https://ebookmass.com/product/blueprints-psychiatry-6th-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Blueprints Neurology (Blueprints Series) Fifth Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/blueprints-neurology-blueprints-seriesfifth-edition/ ebookmass.com

Case Files Psychiatry 6th Edition Edition Eugene C. Toy

https://ebookmass.com/product/case-files-psychiatry-6th-editionedition-eugene-c-toy/

ebookmass.com

Primary Care Psychiatry 2nd Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/primary-care-psychiatry-2nd-editionebook-pdf/ ebookmass.com

The Game Changer: A San Francisco Rockets Baseball Novel (Hot Streak Series Book 1) Aurora Paige

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-game-changer-a-san-franciscorockets-baseball-novel-hot-streak-series-book-1-aurora-paige-2/ ebookmass.com

Wolf’s Claimed Mate: Wolf Shifter Pretend Romance (Silverlake Valley Wolves Book 3) Sansa Moon

https://ebookmass.com/product/wolfs-claimed-mate-wolf-shifter-pretendromance-silverlake-valley-wolves-book-3-sansa-moon/

ebookmass.com

Death, Dot & Daisy: A Post-Apocalyptic Murder Mystery Goodman

https://ebookmass.com/product/death-dot-daisy-a-post-apocalypticmurder-mystery-goodman/

ebookmass.com

Vilfredo Pareto: An Intellectual Biography, Volume III: From Liberty to Science (1898–1923) Fiorenzo Mornati

https://ebookmass.com/product/vilfredo-pareto-an-intellectualbiography-volume-iii-from-liberty-to-science-1898-1923-fiorenzomornati/

ebookmass.com

The New Suburbia: How Diversity Remade Suburban Life in Los Angeles after 1945 Becky M. Nicolaides

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-new-suburbia-how-diversity-remadesuburban-life-in-los-angeles-after-1945-becky-m-nicolaides/

ebookmass.com

John Donne's Language of Disease Alison Bumke

https://ebookmass.com/product/john-donnes-language-of-disease-alisonbumke/

ebookmass.com

Atlas of Oral Histology 2nd Edition Harikrishnan Prasad

https://ebookmass.com/product/atlas-of-oral-histology-2nd-editionharikrishnan-prasad/

ebookmass.com

Preface

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Contributors

Psychotic Disorders

Bipolar Disorders

Depressive Disorders

Anxiety Disorders

Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders and Dissociative Disorders

Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

Eating Disorders

Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Conditions

Antidepressants

Mood

Anxiolytics

Major

Psychological

Margaret Benningfield, MD

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Ramzi Mardam Bey, MD

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Ronald L. Cowan, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Professor of Radiology and Radiological Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Professor of Psychology

Vanderbilt University

Nashville, Tennessee

Sheryl Fleisch, MD

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Bradley Freeman, MD

Associate Professor of Clinical Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Sonia Matwin, PhD

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Michael J. Murphy, MD, MPH

National Medical Director

Behavioral Health

Hospital Corporation of America

Nashville, Tennessee

Adam Pendleton, MD, MBA

Fellow in Geriatric Psychiatry

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Meghan Riddle, MD

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD

Chief Medical Officer

New York State Office of Mental Health

Adjunct Professor

Columbia/Mailman School of Public Health

Medical Editor for Mental Health

The Huffington Post

Contributing Writer

US News and World Report

New York, New York

Maja Skikic, MD

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Jonathan Smith, MD

Fellow in Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Yasas Chandra Tanguturi, MBChB

Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Jose Arriola Vigo, MD

Fellow in Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Edwin Williamson, MD

Assistant

Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Blueprints Psychiatry was conceived by a group of recent medical school graduates who saw that there was a need for a thorough yet compact review of psychiatry that would adequately prepare students for the USMLE yet would be digestible in small pieces that busy residents can read during rare moments of calm between busy hospital and clinical responsibilities. Many students have reported that the book is also useful for the successful completion of the core and advanced psychiatry clerkships. We believe that the book provides a good overview of the field that the student should supplement with more in-depth reading. Before Blueprints Psychiatry, we felt that review books were either too cursory to be adequate or too detailed in their coverage for busy readers with little free time. We have kept the content current by repeated updates and revisions of the book while retaining a balance between comprehensiveness and brevity. This new edition reflects changes in response to user feedback. The structure of the book mirrors the major concepts and therapeutics of modern psychiatric practice. We cover each major diagnostic category, each major class of somatic and psychotherapeutic treatment, legal issues, and special situations that are unique to the field. In this edition, we have updated all diagnoses to those included in the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition (DSM-5) and have included new images, 25% more USMLE study questions, and a Neural Basis section for each major diagnostic category. We recommend that those preparing for USMLE read the book in

chapter order but cross reference when helpful between diagnostic and treatment chapters. We hope that Blueprints Psychiatry fits as neatly into your study regimen as it fits into your backpack or briefcase. You never know when you’ll have a free moment to review for the boards!

Michael J. Murphy

Ronald L. Cowan

We would like to acknowledge the faculty, staff, medical students, and trainees of the Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital and Vanderbilt University Medical Center for their contributions and ongoing inspiration.

Michael J. Murphy

Ronald L. Cowan

AA Alcoholics anonymous

ABG Arterial blood gas

ACLS Advanced cardiac life support

ADHD Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

ASP Antisocial personality disorder

BAL Blood alcohol level

BID Twice daily

CBC Complete blood count

CBT Cognitive-behavioral therapy

CNS Central nervous system

CO2 Carbon dioxide

CPR Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

CSF Cerebrospinal fluid

CT Computerized tomography

CVA Cerebrovascular accident

DBT Dialectical behavior therapy

DID Dissociative identity disorder

DT Delirium tremens

ECG Electrocardiogram

ECT Electroconvulsive therapy

EEG Electroencephalogram

EPS Extrapyramidal symptoms

EW Emergency ward

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

5HIAA 5-hydroxy indoleacetic acid

5HT 5-hydroxy tryptamine

GABA Gamma-amino butyric acid

GAD Generalized anxiety disorder

GHB Gamma-hydroxybutyrate

GI Gastrointestinal

HIV Human immunodeficiency virus

HPF High-power field

ICU Intensive care unit

IM Intramuscular

IPT Intrapersonal therapy

IQ Intelligence quotient

IV Intravenous

LP Lumbar puncture

LSD Lysergic acid diethylamine

MAOI Monoamine oxidase inhibitor

MCV Mean corpuscular volume

MDMA 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine

MR Mental retardation

MRI Magnetic resonance imaging

NIDA National Institute on Drug Abuse

NMS Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

OCD Obsessive-compulsive disorder

PCA Patient-controlled analgesia

PMN Polymorphonuclear leukocytes

PO By mouth

PTSD Posttraumatic stress disorder

QD Each day

REM Rapid eye movement

SES Socioeconomic status

SSRI Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

TCA Tricyclic antidepressant

TD Tardive dyskinesia

T4 Tetra-iodo thyronine

TID Three times daily

TSH Thyroid-stimulating hormone

T3 Tri-iodo thyronine

WBC White blood cell count

WISC-R Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Revised

Psychotic disorders are a collection of disorders in which psychosis, defined as a gross impairment in reality testing, predominates the symptom complex. Psychotic symptoms are characterized into five domains: hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thought, disorganized or abnormal motor behavior, and negative symptoms. Table 1-1 lists the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5) classification of the psychotic disorders.

TABLE 1-1. Psychotic Disorders

Schizophrenia

Schizophreniform disorder

Schizoaffective disorder

Brief psychotic disorder

Schizotypal (personality) disorder

Delusional disorder

It is important to understand that primary psychotic disorders are different from mood disorders with psychotic features and drug-induced psychosis. Patients can present with a severe episode of depression or mania and have delusions and hallucinations. These patients do not have a primary psychotic disorder; rather, their psychosis is secondary to a mood disorder.

The diagnoses described in this chapter are among the most severely disabling of mental disorders. Disability is due in part to the chronicity and the extreme degree of social and occupational dysfunction associated with these disorders.

NEURAL BASIS

Much of our understanding of the neural basis for psychotic disorders is based in research on schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is currently considered a neurodevelopmental illness. Reduced regional brain volume with enlarged cerebral ventricles is a hallmark finding. Brain volume is reduced in limbic regions including amygdala, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus. The prefrontal cortex microanatomy is altered. Thalamic and basal ganglia regions are also affected. Altered dopamine function is strongly implicated in positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. An excess of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway is thought to contribute to the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, whereas deficient dopamine function in the mesocortical pathways is thought to contribute to the negative symptoms. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, and the other monoamine neurotransmitters are also likely affected.

SCHIZOPHRENIA

Schizophrenia is a disorder in which patients have psychotic symptoms and social or occupational dysfunction that persists for at least 6 months.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Schizophrenia affects 1% of the population. The typical age of

onset is the late teens to the early 20s for men and the mid- to late 20s for women. Women are more likely to have a “first break” later in life; in fact, about one-third of women have an onset of illness after age 30, with a second peak occurring after menopause. Schizophrenia is diagnosed disproportionately among the lower socioeconomic classes; although theories exist for this finding, none has been substantiated.

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for schizophrenia include genetic risk factors (family history), prenatal and perinatal factors such as difficulties or infections during maternal pregnancy or delivery, winter births, neurocognitive abnormalities such as low premorbid intelligence quotient (IQ) or early childhood neurodevelopmental difficulties, urban living, migration to a different culture, sexual trauma, and cannabis use (especially in susceptible individuals).

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of schizophrenia is unknown. There is a clear inheritable component, but familial incidence is sporadic, and schizophrenia does occur in families with no history of the disease. Schizophrenia is widely believed to be a neurodevelopmental disorder. Multiple neuronal types and pathways appear to be implicated, including those using the neurotransmitters dopamine, glutamate, and GABA.

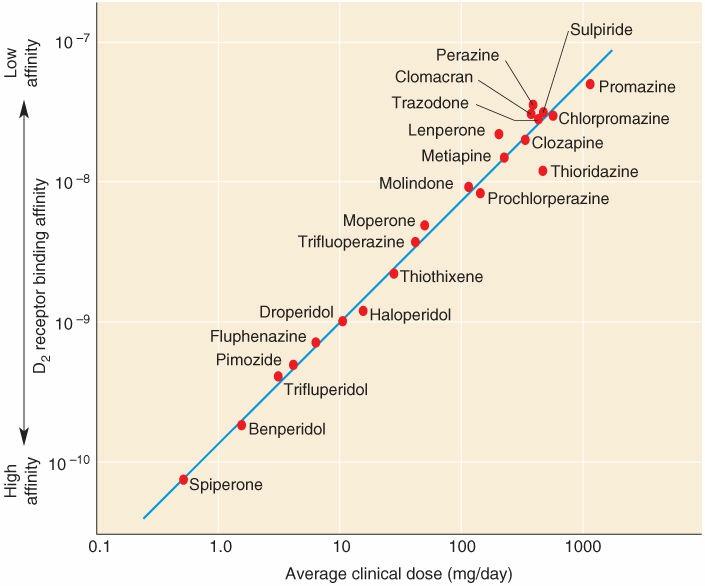

Dopamine

The most widely investigated theory for contributions to schizophrenia is the dopamine hypothesis, which posits that schizophrenia is due to hyperactivity in brain dopaminergic pathways. This theory is consistent with the efficacy of

antipsychotics (which block dopamine receptors) (Fig. 1-1) and the ability of drugs (such as cocaine or amphetamines) that stimulate dopaminergic activity to induce psychosis. Postmortem studies have also shown higher numbers of dopamine receptors in specific subcortical nuclei of those with schizophrenia than in those with normal brains.

FIGURE 1-1. Dopamine: For dopamine receptor type 2 (D2) antagonist medications, the affinity with which the drug binds the D2 receptor predicts the drugs potency as an antipsychotic, supporting the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. (From Bear MF, Connors BW, Paradiso MA. Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.)

Glutamate

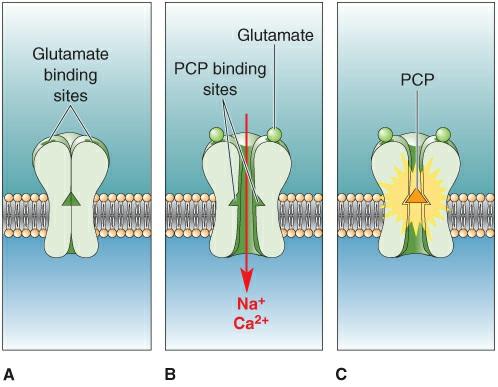

Glutamate dysfunction may contribute to schizophrenia. Clinical observations revealed that drugs (such as ketamine and phencyclidine [PCP]) that block the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channel can produce psychotic symptoms in humans (Fig. 1-2). Similarly, psychotic symptoms are prominent in individuals with anti-NMDA encephalitis, an autoimmune condition associated with antibodies directed against the NMDA receptor.

FIGURE 1-2. Glutamate: The drug phencyclidine (PCP) can block the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor channel and is associated with hallucinations and paranoia in humans. Similarly, autoimmune reactions against the NMDA receptor (known as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis) can produce a range of psychotic symptoms. (From Bear MF, Connors BW, Paradiso MA. Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.)

Alterations in prefrontal cortical GABA interneurons are most strongly linked to cognitive impairments in schizophrenia. There do not appear to be reductions in overall GABA interneurons in the prefrontal cortex but the synthetic enzyme (GAD67) for GABA is lower in a subset of these neurons, among other indicators of altered GABA function such as altered GABA reuptake.

More recent studies have focused on structural and functional abnormalities through brain imaging of patients with schizophrenia and control populations. No one finding or theory to date suffices to explain the etiology and pathogenesis of this complex disease.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

History and Mental Status Examination

Schizophrenia is a disorder characterized by symptoms that have been termed positive and negative symptoms, by a pattern of social and occupational deterioration, and by persistence of the illness for at least 6 months. Positive symptoms are characterized by the presence of unusual thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors (e.g., hallucinations, delusions, agitation); negative symptoms are characterized by the absence of normal social and mental functions (e.g., lack of motivation, isolation, anergia, and poor self-care). The positive versus negative distinction was made in a nosologic attempt to identify subtypes of schizophrenia, as well as because some medications seem to be more effective in treating negative symptoms. Clinically, patients often exhibit both positive and negative symptoms at the same time. Although subtypes of schizophrenia are no longer recognized, it is worthwhile to note that a preponderance of negative symptoms portends a poorer prognosis. Table 1-2 lists common positive and negative symptoms.

TABLE 1-2. Positive and Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia

Negative Symptoms

Affective flattening or blunting

Decreased expression of emotion, such as lack of expressive gestures

Alogia Literally “lack of words,” including poverty of speech and of speech content in response to a question

Avolition apathy

Positive Symptoms

Hallucinations

Decreased energy toward self-care, work/school, movement

Auditory, visual, tactile, or olfactory hallucinations; voices that are commenting

Delusions Often described by content; persecutory, grandiose, paranoid, religious; ideas of reference, thought broadcasting, thought insertion, thought withdrawal

Bizarre behavior

Aggressive/agitated, odd clothing or appearance, odd social behavior, repetitive-stereotyped behavior

Based on Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer, 2017.

To make the diagnosis (Table 1-3), two (or more) of the following symptoms must be present: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, grossly disorganized or catatonic (mute or posturing) behavior, or negative symptoms. At least one of the two symptoms must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech. There must also be social or occupational dysfunction. The patient must be ill for at least 6 months, including prodromal periods.

TABLE 1-3. 1-Diagnostic Criteria for Schizophrenia

Delusions

Hallucinations

At least one of the two criteria must come from the first three

Disorganized speech

Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior

Negative symptoms

To diagnose schizophrenia, two symptoms from the above list must be present for at least 1 month and at least one of the symptoms must come from the first three. Symptoms must cause functional impairment and the overall period of symptoms must be at least 6 months.

Patients with schizophrenia generally have a history of abnormal premorbid functioning. The prodrome of schizophrenia includes poor social skills, social withdrawal, and unusual (although not frankly delusional) thinking, sometimes referred to as magical thinking. Notably, there is a strong correlation between schizotypal personality disorder and development of schizophrenia. Inquiring about the premorbid history may help to distinguish schizophrenia from a psychotic illness secondary to mania or drug ingestion.

Patients with schizophrenia are at high risk for suicide. Approximately 20% will attempt suicide, and 5% will complete suicide. Risk factors for suicide include male gender, age younger than 30 years, poor social support, chronic course, prior depression, and recent hospital discharge.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnostic evaluation for schizophrenia involves a detailed history, physical, and laboratory examination, preferably including brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although there is no diagnostic laboratory or imaging finding for schizophrenia, cerebral ventricular enlargement is typical. Medical causes, such as neuroendocrine abnormalities and psychostimulant use disorder, and such brain insults as tumors or infection, should be ruled out.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of an acute psychotic episode is broad and challenging (Table 1-4). Once a medical or substance-related condition has been ruled out, the task is to differentiate schizophrenia from a schizoaffective disorder, a mood disorder with psychotic features, a delusional disorder, or a personality disorder.

TABLE 1-4. Causes of Acute Psychotic Syndromes

Major Psychiatric Disorders

Acute exacerbation of schizophrenia Depression with psychotic features

Atypical psychoses (e.g., schizophreniform) Mania

Drug Use and Withdrawal

Alcohol withdrawal Phencyclidine (PCP) and hallucinogen use

Amphetamines and cocaine use

Prescription Drugs

Anticholinergic agents

Digitalis toxicity

Sedative-hypnotic withdrawal

Glucocorticoids and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

Isoniazid

l-DOPA (3,4-dihydroxy-l-phenylalanine) and other dopamine agonists

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents

Withdrawal from monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

Other Toxic Agents

Carbon disulfide Heavy metals

Neurologic Causes

AIDS encephalopathy

Brain tumor

Complex partial

Infectious viral encephalitis

Lupus cerebritis

Neurosyphilis

seizures

Early Alzheimer’s or Pick’s disease Stroke

Huntington’s disease Wilson’s disease

Hypoxic encephalopathy

Metabolic Causes

Acute intermittent porphyria

Cushing’s syndrome

Early hepatic encephalopathy

Nutritional Causes

Niacin deficiency (pellagra)

Thiamine deficiency (Wernicke-Korsakoff’s syndrome)

Hypo- and hypercalcemia

Hypo- and hyperthyroidism

Paraneoplastic syndromes (anti-NMDA [Nmethyl d-aspartate] receptor encephalitis; limbic encephalitis)

Vitamin B12 deficiency

From Rosenbaum JF, Arana GW, Hyman SE, et al. Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Therapy, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

MANAGEMENT

Antipsychotic agents are primarily used in treatment. These medications are used to treat acute psychotic episodes and to maintain patients in remission or with long-term illness. Antipsychotic medications are discussed in Chapter 15. Combinations of several classes of medications are often prescribed in severe or refractory cases. Psychosocial treatments, including stable reality-oriented psychotherapy with increasing support for cognitive behavioral therapy, family support, psychoeducation, social and vocational skills training, and attention to details of living situation (housing, roommates, daily activities)

are critical to the long-term management of these patients. Complications of schizophrenia include those related to antipsychotic medications, secondary consequences of poor health care and impaired ability to care for oneself, and increased rates of suicide. Once diagnosed, schizophrenia is a long-term remitting/relapsing disorder with impaired interepisode function. Poorer prognosis occurs with early onset, a history of head trauma, or comorbid substance abuse.

SCHIZOAFFECTIVE DISORDER

Patients with schizoaffective disorder have psychotic episodes that resemble schizophrenia but with prominent mood disturbances. Their psychotic symptoms, however, must persist for at least 2 weeks in the absence of any mood syndrome.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Lifetime prevalence is estimated at 0.5% to 0.8%. Age of onset is similar to schizophrenia (late teens to early 20s).

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for schizoaffective disorder are not well established but likely overlap with those of schizophrenia and affective disorders.

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of schizoaffective disorder is unknown. It may be a variant of schizophrenia, a variant of a mood disorder, a distinct psychotic syndrome, or simply a superimposed mood disorder and psychotic disorder.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

History and Mental Status Examination

Patients with schizoaffective disorder meet the diagnostic criteria for psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia and also meet criteria for a major mood disturbance (mania or major depressive episode). They must also have periods of at least 2 weeks during some point in their illness in which they have psychotic symptoms (delusions or hallucinations) without a major mood disturbance. Mood disturbances need to be present for a substantial portion of the illness.

There are two subtypes of schizoaffective disorder recognized in the DSM-5, depressive type and bipolar type, which are determined by the nature of the mood disturbance episodes.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnostic evaluation for schizoaffective disorder is similar to other psychiatric conditions and involves a detailed history, physical, and laboratory examination, preferably including brain magnetic resonance imaging. Medical conditions producing secondary behavioral symptoms should be ruled out.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Mood disorders (depressive or bipolar disorders) with psychotic features, as in mania or psychotic depression, are different from schizoaffective disorder in that patients with schizoaffective disorder have persistence (for at least 2 weeks) of the psychotic symptoms after the mood symptoms have resolved. Schizophrenia is differentiated from schizoaffective disorder by the absence of a prominent mood disorder in the course of the illness. It is important to distinguish the prominent negative symptoms

of the patient with schizophrenia from the lack of energy or anhedonia in the depressed patient with schizoaffective disorder. More distinct symptoms of a mood disturbance (such as depressed mood and sleep disturbance) should indicate a true coincident mood disturbance.

MANAGEMENT

Patients are treated with medications that target the psychosis and the mood disorder. Typically, these patients require the combination of an antipsychotic medication and a mood stabilizer. Mood stabilizers are described in Chapter 17. An antidepressant or electroconvulsive therapy may be needed for an acute depressive episode. Psychosocial treatments are similar for schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia. Complications of schizoaffective disorder include those related to antipsychotic and mood stabilizer medications, secondary consequences of poor health care and impaired ability to care for oneself, and increased rates of suicide. Prognosis is better than for schizophrenia and worse than for bipolar disorder or major depression. Patients with schizoaffective disorder are more likely than those with schizophrenia but less likely than mood-disordered patients to have a remission after treatment.

SCHIZOPHRENIFORM DISORDER

Essentially, schizophreniform disorder is diagnosed when an individual has symptoms of schizophrenia that last between 1 and 6 months. The diagnostic criteria do not require the presence of impaired social or occupational functioning, although they can be present.