List of Figures and Table

Figures

I.1. Lieutenant Ernest Brooks, ‘British troops in a sunken road between La Boisselle and Contalmaison, July 1916’. © Imperial War Museum, Q 813. xi

I.2. Ariel Varges, ‘Naval rating from British Light Cruiser Lowestoft with men of the 7th Battalion South Wales Borderers having refreshments at a cafe in Salonika, April 1916’. © Imperial War Museum, Q 31921. xii

1.1. ‘Troops of the 1st Battalion, 4th Gurkha Rifles (1st/4th GR) during physical training exercise on the upper deck of SS El Kahira (Khedival Mail) which brought the Battalion from Mudros to Alexandria, 1915’. © Imperial War Museum, Q 81655. 64

2.1. W. J. Brunell, ‘A British soldier admiring a view in old Constantinople, with a row of wooden houses in the foreground’. © Imperial War Museum, Q 14192. 99

3.1. Ariel Varges, ‘British troops [sic] constructing a broad gauge railway through Salonika, January, 1917’. © Imperial War Museum, Q 32690. 135

4.1. W. J. Brunell, ‘Two men of the 9th Battalion, South Lancashire Regiment, share a hookah outside a cafe at Chanak’. © Imperial War Museum, Q 14298. 189

5.1. W. J. Brunell, ‘Royal Navy ratings at the signal station on the top of Galata Tower, showing the view across the Golden Horn and wide area of Constantinople’. © Imperial War Museum, Q 14273. 236

Table

I.1. Population by religious denomination for Constantinople (1914), Alexandria (1917), and Salonica (1913). 30

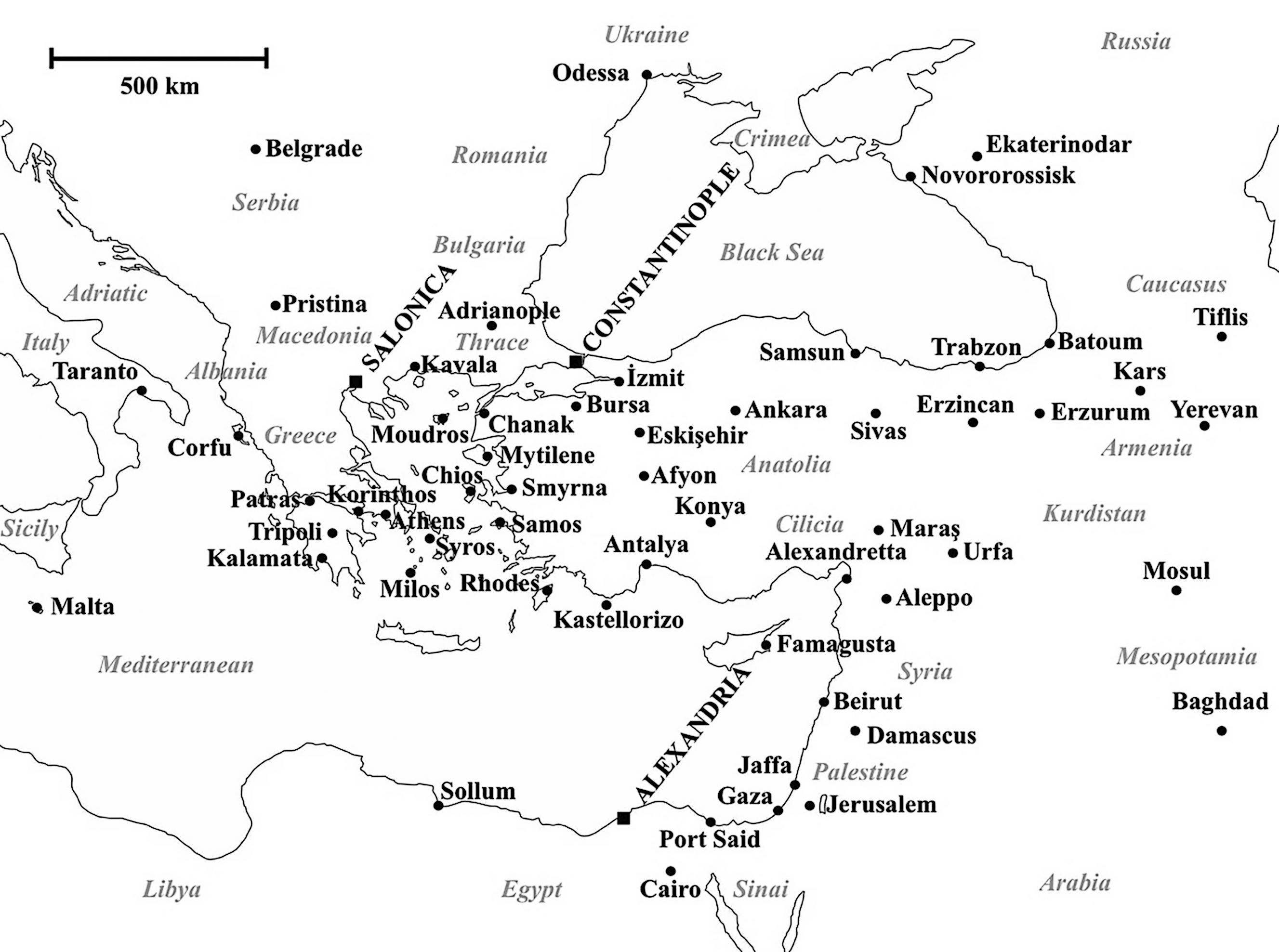

Map 1. Map of Eastern Mediterranean towns mentioned in the Book. Modified from original at https://d-maps.com/m/mediterranean/meditmax/meditmax01.gif.

Figure I.1 Lieutenant Ernest Brooks, ‘British troops in a sunken road between La Boisselle and Contalmaison, July 1916’. © Imperial War Museum, Q 813.

Figure I.2 Ariel Varges, ‘Naval rating from British Light Cruiser Lowestoft with men of the 7th Battalion South Wales Borderers having refreshments at a cafe in Salonika, April 1916’. © Imperial War Museum, Q 31921.

Introduction

The First World War in the popular imagination centres on the trenches of the western front. While capturing one of the most distinct features of the war, images such as Figure I.1, showing groups of men in the mud-churned fields of northwestern Europe, exclude the diverse actors and scenes that composed the full panoply of the conflict. Turning to the cities of the eastern Mediterranean, a very different image of the war is frequently encountered, as illustrated by Figure I.2. Soldiers and sailors sit at cafe tables and walk paved streets shared with combatants from different Allied nations and colonies and civilians at leisure and at work. They are distinguished by headwear whose classification had long fascinated travellers to and rulers of Ottoman towns such as Salonica, captured here, but also Alexandria and Constantinople, the triad of cities whose occupation by British forces is the focus of this book.1 The profusion of naval caps, slouch hats, and forage caps worn by British military personnel and their allies between 1914 and 1923 was symbolic of a new order that bound these cities together, a transitory interlude between the Fez of the Tanzimat era and its replacement by western styles later adopted in Greece, Turkey, and Egypt. As the journalist and writer Salahaddin Enis noted on his return to occupied Constantinople from the Ottoman eastern front, ‘the difference was that the number of hats had increased, the quantity of flags had multiplied’.2

The scene depicted by this and many similar photographs was made possible by the mass movement of people and materials across the Mediterranean in the service of the Entente’s fight against the Ottoman Empire and the other Central Powers. This book is foremost concerned with the British military personnel among them, who reached the eastern Mediterranean in unprecedented numbers and whose testimony is recorded in numerous letters, diaries, and memoirs. Their lives and the regimes established to govern them on board transport ships, in military camps, and above all in the cities they occupied formed the basis of a new empire which radiated out from places where soldiers were concentrated and imposed itself on residents of these localities and beyond. Though instigated by the war, this imperial project did not come to an end with the signing of the 1918

1 As this book deals primarily with British thoughts and actions in these cities, I have used the dominant Anglophone place names from the period (Constantinople for Istanbul; Salonica for Thessaloniki; Alexandria for al-ʾIskandariyya; Smyrna for İzmir; Batoum for Batumi). For less wellknown sites, modern Turkish and transliterated Greek and Arabic names are used for ease of location.

2 Salahaddin Enis, Sara ve Cehennem Yolcuları (Istanbul: Kesit Yayınları, 2016), p. 39.

Britain’s Levantine Empire, 1914–1923. Daniel-Joseph MacArthur-Seal, Oxford University Press (2021).

© Daniel-Joseph MacArthur-Seal. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192895769.003.0001

armistices with Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire, Austria-Hungary, or Germany. The British military continued to expand its reach, adding Batoum and Constantinople to the cities of Salonica, garrisoned since 1915, and Alexandria, occupied since 1882. These disparate sites, and a number of islands scattered between them, were connected by networks of military logistics and conflated by the men who passed between them into a single demographic and geographic constituency known by the name, among others, of the Levant. This book aims to establish the significance of this neglected constellation of military power, which I term Britain’s Levantine empire.

A Levantine Empire

The term ‘Levant’ is suitably ambiguous for this ill-defined empire. Although the word is often found in historical sources and occasionally deployed by historians, its definition and the discourse in which it was embedded have rarely received academic attention. As an area of contemporary research, its remit has been largely restricted to the territories now comprised by Palestine, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, as an English and French synonym for the Arabic Al Sham. 3 However, its earlier popularity reflected multiple and more expansive meanings. The Levant not only referred to a broader ranging geographic region, often including Salonica, Constantinople, and Alexandria, but described demographic, social, and cultural features. Evelyn Baring, in his history and description of Egypt, where he served as consul general from 1883 to 1907, noted that ‘the Levantines, though not a separate nation, possess characteristics of their own which may almost be termed national’.4 The Levant was in effect an ethnographic, as well as a geographic, category.

In recent years, academics have begun to explore these forgotten connotations. A 1998 conference in Izmir, of which a selection of papers were published in the 2006 volume European or Levantine? marks the earliest critical reflection on the term by historians.5 Since 2011, editors and authors in the Journal of Levantine Studies have engaged with the etymology and ambiguity of the term in its historical and current use.6 Family histories conducted by self-identified Levantines, whose association, Levantine Heritage, maintains a valuable website and organizes conferences for scholars within and outside of the academy, have helped bring cultural uses of the term to light.7 Philip Mansel’s recent book Levant:

3 The Council for British Research in the Levant, for example, supports research into these countries, ‘About Us’, accessed 15 November 2019, https://cbrl.ac.uk/about-us.

4 Evelyn Baring, Modern Egypt (London: Macmillan, 1908), p. 246.

5 Arus Yumul and Fahri Dikkaya, eds, Avrupalı mı Levanten mi (Istanbul: Bağlam Yayıncılık, 2006).

6 ‘About Us’, accessed 20 February 2015, http://www.levantine-journal.org/AboutJLS.aspx.

7 ‘Levantine Heritage’, accessed 21 June 2017, http://levantineheritage.com/.

Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean, and its inevitable discussion of the term, however, seems overly normative in its definition of the Levantine as an ideologically flexible, pluralist, commercially driven, libertarian mentality that ‘put deals before ideals’.8 Indeed, the association of these traits with the Levant in part derives from the more pejorative language of British officers and officials studied here, for whom the Levantine ‘implied the elevation to a principle of mere financial success; a blurring of essential standards; a certain moral suppleness, and probably the wrong attitude during shipwreck’.9 Rather than attempt to conduct a retrospective ethnography of the ill-defined Levantine population, this book is concerned with British discourse on the Levant and its correlation with imperial expansion in the region.

Although its etymological origins, derived from the French verb ‘lever’, suggest, like the Arabic mashriq and Turkish şark, the direction of the rising sun and seem to make it thereby no more specific than the ‘Orient’, the Levant came to refer only to the most ‘western’ part of the ‘east’. The years under study saw shifting English namings for the lands bounding the eastern Mediterranean, each tied to various political projects. Naval War College lecturer Thayer Mahan coined the soon to be dominant term ‘the Middle East’ in 1902, while another American academic, James Henry Breasted, first wrote of ‘the Fertile Crescent’ in 1916, his ancient history of the region hinting at the prosperity to which it could be restored under western guidance.10 It was towards the end of the war that use of ‘Middle East’ flourished, displacing the popular nineteenth-century appellations ‘Asiatic Turkey’ and ‘Turkish Arabia’, a neat corollary to the British aim of dividing Ottoman Turkey from its Arab provinces.11 New names reflected the instability of regional politics, a point recognized by diplomatic officials in the area like Laurence Grafftey-Smith who begins his memoirs of service in what he defiantly persists in calling the ‘Levant’ with a discussion of place names that changed with the ‘perpetual kaleidoscope of Time’.12

This linguistic division of the Arab majority provinces from Anatolia came soon after the Balkan Wars delivered the coup de grace to the decreasingly popular term ‘European Turkey’.13 This tripartite division of the eastern Mediterranean rim left British servicemen travelling across these divides with the dialogic problem of how to group parallel phenomena observed on its Greek, Ottoman, and

8 Philip Mansel, Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean (London: John Murray, 2010), p. 3.

9 Laurence Grafftey-Smith, Bright Levant (London: John Murray, 1970), p. 34.

10 Thomas Scheffler, ‘“Fertile Crescent”, “Orient”, “Middle East”: The Changing Mental Maps of Southwest Asia’, European Review of History: Revue Européenne d’Histoire, 10 (2003): pp. 253–72, at p. 255.

11 James Renton, ‘Changing Languages of Empire and the Orient: Britain and the Invention of the Middle East, 1917–1918’, The Historical Journal, 50 (2007): pp. 645–67, at p. 646–7.

12 Grafftey-Smith, Bright Levant, p. 1.

13 Maria Todorova, Imagining the Balkans (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 28–30.

Egyptian shores. Common features, at times accentuated or effected by Britain’s trans-Mediterranean military presence, straddled national borders, continental divisions between Europe, Asia, and Africa, linguistic boundaries between Arabic-, Turkish-, and Greek-speaking lands, and the proclaimed geographic units of the Balkans, Anatolia, and North Africa. All could find a home in the multifarious term ‘Levant’.

Despite the erection of political and terminological borders between them, the cities of the eastern Mediterranean continued to be bound together by trade, migrations, and common customs. The word Levant is perhaps most frequently encountered in the names of the companies implicated in the maritime commerce taken to be such a defining character of the region. Liners advertised sailings from major European and American cities to the Levant in order to suggest that they would stop at multiple ports in the region. Post-war attempts to establish a Smyrna service by the Deutsche Levant Linie were blocked by Allied insistence on the armistice’s prohibition of German ships’ entry into Ottoman ports.14

The British-backed Levant Stevedoring Company Limited’s fees became the subject of commercial complaints in the crowded quays of post-war Constantinople.15

During the war, as the international companies operating in the Ottoman Empire suffered blockade and isolation, Allied military units arriving in the eastern Mediterranean took up the title. The British Levant Base in Alexandria was the logistical centre of the Salonica campaign, one part of the much mocked ‘trinity’ of the ‘Mediterranean faith’, as soldiers satirized it, alongside the Army of Egypt and the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.16 From occupied Constantinople, French intelligence attached to the Armée du Levant operated under the title of the Bureau du Levant, producing Arabic propaganda for consumption in Syria.17 The Italian military also opted for the name Division del Levante, with only the British Army of the Black Sea, the new name given to the Army of the Orient on its leaving Salonica for Constantinople, omitting the title.

There was such enthusiasm for British commercial prospects on the back of its military expansion in the eastern Mediterranean that a new Levant Company was founded in 1918, ‘perpetuating the spirit of patriotism and enterprise’ that characterized the two-hundred-year history of the original Levant Company whose charter had ended in 1825.18 British success in the Levant trade, to which still surviving merchant families such as the Whittalls bore testament, provided the

14 National Archives (NA), Records of the Foreign Office (FO) 371/5164, ‘Conférence des Hautes Commissionnaires’, 5 November 1920.

15 NA, FO 371/5131, F. Heald and Rizzo, Steam Ship and Commission Agents, to British Captain of the Port, Galata, 18 May 1920, f. 229.

16 Middle East Centre Archives (MECA), Loder GB165-0184, ‘After Morning Parade’.

17 NA, FO 141/480/19, ‘Activities of the French Bureau du Levant in Constantinople’, 12 August 1921.

18 Maurice de Bunsen, ‘The New Levant Company’, Journal of The Royal Central Asian Society, 7 (1920): pp. 19–31, at p. 26.

country’s representatives with a collective history, identity, and mission in the region.19 Within two years of its establishment, the Levant Company’s modern successor boasted branches in Athens, Alexandria, Beirut, Jaffa, Batoum, Constantinople, Salonica, Baghdad, Odessa, and Novororossisk. Academic interest in the original Levant Company, seen in the books of A. C. Wood and Gwilym Ambrose, was revived in the interwar period, when the economic exploitation of the new mandate states of Transjordan, Syria, and Iraq aroused further commercial excitement.20 The polymorphous connotations of the term Levant, tied to the region but not associated with the names of existing political units whose future was so uncertain, explain its recrudescent popularity.

In spite of such interest, there was no consensus on the borders of the Levant or even whether it formed one contiguous space. Instead, the Levant, like the ‘Orient’ described by Edward Said, remained above all an imagined geography, one mentally rather than territorially mapped.21 For British soldiers and their superiors this Levantine world was conceived as coextensive with the highpoint of Allied military expansion in 1919. This was no coincidence, for the content of this imagined Levantine geography served as the legitimating underpinning for British control in the eastern Mediterranean. In its instrumentality to British political ambitions, the conception of the Levant paralleled that of Arabia, as formulated by scholars and soldiers in the concurrent project of establishing British domination in the Middle East.22 But while Arabia was expansive, distant, and penetrated only by the odd intelligence officer, overflown by British pilots, or dissected from afar by orientalist geographers, the Levant was characterized by its permeability to the wider world and the confluence of people and goods. Thus, it was the port cities Alexandria, Constantinople, and Salonica, through which British military material and human resources coursed, that formed the conceptual keystones of the Levantine imaginary and are the focus of this study.

The name Levant semantically sequestered these city-nodes from their hinterlands, moving into which British power dissipated. Classical references to Alexandria ‘ad Aegyptum’ (at, rather than in, Egypt) were repeated by members of Britain’s occupying forces like the army chaplain E. C. Mortimer who noted that ‘Alexandria of course is a town of the Levant, rather than a town of Egypt’.23 Likewise, Constantinople, and more specifically the central district of Pera, was cited as ‘la ville du Levant’, or ‘the capital of Levantinia’, at the moment that British

19 Christine Laidlaw, The British in the Levant: Trade and Perceptions of the Ottoman Empire in the Eighteenth Century (London: I. B. Tauris, 2010), p. 223.

20 Alfred C. Wood, A History of the Levant Company (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1935); Gwilym P. Ambrose, ‘English Traders at Aleppo (1658–1756)’, The Economic History Review, 3 (1932): pp. 246–67.

21 Edward Said, Orientalism (London: Penguin, 1977), p. 55.

22 Priya Satia, Spies in Arabia: The Great War and the Cultural Foundations of Britain’s Covert Empire in the Middle East (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 13–14.

23 Imperial War Museum (IWM), Private Papers of E. C. Mortimer, ‘Memoirs of E. C. Mortimer’, p. 7.

diplomats were rebuffing Turkish petitions to retain the city under the terms of the forthcoming Treaty of Sèvres.24 Indeed, the term Levantine was rarely applied to those living beyond Alexandria, Constantinople, Salonica, Port Said, Beirut, Smyrna, and a smattering of smaller coastal towns and islands. The population of their hinterlands was assumed to take a more ethnically and culturally homogenous character, providing a potential basis for the redemption of the Ottoman Empire’s supposed ethno-territorial component parts on national lines. On 18 December 1918, barely a month after British forces had reached Constantinople, Leader of the House of Lords and later Foreign Secretary George Curzon informed the war cabinet’s Eastern Committee that ‘those who know the Turk in his own highlands in Asia Minor and elsewhere always speak of him with respect as a simple-minded worthy fellow who dislikes as much as anybody else the system of corruption and intrigue that goes on at Head Quarters’, followed by arguments that the Ottoman government should be deprived of its capital and removed to an inland city such as Bursa.25 Likewise, the vigorous, ‘manly, frugal and hardy’ Arab was cultivated by ‘the spirit of the desert’, an environment defined by its proximity to god and nature and distance from the corrupting influences of urban society.26 These at times romanticized rural settings could hardly be further from the large cities of Salonica, Alexandria, or Constantinople, defined by their decadence and openness to external influences rather than purity or isolation.

British confusion at social, religious, and ethnic distinctions and observance of physical, behavioural, and cultural commonalities between the inhabitants of these cities seemed to necessitate some collective identification. Thus, the abstract land of the Levant was populated by the equally uncategorizable Levantine. When applied to the population by historians, the term Levantine has largely been taken to be an unproblematic, if vague and anachronistic, way of referring to longresident western European populations in and around the Ottoman Empire, yet the term was equally malleable and invested with as many meanings as its geographic corollary.27 At times it denoted only the multi-generational Catholic population, at others it included culturally ‘westernized’ Jewish, Orthodox, and Muslim residents. The ambiguity of its definition prevented its systematic use in official census data,28 although the Association Catholique pour la Protection de la Jeune Fille had no problem including it as a category, shared with ‘indigenes’, in

24 Bertrand Bareilles, Constantinople, Ses Cités Franques et Levantines (Péra, Galata, Banlieue) (Paris: Bossard, 1918), p. 45; Harold Armstrong, Turkey in Travail: The Birth of a New Nation (London: John Lane, 1925), p. 79.

25 British Library (BL), IO/L/PS/10/623, War Cabinet Eastern Committee, 23 December 1918.

26 William Muir, The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline and Fall, from Original Sources (London: Religious Tract Society, 1892), p. 596.

27 Mark Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims, and Jews, 1430–1950 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), pp. 147, 164, 218.

28 In the 1917 Egyptian census, those who might be thought of as Levantines were categorized as ‘foreigner’, ‘other [as opposed to Muslim] local subjects’, or according to religious denomination. See The Census of Egypt Taken in 1917 (Cairo: Government Press, 1920), pp. 20–1; 460–1.

tabulations of the ‘nationalités’ of the young women it annually claimed to have rescued from prostitution.29

The ambiguity of this Levantine population provoked racial anxieties centred on miscegenation and assimilation. Nineteenth-century ethnographic theory had raised fears of racial decomposition and the dissolution of the racial order that underpinned British imperial dominance.30 The Levantine was a designation that straddled different races, religions, and nationalities and its amorphous form threatened to incorporate even the British soldier or civilian, let alone members of more susceptible nations bordering the Mediterranean. Harold Armstrong, a staff officer in Constantinople, ‘realized’ that whenever the ‘hardy honest and steady’ Anatolian Turk was ‘taken and educated’ in Constantinople ‘he instinctively absorbed that which was superficial and he became a levantine’, a people who were ‘the evil results of the mating of the East and the West’.31

These fears were shared by Ottoman officials and public opinion-makers, for whom the word ‘Levanten’, defined as ‘Those who display themselves in European style though being from the Eastern people, Christian imitators of the Franks, sweet water Franks’,32 gained popularity in the early twentieth century. A longrunning literary and press discourse critical of the western affectations of members of the Muslim urban bourgeoisie identified the Levantines as key intermediaries in the partial introduction of European thoughts and fashions.33 Ziya Gökalp, the principle ideologue of Turkish nationalism, criticized Ottoman elites whose ‘understanding of European civilization did not go beyond that of the Levantines of Pera’ and accordingly ‘simply imitated the superficial lustre, the luxury, the ornateness, and such other rubbish of Europe’.34 Conservative journals urged the utmost vigilance against the ‘sordid manoeuvres’ of these ‘nationless Levantines’ lest Muslim youth be corrupted by their ‘sorcery and charms’.35 The rise of ethnic nationalism and the increasingly outspoken hostility to the position of non-Muslims, and in particular the ‘comprador’ bourgeoisie that included many notable Catholic and Protestant families, in the political economy of the late Ottoman Empire and early Turkish Republic further marked out the Levantine population and their ‘confused lineage’ as a target.36

29 Centre des Archives Diplomatiques de Nantes (CADN) 20PO/1/22, Association Catholique Pour la Protection de la Jeune Fille, ‘Deuxième Rapport’ (Alexandria, 1915), p. 7.

30 Robert Young, Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture, and Race (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 18–19.

31 Armstrong, Turkey in Travail, p. 78.

32 Raif Necdet Kestelli, Resimli Türkçe Kamus (Istanbul: Ahmet Kâmil Matbaası, 1928), p. 667.

33 Köksal Alver, ‘Züppelik Anlatısı ve Toplum: Türk Romanında Züppe Tipi’, Selçuk Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 16 (2006): pp. 163–82, at p. 180.

34 Ziya Gökalp, ‘The Programme of Turkism’, in Turkish Nationalism and Western Civilization: Selected Essays of Ziya Gökalp (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959), p. 287.

35 Rumeli, ‘Gençlerde Milliyet Hissi Ölüyor! Levantinizim’, Sebillürreşad, 2 May 1912.

36 Türk Ansiklopedisi, vol. 23 (Ankara: Millî Eğitim Basımevi, 1976), pp. 12–13, quoted in Edhem Eldem, ‘“Levanten” Kelimesi Üzerine’, in Yumul and Dikkaya, eds, Avrupalı mı Levanten mi, p. 17.

British observers shared the conviction that the Levantine population were not true Europeans, whatever passport they happened to carry. Baring had warned readers of making assumptions on the basis of nationality when ‘the Frenchman resident in Egypt is only technically a Frenchman’ or ‘the Italian may in reality be only half an Italian in so far as his national characteristics are concerned’.37 Even European-born residents in the Levant were at risk of losing their national character. French General Albert Defrance’s long service in Macedonia and Constantinople had caused him to become ‘partially Levantinised’, according to one British officer.38 While some expressed a comic confidence in how ‘The Britisher in the Levant insists on remaining a Britisher though the heavens fall’, who would tell ‘the climate and customs of the country to go to the devil and breakfasts on bacon and eggs’, the prospect of acculturation and assimilation remained a widespread concern.39 Baring’s faith that ‘Germans’ and ‘Englishmen’ ‘rarely become typical Levantines’, was doubted by some of his successors and by German authorities in the same period, who feared their co-nationals in the eastern Mediterranean would be ‘Levantinized’.40 Consular officials and other ‘upstanding’ foreign nationals found the category of Levantine to be a useful tool to police the boundaries and maintain the prestige of the designation ‘European’, a concern of imperial authorities across Asia and Africa.41

In rare instances, this Levantinization was welcomed as a marker of adaptability to new surroundings, though not without reservation. Loder wrote home how ‘I am getting to be quite a passable Levantine now For me there is something very attractive about it all, though taken as a whole I don’t suppose a more scallywag collection of human beings ever was gathered together before’.42 Soonto-be-famed writer E. M. Forster too seemed pleased to adjust himself to what he called ‘the slow Levantine degringolade’ during his work as an ambulance driver in Alexandria, a city that symbolized ‘a mixture, a bastardy, an idea which I find congenial and opposed to that sterile idea of 100% in something or other which has impressed the modern world and forms the backbone of its blustering nationalisms’.43 Forster’s romanticization of the Levantine is echoed by numerous modern writers looking back on turn-of-the century Alexandria and its sister-cities across the Mediterranean, often lapsing into a nostalgia that has distorted research

37 Baring, Modern Egypt, vol. 2, p. 246.

38 MECA, Loder GB165-0184, Loder to Father, 23 December 1917.

39 ‘The Athens Exhibition’, Orient News, 4 November 1919, p. 1.

40 Baring, Modern Egypt, vol. 2, p. 248; Malte Fuhrmann, ‘Cosmopolitan Imperialists and the Ottoman Port Cities: Conflicting Logics in the Urban Social Fabric’, Cahiers de la Méditerranée, 67 (2003): pp. 149–63, at p. 154.

41 Julia Clancy-Smith, ‘Marginality and Migration: Europe’s Social Outcasts in Pre-Colonial Tunisia, 1880–1881’, in Eugene Rogan, ed., Outside In: On the Margins of the Modern Middle East (London: I. B. Tauris, 2002), p. 154.

42 MECA, Loder GB165-0184, Loder to Mother, 1 July 1917.

43 King’s College Archive (KCA), E. M. Forster Papers, E. M. Forster, ‘The Lost Guide’, ff. 99–101.

agendas in the region’s urban history,44 and it is important to note that his was a lonely voice among British visitors.

For most, the Levantine represented social and racial disorder in a setting of urban degradation. Her experience of Pera made the journalist Grace Ellison realize ‘the danger of losing oneself in the ambition to be truly cosmopolitan’, and signalled a ‘terrible warning’ that ‘people belonging to all nations . . . have the soul of none’.45 Personal encounters with the uncategorizable masses of the Levantine city seemed to confirm the ‘pessimistic and fearful understandings of modernity’ that permeated the ethnographic and eugenic sciences popular in the period, particularly when dealing with the Orient.46 This pessimism distinguished British projections for the future of the eastern Mediterranean from the utopian visions encapsulated by the Greek Megali idea of the unification of the Hellenic world, Turanist aspirations for a Turkic empire linking Constantinople and Central Asia, Muslim scholars’ hopes for a renewed pan-Islamic caliphate, or Bolshevik predictions of world revolution.47 Early optimism that British intervention could reshape the region on a ‘stable and friendly basis’, without prejudice to its existing privileges, relations with its allies, and good standing in Muslim, Jewish, and eastern Christian opinion, quickly evaporated, to be replaced by a pervading sense of crisis and potential catastrophe as Britain’s Levantine empire struggled to contain these rival political projects.48

Interpreting Britain’s Rise

Histories of British expansion in the eastern Mediterranean have regarded the strategic imperatives of empire as the key drivers of policy. Debates on British encroachment on the Ottoman Empire in imperial history have largely been conducted with this broad assumption, with academic disputes centring around which interest or set of interests were most significant, be it strategic communications,

44 Will Hanley, ‘Grieving Cosmopolitanism in Middle East Studies’, History Compass, 6 (2008): pp. 1346–67, at p. 1346.

45 Grace Ellison, An English Woman at Angora (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1923), p. 294.

46 Susan Bayly, ‘Racial Readings of Empire: Britain, France, and Colonial Modernity in the Mediterranean and Asia’, in Leila Fawaz and Christopher A. Bayly, eds, Modernity and Culture: From the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), p. 285.

47 Anastasia Stouraiti and Alexander Kazamias, ‘The Imaginary Topographies of the Megali Idea: National Territory as Utopia’, in Nikiforos P. Diamandouros, Thaleia Dragōna, and Çağlar Keyder, eds, Spatial Conceptions of the Nation: Modernizing Geographies in Greece and Turkey (London: I. B. Tauris, 2010), pp. 12–28; Cemil Aydin, The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia: Visions of World Order in PanIslamic and Pan-Asian Thought (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), pp. 99–111; Şuhnaz Yılmaz, ‘An Ottoman Warrior Abroad: Enver Paşa as an Expatriate’, Middle Eastern Studies, 35 (1999): pp. 40–69.

48 NA, Records of the Cabinet Office (CAB) 24/72/6, ‘Memorandum on the Settlement of Turkey and the Arabian Peninsula’, p. 10.

trade, resources, or great power rivalry.49 A broad range of political sympathies have been accommodated within this approach, with apologists for Britain’s role emphasizing the harmony of British self-interest with local economic and political development, while critics have followed the suit of contemporary anti-imperialists in emphasizing the harm done by economic exploitation and accompanying political repression.50

This framework of understanding originated with the earliest memoirs of those who had accompanied British forces or had been engaged in implementing policy in the region, with Baring’s defence of the British decision to occupy Egypt and long-term British resident W. S. Blunt’s excoriation of the policy setting the tone for future sides in the debate.51 First World War campaigns in the eastern Mediterranean were well-represented among the large number of memoirhistories published from the 1920s onwards.52 Those writing on personal experiences in the Salonica campaign, such as the soldiers Harold Lake and Arthur Griffin Tapp and the nurse Jane Dare, were keen to stress the campaign’s impact on the course of the war and their and their compatriots’ hardships, in order to counter criticisms of the Salonica front as a strategic diversion and an easy posting.53 Soldiers serving in Egypt, such as Hector William Dinning and M. S. Briggs, attracted readers with their combination of war memoir and exotic travel guide.54 Most saw little need to criticize the course and conduct of the war itself, though lower level incompetence was a frequent target.

Britain’s post-war presence in Turkey, a policy publicly acknowledged to have failed and therefore devoid of the obstacles to critique presented by 1914–18 and the weight of the British war dead, was more readily criticized by memoirists and political commentators. Dissension in the British coalition government over the extent of Prime Minister Lloyd George’s secret support of Greece burst into the open with its collapse, sparking a public debate that drew attention and protest across the empire.55 Arnold Toynbee, the former Foreign Office political intelligence department official, led the attack on British policy in his The Western

49 Marian Kent, ‘Great Britain and the End of the Ottoman Empire, 1900–1923’, in Marian Kent, ed., The Great Powers and the End of the Ottoman Empire (London: Allen & Unwin, 1984), p. 189; V. H. Rothwell, ‘Mesopotamia in British War Aims, 1914–1918’, The Historical Journal, 13 (2009): pp. 273–94 at p. 294.

50 Alex Callinicos, Imperialism and Global Political Economy (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009), p. 2.

51 Baring, Modern Egypt; Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, Atrocities of Justice under British Rule in Egypt (London: T. F. Unwin, 1906).

52 Jay Murray Winter and Antoine Prost, The Great War in History: Debates and Controversies, 1914 to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 13.

53 Jane Dare, Letters from the Forgotten Army (London: Arthur H. Stockwell, 1918), p. 25; Harold Lake, In Salonica with our Army (London: A. Melrose, 1917); Arthur Griffin Tapp, Stories of Salonica and the New Crusade (London: Drane’s, 1922).

54 Hector William Dinning, Nile to Aleppo: With the Light-Horse in the Middle-East (London: Allen & Unwin, 1920); M. S. Briggs, Through Egypt in War-Time (London: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1918).

55 Daniel-Joseph MacArthur-Seal, ‘Intelligence and Lloyd George’s Secret Diplomacy in the Near East, 1920–1922’, The Historical Journal, 56 (2013): pp. 707–28, at p. 725.

Question in Greece and Turkey. 56 Toynbee introduced the familiar critique that western misunderstanding of the peoples of the region was responsible for the failure of foreign policy. His similarly harsh admonition of Greek expansionism and crimes against civilians cost him his recent appointment to the Greek government-funded Koraes chair at Kings College London.57 The sculptor Clare Sheridan, whose association with Bolshevik trade delegates had brought her into conflict with the British High Commissioner in Constantinople, was also unsurprisingly hostile.58 Robert Graves, the Times journalist in the city, saw Britain as having ‘undoubtedly put our money on the wrong horse’.59 Greater sensitivity around publication inhibited most former diplomatic officials from publishing their accounts until years later. The discussion of British policy in former consul at Smyrna Harry Luke’s 1924 memoir Anatolica had none of the candour of the harsh rebukes he issued in correspondence while in his post, for example.60 Those that published later, such as Andrew Ryan, were happy to lay bare divisions among Foreign Office staff on British policy, however.61 Turkish officials and observers also wrote memoirs on the British occupation in the interwar period, which began to appear in Turkish newspapers once they were released from Allied censorship.62 The official history of the War of Independence, as the conflicts of 1919–23 are known in Turkey, was defined by president Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) in his sprawling 1927 speech, of which innumerable editions have now been published.63 Dissenting accounts of these critical years were largely prohibited. The prominent author Halide Edib’s memoirs were published in the United States during her exile following the closure of the opposition Progressive Republican Party, which her husband was a founder of.64 Another member of the short-lived opposition party, the Ottoman and later Turkish National Movement general, Kazım Karabekir, attempted to publish his memoirs of the War of Independence in 1933, but was prevented after police raided the publication house and burnt the first editions of the book, with a limited reprint not published until 1951, after his death.65 Recent interest in memoirs of the First World War has prompted the collection and publication of

56 Arnold Toynbee, The Western Question in Greece and Turkey: A Study in the Contact of Civilisations (London: Constable, 1922).

57 Richard Clogg, Politics and the Academy: Arnold Toynbee and the Koraes Chair (London: Frank Cass, 1986).

58 Clare Sheridan, A Turkish Kaleidoscope (London: Duckworth, 1926), p. 14.

59 Robert Graves, Storm Centres of the Near East: Personal Memories, 1879–1929 (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1933), p. 330.

60 NA, FO 371/5130, ‘Memorandum by Commander Luke on Future Peace with Turkey’, enclosure to de Robeck to Curzon, 7 April 1920; cf. Harry Luke, Anatolica (London: Macmillan, 1924).

61 Andrew Ryan, The Last of the Dragomans (London: G. Bles, 1951), p. 134.

62 A collection of transliterated articles can be found in Mevlut Çelebi, Ahenk ve Halk Gazetelerinde İşgal Hatırları (1919–1922) (Ankara: Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi, 2015).

63 Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Nutuk, 3 vols (Istanbul: Millî Eğitim Basımevi, 1969).

64 Halide Edib Adıvar, The Memoirs of Halide Edib (New York: Century Co., 1926).

65 Kazım Karabekir, İstiklal Harbimizin Esasları (Istanbul: Sinan Matbaası Neşriyat Evi, 1951).

numerous diaries and memoirs that at times include sections on the period of Constantinople’s occupation.66

Writing on the Mediterranean was enlivened by new crises in the later 1920s and 1930s, when Italian expansionism provoked tensions with Britain, France, Greece, and Turkey, and outbreaks of anti-colonial protest and violence mounted in Algeria, Palestine, and Syria.67 The entire sea seemed on the brink of conflict, a situation contrasted with a purportedly peaceable history. In the preface to one such work, Lord Edward Gleichen warned that ‘the kaleidoscope has shifted’ and that ‘No longer is the European coast-line the only one that matters’.68 The German journalist Margaret Boveri, like Gleichen, felt the passing of an era, writing that ‘an abrupt change has come about. The Mediterranean peoples have become dynamic’ and a region that had ‘appeared to exist solely for the sake of tourists and those interested in art’ had been transformed by the ‘parade of military force’.69 Elizabeth Monroe, publishing in the same year as the English edition of Boveri’s work appeared, provided an account of strategic competition in the Mediterranean between France, Britain, and Italy. She remarked how each country’s ‘statesmen proclaim “we must defend our vital interests in the Mediterranean”. We repeat it, like a creed, without enquiring into the nature of the interests.’70

Numerous subsequent historians, however, have not taken Monroe’s warning to heart. British expansion in the eastern Mediterranean is still frequently explained as a logical conclusion to the defence of Britain’s strategic interests, the assumptions behind which evade deconstruction. Thus, Stephen Joseph Stillwell has asserted that the occupation of Constantinople and the straits was ‘the culmination of the traditional British policy of defending this vital waterway’, while Kaya Tuncer Çağlayan in parallel argues that Britain occupied Batoum and Transcaucasia because it ‘had vital interests to protect’.71 Marian Kent likewise presents the division of the Ottoman Empire as Britain ‘exacting the traditional compensation of a victor’.72 Such observations raise the question of why Britain’s

66 İbrahim Hakkı Sunata, İstanbul’da İşgal Yılları (Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2006); Agah Sırrı Levend, Acılar (Ankara: Birleşik Dağıtım Kitabevi, 2012); Mefharet Çetinkaya, İkbal, Yıkım ve İşgal: İstanbul’lu bir Genç Kızın Anıları (Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2013); Cevat Rüştü, İstanbul’un İşgalinde İngiliz Hapishanesi Hatıraları (Istanbul: Sebil Yayınevi, 2009); Cavid Bey, Meşrutiyet Ruznamesi (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 2014); Yorgos Theotokas, Leonis: Bir Dünyanın Merkezindeki Şehir: İstanbul, 1914–1922 (Istanbul: İstos Yayınları, 2013); Nissim M. Benzera, Une Enfance Juive à Istanbul (Istanbul: Isis, 1996); Hagop Mıntzuri, İstanbul Anıları (Istanbul: Aras Yayıncılık, 2017).

67 John Darwin, ‘An Undeclared Empire: The British in the Middle East, 1918–39’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 27 (1999): pp. 159–76, p. 170–2.

68 Edward Gleichen, ‘Foreword’, in E. W. Polson Newman, The Mediterranean and its Problems (London: A. M. Philpot, 1927), p. vii.

69 Margret Boveri, Mediterranean Cross-Currents (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1938), pp. 416–17.

70 Elizabeth Monroe, The Mediterranean in Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1938), p. 2.

71 Stephen Joseph Stillwell, Jr, Anglo-Turkish Relations in the Inter-War Era (New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2003), p. 40.

72 Kent, ‘Great Britain and the End of the Ottoman Empire, 1900–1923’, p. 195.

interests were configured in such a way that eventually untenable occupations appeared to be a desirable strategic policy. After all, British forces evacuated Salonica in 1919, Batoum in 1920, Constantinople in 1923, and significantly reduced their presence in Alexandria and the rest of Egypt in 1922. It is here that British concepts of the nature of the occupied territories and their inhabitants, in this case the Levant and the Levantine, are crucial, making this series of occupations both necessary and possible while determining their shape and duration.

While offering plausible answers as to why Britain chose to occupy or evacuate any given territory, the national interest framework that has dominated discussion of Britain’s presence in the eastern Mediterranean is more limited when asking how Britain ruled. The military regimes established in Alexandria, Salonica, Constantinople, and Batoum developed with little central direction by senior statesmen. The British state’s local representatives were frequently infuriated by having to improvise while a ‘policy of drift’ prevailed in London.73 The cabinet continued to discuss ‘the future of Constantinople’, prevaricated on expanding or evacuating Batoum province, and remained deadlocked over the fate of the protectorate and army of occupation in Egypt. Meanwhile, ad hoc regimes formed by a cocktail of army, navy, and Foreign Office representatives, with varying levels of cooperation with local authorities, constructed a military-imperial regime that, though informal, impacted on the lives of thousands, with at times fatal consequences.

Given the shortcomings of this historiography in addressing the themes pursued by this study, it has been necessary to engage with a broader literature touching topics which are absent from discussions of the locations and years under investigation. Readings from the broader literature on Mediterranean history, urban history, imperialism, orientalism, and cosmopolitanism have been central to grounding understandings of source material, which are assessed using theoretical approaches borrowed from across the social sciences. Such an approach seems particularly suitable for the study of the eastern Mediterranean city, where the exchange and overlap of different worlds is so commonly remarked on, from the writing of nineteenth-century travellers to the guidebooks of the present day, that it has become cliché. These cities’ position within overlapping histories poses challenges for the historian, for the same sites are encountered in divergent literatures: in Greek, Turkish, and Egyptian national historiographies, and are shared between Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, and Ottoman studies, or, increasingly, incorporated into a global focus on selections of cities united by the prefix ‘port-’ or ‘world-’.74

73 King’s College London (KCL), GB 0099 KCLMA Maurice F B, Harington to Maurice, 23 August 1923.

74 Peter Taylor, ‘West Asian/North African Cities in the World City Network: A Global Analysis of Dependence, Integration, and Autonomy’, The Arab World Geographer, 4 (2001): pp. 146–59, at pp. 146–7; Charles Cartier, ‘Cosmopolitics and the Maritime World City’, Geographical Review, 89 (1999): pp. 278–89, at p. 278.