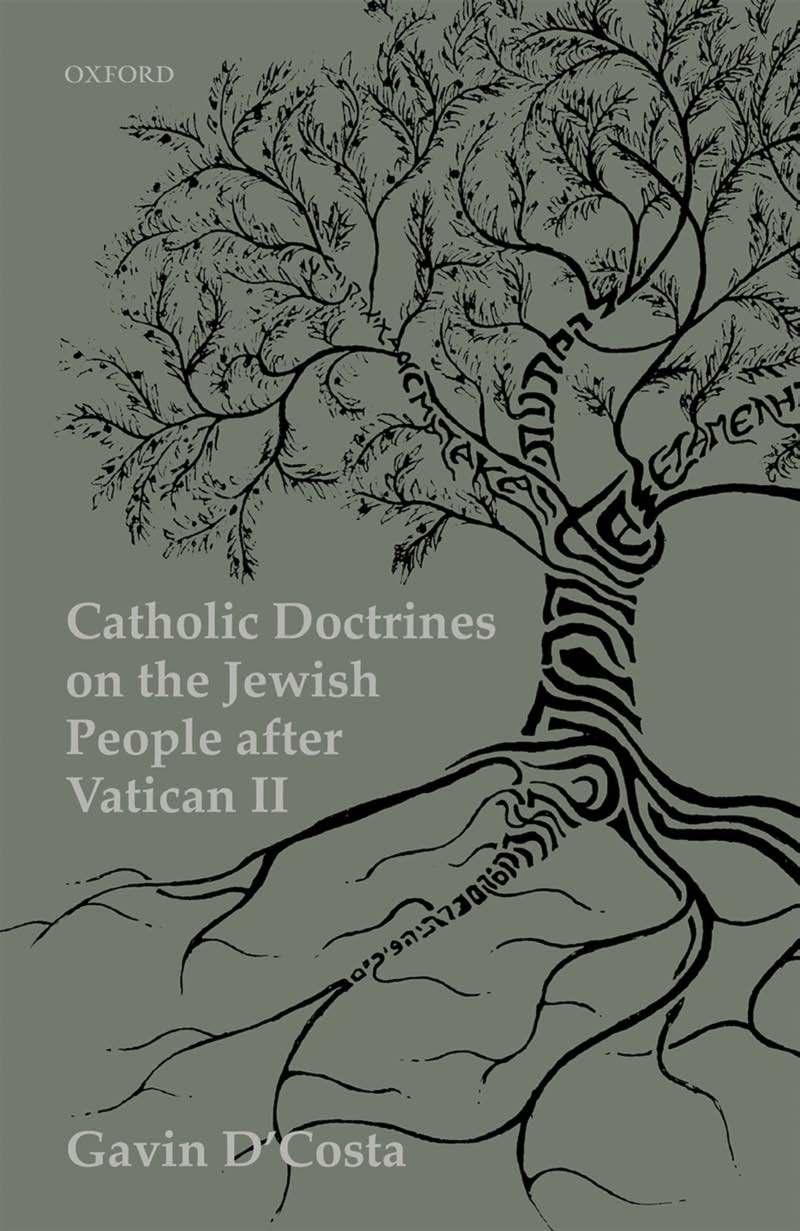

Catholic Doctrines on the Jewish People after Vatican II

GAVIN D’COSTA

1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Gavin D’Costa 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019945678

ISBN 978–0–19–883020–7

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198830207.001.0001

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For: Roshan

Preface

This book presupposes that doctrines matter and doctrines that matter always give rise to further doctrines. Doctrines are fecund. John Henry Newman called this the development of doctrine. He provided rules to discern genuine development and to guard against false doctrines that can act like potassium cyanide uponthebodypolitic.OnecouldneverhavehadthedoctrineoftheAssumption of Mary proclaimed in 1950 without the doctrine of the theotokos, Mary as the Mother of God, proclaimed in 431. One thousand five hundred and nineteen years is a long time for doctrinal development. During that period there were controversies and sophisticated theological disputes. Popular practices, piety, politics, and persecution were also key ingredients. Eventually, the Church ‘proclaims’ on the matter. Rather than that closing the conversation, such proclamationsusuallygeneratefurtherdiscussionandpractice.Andso,thestorycontinues, possiblyuntiltheeschaton.

The pivotal doctrine in this book emerged in the Roman Catholic Church in 1964and1965intwodocumentsfromtheSecondVaticanCouncil,the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, 16, and the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions, 4. Both documents cited biblical grounds: Saint Paul’s teaching in Romans. The doctrine emerged that the covenant God makes with his people, the Jews, is ‘irrevocable’, for God does not go back on his promises and gifts (Romans 11.29). This doctrine took nearly two thousand years to surface actively. It also seemed to run against much theological tradition. It then took sixteen years to develop one step further, through the office of Saint Pope John Paul II in 1980. The development that happened concerned the application of Paul’s teachings in Romans to contemporary Jewry. From the 1980s until 2015 (the cut-off date for this study) the doctrine began to unfold, sometimes with authoritativeteachingsfromthemagisteriumandoftenthroughlessauthoritative teachings; and through the vigorous debate by Catholic, Christian, and Jewish theologians.Thesedevelopmentsgivebirthtofurthertrajectories.Thisbookisan examination of the basic doctrines and the doctrinal trajectories that come into view. All the questions are deeply contested. Some are very new and some as old astheChurch’sexistence.

In Chapter 1, I attend to two questions: the art of reading magisterial documents;andtheemergenceofthedoctrineanditsdevelopment.Isetupthemethodological assumptions of the entire book, showing that the magisterium works

in mysterious, complex, and sometimes unfathomable ways, much like the God whoitsdoctrinalutteringsaresupposedtorepresent.Whilesomanywordshave beenprinted,thereispreciouslittlethatisclearandestablished.However,Iargue that enough is established to begin the task. The second question is then addressed. The magisterium teaches that the covenant with the Jewish people is irrevocable for God is faithful to his promises. It now teaches that this covenant that is found in what I call ‘Rabbinic Judaism’ (Jewish traditions after the fourth centurydrawingontheHebrewBiblebutalsooralTorah),whichisbothcontinuous and discontinuous with ‘biblical Judaism’ (the Judaism of the Hebrew bible/ Old Testament). Not unlike Christianity. If the unrevoked covenant exists in Rabbinic Judaism, what precisely does this mean, even if it sounds like a breathing space from a long history of the persecution of Jewish people? I leave aside a profoundly difficult question: which of the many Judaisms is being referred to, when Jews contest what constitutes Judaism? I propose that at least three further doctrinal questions must be addressed to work out the meaning of these new teachings. Each of these three questions form the substance of the subsequent chapters.Lotsofotherquestionsmighthavebeenasked—andwillbeasked.Ithink thesethreeareunavoidable.

InChapter 2,Iaddressthefirstquestion:thevalueofJewishculticrituals—the prayersandpracticesofdevoutJewsthathave,intheireyes,beendemandedfrom God.TheCatholictraditionseemstohaveadominantculture,establishedbythe twoprominentChurchFathers,SaintsAugustineandAquinas,thattheculticrituals of Jews are ‘dead and deadening’. The Council of Florence (1441) seems to follow this teaching, if not explicitly teach it. The Catholic Church now teaches that by implication these rituals are alive and life giving. Could the Church after nearly one thousand six hundred years teach something that seems to run counter to its great Doctors and Fathers? In principle that is possible. However, could these teachings run contrary to the formal authoritative teachings of a Church council, the magisterium? The usual answer is ‘no’. If councils contain mutually contradictory teachings, then the very foundations of magisterial authority require review. Much is at stake in this issue. Historical honesty, careful exegesis and contextualization of earlier teachings are central to any answer. That answer will also be examined by Jewish scholars who are not wedded to any theories of continuity that Catholic scholars might hold regarding the magisterium. In Chapter 2,Iarguethatthenewteachingsareingenuinedoctrinalcontinuitywith the magisterium. However, non-doctrinal presuppositions undergirding doctrinalutterancesdodiffer.Thishelpsexplainthetensionsthatappearwhenexamining this issue. Chapter 2 affirms that the Catholic Church, without doctrinal contradiction, can affirm that Jewish cultic life is life giving and alive. It still has specific questions that are then generated: which cultic acts? Sacrifice in a third rebuilt temple? All Jewish festivals? In 2015, it proposed (without doctrinal

authority) that through these faithful practices ‘Jews are participants in God’s salvation’.1MoreofthatinChapter 5.

Chapters 3 and 4 are no less controversial and unsettling. I examine a central element of the covenant promise made to the Jewish People: the promise of the land.ItisonethingtosaythatthecovenantwiththeJewishpeopleisirrevocable. It is another matter to say what this amounts to regarding the land promise. Chapter 3 looks at the teachings of the Old and New Testaments to ask whether the promise of the land is still intact in this new doctrinal perspective within Catholicism? Traditionally, the physical claims about the land were transformed into spiritual realities inhering in Jesus Christ and his bride, the Church. The specificboundariesbecomeuniversalized.WiththehelpofthePontificalBiblical Commission, I establish from a Catholic biblical perspective (with no binding doctrinal authority), that the promise of the land by God to his People remains intact, as part of the irrevocable covenant. The New Testament, minimally, does not contradict this. After this clarification of the biblical ground, Chapter 4 then takes another step forward. Does this promise of the land relate to the State of Israel established in 1948? I examine the statecraft of the Holy See and its multifarious organs and its very careful manoeuvring to discern a delicate telos emerging. That telos holds together three theological views: that contemporary Israel has a spiritual significance in God’s love for his Jewish people; that the claims on thelandmustbemediatedbyjusticeregardingthedifferentlylegitimateclaimsof thePalestinianpeople;thatJews,ChristiansandMuslimsallhavespiritualclaims regarding Jerusalem that must be honoured and protected. Within this balance, touching on the first element, emerges what I term a ‘minimalist Catholic Zionism’. ‘Zionism’ does not endorse any form of political Zionism. On the contrary, I use it in fidelity to the biblical view that God acts in history and in time, throughpeoplesandthroughplaces.

Chapter 5 takes up another troubling doctrinal question: is the salvific significance of Jesus Christ being undermined by these newly emerging doctrines? Newman would have smiled at the formulation of the question. No doctrinal development could undermine what is taught with dogmatic certainty through the long history of the tradition. One way of uncomfortably pressing this question is to ask: should there be mission to the Jewish people given the Catholic Church’s teaching regarding the necessity of mission to all those who are unbaptizedanddonotknowthetriuneGod?Thevexingresponseisthattheveryorgan of the magisterium entrusted with putting into practice the teachings of the

1 Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews, ‘The Gifts and the Calling of God Are Irrevocable’ (Rom 11:29)—A Reflection on Theological Questions Pertaining to Catholic-Jewish Relations on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of ‘Nostra Aetate’ (no. 4), 36. Subsequently: ‘Gifts’. <http:// www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/chrstuni/relations-jews-docs/rc_pc_chrstuni_ doc_20151210_ebraismo-nostra-aetate_en.html>. All websites checked August 2018.

CouncilregardingtheJewshassaid,in2015,thatthereshouldbe‘noinstitutional mission’towardstheJewishpeople.2Untanglingandinterpretingtheseutterances is the primary focus of the final chapter. I argue that nothing undermines the irrevocablecovenantthattheJewshavewithGod.Thismustbeaffirmedhumbly, joyfully, and respectfully. However, a new sense of witness is slowly emerging. OnlyaHebrewCatholicecclesia(whatthatsame2015documentcallsthe‘church of the circumcision’3) can witness to the Jewish world the non-threatening good news of the gospel of Jesus Christ. If Jews were to become Catholics, they do not forfeit the promises or the duties of their being the People of the First Covenant. Whether these duties are mandatory on converts is discussed. The theme of Jewish Catholics runs throughout the book. It is unsettling and not always welcome to Catholic–Jewish dialogue, in part because such ‘converted’ Jews are normallyunderstoodasapostates.Sucharethecomplexitiesthatinevitablyunfoldas difficultquestionsareexplored.

I make no claim that the Catholic magisterium supports the answers developed in this book. Rather, I claim that the authoritative and non-authoritative teachingsofthemagisteriumanditsorgansopentrajectoriesthatmightbeinterpreted to point towards the solutions proposed in this book. Only time and theologicaldebatewilljudge.

Chapter 6 is a systematic summary of the positive findings of this book. It is offered as one more tentative step towards the Catholic Church discovering its own ecclesial nature, which poses challenging questions to itself. At the same time, it allows it to slowly move into a more repentant, humble, positive, and learning space to engage with the Jewish people, knowing that Judaism emerges from the divine source that nourishes the Catholic Church itself. If the Catholic ChurchfailstoseeinJudaismthewaysofGod,shefailstorecognizeherself.

2 Gifts, 40. 3 Gifts, 15.

1 The Catholic Doctrine of God’s Irrevocable Covenant to the Jewish People

Introduction

One single question lies at the centre of this book. If the Catholic Church teaches that the covenant that God has made with his people, the Jews, is irrevocable, what does this mean for Catholic theology regarding the Jewish people? The question presupposes that the Catholic Church promulgates this teaching. I believe that it does. I will turn to justifying this claim below.

Since the fourth century the attitude on three doctrinal questions arising from the assumption that the Jewish covenant has been revoked began to develop in mainstream theological culture. The Jewish people had been superseded, that is, the covenant God made with the Jewish people was null and void. The gifts and promises made to Israel were transferred to the new Israel, the Church. Old Israel had been discarded because the Jewish people had been unfaithful to their covenant in rejecting their messiah. However, the Jews still served a purpose—within Christian theology. The story was not entirely negative. Augustine and the mainstream subsequent tradition developed various theories that their purpose was to unwittingly testify to Christian truth.1 For this reason, the Jewish people had a special place in salvation history, despite their being punished by God because of their infidelity. They were treated with varying degrees of contempt by Christians, including active persecution, but sometimes with respect.2

What were the three doctrinal questions whose answers led to the conclusion: the Jewish covenant was revoked? The first relates to the cultic ceremonial rituals

1 See the nuanced studies by Lisa A. Unterseher, The Mark of Cain and the Jews: Augustine’s Theology of Jews and Judaism (Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2009) and Paula Fredriksen, Augustine and the Jews: A Christian Defense of Jews and Judaism, 2nd edn (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2010). It is beyond my remit to deal with the many readings of Augustine—and Aquinas—on this matter.

2 See Edward H. Flannery, The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism, rev. edn (New York: Paulist Press, 1985).

Catholic Doctrines on the Jewish People after Vatican II. Gavin D’Costa, Oxford University Press (2019).

© Gavin D’Costa.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198830207.001.0001

of the Jewish people.3 The argument ran something like this: since the Jews were guilty of deicide they deserved the punishments that befit such a crime. The first implication of their crime is that they are cursed. Their religion is null and void. Their cultic ceremonies were ineffective now that the messiah, to which all ritual life had been oriented, had come in the person of Jesus. Prayers that looked forward to the messiah’s coming could serve no purpose after he had arrived. In fact, saying these prayers was a form of heresy for they denied the truth of Jesus as messiah. The destruction of the temple in 70 ad was testimony to the ‘end’ of the Jewish cultic religion. Nevertheless, Jewish cultic practices still had the benefit of honouring the Old Testament4 and publicly pointing to the messianic hope—that was realized in Jesus Christ. This teaching about the ineffective religious ritual life of the Jews was established by Augustine and reinforced by Aquinas, with complex caveats as befits such fine theologians. Aquinas taught that Jewish ceremonies were dead (mortua) and deadening (mortifera). These presuppositions entered into the formal teachings of the Catholic Church at the Council of Florence in the Bull, Cantate Domino (1441).

Roughly five hundred years later, Vatican II (1963–5) was the beginning of a re-evaluation of the deicide charge in terms of formal Council teachings.5 The Catechismus Romanus (1566), often called The Tridentine Catechism as it was commissioned by the Council of Trent (1562), had already signalled an alternative understanding. The Catechism acknowledged that historically Jews had crucified Jesus. However, it taught that ‘the principal reason’ for the crucifixion was ‘sin, the original sin passed down from our first parents, and then all the possible sins which men have committed from the very beginning right up to the present and which will be committed up to the end of the world’. It argued that Christian sins: ‘seem graver in our case than it was in that of the Jews; for the Jews, as the same Apostle says, “would never have crucified the Lord of glory if they had known him” (1 Cor. 2.8). We ourselves maintain that we do know him, and yet we lay, as it were, violent hands on him by disowning him in our actions.’6

3 This distinction, ‘ceremonial’ laws, is drawn from Aquinas’ tripartite distinction between the three aspects of the Mosaic law. In Aquinas, Summa Theologica (Blackfriars translations published by Blackfriars/Eyre & Spottiswoode, London/McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1963–1966), 2a, q.99, a.4 he states: ‘We must therefore distinguish three kinds of precept in the Old Law; viz. “moral” precepts, which are dictated by the natural law; “ceremonial” precepts, which are determinations of the Divine worship; and “judicial” precepts, which are determinations of the justice to be maintained among men.’ This is a heuristic device to isolate aspects of the question and will not necessarily be acceptable to Jewish thinkers, past or present.

4 I retain the term ‘Old Testament’ as this is the current usage in official Catholic documents. It is not meant pejoratively.

5 For a detailed account of the Council on this matter see John M. Oesterreicher, The New Encounter: Between Christians and Jews (New York: Philosophical Library, 1986) and Augustin Bea, The Church and the Jewish People. A Commentary on the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions, trans. by Philip Loretz (London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1966).

6 English translation of The Tridentine Catechism, from John A. McHugh, O.P. and Charles J. Callan, O.P. (1923), at: <http://www.angelfire.com/art/cactussong/TridentineCatechism.htm>

The Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions, Nostra Aetate, No. 4 (1965), took the further step of disassociating the deicide charge from all Jews during the time of Jesus and subsequently throughout history:

the Jewish authorities and those who followed their lead pressed for the death of Christ; still, what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today. Although the Church is the new people of God, the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures.7

This offered a nuanced commentary on the biblical verse uttered by the ‘crowd’ in the passion narratives. Violence against Jews after Easter liturgies is well documented. After all, many believed the Jewish people cursed themselves: ‘His blood be on us and on our children!’ (Matthew 27:25).8 No longer could this curse apply to all the children of Israel after Vatican II. There is recognition that the lifting of the deicide charge would have repercussion upon the status of Jews today. If they were not ‘rejected or accursed’, what were they? Nostra Aetate offered the same answer as the earlier and more authoritative document from the Council, the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium (1964) 16:

In the first place we must recall the people to whom the testament and the promises were given and from whom Christ was born according to the flesh. (Romans 9:4–5) On account of their fathers this people remains most dear to God, for God does not repent of the gifts He makes nor of the calls He issues. (Romans 11: 28–9).

The Jews were ‘most dear to God’ for the theological reasons given by Paul: God does not repent of the gifts and calls He issues. He promises to be faithful to his people and the gifts he makes to them constitute his covenants to them. Nostra Aetate repeats the exact phrase from Romans 11:28–9. This phrase would form the title of the 2015 anniversary document published by the Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews: ‘The Gifts and the Calling of God Are Irrevocable’ (Rom 11:29)—A Reflection on Theological Questions Pertaining to Catholic-Jewish Relations on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of ‘Nostra Aetate’ (no. 4)9 (Gifts). The emerging Catholic teaching was based on scripture being slowly unfolded. While it was clear that the Council had repudiated the deicide charge as an undifferentiated ‘guilt’ upon the entire Jewish people, the theological status of

7 All Conciliar texts taken from the Vatican website English translation, unless otherwise indicated.

8 All scriptural quotation taken from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, unless otherwise indicated.

9 <http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/chrstuni/relations-jews-docs/rc_pc_ chrstuni_doc_20151210_ebraismo-nostra-aetate_en.html>. All website checked August 2018.

contemporary Jewish people, what I call Rabbinic Judaism, was far from clear in the Council documents. Considerable debate ensued on this matter. Some theologians argued that the Council did not apply this Pauline teaching to Rabbinic Judaism but only to biblical Judaism, while others argued that the application was implicit but clear.10 Only in 1980 did Pope John Paul II utilize Romans 11:29, applying it to an audience of Jewish dignitaries in Mainz, Germany. After that, the teaching has been reiterated through two subsequent papacies (Popes Benedict XVI and Francis), the Catholic Catechism, and in numerous documents from the Commission for the Religious Relations with the Jews. More on this below. The Commission also clarified that this teaching was not to be found in the sometimes ‘over-interpreted’ readings of the Council texts but began with the Pope’s speech in 1980.11

If the covenant with the Jews is irrevocable, does it mean that nearly sixteen hundred years of mainstream Christian theological tradition is over-turned regarding Jewish religious ritual? Further, if older theological traditions were implicit or explicitly present in formal Council teachings, as it seemed in both the Second Lateran Council (1139) and the Council of Florence (1441), could such teaching be overturned by a later Council if they involved matters of doctrine? After the Second Vatican Council a small number of Catholics feared that the positive moves made by the Council towards the Jewish people undermined authoritative earlier Conciliar teachings. They argued that Florence clearly taught that the Jews were damned and that their religious rites were dead and deadly.12 These Catholics, who eventually went into schism, called into question the authority of all the popes since Paul VI who had presided over the main part of Vatican II. The question is primarily an internal doctrinal disputed question; and secondarily, an important question for Catholic—Jewish relations.

The second doctrinal question treated in this book is sometimes not viewed as doctrinal. I believe that it is. It is based in scripture and its appropriate application

10 For the former, see my, Vatican II: Catholic Doctrines on Jews and Muslims (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 122–51; for the latter, see for example: Michael McGarry, ‘Can Catholics Make an Exception? Jews and the New Evangelization’, 1994; Marianne Moyaert and Didier Pollefeyt, ‘Israel and the Church: Fulfilment beyond Supersessionism’, in Never Revoked: Nostra Aetate as Ongoing Challenge for Jewish-Christian Dialogue, eds. by Marianne Moyaert and Didier Pollefeyt (Leuven; Walpole, Mass.: Peeters, 2010), 159–85; and note 123 of D’Costa, ibid, contains further bibliographical references.

11 Gifts, 39: ‘Because it was such a theological breakthrough, the Conciliar text is not infrequently over–interpreted, and things are read into it which it does not in fact contain. An important example of over–interpretation would be the following: that the covenant that God made with his people Israel perdures and is never invalidated. Although this statement is true, it cannot be explicitly read into Nostra Aetate (no. 4). This statement was instead first made with full clarity by Saint Pope John Paul II when he said during a meeting with Jewish representatives in Mainz on 17 November 1980 that the Old Covenant had never been revoked by God.’

12 See for instance Marcel Lefebvre, I Accuse the Council!, trans. by Jaime Pazat de Lys, 2nd edn (Kansas City, Mo.: Angelus Press, 1998); Michael Davies, Pope John’s Council (Kansas City, Mo.: Angelus Press, 1977).

to post-biblical realities. It tells us about who God is and how God acts. It is the question regarding the promises and covenant as they bear upon ‘the land’, Israel as a land for God’s people. The old argument ran something like this. Since the Jews forsook Jesus Christ their messiah, they were cursed. One element of this curse related to another aspect of the covenant promise, the land. Soon after the temple’s destruction in 70 ce, the Jewish dispersion began that was ‘completed’ after the second Jewish revolt in 132 ce that was decisively crushed by Hadrian. Hadrian exiled the Jews and forbade their living in Jerusalem. The curse tradition was already implicit in the Genesis (4: 11–16) story of Cain for the wrongful murder of his brother Abel. He was cursed: ‘you shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth’. A similar curse was pronounced upon disobedient Jews in Hosea 9: 17: ‘My God will reject them because they have not obeyed him; they will be wanderers among the nations.’ The wandering Jew tradition can be traced throughout Christian history but became consolidated in the middle ages and took on many regional variants.13 Underlying it was the assumption that the Jewish people had irrevocably lost their land.

After the Holocaust/Shoah, when Jewish safety in Europe was dealt a mortal blow, the pre-war mainly secular Zionist movement gained huge momentum. Given the terrible suffering of the Jewish people in the Holocaust more religious Jews became aligned to the Zionist movement. The story is complex and has very different narrative versions (Marxist, nationalist, secular Jew, religious Jew, Christian Zionist, Christian supersessionist). Christian Zionist versions were also central in the establishment of the Jewish homeland.14 Leaving aside the difficult historical questions regarding the causality and international legal questions behind the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, legitimated by the 1947 United Nations declaration, what emerged was a Jewish homeland for Jewish people in a Jewish state—that had in its foundation charter a place for Arab and non-Jewish peoples. The theological question of the biblical land promise once more returned. It returned at the very time the churches, including the Catholic Church, were beginning to reread Paul and their own early foundation stories. It returned when a number of Protestant groups had rejoiced in the foundation of Israel and saw this event as heralding the ‘end days’. Many of these groups were also hostile to Palestinian claims on the land. The difficulty of disentangling the theological and political is acute.

The doctrinal question is this: if the land was part of the covenant that God makes with his people, the Jews, and the covenant is irrevocable, then does that

13 See for example Ann Matter, ‘Wandering to the end: The medieval Christian context to the wandering Jew’, in Transforming Relations : Essays on Jews and Christians throughout History in Honor of Michael A. Signer, ed. by Franklin T. Harkins (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), 224–40.

14 For an interesting overview of differing constructive narratives, see Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Land of Israel: From Holy Land to Homeland, trans. by Geremy Forman (London: Verso, 2014).

promise still stand? That is a doctrinal question based on biblical teaching. If it does stand, does it apply to post-biblical Israel (of 1948). This concerns the application of doctrinal teaching. The Catholic Church has walked a very delicate tightrope and possibly a very crooked one on this matter. Before its doctrinal teachings on the covenant were developed, it resolutely opposed any form of Zionism for the promises and covenants now belonged to the Church. After Vatican II, it slowly accepted the legal right of Israel to exist in tandem with the legal rights of Palestinians to a homeland. It has gently and delicately skirted answering the theological question directly. This is partly because it is a difficult theological question. It is also because of the political minefield surrounding the issue. If answered affirmatively, the Eastern Churches, Palestinian and Arab hostility would be powerful; if answered negatively, the Jewish hostility and disappointment would be considerable. However, the doctrinal question will not evaporate: is the State of Israel related to the promise of the land made to the Jewish people? ‘Yes’, ‘no’, ‘don’t know’ are better than a silence on the matter.

The third doctrinal question in the book concerns ‘mission’. In Matthew 10: 5–6, Jesus tells his twelve disciples: ‘Go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.’ Other New Testament texts testify to Jesus teaching a universal mission: ‘Go into all the world [kosmon] and preach the gospel [euangelion] to all creation [ktisei].’ (Mark 16: 15).

Behind both traditions stands a more primary one, which is seen as central to Catholic dogma (a doctrine that is formally understood to be irrevocably true): Jesus Christ is the saviour of the world, sent by God for the redemption of all.

However, if the Jewish covenant given by God is irrevocable, is mission to the Jewish people still valid? If the true God has accompanied his people, irrevocably committing Himself through His covenantal love, are these a people who need to find the true God? They worshipped the true God before Jesus Christ and after Jesus Christ. At Vatican II, in the document Ad Gentes literally translated To the Gentiles (The Decree on the Missionary Activity of the Church, 1965) we find the call to universal mission. However, some theologians argue this missionary necessity was addressed to the ‘gentiles’, as seen in the document’s title, not to the Jewish people. They argue there is no call to evangelize the Jewish people in the Council. In fact, the Council dropped a sentence in an earlier draft of Nostra Aetate on this very issue, indicative that there were serious reservations by the fathers.15 In 2015, Gifts finally explicitly addressed the question. It contained these words:

The Church is therefore obliged to view evangelisation to Jews, who believe in the one God, in a different manner from that to people of other religions and

15 See Giovanni Miccoli, ‘Two Sensitive Issues: Religious Freedom and the Jews’, in History of Vatican II. Vol. 4 Church as Communion: Third Period and Intersession, September 1964–September 1965, eds. by Giuseppe Alberigo and Joseph A. Komonchak (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2003), 95–194.

world views. In concrete terms this means that the Catholic Church neither conducts nor supports any specific institutional mission work directed towards Jews....there is a principled rejection of an institutional Jewish mission...16

Predictably there were headlines in the American and Israeli press. The New York Times ran the story: ‘Vatican Says Catholics Should Not Try to Convert Jews’.17 The Times of Israel fronted the story: ‘Vatican calls on Catholics to stop trying to convert Jews. Declaration asserts Jewish people can be saved without converting, urges Christians to work with them to fight anti-Semitism.’18 The salvation of the Jewish people, who required no conversion, was picking up from Gifts’ claim: ‘That the Jews are participants in God’s salvation is theologically unquestionable...’19 Catholic theologians who supported these headlines argued that since the Jewish covenant was with the true and living God, the Father of Jesus Christ, Israel was an ‘exception’ to the rule of mission to all peoples and nations.20 Hence, there are two doctrinal issues at stake here: the universal salvific efficacy of Jesus Christ; and the mission to evangelize all women and men. If the Jewish people can be saved within Judaism does it mean yet another doctrinal overturning, another abandonment of the patrimony of the faith?21

These three doctrinal questions will be the primary focus of this study. The first concerning Jewish cultic ritual will be treated in Chapter 2. The second on the land will be taken up in Chapters 3 and 4. The question of mission will be addressed in Chapter 5. In the remaining part of this chapter, I will establish that the Catholic Church does teach that the covenant to the Jewish people, made by God, is irrevocable. I then establish that this applies to Rabbinical Judaism. Before that, a word on methodology and the different types of magisterial documents I inspect. These documents establish what the Church teaches, how authoritatively, and what trajectories appear as possible answers to questions the teachings raise.

Methodology and Magisterial Authority

In a previous book, where I sought to establish the doctrinal teachings of Vatican II on the Jewish people, it became evident that the magisterium’s authority was

16 Gifts, 39.

17 December 10, 2015, at: <https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/11/world/europe/vatican-sayscatholics-should-not-try-to-convert-jews.html>

18 <https://www.timesofisrael.com/catholic-theologians-say-jews-can-be-saved-without-converting/>

19 Gifts, 36. 20 McGarry, ‘Exception’.

21 Those in schism already cited—see above, p. 4 n.12 For Catholics, see for example: William B. Goldin, ‘St. Thomas Aquinas and Supersessionism: A Contextual Study and Doctrinal Application’ (Angelicum, Rome: PhD Thesis, 2017); Douglas Farrow, Theological Negotiations: Proposals in Soteriology and Anthropology (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2018), see chapter, ‘For the Jew First’. See an interesting schismatic portrayal of this issue: <https://novusordowatch.org/2015/12/ the-kosher-church/>

definitive for moving the issues to centre stage.22 After the Council different groups (theologians, committees, papal dicasteries, ecumenical groups, Jewish partners and communities, and secular media outlets) began to critically engage with the Council teachings. There was schism in the Catholic Church, partly over this matter. The reception of the Council is a complex and messy question that requires the kind of historiography, but perhaps with a different theological persuasion, to the momentous achievement of Alberigo and Komanchak’s History of Vatican II.23 My book is one of the many interpretative attempts to listen to the voice of the teaching church, attend to the signs of the time, while engaging in conversation with Jewish and Catholic scholars to advance the project of Catholic theological reflection on the Jewish people.

In every chapter I pay attention to one teaching voice of the church in particular, the magisterium, to note developments, trajectories, and innovatory reflection upon ancient sources to engage with the Jewish world in fidelity to Jesus Christ. In my previous book, one of my main arguments was that the novelties and developments of doctrinal teaching at Vatican II were not doctrinally discontinuous with previous authoritative teachings. In this book, that focus will not be central because the teachings examined do not have the same authority as those at the Council. Rather, in this book I trace the impact of post-conciliar theology in terms of engaging with the three questions stated. Nevertheless, the authority weighting of church documents is critical to understanding their force, both in their prohibitions of certain positions and in their encouragement of and inviting new research. For instance, Gifts, published in 2015 by the Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews has no doctrinal status, even though it comes from a Pontifical dicastery entrusted to implement the Church’s teaching. It also involved input from the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith.24 However, the opening preface states its authority:

The text is not a magisterial document or doctrinal teaching of the Catholic Church, but is a reflection prepared by the Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews on current theological questions that have developed since the Second Vatican Council. It is intended to be a starting point for further

22 See Vatican II, 113–59.

23 The English translation published by Orbis Book, Maryknoll, New York and Peeters Leuven between 1995–2006. Regarding its theological bias see Agostino Marchetto, The Second Vatican Ecumenical Council: A Counterpoint for the History of the Council, trans. by Kenneth D. Whitehead (Scranton, Pa.: University of Scranton Press, 2010).

24 See Norbert Hofmann, ‘On the birth of the document’, at the formal presentation of the doctrine: ‘From the beginning there has been close collaboration with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which is of course always consulted when it comes to Vatican theological texts. In this regard, we would like to thank His Eminence Cardinal Gerhard Müller and his staff for their expertise and availability in this joint work.’ <https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/it/bollettino/pubblico/ 2015/12/10/0976/02131.html>. It is interesting that the document contains no co-attribution as does Dialogue and Proclamation

theological thought with a view to enriching and intensifying the theological dimension of Jewish–Catholic dialogue.

I will briefly catalogue the types of documents I draw on, and their authority.25 This will indicate both the solidity or otherwise of the base and the super-structure from which my constructive arguments are developed. The danger of ignoring the question of authority in differing levels of Vatican teaching easily leads to the highly misleading reporting found in The New York Times and The Times of Israel cited above. They portray Gifts’ teachings as having authority over Catholics because they come from ‘the Vatican’—despite the opening qualification of the document denying this. Journalists can perhaps be forgiven overlooking such ‘fine points’; scholarship cannot.26

The pope on his own in ex cathedra form (when speaking alone) or with a Council can pronounce a solemn definition of the faith (de fide definita). This constitutes the highest level of authority, but the definition still requires interpretation. The Council and pope together represent the highest court of authority in the universal church. The 1985 Synod of Bishops provided a guide on how to read the Council documents. Dogmatic Constitutions are of the highest order; Declarations were employed to illustrate and further reflect on the Dogmatic Constitutions.27 Whether a Declaration could contain doctrinal teaching that was not found in a related Dogmatic Constitution became moot. However, not everything in a Dogmatic Constitution contained binding doctrinal teaching. When it does, it usually indicates this through the type of solemn phrase found in Lumen Gentium 14: ‘Basing itself upon Sacred Scripture and Tradition, it teaches that the Church, now sojourning on earth as an exile, is necessary for salvation.’ This is the highest level of teaching authority being signalled: it is found in scripture, in the tradition, and is being proclaimed by the magisterium in a Dogmatic Constitution. One must recall that the magisterium can only teach what it has been given in scripture either explicitly or implicitly. It has no authority outside of the deposit

25 See two helpful accounts regarding the authority of differing types of Vatican documents: Avery Dulles, Magisterium: Teacher and Guardian of the Faith (Naples, FL: Catholic University America Pr, 2013); Francis Aloysius Sullivan, Creative Fidelity: Weighing and Interpreting Documents of the Magisterium (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1996). Part IV of Richard R. Gaillardetz, By What Authority?: Foundations for Understanding Authority in the Church, 2nd edn, rev. edn (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press Academic, 2018) emphasizes the role of the believing community’s authority. Lumen Gentium, 25 addresses this question in quite traditional terms.

26 The status of Council documents are themselves contested. See Ilaria Morali, ‘Interview with Zenit’, Zenit, 2005 <https://www.ewtn.com/library/Theology/ZINTEREL.HTM>: Nostra Aetate ‘only gave guidelines of a practical order on the specific relationship between the Church and members of other religions. [It] was conceived as a practical appendix to the lines dictated by “Lumen Gentium” and more generally of conciliar ecclesiology. Whoever today in the ecclesial and theological realm tends to forget “Lumen Gentium” and to attribute a doctrinal value to the “Nostra Aetate” declaration falls, in my understanding, into great ingenuousness and historical error.’

27 <http://www.ewtn.com/library/CURIA/SYNFINAL.HTM>. 1.5. I only mention the two types of documents utilized in this study. There are Decrees that rank above Declarations.

of faith. Tradition helps the unfolding of scripture. Implicit teachings of scripture are more controversial, even when some traditions support an implicit teaching. This was evinced in the magisterium’s definitions of the Immaculate Conception in 1854 and the Assumption of Mary in 1950. What was proclaimed, it was argued, was always implicit in scripture and became explicit through church devotional practices.

After the Council, teachings about the Jewish people came from four main sources: Popes, Pontifical Councils, Congregations, and in some instances, Secretariats. These are offices within the Vatican that assist the Pope in his teaching office and in the implementation of Conciliar teachings. The Vatican is a city state with diplomatic relations with other states conducted through the Secretariat of State. The type/genre of document each group produces have different levels of authority. While some of the distinctions I draw are contested, I will elaborate on critical debates regarding the authority of various teachings in the body of the book when those documents are introduced. I will not usually deal with the output of national bishops’ conferences. The authority of their teachings on doctrinal matters has been contested.28 Their teachings clearly have some application within their area of jurisdiction, the national church in question. What they show is how national churches evolve and develop doctrinal insights that may or may not be received within the wider church.29

The main papal teachings about the Jewish people come from different types of text, in their order of weight: Encyclicals, Exhortations, Constitutions, Letters, occasional speeches and allocutions, and legal judgements (motu proprio). Exhortations usually contains formal doctrinal teachings but will also depend to whom they are addressed. Exhortations have usually followed Synods of Bishops and represent the mind of the bishops and can contain doctrinal matters. The larger the Synod in terms of representation, the greater its authority, but formally it cannot teach without the Pope on matters of doctrine. The other types of documents do not normally contain doctrinal teachings per se although they might reiterate doctrinal teachings and apply them to new contexts. One must judge ad hoc, taking consideration to whom it is addressed and the context of the teaching. Sometimes the texts of speeches are used in an encyclical or even a Council so they may eventually enter formal teaching status. This was the case with Paul VI’s

28 Dulles, Magisterium, 54–7 argues they have none. Alexander M Laschuk, ‘Assemblies of Hierarchs and Conferences of Bishops: A Comparative Study’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Saint Paul University, Canada, 2016), after an extensive survey of differing views comes to a different conclusion—limited authority.

29 Pope Francis has systematically begun to include references to Bishops Conferences in his writings addressed to the universal church. Evangelii Gaudium (2013) cited the Latin American bishops fifteen times, the US and French bishops twice, and the bishops’ conferences of India, Brazil, Philippines, Congo, and the European Bishops’ Conferences. This is not to be found in any other postconciliar pope. See also his Apostolic Constitution, Episcopalis Communio (2018) that views synods as listening and teaching and widens their voting base to include (male) laity.

teaching on Islam.30 At other times papal teachings enter the Catechism that indicates a consolidated teaching that is part of the universal church’s belief. Catechisms do not propagate or develop new teachings. Sometimes speeches contain teachings that are repeated frequently and so gather authority by their constant repetition. As we shall see shortly, these last two categories relate to the status of the teaching that the covenant with the Jewish people is irrevocable and is thus applicable to Rabbinic Judaism. The Council achieved the first part of this claim and Pope John Paul II begins the momentum related to the second claim. It is not an infallible or irrevocable statement as it stands but its continued repetition by three popes means that one should reflect on it and unpack its significance. Perhaps in the future it will be registered as a formally taught doctrine. Finally, when the Pope issues a motu proprio, this is a legal enactment by the Pope’s own authority and can be used for a variety of purposes. It can set up a new pontifical council or make minor changes to canon law or modify parts of the liturgy.

The offices within the Vatican assist the Pope and the college of bishops in their ministry. Avery Dulles summarizes the scope and function thus:

Besides teaching in his own name, the pope may teach through dicasteries of the Roman Curia: the Secretariat of State, the congregations, tribunals, offices and commissions. The prefects and members of the congregations are cardinals and bishops. Appointed by the pope, they serve at his pleasure as a kind of cabinet.

The acts of congregations, though not issued in the name of the pope himself, gain juridical authority by being approved by him either in a general way (in forma communi) or specifically (in forma specifica). In the latter case they are equivalently acts of the pope himself. Official teachings of the Holy See normally come into force after publication in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis.31

The main doctrinal teaching office is that of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (subsequently: Doctrine of the Faith). It was founded in 1542 as the Office of the Inquisition. It was called the Holy Office from 1908 until 1965. After the Council, its new name was introduced. It is uniquely charged with protecting, clarifying and teaching doctrines and morals.32 Of all the dicasteries, it alone can authoritatively teach on doctrinal matters and can also intervene with the force of

30 This is excellently documented in Andrew Unsworth, ‘A Historical and Textual-Critical Analysis of the Magisterial Documents of the Catholic Church on Islam: Towards a Hetero-Descriptive Account of Muslim Belief and Practice’ (unpublished PhD, Heythrop College, London, 2007).

31 Dulles, Magisterium, 53–4.

32 John Paul II, in the Apostolic Constitution Pastor Bonus (1988) 48, specifies the responsibilities and norms governing the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, ‘to promote and defend the doctrine of the faith and its traditions in all of the Catholic world’. This means it can authoritatively teach doctrine. It lays out the different degrees of teaching in Professio Fidei (1998) and the Instruction Donum Veritatis (1990). This hierarchy of degrees should not be considered an impediment but a stimulus to theology.