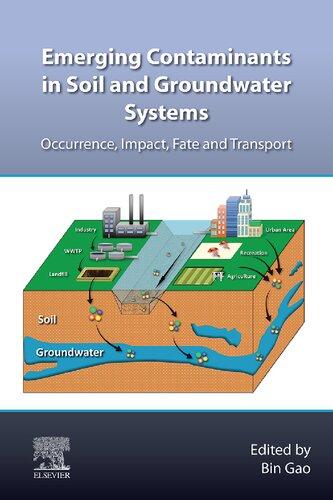

ArmiesandPolitical ChangeinBritain, 1660

–1750

HANNAHSMITH

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©HannahSmith2021

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted FirstEditionpublishedin2021

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2021939484

ISBN978–0–19–885199–8

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198851998.001.0001

PrintedandboundintheUKby TJBooksLimited

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Acknowledgements

IamgratefulfortheassistanceandencouragementthatIhavereceivedwhile researchingandwritingthisbook.Iacknowledgewiththanksthe financial supportthatIhavereceivedfromTheLeverhulmeTrustthroughtheawardofa PhilipLeverhulmePrize;theHenryHuntingtonLibrary,SanMarinothroughthe awardofanAndrewW.MellonFoundationFellowship;theBritishAcademyfora SmallResearchGrant;theJohnFellOUPResearchFund,UniversityofOxfordfor theawardofagranttoassistwithteachingreplacementcostswhileIheldthe PhilipLeverhulmePrize;theUniversityofHullforappointingmetoanRCUK AcademicFellowshipandLectureshipinHistory;andStHilda’sCollege,Oxford forassistancewithresearchcosts.

IwouldliketothankEricaCharters,OliverCox,JulieFarguson,Gabriel Glickman,MarkGoldie,AaronGraham,HolgerHoock,DominicIngram,Clyve Jones,MaxKaufman,NiallMacKenzie,MatthewMcCormack,EveRosenhaft, MichaelSchaich,WilliamTatum,andStephenTaylorfortheirhelpatvarious stagesoftheproject.IwouldsimilarlyliketothankPeterGriederandDavid OmissiattheUniversityofHull,colleaguesattheHistoryFaculty,Universityof Oxford,andcolleaguesatStHilda’sCollege,Oxford,especiallyKatherineClarke, JanetHowarth,RuthPercy,CatherineSchenk,andSelinaTodd.

Earlychaptersofthisbookwerepresentedatseminarsandconferencesatthe UniversityofOxford;GermanHistoricalInstitute,London;NationalArmy Museum,London;UniversityofLeicester;UniversityofNorthampton;Birkbeck College,UniversityofLondon;UniversityofLeeds;andEcoleNormale Supérieure-LettresetSciencesHumainesdeLyonUniversitéLumièreLyon2. Iwouldliketothanktheparticipantsfortheirconstructivecommentsand questionswhichhelpedmetodevelopmyarguments.Iamparticularlygrateful totheanonymousreadersforOUPwhoprovidedinsightfulfeedbackatcritical points.MythanksarealsoduetomyeditorsatOUP,KatieBishop,Stephanie Ireland,CathrynSteele,andChristinaWipfPerry.

Iammuchindebtedtothestaffofthelibrariesandarchivescitedinthe Bibliography.IwouldparticularlyliketothankGayeMorganattheCodrington Library,AllSoulsCollege,Oxford;MarkBainbridgeatWorcesterCollegeLibrary, Oxford;AnnaRiggsatBathAbbey;MarkForrestatWimborneStGiles;Anna McEvoy,HouseCustodian,StoweHousePreservationTrust;ChrisBennettat HertfordshireArchivesandLocalStudies;thestaffoftheSpecialCollections ReadingRooms,BodleianLibraries,Oxford;andSamanthaSmartatthe NationalRecordsofScotland.

IthankandacknowledgethepermissionoftheSyndicsofCambridge UniversityLibrarytocitefromSPCKMSandWalpole(Houghton)MSS,Ch (H)Pol.Papers;BedfordshireArchivesServicetociteL30/9a/1page117andL30/ 9a/4/181–182;theUniversityofNottinghamManuscriptsandSpecialCollections tocitefromthePortlandandMellishcollections;theProvostandFellowsof WorcesterCollege,OxfordforpermissiontocitefromtheClarkePapers,MS75 andMS81;theEarlDeLaWarrtocitefromthecorrespondenceofJohnWest, LordDeLaWarr;LordWalpoletocitefromthecorrespondenceofHoratio Walpole,BaronWalpole;JimLowtherandtheLowtherEstateTrusttocitefrom theLonsdalepapers;andtheCumbriaArchiveCentre,Carlislefortheirassistance. MaterialfromtheGoodwoodArchivesiscitedbycourtesyoftheTrusteesofthe GoodwoodCollectionsandwithacknowledgementstotheWestSussexRecord Office.MaterialheldattheNationalRecordsofScotland,GD18Clerkof Penicuik,isincludedbypermissionofSirRobertM.ClerkofPenicuik,Bt.,and GD220fromtheMontrosemunimentsisincludedbythepermissionoftheduke ofMontrose.U1590O142/9,3rdearlofShaftesburytoBenjaminFurley,Kent Archives,ispublishedwiththepermissionofthe12thearlofShaftesbury.

Chapter6isbasedonHannahSmith, ‘TheHanoverianSuccessionandthe PoliticisationoftheBritishArmy’,in TheHanoverianSuccession:DynasticPolitics andMonarchicalCulture,editedbyAndreasGestrichandMichaelSchaich (Farnham:Ashgate,2015),207–226andisincludedbypermissionofTaylor andFrancisGroup.

Iwishtorecordmygratitudeandthankstomyfamilywholivedwiththisbook formanyyears.Iwouldliketothankmymother,BrendaSmith,forproofreading chapters.MatthewGreenwoodhasbeenconstantlysupportiveandhasassistedin somanyways.Thisbookisdedicatedtohim.

ListofIllustrations ix

ListofAbbreviations xi Introduction1

1.TheRestorationofCrownandChurch,1660–7012 ITheCreationoftheKing’sArmy16 IIConventiclersandCatholics25 IIITheKing’sGeneral31

2.Popery,ArbitraryGovernment,andWar,1670–838 ITheProblemsofWar39 IITheProblemofParliament45

IIITheProblemofFrance48

3.TheDisputedSuccession,1678–8554 ITheMilitaryDimensionstotheExclusionCrisis55 IITheCrown’sPowerandtheCrown’sArmy63 IIITheRivalHeirs70

4.Revolutions,1685–981

ITheKingandHisArmy86 IIDividedbytheSword94 IIIPoperyonParade?102 IVDownfall107

5.WarandPeace,1689–1702124 IConstructingWilliamIII’sArmy128 IIThePriceofanArmy146 IIICrownandParliament155 IVTheStandingArmyDebates165

6.TheWarofSuccession,1702–14173 ITheWaroftheSpanishSuccessionandtheRageofParty175 IITheAgeofAnne,theAgeofMarlborough182 IIIWhoseArmy?AnneversusMarlborough187 IVTheProblemoftheCaptain-General194 VDesperateMeasures208

7.DefendingandDisputingtheRivalKings,1714–50218

8.OligarchyandOpposition,1714–50251

ListofAbbreviations

BL TheBritishLibrary,London

CJ CommonsJournal

Cobbetted. PH Cobbett, TheParliamentaryHistoryofEnglandfromtheEarliest PeriodtotheYear1803

CSPD CalendarofStatePapersDomestic

CSPV CalendarofStatePapersVenetian

CUL CambridgeUniversityLibrary,Cambridge

EHR EnglishHistoricalReview

GM Gentleman’sMagazine

Grey’sDebatesDebatesoftheHouseofCommons,fromtheYear1667tothe Year1694:CollectedbytheHonbleAnchitellGrey

HHL HenryHuntingtonLibrary,SanMarino

HJ HistoricalJournal

HoC www.historyofparliamentonline.org

HoL TheHouseofLords1660–1715

JBS JournalofBritishStudies

JSAHR JournaloftheSocietyforArmyHistoricalResearch

KHLC KentHistoryandLibraryCentre

LJ LordsJournal

Morrice, EntringBookTheEntringBookofRogerMorrice,1677–1691

NLS NationalLibraryofScotland

NRS NationalRecordsofScotland

OxDNB OxfordDictionaryofNationalBiography

P&P PastandPresent

POAS PoemsonAffairsofState

TNA TheNationalArchives,Kew

WCL WorcesterCollegeLibrary,Oxford

Introduction

Inthefreezingwinterof1659–60anarmymarchedsouthfromScotland.Under thecommandofGeneralGeorgeMonck,itsmenmade ‘theirBedsupontheIce’ andtravelled ‘overMountainsofSnow,toredeemtheirCountrey ’.¹InEngland therepublicanregimethathadexistedforoveradecadesinceCharlesI’ sexecutionwasincrisis.OliverCromwell,themanwhohadheldtheregimetogether, wasdeadandhissonandsuccessor,Richard,hadfailedtounitethedifferent politicalandmilitarygroupingswhowerestrivingforpower.Monck,theregime’ s militarycommanderinScotland,decidedtointerveneandsetoutonthelong journeytoLondon.Monck’sarrivalintheEnglishcapitalwithhissoldiersproved pivotaltotherepublic’sdemiseandledtotherestorationoftheStuartmonarchy inMay1660.Monck’smilitarystrength,basedonhiscarefulmanagementofhis army ’sinterests,enabledhimtobringaboutapro-monarchistparliament,who invitedtheexiledCharlesIItoreturntoEnglandasking.

Nearlyninetyyearslater,troopsfromasuccessortoMonck’sarmymoved norththroughEnglandintheautumnandwinterof1745–6inequallybitter weathertopreservearegime.TheywerebentoncrushingtheJacobiterebelswho wishedtodethronetheincumbentmonarch,GeorgeII,andrestoretheonceagain exiledStuartdynasty.UnderthecommandofGeorgeII’sson,WilliamAugustus, dukeofCumberland,troopsdefeatedtherebelsatthebattleofCulloden,near Inverness,andsecuredthepoliticalsettlementestablishedbytheRevolutionof 1688–9.

Intheyearsbetween1660and1750armiesexertedaprofoundinfluenceonthe courseandoutcomeofpoliticaleventsintheBritishIsles.Monck’sforceshelped tosetCharlesIIonthethrone.JamesVIIandII’sarmyroutedtherebelswho aimedtodethronehimin1685,butthedefectionandparalysisofhisarmyinthe faceofWilliamofOrange’sforceswascrucialtothesuccessoftheRevolutionof 1688–9,whichknockedhimoffhisthronesandreplacedhimwithWilliamof OrangeandJames’sdaughter,Mary.Twenty-fiveyearslater,elementswithin QueenAnne’sarmycontemplatedmilitaryinterventionattheendofherreign toensuretheProtestantSuccessionoftheHanoveriandynastyin1714.GeorgeI’ s andGeorgeII’sarmiesdefendedthemduringthe ’15and ’45Rebellions.

¹ThomasGumble, TheLifeofGeneralMonck,DukeofAlbemarle,&c.withRemarksuponHis Actions (London,1671),p.190.

ArmiesandPoliticalChangeinBritain,1660–1750.HannahSmith,OxfordUniversityPress.©HannahSmith2021. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198851998.003.0001

Thethreatorhopeofthearmy’sinterventionanimatedtheperiod.1660–1saw thefoundationofthe firstroyalarmyinpeacetime,itsveryexistencecontroversial anddisputed.Armieswerepoliticallyengaged,sometimesatapersonallevel,oras Crownservantsenforcingdivisive,repressivepolicies.Wouldamonarchemploy troopstoestablisharbitrarygovernmentandpopery?Couldanarmydetermine thesuccessiontothethrone?Mightanambitiousgeneralusearmedforceto achievesupremepower?Thesequestionstroubledsuccessivegenerationsofmen andwomen.ThehistoryofBritainbetween1660and1750wasshapedbythe actions,apathies,andfearsofarmies.

IThereonceexistedaviewthattheBritisharmywasapolitical,orapoliticalin comparisontoothernationalarmies.Suchaperceptionwasbuttressedbythe stridentclaimsofearlytwentieth-centuryBritisharmyofficerswhocombinedthe notionthatthearmyasaninstitutionexistedbeyondthe ‘mireofpartypolitics’ withadeepdistasteforpoliticians.²HewStrachan’ s ThePoliticsoftheBritish Army,whichfocusedonthenineteenthandtwentiethcenturies,challengedthis opinion.AsStrachanremarked,theargumentthatthearmywasapoliticalwas itselfapoliticalstatement,andheconcludedthat ‘thebehaviouroftheBritish armyisasinherentlypoliticalasthatofotherarmies ’.³

EarlierhistorianshadacknowledgedthattheBritisharmy’sopeningyearswere markedbypoliticalinvolvement.Afterall,theinterventionofgroupswithinthe armyintheRevolutionof1688–9couldscarcelybepassedover.Butsuch intrusionswereviewedthroughthesameprismofapoliticism;unsurprising, giventheprevailingmaximthatmilitaryhistoryshouldbewritten,couldonly bewritten,bythemilitary.SirJohnFortescueopenedhismonumentalhistoryof theBritisharmy, firstpublishedin1899,withanapologythat ‘thecivilianwho attemptstowriteamilitaryhistoryisofnecessityguiltyofanactofpresumption’ . ⁴ A fifthson,Fortescuehadwantedtojointhearmylikehisolderbrothers. However,holdingacommissioninthelatenineteenth-centuryBritisharmywas acostlybusiness,principallyowingtotheextraordinaryoutlayonuniformsand horsesandtheequallyextraordinarysociallife theyoungWinstonChurchill hadtospongeoffrelativestopayforhismilitarycareer.Fortescue ’sfathercould notaffordit.PerhapsFortescuewrotelikethearchetypalpepperyoldcolonelby wayofrecompense.⁵ Fortescue ’spredecessorsinthe field,GeneralViscount

²HewStrachan, ThePoliticsoftheBritishArmy (Oxford,1997),pp.6–7. ³Strachan, Politics,pp.7,263.SeealsoDavidCannadine, TheDeclineandFalloftheBritish Aristocracy (NewHaven,CT,1990),p.271.

⁵ OxfordDNB, ‘JohnFortescue’;Cannadine, DeclineandFall,p.270. 2

⁴ J.W.Fortescue, AHistoryoftheBritishArmy,vol.1(1899;London,1910),p.v.

WolseleyandCol.CliffordWalton,werearmyofficers(althoughWalton,atleast, wasmuchless fiery).⁶

Fortescuewasinterestedinsketching ‘thepoliticalrelationsbetweentheArmy andthecountry’.Butinpractice,hisendeavourstowritethe ‘politicalnotless thanthemilitaryaspectoftheArmy’shistory...atthesacri ficesometimesof purelymilitarymatters’ meantthatapartfromtheeventsof1688,heconfined himselftochartingandcastigatingparliamentaryresponsestothearmywhennot describingmilitarycampaigns.⁷ Hewasespeciallyvehementwhendealingwith themilitarydisbandmentofthelate1690s,whichhedenouncedas ‘anactof criminalimbecility,themostmischievousworkofthemostmischievous ParliamentthathaseversatatWestminster’ . ⁸ Heexpressedfuryattheconduct of ‘[Robert]Harleyandhisgang’ inseekingtheremovalofQueenAnne’scaptaingeneral,thedukeofMarlborough,frommilitarycommandandholdingfurtive peacenegotiationswithLouisXIV,which ‘mustnotbeforgotteninthehistoryof therelationsoftheHouseofCommonstowardstheArmy’ . ⁹ Andherather extraordinarilyobserved,whencommentingonthemutinyamongBritishtroops inFlanderstowardstheendoftheWaroftheSpanishSuccession, ‘Fortunateit wasthattheoutbreaktookplacewhilethetroopswerestillabroad,ortheHouseof Commonsmighthavelearnedbyasecondbitterexperience[aglanceatmilitary interventionduringtheCivilWarsandInterregnum]thatthepatienceofthe Britishsoldier,thoughverygreatisnotinexhaustible’.¹⁰ Inessence,politicswas metedoutbymeddling ‘civilian’ politicianstolong-sufferingsoldiers.¹¹ Admittedly,Fortescueencounteredmajorpracticalresearchdifficultiesin attemptingtoshiftthespotlightbeyondoperationalhistory,amongwhichshould beincludedhispecuniarytroubles.Hisprojectwaspartlysponsoredbyhis redoubtablewifeWinifred ’sfashionretailbusiness.¹²

Subsequentshiftsinthe fieldsofhistoryandthesocialscienceshaveprovided scholarswithnewframeworkswithwhichtoanalysethepoliticsofthelate seventeenth-andeighteenth-centuryarmies.Militaryhistory’sre-orientation awayfromregimentalhistoriesandnarrativesofcampaignstoconsiderthe

⁶ ViscountWolseley, TheLifeofJohnChurchillDukeofMarlborough (London,1894);Clifford Walton, HistoryoftheBritishStandingArmyA.D.1660to1700 (London,1894).Asmightbeexpected, boththesestudiesfocusoncampaignsandaspectsofthearmy’sinstitutionalhistory,although WolseleyanalysedwhetherJohnChurchill’sbehaviourin1688wasjustifiableanddeclaredthat ‘the GovernmentortheGeneralwhocountsupontheBritishsoldierto fightwellinanunrighteousand unjustcause,reliesforsupportuponareedthatwillpiercethehandwhichleansuponit’:Wolseley, Life,vol.2,p.85.Waltonnotedthearmy’srolein1688.

⁷ Fortescue, History,vol.1,pp.vii,304–309;Strachan, Politics,p.6.

⁸ Fortescue, History,vol.1,p.389. ⁹ Fortescue, History,vol.1,p.541.

¹

⁰ Fortescue, History,vol.1,pp.553–554.

¹¹Fortescuedevelopedthethemeinthepost-1713periodtoo.SeeFortescue, History,vol.2, pp.24–27.

¹²Fortescue, History,vol.1,p.vii; OxfordDNB, ‘WinifredFortescue’.Lieut.-Col.J.S.Omondprovided abriefoverviewoftherelationsbetweentheCrown,parliament,andthearmyin Parliamentandthe Army,1642–1904 (Cambridge,1933)tomitigatethedearthofliteratureonthetopic.

4

relationshipbetweenwarandsocietieshasenabledarmiestobeplacedwithinthe contextof ‘theworldtheybelongto’,asGeoffreyBestexpressedit.¹³Meanwhile, inthe1950sand1960s,politicalscientistsbecameinterestedintheorizingmilitary intervention,albeitinhistoricallyinsensitiveways.Withoutdoubtsomeoftheir preoccupations,forinstancethedebateoverwhetherprofessionalarmieswere moreorlesslikelytobeinvolvedinpolitics,hadmuchlessrelevanceforthepremodernera,notleastbecausetheirprimeconcernswererelatedtotheUnited Statesmilitaryintheshadowoftheatomicbomb.¹⁴

Bythe1970sand1980sthehistoryofthelateseventeenth-andearly eighteenth-centuryBritisharmies,andwithitthepoliticalactivitiesoftheir members,wasatlastcomingunderseriousacademicscrutiny.JohnChilds undertookadetailedconsiderationofthepoliticalfunctionandoutlookofthe armiesofCharlesII,JamesVIIandII,andMaryIIandWilliamIIIwithinhis seminaltrilogyontheirmilitarycomposition,size,andfunction.¹⁵ Childs’svaluableworkhighlightedtheimpactofwiderpoliticaldevelopmentsonstaffing armies:theroyalistinfluxintoCharlesII’snewarmyintheearly1660s;the purgingofWhigarmyofficersduringtheExclusionCrisisandthosewhochallengedJamesVIIandII’spro-Catholicpoliciesinthemid-1680s;andWilliam III’srestructuringoftheBritisharmyaftertheRevolutionof1688–9toremove Jacobitesympathizers.ChildsalsoanalysedhowtheStuartkingsdeployedtheir armiesatkeypoliticalmoments,notablyatthetimeoftheOxfordParliamentin 1681andbetween1685and1688.¹⁶ Childs’sstudieswerecomplementedbyJohn Miller’sworkonCatholicofficersinCharlesII’sandJamesVIIandII’sarmiesand themilitiainJames’sreign.¹ ⁷ ThepoliticalhistoryofQueenAnne’sarmytooka differenttrajectory.R.E.Scoullerpublisheditsdetailedinstitutionalhistoryinthe 1960sbutdidnotengagewiththepoliticsofthearmy.¹⁸ Itwaslefttohistoriansof thedukeofMarlboroughandhispoliticalworldtoanalysehowtheageofparty hadanimpactonthearmyoftheWaroftheSpanishSuccession(1702–13).¹⁹ The armiesofthe firsttwoGeorgeshavelikewisebeensubjecttodetailedscrutiny,

¹³SeeBest’ s ‘Editor’sPreface’,inM.S.Anderson, WarandSocietyinEuropeoftheOldRegime, 1618–1789 (Leicester,1988),p.9.

¹

⁴ Strachan, Politics,pp.10–15;IanF.W.Beckett, AGuidetoBritishMilitaryHistory:TheSubject andtheSources (Barnsley,2016),pp.51–52;MorrisJanowitz, TheProfessionalSoldier:ASocialand PoliticalPortrait (NewYork,1960),preface;S.E.Finer, TheManonHorseback:TheRoleoftheMilitary inPolitics (1962,2ndedn1981,London,1988).

¹

⁵ JohnChilds, TheArmyofCharlesII (London,1976); TheArmy,JamesIIandtheGlorious Revolution (NewYork,1980); TheBritishArmyofWilliamIII,1689–1702 (Manchester,1987).

¹

⁶ JohnChilds, ‘TheArmyandtheOxfordParliamentof1681’ , EnglishHistoricalReview 94,no.372 (1979):pp.580–587.

¹

⁷ JohnMiller, ‘CatholicOfficersintheLaterStuartArmy’ , EHR 88,no.346(1973):pp.35–53;John Miller, ‘TheMilitiaandtheArmyintheReignofJamesII’ , HJ 16,no.4(1973):pp.659–679.

¹

¹

⁸ R.E.Scouller, TheArmiesofQueenAnne (Oxford,1966).

⁹ HenryL.Snyder, ‘TheDukeofMarlborough’sRequestofHisCaptain-GeneralcyforLife:AReexamination’ , JSAHR 45,no.182(1967):pp.67–83;IvorF.Burton, TheCaptain-General:TheCareerof JohnChurchill,DukeofMarlboroughfrom1702to1711 (London,1968).

althoughthefocusofsuchstudieshasbeenontheirfunctionandoperationand theirevolutionas fightingforcesratherthantheirpoliticsassuch.²⁰ Inadditionto thesestudies,thearmylistspublishedbyCharlesDaltonbetween1892and1904 andthe HistoryofParliament andthe Office-HoldersinModernBritain volumes broughtintofocusthepoliticalpreoccupationsofarmyofficerswhowereMPsor peersorheldofficeattheroyalcourt.²¹Thishasemphasizedthatanumberof armyofficersweredeeplyentrenchedinpartisan,courtly,andparliamentary politicsorhadnotablyclosetiestotheCrowninanerawhenthemonarchwas stillapowerfulpoliticianaswellasthearmy’ssupremecommander.

AlthoughthemonarchgovernedfromLondon,heorshewasthesovereignof IrelandandScotlandaswellasEnglandandWales.Howtheyruledinone kingdomhadanindelibleimpactontheothers.²²Thishasdistinctimplications whenwritingthepoliticalhistoryofarmiesinBritain.WhileEnglandprovidesthe mainfocusandperspectiveforthisstudy,thisbookalsoconsidersthewider BritishIslescontexts,andAnglo-Scottishrelationsinparticular.Contemporaries wereconcernedbytheCrown’sabilitytousethemilitarypoweritenjoyedinone kingdomoveritssubjectselsewhere.TheScottishparliamentpassedseveralactsin the1660swhichpermittedtheScottishmilitiatobedeployedoutsideofScotland, thuscausingconsiderableEnglishparliamentaryunease.TheScots,too,had groundsforalarmatthemilitaryresourcesoftheEnglishCrown.CharlesII defeatedtheConventiclerrebellionof1679atBothwellBrig,Lanarkshireby dispatchingEnglishtroopstoScotland.In1706–7QueenAnnestationed EnglisharmyregimentsontheAnglo-ScottishbordertodeterScottishopposition totheActofUnionof1707betweenEnglandandScotland.Regimentsraisedin Englandweresentto fightagainstScottishJacobiteforcesin1715and1745–6.

ABritishcontextexistedwithinthearmytoo.Armiesweremicrocosmsof nationaltensionsthatcouldbefoundmorewidelywithintheBritishIsles,with rivalriesexistingbetweentroopsfromdifferentcountries.TherewasnoBritish armyuntil1707;eachkingdomhaditsownarmy.After1707,theEnglishand ScottisharmiesbecameaBritisharmyandIrelandhadaseparatearmyuntilthe UnionbetweenBritainandIrelandin1801.YetEnglish,Irish,Scots,andWelsh mencouldserveinthesenationalarmies,particularlyattherankofcommissioned officer.Indeed,bytheearlyeighteenthcentury,Irishregimentswererecruitedin EnglandtopreventIrishCatholicsenlistingassoldiers.TheIrishProtestantelites welcomedtroopsasdefenceagainsttheCatholicpopulation,thusprovidingthe

²⁰ AlanJ.Guy, OeconomyandDiscipline:OfficershipandAdministrationintheBritishArmy 1714–63 (Manchester,1985);J.A.Houlding, FitforService:TheTrainingoftheBritishArmy, 1715–1795 (Oxford,1981).

²¹CharlesDalton, EnglishArmyListsandCommissionRegisters,1661–1714 (London,1892–1904); andinparticular, Office-HoldersinModernBritain:Volume11(Revised),CourtOfficers,1660–1837,ed. R.O.Bucholz(London,2006), BritishHistoryOnline,www.british-history.ac.uk/office-holders/vol11 [accessed15September2020].

²²Forinstance,seeTimHarris, Restoration:CharlesIIandHisKingdoms (2005;London,2006).

Englishgovernmentwithusefulstoragespaceforregimentsthatitwishedto retainbutcouldnotquarterinEnglandwithoutapoliticaloutcry.²³TheCrown tendedtoviewitsnationalarmiesasoneunit,andtheseparatemilitaryestablishmentsaslittlemorethananaccountingmeasurewhichdeterminedhoweach armywas financed.²⁴

Theevolutionofavibrantandbrashpublicsphereinthisperiodalsohas importantimplicationsforthepoliticalhistoryofthearmies.Popularopinionwas instrumentalinshapingpoliticsandgainedacontroversiallegitimacyofitsown. Monarchswereforcedtoengagewithandpersuadetheirsubjectsusingthepress aswellasthrougholderformsofcommunication.²⁵ Thepoliticalpartiesthat emergedinthelaterStuartperiodhadtowoovotersusingacacophonyof techniques.Partisanpoliticswerearticulatedoutsidetheeliteinstitutionsofthe royalcourtandparliamentthroughastridentprintculture,organizedstreet demonstrationsandprocessions,bell-ringing,bonfires,andfeasting.Alehouses andcoffeehouseswereimportantlocationsfortheexchangeofpoliticalopinions.²⁶ Thearmy,liketheCrown’sothersubjects,waspartofthishighlyvisible, inclusive,engaging,andubiquitouspoliticalculture.Armyofficersweredrawn fromaristocratic,gentry,andgentlemanlybackgrounds.Theyandtheirfamilies andfriendsmightbeenmeshedinnationalandlocalpolitics.Themostwell connectedalsoheldpostsattheroyalcourtorservedinparliament.

Politicalparticipation,however,extendedbeyondthesocialelites,andbeyond thosewhocouldvoteinparliamentaryorcorporationelections.In1696,after thegovernmentdiscoveredaJacobiteplottoassassinateWilliamIII,alladult malesinsomecommunitiessubscribedtoanoathtosupporttheWilliamite regime.²⁷ Thisisanimportantreminderwhenexploringthepoliticsofthose whomcontemporariestermedas ‘thecommonsoldier’.Theelites,forthemost part,viewed ‘commonsoldiers’,likethesocialgroupsfromwhichtheyoriginated, asincapableofprofoundthought,reason,orfeeling;thehistorianwouldbe unwisetodosotoo.²⁸

²³TerenceDenman, ‘“HiberniaOfficinaMilitum”:IrishRecruitmenttotheBritishRegularArmy, 1660–1815’ , TheIrishSword 20(1996–7):pp.148–166.

²⁴ Childs, CharlesII,p.196.

²⁵ KevinSharpe, RebrandingRule:TheRestorationandRevolutionMonarchy,1660–1714 (New Haven,CT,2013);TimHarris, ‘“VeneratingtheHonestyofaTinker”:TheKing’sFriendsandthe BattlefortheAllegianceoftheCommonPeopleinRestorationEngland’,in ThePoliticsoftheExcluded, c.1500–1850,editedbyTimHarris(Basingstoke,2001),pp.195–232.

²⁶ SeeMarkKnights, PoliticsandOpinioninCrisis,1678–81 (Cambridge,1994);TimHarris, LondonCrowdsintheReignofCharlesII:PropagandaandPoliticsfromtheRestorationuntilthe ExclusionCrisis (Cambridge,1987);MarkKnights, RepresentationandMisrepresentationinLater StuartBritain:PartisanshipandPoliticalCulture (2005;Oxford,2006).

²⁷ DavidCressy, ‘BindingtheNation:TheBondsofAssociation,1584and1696’,in TudorRuleand Revolution:EssaysforG.R.EltonfromHisAmericanFriends,editedbyDelloydJ.GuthandJohn W.McKenna(Cambridge,1982),pp.230–233.

²

⁸ YuvalNoahHarari, TheUltimateExperience:BattlefieldRevelationsandtheMakingofModern WarCulture,1450–2000 (Basingstoke,2008),pp.160–161;Houlding, FitforService,pp.267–268.

Informationaboutthosewhoservedintheranksissparseformostofthis period.Thesocialcompositionofnon-commissionedofficersandsoldiersvaried dependingontheregimentandtimeperiod.Thoseservingintheranksofelite regimentsweredrawnfromsemi-genteelbackgrounds.Bycontrast,duringthe yearswhenimpressmentwasinoperation,menwhowereforciblyrecruitedinto thearmyfrequentlycamefromthebottomofthesocialhierarchy.Moregenerally, though,privatesoldierscamefromavarietyoftrades,mostnotablylabourersbut alsoweavers,husbandmen,shoemakers,andtailors,aswellasmanyothers.²⁹ Afewwomenillicitlyenlistedassoldiers.ChristianDaviesandHannahSnellare amongthosewhoachievedsomefamefortheirmilitaryservice.³⁰

The ‘commonsoldier’ cannotbeassumedtobepoliticallyindifferent,too economicallyorsociallymarginalorsubordinatedbymilitaryservicetohold independentpoliticalopinionsoraduesenseofhisrights.³¹Soldierswere quarteredinalehouses,spacesforpoliticaldiscussion,andfreelymixedwithin localcommunities.InLondon,wheretheFootGuardswerequartered,theGuards tookonotherformsofpaidlabour,suchasdockoragriculturalwork.³²Soldiers hadreadyaccesstopoliticaldiscussionand,asservantsoftheCrown,werecalled upontoenforceCrownpolicy.Itisunlikelytheydidsounthinkinglyorwere politicallyuninformed.Overthecourseoftheperiod,itwasincreasinglypossible thatsomesoldierscouldread.MaleliteracyratesinEssexandSuffolkinthe1690s havebeenestimatedataround46percent,whileasampletakenfromnorthern Englandacrossthe1720sto1740ssuggeststhat,amongtheoccupationalgroups fromwhichsoldierswererecruited,37percentoflabourers,33percentof servants,and72percentofcraftsmenwereliterate.In1720sLondon,99per centoftradesmenandcraftsmenmayhavebeenliterate.³³Afewsoldierswere eligibletovoteintheirhomecommunitiesorhadrelativeswhodid,whichgave themsomeformofpersonalpoliticalinfluence.³⁴ Theperiodsawthecontinued expansionoftheelectorate,withthegrowthinthenumberofthosewhoqualified as40-shillingfreeholdersincountyseatsandinthecreationoffreemenandthe divisionofburgagesinboroughs.Ithasbeencalculatedthat4.3percentofthe

²⁹ AndrewCormack, ‘TheseMeritoriousObjectsoftheRoyalBounty’:TheChelseaOut-Pensionersin theEarlyEighteenthCentury (London,2017),pp.334–344;Childs, WilliamIII,pp.116–117.

³

⁰ ForDaviesandSnellseeFraserEaston, ‘Gender’sTwoBodies:WomenWarriors,Female HusbandsandPlebeianLife’ , P&P 180(2003):pp.142–146;JohnA.LynnII, Women,Armies,and WarfareinEarlyModernEurope (Cambridge,2008),pp.66–67.

³¹IlyaBerkovich, MotivationinWar:TheExperienceofCommonSoldiersinOld-RegimeEurope (Cambridge,2017),pp.96,228–229.Forthepoliticsoflateseventeenth-centurysailorsseeJ.D.Davies, GentlemenandTarpaulins:TheOfficersandMenoftheRestorationNavy (Oxford,1991),pp.85–86. ForalaterperiodseeNickMansfield, SoldiersasWorkers:Class,Employment,Conflictandthe Nineteenth-CenturyMilitary (Liverpool,2016),pp.157–158.

³²Cormack, TheseMeritoriousObjects,pp.160,282.

³³DavidCressy, LiteracyandtheSocialOrder:ReadingandWritinginTudorandStuartEngland (Cambridge,1980),pp.99–100;R.A.Houston, ‘TheDevelopmentofLiteracy:NorthernEngland, 1640–1750’ , TheEconomicHistoryReview 35,no.2(1982):pp.206,213.

³⁴ Cormack, TheseMeritoriousObjects,p.293.

populationinEnglandandWalesheldtherighttovoteby1715,thelargest numberofvotersbeforetheparliamentaryReformActof1832.Voterswerenot necessarilywealthyand,insomeboroughs,followedrelativelylow-statustrades andoccupations.³⁵

Soldiers’ politicalopinionswererarelyrecorded.However,prosecutionsfor seditiouswordsandcommentsmadebyobserversprovidesuggestiveindications, especiallyfortheperiodafter1714.Theserecordsilluminateaworldofdeep politicalconvictionandcomplexpoliticalthinkingandactasareminderofthe insightslostforearlierperiods.Contemporariesmayhavebeendismissiveabout thepoliticsofthe ‘commonsoldier’.Nevertheless, ‘commonsoldiers’—astrained andarmed fightingmen wererecognizedashavingformsofpoliticalagency. Theextenttowhichtheregimentasanentityshapedpoliticalidentitiesismore debatable.Alackofsurvivingmaterialmakesitdifficulttoassesswhether regiments,orcompanieswithinthem,hadtheirowndistinctivepoliticaloutlook. Sincearmyofficersandsoldierswerequarteredinrelativelysmallunitsininns andalehousesratherthaninlargergroupsinbarracks,alikelyeffectwasthe weakeningofasenseofregimentalidentity,inpeacetimeatleast.Absenteeismof armyofficersfromtheirdesignatedquarters,aregularproblemduringtheperiod, meantthattheymayhavespentasmuchtimewithnon-armyassociatesand relativesaswiththeirregimentalcolleagues.Thepurchasesystem,wherebyarmy officersboughttheircommission,rendereditharderforacoloneltoshapethe politicalcomplexionofhisregiment.Someregimentsdidhaveareputationfora particularpartisanstandpointoncontroversialissues,forinstanceduringthe ExclusionCrisis,in1688,orinQueenAnne’sreign.Otherregiments,though, appeartohavecontainedavarietyofviews,whichcouldleadtoverbaland physicalaltercationsoverpolitics.Theworldbeyondtheregimentratherthan theregimentitselfseemstohavebeenfarmoreimportantininfluencingthe politicsofindividualofficersandsoldiers.

II

ThisbookanalysestherelationshipbetweenpoliticsandarmiesinBritainfrom thefoundationofapermanentpeacetimearmyin1660–1totheaftermathofthe ’45RebellionandtheendoftheWaroftheAustrianSuccession.Thestudyhas twoobjectives.Itwritesahistoryoftheyearsbetween1660and1750that approacheskeypoliticalepisodesfromadifferentperspectivethanisusually encounteredbycentringthefocusofdiscussiononthearmy.Throughexploring eventsfromthisstandpoint,thebookdemonstrateshowthepoliticalhistoryof

³⁵ W.A.Speck, ToryandWhig:TheStruggleintheConstituencies,1701–1715 (London,1970), pp.13–18,20–21.

theperiodwasshapedbytheloomingpresenceofthearmyand,onoccasion,by theactiveinterventionsofarmyofficersandsoldiers.Moreover,withinthis framework,thebookengageswithaseriesofquestionstoprobetheimpactof thearmyatimportantpoliticalmomentsandasthepolitical,constitutional,and militaryenvironmentchangedafter1689.

Thisisabookaboutthearmyratherthanthearmedforces.Armieswerenot theonlybranchofthemilitarytobepoliticallyinvolvedandactasagentsof constitutionalchange.Thenavywasasimilarlypoliticizedinstitutionandthe allegianceofthe fleetcouldbecrucialtothesurvivalofaregimeinrepelling invasion.Thiswasmadeclearintheautumnof1688whentheapparentinability ofJamesII’snavytointerceptor fightWilliamofOrange’ s fleetallowedWilliam tolandhisarmyandoverthrowJames.Nevertheless,navieswerelesspolitically dangerousthanarmiessincenaviesweresea-basedratherthanland-basedforces. Unlikenavies,armiescouldcrushbothexternalandinternalthreatstoaregime onlandanditwasinthelatter,potentiallyconstitutionallydevastating,capacity thattheywerefeared.Theperceptionofarmiesaspoliticalgame-changersonly increasedovertheperiod,astheeventsof1659–60,1688,1715,and1745–6 demonstratedtocontemporaries.Noonefeareda ‘standingnavy’ except,perhaps, thetaxpayer;eventhen,taxpayerswerereadilywillingtofundacolossally expensive fleet.Indeed,makingthecomparisonbetweenaconstitutionallydangerousarmyandapatrioticallyvirtuousnavywasanimportantcharacteristicof anti-armysentiment.

The firstthreechaptersofthisbookfocusonCharlesII’stwenty-five-yearreign. DuringthisperiodCharlesconsideredthepossibilityofusinghisnewlycreated armytoenforcehisauthorityinhisongoingcontestwithparliamentoverreligious toleration,royalprerogativepower,foreignpolicy,and,ultimately,thesuccession tohisthrone.YetwhocouldCharlestrusttocommandhisarmy?Hisbrotherand heirpresumptive,James,dukeofYorkandCharles ’seldestillegitimateson,James, dukeofMonmouth,atbitteroddswitheachother,hadtheirownpoliticalagenda; thiswasinseparablefromtheirmilitaryexperience,militaryreputations,and followingwithinCharlesII’sarmy.SincebothYorkandMonmouthlaidclaim tobeingsuccessortoCharlesII’sthrones,theExclusionCrisis,inwhichthose claimsweredebated,occurredwithinacontextinwhichamilitarysolutionwas notinconceivable.

ThedukeofYorksucceededasJamesVIIofScotlandandIIofEnglandon CharlesII’sdeathin1685.Jameswasamilitaryman,deeplyinterestedinarmies. Chapter4analysesJames’splansforandrelationshipwithhisarmyashe embarkedonaschemeofreligiousreformtoentrenchCatholicism.Thechapter exploresthecivil–militarytensionsthatJames’spoliciesgenerated,bothinparliamentand,morewidely,onthestreets.Italsoconsiderstheconspiracywithin James’sarmywhichresultedinthedefectionsofsomearmyofficersandsoldiers toWilliamofOrangein1688,whileothersremainedcommittedtoJames.

ContemporariesfearedJames’smilitarypowerandhowhemightusetroopsto overawehissubjects.ButhowmuchcontroldidJamesactuallyhaveover hisarmy?

OnobtainingtheCrownin1689,WilliamIIIimmediatelylaunchedBritain intotheNineYears’ WarwithFrance.Chapter5examineshowWilliamremodelledthearmytopurgeitofJamesVIIandII’ssupportersand fightthewar.Yet Williamwasnevercertainofhisnewarmy’spoliticalloyalties,nordidhetrustits seniorofficers,someofwhom,suchasJohnChurchill,thefuturedukeof Marlborough,hadbeenkeyplayersintheconspiracytodeserttoWilliamin 1688buthadsoonbecomealienatedfromhim.Jacobitessawmilitarysupport fromwithinthearmyasimportanttoanyattempttorestoretheexiledJamesto histhrones.Furthermore,thelateryearsofWilliamIII’sreignweredominatedby intenseparliamentarydebateabouttheperilsofpeacetimestandingarmies.The Revolutionof1688–9andthewarwithFrancehadfundamentallychangedthe relationshipbetweentheCrownanditssubjects.Butthiswasnotfullyapparentin the1690sandcontemporariesremainedbesetbyfearsoverthearmy’spoliticsand theCrown ’sintentions.

Chapter6exploresthepoliticsofQueenAnne’sarmyassuccessiveministries, withtheCrown ’sbacking,attemptedto ‘model’ thearmytobolstertheirown positionandaims.Theseinitiativeswerenotnovel.Everyregimesince1660had paidcarefulattentiontothepoliticalloyaltiesofthearmy.Norwaspolitical divisionwithinthearmyanewphenomenon.ButAnne’sreign,andthelast fouryearsofitinparticular,representasingularperiodinthepoliticalhistory oftheBritisharmythatreflectthetensionsuniquetothereignofthelastStuart. ThesewereheightenedbytheactivitiesofAnne’scaptain-general,thedukeof Marlborough,theobjectofbothadulationandprofoundsuspicion.Neveragain wouldthearmybesorivenbypartypolitics.Thesuccessiontothethronewas contestedbetweenaProtestantHanoverianclaimantandaJacobiteStuartone. Indeed,inthespringandsummerof1714,acivilwar,accompaniedbyaforeign invasion,waswidelyfeared,fuelledbymemoriesofhowmilitaryactionhad helpedsecureaparticularpoliticalanddynasticoutcomein1660and1688–9.

WhileAnne’sProtestantheir,GeorgeI,succeededpeacefullytothethroneafter thequeen’sdeathin1714,withinayearofhisaccessionhefacedtheJacobite Rebellionof1715.Chapter7examinesdynasticallegiancewithintheearly Georgianarmy.GeorgeIpurgedhisarmyofsuspectedJacobites.ButJacobites stillhopedthatthearmywouldintervenetorestoreJamesVIIandII’sson.Such hopesweremisplaced,forthearmyplayedanenergeticandsometimesdivisive roleinpolicingcommunitieswithareputationfordisaffection.Chapter8examinesrelationsbetweentheCrown,itsministers,parliament,andthearmyinthe ageoftheWhigOligarchy.Fearsofstandingarmiescontinuedtoforman importantpartofoppositiondiscourse,asdidconcernoverthepowerofa militarycommander.Inparticular,GeorgeII’ssonandcaptain-general,the

dukeofCumberland,wasaccusedofaimingatmilitarygovernanceinthelate 1740sandearly1750s.Despitethis,though,thetenorofthedebateoverarmies hadchanged,notonlyasaresultofconstitutionaldevelopmentsbutalsobecause ofmilitaryones.Thearmy’svictoriesintheWaroftheSpanishSuccessionagainst theFrenchhadenhancedbothitsmilitaryandpoliticalreputation,withtheresult thatarmyofficersandsoldierscouldbeconvincinglyviewedasdefendersrather thandestroyersofpoliticalliberties.