Acknowledgments

In the course of researching and writing this book I have incurred many debts beyond my ability ever to repay. From an academic perspective, the earliest of these debts goes back to the time when I was an undergraduate in East Asian Studies at Harvard College. My senior thesis advisor, Philip Kuhn, gave up much of his valuable time to advise and mentor me. As I sat in his office on one occasion, books crowding around in all three dimensions, Professor Kuhn said, “You and I are similar. We’re both interested in truth.” Up until that point I had thought that history was about sources, voices, and narratives, but that “truth” was somehow beyond the reach of scholarly research. As I continued to learn from Professor Kuhn in graduate school, however, I came to understand a bit more about what he meant, from his meticulous readings of primary sources and his engagement with the authors of the texts as if they were living, breathing human beings—which, of course, they were.

This book began as my doctoral dissertation, supervised by Henrietta Harrison. Professor Harrison not only taught me in two graduate courses but also mentored me throughout several years out of residence as I juggled the care of four young children (two born before the dissertation was completed and two within the following two years). Her advising-by-email must have been so inconvenient and tedious. I so appreciate her unfailing encouragement and thoughtful insights—not just about research, but about being an academic and a human being. Throughout the years I have been honored to have such a brilliant, generous, and lively teacher. Michael Szonyi introduced me to the history of Chinese popular religion and offered rigorous feedback on dissertation drafts. David D. Hall, who taught me about American religious history as an undergraduate, also gave wonderful advice as a member of my dissertation committee. During graduate study, I learned a great deal from Nancy Cott, who took the time to read and comment extensively on early essays in which I was still learning to speak Scholarese and who directed my general examination field in American history.

Acknowledgments

A year of dissertation research during which I acquired the bulk of the material for this book was supported by the Harvard Graduate Society Dissertation Completion Fellowship, the Harvard- China Fellowship, and the Foreign Language and Area Studies grants of the US Department of Education. I also received generous support for research in other sites by the Religious Research Association Constant R. Jacquet Award and the Association for Asian Studies China and Inner Asia Council Small Grant Award. Writing and further research was supported by the University of Auckland and in particular the very generous University of Auckland Faculty Research Development Fund New Staff Grant. I received kind administrative and logistical assistance from the Shanghai Municipal Library and the New Zealand Centre at Peking University.

During my research in China I was hosted generously by Chinese academic institutions, including Fudan University, which administered the Harvard- China Fellowship. Li Tiangang at Fudan was a warm and helpful mentor. At the headquarters of the True Jesus Church in Taiwan, I was received very kindly by the staff, with special assistance from Hou Shufang, the headquarters librarian. Kar C. Tsai, a leader of the True Jesus Church, was extremely kind in helping me make needed connections within the church. I received tremendously helpful advice from Chinese scholars of religion such as Zhang Xianqing. Jan Kiely was gracious and generous in helping me to make contacts with local scholars and archives. Paul Katz gave candid and thoughtful advice about professional correspondence and grant applications. During my years working in the archives at Hong Kong Baptist University, sometimes with a kid in tow, Irene Wong and her colleagues combined competence with humor and collegiality.

In the midst of my fieldwork, I benefited from a productive exchange of ideas about the True Jesus Church and Chinese Christianity with David Reed, Chen Bin, Chen-Yang Kao, Gordon Melton, Jiexia Elisa Zhai, Daniel Bays, Tsai Yen-zen, and Chris White. Joseph Tse-Hei Lee’s generous and savvy advice on how to access Chinese archives and his broad insights into the significance of Chinese Christian institutions have shaped my development as a scholar. Li Ji gave a thoughtful and helpful review of the dissertation manuscript and was a wonderful colleague during my time in Hong Kong. Benjamin Liao Inouye read sections of the dissertation manuscript and pointed out places where it was unreadable, with comments such as “Is this really what academic writing is supposed to be like? This sentence is about five times too long.”

In the process of revising the manuscript for publication, I received support and encouragement from my colleagues in Asian Studies and History at the University of Auckland, including Mark Mullins, Ellen Nakamura, Paul Clark, Stephen Noakes, Richard Phillips, Jennifer Frost, Karen Huang, and Nora Yao. Mark, Ellen, Paul, Stephen, and Richard all read and commented helpfully

on large chunks of the manuscript, pointing out errors and posing productive questions. Student research assistants Kayla Grant, Jessica Palairet, Charles Timo Toebes, and Zhijun Yang helped with research and commented on drafts. Departmental heads Robert Sanders and Rumi Sakamoto supported my research. In addition, Henrietta Harrison, Michael Ing, Yang Fenggang, Haiying Hou, Amy O’Keefe, Steven Pieragastini, Paul Mariani, Thomas Dubois, Laurie Maffly-Kipp, Stuart Vogel, Charity Shumway, Mei Li Inouye, and Charles Shirō Inouye read and commented on sections of the manuscript. Jason Steorts read and commented on the entire manuscript. I am so grateful that these brilliant and busy people made the sacrifice of time and energy to mull over my homely paragraphs and clunky sentences. I also received helpful feedback at a March 2017 Association for Asian Studies panel organized by Ryan Dunch, with comments by Xi Lian.

Material from two of the chapters in this book has been published previously. A narrative of transnational relationship between Wei Enbo and Bernt Berntsen in Chapter 2 appeared in Global Chinese Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2017), edited by Yang Fenggang, Allan Anderson, and Joy K. C. Tong. The discussion on the True Jesus Church’s accommodation with the Maoist state in Chapter 6 appeared in the journal Modern China (March 2018). I thank these two publishers for allowing me to include these materials in this book.

Two anonymous peer reviewers for Oxford University Press provided astute feedback on the manuscript as a whole, and the editorial and production team, including Cynthia Read, Drew Anderla, Rajakumari Ganessin, Sangeetha Vishwanathan, Victoria Danahy, and others made invaluable corrections and suggestions. I am indebted to all of these thoughtful and critical readers for their time and insight. I would like to emphasize that any remaining errors in this manuscript are mine alone.

I am thankful to people who have mentored me more generally throughout the years: Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, a brilliant and caring advisor who graciously declined when in our first email interaction I mistook her for a Harvard undergraduate and invited her to a sleepover, Claudia Bushman, my first postgraduate teacher and a perennial source of inspiration, and Terryl and Fiona Givens, who have supported and encouraged me through numerous projects, including this one. As I look back on my life as a student, I am thankful for the time and talents of people who taught me even when I was not very teachable, including Dillon K. Inouye, Paul Fitzgerald, Linda Williams, Charlie Appell, and Eileen Chow. I learned so much from fellow graduate students at Harvard including Jie Li, Allison Miller Wang, and Michael Ing. I am especially grateful to Tanya Samu, Sharyn Wada Inouye, Amy Hoyt, and Sherrie Morreall Gavin, who went out of

Acknowledgments

their way (a really long way) to support me as I worked to complete this manuscript in the midst of a significant health challenge.

Finally, I am indebted to my family. My deepest debt is to my parents, Susan Lew Inouye and Warren Sanji Inouye, who loved learning, supported my study, and taught me to value the beauty of the world, including the beauty of my fellow beings. This book is dedicated to them. My mother passed away several years ago, but I like to think that somewhere—though who knows where—she is aware of my deep, abiding gratitude and respect. I am thankful to my father and Catherine A. Tibbitts for being such awesome grandparents to my children and caring advisors to me. I am grateful for my grandparents, Marjorie Ju Lew and Hall Ti Lew, Charles Ichirō Inouye and Bessie Murakami Inouye, who have always loved me unconditionally and who admonished me to be humble and work hard. I am grateful for Gor Shee Ju, Gin Gor Ju, Mikano Inouye, Sashichi Inouye, Kume Uchida Murakami, Denji Murakami, and all those ancestors whose trials, triumphs, and growth created the basis for my life. I am thankful to my aunt and uncle, Elizabeth Ann Inouye Takasaki and Roman Y. Takasaki, for giving me and my family another home away from home, and to my cousins Stephen, Aimee, and David, for sharing their home with my siblings and me. I am grateful to my brothers, Abe, Ben, Isaac, and Peter, and to all of my aunties, uncles, and cousins who have supported my family and me with especial fierceness in my mother’s absence. I am thankful to my parents-in-law, Joy Anne Cahoon McMullin and Phillip Wayne McMullin, for their unfailing support for me and kindness to my children. I am thankful to my four children (nicknamed Bean, Sprout, Leaf, and Burger 豆 芽 菜 汉 堡 ) for their cheerful spirits, bright minds, kind actions, and helping hands. Last of all, I am grateful to my husband, Joseph Phillip McMullin, for being so very amazing all these years, and for being such an incredible partner in the projects of international itineration, home renovation, and getting the Bean, Sprout, Leaf, and Burger potty-trained, literate, and civilized.

Chronology

[Bold font identifies significant characters in this book’s narrative]

1583 Matteo Ricci founds first permanent Christian mission in Zhaoqing

1644 Qing dynasty invades China; Ming court flees southward

1807 Robert Morrison, first Protestant missionary, arrives in Guangzhou

1838 Zeng Guofan passes the highest level of the civil service examination

1839–1842 First Opium War between Great Britain and China; Treaty of Nanjing

1850–1864 Hong Xiuquan leads the Taiping Rebellion

1872 Samuel Meech and Edith Prankard marry in Beijing

1879 Birth of Wei Enbo

1885 Birth of Yang Zhendao

1894–1895 First Sino-Japanese War

1897 Lillie Saville runs a dispensary in Beijing

1898 Hundred Days’ Reform; Empress Dowager Cixi places Emperor Guangxu under house arrest

1899–1900 Boxer Uprising; Lillie Saville receives Royal Red Cross for work during siege

1904 Samuel Meech baptizes Wei Enbo and Wei’s mother in Beijing

1905 Civil service examination abolished; Wei Enbo opens permanent shop; Edith Murray reports on Cangzhou London Missionary Society revival

1907 Bernt Berntsen receives Holy Spirit at Azusa Street revival

1911 Chinese Revolution; end of the Qing dynasty

1912 Republic of China established

1914 World War I begins in Europe; China supports the Allies with laborers

1915 Wei Enbo meets Bernt Berntsen and speaks in tongues for the first time

1917 Wei Enbo’s baptism and vision; True Jesus Church established

1919 World War I ends; May Fourth Movement; Wei Enbo’s death; Wei’s wife Liu Ai “is a bishopess” of the True Jesus Church

1921 Mao Zedong attends Founding Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in Shanghai

Chronology

1922 National Christian Conference in Shanghai (Gao Daling, Zhang Barnabas, and Wei Isaac in attendance); Wei Enbo’s end-of-the-world deadline

1925 May Thirtieth Incident

1926 Zhang Barnabas provokes split between northern and southern churches, organizes General Headquarters

1927 Northern Expedition of Communists and Nationalists; United Front falls apart

1930 True Jesus Church General Assembly excommunicates Zhang Barnabas

1931 Japan invades northern China and creates puppet regime

1932 Japanese attack on Shanghai destroys True Jesus Church General Headquarters; northern and southern True Jesus Churches reunify

1934–1936 Communist troops complete Long March to new base in northwest China

1935 Death of Yang Zhendao

1937–1945 Second Sino-Japanese War; True Jesus Church Headquarters moves to Chongqing

1947 Thirtieth anniversary of the founding of the True Jesus Church; Wei Isaac heads the church

1949 Communists establish new government; Nationalists decamp to Taiwan

1950–1953 Korean War heightens antiforeign sentiment; foreign missionaries expelled

1951 Three-Self Patriotic Movement organized; Christian Denunciation Movement launched

1952 Wei Isaac’s “confession” appears in Tianfeng (organ of Three-Self Patriotic Movement); Jiang John and Li Zhengcheng lead True Jesus Church

1956 Jiang John speaks at Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in Wuhan

1957 Anti-Rightist Campaign targets intellectuals; Li Zhengcheng arrested and sentenced to labor camp

1958 Jiang John and other True Jesus Church leaders arrested

1958–1961 Great Leap Forward

1964 The Red Detachment of Women comes to the stage

1966–1976 Cultural Revolution

Mid-to-late 1960s, early 1970s

Deaconess Fu grows up singing from a handwritten hymnbook and praying with her mother and grandmother, behind drawn curtains

1974 Wang Dequan’s vision sparks revival of True Jesus Church activity in China

1976 Death of Mao Zedong; fall of the Gang of Four ends Cultural Revolution

1980 Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening up” policies create Special Economic Zones to encourage foreign investment

1982 Document 19 expresses official toleration for “normal religious activity” including Christianity

Mid-1980s Deaconess Fu (pseudonym) and her True Jesus Church colleagues minister to the woman who committed suicide

1989 Tiananmen Square student demonstrations; True Jesus Church International Assembly is officially registered in California, United States

1995 Mother of seven-year-old Zhang Pin (pseudonym) prays for his miraculous resuscitation after he falls into a shrimp pond

2001 China joins the World Trade Organization

2007 Ninetieth anniversary of True Jesus Church’s founding; churches established in a record four new countries including Lesotho, Zambia, United Arab Emirates, and Rwanda

2008 Mr. Chen (pseudonym) and other True Jesus Church preachers in Beijing touring the 2008 Olympics venue exorcise their colleague

2012 Xi Jinping elected General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party

2017 12th World Delegates Conference, 1st Session, held in Taiwan, on 100th anniversary of True Jesus Church founding; number of churches established outside China reaches fifty-seven

2018 National People’s Congress votes to remove term limits for Xi Jinping and enshrine “Xi Jinping Thought” alongside “Mao Zedong Thought” in the Constitution

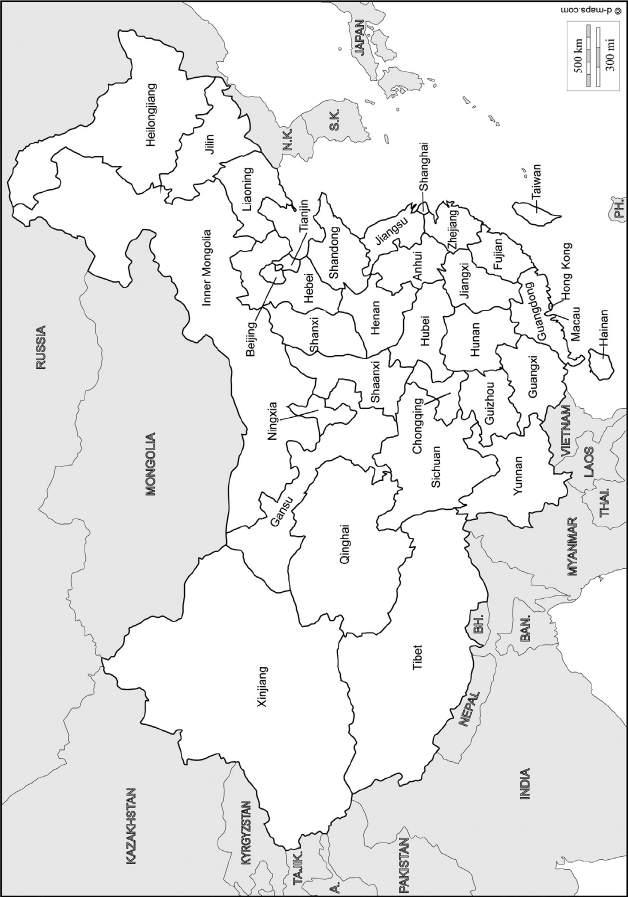

Map 1. Contemporary map of China’s provinces, municipalities, and special administrative regions.

Credit : Base map from d-maps, http://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=11572&lang=en

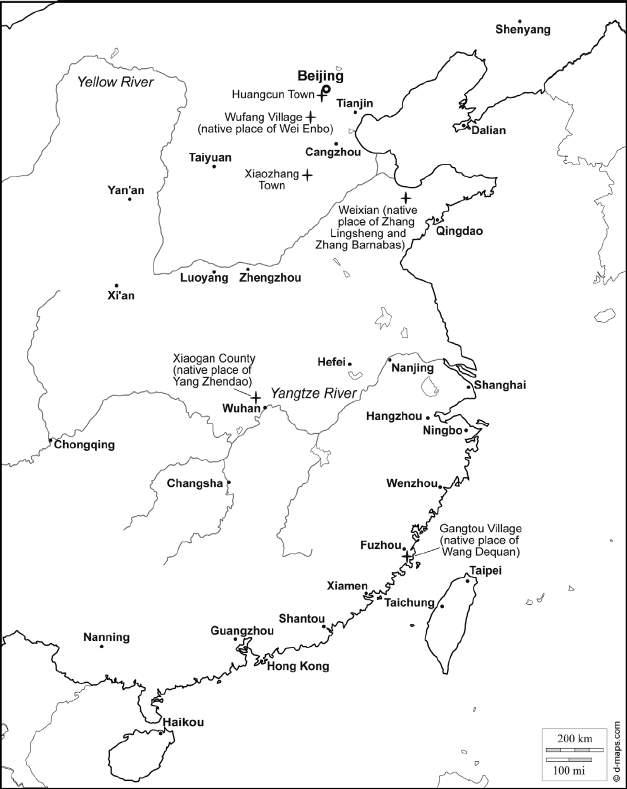

Map 2. Important cities, rivers, and places mentioned in this book.

Credit: Base map from d-maps, http://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=17512&lang=en

China and the True Jesus

Introduction

Extra-Ordinary

Deaconess Fu told me about the woman she helped raise from the dead.1 The two of us sat on a faux-leather couch in the small living room of a ground-floor apartment in a city in South China. The area just outside was undergoing construction. One by one, the old apartment blocks would be razed, and modern high-rises would be built in their place. It was late in the afternoon, and the backhoes were still and silent. The happy shouts of children rang out as they climbed, chased, and leaped among a stack of massive concrete pipes piled on the bare red earth.

This incident, Deaconess Fu said, had taken place in the mid-1980s, early years of the “reform and opening up” period after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. These early years saw the beginning of the revival in China of both capitalism (i.e., “socialism with Chinese characteristics”) and organized religion aboveground. Deaconess Fu described the woman: a member of the True Jesus Church, in her mid-thirties, with four young children and a troubled marriage. One day after an argument, her husband left the house in a temper. Shortly thereafter a stranger, whom Deaconess Fu believed was the Devil in disguise, arrived at the house.2

“Your life is so terrible,” the stranger told her. “You would be better off dead.” The stranger pointed to the cords for raising and lowering the window shades. When the stranger left, the woman hanged herself from the cords. Her husband returned and found her, apparently lifeless. Three doctors examined her and pronounced her dead. Three women from the True Jesus Church came to the house, including Deaconess Fu, who was at the time a young seminary student, and an elderly sister “who was full of faith.” Because the woman was in her prime and had four young children, they decided to pray for a miracle—although Deaconess Fu was afraid. “The face was all dark,” she recalled, “and the tongue was very long. It was very ghastly.” The elderly sister cried, “Don’t be afraid. Just pray!” She went to

the woman’s body and placed hands on her head. The second church sister took hold of the woman’s hands. Deaconess Fu gingerly took hold of the woman’s feet, which were cold. They began a cycle of hymns of exorcism—because the elderly sister suspected the Devil’s work—followed by thirty minutes of prayer.

After two hours, the woman’s feet suddenly moved. Deaconess Fu shrieked and let go. The elderly sister urged them to redouble their efforts. They prayed harder. Soon the woman’s whole body began to move, and she revived. One of the doctors was a relative of the family and so was still present at the house. Impressed, the doctor mused: “Her ancestors must have done something very meritorious.” “It wasn’t her ancestors who did this,” Deaconess Fu snapped, wanting proper attribution. “It was Jesus!”3

In 2010, when Deaconess Fu told me this story, she wanted me to understand that this story was not about her or about underdeveloped conditions in China in the early 1980s (healthcare lacking, economy sluggish, social fabric torn by the Cultural Revolution), or even about a mother who suffered from depression. It was about a struggle between the Devil and Jesus, about the divine hand suspending natural laws in response to a collective petition made in faith.

Around the same time, I interviewed another True Jesus Church leader named Deacon An. He was a kindly older man, his manner formal but hospitable as he poured just-boiled water into a thin plastic cup that sagged with the heat and set it before me on the wooden table. Like Deaconess Fu, he took the same tack in pointing to divine influence in human events, but he was even more explicit in how he thought I should interpret his account. “If you are not clear about a few things, you cannot possibly understand our church,” he told me. “You must acknowledge the hand of God in creating the True Jesus Church. It is part of God’s saving work, part of God’s plan of salvation . . . . The True Jesus Church was established in China in 1917. This was part of God’s plan from the beginning. Even [the ancient Chinese philosopher] Laozi 老子 and the Dao De Jing 道德经 [a book attributed to Laozi] were intended by God to lay a foundation for the True Jesus Church.” He paused and looked at me searchingly across the wooden table between us. “Without this understanding, you cannot possibly write the history of the True Jesus Church.”4

The True Jesus Church was founded in 1917 in Beijing by a rags-to-riches silk merchant named Wei Enbo 魏恩波 (surname Wei, personal name Enbo). Wei—who later took the Christian name Baoluo 保羅 [Paul]—claimed to have seen a vision in which Jesus appeared to him, personally baptized him, and commanded him to “correct the Church,” restoring Christianity to its original purity. Although Wei died in 1919, just two years after establishing his movement, the True Jesus Church continued to flourish under the leadership of Wei’s

associates and his son, Wei Yisa 魏以撒 [Isaac]. By 1947 the True Jesus Church had become one of the largest independent Protestant denominations in China.5 Today it is one of the most distinctive strains of Protestant Christianity within the state-sanctioned churches of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and also has congregations in places such as Taiwan, the United States, and South Africa.

The claims of both Deaconess Fu and Deacon An are charismatic in nature. In everyday conversation, the word charismatic most usually describes an individual’s magnetic or forceful appeal, such as in the case of Jesus, Joan of Arc, and Adolf Hitler. Sociologist Max Weber pointed out the significance of this kind of personal charisma. It is a source of authority that generates political legitimacy. According to Weber, this kind of authority rests on “devotion to the exceptional sanctity, heroism, or exemplary character of an individual person, and of the normative patterns or order revealed or ordained by him.”6 This sort of authority extends beyond secular political loyalties and into the sacred polities created within religious and moral–philosophical movements. Joseph Smith, Jr., founder of the Mormon tradition, for instance, was described by many of his followers as a magnetic personality who stood out in a crowd. Kong Qiu (Latinized as “Confucius”), the ancient philosopher, inspired such personal loyalty that his disciples wrote down his words and living example in the Analects 論語, which became one of the foundational texts for Chinese moral and political discourse for thousands of years.

In contrast to this personality-based definition, in an academic religious studies context the word charismatic describes something manifesting power that is extraordinary or divine. “Charismatic” is the adjectival form of the noun “charisma,” from the Greek χάρις/charis [grace]. In the study of Christianity, “charismatic Christianity” is a type of Christianity emphasizing the gifts of the Holy Spirit, such as speaking in tongues, prophesying, and healing. A particular strain of charismatic Christianity in the twentieth century followed on the heels of the early twentieth-century Pentecostal movement and is commonly known as the charismatic movement.7 Charisma is also an important concept for scholarship on religions other than Christianity. For example, Stephen Feuchtwang and Wang Mingming recently offered a broad definition of charismatic religious movements.8 In their interpretation, charisma goes beyond the personality of an individual leader and includes “a message which . . . resonates with and gives authority to followers’ expectations and assumptions.”9 Historically, after leaders with charismatic personalities have died, their movement has survived or expired, partly depending on whether the message or worldview they have inspired is sufficiently charismatic. Altogether, charismatic beliefs and practices create an ethos, a shared “expectation of the extraordinary,” that provides a community’s authoritative center.10 To put it simply, in a world full of compelling distractions, in order

to attract and retain a large group of people to a new cause, what one has to offer must be perceived as truly remarkable.

Depending on one’s perspective, there are different explanations for why Wei Enbo’s vision was so attractive to others of his time and place. The True Jesus Church provides interesting subject material for religious studies, Chinese social history, Chinese popular religious history, and global Pentecostal and charismatic history. Also critical is the perspective of members of the True Jesus Church themselves. These various points of view are grounded in different assumptions, values, texts, and experiences that often overlap but also diverge widely. For example, the question of “Did Wei actually hear God’s voice, or was he just making it up?” is very important to a True Jesus Church practitioner, but not necessarily on the table in terms of the major arguments a religious studies scholar would make. Numerous historians have pointed to the significance of Chinese nationalism in the rise of the True Jesus Church, but church members would of course say their church’s rise was due to the divine revelation of its founding events and the correctness of its claims about truth.

This study is an attempt to illuminate the substance of charismatic ideology and experience within the True Jesus Church. The more interesting and fruitful question to ask about someone’s charismatic experience is not “Did it really happen?” but “What did people do with it?” To acknowledge the significance of the divine elements in the history of the True Jesus Church, and also to simplify the prose, in my account I will not constantly flag religious claims with language such as “Wei claimed to have heard a voice” or “Wei alleged he battled with evil spirits.” As I have done in the opening of this introduction, the prose recounting claims made in primary source texts will adhere to those texts as closely as possible. In the accompanying discussion, I will apply additional analytical perspectives. My overall project is to understand how charismatic claims inspire human organization and hold communities together.

Existing Scholarship on Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity

Existing scholarly analyses of the True Jesus Church and independent Chinese Christian movements more generally have chronicled the truly dismal parade of social crises that shaped many converts’ daily reality: foreign imperialism, floods, droughts, famines, warlordism, and banditry. Many studies have acknowledged the circumstances of socioeconomic, political, or psychological deprivation in which many early converts lived and suggested that the True Jesus Church’s charismatic healing practices and ecstatic worship were attractive because

they compensated for or responded to this deprivation.11 A related interpretation found within a number of studies has emphasized continuity between the early True Jesus Church and the native popular religious tradition because of similarities in their charismatic practices and, more generally, their embrace of a world animated by the extraordinary.12

More broadly, scholars of global Pentecostal and charismatic movements have sought to explain why the tongues-speaking mode of charismatic religiosity found within the True Jesus Church also appeared in so many places around the world around the early twentieth century, including China. Again, a common explanation is deprivation: Pentecostal movements grew among poor and marginalized people who suffered “traumatic cultural changes” and “double-barreled disillusionment” with both traditional and scientistic ideologies in the wake of the spread of global modernity.13

Others have countered this emphasis on deprivation by showing that in America, at least, most early Pentecostals “lived comfortably by the standards of their own age.” Instead, they have pointed to Pentecostal converts’ strong desire for personal autonomy in their religious practice.14 Another growing approach to early twentieth-century Pentecostalism emphasizes its geographic diversity, pointing out that multiple Pentecostalisms emerged around the world in centers such as Pyongyang, Korea; Beijing, China; Pune, India; Wakkerstroom, South Africa; Lagos, Nigeria; Valparaíso, Chile; Belém, Brazil; Oslo, Norway; and Sunderland, England. These Pentecostal movements were not isolated from each other but were linked by networks of print and personnel.15 The fact that these numerous Pentecostal movements sprang up around the world around the same time suggests that explanations for the rise of Chinese Pentecostal movements such as the True Jesus Church may go beyond local or national socioeconomic conditions.

I have found the emerging emphasis on transregional analysis very thoughtprovoking in framing my approach to the True Jesus Church. Existing studies have made an invaluable contribution by laying out so clearly the local context of the True Jesus Church (and, more generally, independent Chinese Christian movements). However, as is the case with any study of human experience, including this study, a focus on one set of questions or variables will necessarily leave gaps. By contributing a variety of perspectives, a community of scholars works together to paint a broader picture. In what follows, I lay out my reasoning for exploring other dimensions of charismatic experience within the True Jesus Church in addition to deprivation and continuity explanations. Although this study is primarily a study of the True Jesus Church, my discussion of the limitations of these two approaches also has application for other religious studies