AncientRome andVictorian Masculinity

LauraEastlake

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©LauraJoanneEastlake2019

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted

FirstEditionpublishedin2019

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData

Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2018950699

ISBN978–0–19–883303–1

Printedandboundby

CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Acknowledgements

ToChristineFerguson,RhianWilliams,andAndrewRadford thank youforyourtremendousgenerosityandguidanceateverystageofthis project.IwouldalsoliketothankfriendsandcolleaguesfromGlasgow, EdgeHill,andbeyondfortheirfriendshipandintellectualsupportover thepastdecade:SarahBissell,KirstieBlair,AbigailBoucher,Alyson Brown,MatthewCreasy,MargaretForsyth,IsobelHurst,AliceJenkins, JustinLivingstone,AndrewMcInnes,BobNicholson,GideonNisbet, CatherineSteel,HannahTweed,andMollyZiegler.

ThisresearchwasmadepossiblebyanAHRCdoctoralstudentship andanAndrewK.MellonFellowshipattheHarryRansomCentre,for whichIammostgrateful.Iwouldalsoliketothankthewonderfulstaffat theHarryRansomCentreLibrary,whomadesuchusefulrecommendationsduringmyperusaloftheWilkieCollinsandWilsonBarrett archives.IamgratefultoRobertLangenfeldat EnglishLiteraturein Transition andtothe ClassicalReceptionsJournal forpermissionto reproducepartsofthisresearchpreviouslypublishedas ‘Metropolitan Manliness:AncientRome,VictorianLondonandtheRhetoricofthe New,1880–1914’ , EnglishLiteratureinTransition,59.4(2016),473–92 and ‘ForgottenLegaciesofAncientRomeinWilkieCollins’sAntonina’ , ClassicalReceptionsJournal,9.2(2017),193–210.Thanksalsotothe editorsandreviewersatOxfordUniversityPressfortheirtimeandcare inputtingthisvolumetogether.

Asalwaysmymostheartfeltthanksgotomyparents,Helenand David,towhomIowefarmoreloveandgratitudethanIhavewords orspacetoexpresshere;toShirleyandJim thebestgrandparentsand mostwillingreadersanyonecouldaskfor;andtomybrother,Phillip, whoremainstothisdaytheonlypersonwhocandeciphermyacademic shorthand.Finally,tomypartnerDouglasSmall,whoknowsallthe reasonswhy thankyouforeverything.

Contents

ListofIllustrations ix

Introduction1

PartI.ClassicalEducationandManliness intheNineteenthCentury

1.Reading,Reception,andEliteEducation17

2.ImperialBoysandMenofLetters41

PartII.PoliticalMasculinityintheAgeofReform

3.NapoleonicLegaciesandtheReformActof183257

4.Caesar,Cicero,andAnthonyTrollope’sPublicMen83

PartIII.ImperialManliness

5.LiberalImperialismandWilkieCollins’ s Antonina 103

6.NewImperialismandtheProblemofCleopatra133

PartIV.DecadentRomeandLateVictorian Masculinity

7.Rome,London,andCondemningtheMetropolitanMale169

8.TheDecadentImagination:Nero,Pater,andWilde189

Conclusion: ‘BePrepared’—AncientRomeandtheModern Man,1900–18221 Bibliography 229 Index 245

Introduction

RomaandVictoria

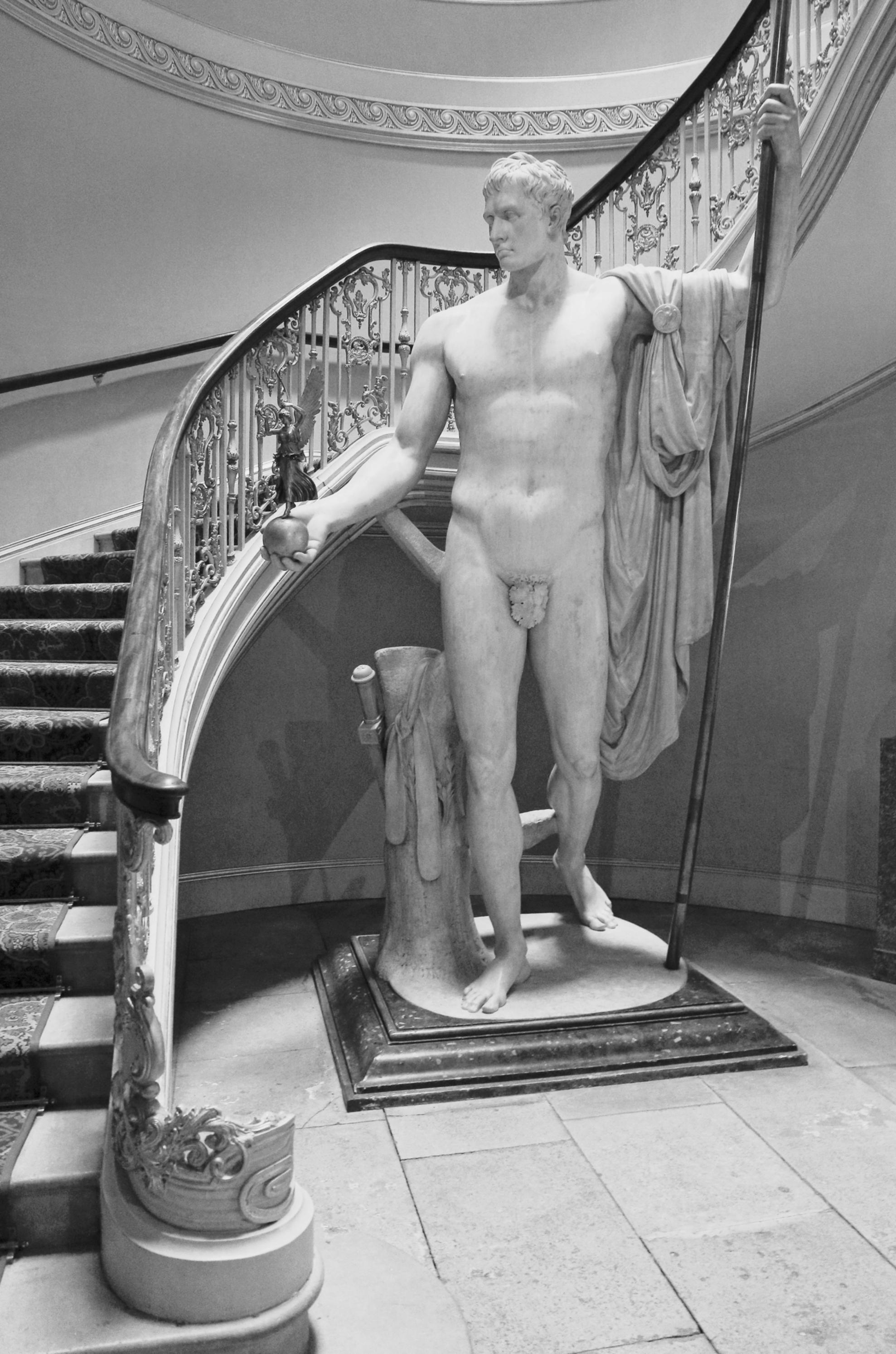

In1816,asthecountrycelebratedthetriumphandmournedthelossesof Waterloo,theBritishnationpresentedtotheDukeofWellingtona statueofNapoleonBonaparteastheRomangodMarsthePeacemaker. PurchasedfromLouisXVIIIfor66,000francs,thestatuebyCanova showstheemperorintheheroicstyleofaclassicalnude,clutchinga wingedVictoryinhisoutstretchedhand(Fig.0.1).Likesomanyworks producedundertheNapoleonicregime,thestatuewasintendedto drawonRomanmythologyandaestheticstoproclaimtheemperora godofwar,whosemartialprowessandmanlyvirtuecouldusherin aneraofpeaceachievedthroughdecisivemilitaryvictory.Itstransferral toWellingtonwasthereforedoublysymbolic.Notonlydiditrepresent thelastlaughforBritainandheralliesagainstNapoleon indeed, Wellington’sfriendsaresaidtohavegleefullyhungtheirumbrellason thesculpturewhentheyvisitedApsleyHouse butitalsosymbolizeda partialyetcrucialreclamationofRomanimageryforBritishmanliness aftermanyyearsofNapoleonicpropagandawhichhadattemptedtocast BritainasaCarthagetoFrance’sRome.

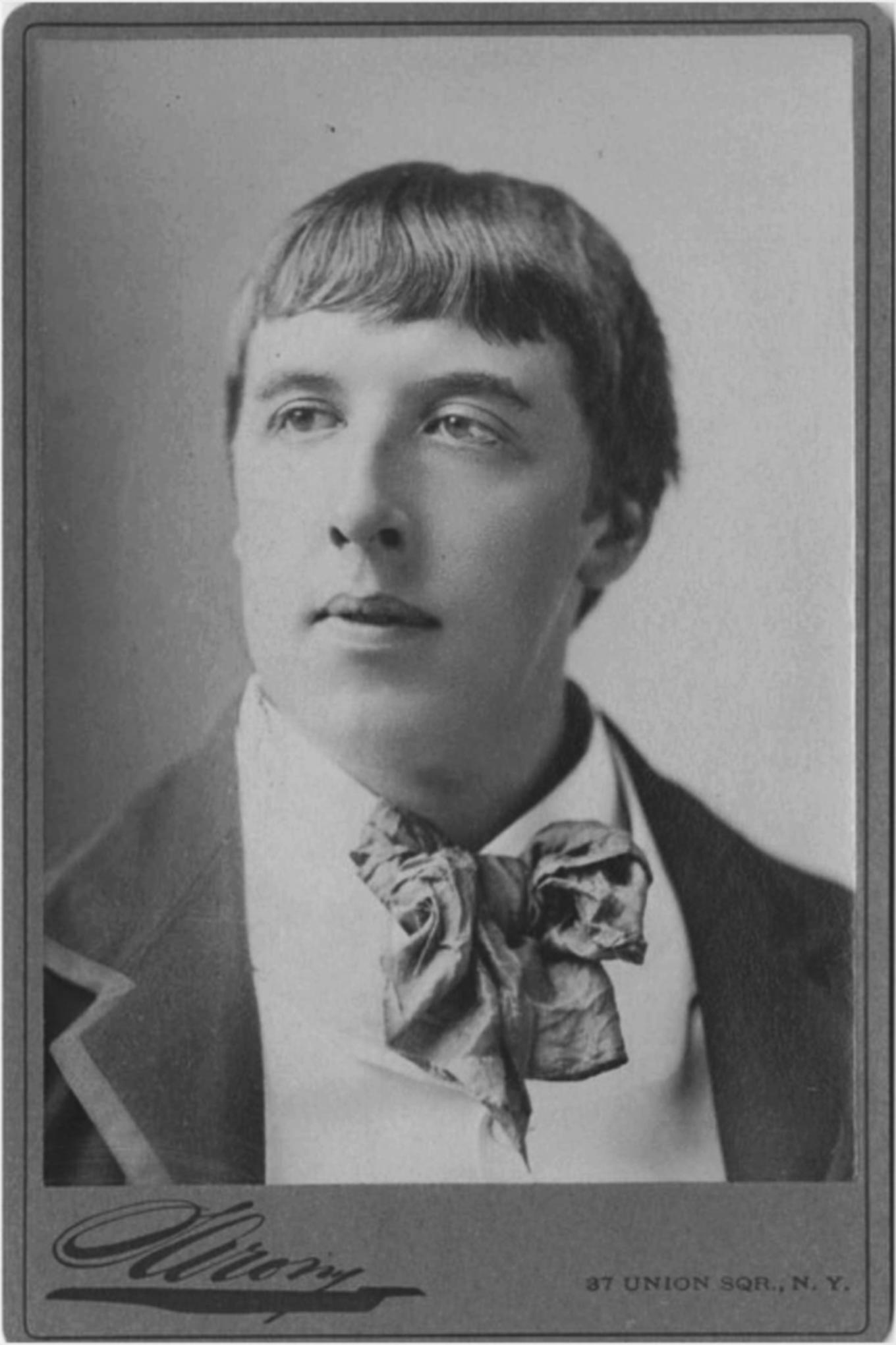

In1883,morethansixty-fiveyearslater,OscarWildereturnedto Americaforthe firsttimesincecompletinghislecturetourtheprevious summer.HedisembarkedfromthesteamshipBritannicnotasaconqueringwarherobut,as TheTimes reported, ‘lookingstouterthanwhen hewaslasthere.Hehashishaircutshortbehindandwearsabangofthe mostpronouncedorder.’¹InthetypicallyplayfulandprovocativefashionoftheDecadencemovement,Wildehadcuthishairintheinthestyle ofRome’smostnotoriousemperor Nero. ‘EverybodytellsmeIlook young;thatisdelightfulofcourse’,WildenotedinalettertoRobert

¹ TheTimes (Philadelphia),August12,1883,p.1.

Fig.0.1. AntonioCanova’ s ‘MarsthePeacemaker’ inthestairwellatApsleyHouse. Publicdomain.

Sherard,andrepeatedasmuchtocelebratedNewYorkphotographer NapoleonSaronywhenhearrivedatSarony’sUnionSquarestudioto havehisportraittaken²(Fig.0.2).

²RobertSherard, OscarWilde:TheStoryofanUnhappyFriendship (London:Hermes Press,1902),p.87.

Fig.0.2. OscarWildewithNeronianHaircut.1883,NewYork.Photographby NapoleonSarony. Publicdomain.

ThoughthesameRomanpastwasusedtocapturethemartialvirtueof Wellingtonaswasusedtoperform(and,bymanycritics,tocondemn) thedecadenceofWilde,thesetwomenbynomeansformabinaryof ‘good’ and ‘deviant’ receptionsoftheancientRomanworld.Rather,they arepartofaconstellationofcomplex,contradictory,andcontinuously

evolvingreceptionsofRome.Overthecourseofthenineteenthcentury Romewasheldupbyvariousindividualsandgroupsasamodelofstoic virtue;ofdangerousrevolutionarysentimentandpopularviolence;of depravedexcessandindulgence;ofbloodthirstinessandbrutality;of paganpersecutionofChristianityaswellastheoriginpointofthe Christianfaith,ofpoeticandaestheticaccomplishment;ofnational prideandhonour;ofimperialsplendour;and,atthesametime,asa warningtaleofimperialdeclineandfall.Thisbookexaminesthese manifoldreceptionsofancientRomeinVictorianliteratureandculture, withaspecificfocusonhowthosereceptionsweredeployedtocreate useablemodelsofmasculinity.

IsuggestthatRomewasmoredeeplyingrainedinthenineteenthcenturymalepsychethanhaspreviouslybeenappreciatedbyascholarly traditionwhichhastendedtochampiontheculturalimportanceof GreeceintheconstructionofVictoriangenderideals.Pioneeringstudies ofVictorianHellenismfromthe1980sincludeRichardJenkyns The VictoriansandAncientGreece (1980)andFrankTurner’ s TheGreek HeritageinVictorianBritain (1981).Impressiveinscaleandscope,these workscharttheinfluenceofGreektexts,aesthetics,philosophy,and evenGreekgodsforVictorianintellectuallife.Theyarealsoinformed byandreinforceanarrativethatwasdeterminedlypromotedbyvarious Victorianinstitutionsandauthorsthemselves,specificallythatancient Greecerepresentedamore fittingmoral,aesthetic,andculturalideal thanhermoreproblematicRomancounterpart.Indeed,ina1989article FrankTurnercouldaskthequestion: ‘WhytheGreeksandNotthe RomansinVictorianBritain?’³Thesuccessorstothisinitialwaveof scholarshipincludeIsobelHurst,ShanynFiske,andTracyOlverson, authorswhoseworksrepurposeearlierstudiesintheclassicaltradition

³FrankTurner, ‘WhytheGreeksandNottheRomansinVictorianBritain?’,in RediscoveringHellenism:TheHellenicInheritanceandtheEnglishImagination, ed.by G.W.Clarke(Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1989),pp.61–81.Workswhich dealwithVictorianreceptionsofclassicalantiquitymorebroadlyinclude:SimonGoldhill, VictorianCultureandClassicalAntiquity:Art,Opera,Fiction,andtheProclamationof Modernity (Oxford:PrincetonUniversityPress,2011)andRichardJenkyns, Dignityand Decadence:VictorianArtandtheClassicalInheritance (London:HarperCollins,1991). WhilstJonathanSachs,in RomanticAntiquity:RomeintheBritishImagination,1789–1832 (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2010)hashelpfullyre-examinedRomanticusesofRome, NormanVance’ s, TheVictoriansandAncientRome (Oxford:Blackwell,1997)remainsthe onlyextensivecriticalappraisalofRome,asdistinctfromGreece,intheVictorianperiod.

andVictorianreceptionsofGreece,todiscussnineteenth-centuryfemininity.⁴ YetwhilecriticaldiscussionofVictorianHellenismhasexpandedtoencompassthequestionofgender,scholarshiponRomehasremainedrelatively static.NormanVance’ s TheVictoriansandAncientRome (1997)remains theonlymajorstudytodealexclusivelywiththeRomaninheritancein Victorianliteratureandculture.ThisbookbuildsonVance’sstudy,applying toRomeandtoVictorianmasculinitiesthesamereassessmentinlightof classicalreceptionandgenderstudiesthatHurstandothers,buildingon Jenkyns,broughttoGreeceandnineteenth-centuryfemininity.Whilstthere iscertainlyatraditionofVictorianculture’ sconflatingGreekandRoman pastsaspartofamoregeneralnotionofclassicalantiquity,thisbookshows thatRomecouldalsorepresentauniquesetofmeanings(andproblems)for Victorianculture andparticularlyfornotionsofVictorianmasculinity whichmakeitworthstudyinginitsownright.

MasculinityandReception

TheVictorianagewaspreoccupiedwithwhatwenowcallissuesof reception.Intheintroductiontohis HistoryofRome (1838),Thomas ArnoldcapturedasenseofearlyVictorianoptimismaboutthespiritof hisownage,butalsoidentifiedwhathefeltwastheprivilegedinsightof theVictorianmaleintotheancientRomanworld:

Wehavelivedinaperiodrichinhistoricallessonsbeyondallformerexample;we havewitnessedoneofthegreatseasonsofmovementinthelifeofmankind,in whichtheartsofpeaceandwar,politicalpartiesandprinciples,philosophyand religion,inalltheirmanifoldformsandinfluences,havebeendevelopedwithan extraordinaryforceandfreedom.Ourownexperiencehasthusthrownabright lightupontheremoterpast ⁵

Agreatempirical,imperial,utilitarianpresentprovidedArnold’ sgenerationwithbothanimpetusandalensthroughwhichtoviewtheancient past. ‘Muchwhichourfatherscouldnotfullyunderstand,frombeing

⁴ SeeIsobelHurst, VictorianWomenWritersandtheClassics:theFeminineofHomer (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2006);ShanynFiske, HereticalHellenism:Women Writers,AncientGreece,andtheVictorianPopularImagination (Athens:OhioUniversity Press,2008);TracyOlverson, WomenWritersandtheDarkSideofLate-Victorian Hellenism (Basingstoke:PalgraveMacmillan,2010).

⁵ ThomasArnold, HistoryofRome,3vols(London:B.Fellowesetal.,1845),I:vi–vii.

accustomedonlytoquietertimes’,hewrites, ‘istousperfectlyfamiliar.’⁶ AndArnoldwasnotaloneincelebratingwhatPeterAllanDalecallsthe ‘nineteenth-centuryphenomenonofhistorical-mindedness’ ⁷ In1842 JohnStuartMillnotedthat: ‘Theideaofcomparingone’sownagewith formerages,orwithournotionofthosewhichareyettocome,had occurredtophilosophers;butitneverbeforewasthedominantideaof anyage.’⁸ Mill’swordscapturewhatseemsanextraordinaryawarenessof theinherentself-reflexivitywhichgovernsanyencounterwithatextor artefactfromthepast.AsGadamerwrites: ‘tounderstandwhataworkof artsaystousis aself-encounter’ ; ⁹ howonerespondstoandutilizesa pastlikeancientRomeconstitutesareflectionnotonlyonthespiritof theagebut,potentially,onthenature,values,andideologiesofthe individual.

ThomasMacaulay’ s LaysofAncientRome (1842)offersperhapsthe clearestexampleoftheself-reflexivityofVictorianencounterswiththe ancientRomanpast.Thoughpublishedinthe1840s,Macaulaystarted writingthe Lays inthesummerof1834and,asWilliamMcKelvynotes, thepoemswere ‘aboutthedividendsofliberalreform intheancient andmodernworlds ... Macaulayofferedthepartnersofwhatwould becomeknownastheVictoriancompromiseareassuringhistorical analogywhichfavouredreligioustolerationandanexpandedfranchise.’¹⁰

The Lays arecomprisedoffourpoemswithmaterialdrawnfrom Livy’shistoriesofearlyRome,butframedasimaginedexamplesof whatMacaulay followingNiebuhr claimedwasanearlier,losttraditionofLatinballadpoetryonthesamesubjects. ‘Horatius’ recounts thestoryofHoratiusCoclesandhisdefenceofthePonsSubliciusagainst anEtruscanattackin514 . ‘TheBattleofLakeRegillus’ describes thedefeatofaLatinarmyin496 withthehelpofmythologicaltwins CastorandPollux,whoarriveto fightfortheRomancause. ‘Virginia’

⁶ Arnold, HistoryofRome,p.vii.

⁷ PeterAllanDale, TheVictorianCriticandtheIdeaofHistory (London:Harvard UniversityPress,1977),p.3.

⁸ JohnStuartMill, ‘TheSpiritoftheAge’ , Examiner,3615(January9,1831),pp.20–1(p.20).

⁹ Hans-GeorgGadamer, PhilosophicalHermeneutics,trans.byDavidR.Linge(London: UniversityofCalifornia,1976),p.101.

¹

⁰ WilliamR.McKelvy, ‘PrimitiveBallads,ModernCriticism,AncientSkepticism: Macaulay’sLaysofAncientRome’ , VictorianLiteratureandCulture,28.2(2000), pp.287–309(p.293).

dealswitheventswritteninLivy3.44–50inwhichanattackonthe plebeiangirlVirginiabythepatricianAppiusClaudiusin449 results inherbeingkilledbyherfatherinordertopreserveherfrombeing unjustlyclaimedasClaudius’ slave.ThedeathofVirginiaalsocatalysesa crisisofclassconflictand,ultimately,resultsinconstitutionalreform withtheLicinianLaws,andtheenshrininginlawofsafeguardswhich enfranchiseandprotectthepeoplefrompatricianexploitation.The final lay, ‘TheProphecyofCapys’ takesusbackwards,ratherthanforwardsin time,describingaprophecygiventoRomulusin753 of ‘Rome’sfuture greatness’ andher ‘vastempire’ whichshallspread ‘overtheknown world’.¹¹Macaulaylookstotheearly,foundingdaysofRomeinorder toprojectavisionoffutureimperialgreatnesswhich,asanyVictorian readerwouldknow,resultedinthespreadoftheRomanEmpireoverthe nextthousandyears.Accordingtothelogicofthe Lays,agreatempireis therewardnotonlyforthedefenceofone’sstateagainstaggressorsbut, justassignificantly,forconstitutionalreformandthecultivationofvalour andliberalmasculinevirtuesamongthenation’ smen. ‘TheoldRomans hadsomegreatvirtues,’ Macaulaywritesinhisintroductiontothetext; ‘fortitude,temperance,veracity,spirittoresistoppression,respectfor legitimateauthority, fidelityintheobservingofcontracts,disinterestedness,ardentpatriotism.’¹²HoratiusCoclesisinmanywaystheembodimentofthesevirtuesandanheirtoanevenoldergenerationofvenerable Romanstatesmen:

THENNONEWASforaparty; Thenallwereforthestate; Thenthegreatmanhelpedthepoor, Andthepoormanlovedthegreat: Thenlandswerefairlyportioned; Thenspoilswerefairlysold: TheRomanswerelikebrothers Inthebravedaysofold.¹³

Thisspeech,withitsemphasisonfairerdistributionoflandandwealth, echoesstronglytherhetoricofpoliticalreformforwhichMacaulay

¹¹ThomasBabingtonMacaulay, TheLaysofAncientRome (London:Longman,Brown, Green,andLongmans,1842),pp.144,146,147.

¹²Macaulay, ‘Introduction’,in Lays,p.22.

¹³Macaulay, Lays,p.38.

himselfisbestremembered.Suchvalues,the Lays suggests,areenshrined intheveryfoundingprinciplesofearlyRome,butthecontinuedgreatnessofRomeasasociety and,byextension,asthegreatempireshewill onedaybecome isdependentuponthewillingnessofhermalecitizens tobemanlyandtotakeactioninthenameofcivicduty.Onesuchcall formasculineactionismadebyVirginia’sbetrothedIcilius: ‘Nowby yourchildren’scradles,nowbyyourfathers’ graves,/Bementoday, Quirites,orbeforeverslaves!’¹⁴ Themalecitizen’spatriotic(though undoubtedlypaternalistic)defenceoffatherlandandfamily,ofnational anddomesticvalues,aswellaspoliticalresistancetothehegemonyofa landedaristocracy,areallsubtextsencodedintothereferencetofathers andchildreninthispassage.Theyaredesignatedasidealizedvaluesby whichnineteenth-centuryreaderstoocould ‘bemen’.Conversely,they establishanimplicitdemotion,evenanindictment,ofmenwhodonot sharesuchviews: ‘slaves ’,inMacaulay’sformulationofpoliticalmanliness,suggestsdisenfranchisementandexclusionfromallaccesstocivic virtue.Macaulay,writinginthe1830s,alsomakesthesubtleequation betweenbeingonthe ‘ wrong ’ sideofthereformdebatewithbeingofthe wrongsideofabolitionistdebateswhichhadoccurredadecadeearlier andresultedintheAbolitionActof1833,endingslaverythroughout theBritishEmpire.TheBritishmaleandtheBritishEmpireitselfare setupinthe Lays astheheirstoRomanheroeslikeHoratiusandto theRomanEmpire.ThroughreferencetoRomeMacaulayiscompilinga pastforwhatheconsiderstobethespiritandvaluesofhisownage. ThisretrospectivereplantingoftherootsofVictorianidentityalso createsanimaginedgenealogyofpoliticalmanlinessandestablishes theVictorianreformerastheheiroftheRomanherofrom ‘thebrave daysofold’.ItisaprimeexampleofwhatCharlesMartindaleterms the ‘two-way ... dialogue’ betweenpastandpresent.¹⁵ Macaulayevengoessofarastodrawattentiontothisprocessof receptioninactionbyincludinginthevolumeanintroductiontoeach poemandanimaginedperformancehistoryforeach. ‘TheBattleofLake Regillus’,forexample,issetin496 ,butwascomposed,Macaulaytells

¹⁴ Macaulay, Lays,pp.111–12.

¹⁵ CharlesMartindale, ‘Reception’,in ACompaniontotheClassicalTradition,ed.by CraigKallendorf(Oxford:Blackwell,2007),pp.297–311(p.298).

usaround303 , ‘aboutninetyyearsafterthelayorHoratius’,¹⁶ forthe occasionofaredistributionofpoweramongRome’sequestrianclassand thesubsequentequestriancelebrationsinhonourofCastorandPollux. Macaulaygivesequalattentiontotheeventsofthepoemastothe imaginedcontextinwhichthepoemwascomposedandperformed, thelatterbearingmorethanapassingresemblancetothepolitical climateofBritaininanageofreform:

Itbecameabsolutelynecessarythattheclassificationsofthecitizensshouldbe revised.Onthatclassificationdependedthedistributionofpoliticalpower.Partyspiritranhigh;andtherepublicseemedtobeindangeroffallingunderthe dominioneitherofanarrowoligarchyorofanignorantandhead-strongrabble.¹

MacaulayoffersusnotmerelyastraightforwardreceptionofLivy’ s works,butadramatizationofreceptioninactionandonewhichplaces theperformanceofpoetryattheheartofnationalandpoliticalheroism. Thepoems,withtheirimaginedoriginstories,historiographicaltraditionsandperformancehistoriesforthemythologicalmaterialfoundin Livy,heroizenotonlytheancientwarriorslikeHoratiusbutalsothe contributionofstatesmenandpoetstotheforgingofgreatnationsand greatempires.The Lays representwhatIpositisauniversaltensionin VictorianwritingaboutRome,wherebytheactofreceptionitselfis necessarily,andoftenknowingly,madetofunctionaspartofanarticulationorvalidationofaparticularmasculineideal.

Despitetheself-confidentbombastofArnold,Mill,andevenMacaulay onthemodernityandliberalityoftheage,thenineteenthcenturyalso experiencedunprecedentedsocial,cultural,andeducationalchanges whichresultedinthefragmentingofmasculineidentities.AsChristopher Straynotesin ClassicsTransformed (1998),theabilitytotakeone’splace asanadultmaleinthemiddleandupperranksofVictoriansocietywas largelypredicatedonthelearningofclassicallanguages.Latinwasa pre-requisiteforentryintouniversities,militarycolleges,andcareersin publicservice,thechurch,andthelaw.Aclassicaleducation ‘operated togivestyle,asenseofbelonging,andaninstrumentforthemarking andexcludingofoutsiders’.¹⁸ Yettheperiodcoveredbythisbookalso

¹⁶ Macaulay, Lays,p.53.¹⁷ Macaulay, Lays,p.59.

¹⁸ ChristopherStray, ClassicsTransformed:Schools,Universities,andSocietyinEngland, 1830–1960 (Oxford:ClarendonPress,1998),p.31.

witnessedsignificantcritiqueandreformoftraditionalclassicaleducation forboys.Socio-culturalchange;thegrowingpowerofthemiddleclasses; theriseofnewindustries;theincreasingavailabilityofclassicalliterature intranslationandinnewprintmedia;aswellastheprofessionalization ofknowledgeintonewcareertracksformenresultedinever-increasing callsforbroaderandmorepracticaleducationforboyswhichwould preparethemforthetrialsandrealitiesofmodernlife.Theveryfactors whichproducedreformintheclassicalcurriculumforboysalsocontributedtothepluralizingorfragmentingofmasculineidentitiesandaneed torenegotiatemasculinehierarchiesbasedoncriteriaasdiverseas commercialorliterarysuccess,physicalprowess,domesticvalues,aesthetictastes,andreligiousorcivicvirtue.

Indeed,withtheemergenceofmasculinitystudiesasadisciplineinthe 1990s,workslikeHerbertSussman’ s VictorianMasculinities (1995), JamesEliAdams’ s DandiesandDesertSaints (1995),JohnTosh’ s A Man’sPlace (1999),andAndrewDowling’ s ManlinessandtheMale Novelist (2001)havebeeninvaluableforestablishinghowsuchmasculineidentitiesastheManofLetters,theimperialist,andthedecadent wereconceptualizedandcodified.Masculinitystudieshasalsodone muchtocomplicateconventionalfeministunderstandingsofVictorian patriarchy,bystressingtheinternalconflictsandcriseswhichexistedin nineteenth-centurymaleculture.AsHerbertSussmannotes,Victorian masculinityexisted:

Notasaconsensualorunitaryformation,butratheras fluidandshifting,asetof contradictionsandanxietiessoirreconcilablewithinmalelifeinthepresentasto beharmonizedonlythrough fictiveprojectionsintothepast,thefutureoreven theafterlife.¹⁹

OfallthepaststowhichSussmanrefers,ancientRomewasoneofthe mosthotlycontested.ThiswasprimarilybecausetheRomanlegacy encompassedinnumerableandoftencompetingnarrativesandmeanings,signifyingeverythingfromtheloftiestheightsofcivicandmilitary manliness,todecadence,degeneration,andeffeminacy.EvenMacaulay’ s Lays,which,aswehaveseen,encapsulatedadistinctbrandofliberal imperialmanlinessandcivicvirtueatthetimeofitsproduction,

¹⁹ HerbertSussman, VictorianMasculinities:ManhoodandMasculinePoeticsinEarly VictorianLiteratureandArt (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1995),pp.2–3.

acquirednoticeablydifferentmeaningsasthecenturyworeon.During the1860sthe Lays werethesubjectofhostileattentionsfromMatthew Arnold,whodismissedtheirformalandaestheticmeritswhenhe claimedthat: ‘Aman’spowertodetecttheringoffalsemetalinthose Laysisagoodmeasureofhis fitnesstogiveanopinionaboutpoetical mattersatall.’²⁰ Arnoldmakesscathinglyexplicittheideathatwhatisat stakeintheinterconnectedtasksofclassicalreceptionandtheproductionofpoetryisabroaderquestionofmasculinityandaman’sperceived powertoclaimculturalauthorityinhisownage.However,hisdismissal seemstohavedonenopermanentdamagetothereputationandsalesof Macaulay’spoems.Insteadbytheendofthecenturythe Lays were amongthehighestsellingpoeticworksoftheera,althoughtheirprimary readershipwasnolongerstatesmenandreformersbut,overwhelmingly, schoolboys. ‘[W]ecanimaginethe Lays beingreadin1908sidebyside withBadenPowell’ s ScoutingforBoys’,²¹McKelvynotes.Thechanging politicalclimate,alterededucationalgoals,and,mostimportantly,the shiftinthecharacteroftheBritishempirefromaliberalimperialproject inthe firsthalfofthecentury,withitspaternalisticnarrativesofthe civilizingmissionofempire,toamorerobustlyexpansionistNew Imperialistprojectfromthe1870s,meantthatthephysicalcourage andcombativenationalismofMacaulay’sRomanscametooutweigh theirreformingzealforanewgenerationofimperialboys.Theprecise meaningofRomeforVictorianculture,then,wasnomore fixedandno morestablethanthemeaningofmasculinityitself.

Inthiscontext,themultifariousandoftencontradictorytreatmentsof theRomanexampleinVictorianliteraturefromWaterlootoWildeand frompoliticalreformtoimperialexpansionmakesenseaspartofan overarchingthesisonnineteenth-centurycodificationsofmasculinity. UnderstandingRomeasacontestedspace,withanarrayofpossible scriptsandnarrativesthatcouldbeharnessedtoframemodelsof masculineideality,ortovilifyperceiveddeviancefromthoseideals, allowsforanunderstandingofmasculinityasbeingrootedinthe powerofreception.IpresentamodelofVictorianmasculinitywherein masculinedominance,whetherindividualorcollective,isderivedfrom ²⁰ MatthewArnold, TheCompleteWorksofMatthewArnold,ed.byR.H.Super,11vols (AnnArbor:UniversityofMichiganPress,1960–77),I:211.

²¹McKelvy, ‘PrimitiveBallads’,p.288.

theperceivedauthoritytoassignmeaningtoRomeasanimage,andto determineitsusageeitherasabadgeofmeritoracondemnationof certaingenderedtraits.Thusdowe findnineteenth-centuryconflictsor crisesofmasculinity,suchastheantagonisticrelationshipbetweenthe NewImperialistandthedandyof fin-de-siècleculture,manifestingasa struggleoverauthoritativeusesoftheRomanparallel.Thechaptersthat followareorganizedtoshowhowRomewasusedtoconceptualizeand codifydifferent ‘styles’ ofmanlinessinavarietyofliteraryandcultural contexts,andinlightofnineteenth-centurydiscoursesoneducation, reform,colonialism,anddegeneration.

Part1exploresthewaysthatVictorianboyswereexposedtothe history,narratives,andliterarytextsofancientRome.Iexaminethe relationshipbetweenactsofchildhoodreadingandtheinculcationof genderandclassvaluestoshowhowRomewascentraltotheforgingof elitemaleconsciousnessandidentityatbothanindividualandcollective level.RomancultureandtheLatinlanguagesuppliedmiddle-andupperclassboyswithanetworkofreferenceswithwhichtheycouldframeall mannerofconflictandalliance,eveninanageinwhichnewprofessions meantthattherelevanceofclassicsinthecurriculumwasincreasingly underquestion.Chapter2, ‘ImperialBoysandMenofLetters’ looksto schoolboy fictionssuchasThomasHughes’ s TomBrown’sSchooldays (1857),F.W.Farrar ’ s Eric;orLittleByLittle (1858),andRudyard Kipling’ s StalkyandCo. (1899)todemonstratehowRomewasusedto fosterrobustmanlinessoftheimperialisttype,butalsoits(oftenoverlooked)intellectualequivalent theManofLetters.

Part2, ‘PoliticalMasculinityintheAgeofReform’,examinesthe ideologicalimportanceofRomeforcreatingnon-violentmodelsof politicalauthority.Iaccountfortheseeminglyanomaloushesitanceof themaleelitesdiscussedinthepreviouschaptertodrawcomparisons withancientRomeintheparliamentarydebatesofthe1830s.Political receptionsofRomeareshowntobecomplicatedandevenradicalizedin theageofreformbyFrenchrevolutionaryandNapoleonicusesofthis sameRomanpast.Bythe1860sand1870s,however,thereemergeda growingfrustrationwiththesupposedtimidityofpoliticalelitesto engagewiththeRomanpast,andIcharttheeagerbutbynomeans uncomplicatedre-engagementofwriterslikeAnthonyTrollopewith Romeasameansofframingpartisanpoliticalideologies.

Part3canvassessomeofthemajorculturalintersectionsbetween empire,masculinity,andtheclassicaltraditiontoaccountforwhy,in

theNewImperialistdiscourseofthe1880sonwards,ithadbecome difficulttospeakofempireandtheassociatedmodelsofhardyimperial manlinesswithoutrecoursetotheRomanparallel.Isituatethisproblem inthecontextoflargertransformationsinthenatureoftheBritishEmpire fromanaval,commercialenterprise forwhichancientGreeceandthe Athenianempireprovedamore fittingparallel toanexpansionistlandbasedprojectwhichdrewincreasinglyonRomanmodels.

Part4examinestheusesofdecadentRomein fin-de-sièclediscoursesofaestheticismanddecadencetoaccountfortheanxious, evenantagonistic,relationshipbetweentheNewImperialistmaleand thedandy figureinlatenineteenth-centuryculture.Chapter7,entitled ‘Rome,London,andCondemningtheMetropolitanMale’,dealswith hostile,conservativediscourseswhichdrewonnarrativesofdecadent Romeandthedeclineandfallofempiretocondemnthenewurban malewho,unlikehishardlyimperialistcounterparts,seemedto embodygrowingfearsaboutdevianceanddegeneracyatthe finde siècle.The finalchapter, ‘TheDecadentImagination:Nero,Pater,and Wilde’,examinesthesefearsfromtheothersideofthedebate,showing howwriterslikeWalterPater,OscarWilde,andGeorgeBernardShaw, bydrawingontheverysameparallelsastheirconservativedetractors, wereinvestedinconstructingrevisionistcounternarrativestothe Gibbonianmodelof ‘declineandfall’,andespeciallyofdeclineand fallasbeingcatalysedbydecadent(andthereforefailedordiseased) masculinevigour.

ByunderstandingVictorianreceptionsofRomeasbeinginherently boundupwithquestionsofmasculinity,wecanbetteraccountforthe manifoldandoftencontradictorymanifestationsofRomeinVictorian writingwhereRomansappearsimultaneouslyaspaganpersecutors, piousstatesmen,pleasure-seekingdecadents,andheroesofempire. Understoodthroughthelensofmasculinity,Victorianreceptionsof Romebecomemorecomprehensible:Romeiscontestedbecausemasculinityiscontested.TherearemanycompetingvisionsofRomebecause therearemanycompetingstylesofmasculinity.Farfromattemptingto artificiallyhomogenizeortoimposeasingularnarrativeofVictorian reception,theaimofthisbookistoexploreitscomplexityandtoexplain itscentralconflictasastruggleoverthecodificationofmanliness wherebytheculturalauthoritytoassignmeaningtotheRomanageis equivalenttoandindicativeofthepowertospeakauthoritativelyabout masculinityinthepresent.