Cicero:PoliticalPhilosophy(FoundersofModern PoliticalandSocialThought)MalcolmSchofield

https://ebookmass.com/product/cicero-political-philosophyfounders-of-modern-political-and-social-thought-malcolmschofield/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Useful Enemies: Islam and the Ottoman Empire in Western Political Thought, 1450–1750 Noel Malcolm

https://ebookmass.com/product/useful-enemies-islam-and-the-ottomanempire-in-western-political-thought-1450-1750-noel-malcolm/

ebookmass.com

The Political Thought of David Hume: The Origins of Liberalism and the Modern Political Imagination 1st Edition Zubia

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-political-thought-of-david-hume-theorigins-of-liberalism-and-the-modern-political-imagination-1stedition-zubia/

ebookmass.com

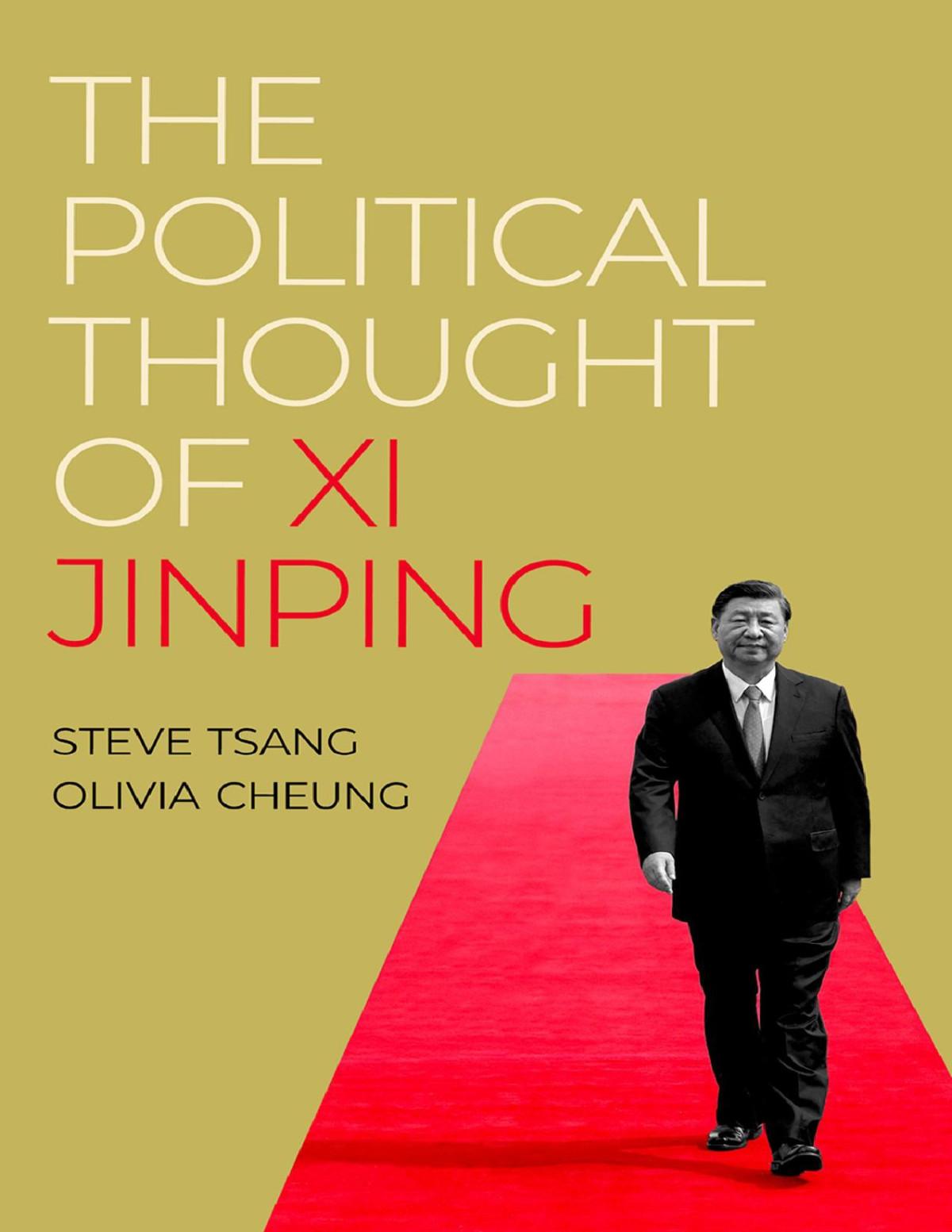

The Political Thought of Xi Jinping Tsang

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-political-thought-of-xi-jinpingtsang/ ebookmass.com

The Sisters Café Carolyn Brown

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-sisters-cafe-carolyn-brown-3/

ebookmass.com

Kinn's The Clinical Medical Assistant: An Applied Learning Approach 13th Edition

Deborah B. Proctor

https://ebookmass.com/product/kinns-the-clinical-medical-assistant-anapplied-learning-approach-13th-edition-deborah-b-proctor/

ebookmass.com

Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering 7th Edition William F. Smith Professor

https://ebookmass.com/product/foundations-of-materials-science-andengineering-7th-edition-william-f-smith-professor/

ebookmass.com

HQ Solutions: Resource for the Healthcare Quality Professional (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/hq-solutions-resource-for-thehealthcare-quality-professional-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

Bipolar Disorder For Dummies. 4th Edition Candida Fink

https://ebookmass.com/product/bipolar-disorder-for-dummies-4thedition-candida-fink/

ebookmass.com

The Perfect Mistake (The Connovan Chronicles Book 2) Olivia Hayle

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-perfect-mistake-the-connovanchronicles-book-2-olivia-hayle/

ebookmass.com

Developing Web Components with Svelte: Building a Library of Reusable UI Components 1st Edition Alex Libby

https://ebookmass.com/product/developing-web-components-with-sveltebuilding-a-library-of-reusable-ui-components-1st-edition-alex-libby/

ebookmass.com

FoundersofModernPolitical andSocialThought

CICE R O

FOUNDERSOFMODERNPOLITICALANDSOCIALTHOUGHT

SERIESEDITOR

MarkPhilp

UniversityofWarwick

The Founders seriespresentscriticalexaminationsoftheworkofmajorpolitical philosophersandsocialtheorists,assessingboththeirinitialcontributionandtheir continuingrelevancetopoliticsandsociety.Eachvolumeprovidesaclear,accessible, historicallyinformedaccountofathinker’swork,focusingonareassessmentofthe centralideasandarguments.Theseriesencouragesscholarsandstudentstolinktheir studyofclassictextstocurrentdebatesinpoliticalphilosophyandsocialtheory.

Publishedintheseries:

JOHNFINNIS: Aquinas

GIANFRANCOPOGGI: Durkheim

MAURIZIOVIROLI: Machiavelli

CHERYLWELCH: DeTocqueville

RICHARDKRAUT: Aristotle

MALCOLMSCHOFIELD: Plato

JOSHUACOHEN: Rousseau

FREDERICKROSEN: Mill

MALCOLMSCHOFIELD: Cicero

Cicero PoliticalPhilosophy

MalcolmSchofield

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford, OXDP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©MalcolmSchofield

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted

FirstEditionpublishedin

Impression:

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttothe RightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY ,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:

DOI:

PrintedandboundinGreatBritainby ClaysLtd,ElcografS.p.A.

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

fin

InmemoryofMiriamGrif

Preface

ThisbookexplorestheCicerowhowroteofhis ‘incredibleandunparalleled loveforthe respublica’ (deOr. .).Hisworkinpoliticalphilosophystands asthe firstsurvivingattempttoarticulateaholisticrationaleforrepublicanismandasustainedaccountofitsdifferentelements.Thesemightbe summarizedinwordsofMarkPhilp,generaleditoroftheseriesinwhich thisbookappears:1

Itakerepublicanthoughttosharethreedistinctivefeatures:thatpoliticalorderand stabilityrestsultimatelyonsustainingthecivicvirtueofthecitizensofthestate;that theendofpoliticsisthecommongoodofthecitizens;andthattheachievementof civicvirtueandthecommongoodisafragileachievementforwhichthereare certainsocial,material,cultural,and,aboveall,institutionalprerequisites.

InthisstudyCicero’spioneeringcontributiontothatkindofrepublican thoughtistrackedthroughstudiesofsomeofhismajorthemes,which includesomethatstillhaveresonancestodayasinearlierperiodsofthe historyoftheWest.Thebookfocusesmainlyonthethreemajorwritings thathedevotedtopoliticalphilosophy: Onthecommonwealth, Onlaws,and Onduties thethirdoftheseformallyspeakingageneraltreatiseonpractical ethics,butinrealityaddressedtotheyoungmanexpectedandexpectingto enterpubliclife,andmuchofitconcentratingonconductinthepublic sphere.

Cicerohimselfplayedasignificantpartasaleading figureintheturbulent politicsofthelasttwoorthreedecadesofthe Roman Republic,notleast throughhisoratory.Thepoliticalandethicalstanceshetakesinhisspeeches areintimatelyrelatedtohisofficialtheorizing.Thesameistrueofhis correspondencewithfriendsandacquaintanceswhenhediscussespressing politicalissuesorquestionsofcharacterorbehaviour.Treatmentofmaterial inlettersandspeechesaccordingly figuresstronglyinsomechapters.Thereis quitealotofhistoryandhistoricalcontextintheirpages(myapproachto Cicero’spoliticalphilosophizingis,Ithink,broadlyinlinewiththe ‘Cambridge’ styleassociatedparticularlywiththenameofQuentinSkinner). Ihaveattempted,ofteninthefootnotes,togivesomeideaofthestateof

controversyaboutinterpretationofthehistory,sofarasithaspresenteditself tomeinmyowninevitablyselectiveandunsystematicreadingofthetruly massiveamountofpublicationdevotedtoit.

AllthreeofthemajortheoreticalworksareaccessibleingoodEnglish translations.Thebookdoesnotattemptcomprehensivecoverageoftheir contents,norofalltheveryextensivescholarshiprelevanttothemortothe particularthemesselectedfordiscussion.Thedialogues Onthecommonwealth and Onlaws,inparticular,arehighlycraftedandoftensubtlepiecesof writing,asareCicero’sletters(Onduties strikesmeasonthewholemore straightforward,althoughlesssoinBook andinotherpassageswherewe knowormaysuspectthatCiceroisnotfollowingmoreorlesscloselyhis GreekmodelPanaetius).Ihaveattemptedtocommunicatesomesenseof thisinmydiscussionsandinsomeofthetranslationsfromtheoriginalLatin (andoccasionallyGreek),whicharemyownunlessotherwiseindicated. Thebookdoesaimtogivereadersafeelforwhatonemightcallthe Ciceronianstateofplay,andthroughreferencestothebibliographyto supplysomeguidanceonhowthatmightbefollowedup.Butitdoesnot presupposemuchpriorfamiliaritywithCiceroor Romanhistory,nor knowledgeofLatinvocabulary.Translationsofparticulartermsareprovided whentheymaketheirinitialappearanceinthetext,andasmaybehelpfulat otherjunctures.Abbreviationsinreferencestoclassicalauthorsandtheir worksingeneralfollowthoseusedinthefourtheditionof TheOxford ClassicalDictionary (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress, ).

TheideaforthisbookwasconceivedwhenIrespondedtoaninvitation fromtheUniversityofOxfordtogiveCarlyleLecturesonthehistoryof politicalthought.Likethelectures,itisdesignedtobeofinterestbothto thoseconcernedwiththehistoryofWesternpoliticalthoughtwhowould appreciateanassessmentofCicero’scontributiontotheirdiscourse,andto studentsandscholarsofCiceroinparticularandthehistory,literature,and especiallyphilosophyoftheancientWesternworldmoregenerally.The materialitpresentsismuchdevelopedfromthelectures,butitretainstheir overallscopeandtrajectory,whicharebrieflysketchedinsection of Chapter .IhavebeenworkingandgivingtalksonCiceroformany years,andhavebenefitedfrommanycommentsbycolleaguesanddiscussionswiththem.IamgratefultoMargaretAtkinsforhelpfulcriticismsofmy firstdraftoftheIntroduction,andtoMarkPhilpandananonymousreader forthePressforsomemostthoughtfulcommentsonmy finaldraft.Iam

particularlyindebtedtoMarkandtoPeterMomtchiloffatOUPfortheir encouragementandpatiencewithmyslowprogress.Ithasbeenmygood fortunetoworksincethenwithJayashreeThirumaran,assistedbyPhil Dinesascopyeditorandothercolleagues,whohastakenmymanuscript fromsubmissionthroughtopublicationwithexemplaryefficiencyand friendlycourtesy.ThelecturesthemselvesweredeliveredinHilaryTerm, .MythanksgototheCarlylecommitteeforthehonouroftheir invitation,andparticularlytotheirchairman,GeorgeGarnett,forhishelpfulnessthroughoutandforthegenerosityofhishospitality.Itisapleasure onceagaintothanktheWardenandFellowsofAllSoulsCollegefor accommodatingmemostcomfortably,forthewarmthofthewelcomeat theirtable,andforsomestimulatingdiscussions.ManyOxfordfriendsand colleaguesshoweredmewiththeirowninvitations.

Thebookisdedicatedtothememoryofonesuch.Itisfromherthat Ihavelearnedmostaboutitssubjectandaboutthewaysinwhichthatmight profitablybetackled.Intheprologuetoherownposthumouslypublished collectedpapers,shewroteofherdeterminationfromtheoutsettostraddle ancienthistory,literature,andphilosophyinherresearch.2 IhopeIhave beenableinmyownfashiontofollowherexample.

MS

Cambridge,February

Notes

.Philp : –. .Griffin :vii.

Acknowledgements

Materialusedoradaptedfrompreviouspublicationsofmineappeared originallyasfollows:

Chapter : ‘Cicero’sdefinitionof respublica’,inJ.G.F.Powell(ed.), Cicerothe Philosopher.Oxford:ClarendonPress, –.Publishedin

‘Liberty,equality,andauthority:apoliticaldiscourseinthelater Roman Republic’,inD.Hammer(ed.), ACompaniontoGreekDemocracyandthe Roman Republic.Chichester:Wiley-Blackwell, –.Publishedin .

Chapter : ‘Cosmopolitanism,imperialism,andjusticeinCicero’ s Republic and Laws’ , HistoryofPoliticalThought.Net : –.Publishedin

Chapter : ‘Republicanvirtues’,in R.Balot(ed.), TheBlackwellCompanionto Greekand RomanPoliticalThought.Oxford:Wiley-Blackwell, –. Publishedin .

‘Thefourthvirtue’,inW.Nicgorski(ed.), Cicero’sPracticalPhilosophy.Notre Dame,Indiana:UniversityofNotreDamePress, –.Publishedin .

Chapter : ‘Debateorguidance?Ciceroonphilosophy’,inF.Leigh(ed.), ThemesinPlato,Aristotle,andHellenisticPhilosophy:KeelingLectures – London: BICS Supplement .Publishedin Iamgratefulforpermissiontoreusepassagesfromthesearticles.

Contents

.Introduction:Contexts

.CicerointheWesterntradition

.Abrieflife

Rehabilitation

.Writingpoliticalphilosophy

.Prospect

.Liberty,Equality,andPopularSovereignty

. Libertas in Romanpoliticaldiscourse

.Senateandpeople

.Libertyandequality

.Equalityandlibertyin Onthecommonwealth

.Popularsovereignty

.Government

. Onthecommonwealth

.Theconsensusofjustice

.Kingship,aristocracy,popularrule:theirdrawbacks

.Consiliumandpoliticalstability

.Historyandtheory

.Crisisandleadership

. Onlaws

.Conclusion

.Cosmopolitanism,Imperialism,andtheIdeaofLaw

.Cosmopolitanism

.Cicero’sconceptionoflaw

.Thelawcode

.Laws ‘forallgoodandstablenations’

.Justiceandimperialism

.Conclusion

. RepublicanVirtues

.Civicvirtue

. Romanvirtues

.Justice

. Magnitudoanimi

Verecundia

.Therepublicancitizen

. RepublicanDecision-making

.Citizendecision

.Principles,rules,andthecasuistryofexceptions

.Civilwar

.Tyranny

.Friendship

.Tyrannicide

.Epilogue:PhilosophicalDebateandNormativeTheory

.Introduction

.Silencingdebate

.Full-throttleddebate

.Finalthoughts

Bibliography

IndexofPassages

GeneralIndex

Introduction:Contexts

.CicerointheWesterntradition

InapproachingCicero’spoliticalphilosophy,itmayparadoxicallybehelpful tobeginwithsomeonewhotookadistinctlyjaundicedviewofwhatCicero stoodfor butatthesametimetherebytestifiestohismassivehistorical importance.ThethinkerinquestionisThomasHobbes,whointhetwelfth chapterof deCive mountsaforthrightattackonthe ‘seditiousdoctrine’ that ‘TyrannicideisLawfull’.Infact,hesays,thatputsthepositionhehasinhis sightstooweakly: ‘Nay,atthisdayitisbymanyDivines,asofolditwasby allthePhilosophers,Plato,Aristotle,Cicero,Seneca,Plutarch,andtherest ofthemaintainersoftheGreek,and RomanAnarchies,heldnotonlylawful, butevenworthyofthegreatestpraise.’ WhetherHobbescouldhavecited chapterandverseforhisclaimsofarasitrelatestoPlatoorAristotlemaybe doubted:thetormentstyrantssufferinthejustpunishmenttowhichthey aresubjectedintheafterlifearewhatwemaymostvividlyrecallfromPlato, forexample.1 Plutarchdoesseemtotakeitforgrantedthattyrannicideis somethingadmirable,withoutarticulatinganyprincipledstanceontheissue (so,forexample, Phil. –).AsforSeneca,however,thereisthepassagein whichhecriticizesMarcusBrutus’sassassinationofJuliusCaesaras ‘contrary toStoicteaching,becausehefearedthenameofking’—when ‘thebestform ofgovernmentisunderajustking’ (Ben. .).

ButforCiceroHobbesisspoton.Inthe deOfficiis (Onduties),awork whichfromthetwelfthcentury AD onwardshadentered ‘thebloodstreamof Westernculture’ , 2 tobereadinHobbes’ timeandformanydecadesprior andsubsequentlybyeverywell-educatedperson,Ciceroarguesthatassassinatingatyrantisanhonourableact,notcontrarytonature,andindeeda positiveduty.Thehealthofthebodyasawholesometimesrequiresthe amputationoflimbsthathavestartedtodeadenandareharmingtheother parts.Inthesameway,thesavageryandmonstrousbestialityofthetyranthas

toberemovedfromthebody(sotospeak)thatweareallpartofashumans (Off. .).ThatargumentwouldnothaveimpressedHobbes.Hewas dismissiveofthetyrannicide’sclaimtothemoraldiscernmentneededfor thejudgementthatsomeparticularruler asitmightbeCaesar was exercisinghisruletyrannically.Hethoughtitalsogavethegreenlightto the ‘dissolutionofanyGovernment’,goodorbad, ‘bythehandofevery murtherousvillain’—andconstitutedarecipefor ‘Anarchy’.Anarchywas indeedtheimmediateconsequenceofCaesar’smurderontheIdesof March,anactthatCicerohadapplaudedandsoughttojustifyasliberation fromtyranny(contemporarypoliticalandgeopoliticalresonancesperhaps ripplethroughthemind).

AtimewhenCicero(orindeedSenecaorPlutarch)couldhavebeen mentionedaspoliticalphilosopherinthesamebreathasPlatoandAristotle seemsremote(andnotmerelymentioned,giventhatitis his stanceon tyrannicidethatisintruthbeingrecalledbyHobbes,ratherthananything onecould findintheirwritings).Allthesame,Cicerohasgraduallybeen edginghiswaybackintopoliticalphilosophy’scurrentframeofreference. Re-examinationoftherepublicantraditioninWesternpoliticalthought, initiatedaboveallbytheworkofQuentinSkinner,hasdonemuchto promptthisdevelopment.Attheheartofthatrevaluationhasbeendemonstrationofthedominantinfluenceof ‘thosewriterswhosegreatestadmirationhadbeenreservedforthedoomed Romanrepublic:Livy,Sallust,and aboveallCicero’.Theseweretheauthorsinvokedin RenaissanceItaly ‘ asa meansofdefendingthetraditionallibertiesofthecity-republics’ 3 Inthe efflorescenceofEnglishrepublicantheorizingofthemid-seventeenthcentury,ancient Rome,asrepresentedintheirwritings,remainsanimportant pointofreference.Itwasintheeighteenth-centuryenlightenmentthat Cicero’ s ‘authorityandprestige’ reacheditspeak.4 AsfortheAmericaof theFoundingFathers: ‘Thenostalgicimageofthe Roman Republic’— mediatedthroughwriterssuchasCicero,Sallust,andTacitus—‘becamea symbolofalltheirdissatisfactionwiththepresentandtheirhopesforthe future’ 5 Thetwenty-three-year-oldJohnAdamswoulddeclaimCicero’ s speechesagainstCatilinealoneinhisroomsatnight.6 Accordingtothe Secret History oftheFrench RevolutionpennedbyDanton’sjournalistallyCamille Desmoulins, ‘the firstactive,activatingrepublicanofthe Revolution’ , 7 itwas readingCiceroatschoolthatinspiredtheFrenchtoloveoflibertyand hatredofdespotism.8

Incontemporarypoliticalphilosophy,aversionofthe Romanidealof politicalfreedom(orasSkinnercallsit,withreferencetotherecoursetothe ancientsintheearlymodernperiod,the ‘ neo-Roman ’)hasbeengiven perhapsunexpectednewlife.Themostnotableandinfluentialtreatment isprobablythatdevelopedbyPhilipPettit,especiallyinhis book Republicanism:ATheoryofFreedomandGovernment.Hiscorethesisisthe claimthatreflectiononthe Romanandneo-Romantraditionenablesusto identifyaconceptoffreedomas ‘non-domination’,which fitsonneither sideofIsaiahBerlin’sdichotomybetweennegativeandpositiveliberty. Adoptionofnon-dominationasthepoliticalidealwould,Pettitargues, giveusa viamedia betweenliberalismandcommunitarianism.Inparticular, itwouldgiveusthepossibilityofamoreradicalandactivenotionofwhat governmentshouldprovideandhowcivilsocietyshouldworkthanthe negativelibertyofprotectionfromcoercionandinterferencethatliberalism makesfundamental,andalesscontentiouswayofapproachingtheideaof thecommongoodthanadoptionofcommunitarianism,insofarasthatis ‘tiedupwithparticular,sectarianconceptionsofhowpeopleshouldlive’ . 9 Pettitinsiststhatnon-dominationisnotjustaparticularapplicationofthe conceptofnegativeliberty.10 Moreimportantthannotbeingcoercedis not beinginastateofdependenceontheuncontrollableandarbitrarywillofanother,even ifthatotherisnotatthemomentactuallyexercisingthatwilltoeffectcoercion Abenevolentdespotmayneverinfactcoerceyouorthreatentodoso, but(asSkinnerputsit)yourdependenceultimatelyonhispowerandwill ‘is initselfasourceandaformofconstraint’,whichwhenyourecognizethat ‘willserveinitselftoconstrainyoufromexercisinganumberofyourcivil rights’ 11 This,inPettit’sformulation,is ‘anolder,republicanwayofthinkingaboutfreedom’,which ‘haditsoriginsinclassical Rome,beingassociated inparticularwiththenameofCicero’ 12

TheCiceropresentedsofarhasbeensomethingofacanonized figure:a ‘ name ’,asPettitputsit,tobeinvokedinlatercenturieswhenauthorityis neededwhetherforsituatingandrecommendingaphilosophicalposition, oralternatively(aswithHobbes)whensuchauthorityisbeingsubverted.In themainbodyofthisbookIamgoingtoundertaketheenterprise very muchinthespiritofSkinner’sownproject oftryingtogetclosertoa historicalCicero,aboveallthroughandinhisownwritings(nowavailable ingoodeditionswithEnglishtranslationsintheCambridgeseries Textsinthe HistoryofPoliticalThought thatSkinnerco-edits),13 readagainstthecontextof

theturbulenterainwhichhelived.Atthesametime,Iproposetoexplore thoseelementsinhispoliticalthoughtthatremainofabidinginterestfor moralandpoliticalphilosophy,especiallybutnotonlyinarepublican register.Intheremainingsectionsofthisintroductorychapter,I firstoffer abrieflifeofCicero(section ).ThenIattemptsomeexplanationofthe currentresurgenceofinterestinhisphilosophicalwritingsingeneral (section ).TherefollowsadiscussionofthequalificationsCicerosuggests areneededforwritingpoliticalphilosophy(section ).Finally,therewillbe ashortaccountoftheagendafortherestofthebook(section ).

.Abrieflife

Romeandthetortuousandintermittentlybrutalandbloodycourseofits politicsinthe finaldecadesofthecollapsing Republicarebythestandardsof mostotherperiodsofancientGreekand Romanhistoryparticularlywell documented,andnevermoreintensivelystudiedanddebatedthanin present-dayscholarship.Cicero, ‘vain,insecureandferociouslyclever’ , 14 washimselfacentralplayer,thoughincreasinglylesscentralthanhewished tobe,intheconstantlyshiftingpoliticallandscape:alandscapethatcanbe chartedfromhisownoftenchangingoropportunisticstandpointthrough thegreatvolumeofsurvivingforensicandpoliticalspeeches,letters,theoreticalwritingsofdifferentkinds,evenpoetry,thathehimselfcomposed.We knowmoreaboutCicero(– BC) sometimesfromdaytodayand weektoweek thanaboutanyoneelseinclassicalantiquity.15

Notsurprisingly,therefore,inmoderntimesithasbeenCicero’slifein politicsratherthanhisthoughtthathasattractedmostoftheattention.His familywerewell-to-doandhighlyeducatedprovinciallandedgentry,from ArpinuminthehillcountryofItalysixtymilessouth-eastof Rome.Itwas comparativelyrareforanyonefromthatkindofbackgroundtobreakinto theintenselycompetitiveworldofpoliticsat Rome,dominatedasitwasbya well-establishedaristocraticelite,andthentomakeitasCicerodidtothe verytop,whenhewaselectedoneofthetwoconsulsfor BC attheearliest possibleageof (deLeg.Agr. –).Itwashispowerasanoratorthathad madehimaforcetobereckonedwith.Soonafterapoliticallycourageous exerciseinsuccessfuladvocacyinhis firstmajorperformanceinthecourts (in BC),hebegantoclimbthepoliticalladder,steadilybuildingand

exploitinghisreputationasanadvocate.In BC,theyearinwhichheheld theimportantofficeofpraetor,heundertookhis firstsignificantventurein politicaloratory,supportingtheappointmentofthepowerfulmilitaryleader PompeytoafurthercommandintheEast(todealwithMithridates,King ofBithynia,aterritoryborderingthesoutherncoastoftheBlackSea). Thenthreeyearslatercametheconsulship,andwithitsupremeexecutive responsibility.

ThiswasCicero’ s finesthour,whichinthefuturehewouldconstantly recallasthecriticalmomentwhenhesavedfromdisasterthe respublica the Romanstateconceivedasacommonwealth,orpoliticalenterpriseinwhich theinterestsofallmajorsectorsofsocietywereatstake.Thethreathe identifiedwasanincipientpopularuprisingledbyadisaffectedmemberof thenobility:theso-calledCatilinarianconspiracy.Catilinehimselfwaskilled inthemilitaryoperationtheconsulslaunchedagainsthim.Butfollowinga voteinthesenatesupportingsuchaction,Cicerohadsomeofhisleading associatessummarilyexecuted.Putting Romancitizenstodeathwithouttrial oropportunityofappeal,howeverexpedientitmighthavebeenjudged, wasanactthatwouldinevitablyprovokecontroversy.Infact,itviolatedthe verylawgivingprotectionagainstsuchactiontowhichCicerohimselfhad appealedindenouncingtheprovincialgovernorVerressevenyearsbefore: Verr. ).16 Hewassoonaccusedoftyrannicalbehaviour,andhis enemieseventuallyhadhimforcedintoexile(in BC).

ThankspartlytoPompey’sgoodoffices,hewasabletoreturnto Rome thefollowingyearandtoresumepublicactivity.ButthewarlordsPompey, Caesar,andCrassusnowexercisedincreasingcontrolofpoliticallife,mostly inconcertwitheachother,andintheearlysummerof BC,aftertheyhad renewedtheirpact,itwasindicatedtoCicerothatheneededfromnowon tobecarefuloverwhatlinehetookinhispoliticalpronouncements.This wasinawaytestimonytotheweighthisvoicestillcarried;andCicerodid notentirelywithdrawfromthepublicscene.Buthiswingshadbeen clipped.Anditwasnow from to (whenhetookupinthesummer thegovernorshipoftheprovinceofCilicia,inmodernsouth-west Turkey) thathe firstturnedinhisadultyearstoserioustheoreticalwriting. Totheseyearsbelong Ontheorator, Onthecommonwealth (discussedin Chapter below,butalsoinsectionsofChapters and ),andprobably Onlaws (apparentlynever finallycompletedorputintocirculation;themain focusofdiscussioninChapter ,but figuringinChapters and also).Itwas

intheselattertwoworks,bothunfortunatelynowfragmentary,where togetherwiththelater Onduties Ciceromadehisprimarycontributionsto politicalphilosophy.

AshewasreturningfromhisyearinCiliciaintheautumnof BC,war betweenCaesarandPompeywaslooming.Theconflictgotseriouslyunder wayinthesummerof ,whenaftermuchvacillation(workedoutoftenin philosophicaltermsinhislettersoftheperiod:seeChapter ),Ciceroended uphimselfjoiningthebulkoftheconservativesenatorialfactionwith Pompey’sarmyinGreece.FollowingPompey’sdefeatinAugust ,he returnedtoItaly,andreceivedapardonfromCaesarinJuly .Inthe followingyear,Caesarwonthelastmajorbattleofthecivilwar,atThapsus innorthAfricaonmodernTunisia’sMediterraneancoast,andtheintransigent StoicMarcusCato,generalofthedefeatedrepublicanforces,committed suicide,therebyachievingundyingfame.Caesarnowruled Rome,inthe exceptionalbuthistoricofficeof ‘dictator’ . 17 Cicerorecognizedthattherewas virtuallynofurtherrolehecouldperforminpubliclife,andturnedonceagain towriting.Between andtheendof hecomposedanimpressivevolume offurthertheoreticalwriting,initiallyonoratory,butthenasequencemostly ofphilosophicalworks.Mostofthesewerewritteninthedialogueform pioneeredbyPlatoandotherassociatesofSocrates.Ineffect,theywould constitutesomethingwithinstrikingdistanceofanencyclopediaofthewhole ofphilosophyfortheedificationof Romanreaders.

March howeversawtheassassinationofCaesarbyBrutus,Cassius,and theirassociates(Cicerohadnothimselfbeenenlistedintheconspiracy,and infactseemstohavebeenmidwaythroughcompositionofhis Ondivination atthetime: Div. –).InthelatesummerofthatyearCiceroresumed publicactivityinearnest,andearlyinSeptembermadethe firstofhisattacks onMarkAntony,Caesar’spoliticalheir,inthefamoussequenceofspeeches knownasthe Philippics,whichweretocontinueuntilApril .Buthe continuedhisphilosophicalwriting,andinthelattermonthsof completed Onduties (deOfficiis),hisguidetothevirtuestobeexpectedofthe maninpubliclife(seeChapters and ).18 Withthefollowingyear() camerenewedmilitaryhostilities,andinNovemberarapprochement betweenthenewascendantwarlords:Antony,MarcusAemiliusLepidus, andCaesar’sadoptedsonOctavian,eventuallytobecometheemperor Augustus.Alistofopponentstobeeliminatedwasdrawnup,andon DecemberthehitmencalledonCicero.

Cicerothereforemetamiserableend,consciousnotonlyofthefrustrations andfailuresofhisownlifeinpolitics,eversincethetriumphantyearof ,but evenworseofthedemiseofeverythinghehadchampioned,includingthe verypossibilityofaparticipatoryrepublicanpoliticsandoftheoratoryof whichhehadbeenthemaster.Intheprefacestothephilosophicaldialogues of ,inparticular,hemakesitplainthattheircompositionistheoccupation ofanenforcedleisurehewouldprefernottohavetobe filling.Hesawhis trueroleasinvolvementinthepublicsphere,promotingthegoodofthe res publica bypoliticalactivity.Thechoicebetweenthephilosophicalandthe politicallifeisinfact flaggedasakeyissueinboth Onthecommonwealth and On duties,withthedecisiongoingunequivocallyinfavourofpoliticalengagement.NonethelessCiceroalsorepresentshisphilosophicalwritingsasservice tothe respublica inanothermode.Theywillequip Romanswiththebasisofa philosophicaleducation,focusedaboveallonethics:howtolive.Theywill dosobyspeakingto RomansintheirownLatinlanguage,which ashe intendstodemonstrate possessesresourcesforthepurposequitetheequalof thoseavailabletoGreek,ifnotindeedricher.

.Rehabilitation

‘Throughthesehastycompositions’,wroteD R ShackletonBailey,distinguishededitorandaficionadoofCicero’sletters, ‘Greekthought,especially ofthetwoandahalfcenturiesafterAristotle, filtereddowntomouldthe mindsofChristianFathersandeighteenth-centuryphilosophers astupendoustriumphofpopularization,whichhashaditsday.’19 Thatstatement in abiographyofCiceropublishedin wasaparticularlyeloquent expressionofaviewofhisphilosophicalwritingsthathashadwidecurrency. EversincePlatoandAristotleinthenineteenthcenturyregainedeffective recognitionintheconsciousnessofeducatedpeopleasthephilosophical giantsofclassicalantiquity,hisphilosophicalstockhasundeniablylostvalue. Hehasoftenbeenperceivedasmerelyderivative,notevenattempting anythingmorethanfaithfulreproductionofhissources,andforallhis unquestionable fluencysecond-rate.

Butperceptionsinrecentdecadeshavebeenchanging.Threereasonsfor thisdevelopmentareworthhighlighting:reflectingrespectivelyphilosophical,literary,andhistoricalassessmentsofthephilosophicalworks.Onekey

factorhasbeenarevivalofphilosophicalinterestinHellenisticphilosophy. Thepowerandsubtletyofthetheoriesandargumentsadvancedinthethree centuriesafterAristotle(whodiedin BC)byStoicsandEpicureansand thescepticsoftheHellenisticAcademy,thedebatesinwhichtheyengaged witheachother,thewaytheyconceivedoftheirentirephilosophicalprojects, andtheirimpactontheWesternphilosophicaltradition,areallnowbetter understoodandrathermoreappreciated.20 SoifmostofCicero’sphilosophical writingpresentshisreaderswiththephilosophizingoftheHellenisticschools, thisfocushasmadehimmore,notless,attractive.Theclarityandprecisionof histreatmentsofthismaterialmaysometimesdisappoint.Byandlarge, however,timespentwiththemyieldssignificantrewards.Fewscholarswho workseriouslyonCicerotodayareunawareofthistransformationofthe standingofhisphilosophicalwritingsintheeyesofthosewhoengagewith ‘Cicerothephilosopher’,tousethetitleofarespectedandinfluential collectionofessayspublishedtwenty-fiveyearsagonow.21

HehimselfwasneitherEpicureannor asissometimessupposed Stoic, although(ashetellsusinanautobiographicalsectionofhisdialogue Brutus) fromhisearlytwentiesheworkedwiththeGreekStoicDiodotus,whowas toliveinhishouseforthebestpartoffortyyears(Brut. ).Hisinitialstudy ofphilosophywaspursuedwithPhiloofLarissa,theheadofPlato’sAcademyinAthens,whohadhowever fledto Romein BC.Hesubsequently resumedseriousphilosophicalstudyforaperiodofsixmonthswithanother Academic,AntiochusofAscalon,duringalongvisittoAthensandAsia Minorin – BC (Brut. , ).CiceroveneratedPlato,andfelthimself mostathomewiththePlatonicdialogue,bothasaliteraryvehiclefor philosophyandforitsarticulation,perpetuatedintheAcademy,ofphilosophyasdebate,notattemptingtheconclusivedemonstrationsthatthetreatise writingoftheotherschoolsoftenaimedtosupply.ThespiritofPlato permeateshisown firstmajorwritingsonrhetoricandphilosophyof – BC 22 Inthewritingsof – BC heisexplicitinidentifyinghis ownpositionasthatoftheAcademicsceptic,whichrequiresthatone argumentshouldbepittedagainstanother andifoneofthetwoseems intheendclosertothetruththantheother,thatisthemosthumansare legitimatelyentitledtoconclude,andinanycaseamatterforthejudgement ofthereader.IhavearguedelsewherethatCicero’sdialoguesofthisperiodare genuinelymorebalancedandopen-ended andintheserespectsmore dialogic thanPlato’s,withwhomheissometimesunfavourablycompared.23

Thehigherstandingofhisphilosophicalwritingsisnotsimplyafunction ofenhancedappreciationofHellenisticphilosophy.Literaryscholarswho approachtextsasculturalartefactshavebecomefascinatedwiththeway Ciceroprojectshisownvoiceandstanceinhisphilosophicalwritings,and withwhathebringstothematerialhepresents,asacultivatedmemberof the Romanelite,alerttothedelicacyofthenegotiationbetweenGreek languageandcultureand Roman,andfrequentlyinsistentthatthelongestablishedvaluesandinstitutionsofthe Republicareindisrepairand perhapsunderthreatofoblivionashewrites.24

The RomanizationofGreekphilosophywasaprojectwhosedifficulties andopportunitiesCicerofrequentlydiscussedintheprefaceshewrotetohis dialogues,attimesratherdefensively,butoften conbrio: ‘Ithoughtitmattered alotforthegloryandhonourofthecitizenbody(civitas)’,hesaysinthe prefaceto Onthenatureofthegods, ‘togiveideasofsuchimportanceandso greatlyrespectedaplaceinLatinliterature’ (ND .).25 Amongotherdevices heemployedforthepurposewashischoiceofspeakersforhisdialoguesand ofthelocationsinwhichhesetthem:nottheteenagersorSophistsPlato’ s SocratesencountersingymnasiaorinthetownhousesofmoneyedAthenians,butdistinguished Romanpoliticians,representedaswellversedinphilosophy,occupyingtheirleisureinthegardensofgrandcountryvillas.The implicationisthatphilosophyisinfactalreadywellensconcedin Romanelite culture,andnotintheleastincompatiblewiththeserioustraditionalpublic businessofstatesmanship.26 Butinhisdialoguesettingsandspeakerselection Ciceroalsohadanotheranddarkeragenda.

Mostofthespeakersinthephilosophicaldialoguesof – BC,notjust Cato(advocateofStoicisminBooks and of Onends),wouldlosetheir lives fightingintherepublicancausesoonafterthe fictiveoccasionson whichCicerohadthemconversingonphilosophicalthemes.Throughsuch apointedchoiceofcastheneverletsreadersforgetwhatheseesasthe disastrouslossofthatcause.Butforthemostpartthemessageremainsa subtext.Themostobviousexceptionisthe firsttheoreticalcompositionof thelatersequence,the Brutus of BC,ahistoryof Romanoratorywhose prefaceandconcludingpages(Brut. –, –)openlybewailthe ‘night’ whichhasengulfedthe Republic.Nearlytenyearsearlier,in Ontheorator,the untimelydemisein BC ofCrassus,theleadingspeaker,27 hadevokedin Cicero’swritingwhatIngoGildenhardhascharacterizedasasimilar ‘moodof pessimismandgloom’ and ‘senseofimpendingcatastrophe’ (deOr. –).28

Nolessimportantforthere-evaluationofCicero’scontributiontothe literatureofphilosophyhasbeenchangeanddiversificationinthewritingof Romanhistory,asofhistorymoregenerally.If fiftyyearsagoyouhadasked a Romanhistorianhowthe Roman Republicwasgoverned, ‘oligarchy’ wouldhavebeentheshortanswer,andindeed howeverelaborated the coreofalonganswertoo.InthemindsofEnglish-speakingreadersthat viewhadbeengivenbrilliantandinfluentialcrystallizationin RonaldSyme’ s

The Roman Revolution of . 29 PeterBrunt,writingin ,begana chapterofhisbookonthefallofthe Roman Republicwithasketchof Syme’sviewofthepoliticaldiscourseofthelate Republic:30

Inthepoliticalstrugglesofthelate Republicfrequentappealsweremadeonallsides to libertas. ForSymetheywereessentiallyfraudulent. ‘Libertyandthelawsarehighsoundingwords.Theywilloftenberendered,onacoolestimate,asprivilegeand vestedinterests.’ Thenameoflibertywasusuallyinvokedindefenceoftheexisting orderbytheminorityofrichandpowerfuloligarchs. ‘Theruinousprivilegeof freedom’ wasextinguishedinthePrincipateforthehighergoodof ‘securityoflife andproperty’

Bruntexpressedtheview whichhassinceinoneformoranotherbecome somethingapproachinganeworthodoxy thatthisanalysiswasimprobably reductionist:31

ThoughSymewasrightinholdingthatonthelipsofthenobilityitoftenveiledtheir selfishattachmenttopoweranditsperquisites,hewaswronginmyjudgementin suggestingatleastbyinsinuationthatitwasnomorethanacatchword,proclaimedin consciouscynicism,andthatsome,perhapsmost,ofthemdidnotsincerelybelieve thatthelibertyorpowertheypossessedunderthe Republicanconstitutionwas essentialtothepublicgood.Inthesamewaythecommonpeopleweresurely attachedtothedifferentpersonalandpoliticalrightswhichtheirspokesmensubsumedunderthenameoflibertybysentimentandtradition,aswellasbyconsciousnessoftheconcreteadvantageswhichtheserightssecuredtothem.

Ortoputtheargumentsomewhatdifferently,Symehadcruciallylefttwo thingsoutofthepicture.Onewasindeedthepeople,whetherthatincreasinglysmallpercentageof Romancitizenswhichwasconstitutedbythenonelitemalepopulationofthecityitself,orthewholebodyofcitizens,now includingtheincreasinglylargenumbersofrecentlyenfranchisedItalians andofarmyveteranssettledintheItalianhinterland.32 Justhowmuchpower the Romanpopulaceexercisedatassemblieswheretheywouldvotealong

withthepropertiedclasses(whosevotesweremoreheavilyweighted)on legislationandinelectingmagistrates,orinthemassmeetingswhere politicianswouldattempttogainsupportonissuesthatassemblieswereto decide,orastheaudiencethrongingtrialsbeforemagistratesorstanding courts,hasbeenintenselydebatedformorethanaquarterofcentury.33 Rent-a-crowdhaditsancientequivalents.Nonethelessthereisnodenying that Romanaristocratshadtoexpendagreatdealoftimeandenergyin persuadingpopulargatherings.Anditisclearthatintheconstantlyshifting politicallandscapeofthelate Republicitbecameincreasinglydifficultforthe senatetoremaincohesiveandtoguaranteeconsistentcontrolofthem.34 Morespecifically,despitesignificantsenatorialresistance,thepopularassemblieswereablebetween and BC tovoteintobeinglawsconstraining thesenate’sdiscretionarypower(forexample,toassigncommandofmajor wars),defendingpopularrightsandpowers,andestablishingmaterialbenefitsforthe plebs,theordinarycitizensof Rome.35

Theother,andcloselyconnected,drawbacktoSyme’sassessmentwashis treatmentofideology.Ideologymightbetterbeseennotasprimarilycynical windowdressing,butas ‘itselfaninstrumentofpower,perhapsthemost effective(andcertainlythecheapest)onethereis’ . 36 NicolaMackie author ofthosewords continued:

Theeffectivenessofideology whatdistinguishesitfrom ‘propaganda’—liesinits capacitytoappearasmorethananinstrumentofnakedclass-orself-interest;its capacity,thatis,tobaseitselfon ‘objective’ moralstandards,andso firethe enthusiasmofthoseinwhoseinterestitis,andalsoconvince(oratanyrate disconcert)thoseinwhoseinterestitisnot.Onlythisconceptionofideologycan explaintheroleplayedbyitin Romanpoliticsinthelate Republic.

Aswiththeroleofthepeople,therehasbeenplentyofdebateoverquite howideologyinformedpoliticalstances,andwhethertherewereany fundamentalideologicaldifferencesbetweenpoliticianswhoclashedon importantmattersofpolicy.37 Butonceideologyisrecognizedasakey factorintheshapingofpoliticalagency,andsoasindispensableforhistorical explanation, Romanpoliticalphilosophyhasanimmediateclaimonthe historian’sattention.

‘Modernaccountsofthe Roman Republic’,wrotethehistoriansMary BeardandMichaelCrawfordbackin , 38 ‘tendtoplaceitsculturaland religioushistoryatthemargins’.However: