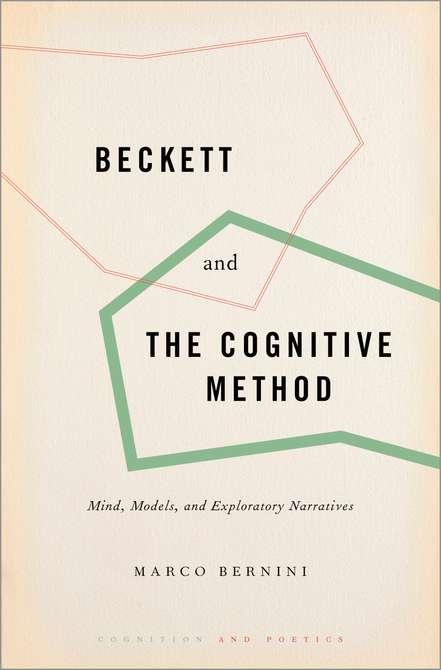

Beckett and the Cognitive Method

Mind, Models, and Exploratory Narratives

Marco Bernini

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021940054

ISBN 978–0–19–066435–0

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190664350.001.0001

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

CONTENTS

Preface vii

Acknowledgments xvii

1. Modeling the Apparent Self 1

1.1. Awakening in the Bioscope: Wertheimer’s Law, Predictive Self, and Chronotopic Groundlessness 2

1.2. A “Torrent of Meiosis”: Fissions, Relations, and the “Pearl View” Explored 11

1.3. Introspection by Simulation: Inner Third-Person, Polyphony, and Centerless Storyworlds 19

1.4. Toward the “Seed of Motion”: Close and Beyond the Center of Narrative Gravity 33

2. A Brain Listening to Itself 45

2.1. Tracing a Phenomenological Continuum: From the Clinical to the Fictional 46

2.2. Theorizing a Modeling Continuum: From AVHs to Inner Speech 56

2.3. Detuning a Fundamental Sound: Mediacy, Co-Modeling, and the Narrated Self 65

2.4. The Dialogic Cloud: On Memory and Co-Presence 76

3. Synesthetic Innerscapes 85

3.1. Landscapes of Consciousness as Landscapes of Action: Quasi-Perceptual Minds and the Basics of Innerscapes 87

3.2. Sculpting Latencies: Introspective Affordances, Narrativity, and Personal Geographies 92

3.3. Windows of Presence: Inner Ecologies and Dreamlike Worlds 98

3.4. “In the Night That Tells No Tales”: Synesthesia, Narrative, Table Lamps, and Magic Lanterns 109

4. Cognitive Liminalism 122

4.1. The Principle of Liminality: Limens and Limes across Domains 123

4.2. Toward Cognitive Liminalism: Impeded Logomotion and Deflated Narrative Gravity 128

4.3. Residual Teleodynamics and Maximal Prediction Errors: E-Motions, Absential Features, and Cognitive Impenetrability 138

4.4. Cognitive Conceptual Personae: Enacting Sense-Making without Making Sense 152

5. Emergence and Complexity 166

5.1. Against the Aboutness of Complexity: From Narrative Chaotics to Blueprints for Emergence 168

5.2. Neural and Mental Complexity: A Matter of Levels 175

5.3. The Dynamic Core of the Onion: Patterns, Nodes, Signals, and Boundaries 184

Conclusion: Toward a Phenomenogeology of Consciousness and the Co-Modeling of Cognition 195

References 201 Beckett’s Works Cited 223 Index 227

PREFACE

It’s a hard thing, my fine friend, to demonstrate [sufficiently] any of the greater subjects without using models. It looks as if each of us knows everything in a kind of dreamlike way, and then again is ignorant of everything as it were when awake.

Plato [287 b– c] 1995, 277d1–4

The title of this book intentionally takes its reference from T.S. Eliot’s essay on Joyce, “Ulysses, Order, and Myth” ([1923] 2005). It is well known how in this essay Eliot recognizes in Joyce’s writing a new paradigm for the relationship between literature, reality, and experience. For Eliot, Joyce had been responsible for moving from a “narrative method” to a “mythical method,” intended as a new “way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history” (167). Beckett’s cognitive method, this study will argue, is characterized instead by a use of narrative devices as scaffolding1 tools to explore the structure of human cognition, below and beyond the orderly feeling of control that conceals its complex working. This book takes Beckett’s work as a progressive research, through a variety of available artifactual technologies, into what Molloy calls “the laws of the mind” (M, 9). A central tenet of this book is that Beckett innovated a use of narrative elements as means to construct fictional cognitive models for the exploration of human cognition, and that this practice, as Eliot says about Joyce, “has the importance of a scientific discovery” ([1993] 2005, 166).

To make the case for the nature, pragmatics, and consequences of this discovery, this study will delve at length into contemporary cognitive sciences, cognitive narrative theory, and theories of modeling. A few initial remarks on cognitive models and modeling, and on their relationship with the reality

1. The term “scaffolding” is key to theories of extended cognition (see, e.g., Menary 2010) to define the enhancing yet temporary nature of a specific technology, writing included. It is used, quite generously, as an adjective, a verb, or a noun. I realize it might hit hard the ears of literary scholars and readers, but for conceptual consistency I will also use it (if not abuse it) throughout the book.

they aim at investigating, might thus be a necessary opening move. To provide a working definition, models are a selective, abstract, hypothetical simplification of reality, yet with a strong explanatory or exploratory potential (more on this distinction soon). Models do not mimetically represent reality, but allow the exploration of events, processes, and phenomena otherwise elusive, transparent, and phenomenologically inaccessible. When it comes to modeling cognition, this means that models can disclose insights about architectures and laws within the mind that usually go unnoticed or that cannot be spontaneously observed. As McClelland (2009) summarizes, “[t]he essential purpose of cognitive modeling is to allow investigation of the implications of ideas, beyond the limits of human thinking. Models allow the exploration of the implications of ideas that cannot be fully explored by thought alone. As such, they are vehicles for scientific discovery, in much the same way as experiments on human (or other) participants” (16; emphasis added). As Plato has it in the epigraph to this preface, this is why models can help us understand what experience is concealing. This does not mean that cognitive models are entirely detached from reality either, but they should rather be taken as “mediators” (Morgan and Morrison 1999) between reality and its formal investigation: between the mimetic and the synthetic, the experientially knowable and exploratory manipulations into the unknown.

Together with the possibility of simulating the inaccessible, models allow also performing operations that would be impossible in reality, either because impractical, unattainable, or even unethical. In modeling cognition, we can manipulate models of the human mind in ways that will be hard, if not inhuman, to test through experimental conditions or technologies. As Farrell and Lewandosky (2011) note, “[u]nlike people, models can quite literally be taken apart. For example, we can ‘lesion’ models to observe the outcome on behavior of certain localized dysfunction [ . . . ] one can do things to models that one cannot do to people, and [ . . . ] those lesioning experiments can yield valuable knowledge” (27–28). This book will show how Beckett has made of this possibility of lesioning models2 a key operation in his artifactual explorations of cognition. We shall see a variety of localized or more global lesions Beckett operated while crafting models, aimed at targeting specific or broader aspects in human cognition, from levels of self to the temporal structure of consciousness, from inner speech to memory, from sensorimotor and narrative capacity to affectivity and intersubjectivity. The human faculty of

2. Once more, the use of “lesioning” as a verb and a qualifier is quite unheard of outside the cognitive sciences; and an anonymous reader of this book understandably found it nothing less than “barbaric.” If alterative options such as “impairing,” “damaging,” “injuring” are used to define the localized targeting of actual brain processes, when it comes to simulations and modeling, the barbaric use will prevail. As such, this book takes the risk of endorsing it also to describe the specificity of Beckett’s simulatory operations.

[ viii ] Preface

inflicting unethical lesions is referenced many times in Beckett’s work, such as the spinal dog presented in How It Is (1964, 74), which, as Beckett explains to his Swedish translator on March 25, 1963, is a “laboratory dog whose brain and nervous system are mutilated for experimental purposes of the Pavlovian kind” (BL III, 533). Beckett’s fictional cognitive models allow more ethical procedures, but with a similar experimental horizon, in lesioning cognitive processes, laws, properties, dynamics beyond the limits of human thinking, often providing an otherwise impossible phenomenological access to the threshold of what makes us human.

This book therefore articulates a theoretical account of Beckett’s works as cognitive models for their selective, idealized nature, at the mediating crossroad between the mimetic and the synthetic; for their lesioning function that reveals hidden structures, laws, and dynamics in the mind; and for their possibility of scaffolding operations that would be impossible without them or, more precisely, before their active construction. Following recent cognitive views of writing as a process of thinking-in-action (see Menary 2007a), in fact, this study will assign to the very act of shaping fictional cognitive models an agentive role. In particular, this book tentatively argues that the construction of fictional cognitive models might have worked for Beckett as a scaffolding practice of introspection, conducted through the shaping of simulatory storyworlds (what I will call “introspection by simulation”). If the so- called “hard problem” (Chalmers 1995) in cognitive sciences is to account for how conscious states arise out of the physical matter in our brain, the hard problem of the representation of consciousness in literature can be considered to be understanding how writers have been able to encode mental states and cognitive processes out of their own individual mind. To say, as David Lodge claimed in his foundational essay on consciousness in the novel (2002), that “literature is a record of human consciousness, the richest and most comprehensive we have” (10), is at the same time intuitively correct, yet potentially misleading and certainly not applicable to Beckett.

If the theoretical focus on the narrative modes for the narrative representation of consciousness has produced invaluable works (see, e.g., Cohn 1978; Sotirova 2013; Mahaffey 2013), theorizing how writers have been able to transduce or codify experiential data into fictional minds is to date relatively ignored (for an exception, see Colm Hogan 2013a). We need some hypotheses about how consciousness is introspectively accessed by writers, before being textually recorded or represented. This is why this book takes on also the contemporary debate about a reconceptualization of introspection as a practice that can be trained and scaffolded by external tools and actions such as, I will argue, the making of storyworlds and the molding of fictional minds. However, if for more mimetic authors introspection is arguably a necessary precondition to the creation of lifelike storyworlds and fictional minds (i.e., an introspection for simulation), with Beckett, this

x book argues, there is a reciprocal, looping causality between the shaping of artifacts and introspective practice, whereby the modeling of narrative devices has a scaffolding role for introspective action, and vice versa (i.e., introspection by simulation).

Alongside theory of modeling, this book will closely engage with theories and models from contemporary cognitive sciences. In this respect, this study is intended to be a contribution to the field of cognitive literary studies. More than twenty years from the call for a “cognitive narratology” (Jahn 1997) and from what are considered its foundational works (e.g., Fludernik 1996; Ryan 1991; Herman 2003), the field is still in search of a unified definition, as testified by the variety of umbrellas it is sheltering under such as “cognitive poetics” (Stockwell 2002), “cognitive humanities” (Garratt 2016), “cognitive literary science” (Burke and Troscianko 2017). This plurality of labels mirrors a plurality of commitments (from heavier to lighter engagements with cognitive scientific theories), methods (empirical and theoretical), and objects of research. One of the most productive areas is certainly focusing on the act of reading, consciously in continuity with earlier works on readerresponse theory (notably Iser 1978), which are updated with new empirical (see., e.g., Miall 2006; Bortolussi and Dixon 2003; Kuzmičová et al. 2017; Alderson-Day, Bernini, and Fernyhough 2017; Armstrong 2013; 2020) and theoretical (see, e.g., Popova 2015; Caracciolo 2014; Kukkonen 2014; Polvinen 2016) approaches, theories and research questions. Since Beckett’s fictional cognitive models, similarly to thought experiments which are produced in the “laboratory of the mind” (Davies 2010, 63) and that “prescribe imaginings about themselves” (Toon 2010, 82), need to be activated by readers’ imagination to “run” as simulations, references to this new wave of research on reading will be recursively made.

However, this book more closely aligns with the still scarce cognitive literary examinations of individual authors, such as Patrick Colm Hogan’s study on Ulysses and the Poetics of Cognition (2013b) or Emily Troscianko’s Kafka’s Cognitive Realism (2014; for a comparative study on multiple authors across different genres, instead, see Young 2010). Either implicitly or explicitly, these studies share with mine the view that literary authors might have been able to turn literature into a tool for cognitive investigation, and the idea that we need cognitive science to better know where to look for their findings. In the words of Patrick Colm Hogan (2013), these approaches assume that literary texts might have “captured something in the nature of human psychological processes [ . . . ]. As such, the literary representation of particular minds should be illuminated by empirical findings on the structures and processes of human cognition and affection” (151). Importantly, a core point in my study is that cognitive approaches to literature should neither serve to account for a prescience of literature over cognitive sciences nor to treat literature as an

ancillary exemplification of cognitive scientific problems or debates. Rather, cognitive science should be used to understand the specificity of literature as an autonomous field of research into cognition, because, as Colm Hogan also notes, “if a psychological novel has in fact captured something about mental processes, it should have its own independent validity” (151). And similar to cognitive scientists, different authors might have used a different method for investigating the mind, leading to different insights into a particular problem, process, or experience. This does not entail that an author has to be faithful to our everyday phenomenological experience, but like cognitive scientists she can use the technology of literature to go beyond appearances and everyday feelings to investigate how a specific process works underneath perception.

Troscianko (2014), for instance, suggests that Kafka’s work is “cognitive realistic in its evocation of, for example, visual perception” because “that evocation corresponds to the ways in which visual perception really operates in human minds” (2). Something similar, but at the same time more radical, will be argued about Beckett. The idea of literature being capable of evoking hidden structures is to some extent a softer claim than saying that literary devices are used as models to explore and reveal these layers, laws, and processes. In this study, the active role of narrative as a technology (used by Beckett in a variety of media technologies) is constantly foregrounded as a key part of Beckett’s cognitive method. Also, we shall see how Beckett’s modeling often targets processes that are, unlike visual cognition, way below, beyond, or developmentally before everyday phenomenological levels of awareness, thanks to the scaffolding, exploratory potentiality of fictional cognitive models as vehicles for scientific discovery.

At the minimum of ambition, cognitive literary studies can be seen as providing new interpretations of authors through the lenses of cognitive scientific theories, models, and problems. In spite of the mild (see., e.g., Ryan 2010) or harsh (see., e.g., Adler and Gross 2002; Müller-Wood 2017) criticism that this interdisciplinary framework has received, it should be noted that this enhancement of interpretive possibilities through the integration of frameworks from the study of mind is actually nothing new. It is enough to think at how fertile William James’ concept of “stream of consciousness” ([1890] 2007) has been, and still is, for literary interpreters. In addition, it is fair to say that, unlike the often quite liberal use of James’ image, many cognitive literary scholars are usually much more directly aware of the debate around theories or models they are borrowing. Engaging in depth with cognitive science as a conceptual toolbox for interpretation can thus be in itself a cross- fertilizing encounter. In an otherwise quite skeptical review of the state of the field, Alison Sharrok (2018) has actually provided a very apt description of the interpretive potential of applying to literature “second-generation” cognitive paradigms. The latter are the new philosophical, neuroscientific,

psychological, and phenomenological theories that constitute the scientific backbone of this book. As we shall see throughout this book, these emerging frameworks are countering computational or dualistic models of the mind that they see instead as embodied, embedded, enacted and extended (collectively referred to as “4e cognition”; for a survey, see Rowlands 2010; for second-generation approaches to literature, see the special issue edited by Caracciolo and Kukkonen 2014).

In framing her doubting thoughts about cognitive literary studies, Sharrok nonetheless concedes that “[a]lthough not everyone, (myself included) will want to sign up to the 4E theory and its jargon, I suggest that there are elements in these studies that can remind us to pay attention and help us look at details in a new way. They work, it seems to me, a bit like a Shklovsky’s stone for critics, helping to trip us up and make us look at literature more carefully” (2018, 28). If the accusation of a devious jargon recalls Raymond Picard’s (1969) infamous assault on structuralism’s “intellectual trickery” and “pathological character of [their] language” (50; qt. in Barthes [1966] 2007), Sharrok’s idea that cognitive theories of literature can work as a defamiliarization of interpretive habits is quite exact, and not a secondary achievement in itself. This study would be content even just to provide such a defamiliarizing shift in a reader of Beckett’s work. The more ambitious, but necessarily more speculative goal of this book, however, is to provide an interdisciplinary theory of Beckett’s modeling use of narrative devices as exploratory tools for proper, autonomous, and original cognitive research. If successful, this theory hopefully might also help reconceptualizing literature’s independent validity as a proper field of investigation into the mind.

Both the interpretive and the theoretical components of this book are also aimed at contributing to the field of Beckett studies. Beckett scholarship is an exceptionally thorough, lively, conscientious community, to which this book owes a lot in terms of conceptual, archival, interpretive ground. Everyone in this hermeneutic circle of scholars is well aware of Beckett’s distrust for academia in general, and for philosophical reading of his works in particular. In a couple of oft- cited passages from interviews, when asked about the influence of philosophy in his work, Beckett famously replied that “I am not a philosopher” (Driver [1961] 1979, 23), “I never read philosophers,” “I never understand anything they write” and that in his work “[t]here’s no key or problem. I wouldn’t have had any reason to write my novels if I could have expressed their subject in philosophical terms” (qt. in d’ Aubarède [1961] 1979, 217).

Since Beckett scholars have carefully shown (see Feldman and Mamdani 2015; Van Hulle and Nixon 2013; Feldman 2008; Matthews and Feldman 2020) how actually Beckett did read and take extensive notes on major philosophers such as Leibniz or Schopenhauer, and even niche thinkers such as

[ xii ] Preface

Fritz Mauthner or Arnold Geulincx (Tucker 2012), the question worth asking is why he resisted so firmly any philosophical reading of his work. The answer is probably that he wanted to avoid, as Porter Abbott puts it, “a happy matching of fictional content to philosophical idea, with its implicit relegation of fiction to a second-order discipline in which philosophy is the master and fiction the handmaiden” (81). In other words, Beckett’s statement might be, and arguably should be, taken as admonition to recognize the independent validity of literature in general, and of his work in particular, as a vehicle for discovery operationally distinct from philosophical reasoning and arguments. Instead of rejecting a view of literature as opposed to thinking, though, we might follow Jerome Bruner’s suggestion (1986) to consider the construction of arguments and the practice of storytelling as “two modes of thought.” These modes of thought that rely on different cognitive functioning are ruled by distinct operating principles and “the structure of a well- formed logical argument differs radically from that of a well- wrought story” (11). Consequently, Bruner concludes, “efforts to reduce one mode to the other or to ignore one at the expense of the other inevitably fail to capture the rich diversity of thought” (11). Even before debating whether Beckett’s narratives can be considered as well- wrought stories either, however, Bruner’s definition still suggests that storytelling is a practice of expressing some pre- formed thematic or formal content or problem. Conversely, following recent reconceptualization of authorial intentionality as “built into the doing” (Herman 2008), of writing literature as thinking-in-action, we can interpret Beckett’s reticence as a way of expressing how his work is not an activity of explanatory problem- solving, but an exploratory problem- finding (see Bernini 2014). Some kind of scientific models, unlike philosophical arguments, can be closer to this heuristic, scaffolded practice of discovery that this book considers Beckett’s cognitive method to be.

As John Holland (2014) notes, in fact, models are not just explanatory or descriptive, but can also function as exploratory devices. In Holland’s words, “exploratory models start with a designated set of mechanisms, such as the various bonds between amino acids, with the objective of finding out what can happen when these mechanisms interact” (43; emphasis added). This book will argue that Beckett’s cognitive models, like exploratory models, select some specific mechanisms, laws, properties, dynamic in the human mind to see what happens in their interactions, notably when these interactions are lesioned in their networking with, and signaling to, each other. This openness to discovery, to the simulative consequences of this problem-finding operation, is what qualifies them, as the subtitle of this study anticipates, as exploratory narratives.

Beckett’s misgiving about the possibility of gaining knowledge and his renowned promotion of ignorance, however, might still seem to deny any kind of

attraction for science-like epistemic enterprises. This contrasts not just with Beckett’s interest in philosophy, but also with his extensive notes on sciences, from physics and geology to mathematics and psychology. Within Beckett studies, Chris Ackerley (2010) has masterfully charted Beckett’s interest in sciences, also pointing at the paradox of how Beckett’s sustained engagement with scientific ideas seems in conflict with his insistence on the impossibility of knowing physical and mental worlds. As Ackerley puts it, if one has to take seriously Beckett’s disbelief in epistemic endeavors, “any attempt [ . . . ] to saddle Beckett with a scientific temperament, let alone a scientific methodology, runs into an impasse generated by Beckett’s deep distrust of the rational process” (Ackerley 2010, 144). While taking into account Beckett’s wariness of rationality and epistemic formalization of outer and inner worlds, this book considers it as directed at a specific type of analytic, propositional knowledge, of the kind articulated by arguments aimed at solving problems. By contrast, a modeling view of his work as an exploratory trajectory into levels, layers, laws, properties and dynamics in cognition that are concealed by, and from, rational understanding might reconcile Beckett’s statement with his laboratorial research for a different kind of knowledge: an experiential, rather than propositional, knowledge which is unleashed by modeling manipulation, where the observer himself, as a human being endowed with a rationality that imprisons his own complexity, is the problem to be explored.

In its conclusion, this book will also argue that Beckett’s cognitive method might also be regarded as a resource to enhance cognitive scientific research into the mind. A good practice to be borrowed from cognitive sciences in introducing my own method, however, is to end this preface, as scientific papers do, on the limitations of my study. Given that this book is a cross-disciplinary, comparative look at Beckett’s modeling of cognition against contemporary cognitive models of the mind (and in relation also with contemporary narratological models), sometimes the reader might feel lost for a few pages in cognitive scientific theories and debates, without the secure anchoring of Beckett’s words and works. As much as this might be demanding, and limiting the readerly pleasure to literary scholars, I trust this is a necessary price to be paid in order to understand Beckett’s modeling at the same time as independently valid, and yet researching within similar coordinates of the contemporary science of mind.

Another, related limitation concerns the disproportion between the use of contemporary theories and frameworks compared with the relatively restricted engagement with thinkers contemporary to Beckett, and with Beckett’s archival material. Thankfully, both the historical and archival directions are very much covered by stellar scholarship in Beckett studies, even in relation to Beckett’s interest in the mind. In particular, it has to be mentioned the work done by a group of scholars (Ulrika Maude, Elizabeth

[ xiv ] Preface

Barry, and Laura Salisbury), who have been the ones inaugurating research on Beckett’s engagement with his coeval brain science, medicine, and psychiatry (with a series of projects between the University of Bristol, Warwick, Exeter and Birbeck College, and then with individual contributions and co-edited special issues; see, e.g., Barry 2008; Barry, Salisbury, and Maude 2016). As for a cognitive approach to Beckett’s manuscripts, Dirk Van Hulle (2014) and, after him, Olga Beloborodova (2015) have initiated what is a very exciting avenue of research (preceded by, and building on, the quite epochal, still ongoing, digitalization of Beckett’s manuscripts in the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project, which helped me discover the two doodles reproduced in the last chapter). Hopefully, some connections between the theoretical thesis advanced in this book and historical or archival dimensions can be found in the future.

A further limitation of this study is its speculative nature. If placed against a recent call by Matthew Feldman (2014), within Beckett studies, to restrict criticism to what can be, in Popper’s terms, “falsifiable” (i.e., based exclusively on evidences and theses that can be empirically proven wrong), this book would likely not pass the test. The account set forth in this book has not the scope to reach greater “explanatory power” (Feldman 2014, 67), but it rather partakes in the exploratory nature of Beckett’s work it aims to theorize about. This said, whenever possible, theoretical hypotheses have always been presented alongside Beckett’s own reflections on aesthetics, poetics, and cognition. This book was lucky enough to be born after the monumental, game- changing publication of the four volumes of Beckett’s letters, and these documents proved key sources to be scouted while writing this study.

A final remark, which more than a limitation is a courteous apology to the more sensitive readers, concerns the quite substantial introduction of new conceptual coinages in the form of neologisms. Without denying, as a reader, a flair for such devious practice, probably rooted in youthful encounters with the pathological jargon of continental structuralism, I think it might become a necessity when doing interdisciplinary theoretical work. Interdisciplinarity requires terminological negotiations, which certainly have to start by making clear how a specific term is used by a specific field. In order to turn this negotiation into a plastic, mutually constraining, conceptually creative convergence of models (that this book will advocate for as a theoretical work of co- modeling), however, something has to emerge beyond the existent terminological palette. These coinages are to some extent intended to be exploratory placeholders that hopefully can be further manipulated by a next generation of travelers within Beckett’s cognitive territories.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The paratextual threshold of acknowledgments feels, for a book that had quite a long gestation, as one of the hypnagogic, almost hallucinatory states we find in Beckett’s storyworlds. Shadows of significant memories surface in random order and one almost surrenders to the impossibility of giving justice (let alone a chronological ordering) to all the entities—either real, fictional, or imaginary— that helped me think this book from inception to completion. Words fail, Beckett knew, when time prevails. A holistic sense of gratitude is paired with the feeling of being just one of the characters in this story.

In the narratological community, the greater debt of gratitude goes to H. Porter Abbott: his sustained trust, exploratory drive, narratological bottega, and subsequent friendship have been of immeasurable importance to me. God reward you little master. I also want to thank Richard Walsh (and his Interdisciplinary Centre for Narrative Studies at York), and brotherly gratitude goes to my second-generation cognitive literary friends: Lars Bernaerts, Marco Caracciolo, Karin Kukkonen, and Merja Polvinen. It feels like we grew together in this growing field. Still in the cognitive humanities, I want to thank Peter Garratt (who established the Cognitive Futures in the Humanities network the same year I moved to the UK, which made me feel I landed in the right place), Alan Palmer, Paul Armstrong, Miranda Anderson (and philosopher of mind Michael Wheeler in her “History of Distributed Cognition” project), Emily Troscianko, and Anežka Kuzmičová. As for cognitive literary institutions, I want to acknowledge the talented leading cohort (Kay Young, Julie Carlson, Aranye Fradenburg, Sowon Park) of the Literature and Mind center at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for inviting over our second-generation group in 2017, and for all the collaborations and exchanges that followed.

Beckett scholars seem to share the same rigor, kindness, causticity, and obsessive dedication with the author they study. I have learned a great deal from working or discussing with Ulrika Maude, Matthew Feldman, Mark Nixon, Dirk Van Hulle, Elizabeth Barry, Laura Salisbury, Shane Weller, Arthur Rose, David Tucker, Nicholas Johnson and from witnessing the philological and

acoustic sensitivity of Jonathan Heron and Peter Marinker in action (Peter’s voice has now permanently crossed into my experience of Beckett’s narratives). I also want to thank Stanley Gontarski for his permission to reproduce an image of his direction of What Where. The doodles in chapter 4 are reproduced by kind permission of the Estate of Samuel Beckett, care of Rosica Colin Limited, London.

At Durham University, I want to thank my colleagues in the English Department, and the team members of the “Hearing the Voice” Wellcome Trust project (2012–2021). I am particularly indebted to Patricia Waugh, for her glaring intelligence and mentoring friendship, and a multilevel recognition goes to Angela Woods, masterful “producer” of knowledge, for modulating ideas and equalizing people like channels in a large interdisciplinary console. This book also benefited greatly from discussing and working directly with cognitive scientists interested in narrative and narrative theory. I have been in close contact with the experimental wisdom of Ben Alderson-Day, with whom I have long debated tools and methods, like mechanics tweaking interdisciplinary bridges. Charles Fernyhough and I talked aloud about his model of inner speech, and he has been a proactive supporter of cognitive literary approaches. Thanks also to Mary Robson, who always pushed the project to new levels of generative entanglement, humanity, and orbital collisions.

Other scholars in Durham I have to thank are the directors of the Institute for Medical Humanities, Jane Macnaughton and Corinne Saunders, and past interdisciplinary members of the institute: Felicity Callard, Felicity Deamer, Rebecca Doggwiler (who patiently helped with the diagram in chapter 2), John Foxwell, Joel Krueger, and Sam Wilkinson. Outwith and exceeding academic circles, creative friends and professional dreamers fed my mind with inputs throughout these writing years: I have to mention Antonio Bigini, Alessandro Carroli, Paolo Erani, Guido Furci (University of Paris III– Sorbonne Nouvelle), Roberto Laghi, Enrico Liverani, Luca Magi, Francesco Neri, Matteo Ossani, Davide Papotti (University of Parma), Stefano Sartoni, and Francesco Valtieri. This book, and my life, would have not been the same without these teammates and friends.

The research beyond this study started with a postdoctoral fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh, under the trusting guardianship of its director, Susan Manning. The bulk of the work has been conducted at Durham University, first through a Marie Curie Co-Fund Junior Research Fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Studies and then with a Wellcome Trust postdoctoral fellowship in English Studies as a member of the “Hearing the Voice” project (grant WT098455 and WT108720). I thank the funding bodies for their support. Earlier versions of parts of some chapters (1.4, 3.1, 3.2, 4.2, 4.3) have previously appeared

[ xviii ] Acknowledgments

in Samuel Beckett Today/ Aujourd’hui, European Journal of Modern Literature, Frontiers of Narrative Studies. The publishers are gratefully acknowledged.

I am beholden to the three anonymous reviewers at OUP, who all offered insightful suggestions to the book proposal, and particularly to the anonymous reader of the entire manuscript, whose detailed comments corrected and enhanced its final shape. I take full responsibility for stubbornly preserving some linguistic torsions in its published version. I also would like to thank all those at Oxford University Press who looked after each stage of the book, in particular to Hallie Stebbins and Meredith Keffer for their understanding guidance through the copyediting and production processes. Copyediting was expertly conducted by Rick Delaney, and the index was prepared by Colleen Dunham, with the generous support of the English Department at Durham University.

I am thankful to my mother, Maurizia, for being a model of work ethics, for her constant support and inspiring stories of will and mobility, which taught me that you do not have to end where you started; and to my sister, Laura, for her friendship and for having brought psychological know-how (and the brightening Tommaso) to our family matters. The more intimate debt is to my future wife Federica, whose contagious imaginarium, experimental zest, and luminous halo have survived intact a chase of many years and countries. We made it. This book is dedicated to the memory of my father, Nicola, and of my best friend and sister by adoption, Ilaria. I will never have done revolving it all.

CHAPTER 1

Modeling the Apparent Self

Waking up begins with saying am and now. That which has awoken then lies for a while staring up at the ceiling and down into itself until it has recognized I, and therefrom deduced I am, I am now Here comes next, and is at least negatively reassuring; because here, this morning, is where it has expected to find itself: what’s called at home. Isherwood, [1964], 2010, 1

Contemporary scientific debate about the self can be qualified as an arena opened by a Cartesian orphanage. For long, as Gallagher and Shear note, Descartes’ “thesis that self is a single, simple, continuing, and unproblematically accessible mental substance resonated with common sense, and quickly came to dominate European thought” (1997, 399). After radical blows inflicted by empiricist or pragmatist thinkers like David Hume or William James, cognitive science is today largely rejecting Descartes’ view of the self as an internal and unified “thing” or substance. The growing amount of books by foremost philosophers of mind (Metzinger 2009) and neuroscientists (Hood 2012; Gazzaniga 2012) on the so- called “illusion of self” (Albahari 2006; see also Siderits et al. 2011) is the most tangible sign of how the current dominating theory is rather that we are not who we feel or think we are. If hardly anybody questions that our common phenomenological sense of being or having a self is real, the illusion would reside precisely in a misalignment between this phenomenological feeling and a different underlying ontology. This debate has led to a vital new “tradition of disagreements” (Gallagher 2012, 122–127), with a variety of competing or complementing explanatory models attempting to account for what is illusory about the self, for what is not, and for how this illusion is generated.

These models will be progressively reviewed throughout this chapter, as the theoretical ground against which to understand and analyze Beckett’s own

Beckett and the Cognitive Method. Marco Bernini, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190664350.003.0001

variety of modeling solutions in exploring what he also called, in a letter to George Duthuit on July 27, 1948, “the illusion of the human and the fully realised” (BL II, 86). Neither cognitive sciences nor Beckett use the qualification of the self as an illusion merely as a metaphorical descriptor. It is rather aimed at capturing something real about how the (feeling of a) self actually might be, as the narrator of Beckett’s first novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women (written in 1931–1932; published posthumously in 1992), calls it, one of the “fake integrities” (D, 28) our mind conjures up. This is why, as a preliminary move, it might be worth looking into the less mysterious working of optical illusions, to see what kind of cognitive processes they might share with the construction or emergence of the (feeling of a) self. To introduce contemporary models of how the illusion of our human self is fully realized, I will therefore start by comparing this experience with the scientific study of an optical illusion inaugurated by the father of the Gestalt School of psychology, Max Wertheimer, whose work Beckett came into contact with in his formative years (see Salisbury 2008). To overcome the limitation of writing as a non-optical medium, and to honor some of Beckett’s narrative openings (All Strange Away, Imagination Dead Imagine, Company), let us thus begin with a conative prompter to imagination.

1.1. AWAKENING IN THE BIOSCOPE: WERTHEIMER’S LAW, PREDICTIVE SELF, AND CHRONOTOPIC GROUNDLESSNESS

Imagine you are in a dark room, facing two light bulbs, placed in close proximity. Suddenly, one bulb flashes, followed by the other, within an interval of 60 milliseconds. Rather than seeing two separate lights beaming in sequence, your mind would perceive a single bulb, moving in a trajectory from the first to the second position. This phenomenon is known, since its seminal study by Wertheimer, as “perceived” or “apparent motion” ([1912] 2012). Its relevance has nowadays been extended beyond visual cognition, and it is regarded by contemporary cognitive science as a landmark illustration of our mind’s broader capacity of making sense of unfolding events through “interpolation based on expectations” (Radvansky and Zacks 2014, 109). An increasingly popular view of the mind (variously referred to as “predictive processing framework” or “predictive coding”; see Clark 2015),1 in fact, suggests that

1. This model of the mind and/or brain (the distinction is sometimes problematically left implicit) as a predictive machinery has rapidly conquered the mainstream of contemporary cognitive sciences. Given the gamut of target phenomena to which it has been applied, and the variety of explanatory levels it aims to account for (from physicalist to phenomenological), it is often characterized in terms of a research “framework” (to get a sense of its multipronged ambition, see Metzinger and Wiese 2017). Promising directions are testing this predictive view of cognition not only on common

apparent motion is one of the many examples uncovering how active anticipation and interpolation are bearing walls of our cognitive architecture. Building on past experiences and perceptual habits, our mind actively predicts, and therefore perceives, a unified agent instead of two separate stimuli (see Clark 2015, 44, 86). At the neurological level, this hypothesis has been supported by data showing how, in apparent motion, the “virtual cortex actively anticipates the input and such anticipation allows predictable stimuli to be processed with less neural activation” (Alink et al. 2010, 2965).

The fact that active anticipations occur at the brain level (before and, if successful, mostly without conscious awareness) further explains how apparent motion can be a perception, and not a postdictive rationalization or conscious inference. Wertheimer anticipated this point in his original study, noting how unified apparent motion is therefore “different from ‘I see a; I see b;’ I confidently assert they must actually be the same” ([1912] 2012, 24). The illusion of unity of a single bulb is rather experienced as identity and continuity which are “phenomenal,” as Wertheimer put it, “absolutely different from a ‘now here’, ‘now there’ [ . . . ], different from ‘there is another one like him; it must be the same thing’ ” (24). In short, our mind actively creates an experience of unity from, and concealing, the discontinuous plurality of bulbs underlying this event. As many optical illusions, apparent motion is a fragile trickery though. If the interval between the flashes is slightly altered, the real presence of multiple bulbs is revealed, either as simultaneity (if decreased below 30 milliseconds) or a succession (if increased above 200 milliseconds; see Steinman et al. 2000).

Active anticipations, bridging gaps in perception, can be partly responsible for the emergence of what I will term, after Wertheimer, the apparent self. To understand how, now imagine you are waking up after a quiet, sober, and uneventful night. Rather than feeling a different person from the night before, your mind will tell you that you are the same self as the previous day, only a few hours older. The endurance of our subjectivity between bouts of sleep is another privileged example of the science of mind. As with apparent motion, it is considered as a local case to debate a much more global dynamics in our cognitive life: here the unitary agent that we call our self, and its very existence, subsistence, and fragility (e.g., Thompson 2014, 236; Bayne 2010, 281–289; Flanagan 1992, 157). Awakenings, in fact, are daily reminders of what has been labelled the “bridge problem” (Dainton 2008), which consists in explaining how the self can persist or, as some philosophers have qualified this transition in more frightened terms, “survive” (Parfit 1971, Lewis 1976) as a unified entity across phenomenal gaps. Is our self the bridge that is, as in Kafka’s short story (“The Bridge,” [1931] 2005), casted over the silent obscure

or wakeful perceptions, but also on hallucinations (Wilkinson 2014) and even dreams (Bucci and Grasso 2017). We will go back again to predictive processing in chapter 4.

ravines of unconscious gaps (and, as Kafka puts it, “no bridge, once spanned, can cease to be a bridge,” 411)? Or is the awakening self the illusory outcome of some bridging cognitive processes, akin to the ones operating in apparent motion? In his Principles of Psychology ([1890] 2007), William James already drew attention to how “sleep, fainting, coma, epilepsy, and other ‘unconscious’ conditions are apt to break upon and occupy large durations of what we nevertheless consider the mental history of a single man” (199; emphasis added). Our consciousness switches off, then on again, in a more or less close temporal and spatial proximity, then somehow mysteriously “the two ends join each other smoothly over the gap” (199). As a result, instead of perceiving two discrete selves in a succession or simultaneously co-present, a single self appears as a continuous agent or substance arching between phenomenal gaps.

As in apparent motion, our self (re)emerges across the gaps as an experienced reconnection, characterized by the felt perception of an unbroken sameness. In normal conditions, as Antonio Damasio (2010) notes, connectedness is in fact the main feature in awakenings, insofar as “the myriad contents displayed in my mind, regardless of how vivid or well ordered, connected with me, the proprietor of my mind, through invisible strings that brought those contents together in the forward-moving feast we call our self; and, no less important, the fact the connection was felt” (4). A further similarity with apparent motion, however, is that altered environmental conditions or an altered speed in the awakening process might hamper this forward-moving anticipatory feast. Marcel Proust, on whom a young Beckett wrote a study in 1931 that will guide us throughout this first section, is probably the most notorious collector of these altered awakenings. In the first volume of his À la Recherche du Temps Perdu ([1913] 2005), for instance, he describes how, when our awakening predictive machinery gets clogged somehow, the feeling of not knowing where we are pairs with an uncertainty regarding who we are, so that “when I awoke in the middle of the night, not knowing where I was, I could not even be sure at first who I was; . . . [B]ut then the memory—not yet of the place in which I was, but of various other places where I had lived and might now very possibly be— would come like a rope let down from heaven to draw me up out of the abyss of not-being, from which I could never have escaped by myself” (4; emphasis added). In this passage, Proust finely renders how the predictive machinery is not a disembodied repertoire of information, but it rather recruits a tight mixture of past embodied sensorimotor interactions in a particular time and space. Proust foregrounds how we are a collection of enacted junctures of space and time, or what the Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin called a “chronotope” (1981). What Bakhtin said about “the image of man in literature” (85) being structurally chronotopic, therefore, seems true also for our self in the real world. This is why, as Proust describes it, when the predictive machinery hesitates between possible chronotopical anchorings or selves, our very existence seems suspended.

This is the kind of suspension that another strand in the science of mind, which stresses the enactive component of cognition, has characterized as an “evocation of groundlessness” (Varela, Thompson, and Rorsch 1993, 217). According to this complementing model, our self is just a complex (see chapter 5), incremental result of a series of sensory-motor engagements or, in the enactivist terms, “structural couplings” (217) with different times and spaces. There is no enduring substance or self behind these coupled interactions with the world, and “we could discern no subjective ground, no permanent and abiding ego- self. When we tried to find the objective ground that we thought must still be present, we found a world enacted by our history of structural couplings” (217; emphasis added). This view makes James’ image of our self as a mental history of a single man more embodied, which also means that it makes it more sensitive, as Proust describes it, to environmental variations such as sleeping in a new room or changes in our usual bedroom (see Bernini 2020). What altered awakenings evoke, by keeping the organism suspended between unconscious gaps, is therefore an ontological vertigo that we can describe as chronotopic groundlessness: the feeling of our self disappearing if uncoupled from the geolocalizing convergence of a particular space and time.

Beckett, as and after Proust, is among the many literary writers2 who have been interested in hypnopompic moments precisely as telling cognitive cliffhangers, where our subjectivity betrays its thin wires. The beginning of A Single Man ([1964] 2010) by Christopher Isherwood prefacing this chapter, for instance, carefully renders how, for the mental history of a single man to be restored, the higher biographical work of memory has to recruit and cooperate with lower pre-reflective embodied feelings in order to come, as Proust says, like a rope to rescue us. Isherwood’s beginning strictly recalls some of Beckett’s own narrative openings, with the exception that Beckett’s characters never fully end up feeling at home again (as the protagonist of The Expelled [1946–1947] ironically remarks, “You can hardly have a home address under these circumstances, it’s inevitable,” EX, 10). If Beckett sometimes presents a character actually waking up (notably, the drowsy narrating character of Malone Dies (1951), who in his bed often “fear I must have fallen asleep again,” MD, 202), more frequently he transforms the conventional narrative limen of

2. In a perceptive, compact study on the representation of hypnagogic and hypnopompic experiences in literature, Peter Schwenger (2012) has gathered a rich repertoire of writers, mostly from the modern period, focusing on dozing or awakening states. Here Schwenger also rightly points at the inherent liminality of writing and reading states, arguing that “[t]o characterize the reading of a literary text as either a fully conscious and rational activity or an immersion into dream is at either extreme to distort the experience. Literature is liminal; and this is so for both the reader and the writer” (xii). Beckett’s interest in liminal awakenings, in this sense, can be seen also as experientially rooted in his experience as a writer; in addition, the functioning of his narrative models partly relies on the liminality of readerly states (on which see also chapter 4).