A Walkthrough of the Learning Aids

The pedagogical elements in this book work together to focus on and reinforce key concepts and fundamental principles of programming, with additional tips and detail organized to support and deepen these fundamentals. In addition to traditional features, such as chapter objectives and a wealth of exercises, each chapter contains elements geared to today’s visual learner.

Throughout each chapter, margin notes show where new concepts are introduced and provide an outline of key ideas.

4.3 The for Loop

Annotated syntax boxes provide a quick, visual overview of new language constructs.

It often happens that you want to execute a sequence of statements a given number of times. You can use a while loop that is controlled by a counter, as in the following example: counter = 1; // Initialize the counter while (counter <= 10) // Check the counter { cout << counter << endl; counter++; // Update the counter } Because this loop type is so common, there is a special form for it, called the for loop (see Syntax 4.2). for (counter = 1; counter <= 10; counter++) { cout << counter << endl; } Some people call this loop count-controlled In contrast, the while loop of the preceding section can be called an event-controlled loop because it executes until an event occurs (for example, when the balance reaches the target). Another commonly-used term for a count-controlled loop is de nite You know from the outset that the loop body will be executed a de nite number of times––ten times in our example. In contrast, you do not know how many iterations it takes to accumulate a target balance. Such a loop is called inde nite

Syntax 4.2 for Statement

Annotations explain required components and point to more information on common errors or best practices associated with the syntax.

and contents.

for loop neatly groups the initialization, condition, and update expressions together However, it is important to realize that these expressions are not executed together (see Figure 3).

Analogies to everyday objects are used to explain the nature and behavior of concepts such as variables, data types, loops, and more.

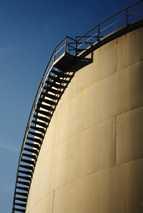

Memorable photos reinforce analogies and help students remember the concepts.

Problem Solving sections teach techniques for generating ideas and evaluating proposed solutions, often using pencil and paper or other artifacts. These sections emphasize that most of the planning and problem solving that makes students successful happens away from the computer

HOW TO 1.1

Describing an Algorithm with Pseudocode

6.5

Problem Solving: Discovering Algorithms by Manipulating Physical Objects 277

Now how does that help us with our problem, switching the first and the second half of the array?

Let’s put the first coin into place, by swapping it with the fifth coin. However, as C++ programmers, we will say that we swap the coins in positions 0 and 4:

This is the rst of many “How To” sections in this book that give you step-by-step procedures for carrying out important tasks in developing computer programs.

Before you are ready to write a program in C++, you need to develop an algorithm—a method for arriving at a solution for a particular problem. Describe the algorithm in pseudocode––a sequence of precise steps formulated in English. To illustrate, we’ll devise an algorithm for this problem:

Problem Statement You have the choice of buying one of two cars. One is more fuel ef cient than the other, but also more expensive. You know the price and fuel ef ciency (in miles per gallon, mpg) of both cars. You plan to keep the car for ten years. Assume a price of $4 per gallon of gas and usage of 15,000 miles per year You will pay cash for the car and not worry about nancing costs. Which car is the better deal?

Step 1 Determine the inputs and outputs.

In our sample problem, we have these inputs:

• purchase price1 and fuel efficiency1, the price and fuel ef ciency (in mpg) of the rst car

• purchase price2 and fuel efficiency2, the price and fuel ef ciency of the second car

WORKED EXAMPLE 1.1

Writing an Algorithm for Tiling a Floor

Problem Statement Your task is to tile a rectangular bathroom oor with alternating black and white tiles measuring 4 × 4 inches. The oor dimensions, are multiples of 4.

Step 1 Determine the inputs and outputs. The inputs are the oor dimensions (length × width), measured in inches. The output is a tiled oor

Step 2 Break down the problem into smaller tasks.

Table 3 Variable Names in C++

A natural subtask is to lay one row of tiles. If you can solve that task, then you can solve the problem by laying one row next to the other, starting from a wall, until you reach the opposite wall. How do you lay a row? Start with a tile at one wall. If it is white, put a black one next to it. If it is black, put a white one next to it. Keep going until you reach the opposite wall. The row will contain width / 4 tiles.

Variable Name Comment

Step 3 Describe each subtask in pseudocode. © rban/iStockphoto

can_volume1 Variable names consist of letters, numbers, and the underscore character.

x In mathematics, you use short variable names such as x or y This is legal in C++, but not very common, because it can make programs harder to understand (see Programming Tip 2.1).

Can_volume Caution: Variable names are case sensitive. This variable name is different from can_volume

6pack Error: Variable names cannot start with a number

can volume Error: Variable names cannot contain spaces.

double Error: You cannot use a reserved word as a variable name.

ltr/fl.oz Error: You cannot use symbols such as or /

How To guides give step-by-step guidance for common programming tasks, emphasizing planning and testing. They answer the beginner’s question, “Now what do I do?” and integrate key concepts into a problem-solving sequence.

Worked Examples apply the steps in the How To to a di erent example, showing how they can be used to plan, implement, and test a solution to another programming problem.

Example tables support beginners with multiple, concrete examples. These tables point out common errors and present another quick reference to the section’s topic.

Next, we swap the coins in positions 1 and 5:

© dlewis33/Getty Images

Consider the function call illustrated in Figure 3: double result1 = cube_volume(2);

• The parameter variable side_length of the cube_volume function is created. ❶

• The parameter variable is initialized with the value of the argument that was passed in the call. In our case, side_length is set to 2. ❷

• The function computes the expression side_length * side_length * side_length, which has the value 8. That value is stored in the variable volume ❸

• The function returns. All of its variables are removed. The return value is transferred to the caller, that is, the function calling the cube_volume function. ❹

1 Function call result1

double result1 = cube_volume(2);

side_length

2 Initializing function parameter variable result1

side_length 2

3 About to return to the caller result1

double

side_length volume = 8 2

4 After function call result1 = 8

Progressive gures trace code segments to help students visualize the program ow. Color is used consistently to make variables and other elements easily recognizable.

Optional engineering exercises engage students with applications from technical elds.

Engineering P7.12 Write a program that simulates the control software for a “people mover” system, a set driverless trains that move in two concentric circular tracks. A set of switches allows trains to switch tracks.

In your program, the outer and inner tracks should each be divided into ten segments. Each track segment can contain a train that moves either clockwise or counterclockwise. A train moves to an adjacent segment in its track or, if that segment is occupied, to the adjacent segment in the other track.

Define a Segment structure. Each segment has a pointer to the next and previous segments in its track, a pointer to the

and previous

Program listings are carefully designed for easy reading, going well beyond simple color coding. Functions are set o by a subtle outline.

Additional example programs are provided with the companion code for students to read, run, and modify.

Common Errors describe the kinds of errors that students often make, with an explanation of why the errors occur, and what to do about them.

Programming Tip 3.6

Hand-Tracing

Common Error 2.1

Programming Tips explain good programming practices, and encourage students to be more productive with tips and techniques such as hand-tracing.

your program, the statements are compiled in order. When the compiler reaches the rst statement, it does not know that liter_per_ounce will be de ned in the next line, and it reports an error.

A very useful technique for understanding whether a program works correctly is called hand-tracing You simulate the program’s activity on a sheet of paper You can use this method with pseudocode or C++ code. Get an index card, a cocktail napkin, or whatever sheet of paper is within reach. Make a column for each variable. Have the program code ready Use a marker, such as a paper clip, to mark the current statement. In your mind, execute statements one at a time. Every time the value of a variable changes, cross out the

value and write the new value below the old one. For example, let’s trace the tax program with the data from the program run in Section 3.4. In lines 13 and 14, tax1 and tax2 are initialized to 0.

Special Topic 6.5

The Range-Based for Loop

C++ 11 introduces a convenient syntax for visiting all elements in a “range” or sequence of elements. This loop displays all elements in a vector: vector<int> values = {1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36}; for (int v : values)

{ cout << v << " "; }

Special Topics present optional topics and provide additional explanation of others.

Computing & Society 7.1 Embedded Systems

An embedded system is a computer system that controls a device. The device contains a processor and other hardware and is controlled by a computer program. Unlike a personal computer which has been designed to be exible and run many di erent computer programs, the hardware and software of an embedded system are tailored to a speci c device. Computer controlled devices are becoming increasingly common, ranging from washing machines to medical equipment, cell phones, automobile engines, and spacecraft. Several challenges are speci c to programming embedded systems. Most importantly, a much higher standard of quality control applies. Vendors are often unconcerned about bugs in personal computer software, because they can always make you install a patch or upgrade to the next version. But in an embedded system, that is not an option. Few consumers

would feel comfortable upgrading the software in their washing machines or automobile engines. If you ever handed in a programming assignment that you believed to be correct, only to have the instructor or grader nd bugs in it, then you know how hard it is to write software that can reliably do its task for many years without a chance of changing it. Quality standards are especially important in devices whose failure would destroy property or endanger human life. Many personal computer purchasers buy computers that are fast and have a lot of storage, because the investment is paid back over time when many programs are run on the same equipment. But the hardware for an embedded device is not shared––it is dedicated to one device. A separate processor, memory, and so on, are built for every copy of the device. If it is possible to shave a few pennies o the manufacturing cost of every unit, the savings can add up quickly for devices that are pro-

duced in large volumes. Thus, the programmer of an embedded system has a much larger economic incentive to conserve resources than the desktop software programmer Unfortunately, trying to conserve resources usually makes it harder to write programs that work correctly. C and C++ are commonly used languages for developing embedded systems.

E XAMPLE C ODE

In each iteration of the loop, v is set to an element of the vector. Note that you do not use an index variable. The value of v is the element, not the index of the element. If you want to modify elements, declare the loop variable as a reference: for (int& v : values)

{ v++; }

This loop increments all elements of the vector You can use the reserved word auto, which was introduced in Special Topic 2.3, for the type of the element variable: for (auto v : values) { cout << v << " "; }

The range-based for loop also works for arrays: int primes[] = { 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13 }; for (int p : primes)

{ cout << p << " "; }

The range-based for loop is a convenient shortcut for visiting or updating all elements of a vector or an array. This book doesn’t use it because one can achieve the same result by looping over index values. But if you like the more concise form, and use C++ 11 or later, you should certainly consider using it.

See special_topic_5 of your companion code for a program that demonstrates the range-based for loop.

Computing & Society presents social and historical topics on computing—for interest and to ful ll the “historical and social context” requirements of the ACM/IEEE curriculum guidelines.

© Courtesy of Professor Prabal Dutta. The Controller of an Embedded System

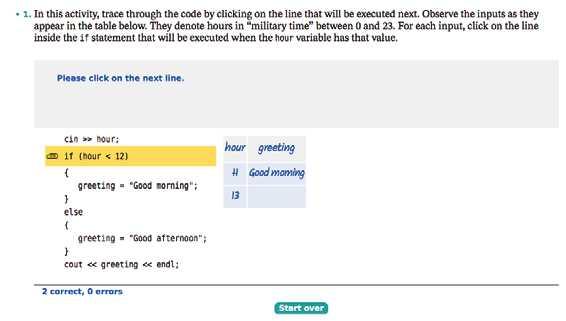

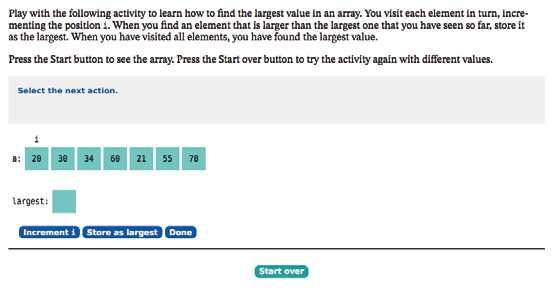

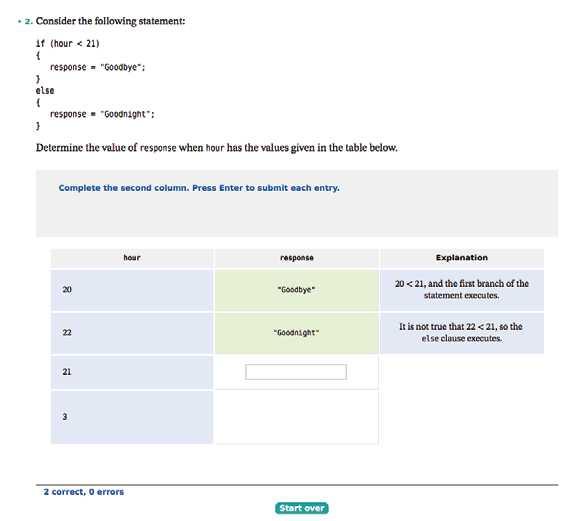

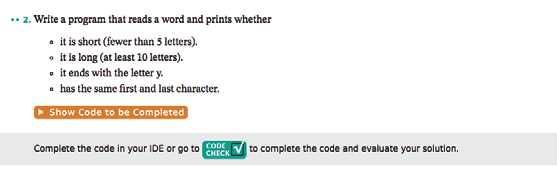

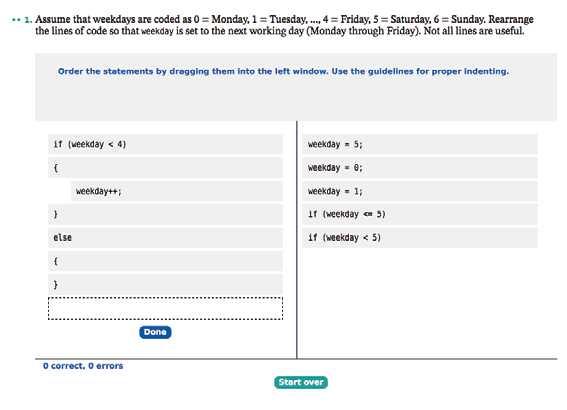

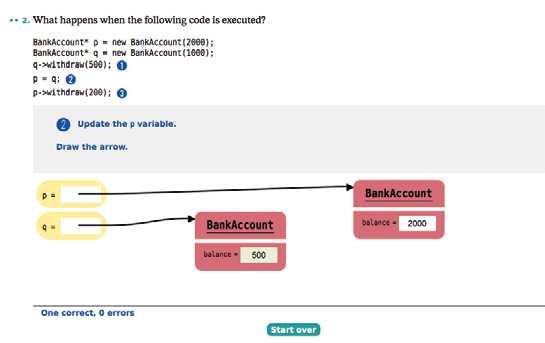

Interactive activities in the E-Text engage students in active reading as they…

Explore common algorithms

Trace through a code segment

Build an example table

Complete a program and get immediate feedback

Arrange code to ful ll a task

Create a memory diagram

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Don Fowley, Graig Donini, Dan Sayre, Ryann Dannelly, David Dietz, Laura Abrams, and Billy Ray at John Wiley & Sons for their help with this project. An especially deep acknowledgment and thanks goes to Cindy Johnson for her hard work, sound judgment, and amazing attention to detail.

I am grateful to Mark Atkins, Ivy Technical College, Katie Livsie, Gaston College, Larry Morell, Arkansas Tech University, and Rama Olson, Gaston College, for their contributions to the supplemental material. Special thanks to Stephen Gilbert, Orange Coast Community College, for his help with the interactive exercises.

Every new edition builds on the suggestions and experiences of new and prior reviewers, contributors, and users. We are very grateful to the individuals who provided feedback, reviewed the manuscript, made valuable suggestions and contributions, and brought errors and omissions to my attention. They include:

Charles D. Allison, Utah Valley State College

Fred Annexstein, University of Cincinnati

Mark Atkins, Ivy Technical College

Stefano Basagni, Northeastern University

Noah D. Barnette, Virginia Tech

Susan Bickford, Tallahassee Community College

Ronald D. Bowman, University of Alabama, Huntsville

Robert Burton, Brigham Young University

Peter Breznay, University of Wisconsin, Green Bay

Richard Cacace, Pensacola Junior College, Pensacola

Kuang-Nan Chang, Eastern Kentucky University

Joseph DeLibero, Arizona State University

Subramaniam Dharmarajan, Arizona State University

Mary Dorf, University of Michigan

Marty Dulberg, North Carolina State University

William E. Duncan, Louisiana State University

John Estell, Ohio Northern University

Waleed Farag, Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Evan Gallagher, Polytechnic Institute of New York University

Stephen Gilbert, Orange Coast Community College

Kenneth Gitlitz, New Hampshire Technical Institute

Daniel Grigoletti, DeVry Institute of Technology, Tinley Park

Barbara Guillott, Louisiana State University

Charles Halsey, Richland College

Jon Hanrath, Illinois Institute of Technology

Neil Harrison, Utah Valley University

Jurgen Hecht, University of Ontario

Steve Hodges, Cabrillo College

Acknowledgments

Jackie Jarboe, Boise State University

Debbie Kaneko, Old Dominion University

Mir Behrad Khamesee, University of Waterloo

Sung-Sik Kwon, North Carolina Central University

Lorrie Lehman, University of North Carolina, Charlotte

Cynthia Lester, Tuskegee University

Yanjun Li, Fordham University

W. James MacLean, University of Toronto

LindaLee Massoud, Mott Community College

Adelaida Medlock, Drexel University

Charles W. Mellard, DeVry Institute of Technology, Irving

Larry Morell, Arkansas Tech University

Ethan V. Munson, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Arun Ravindran, University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Philip Regalbuto, Trident Technical College

Don Retzlaff, University of North Texas

Jeff Ringenberg, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

John P. Russo, Wentworth Institute of Technology

Kurt Schmidt, Drexel University

Brent Seales, University of Kentucky

William Shay, University of Wisconsin, Green Bay

Michele A. Starkey, Mount Saint Mary College

William Stockwell, University of Central Oklahoma

Jonathan Tolstedt, North Dakota State University

Boyd Trolinger, Butte College

Muharrem Uyar, City College of New York

Mahendra Velauthapillai, Georgetown University

Kerstin Voigt, California State University, San Bernardino

David P. Voorhees, Le Moyne College

Salih Yurttas, Texas A&M University

A special thank you to all of our class testers:

Pani Chakrapani and the students of the University of Redlands

Jim Mackowiak and the students of Long Beach City College, LAC

Suresh Muknahallipatna and the students of the University of Wyoming

Murlidharan Nair and the students of the Indiana University of South Bend

Harriette Roadman and the students of New River Community College

David Topham and the students of Ohlone College

Dennie Van Tassel and the students of Gavilan College

CONTENTS

PREFACE v

SPECIAL FEATURES xxiv

QUICK REFERENCE xxviii

INTRODUCTION 1

1.1 What Is Programming? 2

1.2 The Anatomy of a Computer 3

C&S Computers Are Everywhere 5

1.3 Machine Code and Programming

Languages 5

C&S Standards Organizations 7

1.4 Becoming Familiar with Your Programming Environment 7

PT 1 Backup Copies 10

1.5 Analyzing Your First Program 11

CE 1 Omitting Semicolons 13

ST 1 Escape Sequences 13

1.6 Errors 14

CE 2 Misspelling Words 15

1.7

PROBLEM SOLVING Algorithm Design 16

The Algorithm Concept 16

An Algorithm for Solving an Investment Problem 17

Pseudocode 18

From Algorithms to Programs 19

HT 1 Describing an Algorithm with Pseudocode 19

WE 1 Writing an Algorithm for Tiling a Floor 21

FUNDAMENTAL DATA TYPES

25

2.1 Variables 26

Variable Definitions 26

Number Types 28

Variable Names 29

The Assignment Statement 30

Constants 31

Comments 31

CE 2 Using Uninitialized Variables 33

PT 1 Choose Descriptive Variable Names 33

PT 2 Do Not Use Magic Numbers 34

ST 1 Numeric Types in C++ 34

ST 2 Numeric Ranges and Precisions 35

PT 3 Tabs 64 1 2 3

ST 3 Defining Variables with auto 35

2.2 Arithmetic 36

Arithmetic Operators 36

Increment and Decrement 36

Integer Division and Remainder 36

Converting Floating-Point Numbers to Integers 37

Powers and Roots 38

CE 3 Unintended Integer Division 39

CE 4 Unbalanced Parentheses 40

CE 5 Forgetting Header Files 40

CE 6 Roundoff Errors 41

PT 3 Spaces in Expressions 42

ST 4 Casts 42

ST 5 Combining Assignment and Arithmetic 42

C&S The Pentium Floating-Point Bug 43

2.3 Input and Output 44

Input 44

Formatted Output 45

2.4 PROBLEM SOLVING First Do It By Hand 47

WE 1 Computing Travel Time 48

HT 1 Carrying out Computations 48

WE 2 Computing the Cost of Stamps 51

2.5 Strings 51

The string Type 51

Concatenation 52

String Input 52

String Functions 52

C&S International Alphabets and Unicode 55

DECISIONS 59

3.1 The if Statement 60

CE 1 A Semicolon After the if Condition 63

PT 1 Brace Layout 63

PT 2 Always Use Braces 64

CE 1 Using Undefined Variables 33

PT 4 Avoid Duplication in Branches 65

ST 1 The Conditional Operator 65

3.2 Comparing Numbers and Strings 66

CE 2 Confusing = and == 68

CE 3 Exact Comparison of Floating-Point Numbers 68

PT 5 Compile with Zero Warnings 69

ST 2 Lexicographic Ordering of Strings 69

HT 1 Implementing an if Statement 70

WE 1 Extracting the Middle 72

C&S Dysfunctional Computerized Systems 72

3.3 Multiple Alternatives 73

ST 3 The switch Statement 75

3.4 Nested Branches 76

CE 4 The Dangling else Problem 79

PT 6 Hand-Tracing 79

3.5 PROBLEM SOLVING Flowcharts 81

3.6 PROBLEM SOLVING Test Cases 83

PT 7 Make a Schedule and Make Time for Unexpected Problems 84

3.7 Boolean Variables and Operators 85

CE 5 Combining Multiple Relational Operators 88

CE 6 Confusing && and || Conditions 88

ST 4 Short-Circuit Evaluation of Boolean Operators 89

ST 5 De Morgan’s Law 89

3.8 APPLICATION Input Validation 90

C&S Artificial Intelligence 92

4.4 The do Loop 111

PT 4 Flowcharts for Loops 111

4.5 Processing Input 112

Sentinel Values 112

Reading Until Input Fails 114

ST 1 Clearing the Failure State 115

ST 2 The Loop-and-a-Half Problem and the break Statement 116

ST 3 Redirection of Input and Output 116

4.6 PROBLEM SOLVING Storyboards 117

4.7 Common Loop Algorithms 119

Sum and Average Value 119

Counting Matches 120

Finding the First Match 120

Prompting Until a Match is Found 121

Maximum and Minimum 121

Comparing Adjacent Values 122

HT 1 Writing a Loop 123

WE 1 Credit Card Processing 126

4.8 Nested Loops 126

WE 2 Manipulating the Pixels in an Image 129

4.9 PROBLEM SOLVING Solve a Simpler Problem First 130

4.10 Random Numbers and Simulations 134

Generating Random Numbers 134

Simulating Die Tosses 135

The Monte Carlo Method 136

C&S Digital Piracy 138

4 5

LOOPS 95

4.1 The while Loop 96

CE 1 Infinite Loops 100

CE 2 Don’t Think “Are We There Yet?” 101

CE 3 Off-by-One Errors 101

C&S The First Bug 102

4.2 PROBLEM SOLVING Hand-Tracing 103

4.3 The for Loop 106

PT 1 Use for Loops for Their Intended Purpose Only 109

PT 2 Choose Loop Bounds That Match Your Task 110

PT 3 Count Iterations 110

FUNCTIONS 141

5.1 Functions as Black Boxes 142

5.2 Implementing Functions 143

PT 1 Function Comments 146

5.3 Parameter Passing 146

PT 2 Do Not Modify Parameter Variables 148

5.4 Return Values 148

CE 1 Missing Return Value 149

ST 1 Function Declarations 150

HT 1 Implementing a Function 151

WE 1 Generating Random Passwords 152

WE 2 Using a Debugger 152

5.5 Functions Without Return Values 153

5.6 PROBLEM SOLVING Reusable Functions 154

5.7 PROBLEM SOLVING Stepwise

Refinement 156

PT 3 Keep Functions Short 161

PT 4 Tracing Functions 161

PT 5 Stubs 162

WE 3 Calculating a Course Grade 163

5.8 Variable Scope and Global Variables 163

PT 6 Avoid Global Variables 165

5.9 Reference Parameters 165

PT 7 Prefer Return Values to Reference Parameters 169

ST 2 Constant References 170

5.10 Recursive Functions (Optional) 170

HT 2 Thinking Recursively 173

C&S The Explosive Growth of Personal Computers 174

ARRAYS AND VECTORS 179

6.1 Arrays 180

Defining Arrays 180

Accessing Array Elements 182

Partially Filled Arrays 183

CE 1 Bounds Errors 184

PT 1 Use Arrays for Sequences of Related Values 184

C&S Computer Viruses 185

6.2 Common Array Algorithms 185

Filling 186

Copying 186

Sum and Average Value 186

Maximum and Minimum 187

Element Separators 187

Counting Matches 187

Linear Search 188

Removing an Element 188

Inserting an Element 189

Swapping Elements 190

Reading Input 191

ST 1 Sorting with the C++ Library 192

ST 2 A Sorting Algorithm 192

ST 3 Binary Search 193

6.3 Arrays and Functions 194

6.4 PROBLEM SOLVING Adapting Algorithms 198

HT 1 Working with Arrays 200

WE 1 Rolling the Dice 203

6.5 PROBLEM SOLVING Discovering Algorithms by Manipulating Physical Objects 203

6.6 Two-Dimensional Arrays 206

Defining Two-Dimensional Arrays 207

Accessing Elements 207

Locating Neighboring Elements 208

Computing Row and Column Totals 208

Two-Dimensional Array Parameters 210

CE 2 Omitting the Column Size of a TwoDimensional Array Parameter 212

WE 2 A World Population Table 213

6.7 Vectors 213

Defining Vectors 214

Growing and Shrinking Vectors 215

Vectors and Functions 216

Vector Algorithms 216

7.1

ST 3 Constant Pointers 235 6 7

ST 4 Constant Array Parameters 198

Two-Dimensional Vectors 218

PT 2 Prefer Vectors over Arrays 219

ST 5 The Range-Based for Loop 219

POINTERS AND STRUCTURES 223

Defining and Using Pointers 224

Defining Pointers 224

Accessing Variables Through Pointers 225

Initializing Pointers 227

CE 1 Confusing Pointers with the Data to Which They Point 228

PT 1 Use a Separate Definition for Each Pointer Variable 229

ST 1 Pointers and References 229

7.2 Arrays and Pointers 230

Arrays as Pointers 230

Pointer Arithmetic 230

Array Parameter Variables Are Pointers 232

ST 2 Using a Pointer to Step Through an Array 233

CE 2 Returning a Pointer to a Local Variable 234

PT 2 Program Clearly, Not Cleverly 234

7.3 C and C++ Strings 235

The char Type 235

C Strings 236

Character Arrays 237

Converting Between C and C++ Strings 237 C++ Strings and the [] Operator 238

ST 4 Working with C Strings 238

7.4 Dynamic Memory Allocation 240

CE 3 Dangling Pointers 242

CE 4 Memory Leaks 243

7.5 Arrays and Vectors of Pointers 243

7.6 PROBLEM SOLVING Draw a Picture 246

HT 1 Working with Pointers 248

WE 1 Producing a Mass Mailing 249

C&S Embedded Systems 250

7.7 Structures 250

Structured Types 250

Structure Assignment and Comparison 251

Functions and Structures 252

Arrays of Structures 252

Structures with Array Members 253

Nested Structures 253

7.8 Pointers and Structures 254

Pointers to Structures 254

Structures with Pointer Members 255

ST 5 Smart Pointers 256

STREAMS 259

8.1 Reading and Writing Text Files 260

Opening a Stream 260

Reading from a File 261

Writing to a File 262

A File Processing Example 262

8.2 Reading Text Input 265

Reading Words 265

Reading Characters 266

Reading Lines 267

CE 1 Mixing >> and getline Input 268

ST 1 Stream Failure Checking 269

8.3 Writing Text Output 270

ST 2 Unicode, UTF-8, and C++ Strings 272

8.4 Parsing and Formatting Strings 273

8.5 Command Line Arguments 274

C&S Encryption Algorithms 277

HT 1 Processing Text Files 278

WE 1 Looking for for Duplicates 281

8.6 Random Access and Binary Files 281

Random Access 281

Binary Files 282

Processing Image Files 282

C&S Databases and Privacy 286

CLASSES 289

9.1 Object-Oriented Programming 290

9.2 Implementing a Simple Class 292

9.3 Specifying the Public Interface of a Class 294

CE 1 Forgetting a Semicolon 296

9.4 Designing the Data Representation 297

9.5 Member Functions 299

Implementing Member Functions 299

Implicit and Explicit Parameters 299 Calling a Member Function from a Member Function 301

PT 1 All Data Members Should Be Private; Most Member Functions Should Be Public 303

PT 2 const Correctness 303

9.6 Constructors 304

CE 2 Trying to Call a Constructor 306

ST 1 Overloading 306

ST 2 Initializer Lists 307

ST 3 Universal and Uniform Initialization Syntax 308

9.7 PROBLEM SOLVING Tracing Objects 308

HT 1 Implementing a Class 310

WE 1 Implementing a Bank Account Class 314

C&S Electronic Voting Machines 314

9.8 PROBLEM SOLVING Discovering Classes 315

PT 3 Make Parallel Vectors into Vectors of Objects 317

9.9 Separate Compilation 318

9.10 Pointers to Objects 322

Dynamically Allocating Objects 322

The -> Operator 323

The this Pointer 324 8 9

9.11 PROBLEM SOLVING Patterns for

Object Data 324

Keeping a Total 324

Counting Events 325

Collecting Values 326

Managing Properties of an Object 326

Modeling Objects with Distinct States 327

Describing the Position of an Object 328

C&S Open Source and Free Software 329

INHERITANCE 333

10.1 Inheritance Hierarchies 334

10.2 Implementing Derived Classes 338

CE 1 Private Inheritance 341

CE 2 Replicating Base-Class Members 341

PT 1 Use a Single Class for Variation in Values, Inheritance for Variation in Behavior 342

ST 1 Calling the Base-Class Constructor 342

10.3 Overriding Member Functions 343

CE 3 Forgetting the Base-Class Name 345

10.4 Virtual Functions and Polymorphism 346

The Slicing Problem 346

Pointers to Base and Derived Classes 347

Virtual Functions 348

Polymorphism 349

PT 2 Don’t Use Type Tags 352

CE 4 Slicing an Object 352

CE 5 Failing to Override a Virtual Function 353

ST 2 Virtual Self-Calls 354

HT 1 Developing an Inheritance Hierarchy 354

WE 1 Implementing an Employee Hierarchy for Payroll Processing 359

C&S Who Controls the Internet? 360

APPENDIx A RESERVED WORD SUMMARY A-1

APPENDIx B OPERATOR SUMMARY A-3

APPENDIx C CHARACTER CODES A-5

APPENDIx D C++ LIBRARY SUMMARY A-8

APPENDIx E C++ LANGUAGE CODING GUIDELINES A-11

APPENDIx F NUMBER SYSTEMS AND BIT AND SHIFT OPERATIONS (E-TExT ONLY)

GLOSSARY G-1

INDEx I-1

CREDITS C-1

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF SYNTAx BOxES

Assignment 30 C++ Program 12

Class Definition 295 Comparisons 67

Constructor with Base-Class Initializer 342

Defining an Array 181 Defining a Structure 251 Defining a Vector 213 Derived-Class Definition 340 Dynamic Memory Allocation 240 for Statement 106 Function Definition 145 if Statement 61 Input Statement 44 Member Function Definition 301 Output Statement 13 Pointer Syntax 226 Two-Dimensional Array Definition 207 Variable Definition 27 while Statement 97 Working with File Streams 262

Variable and Constant De nitions

Type Name Initial value

int cans_per_pack = 6;

const double CAN_VOLUME = 0.335;

Mathematical Operations

#include <cmath>

pow(x, y) Raising to a power x y

sqrt(x) Square root x log10(x) Decimal log log10(x)

abs(x) Absolute value | x|

sin(x)

cos(x) Sine, cosine, tangent of x (x in radians)

tan(x)

Selected Operators and Their Precedence

(See Appendix B for the complete list.)

[] Array element access ++ -- ! Increment, decrement, Boolean not * / % Multiplication, division, remainder + - Addition, subtraction < <= > >= Comparisons == != Equal, not equal && Boolean and || Boolean or = Assignment

Loop Statements

Condition

while (balance < TARGET)

{ year++; balance = balance * (1 + rate / 100);

} for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

Initialization Condition Update

{ cout << i << endl; } do { cout << "Enter a positive integer: "; cin >> input;

Loop body executed at least once

Conditional Statement

Condition

if (floor >= 13)

{ actual_floor = floor - 1; } else if (floor >= 0)

{ actual_floor = floor;

} else

} while (input <= 0);

Executed when condition is true

Second condition (optional)

{ cout << "Floor negative" << endl; }

String Operations

#include <string> string s = "Hello"; int n = s.length(); // 5 string t = s.substr(1, 3); // "ell" string c = s.substr(2, 1); // "l" char ch = s[2]; // 'l' for (int i = 0; i < s.length(); i++)

{ string c = s.substr(i, 1); or char ch = s[i]; Process c or ch }

Function De nitions

Return type

Executed when all conditions are false (optional)

Parameter type and name

double cube_volume(double side_length)

{ double vol = side_length * side_length * side_length; return vol;

}

Reference parameter

Executed while condition is true

Exits function and returns result.

void deposit(double& balance, double amount)

{ balance = balance + amount; }

Modifies supplied argument

Arrays

Element type Length

int numbers[5]; int squares[] = { 0, 1, 4, 9, 16 }; int magic_square[4][4] =

{ { 16, 3, 2, 13 }, { 5, 10, 11, 8 }, { 9, 6, 7, 12 }, { 4, 15, 14, 1 }

};

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++)

{ Process numbers[i] }

Vectors

#include <vector>

Element type

Initial

values (C++ 11)

vector<int> values = { 0, 1, 4, 9, 16 };

Initially empty

Add elements to the end

vector<string> names; names.push_back("Ann"); names.push_back("Cindy"); // names.size() is now 2 names.pop_back(); // Removes last element names[0] = "Beth"; // Use [] for element access

Pointers

int n = 10; int* p = &n; // p set to address of n *p = 11; // n is now 11

Range-based for Loop

An array, vector, or other container (C++ 11)

for (int v : values) { cout << v << endl; }

Output Manipulators

#include <iomanip>

endl Output new line fixed Fixed format for oating-point

setprecision(n) Number of digits after decimal point for xed format

setw(n) Field width for the next item left Left alignment (use for strings) right Right alignment (default)

setfill(ch) Fill character (default: space)

Class De nition

int a[5] = { 0, 1, 4, 9, 16 }; p = a; // p points to start of a *p = 11; // a[0] is now 11 p++; // p points to a[1] p[2] = 11; // a[3] is now 11

class BankAccount

{ public: BankAccount(double amount); void deposit(double amount); double get_balance() const; ... private: double balance; };

Constructor declaration

Member function declaration

Accessor member function Data member Member function definition

void BankAccount::deposit(double amount) { balance = balance + amount; }

Input and Output

#include <iostream> cin >> x; // x can be int, double, string cout << x;

while (cin >> x) { Process x } if (cin.fail()) // Previous input failed

#include <fstream>

string filename = ...; ifstream in(filename); ofstream out("output.txt");

string line; getline(in, line); char ch; in.get(ch);

Inheritance

Derived class Base class

class CheckingAccount : public BankAccount { public: void deposit(double amount); private: int transactions; };

Member function overrides base class

Added data member in derived class Calls base class member function

void CheckingAccount::deposit(double amount) { BankAccount::deposit(amount); transactions++; }