Acknowledgments

I have made many friends and incurred even more debts in the research and writing of this book. This book grew out of my doctoral work at Cornell University. I thank my graduate committee members—Edward Baptist, Mary Beth Norton, Aaron Sachs, and Shirley Samuels—for their intellectual guidance and support at that early stage, as well as professors Derek Chang, Jefferson Cowie, and Suman Seth for their fine instruction. At Cornell, I workshopped early versions of this project with members of a reading group sponsored by the Society for the Humanities and at the History Americas Colloquium, the Graduate History Colloquium, and the Global Nineteenth Century Graduate Conference. I also must acknowledge the support of the dedicated staff at Olin Library and praise the 2CUL sharing program that permitted me access to Butler Library at Columbia University. This book benefited from critical funding from numerous institutions. From Cornell, I received support in the form of the Henry W. Sage Fellowship, the Joel and Rosemary Silbey Fellowship, the Graduate School Research Travel Grant, the Walter and Sandra LaFeber Research Travel Grant, the Ihlder Research Fellowship, the Paul W. Gates Research Fellowship, the American Studies Program Graduate Research Grant, the Mary Donlon Alger Fellowship, and the Graduate Student Public Humanities Fellowship from the Society for the Humanities. From Eastern Connecticut State University, I received both the Faculty Research Grant from the Connecticut State University American Association of University Professors and the John Fox Slater Research Fund. These funds permitted research travel to archives and the purchase of microfilm collections that proved valuable to the project. From Eastern Connecticut State University, I also obtained reassigned time for research, travel funds to attend multiple conferences, and professional development support. A special thank you to Dr. Stacey Close, Vice President

Acknowledgments

for Equity and Diversity, whose assistance supported the inclusion of several illustrations in this book.In addition, I thank the institutions that have provided me with research travel funds: the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania for providing housing during my research in Philadelphia, the Virginia Historical Society for awarding me its Mellon Research Fellowship, the Newberry Library for granting me status as a Scholar-in-Residence, and LancasterHistory.org for offering me a research fellowship through the National Endowment for the Humanities.

My project benefited from the assistance of librarians and staffers at a great number of federal and state institutions, historical societies, and libraries. I thank especially the devoted staffers at the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; the careful stewards of the Buchanan Papers at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Connie King at the Library Company of Philadelphia; Heather Tennies, Patrick Clarke, and the knowledgeable staff at LancasterHistory.org; Jim Gerencser at the Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College; Nancy Dupree, Norwood Kerr, and the unfailingly polite staff of the Alabama Department of Archives and History; the helpful research staffers at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University; the always cheerful staff at the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina; Jenna Sabre and Alexandra Bainbridge at the Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University; Cheryl Custer at the Fendrick Library, Mercersburg, Pennsylvania; Mike Lear at the Archives and Special Collections, Franklin & Marshall College; and Mazie Bowen at the Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Georgia. Special thanks also are due to the hard-working and dedicated staff at the J. Eugene Smith Library, Eastern Connecticut State University.

Historians of James Buchanan and William Rufus King are few in number, but they lack nothing in the way of enthusiasm for their research subjects. I particularly thank Michael Connolly for his interest in this project at an early stage; John Quist, Michael Birkner, Randall Miller, Thomas Horrocks, Michael Landis, and Joshua Lynn for engaging conversations about Old Buck; Pastor Ron Martin-Minnich, Upper West Conococheague Presbyterian Church, Mercersburg, for hunting down elusive church records; and Daniel Fate Brooks for sharing his passion for William Rufus King. Other historians and stewards of all things Buchanan and King deserve attention, too. Thanks to Doug Smith of Mercersburg Academy for sharing Harriet Lane Johnston materials, Nick Yakas of Phoenix Lodge No. 8, Fayetteville, North Carolina, for confirming King’s Masonic information, and Bland Simpson at the

University of North Carolina for arranging access to the portrait of William Rufus King that graces the cover of this book.

I also thank the professional organizations and societies that have provided venues for my work. These include the American Historical Association, the New York Metro American Studies Association, the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic, the Organization of American Historians, the Association of British American Nineteenth Century Historians, LancasterHistory.org, the Early American Republic Working Group at the City University of New York, the Faculty Scholars Forum at Eastern Connecticut State University, the New England Historical Association, and the Pennsylvania Historical Association. For their valuable advice and camaraderie at various stages of this project, I thank Kelly Brennan Arehart, Diane Barnes, John Belohlavek, Mark Boonshoft, Robyn Davis, David Doyle, Douglas Egerton, Thomas Foster, Joanne Freeman, Craig Friend, Richard Godbeer, Amy Greenberg, Jessica Linker, Jake Lundberg, Stacey Robertson, Rachel Shelden, Manisha Sinha, Frank Towers, Elissa Wade, and Timothy Williams. To my colleagues in the History Department at Eastern Connecticut State University— Caitlin Carenen, Bradley Davis, David Frye, Stefan Kamola, Anna Kirchmann, Joan Meznar, Scott Moore, Jamel Ostwald, and especially Barbara Tucker—thank you.

Several people provided careful readings of individual chapters of this book. I thank the wonderfully generous Barbara Tucker for her first read of early chapter drafts. I also acknowledge the outstanding work of undergraduate research assistants who helped with the preparation of this book: Sara Dean, Joshua Turner, Katerina Mazzacane, Jordan Butler, Uriya Simeon, and Allen Horn. At Oxford University Press, I have benefited from the guidance of my editor, Susan Ferber. Three excellent readers’ reports from Mark Summers, Michael Birkner, and Nicholas Syrett substantially improved this book. Thank you also to the Oxford University Press production team, especially Jeremy Toynbee, for its dedication in bringing this book into print. Finally, a portion of chapter 3, which appeared as “The Bachelor’s Mess: James Buchanan and the Domestic Politics of Doughfacery in Jacksonian America” in The Worlds of James Buchanan and Thaddeus Stevens: Place, Personality, and Politics in the Civil War Era, edited by Michael J. Birkner, John W. Quist, and Randall M. Miller (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2019), is reproduced here with permission.

I have shared my journey into the friendship of James Buchanan and William Rufus King with many friends of my own. In addition to the colleagues noted above, I want to thank my academic friends, especially Alex

Acknowledgments x

Black, Jillian Spivey Caddell, Mark Deets, Brigitte Fielder, Shyla Foster, Rae Grabowski, Amy Kohout, Henry Maar, Daegan Miller, Jacqueline Reynoso, Mark Rice, Stephen Sanfilippo, Jonathan Senchyne, Kathleen Volk, and Xine Yao. Other friends listened patiently to me talk about my project and played host to me during research visits—thanks to Samuel Aronson and George Cooper, William Cammuso, John Carpenter, Jeffrey and Kristin Kayer, Hanny Martinovici, Thomas Ricketts, David Rimshnick, Peter Rimshnick, Zachary Samuels, Preston Shimer, and John Vaughan. Thanks also to mentors and friends John Cebak, Warren Dressler, and David Stuhr.

Finally, my greatest debt is owed to my family. Without the support of my parents, William and Christine Balcerski, I would not have been given the freedom to explore my interests in college and beyond. To siblings Bill, Stephen, and Tracy Balcerski, you now know more about James Buchanan and William Rufus King than nearly anyone else on the planet. I owe also to Dorothy Halperin similar sentiments of gratitude; like my family, she never stopped believing in me and this project. Lastly, to Marc Halperin, I bestow upon you an honorary master’s degree in American history and offer to you the dedication of this book; come what may, I love you.

Introduction

In the aftermath of the Civil War, few wished to remember the politics of the prior generation. Perhaps fewer still wanted to reminisce about the vibrant social landscape of the nation’s capital before the war. To many, such recollections must have recalled a tragic scene from a disastrous era in American history. Fittingly, a historian, Elizabeth Fries Lummis Ellet, took up the challenge of placing the calamities of the war years into a broader story about social elites from days gone by. In her final works Ellet turned to the more recent past, using the papers of prominent women to enliven the people, places, and events of high society. In reviewing the administration of President John Tyler (1841–1845), she ascribed a peculiarly communal aspect. “Members from the various sections of the Union, intending to domesticate with their families for a session, arranged what was styled a ‘mess,’ ” Ellet noted, “generally formed of persons professing the same politics, having an identity of interest, associations, feelings, &c.” Ellet then cited the two most famous messmates from that period, the Democratic senators and lifelong bachelors James Buchanan of Pennsylvania and William Rufus King of Alabama. “Buchanan and King were called ‘the Siamese twins,’ ” she asserted. “They ate, drank, voted and visited together.”1

This intriguing characterization of James Buchanan and William Rufus King as “the Siamese twins” drew upon a phrase that had been evolving for forty years in the American lexicon. It first appeared in 1829, when Scottish promoter Robert Hunter brought the conjoined twins Chang and Eng Bunker—the “Twins from Siam”—to the attention of the American public. During the 1830s, these original Siamese twins became a media sensation, as they toured the United States and England. Soon thereafter, the phrase took

on new, more literary qualities. English writer Edward Bulwer titled an 1833 satirical poem “The Siamese Twins,” while a cartoonist lampooned the “unnatural alliance” of Great Britain and the newly formed nation of Belgium as a conjoined pair. American journalists and cartoonists seized upon the designation in ways that were both more political and gendered. In 1837, for example, a reporter compared the governors of the neighboring states of Mississippi and Arkansas to the “Siamese twins, as they both act and think alike.”2

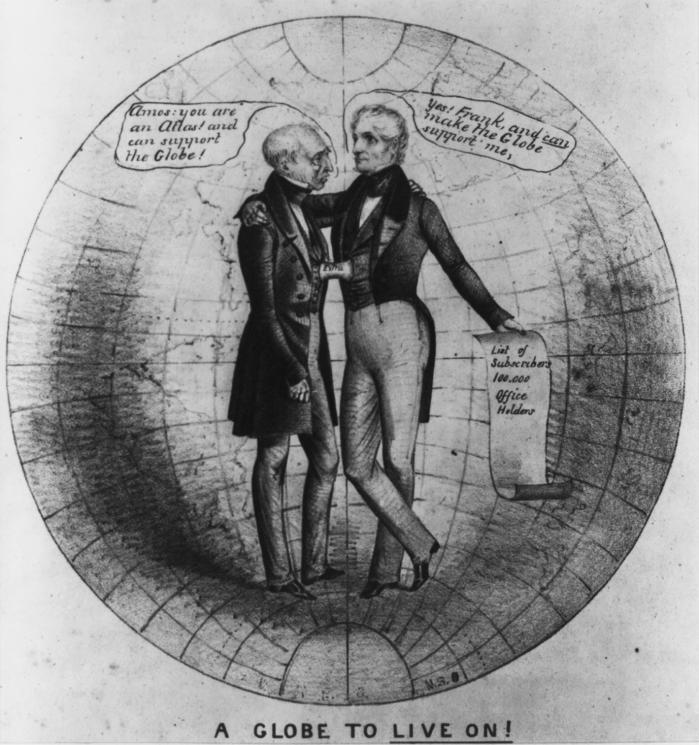

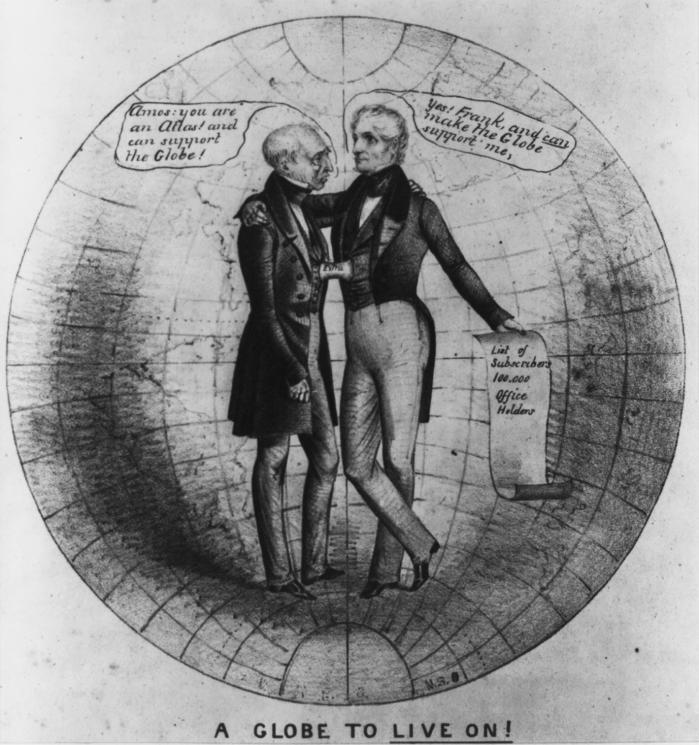

Of all the new meanings attributed to “the Siamese twins,” the political one spread widest and lasted longest. By the 1840s, politicians closely aligned in the public eye were likened, usually in a satirical or pejorative way, to Siamese twins. In the presidential election year of 1840, for example, a Whig cartoonist attacked the partisan and allegedly corrupt connection between Democratic newspaper editors Francis Preston Blair and Amos Kendall by depicting the men conjoined by an oversized ligature at their torsos. In response, a Democratic newspaper editorialized that the Whig presidential candidate William Henry Harrison was a political Siamese twin to his vice presidential running-mate John Tyler. Again in 1844, the duo of John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay warranted the same description. In the heat of the 1856 presidential election, when James Buchanan was a candidate, a pro-Democratic newspaper espoused the connection between the opposition Republican Party and northern abolitionists to be “like Eng and Chang . . . the death of one would kill the other.” Eight years later, Republicans caricatured the Democratic presidential ticket of Civil War general George McClellan of New Jersey and George Pendleton of Ohio as a conjoined pair, bound by a farcical ligature on which read the words “the party tie.”3

Like these other metaphorical couplings, Ellet’s pairing of Buchanan and King certainly warranted the nickname. Even so, this curious label prompts many questions. Who were these two men from the nineteenth-century past? How and why did they enter politics? Why did neither one ever marry, and how unusual were they for not doing so? From there, questions about their “mess” relationship follow. What exactly was the nature of their domestic arrangement in Washington? Did it include a sexual element, or was it merely a platonic friendship? Did eating, drinking, and socializing together really translate to voting together on political issues? Since the phrase “Siamese twins” typically stemmed from a partisan critique, questions about their public personae ensue. What did their political opponents think of them, and what did they write about them in turn? And how did they manage to achieve their political successes in spite of it all? Finally, how did the historian

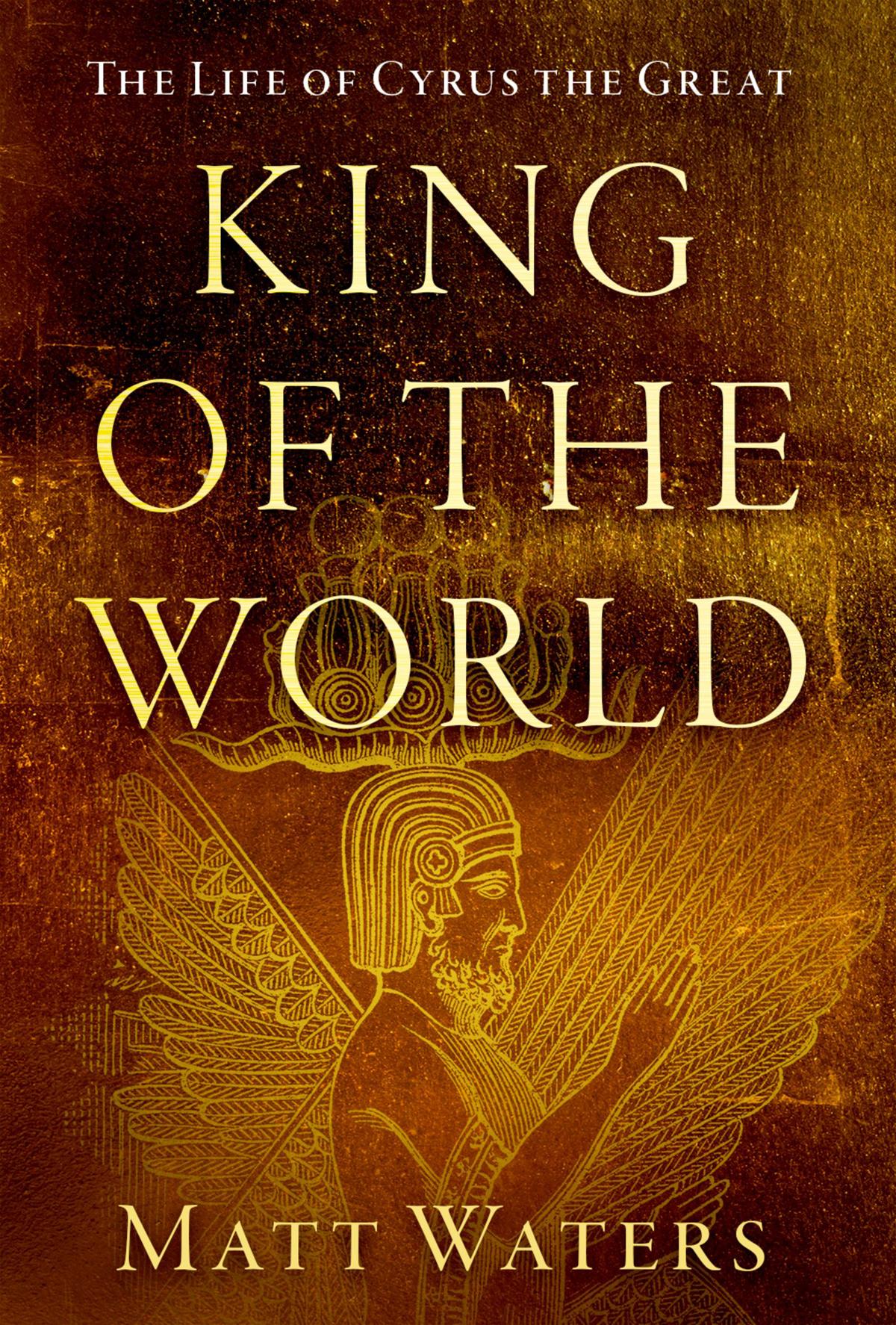

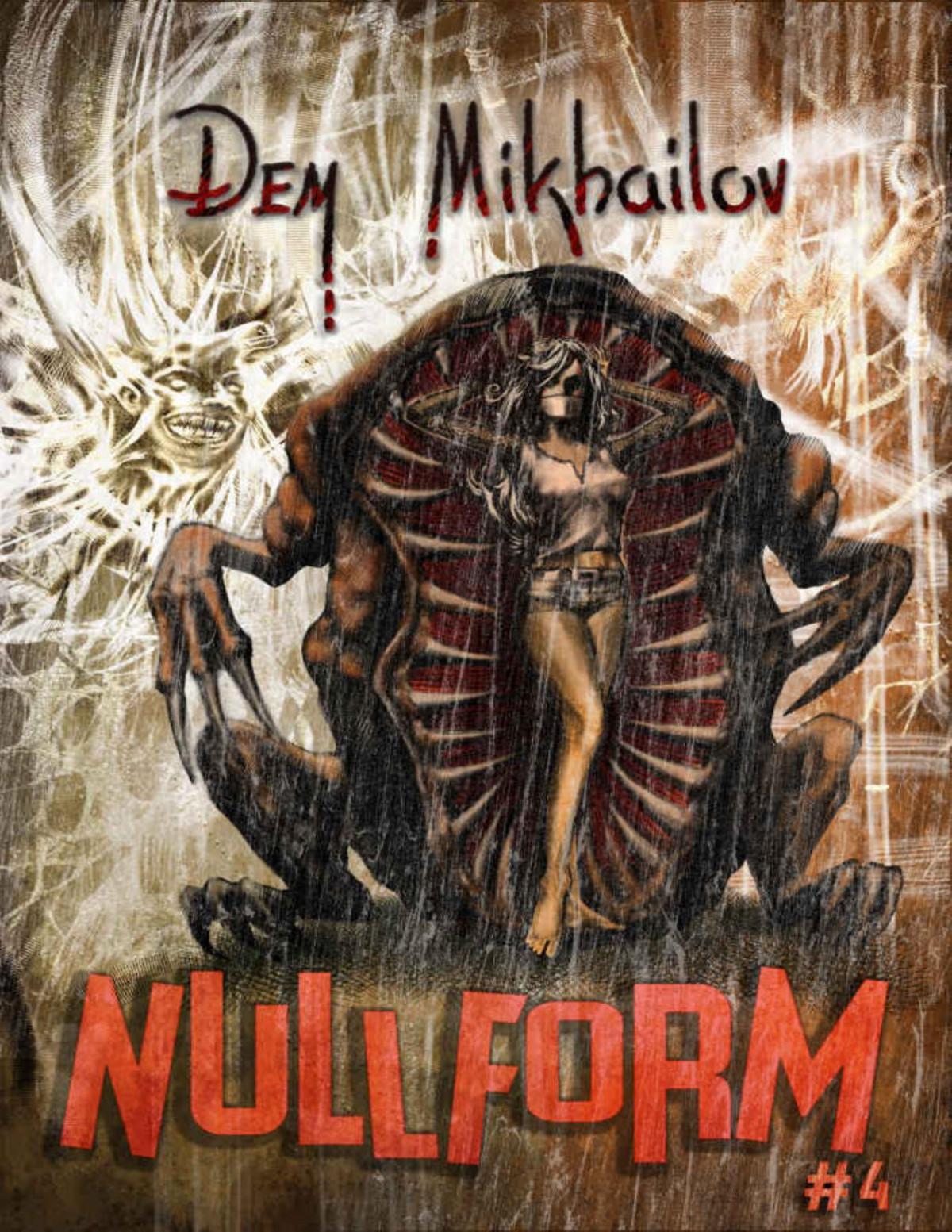

Figure I.1 “A Globe to Live On!” Francis Preston Blair (pictured on the left) says: “Amos: you are an Atlas! and can support the Globe,” to which Amos Kendall, holding a list that reads “List of Subscribers 100,000 Office Holders,” replies, “Yes! Frank, and can make the Globe support me.” Lithograph. Washington, DC: Printed and published by Henry R. Robinson, 1840. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-21235.

Elizabeth Ellet come to remember them as the Siamese twins, and, more to the point, how have they been remembered since?

* * *

The older of the pair by five years, William Rufus DeVane King (1786–1853) was born on the eve of the US Constitutional convention and died as the nation’s sitting vice president. After attending the University of North Carolina, he

rapidly thrived in public life. Elected to the state House of Commons in 1808, he was chosen for the US House of Representatives in 1811, one of the youngest men ever to serve in that body. A fierce War Hawk during the War of 1812, he subsequently served abroad as secretary to the foreign legation in the Kingdom of Naples and then at St. Petersburg, Russia. Upon his return to America, King headed southwest as part of the great cotton boom and settled near the new town of Selma, Alabama. Elected to the US Senate in 1819, he served continuously until President Tyler appointed him American minister to France in 1844. By the time of his first mess arrangement with Buchanan, begun a decade earlier, he was firmly established as both a confirmed bachelor and a southern spokesman for national unity in the Democratic Party.4

By comparison, James Buchanan (1791–1868) was born during the administration of President George Washington and died publicly discredited during his own postpresidential retreat to Wheatland, his country estate near Lancaster. In his education at Dickinson College, legal training, and early political engagements, he shared a trajectory similar to King’s. As a Pennsylvania Federalist and state legislator, however, he opposed the War of 1812 and received the warm support of his Lancaster townsmen for the stance. His failed engagement to Ann Coleman ended tragically with her death in 1819, after which time he recommitted himself to a life in politics. Elected to the US House of Representatives soon thereafter, he served five terms in that body. Next exiled to Russia by President Andrew Jackson, he returned triumphantly in 1833, with a successfully negotiated commercial treaty in hand. At the time of his election to the US Senate in 1834, he was the leader of the Amalgamator wing of the Pennsylvania Democratic Party and a rising star on the national scene. Like King, he was a bachelor, though a far more reluctant one, and a northern voice for compromise and conciliation within the Democratic Party.5

The period of their active friendship, from their initial mess arrangement in December 1834 to King’s death in April 1853, spanned more than eighteen years. Within this timeline, their relationship contained two discrete phases: first, the period from December 1834 to May 1844, when they overlapped in the US Senate and often lived together while in Washington; and second, the period from May 1844 to April 1853, when, with a few notable exceptions, the two men lived apart and operated independently. In its initial phase, their friendship centered around the institution of the Washington boardinghouse, or mess, where they ate and drank together in relative domestic harmony. They also attended social functions together, which often centered around still more eating and drinking. By thus intertwining their

domestic fortunes while in Washington, they slowly but steadily forged an intimate personal friendship. In time, Buchanan and King intermingled members of their own families, notably their two nieces Harriet Rebecca Lane and Catherine Margaret Ellis, into an extended network of affective kinship. During this first, more intimate phase of their friendship, they became one of the best-known and most successful examples of a domestic political partnership in American history.6

In many ways, the structure of congressional service in the early American republic dictated the first phase of their friendship (1834–1844). Even after Congress relocated from Philadelphia to the unfinished city of Washington, DC, at the close of 1800, the average congressman spent surprisingly little time in the capital. Congressional sessions, divided into two-year spans to match the length of terms for members of the House of Representatives, followed an unusually long cycle from election to service. Many representatives were selected fully a year or more before the start of their terms of office, a situation that did not change officially until 1875. In the case of William Rufus King, for example, he was elected to his seat in the fall of 1810, but did not arrive in Washington as a member of the 12th US Congress until November 1811. From there, the first session of the new Congress most typically lasted until the late spring or early summer months, after which the body recessed until fall (this pattern persisted well into the 1930s). Only then did most congressmen return home, where, as it turns out, the majority had consciously chosen to live apart from their wives and families while in Washington.7

Several factors compounded the decision of most congressmen to separate from loved ones. For one, the great difficulty and slow rate of travel in the era before widespread railroad connections made a trip to Washington an uncertain proposition. At the start of his congressional career, for example, King endured a four- to five-day journey from North Carolina to Washington, while Buchanan’s trip from Lancaster took the better part of two days, with stops in Philadelphia and Baltimore. For another, most lawmakers were not compensated sufficiently to cover the expenses of maintaining both a residence in Washington and another back home. Until 1816, representatives were paid a per diem rate of $6 (unchanged since the first Congress in 1789), after which a salary of $1,500 was set. However, this new allotment proved wildly controversial, and the subsequent Congress was forced to return to the per diem rate system, with a twist—representatives and senators were granted an $8 per diem and another $8 per twenty miles traveled to Washington. The convoluted pay scheme lasted until 1855, with one result being that even congressional sessions without much business lasted the full time allotted. If the

paltry salary were not enough to turn away elected officials from serving multiple terms, many congressional districts practiced a strict system of rotation in office, called a “yearling policy” by one historian, such that turnover in office was comparatively much higher in the early nineteenth century than it is today. On top of that, many congressmen withdrew early from their terms in office, often motivated by entirely personal factors. Washington could be a lonely place.8

The living conditions of early Washington also drove the parameters of social life in the capital and thus the early years of the friendship of Buchanan and King. Far from the modern city that it later became, the capital in these years was very much a work in progress. The roads were muddy and the surrounding landscape dotted with swamps. Even if a congressman could afford to bring his family to Washington, accommodations were often communal and cramped. Few politicians, save members of the cabinet, ever owned their own homes. To solve the problem of housing, congressmen lived together in boardinghouses, which were called by the name “mess.” From the earliest Congresses of the 1790s until after the Civil War, these boardinghouses most commonly accommodated congressmen while in Washington. For the reasonable rate of around ten dollars a week, individuals could obtain single rooms within a shared house that might contain as many as a dozen other bedrooms, each often furnished with little more than a bed, dresser, and nightstand. In the era before indoor plumbing, the boarders relied on domestic servants, often enslaved African Americans, to meet the everyday needs of ablution. Although boardinghouses existed in every American city during these years, the Washington boardinghouse differed in that its inhabitants were the country’s leading elected officials.9

There was an essential communal element to boardinghouse life in the capital. Dinner, the most important of the meals, was served between three and six o’clock, with a menu that featured an assortment of meats, fish, berries, and pies. Alcoholic beverages such as wine, brandy, and madeira often accompanied meals, though congressmen provided these items at their own expense. The messmates regularly congregated in the shared parlors, especially around the fireplaces in the colder months, where they smoked cigars and discussed politics and the social doings of the capital. Since many boardinghouses featured the mixed company of men and women, such gatherings could be quite formal. From these parlors, calls were made and returned around the Capitol Hill neighborhood, such that congressional messes functioned as social centers in the early republic. Congressmen frequently entertained their fellow politicians with food and drink, just as they

might have hosted guests back home. And without access to formal offices— congressmen worked primarily from their desks in the chambers of the Capitol—boardinghouses functioned as auxiliary office space as well. From these “parlor politics,” much important legislation germinated.10

On the one hand, the basis for the relationship of James Buchanan and William Rufus King was not particularly uncommon. Whether as cause or effect of their boardinghouse connection, Buchanan and King followed a remarkably similar political course as congressional messmates. As Elizabeth Ellet noted, they almost always voted in common with one another. Stalwart Jacksonians, they offered unwavering support for the Democratic agenda, including the independent subtreasury system, a compromise tariff, and the expansion of federal land-holdings. But each man counseled careful moderation on sectional issues. For his part, King consistently balanced the interests of the slaveholding South with those of the national Democratic Party; however, his political partnership with the patriotic Buchanan required that he prioritize the permanent continuation of the Union. In turn, Buchanan joined King in combating abolitionism; he even devised a key aspect of the Senate’s infamous gag rule that forbade the reception of anti-slavery petitions. Along with their Democratic messmates, Buchanan and King constituted a powerful voting bloc in the Jacksonian era. By the end of their shared mess, they agreed implicitly that the principles of their increasingly conservative creed offered the best way to preserve the national Union.11

On the other hand, their nearly ten-year boardinghouse relationship appears quite unusual in retrospect. After all, the two men originally hailed from very different parts of the country (King from the South, Buchanan from the mid-Atlantic), from varying socioeconomic statuses (King, a scion of wealthy slaveholding planters; Buchanan, the son of a yeoman shopkeeper on the western frontier), and opposite political parties (King an adherent to the Democratic-Republican Party, Buchanan a devoted Federalist). They nevertheless shared a few essential personal factors in common. Being descendants of Scots-Irish immigrants, both men shared similar ethno-cultural origins. They also attended college in an age when higher education was a luxury. Most critically, neither man married. In their capacities as lifelong bachelors, they forged an enduring political partnership that withstood the many challenges of their public lives.

In the second phase of their relationship (1844–1853), separated by distance, their friendship lost something of its earlier personal intimacy and devolved into a more overtly political alliance. While King served as American minister to France, Buchanan transitioned from the senate to

the cabinet as secretary of state under President James Knox Polk. Thus separated, the inherent weaknesses of their friendship forged by domestic propinquity—witnessed in the scattered nature of their correspondence and the widening gulf between their romantic pursuits—became painfully evident. Even as King’s counsel proved personally beneficial to Buchanan at critical moments, they drifted apart politically, especially over foreign policy questions. Under the expansionist Polk, Buchanan promoted territorial conquest, from Mexico to Cuba, for the benefit of southern slaveholders; ironically, King advised against the acquisition of these same lands. In their final years, they approached political questions at cross-purposes. During the congressional debates of 1850, Buchanan attempted to remain above the political fray, while King actively worked for a lasting compromise. Even so, glimpses of their old domestic intimacy resurfaced, as Buchanan occasionally visited with King in Washington. But these later-life efforts proved fleeting. In the end, the alienating effects of distance and time, compounded by a subtle divergence in their political views, had reduced the former intimacy of their friendship.

Nevertheless, the symbolic meaning of their political union soared to new heights in its final years. During the second phase of their friendship, each man reached, and nearly obtained together, the nomination of the Democratic Party for the vice presidency (King) and presidency (Buchanan). In the presidential cycles of 1844, 1848, and finally 1852, they worked tirelessly for a combined Buchanan-King ticket, but each time the political tides turned against a “bachelor ticket” in favor of other combinations. All the same, their brand of political conservativism appealed to their fellow partisans, as a safe choice in the face of ever-mounting sectionalism. In 1852, the Democratic Party selected King as its vice presidential nominee to run alongside Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire, while it chose Buchanan as its presidential candidate in 1856. Like the other pairs of political Siamese twins of the era, each man had proven integral to the success of the other. Yet conjoined as they were, their individual identities had been merged before the councils of the national Democratic Party. In consequence, only one of the two men seemed capable of political advancement at a time.

The active lifespan of these Siamese twins thus spanned from the partisan years of the Jacksonian era to the more sectional ones of the late antebellum period. During those same eighteen years, the United States expanded from a nation circumscribed by rivers for its western border to one bounded by oceans; grew its population, both free and enslaved, at unprecedented rates; and finally deadlocked its politics over the divisive issue of slavery. Indeed, at

the heart of the friendship of Buchanan and King lay a solemn pact, developed in the boardinghouses of Jacksonian Washington, that the Union must not split over the question of slavery. As a politically conservative northerner, Buchanan acquiesced to protect southern interests at almost any price, while as a politically moderate southerner, King stemmed the tide of radical sectionalism in favor of compromise. As such, they comprised a cross-sectional, conservative force in American politics for nearly a generation. Theirs was an interwoven, intertwined, and finally interdependent union that worked primarily to better one another, the Democratic Party, and, by extension, the nation as they conceived it. This book tells their story.

The duo of Buchanan and King received much criticism, often rendered in the form of gossip, from their opponents. This gossip can be understood as gendered language in the “grammar of political combat.” For some adversaries, character attacks allowed for the easy dismissal of political rivals, such as when Andrew Jackson supposedly called King by the name “Miss Nancy” in the 1830s or when John Quincy Adams recorded in his diary that King was “a gentle slave-monger” in 1844. For others, colorful insults levied against opponents endeared them to their correspondents, such as when Aaron Brown of Tennessee variously ridiculed King as “Aunt Nancy,” “Miss Fancy,” and Buchanan’s “wife” in an 1844 letter to Sarah Childress Polk, wife of the future president. In turn, King and Buchanan gossiped among themselves, and with various female family members and friends, in the refined diction of highly educated men. In so doing, they established their own “grammar of manhood,” in which the exigencies of a political agenda intersected with the private realm of thought and feeling. Gossip thus circulated across the private correspondence of multiple circles of male and female political actors.12

While their political adversaries could only speculate about the relationship of Buchanan and King, the scholarship of subsequent generations has uncovered far more evidence about the pair. In the 1880s George Ticknor Curtis published the first major biography of James Buchanan, which included a now infamous letter from Buchanan to Mrs. Cornelia Roosevelt, dated May 13, 1844. “I am now ‘solitary and alone,’ having no companion in the house with me,” he complained following King’s departure from Washington. “I have gone a wooing to several gentlemen, but have not succeeded with any one of them,” he reported, before adding: “I feel that it is not good for man to be alone; and should not be astonished to find myself married to some old

maid who can nurse me when I am sick, provide good dinners for me when I am well, & not expect from me any very ardent or romantic affection.” In the early 1900s John Bassett Moore, editor of the largest collection of Buchanan letters and papers, reprinted this letter and several others from the BuchananKing correspondence, though he offered little context for them. This new evidence notwithstanding, neither Curtis nor Moore replicated the characterization of Buchanan and King as Siamese twins.13

Matters began to change with the next generation of Buchanan biographers. In an article from 1938, biographer Philip Auchampaugh, likely drawing on the reference provided by Elizabeth Ellet, included a footnote that described King as “Buchanan’s ‘Siamese Twin,’ United States Senator for Alabama.” In 1962, Philip Klein published the definitive biography of Buchanan. About Buchanan’s relationship with King, however, Klein largely repeated the chatter of previous generations: “Washington had begun to refer to [King] and Buchanan as ‘the Siamese twins.’ ” While Buchanan’s major biographers quietly elided this gossip, the Polk biographer Charles Sellers expanded upon it. King’s “conspicuous intimacy with the bachelor Buchanan,” he wrote in 1966, “gave rise to some cruel jibes around Washington.” Sellers then repeated the salient gossip of Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and Aaron Brown, and, in a footnote, excerpted King’s reply to Buchanan’s May 1844 letter. “I am selfish enough to hope you will not be able to procure an associate, who will cause you to feel no regret at our separation. For myself, I shall feel lonely in the midst of Paris, for there I shall have no Friends with whom I can commune as with my own thoughts.” The pieces of a new interpretation were gradually falling into place.14

Nevertheless, the intimate nature of male friendships little concerned the narratives constructed by older forms of political history. Indeed, the relationship of Buchanan and King may well have remained a footnote to American history, had it not been for a new interest in the study of historical gender and sexuality, especially same-sex sexuality, in the past several decades. In turn, the popular view of Buchanan’s various intimate attachments, and especially his relationship with King, began to change radically beginning in the 1980s. Tabloid journalism played a critical role in the transformation. On the front cover of its November 1987 issue, for example, Penthouse Magazine pronounced: “Our First Gay President, Out of the Closet, Finally.” In the linked article, New York gossip columnist Sharon Churcher pointed to a forthcoming book by historian Carl Anthony as evidence for the assertion. But even before the publication of Anthony’s First Ladies (1990), Churcher’s sensational article attracted the notice of journalist Shelley Ross, who opined

in her own book about presidential sex scandals: “Perhaps Buchanan’s dark secret was that he was a homosexual, a notion that has crept through historical literature for decades.” For his part, Anthony, who drew heavily upon both Klein and Sellers, concluded: “Whatever manifestations it might have taken, Buchanan maintained a longtime relationship with King.”15

Once the question of the nature of Buchanan’s relationship with King had been raised, more imaginative answers became inevitable. Although he had pledged in his play Buchanan Dying (1974) that he would not publish any more about Buchanan, writer John Updike returned to his fellow Lancastrian in his novel Memories of the Ford Administration (1992). He detailed the mess life shared by Buchanan and King, surmising at one point that the pair enjoyed “the leathery, cluttered, cozy, tobacco-scented bachelor quarters where, emerging from separate bedrooms and returning from divided duties, they often shared morning bacon and evening claret.” Updike variously labeled King a “beau ideal” and “a love object” of Buchanan’s, but he ultimately found “little” in the way of “traces of homosexual passion.” Buchanan, he concluded, looked to King as an “older brother.” Many academic historians embraced the Updike reading, with one critic calling it the “best thing that has happened to James Buchanan since 1856.”16

Regardless, Updike’s relatively circumspect characterization of their relationship has not stopped a veritable torrent of speculation about the pair. For the most part, these surmises have addressed the question of each man’s sexual orientation. Typical of these new interpretations are the views of one historian who equivocated that Buchanan and King “were likely gay,” or that of another who asserted more forcefully, “I’m sure that Buchanan was gay.” Still, even these scholars have based their arguments, however flawed, in the historical record. By contrast, the Internet has enabled an explosion in gossip, misinformation, and erotic imagination about Buchanan and King, with only the slightest basis in evidence. At the start of the twenty-first century, it has become practically de rigueur in many popular circles to call King and Buchanan America’s first gay vice president and president, respectively.17

At the heart of this new understanding lay a growing interest in discovering and assessing the sexual orientation of figures from the American past. The search for a usable queer past, begun in earnest during the 1970s, has widened in scope and scale and evolved into the academic study of LGBT history. The difficulty of locating, with certainty, examples of same-sex behavior—to say nothing of identities and orientations—in the early American past has defined a major methodological problem of the field of LGBT history. Accordingly, how one conceives and describes same-sex attractions and relationships has

provoked a debate between those taking an “essentialist” view, who believe that same-sex attractions, behaviors, and identities as lived today similarly existed in past eras, versus those who take a “social constructionist” view that the same require attention to the societal definitions and practices during the period in question. Nevertheless, this ongoing dialogue has generated more careful attention to the nature of historical sources and the possibility of new interpretations.18

In the case of Buchanan and King, an essentialist view of the two men as gay has certainly predominated the popular and scholarly imagination. However, this book finds that the surviving evidence neither supports a definitive assessment of either man’s sexuality, nor the occurrence of a sexual liaison between them. Instead, this book argues that their relationship conformed to an observable pattern of intimate male friendships prevalent in the first half of the nineteenth century. Like many words, the present understanding of “intimacy,” which today primarily connotes a physical closeness, has evolved from its earlier meaning, when it usually conveyed a shared trust on a personal level. For their part, politicians understood their associations with other public men to include two distinct, if overlapping, categories: the first of these, personal or affective friendships, involved a significant level of intimacy, while the second, political or public friendships, functioned more instrumentally to advance common interests. Of course, politicians commonly built relationships with one another that contained elements of both kinds of friendships; as Buchanan himself later wrote, his friendship with King was an “intimate personal & political association” unmatched by any other.19

This conception of intimate male friendship places the relationship of Buchanan and King at the heart of a vital part of the political process and, in so doing, clarifies the possibilities for political partnerships in early America. Borrowing another term from this period, Buchanan and King may be understood as sharing a “bosom friendship,” one suggestive of a particular kind of domestic intimacy common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In the 1750s, Dr. Samuel Johnson noted in his dictionary that bosom friendship included a “communication of secrets.” Later lexicographers also stressed the connection to sharing private thoughts and feelings. For the most part, such “romantic friendships” were the special domain of women. Yet by the middle of the nineteenth century, the American novelist Herman Melville could use the term to describe the symbolic marriage of Queequeg and Ishmael in his chapter titled “A Bosom Friend” from Moby Dick (1851). The special bond of Melville’s sailors, built as it was on the close quarters of the whaling ship, paralleled the similarly confined setting of the Washington boardinghouse.

But unlike the close companionship of Melville’s sailors, politicians often viewed their bosom friendships in more instrumental ways.20

Indeed, friendships among politicians had long been an important way to knit together the disparate strands of democratic societies. Following the American Revolution, historian Richard Godbeer has argued, “Americans turned to friendship as an emotional anchor for the new nation itself as it struggled to establish social and political stability.” In this way, these friendships enabled critical connections otherwise unavailable on the national level, which in turn promoted greater partisan development. Similarly, Ivy Schweitzer noted in her study of friendship that such relationships represented the “privileged and dominant affiliative modes” available to political men, often at the expense of women and enslaved people. As educated elites, politicians modeled the intellectually restrained manhood common among the genteel classes. In their dress, appearance, and manly comportment, they paid careful attention to the cultural norms expected of gentlemen, whether on the dueling grounds or in the halls of Congress. The political culture of the party system, constructed upon the idealized notion of friendship among elites from different cultural, social, and economic backgrounds, thus operated to bind men together.21

By the nineteenth century, the concept of “bosom friends” was already part and parcel of American politics. Less pejorative than “Siamese twins,” the term most often appeared in a positive light—whether as an elegiac for statesmen who had passed away or as a suggestion of personal intimacy among politicians. Upon the death of the old Jeffersonian Nathaniel Macon of North Carolina in 1837, for example, he was noted as the bosom friend of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Andrew Jackson. In the 1840s, Martin Van Buren of New York was tagged as a bosom friend to fellow New Yorker Silas Wright. The same went for the duo of James Polk and Andrew Jackson, both from Tennessee, whose bosom friendship was applauded at the 1844 Democratic nominating convention. Similarly, Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire was called the bosom friend of Alfred Nicholson of Tennessee during the Democratic nominating convention in 1852. As with all political terms, however, the phrase could also be used in less charitable ways. Democratic rivals dismissed the pairing of Buchanan and King as mere bosom friends. As late as 1856, Buchanan and Van Buren were still lumped together as bosom friends, even though they had long since parted political ways.22

The bosom friendship of Buchanan and King represented something new in the political process. As the era of the founders gave way to the leadership of the second generation, the resulting partisanship eventually hardened into