on Kastinallee.

Text Photos

1.1. My home office. 28

2.1. Street art in the Smoketown neighborhood of Louisville, Kentucky. 61

2.2. (a) La République, Paris. (b) Robert E. Lee, Richmond, Virginia. 80

2.3. Michael Jackson memorial, Munich. 81

3.1. Ellington memorial and traditional facade in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, DC. 100

3.2. The same place shown in Figure 3.1, one year later. 100

3.3. The main strip of Columbia Heights on 14th Street after the 1968 riots. 102

3.4. The same block shown in Figure 3.4, in 2019. 103

3.5. Harriet Tubman Field, with the school and traditional Columbia Heights architecture in the background. 109

5.1. Altbau apartment buildings in Wedding. 141

5.2. Decorated exposed Altbau wall with art by ROA, Berlin Kidz, and others. 146

5.3. Berlin Wall next to Köpenicker Straße, 1983. 148

5.4. The Spree near Schillingbrücke, looking north into East Berlin, the Wall, and the checkpoint, September 1990. 149

5.5. The Spree near Schillingbrücke, same view as in Figure 5.4, July 2018. 149

5.6. “Shackled by Time” and “Take Off That Mask,” Blu. 151

5.7. Blacked-out art, with ads for the planned condos in view next to the construction site. 152

5.8. Men urinating on Curvystraße. 153

5.9. Köpi soon after its occupation, early 1990s. 158

5.10. The fence outside of Köpi. 162

5.11. Main entrance to Köpi. 163

5.12. Köpi Bleibt. Edge of the west wing of the building. 168

5.13. Visiting dignitaries arrive at Tempelhof, 1954. 172

5.14. Community garden at Tempelhof. 174

5.15. Abandoned wing of the Tempelhof Terminal. 175

5.16. Nazi bomb shelter under Tempelhof, with paintings for children on the wall. 176

5.17. Syrian refugee settlement with the children’s circus behind it, photographed from Tempelhof Airport. 177

5.18. The Karstadt during the 1930s. 180

5.19. Roof of the Karstadt.

180

5.20. Crowds talking to visiting reporters near the bombed ruins of the Karstadt. 181

5.21. Life against the Wall in Neukölln, a few blocks east of Hermannplatz, 1970s. 182

5.22. May Day demonstration at Hermannplatz, 1970s. The sign reads, “Only under socialism do artists have equal rights and are they beneficiaries of all social and cultural achievements.”

184

5.23. Free Syria rally at Hermannplatz. 188

5.24. Checkpoint Charlie, leaving the American sector, 1980. 190

5.25. The same view of Checkpoint Charlie as in Figure 5.24, but in 2018. 190

5.26. Cosplaying tourists and fake guards at “Checkpoint Charlie.” 191

5.27. Displaced bits of the Wall for sale in the Mauermuseum gift shop. 192

5.28. Copies of the American Sector sign for sale in the Mauermuseum gift shop. 192

6.1. Hijacked buildings in Hillbrow, as seen from Constitution Hill. 213

6.2. Ponte City Apartments, Berea, 2017. 217

6.3. Workers removing garbage from the center of Ponte City in 2003. 218

6.4. Rockey Street, Yeoville, 1985.

6.5. Raleigh St., Yeoville, early evening. 222

6.6. Chef Sanza at work in his kitchen in the Yeoville Dinner Club, Rockey Street. 225

6.7. Solitary confinement cell in Section 4, 2018. 229

6.8. Great African Staircase at Constitution Hill. 231

6.9. The informal economy and the monetization of space in Orlando West, Soweto. 235

6.10. The Orlando squatters’ camp, 1951. 236

6.11. Soweto uprising in Orlando West, June 16, 1976. 237

6.12. Bank City shops, near Jeppes and Simmonds Streets. 241

6.13. Jeppestown, 1950s, on the edge of what is now Maboneng Precinct on Main Street. 243

6.14. Fox Street in Maboneng on a Sunday afternoon. 245

6.15. Outdoor boxing gym on Beacon Street in Maboneng Precinct, with Kombis in the background. 246

6.16. Intimate stenciling in Maboneng. 252

6.17. Looting and protesting of Maboneng in Jeppestown by Zulu residents, 2015. 253

7.1. Teepeeland. 280

7.2. Blurred squats and Hausprojekte in Friedrichshain. 282

Acknowledgments

I could not have written this book without enormous help from all sorts of people and places. My largest debt is to the cities that most closely informed my research and taught me their ways, especially Berlin, Johannesburg, Soweto, New York, and Washington, DC. These cities invited me in and allowed me to explore and learn from them. Without them, and other cities that I have explored and inhabited, there would be nothing but abstractions in this book.

My son, Eli Kukla, contributed so much to this project that it could not have existed without him. He served as my research assistant for all of my fieldwork. Because of his extraordinary facility with languages, his official job was to help with communication in German and Arabic (and, as it turned out, Zulu, which he picked up quickly), as well as to translate documents, help with archival research, and identify languages used in different sites. But in fact, his role became much more extensive. He helped me choose and interpret research sites and accompanied me on nearly all of my research outings. Perhaps most important, he discussed each part of our experience with me endlessly and helped me interpret what we saw. He read drafts of multiple sections and gave me helpful comments. In short, he participated in almost every stage of the research and writing process, in ways that far exceeded his official assistantship responsibilities. He has put literally hundreds of hours into this project. Although all the text here is my own, he contributed so much by way of both labor and ideas to this book that he almost counts as a coauthor.

My next debt is to Marianna Pavlovskaya. When I began working in earnest on this book, drawing only on my background as a philosopher and my enormous and passionate love of cities, I quickly came to realize that I needed a grounded empirical understanding of how cities developed and worked in order to complete the book responsibly. I decided to go back to school and get a master’s degree in urban geography from CUNY-Hunter College. Marianna Pavlovskaya took me on as an advisee and mentored my master’s thesis, “Repurposed Spaces in Berlin and Johannesburg,” which formed the basis for Chapters 4, 5, and 6 of this book. I could have not had

a better adviser; she is a brilliant geographer who was willing to both share her wisdom with me and take me seriously as an odd colleague-student hybrid. I thank her for taking on such a quirky project and advisee; for being so supportive and insightful in her advice; for letting me work independently when I wanted to; and most of all, for doing more than anyone else to help me make the paradigm shift from thinking like a philosopher to thinking like a geographer, or at least a philosopher-geographer. Her intellectual example and mentorship have been invaluable. Indeed, my time at Hunter was a midcareer gift. The intellectual training, stimulation, and inspiration I received there were pivotal for getting me through this project. I am grateful as well to my other professors in the program, particularly Inez Miyares and Rosalie Ray, whose seminars also had a hand in shaping this book, and to Jillian Schwedler, who served as the second reader on my thesis and whose work on repurposed space inspired my own.

My third debt goes to my wise and forbearing editor at Oxford University Press, Lucy Randall, who both supported and believed in this unusual interdisciplinary project and showed unlimited patience with my ever-extending timeline, which kept stretching to incorporate new degrees, new fieldwork, and several changes in direction in my writing.

I am incredibly grateful to multiple exceptionally educated, knowledgeable, and committed tour guides, archivists, and other residents with special geographic knowledge in Washington, DC, Berlin, Johannesburg, and Soweto, who got excited about my project and ended up helping me with my research in ways that went far beyond their job descriptions. With their help, I found and accessed spaces I never would have otherwise known about, made invaluable connections, and got a deep and rich feel for the cities. These were people who love and understand their cities, and were willing and able to share that love and understanding; their generosity and knowledgeability were remarkable. My colleague and friend Olúfẹ mi O. Táíwò allowed me to interview him in depth about the racial micropolitics of a playing field in Columbia Heights, Washington, DC. Maria Klechevskaya of Berlin ended up redirecting my approach to finding research sites. Julia Dilger, the archivist at the Neukölln Museum in Berlin, spent an entire day helping me find treasures in her collection. Natalia Albizu let me interview her in depth about life in Neukölln. I am especially honored and grateful that the residents of Köpi 137 decided to allow me to do research and take photographs in their home, despite their commitment to privacy. In particular, I thank Köpi spokespeople Frank and Gabby

for their generosity in showing me around the Hausprojekt and talking to me in depth about its history, values, and norms. In Johannesburg, I owe gratitude to Nicholas Bauer, Bijou Dibu, Grant Ngcobo, and the entire staff of the Dlala Nje nonprofit organization, which is dedicated to fostering a rich understanding of inner-city Johannesburg as a route to social justice and community empowerment. Johannesburg street art anthropologist Jo Buitendach, who runs the educational tour company and urban outreach organization P.A.S.T. Experiences, helped me see the city in a whole new way. In Soweto, I learned so much from Ntsiki Sibusiso Ntombela, who not only helped me explore parts of the township that I never would have found, but spent many hours giving me textured social context and background knowledge of the region.

I am enormously grateful to the Society of Women Geographers, which gave me a research award that funded the second phase of my fieldwork, and to Georgetown University, for giving me a Senior Faculty Research Award, a Summer Research Award, and a sabbatical, all of which added up to a full year of protected research time that I spent on this book.

I have had endless helpful conversations about cities with numerous friends and colleagues over the years. I am grateful to everyone who sent me articles, maps, and graphs, and who was willing to let me talk endlessly about cities with them. I particularly benefited from conversations with Zed Adams, Kenny Easwaran, Carolina Flores, Cassie Herbert, Bryce Huebner, Thi Nguyen, Joseph Rouse, Daniel Steinberg, and Ronald Sundstrom. Kenny Easwaran provided absolutely invaluable comments on the entire manuscript. I am grateful also to audiences at Hunter College, the American Society for Aesthetics, the Pacific and Eastern meetings of the American Philosophical Association, the Philosophy Department at the University of Johannesburg, the Berlin chapter of Minorities and Philosophy, a workshop on the work of Joseph Rouse at Frei Universität Berlin, the Society for Philosophy of the City, and the Washington, DC, Humanities Festival for the chance to discuss ideas in this book and for helpful feedback.

I am grateful to my partner and true love, Daniel Steinberg, not only for being the best and most patient conversationalist, but also for making it possible for me to spend half my time in New York as a student for two years, plus months at a stretch in Berlin and Johannesburg, just because I was excited about this project and enjoying my research. He did endless extra dog walks and grocery trips and put up with way too many nights alone. I will always appreciate the momentousness of this gift he gave me.

Introduction

The world is urbanizing. As of 2018, urban space took up about 1% of the earth’s land and accounted for 55% of the world’s population, according to the United Nations, and the latter figure is projected to rise to 68% by 2050. According to some measurement methods, 85% of the world’s people now live in urban areas. Fifty years ago, only 33% of the world’s population lived in cities, and city dwellers numbered one billion, compared with four billion now.1 As the world urbanizes, cities are also changing. No longer centers of manufacturing, they are transforming into globalized hubs for communication and coordination (Smith 2002). Gentrification in many cities has reversed their mid-twentieth-century structure, and city centers have become coveted by those with money.

In a world that seems to be entering a period of extreme civil division around the globe, cities are also increasingly important as the primary sites where such tensions are performed and debated. Protesters walk down main streets of cities or occupy squares in front of capitol buildings; they do not march down country roads. Cities are places to see and be seen; they are shared spaces; and accordingly, essentially, they are the places where our political disagreements are played out as spectacles.

We know that city dwellers show systematic differences from those who live elsewhere. There are countless studies documenting differences in education, attitudes, eating habits, family structures, and so forth between city dwellers and others. For example, city dwellers are consistently more tolerant of difference, less socially risk-averse, and farther politically left than suburbanites or rural dwellers. People tend to be more anti-authoritarian the closer they are to a city center (Thompson 2012). In the United States, they vote Democrat in far greater numbers, even holding race, gender, and income constant (Gainsborough 2005). On any electoral map of the US, one can spot the cities by looking for bright blue dots amidst the sea of surrounding red; cities generally vote Democrat even in states that are otherwise Republican strongholds (Color Image 1). Other countries across the globe tend to show a similar pattern (although the two-party system in the US makes the contrast especially visually stark).

City Living. Quill R Kukla, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190855369.003.0001

Thus we have good reasons to want to understand the dynamics of cities and contemporary city living. Of course, there are indefinitely many disciplinary perspectives and angles from which one can try to understand these things. The trends I just mentioned are large-scale population-level trends. At the population level, one could study cities from the perspective of health or crime, or through multiple other lenses. For example, it is wellknown that structural patterns such as the distribution of grocery stores and subway stops affect urban health outcomes and crime rates at the population level. My focus in this book is different. I am interested in how cities and city dwellers make one another, not at the level of urban policy, public health patterns, or economic dynamics, for instance, but at the scale of particular bodies making small movements through particular spaces. This book is about how busy, diverse, crowded urban spaces shape and are shaped by the residents who inhabit them. I am interested in the processes by which spaces shape the agency, behavior, and perceptions of their users, at the same time that users remake spaces in accordance with their needs.

My interest is in the smaller, more fleeting motions and interactions that make up our day when we live in a big city, and how these shape our sense of self, our judgment, and our responses in ways we may well not even notice. I will explore how our small, everyday material motions and transactions in city spaces—what I call micronegotiations play a pervasive and fundamental role in shaping our perceptual skills, our embodied habits, our sense of self and identity, and our moral judgments and risk assessments. Conversely, our practices within urban spaces remake them into niches suited to our ways of living. These effects are far from uniform: our race, class, immigration status, abilities, and gender affect how we negotiate urban spaces, while built urban environments encode and uphold (and potentially push back against) norms that sustain disadvantage and oppression. While my primary goal is not to offer prescriptive recommendations, my hope is that this book will enrich our understanding of the possibilities for change and flourishing that cities can offer, as well as the ways in which they risk enhancing and reinscribing injustice. It will illuminate what is distinctive about city living and urban civic life, and the role that cities play in the identities and moral agency of their residents.

This is a fundamentally interdisciplinary book. I drew on methods and disciplinary tools where I found them. My research methods included phenomenological and conceptual analysis, and my own ethnographic fieldwork and archival research. I used literature from philosophy, urban

geography, humanistic geography, history, architectural theory, urban planning, art theory, biology, sociology, and anthropology. I documented sites with photographs, videos, and a diary, but also talked to residents in the cities I studied who had expertise in local history, politics, and street art.

My primary theoretical approach was grounded in a combination of philosophical phenomenology and the humanistic tradition in geography, which seeks to ‘read’ human and cultural phenomena through the lens of spatiality, and in turn takes spatiality to be fundamentally constituted by human place-making. For geographers, human experience and behavior and social patterns are inherently spatially embodied and located, as well as indexed to different scales, and this spatiality is the privileged theoretical tool for understanding them. Within that, for humanistic geographers, these embodied spatial locations and scales are best understood as places, whose identity can be understood only with reference to how they are experienced and used by their dwellers, and whose character is produced in part by meaningful human activity. Places and spatiality, in this tradition, are infused with interpretable meanings that both shape and are shaped by how their inhabitants use and experience them.2 I wanted to explore the living uses and experiences of cities by understanding them as places structured by their spatiality. My spatial analyses are readings of interpretable, meaningful places, as opposed to, for instance, quantitative analyses of measurable spatial patterns. Unlike most humanistic geographers and phenomenologists, however, I am less interested in individual subjective experiences of place than in the materiality of spaces and their embodied uses. My goal was to read urban spaces as saturated with meaning, but ‘meaning’ for me is not about individual psychological contents or reactions but rather about how a space functions to support certain kinds of agency, power relations, cultural patterns, and the like.

I will argue that people’s uses of space and the impact of space on people together create new, real, concrete things that would not exist outside of that ecological context. Through our micronegotiations as we move through space, we produce what I call ecological ontologies: sets of real, concrete things and events that can exist only within an ecological system, made up of a material space and its users in dynamic interaction with one another. Rush hours, borders between neighborhoods, entertainment districts, and gang territories are all examples of perfectly real things that exist only in cities, in virtue of dwellers using spaces in specific ways. I will explore the ecological ontologies of cities and smaller urban spaces. I am especially interested in the ecological ontology of territories. I will explore

how territories and their boundaries, which establish insiders, outsiders, and norms for the appropriate use of spaces by insiders, are established through micronegotiations.

Urban spaces are distinguished from one another in part by how they support and are carved out by what David Seamon calls “place ballets,” which he says generate and are constrained by “place identity.” Place ballets are spatially located bodily routines we practice, alone and together. Consider how a group of friends sit and interact together at a familiar coffee shop— how they slouch in their chairs, lean forward to talk, sip their coffee, take the same seat each time, hail the waiter, and so on. This is a place ballet: a set of movements inextricably embedded within a particular material space, with social meaning. Or to use an example of Seamon’s, consider how a worker at a grocery store moves through the aisles, arranging the food. In a place ballet, movements flow together in ways essentially supported by and integrated with a material place. Markets, train stations, and schoolyards would all be examples of places characterized by distinctive place ballets and as supporting place identities. Places constrain and give shape to place ballets, while smooth and well-choreographed place ballets produce organic and integrated places; they help give places their distinctive feel. In this book, I will explore urban spaces in significant part by unpacking the place ballets that characterize them, and figuring out how these place ballets and places arose together, and what sorts of ecological ontologies they depend upon and generate.

Urban spaces are, overwhelmingly, shared spaces. We not only use them; we use them together with others, including strangers and those whose spatial needs and desires are different from our own. Cities contain a wide variety of spaces that we share in different ways, as we will see. Cities and city spaces are distinctively and busily intersubjective; it’s not just that they contain a lot of people at once, although this is true too, but that we use these spaces jointly and negotiate them together, sometimes conflictually and sometimes harmoniously. The spaces themselves shape the intersubjective interactions that happen within them. As Susan Bickford puts it, “From Bentham to Foucault and beyond, social theorists have recognized the role of architecture in constructing subjectivity. But the built environment also constructs intersubjectivity” (2000, 356).

There are many ways of doing things with others in space. Think about various ways in which you can take a walk, and the differences in how your body moves and interacts with its surroundings in different cases. You might:

1. Take a walk by yourself in an isolated area, setting your own pace, letting the landscape and your own goals dictate how fast you move and by what path, letting your gaze and attention be drawn entirely by the landscape.

2. Take a walk with a friend, which involves calibrating your pace to theirs. You may each need to slow down or speed up to keep your paces matched. You will negotiate together, usually implicitly, what’s worth stopping and looking at, how fast to go, and which path to take.3

3. Take a walk among strangers in a crowded city. You again need to calibrate your pace, but now the goal is the opposite; walking exactly at pace with a stranger is creepy, so you will slow down or speed up as needed to stay out of sync with others. You will also be negotiating appropriate personal space and eye contact. You may need to implicitly work out how to take turns, for instance if you are passing someone in a narrow passage. You may be casually friendly toward those you pass, particularly if your attention has been caught by the same thing, for instance if you both pause to look at a piece of street art or notice together that a bus is delayed. But there are definite limits to how extended and friendly such an interaction will be, and you need to negotiate and respect these limits together.

4. Take a walk through your own familiar neighborhood. Here you are not walking with others, but you are walking among people who may be familiar to you, and you will all have a shared sense of the shape and pace of the space. You might have more extended interactions as you go; for example, you might stop for a couple of minutes in front of a new restaurant that just opened to discuss it with a neighbor, or you may stop a neighbor to ask to pet their dog. The assumed shared background here is greater than it is in the walk amidst a crowd of strangers, but it would still be odd for you to match your pace with that of a neighbor also out for a walk or for you to ask them to slow down so you can keep up.

5. Take a walk in a foreign city that is new to you. You aren’t sure of directions, or local customs, or norms for communicating and interacting. Now you won’t have that same expertly embodied set of skills available to you. You will probably have to consciously control and adjust your pace, perhaps dodging unexpected obstacles or vehicles. (Whenever I talk about this, I am reminded of the time that I was almost run down by a giant tricycle being ridden by about seven pre-teenagers, pulling a wheelbarrow spilling over with bleating goats,

which was barreling down a sidewalkless, one-lane street in Cairo.) You will not be certain how to pass through the subway turnstile, how to take turns, and so forth. Your interactions with strangers will likely be minimal, although your manifest incompetence may attract friendly locals, who stop and ask to help, or unfriendly locals, who may try to take advantage of you.

In each of these cases, your movement through space will be structurally different. It will be controlled in part by the space, but also by your relationship to those with whom you walk. You, the space, and your fellow walkers are in high-bandwidth interaction with one another, forming an ecosystem. The point is, there are many, deeply different ways to share space, so we have opened rather than settled questions about how urban spaces and urban dwellers make one another when we point out that urban spaces are shared. Understanding these different kinds of sharing, and how spaces and dwellers are constituted through them, is a key goal of this book.

I cannot launch into this book without pausing here in the introduction to reflect on the unprecedented moment in history at which I am finishing writing. Right now, in the spring of 2020, most of the world is in some degree of lockdown because of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Most businesses are shut; only essential workers are working outside of the home; people are under orders to stay at home as much as possible, not to gather in groups, and to wear a mask and maintain at least six feet of distance between themselves and anyone who is not a member of their household. Around the world, with the exception of a few outlier states and countries, our streets are empty, and people move as far away from one another as possible, avoiding physical interaction. Over the course of about a week in March 2020, our movement through cities and our micronegotiations and interactions changed completely; they have become minimal, fearful, tentative, and a constant matter of conscious reflection.4

In other words, movement in cities has become, at least for the moment, the opposite of what I spend this book arguing characterizes typical urban life and movement. The COVID-19 crisis has changed just about everything that I have written about here. I developed a picture of cities as defined by proximity among strangers, and shifting and fluid bodily norms for personal distance and interaction. I explored how city dwellers develop an inculcated

and unreflective sense of risk and safety that helps them move competently through space but also recreates biases. All of this has been upended. We are all exceptionally reflective as we move through space now, and the distances between us are uniform and rigidly calculated. All other people on our streets show up as immediate threats. Our embodied interactions have been reduced to almost nothing. Our sense of risk and safety has been thrown into chaos; everything seems risky and we have little to no settled or expert ability to determine how risky a situation is, not least because threats are mostly invisible.

I spend a great deal of time in this book talking about spatial agency and its importance for the flourishing of city dwellers. Spatial agency is our ability to autonomously occupy, move through, and use space, as well as our ability to mark and transform it in accordance with our needs and desires. I explore what enables and undermines spatial agency, and I try to demonstrate its importance to city dwellers. But all at once, our spatial agency has been radically diminished. Our mobility has been dramatically reduced, both at the local level and in terms of long-distance travel. In the places we are still allowed to go to, how we move through and use space is tightly controlled and surveilled. In Chapters 5 and 6, I discuss the fallout from the severe restrictions on spatial agency faced by residents in divided Berlin and apartheid South Africa. We are facing similar, and in some ways even more draconian, spatial restrictions and surveillance now, although it is at least in large part for the good cause of public health.5 So many people right now are joking about throwing themselves into home improvements; but I think there’s a deeper fact at issue here about homes being the only place we can currently exercise spatial agency (if anywhere, since many people don’t have safe homes, or any privacy or power within them, or the resources to work on them). This home-directed spatial agency is fundamentally anti-urban, and if this book is right, it is a serious hit to the conditions for our flourishing as city dwellers. Right now, in May 2020, it is too soon to tell whether this is just an aberrant phase that will go down in history as an odd time, or whether everything about how we use city space and move through and dwell in cities has changed forever and has rendered this book itself an exercise in historical documentation of what used to be. Either way, and as demoralizing as it is to have all the phenomena I have been painstakingly studying as characteristic of our way of life suddenly ripped away, I do think that one of my core theses has been proved true by this crisis: I argue that our agency and experiences are planted in space and rooted in motion; our sense of territory and place

and how we move through space are deeply constitutive of our senses of self, our agency, and our perceptual capacities. This crisis has attacked our sense of self on a fundamental level. Our cities have changed so radically and suddenly and lost so much of their bustling citylike character that they have no settled place identity, and for most of us, our normal territories outside our homes no longer feel like ours, no longer feel safe. I think an overwhelming number of city dwellers right now are feeling fundamentally disoriented; we are quite literally out of place.

Michael Kimmelman (2020) writes about the unique damage of the pandemic and how it not only harms us but undercuts our resilience in the face of harm. He points out that when we face a crisis, it is our ability to come together and act together that is most likely to enable us to repair the damage it causes. Empirically, he is right: communities survive disasters better when they have resilient social support networks, and isolation is the biggest risk factor during a crisis; social connection literally saves lives during an ecological disaster (Klinenberg 1999, Cutter et al. 2008). But the current pandemic has forced us to take the opposite approach—to stay more isolated the worse things become. Kimmelman (2020) claims that the pandemic is distinctively anti-urban. City spaces, he writes, were built to be used together, so those of us in cities are now occupying spaces maximally ill-suited to this crisis: “social distancing . . . not only runs up against our fundamental desires to interact, but also against the way we have built our cities and plazas, subways and skyscrapers. They are all designed to be occupied and animated collectively. For many urban systems to work properly, density is the goal, not the enemy.”

But this is only part of the story. In response to Kimmelman, Kevin Rogan argues in “The City and the City and Coronavirus” (2020) that as many of us mourn the loss of our urban lives, millions of urban dwellers are still forced to go to work under unsafe conditions. For many of us, who can work from home or have the means to take a break from work, suffering from isolation is itself a privilege. Rogan points out that the romantic idea that we are all suffering from loss of togetherness depends on the myth that we were together rather than separated by structural inequality to begin with. Building on Rogan’s point, not only are millions of poorer city dwellers forced to move through space even as the rest are forced to isolate at home, but bodies that do move through space still do not have equal spatial agency. Unsurprisingly, Black and Brown bodies are being differentially targeted for policing and punishment (Noor 2020). Our losses are

not the same as one another’s; there is no easy “we” in the city, despite our sharing space.

I think that both Kimmelman and Rogan are right: spatial agency in cities is deeply unequal and cities are fractured in all sorts of ways, and the pandemic has made these divisions even more vivid. But at the same time, cities are materially built on principles of proximity, shared space, and close-up interaction, and so the current moment is fundamentally anti-urban. City dwellers have no skills for navigating the kind of space we now have. We don’t know how to make eye contact, how to hold our bodies. We can avoid romanticizing ‘normal’ cities while acknowledging that city dwellers are facing an embodied existential crisis on top of the economic and health crises the pandemic has wrought.

I’ve been fascinated to hear, anecdotally, how much more dramatically city dwellers’ lives have been disrupted and fundamentally disoriented by the pandemic than have those in suburban areas. My suburban friends are frustrated that restaurants are closed, traumatized from being cut off from family and friends, and of course as economically and physically anxious as their city dwelling counterparts. But many report that ‘not much has changed’ on the streets, and that they are finding social distancing relatively easy and peaceful. Meanwhile, my city friends are overwhelmed by the changes. This makes sense. As I explore a bit in this book, suburbs are already constructed around the privatization of space. They are designed to, in effect, quarantine people in private spaces and to encourage people to use their spatial agency on their homes, which are their primary living sites. Suburban space is not designed to be shared space. Suburbanites generally move by car from home spaces to work spaces; they do not use their bodies to travel through and negotiate spaces in between. Homes in the suburbs are typically surrounded by buffers of private space in the form of lawns and are often literally fenced off; most suburbanites do not share halls, porches, and walls with others as city dwellers do. In effect, the built choreography of suburban life is a choreography of quarantine to begin with—of isolation with one’s immediate intimates. It is cities that have been suddenly robbed of their place identity. * * *

Chapter 1 lays the philosophical foundation for this book. I develop a picture of spatially embedded agency and perception, and argue that spaces and their dwellers mutually constitute one another. I also introduce the notion of an ecological ontology and explore how ontologies can be generated through

micronegotiations. This is the most abstract chapter and is not specific to urban spaces or dwellers in particular.

Chapter 2 offers a philosophical account of what is distinctive about urban spaces and urban subjectivity. City space, I argue, is distinctively shared space, characterized by proximity and unpredictability. City dwellers develop metaskills that allow them to competently navigate city spaces, and these in turn constitute their agency and their perceptual capacities. Drawing on empirical sociological literature, I explore how city dwellers see and judge risk and safety, order and disorder. I also develop the notion of an urban territory, and explore how territory is claimed, used, and bounded through bodily micronegotiations.

Chapter 3 concerns gentrification, which is one of the most important ways in which urban spaces are transforming. This chapter serves as a transition between my philosophical analysis of city spaces and dwellers in general and my empirical explorations of particular urban spaces. Gentrification interests me because it is such a widespread urban phenomenon, and one of pressing political importance. But more specifically, it is a powerful example of how dwellers and spaces change by shaping one another, and of the struggles and tensions that surround competing forms of agency that are simultaneously trying to establish territory in conflicting ways. Moreover, gentrification almost always provides us with powerful examples of power differentials between dwellers, who are unequally able to exercise spatial agency and enjoy a smooth fit between the spaces they inhabit and their own practices and needs. In keeping with the overall themes of this book, I look at gentrification through the lens of micronegotiations and movement through space. Drawing on my own fieldwork, I use Columbia Heights, a neighborhood of Washington, DC, as a case study.

Chapters 4, 5, and 6 go together. In Chapter 4, I introduce my notion of a repurposed city. A repurposed city is one that was built to support one form of economic, social, and political relations—a form which has now collapsed, so that the city has to accommodate radically new uses, users, and purposes; in turn, residents have to find ways of using and adapting a material city built for something quite different. In repurposed cities, new dwellers must find ways of tinkering with urban spaces and reinvesting them with new meanings in order to use them in new ways. Their uses are constrained by the material forms of the past order, while conversely, they creatively remake those forms.

In Chapters 5 and 6, I draw on my own fieldwork and archival and historical research in order to explore the repurposed cities of Berlin and Johannesburg, respectively. Cold War Berlin and apartheid Johannesburg were both extreme examples of cities in which the material space was designed to support and enforce a specific social order, including specific forms of control and surveillance over how people used and moved through space. Both orders collapsed at almost the same time, and both cities are now occupied by very different people with different forms of life, who need to use the found space of the city in new ways. I examine both cities by exploring a set of small repurposed spaces within each, comparing their present and past uses and meanings, and situating them within the history and spatial logic of each city. I spend a great deal of time on repurposed cities, because they are especially vivid lenses through which we can see the mutual constitution of dwellers and spaces in action. I examine how repurposed urban spaces function, and sometimes fail to function, as dynamic, integrated places whose parts are mutually constitutive in the way I have described. My hypothesis going into my fieldwork was that repurposed cities would throw these mutually constitutive processes into especially sharp and interesting relief. In regular, functional spaces, the match between agents and spaces is typically seamless enough to just recede into the background, and their mutual constitution can be harder to see. I was interested in looking at cities where there would be no such seamless fit—cities in which people would be actively negotiating and working on spaces, and spaces would be visibly imposing themselves on agents.

Finally, Chapter 7 takes a more explicitly normative turn. I argue that inclusion in a city or neighborhood requires more than the right to physically reside in it; it requires what Henri LeFebvre, Don Mitchell, and others have called the “right to the city.” The right to the city is not just a formal right to be inside of a city without being thrown out; it should be conceived, I argue, as a right to inhabit the city. This requires that we have voice and authority within a city; that we be able to participate in tinkering with it and remaking it; and that we belong in it rather than just perch in it. I explore the complex relationships between public spaces, inclusive spaces, and the right to the city. I ask what sorts of spaces city dwellers need in order to have a flourishing urban life and to exercise their spatial agency. I examine some of the barriers to being included in urban spaces that different kinds of bodies face, and think about what it would take to build a more just and inclusive city.

Guide for Readers

As the author of this book, I am of course attached to all of its chapters and believe they all support and depend on one another in various ways. That said, different kinds of readers with different interests and disciplinary backgrounds could read more selectively.

• Philosophers whose primary interests are conceptual rather than empirical could read Chapters 1, 2, and 7 as a short philosophical book on spatially embedded agency and the mutual constitution of cities and their dwellers.

• Readers with primarily normative interests in urban space, spatial justice, and the right to the city could read Chapters 2, 3, and 7.

• This work could also be read as a short book on repurposed cities, with Chapter 1 as philosophical background and framing, followed by Chapters 4, 5, and 6.

• Readers with specific interests in the city of Berlin or the Cold War could read only Chapters 4 and 5, while readers with specific interests in the city of Johannesburg or apartheid could read only Chapters 4 and 6.

Color Image 1. Map of the 2016 US presidential election, with darker blue indicating a higher percentage of votes for Democrat Hilary Clinton and darker red indicating a higher percentage of votes for Republican Donald Trump.

Color Image 2. Racial segregation and 8 Mile Road, Detroit, 2011. From demographics.virginia.edu/DotMap.