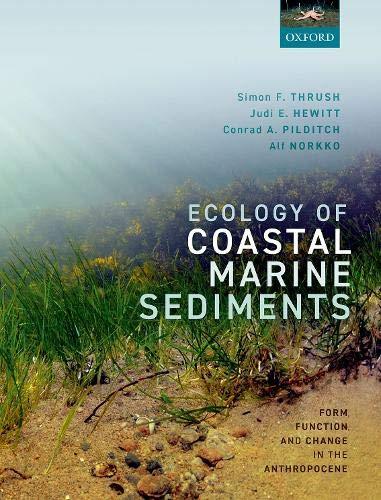

Break All the Borders

Separatism and the Reshaping of the Middle East

ARIEL I. AHRAM

1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ahram, Ariel I. (Ariel Ira), 1979- author.

Title: Break all the borders: separatism and the reshaping of the Middle East/Ariel I. Ahram.

Description: New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018030695 | ISBN 9780190917371 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780190917388 (pb : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Arab countries—History—Autonomy and independence movements. | Separatist movements. | Arab countries—History—21st century. | Arab countries—History—20th century.

Classification: LCC DS39.3 .A36 2019 | DDC 909/.0974927082—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018030695

Paperback printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

We visited some two thousand places, many of which were almost unknown, many of which proved unacceptable. . . . The imaginary universe is a place of astonishing richness and diversity: here are worlds created to satisfy an urgent desire for perfection.

—Alberto Manguel,

The Dictionary of Imaginary Places

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction 1

1. The Rise and Decline of Arab Statehood, 1919 to 2011 19

2. 2011: Revolutions in Arab Sovereignty 43

3. Cyrenaica 69

4. Southern Yemen 95

5. Kurdistan 121

6. The Islamic State 161

Conclusion: The Ends of Separatism in the Arab World 199

End Notes 207 Index 261

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In the course of researching and writing this book, I have incurred considerable debts personal and professional. Hopefully, my talented coauthors—Ellen Lust, Barak Mendelsohn, Rudra Sil, Patrick Köllner, Mara Revkin, Harris Mylonas, and John Gledhill—rubbed off on me. Writing a book this broad in scope required consultation with country experts, many of whom indulged me with their time and insights far beyond what I could have reasonably asked. Fred Wehrey, Osama Abu Buera, and Lisa Anderson were kind enough to share their insights on Libya. Nadwa al-Dawsari, Ian Hartshorn, April L. Alley, and Stacey Yadav answered innumerable questions about Yemen. Amatzia Baram, Steve Heydemann, Kevin Mazur, Ranj Alaaldin, Avi Rubin, Daniel Neep, Harith alQarawee, and David Patel deepened my education on Syria and Iraq. Ranj Alaaldin and Pishtiwan Jalal gave me a crash course on Kurdish politics. Any mistakes are mine, not theirs. I also wish to thank Sam Parker, Miki Fabry, Marc Lynch, Amaney Jamal, Jonathan Wyrtzen, Elizabeth Thompson, Mahdi el Rabab, Ryan Saylor, Arnaud Kurze, Mohammed Tabaar, Dina Khoury, Benjamin Smith, Amy Myers Jaffe, and Charles Tripp for their conversation and encouragement. Charles King, Gabe Rubin, and Sara Goodman provided me kind and thoughtful advice about how to structure the manuscript. I particularly thank Rachel Templer for helping to make this manuscript readable. Thanks also to David McBride and Oxford University Press for taking a chance on difficult material.

Different versions of this paper benefited from presentation at the Weiser Center for Emerging Democracies at Michigan, the Program on Governance and Local Development at Yale, the Bobst Center for Peace and Justice at Princeton, the Program in International Relations at New York University, and the American University in Cairo. Thanks to Marc Lynch and Lauren Baker at the Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) for providing opportunities and venues to discuss these topics. I was fortunate to spend nine months

as a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, one of the most fruitful endeavors of my professional life. I thank Henri Barkey, Rob Litwak, Chris Davenport, Marina Ottaway, David Ottaway, and the Wilson Center library staff, as well as my research assistants, Adena Moulton, Adnan Hussein, Chelsea Burris, and Taha Poonwala.

I have the good fortune to work with excellent students and colleagues at Virginia Tech’s School of Public and International Affairs in Alexandria. I thank Greg Kruczek, Nahom Kasay, Giselle Datz, Joel Peters, David Orden, Patrick Roberts, Anne Khademian, Tim Luke, and Gerard Toal. Special thanks are due to Bruce Pencek and the university library. I gratefully thank the Institute for Society, Culture and Environment at Virginia Tech and the Carnegie Corporation of New York for funding the book’s research and writing.

Due to the insanity of traffic in Washington, DC, much of the final composition took place in the friendly confines of Ohr Kodesh Congregation. I thank Jerry Kiewe and his staff for allowing me to treat the synagogue as a second office.

Finally, this book would be impossible without the love of a wonderful family. My mother, Judi Ahram, continues to be a voice of encouragement for me. Though it pains me to admit this as a writer, my wife, Marni, means more to me than I can put into words. Leonie, my eldest daughter, kindly offered her version of cover art for this project. I regretfully declined. My youngest daughter, Tillie (Matilda), has been waiting her entire life for me to finish a book that would mention her by name. I thank her for her patience.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ADM Assyrian Democratic Movement

ASMB Abu Salim Martyrs Brigade

AQAP Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

AQI Al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia/Iraq

CDF Cyrenaica Defense Forces

CPB Cyrenaica Political Bureau

CTC Cyrenaica Transitional Council

CUP Committee of Union and Progress

DFNS Democratic Federation of Northern Syria

DPA Declaration of Principles and Accord (Yemen)

DRY Democratic Republic of Yemen

FLOSY Front for the Liberation of the Occupied South Yemen

FoS Friends of Syria

FoY Friends of Yemen

FSA Free Syrian Army

GCC Gulf Cooperation Council

GNA Government of National Accord (Libya)

GNC General National Congress (Libya)

GPC General People’s Congress (Yemen)

HNC Hadramawt National Council

HoR House of Representatives (Libya)

IKF Iraqi Kurdistan Front

INC Iraqi National Congress

IS Islamic State (ad-Dawla al-Islamiyya)

JAN Jabhat al-Nusra

JRTN Jaysh Rijal Tariqat Naqshbandi (Army of the Men of the Naqshbandi Order)

KDP Kurdish Democratic Party (Iraq)

KNC Kurdish National Council (Syria)

KRG Kurdish Regional Government (Iraq)

KRI Kurdish Region of Iraq

KRM Kurdish Republic of Mahabad

LCC Local Coordinating Committees (Syria)

LCG Libya Contact Group

LIFG Libyan Islamic Fighting Group

LNA Libyan National Army

MENA Middle East and North Africa

NCC National Coordination Council (Syria)

NDB National Defense Battalion

NDC National Dialogue Conference (Yemen)

NFZ No-fly Zone

NLF National Liberation Front (Yemen)

OLOS Organization for the Liberation of the Occupied South Yemen

PDRY People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen

PFG Petroleum Facilities Guard (Libya)

PKK Kurdistan Workers’ Party

PLO Palestine Liberation Organization

PMU Popular Mobilization Units (Iraq)

PRSY People’s Republic of South Yemen

PUK Patriotic Union of Kurdistan

PYD Democratic Union Party (Syria)

SAL South Arabian League

SCIRI Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq

SDF Syrian Democratic Forces

SM Southern Movement

SNC Syrian National Council

SOC National Coalition for Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces

SPKI Socialist Party of Kurdistan in Iraq

STC Southern Transitional Council (Yemen)

TNC Transitional National Council (Libya)

UN United Nations

UNSCR UN Security Council Resolution

YPG People’s Protection Unit

YSP Yemen Socialist Party

Break All the Borders

Introduction

#Sykespicotover

Strolling amid the rubble of an abandoned military post somewhere along the Syrian-Iraqi boundary, Abu Sufiyya had reason to boast. “This is the so-called border of Sykes-Picot,” he said, referring to the secret 1916 agreement to divide the Ottoman Empire into English, French, and Russian spheres of influence. “Hamdullah [praise God], we don’t recognize it and we will never recognize it. This is not the first border we will break. God willing [inshallah], we will break all the borders.”1 Where Iraq and Syria’s red, green, and black tricolors had flown side by side like fraternal twins for nearly nine decades, now the black flag of the Islamic State (IS) stood alone, emblazoned in austere calligraphy: No God but God. The summer of 2014 was the apogee for IS. Working from its stronghold in eastern Syria and western Iraq, IS’s forces stormed Nineveh Province and seized Iraq’s second-largest city, Mosul. This put IS in control of an archipelago of dust-bitten towns and riparian cities, dams, oil depots, and desert trade routes spanning some 12,000 square miles (31,000 km2). In place of the Syrian and Iraqi governments, IS announced itself as a caliphate, the direct successor to the Prophet Muhammad’s medieval Arabian state. The colonially implanted state system, IS propagandists opined, divided and weakened the unitary Muslim people. They had allowed Western powers to dominate them and permitted infidels, atheists, and religiously deviant Shi’is to rule. Within the new caliphate, though, orthodox “Muslims are honored, infidels disgraced.” IS called on Muslims worldwide to join them in revolt, either by emigrating or building IS colonies in other countries.2 IS propagandists flooded social media with images of bulldozers demolishing border crossings and ripping apart fences. They even introduced a catchy hashtag: #sykespicotover. 3 IS was hardly the only group intent on breaking borders in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).4 Abutting IS-controlled territory, Kurdish leaders seized upon the opportunities of civil war and state failure to gain unprecedented levels of autonomy in Syria and Iraq. Massoud Barzani, president of the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq, told a newspaper in 2015 that

forced division cannot last indefinitely. Instead of the Sykes-Picot border, the new border is drawn in blood. . . . A new Iraq must be formulated. The former Iraq has failed. . . . Look at what is happening in Yemen and look at what is happening in Syria. Other countries have tribal and regional problems, such as Libya. The decades-old equations of World War I were shaken with violence.5

At the bottom of the Arabian Peninsula, members of the Southern Movement (al-Hirak al-Janubi) in Yemen seized the opportunity of civil war to claim a new state, tied to the memory of the once-independent South Yemen. Concurrently, in eastern Libya a federalist movement demanded autonomy, if not outright selfgovernance, for the once-independent Cyrenaica (Barqa). These uprisings represent the latest in a century of strife in the Arab world. As soon as regional states were conceived, there were calls to abort them. The systems of rule and political boundaries that appeared in the Arab world seemed incongruent with popular identities and aspirations. As a result, for the last century Arab states have endured a maelstrom of wars, revolutions, coups, and insurrections.6 Much of the blame for the region’s malformed states, as IS propagandists demonstrate, is laid at the feet of two men—François Georges-Picot and Sir Mark Sykes. Picot trained as a lawyer and joined the French diplomatic corps, serving as consul general in Beirut. Sykes, heir to a Yorkshire baronetcy, dropped out of Cambridge, wrote books, fought in the Boer War, and served in Parliament. Working under Lord Kitchener during the Great War, Sykes took a hand in Britain’s Near Eastern policies. Picot and Sykes met several times in 1915 and 1916 to discuss the disposition of the Ottoman domains once the war ended. The document that would forever be associated with their names was signed in St. Petersburg in February 1916 in consultation with the Russian Foreign Ministry, which had its own designs on the Caucasus and Black Sea region. The agreement was supposed to be secret. It only came to light because the Bolsheviks, eager to embarrass the Allies, released the classified diplomatic correspondence in November 1917. As memorialized in a thousand-word memo and a finely hued watercolor map, they agreed to French control over southern Anatolia and the northern Levant, where they had a long-standing relationship with the Maronite Christian community around Mount Lebanon. Britain would hold sway over the southern linkages between Baghdad and the Persian Gulf through to the port of Haifa.

A century later, Sykes-Picot is discussed as MENA’s original sin, the root of its malformed states and malignant politics. Yet this is a bad historical caricature. For one thing, Sykes and Picot discussed not states but rather zones of colonial control. These colonial footprints were significant, but rarely conclusive, in determining the course of state formation. This jaundiced view also slights the

agency of indigenous actors who authored their own drives to statehood and tried simultaneously to take advantage of and resist colonial encroachment.7 Additionally, this view overlooks the role of new norms of self-determination and popular sovereignty in inspiring and substantiating statehood. These ideas, propounded by Woodrow Wilson at the end of World War I, became core principles of international society. International institutions like the League of Nations, Wilson’s brainchild, and the United Nations, articulated these norms as they orchestrated the transition from colonialism to independence. The emergence and endurance of Arab states, therefore, were part and parcel of the crystallization of mid-century liberal internationalism.

Still, the Ottomans used the leaked documents to embarrass Arab rebels like Emir Faisal bin Hussein al-Hashemi, who had cast their lot with the infidel British instead of fellow Muslims. Arab leaders were outraged at what they saw as Britain’s double-dealing, realizing that the agreement undercut promises to support an Arab kingdom.8 The agreement blocked the possibilities of establishing states based on regions’ presumed organic unity, under the aegis of either Arab nationalism or pan-Islam. Discussing the impact of Sykes-Picot during a private meeting with Saddam Hussein in 1988, Iraq’s foreign minister commented derisively (and largely erroneously) that “Lebanon, which is the size of an Arab county, became a state. . . . Qatar, which is a small, tiny municipality, is now spoken of as one with history, culture, and literature of its own. It is like someone comes and talks about the inhabitants of Mahmoodiya [a small Iraqi city] . . . the history, literature, and culture of Mahmoodiya!”9 In a 1998 epistle, Osama bin Laden used similar terms, calling Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Sudan “paper mini-states.”10 On the eve of the 2003 Iraq war, he directly blamed the SykesPicot Agreement for bringing about the “the dissection of the Islamic world into fragments” and pronounced the American-led campaign against Iraq “a new Sykes-Picot agreement” aimed at the “destroying and looting of our beloved Prophet’s umma [people].”11 As his country descended into civil war in 2012, Syrian president Bashar al-Assad said, “What is taking place in Syria is part of what has been planned for the region for tens of years, as the dream of partition is still haunting the grandchildren of Sykes–Picot.”12

The Sykes-Picot Agreement takes on a subtly different meaning in Western discourse. Whereas the Arab nationalists and pan-Islamists faulted the agreement for creating states that were too small, the Western pundits saw these states as too large. Colonialists clumsily lumped too many fractious primordial ethnosectarian communities together. In the Western imagination, breaking the SykesPicot border would yield not a single coherent mega-state but a plethora of more compact states, their borders fitted to individual ethno-sectarian communities. Instead of a single Gulliver, they anticipated a multitude of Lilliputians. In early 2008, an Atlantic magazine cover showed a regional map featuring potential

states like the Islamic Holy State of the Hijaz, the Alawite Republic, and distinct Sunni and Shi’i states in Mesopotamia. The accompanying article asked: “How many states will there one day be between the Mediterranean and the Euphrates River? Three? Four? Five? Six?”13 Seasoned journalist Robin Wright speculated that Libya, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen could readily splinter into fourteen states.14 Yaroslav Trofimov, another veteran observer of the region, asked, “Where exactly would you draw the lines? And at what cost?”15

This book is about the separatist movements that have tried to change states at a fundamental, territorial level since the 2011 Arab uprisings. “Separatism” is a sterile term for movements that are typically politically dynamic and incendiary. Within the Arab world, incumbent regimes sometimes denigrate their enemies as “separatists” (infasilun). Few groups refer to themselves that way, however, preferring instead “freedom fighters” or “movements of national liberation.” I use “separatist” to mean those groups taking unilateral steps to break away from an existing state and attain some form of self-governance over territory. Secession is the fullest form of separatism. Secessionists seek to quit a parent state and establish a fully independent sovereign entity. But separatism also encompasses extra-legal movements demanding control over legislation, resources, and the means of coercion in a territory. Separatists defy the central government, typically when the state is too weak to resist. While such groups stop short of calling for independence, they displace state sovereignty in function, if not in form.16

The central puzzle is why these conflicts erupted and how separatist movements used the opportunity of state weakness to assert or expand territorial control. Arab politics is often stereotyped as a contest of ancient clans, tribes, and sects masquerading under the banner of modern states and political parties.

“Sykes-Picot” is a metaphor gesturing to that fundamental mismatch between deep primordial identities and contemporary political institutions.17 But why do separatists appear, expand, or entrench in certain conditions and not in others?

Given the presumed ubiquity of sub-state identities, the region should be rife with separatist rebellions seeking to break every border. Yet most of the rebels involved in the 2011 uprisings sought to overthrow individual rulers and regimes and did not contest the territorial integrity of the state. Why and how do some rebel actors seek territorial separation while others seek to control the entire state?

The book argues that the legacies of early- and mid-twentieth-century state building in the MENA region are key factors in both fostering and constraining separatist conflicts. Separatism, therefore, does not spell descent into ethnosectarian pandemonium, or resurgence of primordial identities, of either the macro or micro variety. On the contrary, separatists resurrect prior state-building efforts that drew inspiration from what Erez Manela calls the “Wilsonian moment” and the norms of self-determination.18 Although many of these efforts

failed to attain statehood, they laid the foundation for future separatist struggles. The legacy of these “conquered” or “missing” states worked through two distinct but often interlinked mechanisms. First, at the domestic or internal level, the memories of conquered states provided an institutional focal point for mobilizations against existing political regimes. Failures were not forgotten. On the contrary, they left faint but indelible imprints and could be recalled and reimagined in collective and institutional memory. Separatists used these memories to galvanize and mobilize domestic constituencies. Second, at the international or external level, prior statehood provided separatists a platform from which to address the international community and appeal for its material and moral support. The fact that existing states were built on the graves of discarded ones suggested that the current constellation of states was contingent and dispensable. The international community, therefore, was more amenable to arguments about eventually—and perhaps inevitably—replacing dysfunctional states, opening up the possibilities for a new Wilsonian moment to arise. With each step toward regional disarray, the prospects for separatism came tantalizingly closer. As with any self-fulfilling prophecy, the more the overturning of Sykes-Picot and the demise of existing states was contemplated, the more realistic such outcomes became.19 But what would come next?

This question is of great policy significance, as the people inside and outside the region struggle with instability in MENA. This book shows that disintegration did not affect every state equally and did not lead to hysterical fragmentation. Separatism only took root in certain kinds of states at specific moments of crisis. The ultimate fate of separatists, though, depended as much on their own actions as on external involvement in their conflicts. The United States, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and other actors quickly inducted separatist movements as proxies in their larger campaigns for regional hegemony.20 While this strategy was sometimes successful in the short term, however, its overall impact on stability was dire. Separatists believed that by assisting great powers and abiding by international norms, they would “earn” sovereignty and recognition.21 So far, however, none of these groups have been rewarded with statehood. The quest to rectify the mistakes of the first Wilsonian moment therefore continues.

Moving forward, regional order will require a reorientation of the entire regional system, including its integration with the larger international society. As Raymond Hinnebusch put it, “While Middle East states help make their own regional international society, they do so in conditions not of their own making.”22 Outside actors play a critical role in establishing—or violating—standards of conduct conducive to peace. Stability can only arrive through redefining the formulae by which sovereignty is granted and how states themselves are organized. Without such a redefinition, statehood itself may be doomed, replaced by other political models.

Separatism, Sovereignty, and the Making and Unmaking of States

Making and unmaking states involves a double transformation. On one hand, states maintain and enforce order. In a lecture delivered during Germany’s post–World War I turmoil, Max Weber defined the state as a political entity that successfully claims “the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.”23 States are first and foremost providers of security. The weakening or collapse of the state necessarily involves a breakdown of this monopoly. In such anarchic conditions, people are forced either to submit to or to invent new institutions to provide for security. Separatists are among the actors trying to build new institutions that can assert physical domination over territories in lieu of the state.

Yet, as Weber himself understood, the legitimacy of a state’s claim to dominance depends on its accordance with the norms, identity, and culture of its population. Historically, rulers have legitimated their rule in myriad ways. But in the modern era, by far the most prominent and potent has been through nationalism. The long-running debate between primordialists and constructivists as to the origins and nature of national identity has now reached an uneasy truce. Some nations may be more ancient than others, but all nations emerge in relation to the power of state institutions.24 In the post-colonial world especially, state institutions are key propagators and promoters of particular notions of national identity, at once emphasizing and synthesizing the organic connection between ruler and ruled. Moreover, elites often use these institutions to shape citizens’ self-perception and images of community. Absent institutions, state or otherwise, identities are so protean as to be endlessly shifting. State encouragement of national identity formation facilitates collective action and assures political acquiescence. 25 When states dissolve, therefore, it is not just a brute Leviathan that is lost; it is also a focal point of communal identity. In such instability, separatists act as political entrepreneurs, seeking to promote new notions of identity as alternatives to the state’s official version of nationalism while building new organs of political control.

The topic of separatism rests astride multiple disciplinary, theoretical, and analytical seams.26 Comparative politics and comparative sociology tend to favor an inside-out approach, looking at separatist conflicts as the product of domestic or internal political cleavages and tensions. International relations tends to favor an outside-in approach, looking at separatist pressures as a response to incentives and opportunities provided by the international community. Both of these approaches are nomothetic in orientation, seeking to develop and test broad generic theories about the origins of separatism and its impact in

as a wide a population of cases as possible. A third approach, associated with comparative historical analysis and historical institutionalism, is less interested in generalization than in attending to unique and historically contingent features of individual cases. If separatism is about the political disintegration of state institutions, then its course is deeply constrained by particular historical experiences of political incorporation. Separatism is thus the analytical mirror image of state formation.

Inside-Out Approaches. For a long time the primary thinking about separatism was that it amounted to an internal challenger to statehood. Weber’s equation of statehood with the monopoly of force has long stood as maximal ideal-type, not a reality. Some states come closer to achieving it than others.27 Moreover, states rarely get to impose their notions of national identity without a fight. Ethnic conflict, disputes about communal identity, and disagreement about the distribution of power among groups spur people to resist that state. But grievances alone are not sufficient to cause rebellion. Rebellions are dangerous and their rewards uncertain. Any effort at rebellion must overcome the prohibitive inertia of the collective action problem, in which some people sacrifice but all reap rewards.28

Instrumentalist analyses focus on factors that lower the cost and increase the gain from rebellion. James Fearon and David Laitin, among many others, stress the ecological and geographical determinants of rebellion. Mountains, jungles, and other difficult-to-patrol terrains offer rebels succor and bases for operation. Where and when states are weak, rebels advance.29 Access to natural resources, like diamonds, oil, or other kinds of loot, provide crucial incentives to rebel foot soldiers and leaders alike, raising the benefits of rebellion.30 When they have the opportunity, rebels build more robust infrastructure of governance, including police forces, courts, schools, and welfare programs, in effect supplanting the dysfunctional state and becoming proto-states.31

Separatism is a distinct form of rebellion and has specific etiological characteristics. Rather than overturn a specific regime, separatists want to break a state’s hold over particular territories. Separatist leaders make strategic choices about how and when they claim specific territories, as Harris Mylonas and Nadav Shelef discuss.32 They are engaged in a particular kind of demographic and physical engineering. They try to ensure that their group constitutes a majority (or at least plurality) within its claimed territory.33 The availability of oil or other natural resources in that territory is also important. Access to rent-generating facilities can help rebels overcome collective action problems in recruitment.34 Moreover, the presence of natural resources in what is considered a group’s historical homeland can become grist for grievances. While the central government hordes resources, it denies residents opportunities for political and economic advancement.35 Beyond fighting the titular state, as Kathleen Cunningham

and others argue, separatists also contend with other rival rebel organizations. Building cohesion around the cause of separatism, either by defeating or agglomerating other armed groups, is a key for success.36 For this reason, separatist rebels are typically the most eager to set up parallel state institutions that can monopolize coercive control.37

Outside-In Approaches. International relations scholarship has only recently engaged with the topic of separatism. This line of inquiry has yielded important insights about how separatists respond to the constraints and incentives provided by the global balance of power and the norms and practices surrounding sovereignty. Sovereignty and statehood are adductive. Sovereignty, according to K. J. Holsti, “helps create states; it helps maintain their integrity when under threat from within or without; and it helps guarantee their continuation and prevents their death.”38 At a minimum, separatists pose a challenge to a state’s domestic or empirical sovereignty, the ability to exercise de facto control on the ground. Full-blown secessionists challenge the state’s juridical (de jure) sovereignty, its standing as a member of the society of states, as well. From this outside-in perspective, then, the international community’s support or opposition to separatism is crucial.39 Outside states determine their orientation toward separatists based on their material interests and their normative commitments.40 Reyko Huang and Bridget Coggins show how separatists, in turn, appeal to the international community on both geostrategic and moral grounds.41 Military and economic aid helps separatists effect their own de facto sovereignty. Diplomatic support, up to and including formal recognition of sovereignty and independence, provides crucial juridical support. Incumbent states, for their part, try their best to deny rebels such material and moral resources.42

For much of the twentieth century, global norms of sovereignty formed an important bulwark against separatism. Robert Jackson argues that the international community’s emphasis on de jure sovereignty effectively made territories inviolable and borders immutable. Cold War geopolitics reinforced this general deterrent toward separatism. Efforts to break the borders of one state might spill over to others, creating a slippery slope for state dismemberment and general disorder.43 Pierre Englebert, straddling the comparative-international relations divide, argues that international recognition provided regimes a crucial symbolic resource to regimes and dampened the hopes of any group that might seek separation.44 Since the end of the Cold War, though, this obstacle appears to have lessened. New norms of humanitarian intervention seem to dovetail with claims for self-determination by oppressed minorities.45 The geopolitical alignment no longer precludes external actors from backing separatists, as the United States did in Kosovo and Russia in South Ossetia.

Longitudinal Approaches. Drawn from the tradition of comparative historical analysis, longitudinal approaches to separatism move away from general theory

and toward more specific explanations grounded in particular times and places.46 In their seminal studies of the drivers of state formation in Europe, Charles Tilly, Hendrik Spruyt, and Thomas Ertman each emphasize distinct path-dependent dynamics. Early movers had unique advantages in a highly competitive landscape. Polities that managed to achieve military, economic, and bureaucratic competence were able to survive to take their place in the modern international system. The continual need to assert themselves militarily, fiscally, and administratively became self-reinforcing, leading to ever more robust states. Polities that couldn’t compete effectively, like the Duchy of Burgundy or the Kingdom of Aragon, were dismembered, absorbed, and typically forgotten.47 These dynamics do not translate directly to the developing world, but the vocabulary of path dependence suggests ways to approach separatism as a temporally and historically variant but bounded phenomenon.48

In particular, the breakup of the USSR and Yugoslavia prompted a consideration of the historical processes of segmentation and sedimentation within states affected by the trajectories of separatism. The USSR, as Yuri Slezkine put it, was not a unitary state but a communal apartment, a series of stratified autonomous republics and regions.49 Ostensibly, the ethno-federalist arrangement was supposed to mollify demands for self-determination while fostering cohesion under state socialism. In reality, these territorially segmented units became the perches for separatism when the central state faltered. When the USSR buckled, those groups already enjoying control over autonomous institutions had the best chance to seek independence.50 There was an additional external support to such transition from segmentation to separatism. The international community generally abhorred altering international borders. By retaining the pre-existing territorial demarcation, though, separatist movements were able to show they posed less of a threat to global order. Moreover, parent states were likely to accept secession by higher-order administrative units in order to forestall the more disruptive departure of lower-level ones.51

In addition to contemporaneous segmentation, processes of sedimentation within state institutions also proved to have a significant impact on separatism. Michael Hechter shows how losing autonomy or statehood is a major motivator for ethnic resentment and grievances. Rebellion becomes more likely when the strength of the central governing authority wanes and the original bargain between center and periphery no longer holds.52 Examining the wave of separatist and secessionist bids that emerged in the 1990s and 2000s, numerous crossnational statistical studies found that those groups making separatist and secessionist bids in the 1990s and 2000s and had engaged in failed rebellions and resistance in the late nineteenth century and earlier in the twentieth.53 The pockmarked ethno-federalist structure of the USSR was not a product of overarching design but an improvised attempt to incorporate ethnic groups that had long

resisted Russian domination. When the Romanov empire crumbled in 1917, many of these groups tried to launch their own independent states. The Soviets offered autonomy in the hopes of appeasing the earliest and most potent potential resisters. As the Soviets reconsolidated power, though, they were less accommodating. They used violence to suppress opposition and unilaterally revoked or diluted previous autonomy provisions.54 Just like ethno-territorial segmentation, the sedimented history of failed state building can have path-dependent effects. The experience of having once enjoyed self-governance granted groups the institutional structures necessary to undertake rebellion; the revocation of that autonomy gave them motivation to break away. Such experiences counteract the integrative efforts of state building and provide a catalyst to separation.

Still, the mechanism behind what Philip Roeder calls the “conquered state syndrome,” the propensity of separatism to arise among groups that had lost autonomy, remains obscure.55 Rebel groups can take a multitude of forms and make a variety of claims about identity. Why would separatists seek to resurrect old, seemingly defunct, notions of political community instead of creating new—and potentially more attractive and suasive—ones? How does an extinct political order have enduring power to shape the future?56

This book offers two interrelated answers. First, the memories of bygone institutions are seldom lost, even though states do their best to supplant them with new notions of belonging. Thus, once initiated, identities themselves have a propensity for endurance. They can remain entrenched socially and culturally even after their initial impetus has dissolved. Elites and activists instrumentally try to refurbish and retain the memory of these past political institutions as a way to oppose or resist existing state power. As Allan Hoben and Robert Hefner put it, these institutions and identities are “taught and learned, often quite deliberately . . . [and] provide the social categories of discourse that define who is likely to be good and to be trusted, and who is bad and should be hated and feared.”57 When the central state’s authority dissipates, this prior statehood is a natural or default focal point around which to organize collective actions, similar in many ways to the ready-made platform of ethno-federal segmentation. Parliaments and other institutions can be used to govern this recently regained homeland. Flags, anthems, and banners already exist to represent it. Militias can be raised to defend it. All of this helps separatists to accumulate power in conditions where the state is no longer effective and there are multiple groups vying for territorial control.58

Second, making claims to reinstate prior lost states also has important ramifications for separatists’ engagement abroad. Separatist movements face an uphill battle given the international community’s general tendency to preserve existing territorial boundaries. But by claiming to reinstate a political entity that had already existed in modern history and had standing in the international community, they hope to give themselves a head start. They signal their understanding

of the rules of the international system and their right to belong in international society. The existence of prior statehood can also help in delimiting borders and territory of a future state, further mitigating potential disturbance to the global order. This ultimately increases the chance of gaining external support, up to and including de jure recognition of sovereignty.

Separatism and MENA’s “Missing” States

There has been a great deal of attention to ethnic cleavages and conflicts that divide MENA states, but relatively little to the potentialities of separatism. In the 1970s, leading scholars like Michael Hudson and Iliya Harik wrote about the “horizontal” challenge to Arab states and the difficulty of bringing disparate communities under a single, coherent national identity. Yet they presumed that some form of vertical agglomeration was a foregone conclusion. Harik, following Clifford Geertz’s influential theory of “integrative revolutions,” expected a conglomerate national identity to arise, such as in Lebanon’s confessional system. Hudson foresaw an eventual Gulliverian turn toward pan-Arab regional integration. In both scenarios, political conflict focused on controlling the center, not carving out territories at the periphery.59 Arab states generally did not follow the Soviet example of building segmented ethno-federalist territorial structures to accommodate disparate communities’ demands for self-rule.60

More recent studies of Arab politics emphasize the durability and persistence of states and tend to ignore separatism altogether. Taking an inside-out approach, Sean Yom, Rolf Schwarz, and Thierry Gongora focus on how the political economy of Arab states created its own centripetal power. The arrival of massive oil rents short-circuited the process of state development. With no need to extract taxes or resources from their own population, Arab states did not build durable institutions and national identities. Instead, states took on a kind of armed mediocrity, using rents to bribe their populations into acquiescence or to build ruthless security services to beat down dissent.61 Viewing the region from the outside in, Ian Lustick, Keith Krause, and Boaz Atzili argue that norms of territorial integrity linked to juridical sovereignty and practices of external intervention effectively kept relatively weak and illegitimate Arab states intact. Though they do not deal directly with separatism’s horizontal challenges per se, they agree that ideational and geopolitical factors made changing borders impossible.62 Both the outside-in geopolitical and inside-out political economy approaches point ultimately in the same direction: a collection of states getting a free ride on the rules of sovereignty granted by the international community. They are prone to violence but incapable of—and possibly even disinterested in—asserting effective control over the breadth of their allotted territories or