1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–084603–9

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For Emma

1. Animals as Persons: The Very Idea 1

2. The Ghost of Clever Hans 26

3. Consciousness in Animals 47

4. Tracking Belief 64

5. Rational Animals 85

6. Beyond the Looking Glass 107

7. Pre-Intentional Awareness of Self 127

8. In Different Times and Places 146

9. Self- Awareness and Persons 165

10. Other- Awareness: Mindreading and Shame 176

11. Animals as Persons and Why It Matters 194

Bibliography 201

Index 211

Preface and Acknowledgments

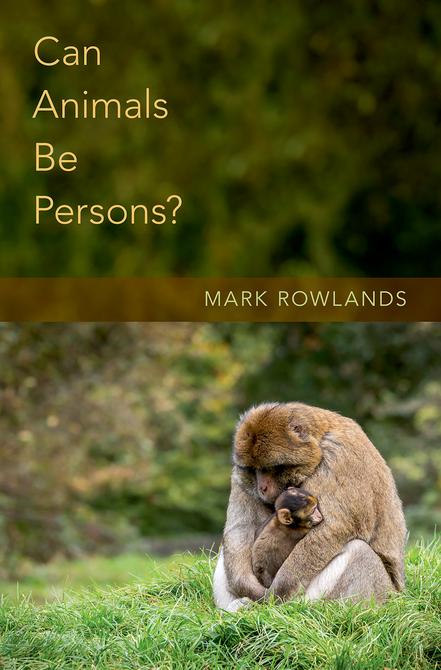

Animals, Claude Levi- Strauss once suggested, are both good to eat and good to think. I assume he had nonhuman animals in mind, and I shall adopt the common practice of using the word animal to refer to the entire swathe of living, non- sprouting, nonhuman forms of life. Some find the idea of categorizing such a large segment of the earth’s biota solely in terms of their not being humans to be a little egotistical on the part of humanity. They may well have a point. Moreover, it can be the source of various logical confusions. Descartes once argued that animals could not have immortal souls because if we granted that one species of animal possessed such a thing, we would have to grant souls to all species— the humble sponge was the animal he cited as a reductio of this idea. I assume there is no need to point out how ridiculous is this argument. “Animal” does not pick out a natural biological kind—any more than “living things that have been in my kitchen” would pick out such a kind. However, as conceited, logically pernicious, and biologically gerrymandered as it may be, I cannot think of any other label that will get through the sheer amount of work as the word animal. Thus, in this book, I shall use animal in the way explained above.

I agree with Levi- Strauss: the living, nonhuman and non- sprouting segment of the natural world can be both good to eat and good to think. The former pleasures have long been denied me: essentially by myself—a protracted, occasionally unsuccessful exercise in self-denial. In reality, I have little choice. You write a book

x Preface and Acknowledgments

or two defending the idea of animal rights, and no one is going to let you forget it, believe me. Thus, I have to console myself with the other use of animals— tools for thinking, food for thought. I think it might have been Hugo— canine, co- father, cosmopolitan, world- traveler, someone I was fortunate to know for almost all of his life— who first got me started thinking about this question of animal personhood. You see, not only was I convinced he was a person, but I was pretty sure he was a better person than I.

There is an inconvenient principle that seems to have sunk its claws into me over the years, one by which my thought has slowly become tainted: all things being equal, brute, lived reality should always trump philosophical theory. Such reality should, at the very least, always be given the benefit of the doubt. I spent a lifetime with this dog, Hugo, and I came to know that he is a person—a unified subject of a mental life. I say I knew this, but what I mean is that I could not doubt it. Not in my life. My attitude toward him was, as Wittgenstein once put it, an attitude toward a soul. On the other hand, I see theories of personhood that tell me he cannot be a person. I can only conclude—as a preliminary operating assumption, an assumption that may, of course, ultimately prove to be mistaken— that perhaps, just perhaps, these theories need a little looking at. That is what I have done. I know, I know: the foregoing tenses are all messed up—is/was/know/knew. Hugo died when I was writing this book. He now lives on only in memories and dreams. And maybe, just a little, in the book too.

As with all of my books about animals, this is as much as book about humans. Indeed, it may even be more of a book about humans than animals. The four central pillars of the book are consciousness, rationality, self-awareness, and otherawareness. These, I shall argue, are core constituents of the person: a person is something in which these four features coalesce. The ostensible question is whether animals have each of these features. But discussion of the question, in turn, highlights what each of these things are and what it means for humans to have them.

The title of this book is a riff on an earlier book of mine, also published by OUPNY a few years ago: Can Animals Be Moral? The present title is not entirely adequate. Of course, animals can be persons—if they satisfy the appropriate conditions of personhood. The real question is whether any—nonhuman—animals are persons. I am going to argue that, in all likelihood, many are. I am enough of a realist to know that, in many circles, this conclusion will not be unduly popular. The depths of my anticipated unpopularity, however, may not be plumbed by the book’s central contention alone. I can imagine even those who might be sympathetic to this contention being displeased with certain other facets of the book. For example,

Preface and Acknowledgments xi those of you engaged in the scientific study of animal minds—many of you I am proud to call my friends— the last thing you probably want to hear is: “What you need is more Kant!” Who, a few masochists aside, would want to hear that? Nevertheless, it is what it is. If this book is correct, some level of acquaintance with the Critique of Pure Reason might be beneficial for anyone engaged in the scientific study of animal minds. Life can be cruel sometimes.

I’m also surprised by the sheer amount of phenomenology that found its way into the final drafts of this book. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised. This sort of stuff has been progressively encroaching on my work over the years, and I don’t seem to be able to do a damned thing about it. But, more than that, perhaps it is natural and appropriate. Phenomenology is the study of lived experience and the structures of consciousness that make such experience possible. It is very difficult, these days, to doubt that animals have conscious experience. A few decades ago it was easier, I’m told. But now, forget it. The more cognitively sophisticated mental activity becomes, the more people are tempted to deny it of animals. But experience— that’s near the bottom of the sophistication scale, or so many think, and so therefore one of the easier things to suppose animals have. Thus, it is natural that a science—and that is how phenomenology presented itself—of lived (lived, not dead) conscious experience should play a significant role in this book.

I would like to thank Kristin Andrews and David DeGrazia, readers for OUP, whose feedback helped make this book much better than it would otherwise have been. The shortcomings that remain are, of course, entirely my fault. An earlier incarnation of the arguments developed in Chapters 6–8 appeared as a target article in the journal Animal Sentience. I am grateful to all who responded to this article. I inflicted many of the ideas of this book on students— sufficiently misguided to enroll in a graduate seminar I taught in the spring of 2017 and sufficiently kind to supply some very helpful comments. My thanks to Henry Arrowood, Elizabeth Cantalamessa, Lou Enos, Justin Hill, Dogan Kazakli, Arturo Leyva, John Odito, and Vedant Singh.

My greatest thanks are, as always, to my family. To my wife, Emma. And to my sons, Brenin and Macsen, who are a constant inspiration. It’s all over for me, of course, but I am going to enjoy living vicariously through you for a while. No pressure.

Can Animals Be Persons?

1

ANIMALS AS PERSONS

The Very Idea

1. The Uses and Abuses of the Merriam-Webster Dictionary

The idea that any nonhuman animal (henceforth, adopting a common if contentious practice, “animal”) could be a person appears—prima facie to be utterly confused. A quick perusal of my Merriam-Webster seems to confirm this. It defines persons in three different ways. First, a person is “a character or part in or as if in a play.” This definition, I have to say, does not seem obviously relevant to the claims of animals—and I say this with all due deference to an impressive lineage of animal actors, from Rin Tin Tin the dog to Trigger the horse to Tommy the chimp. There will be more about Tommy later. Second, a person is “one of the three modes of being in the Trinitarian Godhead as understood by Christians” or, alternatively, “the unitary personality of Christ that unites the divine and human natures.” Again, with respect to the guiding question of this book, this conception of person seems neither here nor there. Third, a person is “a human being.” So, that’s it then: game over. A person must be one of these three things: a part in a play, an aspect of God, or a human. An animal is none of these three things. Therefore, no animal can be a person. I can stop writing now.

On the other hand, we philosophers are not supposed to slavishly adhere to dictionary diktat. If we did, we would all be out of a job. Think of all the philosophical problems that could be put to bed by teatime. I used to worry about things. For

Can Animals Be Persons?

example: What makes something mental? What sorts of things qualify as mental? A misspent youth, perhaps, but there was a time when questions such as this used to vex me. But, perhaps, I need only have consulted my Merriam-Webster. Something is mental, it tells me, if it is:

a. of or relating to the mind; specifically: of or relating to the total emotional and intellectual response of an individual to external reality

The first clause is, perhaps, not very helpful. But the second has substantial philosophical bite. Mental relates to “total emotional and intellectual response.” So, the emotions get in as well as the intellect. Descartes was wrong (and Aristotle was right): the mind is not a purely thinking thing. Even better—much better: “response to external reality.” So, there is an external reality! The existence of the mind proves it. Kant claimed it was the “scandal of philosophy” that no satisfactory proof of the external world had ever been devised. Too bad the MerriamWebster wasn’t around in 1781.1

b. of or relating to intellectual as contrasted with emotional activity.

Now, I have to admit, I am confused. Didn’t (a) claim that emotions were in?

c. of, relating to, or being intellectual as contrasted with overt physical activity.

Bugger! Overt physical is out. So much for 4E—embodied, embedded, enacted, and extended— cognition. That’s thirty years of my life down the toilet.

d. occurring or experienced in the mind: inner.

So, it has to be inner then. In your face, Wittgenstein!

I could go on, of course. In fact, I’d like to go on: I’m having an enormous amount of fun. (I particularly like condition (f) that proves dualism is true.) But I assume the absurdity of thinking we can settle philosophical disputes by appealing to the Merriam-Webster is evident to all. The question of whether animals are persons is

1 The Merriam-Webster, at this point, is very reminiscent of Sartre’s (1943/1957) “ontological proof” of non-mental reality, conducted in Section V of the Introduction to Being and Nothingness. Consciousness (mental reality) can exist only as directedness toward things it is not. The existence of consciousness is, therefore, sufficient to prove the existence of non-mental reality. Sartre characterized his position, reasonably enough, as a “radical reversal of idealism.” Is this an indication of the radical existentialist/ externalist leanings of the Merriam-Webster? Probably not: see definition (d).

Very Idea 3 not one that can be dismissed by simply looking in a dictionary and noting that person is defined as “a human being” or as something else animals are not.

Nevertheless, if we cannot dismiss the question simply by appealing to linguistic fiat, perhaps we might instead appeal to common sense? There is something deeply counterintuitive— something that runs profoundly against common sense— to the idea that animals can be persons. Or so I am frequently told. But, actually, I think this assertion of common- sense contrariness is simply false. Common sense is a lot more equivocal than one might think. In fact, common sense, aided by a little imagination, effortlessly distinguishes between the category of human being and that of the person. This is, to a considerable extent, because of a diet of top-quality science fiction films and TV series with which most of us have grown up. Spock is not human, but he is certainly a person. But he’s half human, you say. Okay then: Worf is not a human—he is entirely Klingon—but he is still a person. Switching Stars from Trek to Wars: Yoda is not human but is still a person. Jabba the Hutt is a person. Even the supremely annoying (and-insome- circles-rumored- Sith-lord) Jar Jar Binks is a person. But these figures, if not human, are all at least vaguely humanoid, one might reply. You can’t be a person unless you are vaguely humanoid. Okay, I shall up the ante a little: The Secret Life of Pets. If there were—presumably there are not, but if there were—dogs, cats, hamsters, birds, snakes, and so on that had mental lives as portrayed in this film, then we would be hard pushed to deny them the status of persons. The thing is: as far as their mental lives are concerned, they are just like us animated by the same thoughts, dreams, hopes, fears, and foibles as we. And if we are persons, how could they not also be persons? This idea— that whether or not something is a person is a matter of its mental life rather than its physical appearance—is as much a part of common sense as anything captured in the Merriam-Webster. We might think of these fictional cases as a kind of proof of concept: a demonstration of the possibility of persons who are not humans. Once we grant the possibility, the only question that remains is one of actuality. There might be nonhuman persons, but are there, actually, nonhuman persons? This book will argue that there are. There are, in all likelihood, plenty of them.

The thing about common sense is that it is eminently vulnerable to infection by the (no doubt) insalubrious activities of philosophers. These fictional cases, in fact, merely reinforce a distinction made by seventeenth- century English philosopher John Locke. Locke also distinguished the category of the human being from that of the person. The category of human being is a biological category: what makes an individual a human being is the possession of a certain genotype and therefore, typically, the possession also of a resulting phenotype (although Locke, preceding Gregor Mendel by nearly two hundred years, did not put the idea in

quite this way). The category of a person, on the other hand, Locke defined (a definition of which, I predict, you will be heartily sick by the end of this book) as: “a thinking intelligent being, that has reason and reflection, and can consider itself the same thinking thing, in different times and places, which it does only by that consciousness which is inseparable from thinking and seems to me to be essential, to it; it being impossible to perceive without perceiving that he does perceive.”2 The category of a human being is a biological one, but the category of a person is a psychological one that involves consciousness, thought, intelligence, reason, reflection, and the ability to “consider” oneself the same thinking thing in different times and places. Most humans are also persons in this sense: most, but not all. Some humans with serious and permanent brain damage, for example, would not qualify. And, as we know from Star Trek, Star Wars, and The Secret Life of Pets, not all persons need, necessarily, be humans (even if, as a matter of contingent fact, all actual persons are humans).

Locke’s definition is, as we shall see, far from perfect. I shall revisit it many times during the course of this book, clarifying it, refining it, extending it, and slowly making it more plausible. Refinements aside, the general neo-Lockean conception of the person as a psychological entity provides a guiding assumption of, and an organizing theme for, this book; and the arguments I develop will be developed in the context of this assumption. This will not please everyone. Opposed to Locke, there is a tradition of thinking of persons in bodily rather than psychological terms. According to what is known as animalism, for example, each one of us is not a psychological entity but a human animal, an organism of the species Homo sapiens. 3 I shall ignore non-psychological conceptions of the person for two reasons. First, animalism—the most influential recent version of the non-psychological conception of persons—is not an account of what persons are in general. It claims that we humans are animals, with the persistence conditions of animals. But animalism is perfectly compatible with the existence of nonhuman persons. If a nonhuman person were to exist, it would be an organism of its particular species—Pan troglodytes, Canis familiaris, or whatever. Animalists, in general, show no interest in such matters. Second, bodily conceptions of persons, such as animalism, seem to be far less hostile to the idea that animals are persons. Animals, after all, have bodies; and if it is the body rather than attendant psychology that is definitive of a person, there is no reason in principle why animals could not be persons. The primary opposition to the idea that animals are persons is going to derive from psychological conceptions of the person. This may seem odd, given that I employed

2 John Locke (1689/1979), Book 2, Chapter 27, p. 188.

3 See Eric Olson (1997) and Paul Snowdon (2014) for influential statements of this view.

Animals as Persons: The Very Idea 5 the psychological conception to ground a proof of concept: a demonstration of the possibility of persons who are not humans. But possibility is one thing, and actuality quite another. Locke’s psychological conception provides an exacting series of requirements that any animal would have to meet in order to qualify as a person. And, historically, the near universal consensus has been that no animal meets these requirements. While the (possible) dogs in The Secret Life of Pets may meet the psychological conditions required to be persons, most think that no real (i.e., actual) dog does. The strategy of this book is to assume the least convenient conception of a person available—to assume otherwise would smack of cheating—and then argue that animals still qualify as persons. The least convenient available conception of a person is the psychological one. I must admit a certain instinctive fondness for the neo-Lockean, psychological conception of persons. But, in this case at least, my neo-Lockean instincts dovetail nicely with dialectical necessity.4

2. Legal Persons

The claim that animals are persons—or, indeed, that anything is a person—is multiply ambiguous. In this section I begin whittling away at the ambiguities with a view to properly identifying the claim I am going to defend. The first source of ambiguity lies in the fact that the notion of a person can be understood in at least three ways: legal, moral, and metaphysical. The first task is to disambiguate these three senses of person.

An individual qualifies as a legal person if (and only if) his or her status as such is enshrined in law. Whether this is so is not, necessarily, an entirely principled matter. The law accords no overriding authority to logic or consistency. Rather, whether the law is willing, or unwilling, to recognize an individual as a person is partly, but essentially, dependent on the vicissitudes of social and legal history. As the American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. put it, in the opening stanza of his The Common Law:

The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public

4 This strategy contrasts with that of Elisa Aaltola (2008), whose goal is to identify which conception of person is most hospitable to the idea that animals can be persons. This she labels the “interactive” conception of personhood. There is, of course, nothing wrong with Aaltola’s project. Basically, her strategy is to argue that there is a way of thinking of persons on which some animals may qualify as such. But my approach is rather different. I shall try to show that even on highly unfavorable conceptions of personhood—rationalistic, individualistic, logocentric, please insert your preferred “ic”—animals can still qualify as persons. The type of philosophy pursued by this book will be what we might think of as philosophy in the worst-case scenario. I’ll talk more about this in the final chapter.

policy, avowed or unconscious, and even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have had a good deal more to do than syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation's development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics.5

All these factors— felt necessities, prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, prejudices— will go into determining who and/or what gets to be counted as a legal person. The results are quite striking. While the paradigm case of a legal person is still, perhaps, the normal (whatever that is) adult human being, you need to be neither human nor even alive to qualify as a legal person. It is not uncommon for US courts to extend personhood rights to non- sentient, non-living entities such as corporations, municipalities, and even ships.6 On the other hand, entities that are clearly both living and human have often had a harder time demonstrating their credentials for personhood. American legal history is replete with disputes over whether slaves, women, children, and Native Americans could be considered legal persons. The life of the law is, indeed, not logic.7

Having eventually— with, it has to be acknowledged, an unseemly amount of foot-dragging— come down in favor of slaves, women, children, and Native Americans, the legal debate has now moved on to animals. The reason these sorts of debates are possible, indeed inevitable, is that the law is never simply what is printed in black and white. Statutes always require interpretation, and their implications may go unrecognized. Consider, for example, the case of Tommy (briefly mentioned on page 1). Tommy is a chimpanzee—and quite a famous one at that: he starred alongside Matthew Broderick in the (1987) film Project X. In recent years, Tommy has been forced to live, isolated, in a small shed, in a used car lot in Gloversville, New York. In late 2013, the Nonhuman Rights Project filed for a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of Tommy. A writ of habeas corpus is an ancient legal device whose function is to ensure that all “legal persons” be protected from unjust imprisonment. If granted, therefore, the writ of habeas corpus would have established Tommy’s status as a legal person. In 2015, however, Justice Karen K. Peters of New York’s Third Department Appellate court ruled

5 Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1881), p. 1.

6 When Mitt Romney said, “Corporations are people, my friend,” he presumably intended this statement to be taken quite literally. The law, it seems, is on his side even if the 2012 electorate were not.

7 Compare Sir Edward Coke, “Reason Is the Life of the Law” (1628) p. 97b. It would appear not. I assume Holmes’s opening stanza was an allusion to this.

as Persons: The Very Idea 7 that chimpanzees cannot be legal persons because they “cannot bear any legal duties, submit to societal responsibilities, or be held legally accountable for their actions.” To an outsider at least, this ruling appears breathtaking in its naivety. To be a legal person is, fundamentally, to have certain rights— such as the right against unjustified imprisonment—under the law. The Peters ruling, in effect, limits legal personhood to what we might call legal agents—individuals that can bear legal duties, accept legal responsibilities, and be held legally accountable for what they do. This entails that large swathes of the human population are not legal persons—including children, the intellectually impaired, the senile, and so on. Individuals of these categories, on the Peters ruling, would not have the legal rights of persons.

There is a corresponding confusion one sometimes finds in the sphere of morality rather than legality. There is a certain meme to which some seem unusually susceptible—one often captured in the slogan “no rights without responsibilities.” This meme confuses moral agents and moral patients. A moral agent is an individual who understands that she has obligations and what those obligations are and can be held responsible if she fails to live up to them. A moral patient, on the other hand, is an individual who is deserving of moral consideration: an individual whom you should, morally speaking, take into account when you do something that might impinge on her welfare. The claim that a person cannot have rights unless she also has responsibilities is, in effect, the claim that a person cannot be a moral patient unless she is also a moral agent. On this view, we would have no moral obligations to children, the intellectually impaired, the senile, and so on. That’s a view. But, psychopaths aside, it is doubtful it has many adherents.

The “no rights without responsibilities” meme—one that seems to animate Peters’s ruling—is one that has insinuated itself quite widely into popular consciousness in recent decades. It does not, however, survive a moment’s serious scrutiny. Unfortunately, the effects of this untenable idea are still being felt. In two subsequent decisions, Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Barbara Jaffe ruled against habeas corpus petitions for other captive apes, Hercules, Leo, and Kiko, as well as a second habeas corpus petition for Tommy, largely on the grounds that she was bound by the Peters decision.

3. Moral Persons

The defining feature of a moral conception of the person is that it defines a person in moral terms. A straightforward—and rather undemanding— version

of this idea would simply define a moral person by analogy with the legal person. That is, on this undemanding conception, a moral person is simply an individual who is worthy of a certain kind of moral consideration or treatment. This simple conception seems unsatisfactory, for it fails to explain why an individual would be worthy of this sort of consideration. That an individual is worthy of moral consideration does not seem to be a brute fact about that individual but would, rather, be due to its possession of certain other qualities. A more demanding conception of the moral person would tie moral personhood to the possession of some specific morally relevant, or supposedly morally relevant, features of the person. For example, Tom Beauchamp characterizes a moral person as an individual who (1) is capable of making moral judgments about the rightness and wrongness of actions and (2) possesses motives that can be judged morally.8 To be a moral person requires having both moral motivations and the capacity for moral judgment.

One important implication of Beauchamp’s conception of moral personhood is that it drives a wedge between such personhood and what is known as moral considerability: the former is not a necessary condition of the latter. Something is morally considerable if it is worthy of moral consideration. But it is implausible to suppose that moral persons, in this sense, are the only things worthy of moral consideration. Young children, for example, are not moral persons in Beauchamp’s sense. But it would be strange—and disturbing— to conclude that children do not merit moral consideration: that, in effect, we have no moral obligations to them.9 Essentially, Beauchamp’s definition equates moral persons with moral agents, where a moral agent is something that acts for moral reasons and can be morally assessed—praised or blamed, broadly understood— for what it does. We can define moral persons in this way if we like, but we must then be careful not to think that only moral persons are moral patients, where the latter is defined as something that is worthy of moral consideration. Thus, Beauchamp’s view also drives a further wedge between the undemanding and the demanding conceptions of the moral person. The former equates moral personhood with moral considerability. The demanding conception, of the form endorsed by Beauchamp, equates moral personhood with moral agency. I shall address these issues no further since this moral sense of personhood is not the subject of this book.

8 Beauchamp (1999).

9 As we have seen, this, in effect, is the moral analogue of the mistake made by Justice Peters, when she tied legal personhood to the possession of social responsibilities. See Section 2.

4. Metaphysical Persons

Neither the legal nor the moral sense of personhood is the primary subject of this book. That accolade belongs to what I am going to call the metaphysical person. Michael Tooley observes: “It seems advisable to treat the term ‘person’ as a purely descriptive term, rather than as one whose definition involves moral concepts. For this appears to be the way the term ‘person’ is ordinarily construed.”10 This advice yields the metaphysical concept of the person. This choice of locution is, perhaps, ill advised: the term metaphysical may suggest some kind of arcane topic or inquiry, at odds with scientific investigation. Quite the contrary: I use the term metaphysical in its standard philosophical use, meaning, roughly, “pertaining to what something is.” Beauchamp, from whom I have co-opted the expression metaphysical person, captures the general idea very nicely: “As I draw the distinction, metaphysical personhood is comprised entirely of a set of person-distinguishing psychological properties such as intentionality, self- consciousness, free will, language acquisition, pain reception, and emotion. The metaphysical goal is to identify a set of psychological properties possessed by all and only persons.”11 Beauchamp assumes the properties in question will be psychological, and this is a common assumption (although not mandatory). Which psychological properties they may be—and whether only psychological properties are relevant—is, of course, open to dispute. But, at present, I am concerned only with the general idea of the metaphysical person. An individual qualifies as a metaphysical person if and only if he or she (or it) possesses certain non-moral, non-legal features that confer the status of persons upon them. Crucially, the individual in question will possess these features independently of whether he is accorded the status of a person in law and/or regarded as having a certain, distinctive moral status.12

In claiming that my focus will be on the metaphysical sense of the person rather than its moral and legal counterparts, I do not wish to give the impression that there are no interesting connections between the three. The three conceptions are distinct but not unrelated. If we were all to agree that some nonhuman individual— Tommy the chimp, for example—is a person in the metaphysical sense, this would (or could) have important moral implications, implications concerning the kind

10 Tooley (1983), p. 51.

11 Beauchamp (1999), p. 309.

12 Of course, whether an individual is a moral or legal person also depends on the possession of certain non-moral, non-legal features. But in this case, such features confer the status of moral or legal person on the individual only in conjunction with moral principles or legal statutes and legal interpretation of those statutes. There is no echo of this reliance in the case of the metaphysical person. My thanks to David DeGrazia for allowing me to clarify this point.

of consideration or treatment he is owed. And, within the constraints identified by Holmes, it may also have important legal ramifications. If widely accepted, the metaphysical status of animals as persons may also, eventually, impact on the legal status of animal as persons, this acceptance becoming, as Holmes puts it, among “the felt necessities, intuitions (avowed or unconscious) or prejudices” that shape our legal conception of animals. The metaphysical status of animals as persons may, therefore, certainly have moral and legal implications. But these implications will be corollaries of the fact that animals are persons, rather than constitutive of what it is for an animal to be a person. The primary focus of this book is the metaphysical conception of the person. I shall argue that at least some—in all likelihood, many—animals are persons in the metaphysical sense.

5. Conditions of (Metaphysical) Personhood

The focus may have narrowed to the metaphysical person, rather than its moral and legal counterparts. But there is still much tidying up to do. The category of the metaphysical person is as mottled and messy as one could imagine. There are a variety of ingredients that might go into making an individual a person in the metaphysical sense, and the relative importance of each is, to say the least, not immediately clear. I shall begin with a survey of the literature—but as much of this “literature” is also a survey of the literature, it might be better to think of what I am doing as a meta- survey of the literature.

Daniel Dennett has identified six distinct “themes,” each of which has, by someone at some time, been advanced as a necessary, sufficient, or necessary and sufficient condition of personhood: a person is (1) a rational being, (2) a being to which states of consciousness are attributed or to which psychological or intentional predicates are ascribed, (3) a being to which a certain sort of attitude or stance is adopted, (4) a being capable of reciprocating— treating other persons as persons, (5) a being capable of verbal communication, (6) a being that is conscious in some special way— typically, self- conscious.13

Thomas White, in developing his case for the personhood of dolphins, lists the following as ingredients or elements of persons. This is a list White has culled from the philosophical literature—including Dennett’s contribution—and he does not necessarily endorse it but, rather, regards it as useful for getting a sense of the sorts of features many people have in mind when they think of persons. An individual is a person if it has the properties of (1) being alive, (2) being aware, (3) feeling

13 Dennett (1987a).

Animals as Persons: The Very Idea 11 positive and negative sensations, (4) having emotions, (5) having a sense of self, (6) being able to control its own behavior, (7) being able to recognize other persons and treat them as such, and (8) having a variety of sophisticated cognitive abilities, such as analytical thinking, learning, or complex problem- solving.14

Tom Beauchamp identifies the following list of features that have been thought to confer personhood on an individual. He writes: “Cognitive conditions of metaphysical personhood similar to the following have been promoted by several classical and contemporary writers: (1) self-consciousness (of oneself as existing over time); (2) capacity to act on reasons; (3) capacity to communicate with others by command of a language; (4) capacity to act freely; and (5) rationality.”15

The lists of Dennett, White, and Beauchamp are themselves compiled on the basis of literature review. Historically, the rationality theme is associated with Kant,16 Aristotle,17 and more recently Rawls.18 Peter Strawson defends the conception of persons as subjects of psychological attribution.19 The idea of personhood being a matter of adoption of a stance is associated with Sellars,20 Putnam,21 and Dennett,22 among others. The reciprocity condition is one that has been emphasized by Rawls23 and Strawson,24 among others. The self- consciousness theme is associated with Sartre,25 Locke,26 and Frankfurt,27 among many others. Some writers will accentuate one feature over all others. For example, Michael Tooley writes: “What properties must something have in order to be a person, i.e., to have a serious right to life? The claim I wish to defend is this: an organism possesses a serious right to life only if it possesses the concept of a self as a continuing subject of experiences and other mental states, and believes that it is itself a continuing entity.”28 Others are more inclusive, willing to allow that several features can be important in the making of a person. As we have seen, Locke tells us that a person is “a thinking intelligent being, that has reason and reflection, and

14 White (2007), p. 156.

15 Beauchamp (1999), p. 310.

16 Kant (1781/87).

17 Aristotle (1999), 1. 13.

18 Rawls (1971).

19 Strawson (1959), pp. 101–102.

20 Sellars (1966).

21 Putnam (1964).

22 Dennett (1971).

23 Rawls (1971).

24 Strawson (1962).

25 Sartre (1943/1957).

26 Locke (1689/1979).

27 Frankfurt (1971).

28 Tooley (1972), p. 39.