A Note to the Reader

This book is titled Bioprinting. Just one word. Seems simple enough. But it requires some explanation. In 2016 a group of 19 distinguished scientists published a paper titled “Biofabrication: Reappraising the Definition of an Evolving Field.” The paper proposed a “refined working definition” of bioprinting among other clarifications.1 The proposed definition isn’t the one used in this book.

The technology that led to bioprinting is called 3D printing, invented in 1984 by Chuck Hull. 3D printing uses plastic or metal to build a three-dimensional object layer-by-layer. This build process is distinct from machining by removing portions from a block or casting by pouring molten material into a mold. About 15 years after 3D printing was invented, various scientists began to think seriously about using the technique to print living matter such as cells. Bioengineer Thomas Boland, then at Clemson University, tinkered with a commercial inkjet printer to dispense proteins, bacteria, and cell solutions instead of conventional ink. He published his results. Others soon joined in the fun.

As more people tried their hand at it, bioprinting seemed like a reasonable way to describe what they were doing. But as so often happens when clever people start to mess about, they came up with alternative ways to do what they had first started out doing. It wasn’t long before folks were able to build three-dimensional objects that included living cells—without necessarily doing so layer-by-layer.

If they were using computer-controlled machines and if the three-dimensional result of the method they thought up still resembled the result of layer-by-layer building, it was all too easy for the “popular and journalistic media” to envelop their different practices under the heading of bioprinting.2

The publication on biofabrication that I’ve cited suggested specific definitions for fields such as bioprinting and bioassembly, taking them to be complementary strategies within the larger realm of biofabrication. Bioprinting describes computer-aided transfer processes for patterning and assembling of living and non-living materials by direct spatial placement and arrangement. Bioassembly describes automated assembly of preformed cell-containing building blocks generated by cell-driven selforganization. According to the paper, both bioprinting and bioassembly may involve layer-by-layer deposition of cells and other compatible material, but neither is restricted to this approach. Biofabrication encompasses both bioprinting and bioassembly and also includes subsequent tissue maturation processes.

What it comes down to is that in this book, I’ve knowingly conflated bioprinting, bioassembly, building biological constructs layer-by-layer, and subsequent tissue maturation processes. My desire was to cut a broad swath through the present-day

scientific literature. So I must provide this Note to the Reader for taking liberties with the efforts of experts to tease apart these closely related fields. Mea culpa.

On a similar subject, the majority of the studies I’ve presented in this book print living cells. These experiments typically print biological or non-biological material in addition to printing cells. But there are cases in which no cells are printed. And sometimes the researchers seeded the cells onto a bioprinted matrix. Seeding cells means the experimenters spread a defined amount of a cell suspension onto the bioprinted matrix, typically using a pipette (a slender tube). On rare occasions, cells aren’t added by bioprinting or seeding—for example, an experiment that printed substances encouraging the directed growth of host cells. So it’s important to acknowledge upfront the diversity of experimental methods included in this book, all subsumed under the rubric of bioprinting.

One last item: the definition of a bioink. Just as the term bioprinting has assumed different meanings in common usage, so too has the notion of a bioink. This will sound familiar, but in 2019 a group of 15 distinguished scientists published a paper titled “A Definition of Bioinks and Their Distinction from Biomaterial Ink.”3

The authors observe that the “apparent definition of the term bioink” has become increasingly divergent. They propose that bioinks should be defined as “a formulation of cells suitable for processing by an automated biofabrication technology that may also contain biologically active components and biomaterials.”4 They recommend two designations—bioink and biomaterial ink—be used in place of the single word bioink.

In this book we will simply use the term bioink rather than the suggested two terms. This is in keeping with the current literature. We will be explicitly clear when a printer is depositing cells or when it is depositing a plastic polymer, for example.

Nevertheless, we still haven’t shared with the indulgent reader what constitutes a biomaterial or a biomaterial ink. The 2019 paper I’ve just cited does skillfully differentiate between a bioink and a biomaterial ink. In doing so, it also directs you to yet another scholarly paper on the proposed definition of a biomaterial.5 In thirteen wellcrafted pages, the author of that paper puts forth a compelling argument for a radically different definition of a biomaterial than has been used in times past.

And now I must unceremoniously stop.

I felt duty-bound to write this note to the reader. And I started with the best of intentions. But by this point I’m reminded of a story you likely know:

In an oft-told variation of the Hindu myth of cosmology, a young boy asks his father what holds up the Earth. Amused, the father assures his son that the world rests on the back of a very large turtle. “But what holds up the turtle?” the boy asks. After brief reflection, the father says, “A huge elephant.” “But,” the boy continues, “what is under the elephant?” Sensing that he is rapidly losing control of the conversation [just as I was losing control of A Note to the Reader], the father finally exclaims, “Son, it’s elephants all the way down from there!”6

Foreword

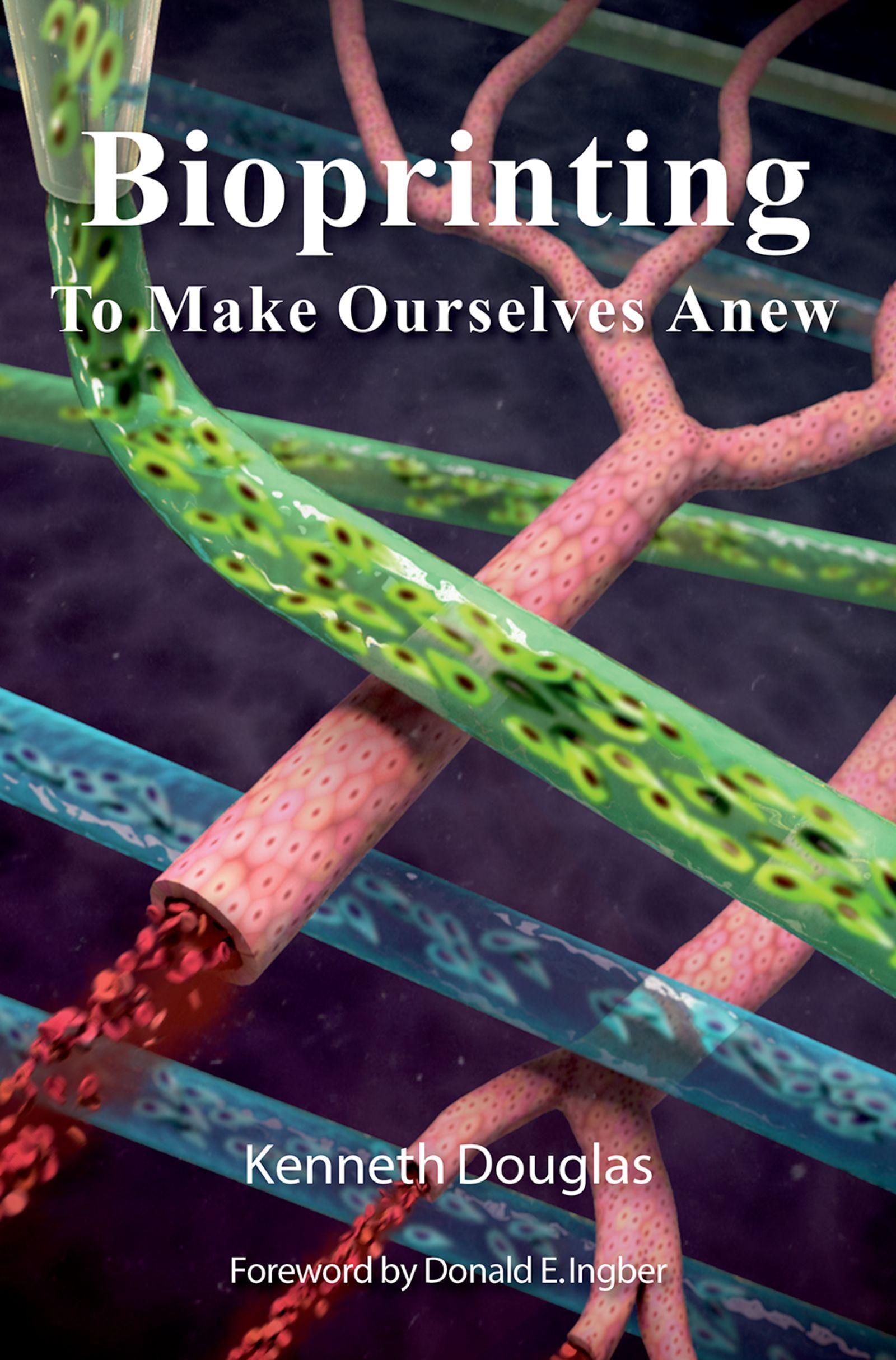

I am not sure why Ken Douglas invited me to write the Foreword to this book, but here I am. I do not know the author. He sent me an email explaining that he had written what he believes to be (and I agree) the first book on bioprinting written for the lay audience. He also went on to explain that “a good deal of the material in the book is work done at the Wyss Institute. Also, the book’s cover will be graced by an illustration arising from work at the Wyss Institute.” As the Founding Director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, where many of the examples that are used to highlight the major accomplishments in this field were carried out as part of our 3D Organ Engineering Initiative, this was a pretty good pitch. Furthermore, once I read the book, I realized that Ken highlighted a great deal of my own work that helped to launch the fields of mechanobiology, tissue engineering, and organs-on-chips, from which bioprinting emerged. But what Ken apparently did not know is that I had actually been bitten by the 3D printing bug myself in the late 1990s, even before the field of bioprinting first emerged, and so accepting this offer was an easy decision.

In 1996, I was invited to attend a meeting of the Defense Science Board, a committee of about twenty leading scientists and engineers who advise the Pentagon on scientific and technical matters of special interest to the U.S. Department of Defense. In the past, the scientists who presented updates to the committee on newest advances in their fields had largely been chemists, physicists, material scientists, and engineers because the focus of the military was on nuclear and chemical warfare, advanced materials for armaments, and computer-based communications and control. But everything changed after the first Iraq war, when the U.S. government discovered that Saddam Hussein had amassed a vast amount of biological warfare agents and that he had rockets armed with deadly anthrax. Due to the significance of this threat and the difficulty of the challenge to rapidly develop relevant countermeasures, the military asked the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to take on this task. DARPA was founded immediately after Sputnik to ensure that the United States would never be surprised like that again. Its main purpose is to “maintain our nation’s technological superiority for the defense of the United States” by focusing on challenges that may take 20–30 years to solve.

I was invited to speak to the Defense Science Board because, due to this new biological threat, they now badly needed input from experts who understood medicine as well as molecular cell biology and infectious disease. The biologists and physicians they sought also needed to be able to communicate and interact effectively with physicists, chemists, engineers, and military experts, and apparently I fit the bill. In my lecture, I explained to them how molecules physically self-assemble to form

three-dimensional filamentous cytoskeletal networks that give cells their shape, as well as how cells and molecular scaffolds join together to form tissues and how tissues combine to create organs during embryo formation, using a design principle known as tensegrity. Tensegrities are structural networks composed of opposing tension and compression elements that balance each other, thereby creating isometric tension or a tensile prestress that stabilizes the entire structure. Our bodies use the same principle to stabilize themselves as they are composed of multiple stiff, compressionbearing bones interconnected by tensed muscles, tendons, and ligaments, and the tone or prestress in our muscles governs whether we are flexible or rigid. Thus, as Ken describes in this book, my work focused on the central role of mechanics in biology, and I described living cells and molecules as physical materials. This is not what the audience of physicists, chemists, and engineers expected from a biology lecture, and they were reassured to learn that the laws of physics also apply at this size scale, and at this level of complexity.

After my presentation, a DARPA program manager by the name of Shaun Jones came up to me and explained that one of the biggest immediate challenges the military faced was redesigning their uniforms so that they could protect soldiers from biological pathogens and allow them to continue to operate in the battlefield. The existing protective gear for soldiers was essentially thick rubber overalls that zipped tight like deep sea diving outfits. They completely prevented entry of chemicals and infectious agents; the only problem was that the soldier heated up to deadly temperatures in about 30 minutes due to the heat generated by his own body in a closed space, much like the beautiful blond lover of James Bond who died from being painted gold in Goldfinger. Then Shaun explained that “there’s a huge opportunity out there for anyone who has vision and can come up with a solution to this problem. Do you think you could make synthetic materials that behave like living cells?”

I explained that, in fact, I had helped to found a biotech company called Neomorphics, Inc., with Jay Vacanti and Bob Langer a few years before that engineered artificial skin by combining cells isolated from human foreskin with a felt-like lattice of synthetic polymers made from surgical suture materials. But that tissue engineering approach was too conventional for Shaun, who replied,

No, no, what I’m thinking is more like an incredibly flexible condom that is so strong and resilient that you can climb into it and cover your entire body. It has to allow heat and moisture to pass, but it must prevent the passage of all biologicals, and it would be great if it also kills any pathogen it contacts.

A few months later, a newly formed company I created called Molecular Geodesics, Inc., was awarded a DARPA contract on “Biomimetic Materials for Pathogen Neutralization.” The concept was to build flexible porous fabrics that have great strength and resilience, as well as solid-phase biochemical processing activities, much like the molecular cytoskeleton that gives living cells their shape, but in this case the immobilized enzymes would inactivate pathogens that pass through the network of

the fabric while allowing heat to pass. As I had previously shown that living cells stabilize their shape and internal cytoskeleton using tensegrity architecture, I proposed to use the same design principle to build these bioskins. But how could one build structures with this type of complex 3D architecture at the microscale?

In my search for a solution, I discovered the emerging field of solid free-form fabrication that was being used by industry to rapidly prototype parts with complex 3D forms. The first technique I learned about was stereolithography [usually known as 3D printing], in which computer-assisted design software is used to construct an image of a 3D structure of any arbitrary shape, and then it is computationally cut into many horizontal sections like a deck of cards. To build the structure, a thin (a few thousandths of an inch) layer of a solution containing a light-sensitive liquid polymer is poured over the surface of a square chamber. A moveable ultraviolet laser then rasters back and forth across the entire surface line-by-line and emits brief bursts of light at microscopic points that correspond to pixels where the 3D computer image of the structure is sliced by the first horizontal cross section through the image. This solidifies the plastic dot-by-dot, but only in regions that correspond to the material to be built; all of the remaining solution remains liquid. By lowering the platform a few thousandths of an inch at a time, repeating this process layer-by-layer from bottom to top of the computer image, and washing it free of the unpolymerized fluid, a solid form is created that exhibits the exact same 3D shape and internal fine network architecture on the microscale as that originally designed on the computer. Molecular Geodesics used this type of computer-based design and manufacturing strategy to create 3D tensegrity materials, which were first optimized for their material properties in silico using engineering analysis software.

Needless to say, the 3D printing methods in 1997 were limited in resolution, and the materials that could be used were entirely rigid and inorganic (e.g., polymers, ceramics, and metals), and hence not optimal for our application. Thus, we never fabricated bioskins with the necessary fine structure and flexibility required by the military. Molecular Geodesics eventually changed its name to Tensegra, Inc., and moved into the medical device space, using a similar laser-based, layer-by-layer building approach with titanium metal to build medical devices such as artificial lumbar discs. Although these did well when implanted into large animals, the company died along with the fall of the Twin Towers the week of September 11, 2001, just about the same time similar 3D printing methods were being hijacked by a handful of scientists and engineers who developed ways to print biological materials, including living cells, in defined 3D forms, thereby creating the field of bioprinting.

In this book, Ken Douglas takes off where my story ended and tells how bioprinting first emerged at the turn of the 21st century, the enormous potential it offers for transforming the field of organ transplantation, and the real challenges that must be overcome in order for it to succeed and have an impact on the future of health care. He covers a huge range of biology because this is precisely what the field of bioprinting is trying to do. Researchers seek to 3D print living cells, and the extracellular matrix scaffolds in which they live, to recreate living replacements for virtually every type

of organ in our bodies: liver, lung, kidney, muscle, bone, skin, brain, and so on. Ken attempts to bring the reader up to speed on the structure–function relations of each of these organs while also introducing them to basic concepts in biology, physiology, medicine, physics, and engineering. It’s a challenge, and readers might get confused in parts, but the tale is compelling. It is a story of creativity, drive, perseverance, and passion, and it is told by recounting the personal stories of many of the key scientists who have led the chase, much as I conveyed my own story relating to 3D printing of bioskins.

The field of bioprinting is growing rapidly, and the various elements that contribute to the process must be refined and optimized to make it a success. This involves continuously developing better sources of organ-specific stem cells, designing building materials with enhanced properties and fugitive inks that can be more easily removed selectively, accelerating the speed of fabrication, and discovering how to let the living cells that are printed finish the design process on their own. After all, our bodies form in the embryo entirely through the action and self-assembly of living cells, without any requirement for blueprint, architect, or manufacturing process. In the end, this field will be confronted with real-world challenges, such as scaling up of manufacturing, fidelity of control, reproducibility, and the ultimate killer of breakthrough medical technologies: cost. Only time will tell whether bioprinting can survive this gauntlet of technical and commercial challenges. But the potential is huge, and as always, technology fallout, scientific value, and recruitment of great young minds into science and engineering will likely come from pursuing this new path of investigation, even if it does not lead to the precise products we expected in the beginning.

Donald E. Ingber, M.D., Ph.D. Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology

Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital

Professor of Bioengineering

Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

Founding Director and Core Faculty

Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering

Harvard University

Preface

I was gobsmacked. Absolutely gobsmacked.

For a long moment I was rooted where I stood, like a male Lot’s wife turned into a pillar of salt.1 Then I burst out, “What!”

I’d come in for my weekly physical therapy session. Nancy—office manager, receptionist, insurance billing doyenne, and spiritual anchor of the clinic—wasn’t at her desk. She might have been in a back room or out depositing a fistful of checks at the bank. Chris, my physical therapist, was in his treatment room finishing up notes from his previous patient. Then he came out and saw me standing in front of Nancy’s desk.

“Nancy will be out for awhile. We’re not sure at this point whether it will be six months or maybe less. We’ve hooked up the computers so she can work from home. She had a kidney transplant on Tuesday. She’s doing well.”

That’s when I blurted out “What!” in my utter astonishment. This was Friday. I had last seen her the previous Friday and she looked in good health. I had no idea that any such thing was supposed to happen. Chris filled me in a little. Nancy had been living with deteriorating kidneys for a long time yet she didn’t show any sign of it. As her condition worsened she’d been placed on the recipient list for a donated kidney. She had a knapsack packed so she could go down from Boulder to the Denver hospital at a moment’s notice, if and when she got the call that they had a donor match for her.

I had my physical therapy session with Chris. I didn’t want to pry and didn’t ask him too many questions about Nancy’s situation. But I couldn’t stop thinking about her. I’d known Nancy for about 10 years. Like me, she was an avid reader. We chatted about many of the books we’d read, from Dickens to Dostoyevsky. And she was an opera lover like me. We talked opera and once or twice when it wasn’t too busy at her desk we would watch an opera excerpt on her computer. Now I’d learned that Nancy had been near death. Thank goodness she’d been lucky and they had found a donor match for her.

When I went home, the first thing I did was write her a get well card. Then my mind played connect-the-dots and I remembered the journal articles I’d skimmed on bioprinting. I dimly grasped that bioprinting originated from 3D printing—the technology that’s all the rage where folks use a computer-controlled device to build up three-dimensional objects layer-by-layer. But instead of using plastic or metal to make a statuette of Yoda the Jedi Master or a new twist on a socket wrench, a band of adventurous scientists are using living cells to make pieces of human tissue. Skin, cartilage, bone, muscle, nerve, liver, heart, lung, kidney—they’re all in play. And the quest is for an organ; even a mini-organ would be a pippin.

In many professional, peer-reviewed articles on bioprinting they mention the shortage of donor organs for people in need of transplants. And of the many on the waiting lists

who die while waiting. In the United States, the number of people needing an organ transplant is over 121,000.2 Kidneys are the organs most in demand: over 100,000. I didn’t yet know the details of Nancy’s personal story. More on that in a moment. But on the Friday I first learned of her kidney transplant I wondered about the prospects for bioprinted kidneys and I threw myself into the bioprinting literature with passion.

In my reading I was navigating choppy waters. I took my Ph.D. in physics, though I’ve spent my academic career in highly interdisciplinary work at the junction of physics and biology. By some unaccountable trick of the mind I thought that would be sufficient to fly through the pages to the feast of reason like a hummingbird zipping through the garden to the welcoming nectar of a trumpet vine. However, I wasn’t encumbered by previous familiarity with the terms and concepts that came up again and again with the result that when I read the journal articles on bioprinting far into the night I could follow them only to a degree. Words like extracellular matrix, rheology, innervation, vascularization, bioreactors, microfluidics, and organ-on-a-chip percolated through the articles and I found their substance elusive. After I dug into these topics and went back to an article, it was as if I was reading it for the first time. And I felt a rush.

That helped to make my reading smoother sailing. And there was a serendipitous bonus. When I started to ferret out the terminology I found the backstory enthralling too. Take innervation as an example. This refers to the distribution of nerves in a tissue or organ. When a nerve is ruptured, the body has a limited capacity to repair the break. A bioprinted nerve graft can bridge the gap and, in animal studies, provides a conduit to support nerve regrowth. Bioprinting avoids the risks due to secondary surgery to harvest a nerve from another part of the body.

I decided to seek out major players in bioprinting and talk to them about their work and their world, to learn more about the backstory. Reading about innervation I found that the work of Gabor Forgacs (pronounced Forgatch) on biofabricated nerve grafts was seminal. I was fortunate to be able to speak to him.3

Forgacs came to bioprinting circuitously, having started in Hungary as a theoretical physicist who wanted to be a doctor but couldn’t stand the sight of blood.4 As he joked, he did the next best thing and married a doctor.5 After coming to the United States, he collaborated with biologist Malcolm Steinberg at Princeton University. Steinberg’s famous insight into how dissimilar cell types sort themselves out in the developing embryo—once considered a puzzling if not to say inexplicable phenomenon—is called the differential adhesion hypothesis.6,7,8,9,10 He came up with his idea in the 1960s, melding elements of both biology and physics. His concept is that the embryo employs liquid-like tissue spreading and cell segregation that arise from differences in the adhesiveness (the stickiness) of individual types of tissue.

Steinberg’s differential adhesion hypothesis, though conceived to describe embryonic development, informs much of the work Forgacs has contributed to bioprinting.

Not long before he took to bioprinting, Forgacs published detailed studies on the liquid-like properties of a myriad of cell aggregates including heart, liver, and retinal nerve cells.11 In 2000 he accepted an offer from the University of Missouri, where he began to publish his work in bioprinting.

Previously, he had brought his cellular aggregates near to one another and watched as they fused in the same way that liquid drops coalesce à la Steinberg’s hypothesis. Forgacs’ group was the first to do this.12 But creating these cellular aggregates, putting them together, and waiting for them to fuse was tedious and timeconsuming. Then he went to a conference and came cheek-to-jowl with a 3D printer for the first time. It was a portentous encounter for both and neither would ever be the same again.

It wasn’t long before Forgacs started to alter a printer so it could handle his cellular aggregates. He and a number of collaborators transformed the 3D printer into a bioprinter.* In July of 2004, they used it to produce the first non-trivial biological structure.13 Forgacs shared a video with me (including audio) of their bespoke bioprinter completing its task—at which point an experimenter erupts in a spontaneous, ecstatic shout of joy that captures the moment.14

The science in this volume will be rigorous though absent the minute details that scientific technoweenies thrive on, much as we thrive on micronutrients in our food. There’s a lot of serious business connected with bioprinting, the specter of organ donor waiting lists being just one of them. Even so, we can all still cherish and enjoy the science and the scientific backstory, presented with a minimum of technical baggage but without being shallow.

Helmut Ringsdorf is an eminent chemist, well known for successfully bridging the life sciences and materials science. He’s also an advocate for going beyond the precise results of research. “We have to try to look behind the curtain of science, look at the acting scientists and the life they had to live and play in.”15 In this spirit, I’ve spoken to two dozen luminaries in bioprinting. I’ve had the pleasure and privilege of talking science with them and also hearing stories arising from their lives and work, some of which will appear in the book.

We’ll bring this Preface to a close with Nancy’s transplantation story.16

My friend Nancy ignited my interest in bioprinting. If Nancy lived some time in the future her story might have unfolded very differently. A physician might aspirate

* Forgacs was using a bioprinter to precisely position cells. Then he allowed the cells to self-assemble into aggregates by fusion (bioassembly). He was not building a three-dimensional object layer-by-layer. A Note to the Reader elaborates on the convention in this book: the conflation of divergent means of biofabrication in order to cut a broad swath through the present-day scientific literature.

(draw out by suction) cells that were still functioning well from one of her kidneys. Then the clinician would place these cells in a sealed chamber containing a solution with various nutrients and at optimal temperature and pH (optimal acidity or basicity) and perhaps including other support cells to induce a vascular network to form within the growing mass of kidney cells. The physician would take this enlarged aggregation of Nancy’s kidney cells and bioprint a sort of cartridge or cassette enclosing them. The kidney has a naturally occurring area, called the Brödel line, which has a paucity of blood vessels. It’s here that a surgeon would make an incision in one of Nancy’s kidneys to insert the cassette using minimally invasive surgery and with almost no bleeding. Since the cells originated from Nancy’s own kidneys, there would be little fear of rejection and minimal need for immunosuppressant drugs.

Some such scenario is for a future Nancy. The reality at present for my friend and countless others isn’t so straightforward. In fact, at the present time, restoring kidney function is quite problematic. What follows is how one such story unfolded in the here and now.

Nancy had the first indications of her polycystic kidney disease in her early forties. The disease causes numerous fluid-filled cysts to sprout in the kidneys like so many dandelions in a grassy lot. As more and more cysts develop or as the cysts get too large, they interfere with the ability of your kidneys to keep metabolic waste from building to toxic levels. There’s no known treatment for polycystic kidney disease, only treatment for some of the complications it causes, such as high blood pressure.

The disease is an inherited disorder, although Nancy knew of no one in her family who had ever been diagnosed with this malady. About 10 years prior to her kidney transplant she was feeling her usual vibrant self and went in to her primary care physician for a routine physical exam. Part of the exam was a metabolic panel and the blood drawn at her doctor’s office showed high levels of creatinine—metabolic waste. Her doctor referred her to a nephrologist (a doctor specializing in kidney care) who ordered an ultrasound of her kidneys. During the ultrasound Nancy looked at the images and saw a large number of black dots in both kidneys. She knew that something was wrong.

The black dots were fluid-filled cysts. She began to see a nephrologist every three months. Slowly her creatinine levels continued to climb. Then high blood pressure became an issue to be treated. The implacable progression of the underlying disease was slow. Her blood began to show elevated levels of potassium and phosphorus. Her kidneys were just not able to do their job. Despite that, she was still feeling healthy, no pain or fatigue. After some eight years the blood abnormalities became a concern. Her nephrologist asked her to attend Kidney Class at a Denver hospital. Shortly before Christmas of 2014, she went to Kidney Class and it so happened that she was the only one to attend that day. She and the doctor sat down and he explained that dialysis would buy her a little time. Time to hope for a kidney transplant.

She was shocked and terrified. She’d been feeling fit. Married and with a child in college, Nancy was working full-time, taking care of her house, and helping to raise her daughter. Now, after her private Kidney Class, she was terribly depressed. This

was a big reality check. Dialysis seemed like a death sentence for someone who’d been leading such a busy life. And the doctor told her that with kidney transplantation you’re trading one chronic problem (polycystic kidney disease) for another, namely, medications and their side effects for the rest of your life to keep your immune system from rejecting the kidney.

Nancy saw her primary care physician, who recommended that she go to one of the two kidney transplant programs in the state. In March of 2015, she went to a transplant program hospital. It was an all-day meeting with a financial consultant, a social worker, a pharmacist, a medical assistant, a surgeon, and then the doctor who was the head of the kidney transplant program. They were all quite nice and excited. Usually the people that they see in the transplant program are very sick—perhaps diabetic, maybe overweight, smokers, elderly, etc. And here was Nancy, a relatively young person with a positive attitude, working full-time, exercising regularly. Individuals on the transplant team came up to her and said, “You’ll do great!” They were convinced of it. The doctor who was to be her surgeon did an exam. Poking around her abdomen, he said with animation, “Oh this is great, you have plenty of room!” A transplanted kidney is placed in your abdomen. And after all, those doing the transplant want success at their job. They were confident that everything would go well.

Then she was dealt a blow. Blood tests showed that she had a plethora of antibodies that probably arose from her pregnancy and made her body more likely to reject a donated kidney. And her blood type was difficult to match with that of a potential kidney donor. She was a poor fit for 84% of the general population. Nancy was unlikely to get a donated kidney anytime soon.

The transplant team put her on a restricted diet to spare her kidneys. Among other yummies, she couldn’t eat hummus, her favorite food. She was now in the category of severe kidney disease and consequently she was formally eligible for a kidney transplant. Nancy was given a number—a rank on the list of people in dire need of a kidney transplant. The lower the number the better off you are. Anything under 20 and you’re sitting near the top of the list. Her number was 19. She had her presurgical exam to see if there were any comorbidities—any other chronic diseases or conditions. There were not. Nancy, her family, and her doctors played the waiting game, mostly working to keep her blood pressure under control. When she went on the list she prepared her backpack with pajamas, a toothbrush, and a book.

She had been feeling all right. Then fatigue set in. Coming home from a full day’s work she collapsed. Even with a good movie on Turner Classic Movies she’d just fall asleep. A week before Memorial Day of 2016, her transplant coordinator called. “There’s a remote possibility that you might be a match for a kidney. But don’t get your hopes up too high.” The potential donor was on life support. The donor was an intravenous drug user. That increases the risk of HIV, hepatitis C, and other diseases. With a mirthless inflection, Nancy said, “Oh, that’s OK. I’m good. I’ll wait for another possible donor.” The transplant coordinator had her speak to the surgeon. He said, “We’re really glad that you’re feeling fine. But you’re a poor match for 84% of the population. There’s a very small window to find a match for you.” They had tested the donor

kidney. “It’s young and it appears to be disease-free. And we don’t know when another kidney will come along that will be a match for you.” They felt that the young woman with the kidney wasn’t on the streets using dirty needles. The donor was probably a “clean” drug user. The surgeon advised that Nancy be tested further to see if she was a match and, if so, that she take the kidney. She said OK.

She received a call the next day. The good news: The kidney is a match for you. The bad news: You’re fourth on the list for this kidney. So it’s probably not going to be your kidney. On the morning of the next day, Tuesday, the transplant coordinator called again. “Yeah, both the kidneys are spoken for. But you’ll move up on the list if another one comes along.” Nancy took it philosophically. “I went to work and said to myself, ‘Great, I don’t have to have a surgery today.’ ” She got a little hungry at work and nibbled on a sandwich.

Later, on the same Tuesday morning, another call came through. It was the transplant coordinator once more. “So, have you eaten today?” Nancy said, “Yes, but not much.” The coordinator said, “When can you be at the hospital. It’s go time.” Nancy was exhilarated, scared, and practical. Although she never got to learn the specifics, everything had changed as fast as a somersault. She got her knapsack, and her husband drove her down to Denver to have a kidney transplant.

For three days following her surgery, Nancy lived in the shadowy world of a sleep/ wake cycle persistently disrupted. Nurses checking multiple intravenous lines and giving her medications; the beep-beep-beep of machines monitoring her heart rate and temperature and at set intervals the whoosh-whoosh-whoosh of the cuff inflating to measure her blood pressure, clamping down on her arm and then loosening its grip like an apparition in a dream; the cloying hospital smell of disinfectant. She did get to read a little bit. The book was Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. She joked, “A nice uplifting, entertaining choice!”

Two days after her surgery, when she went to the bathroom to brush her teeth she looked in the mirror. “I looked like a different person,” she said. Over the years, she had become very pale. Being ashen had become the norm. Now she was positively flushed—like she would have looked in her twenties riding her bike up a mountain trail. And her sense of taste and smell returned. They were lost when she was running poor blood through her body for all the years her kidneys were in crisis. I asked her what her feelings were at this point. She said, “Gratitude. Gratitude.”

On Friday, she was free to go home. As she was walking out of the transplant department toward the elevator, a member of the transplant team asked her, “Did you ring the bell?” Sure enough, there was a rope attached to a big ship’s bell. When every successful transplant patient leaves this hospital, they get to ring the bell. Nancy says she rang the bell “maybe louder and harder than anybody ever had!” Bong, bong, bong! On the drive home she kept saying to her husband, “Everything is so gorgeous, the sunshine streaming in, the trees, the mountains.” She was seeing the world for the first time, again.