Introducing the beaver

1.1 A buck-toothed wonder

Early written descriptions of beavers (Castor spp.) are not kind. The openings of Lewis Henry (Morgan)’s iconic writings in 1868, introducing the beaver to a European and colonial American audience, clearly place the beaver at the lower end of mammalian evolution. With descriptions that include ‘a coarse vegetable feeder’ whose ‘clumsy proportions render him slow’, ‘inferior to the carnivorous and even the herbivorous animals’ when comparing to both other land and water mammals, seem somewhat harsh. However, he could not help but be impressed by the beaver’s architectural skills, dedicating most of his book to these. Again perhaps somewhat unfairly, the American naturalist and historian Earl Hilfiker (1991) described the beaver’s appearance as ‘definitely not impressive. It is the things he does rather than his appearance that make him one of the most widely recognized forms of North American wildlife’. More recently, Frances (Backhouse)’s book Once They Were Hats (2015) opens with discussing the beaver’s image problem: ‘a chubby rodent with goofy buckteeth and a tail that looks like it was run over by a tractor tire’. She goes on to elegantly argue for the beaver’s rightful place in history, their incredible influences on our ecosystems, and why we should respect this fascinating animal with its uniquely adapted biology and natural history. Saying that, if the reports of some of the objects found in beaver constructions are to be believed, from lengths of pipe, steals from nearby firewood stores, fence posts, beer bottles, drinks cans, tyres, and even a prosthetic leg (Goldfarb, 2018), beavers are also practical recyclers with potentially a great sense of humour!

Beavers are unique, oversized, semi-aquatic rodents with distinctive features such as their flat scaly tail, webbed hind feet, prominent teeth, and luxurious fur (Figure 1.1), and they exhibit specialized behaviours such as damming and tree felling that can transform landscapes. Because of such adaptations, few species, bar humans, can so readily modify their surrounding environments if left to their own devices.

Beavers have a long history of being utilized and eradicated by humans—for food, various body parts, and of course their highly valued fur (see Chapter 2) but also indirectly with their activities providing habitats for numerous species, thereby providing foraging opportunities and ecological benefits such as water storage in times of drought (see Chapter 9). They are a highly adaptable species and can modify many types of natural, cultivated (Schwab et al., 1994), and urban habitats (Pachinger and Hulik, 1999) to suit their needs. Although beavers can also establish in brackish water (Pasternack et al., 2000), especially at higher population density, they are typically a freshwater species, occupying a wide range of freshwater systems including ponds, streams, marshes, rivers, lakes, and even agricultural drainage systems. They thrive in areas stretching from sea level (0 m a.s.l.) to mountain areas (upto 3,500 m a.s.l., including the Rocky Mountains, Colorado), though preferring low-gradient watercourses (Novak, 1987; Osmundson and Buskirk, 1993).

Box 1.1 describes the classification of beavers (Castor fiber and C. canadensis). Both species play a crucial role in wetland ecology and species biodiversity and can provide important ecosystem services such as habitat creation and water management. This is challenging in modern, often heavily modified landscapes. The history of the beaver represents CHAPTER 1

Box 1.1 Beaver classification

The family Castoridae is not closely related to any modern rodent group. They are represented today by only two extant species in the once-larger Castorimorpha branch.

Beaver classification is as follows:

Class: Mammalia

Order: Rodentia

Family: Castoridae

Genus: Castor

Species: Castor fiber Linnaeus, 1758 (Eurasian beaver)

Castor canadensis Kuhl, 1820 (North American beaver)

important lessons in conservation, as both species were on the verge of extinction solely through human activities. These biodiversity and ecological services benefit that beaver activities can generate are only now being recognized in more modern times (Rosell et al., 2005; Stringer and Gaywood, 2016). Their restoration has offered exciting opportunities for habitat and biodiversity restoration if

we are prepared to tolerate, accept and even embrace their activities.

1.2 All in the name

The formal scientific name, Latin ‘castor’ and Greek ‘kastor’, is thought to originate from the Sanskrit ‘kasturi’ meaning musk, though it has also been suggested that the Greeks called it Castor from gastro, the stomach, given their rounded appearance (Martin, 1892). When formally naming the beaver (1758), recognizing only one species at the time, Carl Linnaeus basically named it ‘beaver beaver’, as the genus name ‘fiber’ means beaver in Latin (Poliquin, 2015). Kuhl formally described and named the North American beaver in 1820, over two centuries after some of the first fur trading posts were established in Canada (Martin, 1892). The genus name ‘canadensis’ represents the North American geographic range (Long, 2000).

The Old Norse for beaver was ‘bjorr’, leading to ‘bjur’, ‘bur’, and ‘björ’ in Old Scandinavian. In today’s more modern languages, the Norwegian ‘bever’, Swedish ‘bäver’ (first appearing in Swedish texts from the sixteenth century), Danish ‘bæver’, Dutch ‘bever’, and German ‘biber’ are especially

Figure 1.1 Beavers are unique semi-aquatic rodents, highly social in family groups, living in actively defended territories against other beaver families. (Photo supplied courtesy of Michael Runtz.)

similar. The Old English term ‘beofor’ has at various points also been spelt ‘befor’, ‘byfor’, ‘befer’, and ‘bever’—all presumed to have their origins in the Old Teutonic term ‘bebru’, a general reference to a brown animal. Yet another similar word is ‘bhebhrú’ meaning brown water animal in Old Aryan (Long, 2000). During the Middle Ages in Britain, ‘bever’ or ‘bevor’ were words used to describe a drink or snack between meals, leading to the word beverage. The verb to ‘bever’ was to tremble or shake. At other times, ‘beaver’ or ‘bever’ was a type of face guard on military helmets and even undergrowth associated with hedges was called ‘beaver’ or ‘beever’ (Long, 2000).

1.3 A robust rodent

Beavers are often described as a ‘robust’ rodent. They are streamlined and thought of as more agile in the water, though are sizeable, chunky animals especially when viewed on land. Both species are remarkably similar in morphology, with body shapes often described as teardrop with short, stumpy limbs. Beaver morphology reflects their adaptations to a semi-aquatic lifestyle (see Chapter 3). Their large webbed hind feet are specialized for swimming, providing forward thrust to quietly propel them through the water, along with a unique tail with a developed caudal muscle attachment to the vertebrae. Their tail is dorsal-ventrally flattened, pretty much hairless, with skin patterning often described as scaly in appearance. Beaver tails (see more in Chapter 3) are fairly large affairs, though slight variability is evident across adults and according to body condition. Beavers are dominantly brown in coloration, with dark-grey tails, for example accounting for 91.8% of animal observed in Karelia, Russia (Danilov et al., 2011a), though pelage colour can range from almost blonde to reddish-brown to black, with even white individuals known (Baker and Hill, 2003). Very light-coloured beavers have been recorded, but albinism is rare (Novak, 1987). Native Americans attached significant value to the skins of white beavers, which were often made into medicine bags (Martin, 1892). Partial albinism or ‘spotted’ beavers have been recorded in

North America and Russia, with white appearing as irregular patches especially on the stomach and hind feet (Lovallo and Suzuki, 1993). Isolated beaver populations in Central Asia have also been observed with white spotting on their ventral sides (Busher, 2016). Completely black beavers are more common than white or spotted variations, and these often fetched the highest prices in early fur exploitation in Canada (Martin, 1892). Up until the 1970s it was reported that all beavers residing in the Luga watershed, Leningrad region, were composed of only black individuals (Danilov and Kan'shiev, 1983). Out of 350 North American beavers trapped in Karelia and the Leningrad region, only two were nearly black, with the rest varying in coloration from light- to dark-brown (Danilov and Kan'shiev, 1983; Kanshiev, 1998). Export lists of beaver pelts from sixteenth-century Stockholm note colour variations, with black pelts being the most expensive, suggesting reintroductions from Norway may have lost some of this colour variation during genetic bottlenecking (G. Hartman, pers. comm.). Brown pelage is therefore presumed to be the dominant genetic trait for both species, given the scarcity of other colours and brown offspring being born to black parents (Danilov and Kan'shiev, 1983).

Typical body dimensions vary due to a range of factors, such as time of year and habitat quality, and age class should also be considered (Tables 1.1 and 1.2; Figure 1.2). Newborn kits tend to weigh between 380 and 620 g (mean 525 g in captive Eurasian beavers; Żurowski, 1977) and typically reach between 7 and 9 kg by the end of their first year (Ognev, 1947). Adults (≥ 2–3 years) on average weigh around 18 kg but can reach 26+ kg, though general body dimensions are less variable with age (Grinnell et al., 1937; Leege and Williams, 1967; Aleksiuk and Cowan, 1969; Parker et al., 2012). Mass is used to distinguish subadults (between ≥ 17 and ≤ 19.5 kg) and adults ≥ 3 years (≥ 19.5 kg) (Rosell et al., 2010). Rarer examples of Eurasian beavers weighing 29–35 kg have been trapped in Russia, including a 36-kg female (Yazan, 1964; Solov’yov, 1973; Danilov et al., 2011a). North American adults weighing between 24 and 28 kg are common; more rarely maximum body weights of 37–39 kg have been recorded in North

Parameter

Body weight 17.8 kg

Body length 80.5 cm

Tail length 26.3–30 cm

Tail width 13cm

Danilov et al. (2011a) 17.2 kg

Danilov et al. (2011a)

Danilov et al. (2011a) 25.8–32.5 cm

Danilov et al. (2011a) 9–20 cm

Jenkins and Busher (1979); Baker and Hill (2003); Danilov et al. (2011a) (North American in Karelia)

Jenkins and Busher (1979); Baker and Hill (2003); Danilov et al. (2011a)

Grinnell et al. (1937); Davis (1940); Osborn (1953); Jenkins and Busher (1979); Baker and Hill (2003) Danilov et al. (2011a);

Grinnell et al. (1937); Davis (1940); Osborn (1953); Jenkins and Busher (1979); Baker and Hill (2003); Danilov et al. (2011a)

Table 1.2 Age class body dimension breakdown of the Norwegian beaver (Rosell and Pedersen, 1999).

Age class Body length (cm)

Tail length (cm)

Tail width (middle point) (cm)

One-year olds 70–80 17–23 5–8

Two-year olds 90–100 23–27 8–10

Adult 100–110 27–31 10–12

1.4 The two beavers

Figure 1.2 Body weight with beaver age. (Reprinted from Campbell, R. 2010. Demography and life history of the Eurasian beaver Castor fiber. PhD thesis, University of Oxford.)

America (Grinnell et al., 1937; Schorger, 1953) and even a 44-kg individual (Seaton-Thomson, 1909).

Adult body lengths can vary, and though there may be inconsistences with measuring methods, 100–120 cm has been recorded in North American beavers (Grinnell et al., 1937; Osborn, 1953; Jenkins and Busher, 1979).

The collective term ‘beavers’ recognizes that there are two species of beavers alive today. Although people have been quite challenged to physically distinguish between them, genetic evidence clearly determines the Eurasian beaver (C. fiber) from the North American or Canadian beaver (C. canadensis). Both modern species are incredibly similar in appearance and behaviour which can make them hard to distinguish in the field (Rosell et al., 2005; Danilov et al., 2011a). Whilst some differences in skull morphology were first described by Cuvier (1825), historically most zoologists considered that all beavers were either one species or two subspecies (Morgan, 1868). It was not until differences in the number of chromosomes determined fairly late on the existence of the two distinct species: the Eurasian beaver has 48 pairs of chromosomes, whereas the North American has 40 pairs (Lavrov and Orlov, 1973), which clearly distinguishes them as separate species. Captive experiments investigating whether these would interbreed took place, but although copulations were recorded, no hybrid offspring resulted (Lavrov and Orlov, 1973). More recent genetic analysis in developing a rapid DNA assay between the two beaver species determined that SNP positions 1971 and 2473 in the 16-s mitochondrial gene are fixed for nucleotides C/A in Eurasian beavers and G/T in North American beavers, respectively (McEwing et al., 2014). These fixed differences are ideal for species identification purposes and could be used to develop a quick field test.

Table 1.1 Reported average adult body dimensions of the two species (note 2-year olds are included, thus lowering the mean mass).

To the experienced observer, subtle differences in pelage colouring (such as more buff-coloured cheeks and rarity of black individuals in North American beavers) and differences in tail shape (generally slightly rounded, more oval shaped in North American whereas straighter edged, parallel sides of the Eurasian have been noted) have been reported, though setting consistent defining species standards can be complicated (Danilov, 1995). Internal differences in skull morphology are evident; at least seven differences have been reported, including nasal bone structure, depression of basioccipital, and shape of nostril and

foramen magnum (Miller, 1912; Ognev, 1947; Figure 1.3a and b). These of course cannot be used in field assessments, and many of these physical differences are only relevant on post mortem examination. One curious and seemingly reliable difference appears to be the colour and viscosity of their anal gland secretions (AGS) (Figure 1.4).

Examination of these is a quick and reliable method to determine the sex of a beaver, as external sexually dimorphic features are often lacking across both species (Rosell and Sun, 1999).

Many authors have investigated and postulated over dissimilarities between the species (Table 1.3)

(a)

(b)

Figure 1.3a and b Differences in skull morphology exist between the two beaver species, the Eurasian (a, on the left) North American beaver (b, on the right), note the more triangular rostrum in the Eurasian. (Photos supplied courtesy of Michael Runtz.)

Figure 1.4 Anal gland secretion (AGS) colour and viscosity vary but can be reliably used to identify species and sexes. (Photo supplied courtesy of Frank Rosell.)

Table 1.3 Main reported differences between the two extant beaver species (Miller, 1912; Ognev, 1947; Lavrov, 1980; Lavrov, 1983; Rosell and Sun, 1999; Rosell et al., 2005; Danilov et al., 2011a; Müller-Schwarze, 2011).

Feature Eurasian

Genetic

Chromosome number

Cranium

Skull volume

Nasal opening

Nasal bones

Depression between auditory bullae in the lower basioccipital region

Pterygoid process

Least depth of rostrum behind the incisors

Occipital foramen

Foramen magnum

Cranium width in front postorbital processes

Mandible

Mandible angular process

Coronoid process

Depression between coronoid and angular processes

Internal

Uterus masculinus

Anal glands

Anal gland secretions

Tail vertebrae

Crus bones

External

Fur

Tail shape

Vertical posture

Life history

Sexual maturity

Behavioural

Dam building

Lodges

Scent mounds

48

Smaller

Triangular

Extend beyond nasal processes of premaxillae

Broad and rounded

Large, 4–6 mm wide

Greater than distance from gnathion to end of infraorbital foramen

Vertically elongated

Rounded

Nearly equals greatest breadth of nasal bones

Elongately rounded, moderately massive

Strongly bent backwards

Prominent

Present and more consistently identifiable

Larger volume

Female: greyish-white, paste-like

Male: yellow to light-brownish, more fluid

Narrower, less developed processes

Shorter

Longer hollow medulla

Parallel at midpoint, width 47% of length

Assumed less often due to crus bone morphology

Later typical

Similar

Bank lodges numerous

Smaller

North American

40

Larger

Quadrangular, slightly shorter below than above

Do not extend beyond nasal processes of premaxillae

Ovate

Thin, < 2 mm wide

Nearly equal to distance from gnathion to end of infraorbital foramen

Horizontally elongated

Triangular

Greater than greatest breadth of nasal bones

Short, with rounded edge and very massive

Sharpened, bent backwards

Shallow

Not always present and highly variable in form and shape

Smaller volume

Female: whitish to light-yellow, runny

Male: brown and viscous, darker than Eurasian

Broader, more developed processes. Deeply bifurcated laminae

Longer

Shorter hollow medulla

Broader across midpoint, width 56% of length

Assumed more often due to longer crus bones

Earlier possible

Similar—greater falsely reported

Free-standing lodges numerous

Some ‘giant’ mounds recorded

and whether these permit one to have a competitive edge over the other, but general conclusions appear unified (for example, Danilov, 1995; Dewas et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2012; Frosch et al., 2014). Over the years, various studies have reported ecological and life history trait differences. Such comparison studies are particularly relevant where both species are meeting along several fronts, such as in parts of Finland and Russia. For example, studies of adjacent populations of both species living in north-western Russia and Ruusila stated that North American beavers built more dams and stick-type lodges (Danilov and Kan'shiev, 1983), other North American biologists claiming at one point that the greater building activities of North American beavers assisted in giving them a competitive edge (Hilfiker, 1991; MüllerSchwarze, 2011). More recent investigations have reviewed a wide range of ecological features across numerous populations of both species and not found any significant differences, including diet, habitat use, and construction types (Danilov et al., 2011b; Parker et al., 2012). The latest conclusions are that both species build the equivalent frequency and degree of dams and lodges under the same habitat conditions in south Karelia (Danilov and Fyodorov, 2015). Therefore, the niche overlap of both beavers is considered as virtually complete unless further information from sympatric populations comes to light (Parker et al., 2012).

Typically, North American beavers were often presumed to be bigger, raising concerns that this may give them a competitive advantage in body size and aggression in territorial disputes, therefore enabling them to outcompete the native Eurasian. However, body length and masses are highly comparable (Danilov et al., 2011a). It has long been believed that the North American beaver becomes sexually mature faster and has higher fecundity rates (Müller-Schwarze, 2011), with the combined effect of higher fetus numbers (C. c. ~4.0, C. f. ~2.5) and mean litter sizes (C. c. 3.2–4.7, C. f. 1.9–3.1). Logically this leads to differences in mean family group sizes (C. c. 5.2 ± 1.4, C. f. 3.8 ± 1.0) (see Chapter 6). This was thought to give North American beavers a competitive edge and

to explain their more rapid population expansion compared to Eurasian beavers in Finland (Nummi, 2001). However, this is contested by other researchers; moreover, as the two species meet in various parts of Finland and Russia, there are no clear winners and the picture is more complex (see Chapter 2). Actual differences in age of sexual maturity may not be accurately distinguished but rather confounded with data on first age at reproduction, in turn more influenced by population density as opposed to fundamental species differences in reproductive biology. It is therefore not clear if the two beaver species would eventually coexist or be excluded by the other (Petrosyan et al., 2019). Interestingly, several studies report immunophysiological differences between the species, also demonstrated where they both occupy the same habitat. North American beavers appear to have a higher susceptibility to tularaemia and to be a significant reservoir (Mörner, 1992), whereas the Eurasian beaver is reported only sporadically a host (Girling et al., 2019). During tularaemia outbreaks among wild rodents in Voronezh province, Russia, between 1943 and 1945, over half of the North American beavers held at the research centre died, whilst local Eurasian beavers held at the same facility were unaffected (Avrorov and Borisov, 1947).

1.5 Fossil beavers

All rodents share a common ancestor around 57–76 million years ago (myr), with the early beaver-like animals diverging from the scaly-tailed squirrel Anomalurus and first appearing around 54 myr (Horn et al., 2011). Therefore, the animal we know today has an incredibly long evolutionary history, though questions still exist around its evolution and closest relatives, as rodent phylogenetic relationships are still difficult to decide (Korth, 1994; Horn et al., 2011). Today’s beavers are evolutionary distinct—the only remaining members of the once much larger and diverse family of Castoridae, which dates back nearly 40 myr. The diverse fossil taxa were thought to include up to 30 genera, with more than 100 species at one point (McKenna and

Bell, 1997; Korth and Samuels, 2015; Mörs et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017). In China alone at least ten species of extinct beaver spanning eight genera have been determined from sediments spanning the Early Oligocene to the Pleistocene (Yang et al., 2019), originating from a mouse-related clade, which contains several families including Anomaluridae (scaly-tailed squirrels), Geomyidae (burrowing rodents like gophers), Dipodidae (such as jumping mice), Heteromyidae (such as burrowing rodents, e.g., kangaroo rats), Muridae (true mice), and Pedetidae (springhares) (Huchon et al., 2002; Adkins et al., 2003; Huchon et al., 2007; BlangaKanfi et al., 2009). Some debate remains as to whether beavers are more closely related to the scaly-tailed squirrels (Horn et al., 2011) or the Geomyidae (Blanga-Kanfi et al., 2009). The extinct Eutypomyidae are proposed to be the closest related group to Castoridae (Wahlert, 1977). Castoridae varied greatly, from small burrowers around 1 kg in size such as Palaeocastor spp. found in the Late Oligocene and Early Miocene to the bear-sized giant beavers of the Pleistocene (Korth, 2001; Rybczynski, 2007).

The origin of the Castoridae, genus Agnotocastor (Stirton, 1935), is found in North America at the end of the Eocene (37 myr) representing species that could produce, store, and dispense castoreum (Korth, 2001; Rybczynski et al., 2010). These were also found in Asia and France (Hugueney and Escuillie, 1996) in the Oligocene, suggesting they originated in North America and then radiated out into Asia and wider Eurasia, but this remains debated (Horn et al., 2014). Fossil remains of Castoridae have been found in the Middle East from around the Lower Oligocene and Upper Miocene (Turnbull, 1975). Either way, this occurred via the Beringia isthmus. This was an Arctic land bridge, existing throughout most of the Cenozoic, and although subject to climatic change it enabled ‘faunal interchange’ and mammalian dispersal between Eurasia and North America (Beard and Dawson, 1999; Gladenkov et al., 2002). This is demonstrated by fossil beaver finds in the Yushe basin, China, which are characterized by long lineages of Dipoides, Trogontherium, and Sinocastor (considered a subgenus of Castor), the majority dating back to the Pliocene, with some Dipoides

species occurring in the Late Miocene (Xu et al., 2017). These early castorids then gave rise to the burrowing Palaeocastorinae (Martin, 1987; Hugueney and Escuillie, 1996; Korth, 2001; Korth and Rybczynski, 2003). The first animals closely related to beavers and often described as the direct ancestors of contemporary beavers of Eurasia are the genus Steneofiber (Geoffroy, 1803), appearing in the Late Oligocene (Hugeney, 1975; Lavrov, 1983; Savage and Russell, 1983). Though they were around the size of marmots (genus Marmota), they share morphological similarities, especially in molar structures (Lavrov, 1983). Fossil remains of a family found in France, presumed as ten individuals, were discovered in close proximity and displayed various teeth development, from worn adult teeth to erupting premolars, indicating family structure and breeding patterns parallel to extant beaver species (Hugueney and Escuillie, 1996). The genus Castor in Europe has been dated back to between 10 and 12 million years (Lavrov, 1983).

It is thought that up to 30 genera once existed up until the Miocene in Eurasia and up to the Late Pleistocene in the rest of the northern hemisphere (Korth, 2001; Rybczynski, 2007; Rook and Angelone, 2013), so that beavers in the past were much more diverse than today. The palaeocastorine beavers tend to refer to those fossorial beavers restricted to North America and represent an Early Oligocene–Miocene radiation (Stefen, 2014). Around 30 myr palaeocastorines diverged into approximately 15 species (Martin, 1987); this radiation was thought to be associated with a climatic shift, the appearance of more open, grass-dominated habitats, and burrowing adaptations (Strömberg, 2002; Samuels and Valkenburgh, 2009). Table 1.4 shows the approximate beaver timeline based on fossil finds.

It was not until the Early Miocene (24 myr) that the familiar traits of modern beavers—wood cutting and swimming—evolved (Rybczynski, 2007). Prior to this, ancestral beavers tended to be small burrowers (a bit larger that a prairie dog) and are thought to have originated from Palaeocastor in the Late Oligocene and Early Miocene (~25 myr) which were adapted to fossorial habits in more upland and arid habitats not associated with

Table 1.4 Approximate fossil beaver timeline (years ago) (Pilleri et al., 1983; Müller-Schwarze, 2011).

Period Pleistocene Tertiary

present

Key events Both extant species coexisted with giant forms

North America Castoroides ohioensis

Castor canadensis

Eurasia Castor fiber

Trogontherium

Castor arrives in North America, speciation of extant species

Dipoides

Amblycastor

Castor

Eucastor

Trogontherium

Steneofiber

Castor spp.

Wood cutting and swimming evolve Palaeocastorine species divergence Common rodent ancestor exists. Split from Anomalurus

Eucastor Palaeocastor Agnotocastor

Earliest beaver-like fossils recorded in California, Germany, and China

Castor spp. Palaeomys

Steneofiber eseri (not adapted to aquatic lifestyle)

Steneofiber fossor (underground lifestyle)

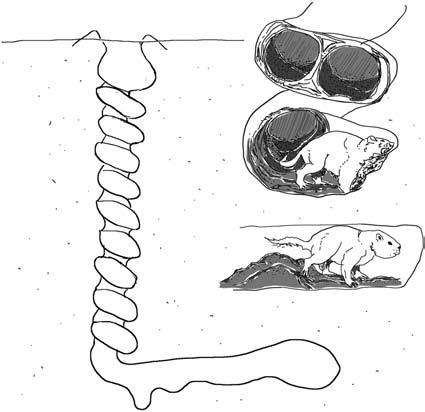

wetlands. Canonical analyses of a wide range of extinct beavers have demonstrated that skull morphology was highly adapted for digging behaviours, though these fossorial features demised around 20 myr (Samuels and Valkenburgh, 2009). Some of these burrowing beavers (three species are associated: Palaeocastor fossor, P. magnus, and P. barbouri) dug unusual, deep, helical burrows, ending in an inclined living chamber (Martin and Bennett, 1977). When first discovered, these structures were described as silicified sponges or extinct plants and named ‘Daimonelix’ (Barbour, 1892; Barbour, 1895). Later, Cope (1893) and Fuchs (1983) proposed these were rodent burrows, with plant material being roots of various plants gnawed during burrow construction, which was later validated (Peterson, 1906; Schultz, 1942). Several thousand of these unusual structures (‘devil’s corkscrews’; Figure 1.5), which can descend to a depth of nearly 3 m and were often found in clusters or ‘towns’, have now been identified in North America (Martin, 1994).Various theories have been proposed as to why these ancient beavers dug such energetically expensive and complex burrows requiring so much effort to construct (Meyer, 1999). This unusual shape was proposed as an efficient space utilization design (Martin and Bennett, 1977), though this was later ruled out as neighbouring burrows are clustered together apparently randomly (Meyer, 1999). Neither did they seem to offer increased predator protection, as the remains of both predated beavers and various predators have been found in these burrows (Martin and Bennett, 1977; Martin, 1994). In the end they concluded that excavated deep, helical burrow systems in arid grasslands maintained a more consistent subsurface temperature and humidity and may even have trapped some water. All burrowing beaver species (up to eight coexisting species known) disappear from the fossil record around the same time, ~20 myr, with those utilizing a more semi-aquatic lifestyle becoming more successful (Hugueney and Escuillie, 1996).

The Eucastor gave rise to Dipoides, another former member of the family Castoridae, sharing the trait of tree exploitation and possessing the woodcutting abilities of the genus Castor, and therefore our modern beavers (Rybczynski, 2007). Though

Figure 1.5 ‘Devil’s corkscrew’ burrows of ancient fossorial beaver ancestors. (Illustration provided courtesy of Rachael Campbell-Palmer, redrawn after Martin & Bennett, 1977.)

Castor and Dipoides share a common wood-cutting ancestor, thought to have been a burrower, which can be traced back at least 24 myr, they are not close relatives but share a semi-aquatic clade (Rybczynski, 2007). Their respective gnawing marks on fossilized tree remains may be difficult to distinguish without careful examination. Dipoides are considered less advanced, producing smaller and more overlapping cuts due to their smaller and more round incisors, compared to the more evolved chisel-like ones seen in beavers today (Tedford and Harington, 2003). The wood-cutting abilities of Castor are more efficient as their straight edge incisors produce larger cuts, taking fewer bites to fell equivalent sizes of woody material than Dipoides with their strongly curved incisors (Rybczynski, 2008). Fossil remains of intertwined cut sticks have also been found in association with them, implying ‘nest-type’ structures that could be evidence of early lodge and/or dam building activities (Tedford and Harington, 2003). Evidence of dam building behaviours and impacts on geomorphology in extinct Castoridae appears lacking, though wood cutting pre-existed modern beavers (Plint et al., 2020).

Modern beavers (genus Castor) first appeared during the Late Miocene and Pliocene (11–2.5 myr) as one common species around the Palaearctic region (Xu, 1994; Rekovets et al., 2009; Rybczynski et al., 2010) from their close relative species Steneofiber (Xu, 1994; Rybczynski, 2007; Flynn and Jacobs, 2008). Castor praefiber (Depéret, 1897) for example is considered an intermediate species in Castor fiber evolution thought to have first appeared in the early Pliocene (Rekovets et al., 2009). The genus Castor is believed to have emerged in Eurasia and then penetrated into North America via the Bering land bridge (Lavrov, 1983; Lindsay et al., 1984; Xu, 1994; Hugueney and Escuillie, 1996; Flynn and Jacobs, 2008) during the Pliocene around 4.9–6.6 myr (Lindsay et al., 1984; Xu, 1994). The earliest C. fiber is known from is the Early Pleistocene (Barisone et al., 2006; Rekovets et al., 2009), and it is thought to have overlapped with Castor plicidens (Cuenca-Bescós et al., 2015).

Trogontherium was a congener of modern beavers; these were the giant beavers of Eurasia, though widely distributed throughout the Palaearctic, comprising three species, T. minutum , T. minus , and the largest T. cuvieri, in the Upper Pliocene (Mayhew, 1978; Fostowicz-Frelik, 2008). Their fossil remains have been discovered regularly with those

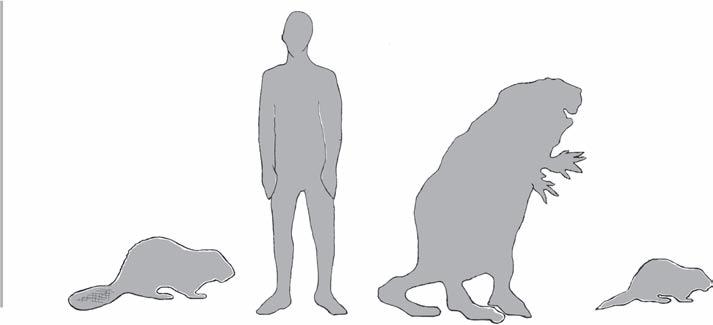

of the genus Castor in both Europe and Asia from the Early Pleistocene (~2.4–0.13 myr), and the recent finding of a specimen in China has extended its extinction date to the Late Pleistocene (Yang et al., 2019). It appears that modern beavers lived alongside or were possibly locally extirpated by the slightly larger Trogontherium cuvieri, as the prevalence of the two forms at archaeological sites demonstrates an inverse relationship (Mayhew, 1978). Additionally, this places the survival of this giant beaver as overlapping with Pleistocene people and therefore a candidate with the other extinctions of large Ice Age mammals caused by human activities (Yang et al., 2019). Figure 1.6a and b shows comparison sizes.

More recent genetic studies have determined that divergence between our two modern species occurred around 7.5 myr (Horn et al., 2011). The Bering land bridge would have permitted animal movements between Eurasia and North America. After the land bridge disappeared this most likely triggered the speciation into C. fiber and C. canadensis as they became completely isolated from each other (Horn et al., 2011). The Eurasian beaver is therefore thought to be around twice as old, dating back around 2 myr. Genetic differences and lack of hybridization are evident, but their biology,

Figure 1.6a Modern beaver size in relation to Homo sapiens, their giant ancestor Castoroides, and Dipoides. (Illustration provided courtesy of Rachael Campbell-Palmer, redrawn after Scott Woods, Western University, Canada.)

morphology, and physiology remain remarkably similar, along with their shared ancient, coevolved parasites, the beaver beetle Platypsyllus castoris and stomach nematode Travassosius rufus (Lavrov, 1983; see Chapter 8).

Today’s beavers are the second largest species of rodent in the world (the largest being the capybara, Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris, from South America), although the now-extinct giant beavers (genus Castoroides) really capture the imagination. It is believed that giant beavers and modern beavers shared most of the same range, with fossils found from Alaska to Florida (Kurtén and Anderson, 1980). These giant beavers existed in North America during the Pleistocene and were one of the last megafauna (typically defined as animals with body weights > 44 kg; Martin, 1984) to go extinct near the end of this epoch—thought to be due to a combination of climatic and anthropogenic impacts (Boulanger and Lyman, 2014; Cooper et al., 2015). One such giant beaver Castoroides leiseyorum, was thought to reach adult body sizes of 2.5 m in length and weigh between 150 and 200 kg (Kurtén and Anderson, 1980) and was known to exist throughout the southeastern USA (Parmalee and Graham, 2002). Another, Castoroides ohioensis, thought to have been one of the last of the giant beavers, disappeared around 10,000 years ago (Boulanger and Lyman, 2014). There are conflicting theories on giant beaver ecology, especially regarding their tree cutting and dam and lodge building abilities, as little evidence of these structures exist (Rybczynski,

2008), though their large body size and short limbs are thought to have made them poorly adapted for terrestrial life (Plint et al., 2019).

However, very recent palaeodietary studies have used stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis of bone collagen to confirm these beavers were likely to be cold-tolerant and highly dependent on submerged and floating macrophytes, a significant factor allowing C. canadensis to coexist, as they would have exhibited complementary dietary niches (Plint et al., 2019). This dietary analysis did not support tree material consumption, which is consistent with their dental morphology (Rinaldi et al., 2009), both indicating giant beavers had to rely on significant existing wetlands (Plint et al., 2019). Fossil finds display rounded incisors with blunt tips, and this has prompted researchers to believe these teeth were used to cut off and grind coarse swamp vegetation rather than trees (Kurtén and Anderson, 1980).

Evidence for the last known giant beaver populations is concentrated in the Great Lake Basins, northern USA, and Ontario, Canada, where they are thought to have hung on before their final extinction (Boulanger and Lyman, 2014). Although there is evidence of giant beavers and humans overlapping in these areas for ~1,000 years, no evidence of them hunting these animals currently exists (Boulanger and Lyman, 2014). It is therefore concluded that changes to warmer and drier climatic conditions resulted in suitable wetland habitat loss through reduction in glacial melt water and sediment infilling, with associated changes in woody vegetation and giant beavers being reduced to small, isolated populations that eventually died out completely (Plint et al., 2019); on the other hand, Castor spp. possessed incisors, allowing tree felling, taking advantage of woody tree species, and would have had the ability to create new habitats, giving them a competitive edge (Plint et al., 2019).

1.6 Modern beavers

Extant beavers were first named and described as Castor fiber by Linnaeus (1758), while Kuhl first named and described Castor canadensis (1820). Fossil

Figure 1.6b Giant beaver replica skull in comparison to beavers today.

(Photo supplied courtesy of Michael Runtz.)

(b)

evidence of Eurasian beavers has been found in Italy, Spain, Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Israel, and Iran, but the species is thought to have gone extinct in southern Eurasia by the Late Holocene (Linstow, 1908; Legge and Rowley-Conwy, 1986; Barisone et al., 2006). For example, fossil evidence of Eurasian beaver from Spain documents their presence from the Early Pleistocene ~1.4 myr, but then there is a great absence of remains during the Middle Pleistocene when human occupation intensified and suitable habitat most likely became scarcer (Cuenca-Bescós et al., 2015). Both beaver species remained widespread in suitable freshwater habitats throughout the northern hemisphere successfully until human populations grew and began to exploit them, beginning in Eurasia (see Chapter 2). The mass exploitation of beavers, to the point of near complete extinction, has impacted on both their modern distribution and subspecies classification. For both species the usage of subspecies names is complicated by inconsistent application in the literature, with some names not following the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and based on contested scientific data such as differences only in relict population survival location (Gabrys and Wazna, 2003). Table 1.5 shows the historical classification of subspecies for both extant beaver species.

The greatest impact on Eurasian beavers, with the most rapid period of decline, occurred in the nineteenth century, by the end of which this species was on the verge of becoming extinct and reduced to a handful of populations in fragmented refugia left after the fur trade, thought to number 1,200 individuals overall (Veron, 1992; Nolet and Rosell, 1998). As a side note, in some early taxonomical descriptions the Eurasian beaver was classified as two species—the eastern beaver, C. fiber, and the western beaver, C. albicus—by Matschie (1907) based on craniological differences (Lavrov, 1981; Lavrov, 1983). Most zoologists at that time, however, recognized only two contemporary species, the North American and a single Eurasian species (Figure 1.7a Eurasian and Figure 1.7b North American), so this third species (C. albicus) was rejected and placed in subspecies classification, which themselves underwent several debates (Gabryś and Ważna, 2003). Ancient beaver DNA

analysis does not provide any evidence to support defined substructure categories, instead forming part of a continuous clade (Horn et al., 2014; Marr et al., 2018), though divergence in mtDNA haplotypes is evident (eastern and western phylogroups), caused by population retreat into glacial refugia during the last Ice Age (~25,000 years ago) (Durka et al., 2005). So enough defined, it was recommended they be managed as separate evolutionary significant units (ESU) (Durka et al., 2005). ESUs are largely defined as reciprocally monophyletic mtDNA units exhibiting significant divergence of allele frequencies at nuclear markers and in regard to conservation management can suggest sourcing for reintroductions (Moritz, 1994; Frosch et al., 2014). Ancient beaver populations were pretty much continuous across the whole of Eurasia and although the two main lineages were apparent, so too was a higher degree of haplotype diversity, and later differences determined in the remaining relict populations were not as stark (Horn et al., 2014). Comparison of DNA from fossil beavers with modern beavers (using samples ranging from several hundred to 11,000 years old) demonstrates Eurasian beavers have suffered a significant genetic bottleneck, losing at least a quarter of their unique haplotypes (Horn et al., 2014). This loss of genetic diversity occurred during the Holocene, when human populations expanded (Horn et al., 2014), with the most recent impact and distribution strongly linked with human activities (Halley et al., 2020).

These nine relict populations, characterized by low genetic variability and a low proportion of polymorphic loci (Ellegren et al., 1993; Babik et al., 2005; Ducroz et al., 2005), were previously considered to be distinct subspecies based on morphological skull measurements, disjunct distribution (Lavrov, 1981; Heidecke, 1986; Frahnert, 2000), and mitochondrial differences, including proportion of assignment to eastern or western clades (Durka et al., 2005). The Belarus refuge has more recently been determined to be the most genetically diverse compared to all the other relict populations, given its larger population size and more complex distribution remaining at isolated locations across several water basins while it passed through this genetic bottlenecking (Munclinger et al., in prep).

Table 1.5 Historical subspecies classification for both extant beaver species. Note many of these are no longer formally recognized as a subspecies or referred to as a fur trade refugia (Gabryś and Ważna, 2003; Pelz-Serrano, 2011).

Species

C. fiber

C. canadensis

Subspecies Region

C. f. albicus

C. f.galliae

C. f. fiber

C. f. belarusicus

C. f.orientoeuropaeus

C. f.pohlei

C. f. tuvinicus

C. f. birulai

C. f. vistulanus

C. c acadicus

C. c.baileyi

C. c.belugae

C. c. caecator

C. c. canadensis

C. c. carolinensis

C. c. concisor

C. c. duchesnei

C. c. frondator

C. c. idoneus

C. c. labradorensis

C. c. leucodontus

C. c. mexicanus

C. c.michiganensis

C. c. missouriensis

C. c.pacificus

C. c.pallidus

C. c.phaeus

C. c.repentinus

C. c. rostralis

C. c.sagittatus

C. c. shastensis

C. c. subauratus

C. c.taylori

C. c. texensis

Germany (Elbe), Poland

France (Rhone)

Norway

Belarus, northern Ukraine

Russia (Voronez), Belarus

Western Siberia, Urals

South-central Siberia

Southwest Mongolia, China

Vistula, Poland

New Brunswick, New England, Nova Scotia, Quebec

Humboldt River, Nevada

Yukon, Alaska

Newfoundland

Canada, British Columbia

North Carolina, Louisiana, Mississippi

Colorado, Mexico

Duchesne River, Utah

Rio San Pedro, Mexico border

Oregon, Washington

Labrador rivers

Vancouver Island, British Columbia

New Mexico, Texas

Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota

Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Missouri, Dakota

Washington, British Columbia, Idaho

Raft River, Utah

Pleasant Bay, Alaska

Grand Canyon, Arizona

Red Butte Canyon, Utah

British Columbia, Yukon, Idaho

Shasta Mountains, California

California

Big Wood River, Idaho

Cummings Creek, Texas

References

Matschis (1907)

Geoffroy (1803)

Linneaus (1758)

Heidecke (1986)

Lavrov (1981)

Serebrennikov (1929)

Lavrov (1969)

Serebrennikov (1929)

Matschis (1907)

Bailey and Doutt (1942)

Nelson (1927)

Taylor (1916)

Kuhl (1820); Banngs (1913)

Rhoads (1898)

Warren and Hall (1939)

Durrant and Crane (1948) Mearns (1898)

Jewett and Hall (1940)

Bailey and Doutt (1942)

Gray (1869)

Bailey (1913)

Bailey (1913)

Bailey (1919)

Benson (1933)

Durrant and Crane (1948)

Heller (1909)

Goldman (1932)

Durrant and Crane (1948)

Benson (1933)

Taylor (1916)

Taylor (1912)

Davis (1939)

Bailey (1905)

Since the 1900s, beaver numbers have recovered throughout much of their former European range as a result of a combination of legal protection (species and habitat), reduction in hunting pressure and increased regulation, land-use shifts including farmland abandonment, proactive reintroductions/ translocations, and natural recolonizations (Deinet et al., 2013; see Section 2.8.1). Genetic analysis of mitochondrial DNA and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) DRB gene sequences demonstrates low diversity within these refugia populations, though distinctions between them do exist (Babik

et al., 2005; Ducroz et al., 2005; Durka et al., 2005). Despite large geographical distances, there was no significant genetic differentiation between Mongolian and eastern Russian beaver populations (Ducroz et al., 2005). No major variations in haplotypes have been found within central European relict populations (Durka et al., 2005). However, some skull morphometric analyses suggest some evidence for relict population differentiation (Frahnert, 2000) and behavioural discrimination studies indicate lesser recognition and reactions to anal gland secretions between, C. f. fiber (relict Norwegian) and C. f. albicus (relict German), different Eurasian subspecies (Rosell and Steifetten, 2004). Whilst distinctive eastern (Russia, Belarus, Siberia, and Mongolia) and western (relict France, Germany, and Norway) clades based on genetic differences based on mtDNA have been found (Durka et al., 2005; Horn et al., 2014), as for many European mammals following the last Ice Age, hybridization zones are also apparent. Recent genetic studies dismiss these differences as being significant enough to warrant subspecies classification, as the remnants of a once much more diverse, mixed, and expansive population, now relegated to the artefact of human hunting and recent anthropogenic genetic bottlenecking rather than previously separated subspecies (Horn et al., 2014). This has been supported by nuclear and mitochondrial analyses (Frosch et al., 2014; Horn et al., 2014; Senn et al., 2014). Recent genetic analysis has concluded that much of Europe and Russia is now populated by admixed beavers, resulting in increased genetic diversity leading to viable and successfully expanding populations,

indicating that outbreeding depression is not a significant impact (Munclinger et al., in prep). Some authors still argue for the recognition of certain subspecies/populations, for example Siberian beavers, C. f. pohlei, defined as possessing a specific haplotype marker (Saveljev and Lavrov, 2016), and C. f. tuvinicus and C. f. birulini populations in Mongolia and China given their long period of isolation (Munclinger et al., in prep).

Genetic screening of modern-day Eurasian beaver populations demonstrates that the degree of mixing between eastern and western lineages is already so advanced (Frosch et al., 2014; Senn et al., 2014) across several areas in Eurasia that it seems pointless to try and maintain this former glaciation and geographically induced clade separation, especially as anthropogenic translocations continue and naturally population expansion leads to secondary contact and mixing across their native range (Frosch et al., 2014). Recent genetic analysis of the current population determined that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and nuclear microsatellites reflected the composition of the founder animals and that admixture zones occurred (Minnig et al., 2016). Recent recovery through both natural spread and reintroductions demonstrates that beavers from these relict populations are meeting and admixing (Frosch et al., 2014). Poland for example is a modern-day mixing zone, where as a result of natural range expansion and multiple translocations, admixed populations now exist, with both lineages represented (Biedrzycka et al., 2014).

One of the most detailed genetic analyses of the Eurasian beaver genome was undertaken by Senn

Figure 1.7a Adult Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber). (Photo supplied courtesy of Frank Rosell.)

(a)

(b)

Figure 1.7b Adult North American beaver (Castor canadensis). (Photo supplied courtesy of Jan Herr.)