ANINTRODUCTIONTO Thermal Physics

DanielV.Schroeder

WeberStateUniversity

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford, OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

c DanielSchroeder2021

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted Impression:1

Originallypublishedin1999byAddisonWesleyLongman

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2020946666

ISBN978–0–19–289554–7(hbk.) ISBN978–0–19–289555–4(pbk.) DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192895547.001.0001

PrintedandboundintheUKby TJBooksLimited

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Preface

Thermalphysics dealswithcollectionsof large numbersofparticles—typically 1023 orso.Examplesincludetheairinaballoon,thewaterinalake,theelectrons inachunkofmetal,andthephotons(electromagneticwavepackets)giveno⇧ by thesun.Anythingbigenoughtoseewithoureyes(orevenwithaconventional microscope)hasenoughparticlesinittoqualifyasasubjectofthermalphysics.

Considerachunkofmetal,containingperhaps1023 ionsand1023 conduction electrons.Wecan’tpossiblyfolloweverydetailofthemotionsofalltheseparticles, norwouldwewanttoifwecould.Soinstead,inthermalphysics,weassume thattheparticlesjustjostleaboutrandomly,andweusethelawsofprobability topredicthowthechunkofmetalasawholeoughttobehave.Alternatively,we canmeasurethebulkpropertiesofthemetal(sti⇧ness,conductivity,heatcapacity, magnetization,andsoon),andfromtheseinfersomethingabouttheparticlesitis madeof.

Someofthepropertiesofbulkmatterdon’treallydependonthemicroscopic detailsofatomicphysics.Heatalwaysflowsspontaneouslyfromahotobjecttoa coldone,nevertheotherway.Liquidsalwaysboilmorereadilyatlowerpressure. Themaximumpossiblee⌃ciencyofanengine,workingoveragiventemperature range,isthesamewhethertheengineusessteamorairoranythingelseasits workingsubstance.Thesekindsofresults,andtheprinciplesthatgeneralizethem, compriseasubjectcalled thermodynamics

Buttounderstandmatterinmoredetail,wemustalsotakeintoaccountboth thequantumbehaviorofatomsandthelawsofstatisticsthatmaketheconnection betweenone atomand1023 .Thenwecannotonly predict thepropertiesofmetals andothermaterials,butalsoexplain why theprinciplesofthermodynamicsare whattheyare—whyheatflowsfromhottocold,forexample.Thisunderlying explanationofthermodynamics,andthemanyapplicationsthatcomealongwith it,compriseasubjectcalled statisticalmechanics

Physicsinstructorsandtextbookauthorsareinbitterdisagreementoverthe propercontentofafirstcourseinthermalphysics.Someprefertocoveronly thermodynamics,itbeinglessmathematicallydemandingandmorereadilyapplied totheeverydayworld.Othersputastrongemphasisonstatisticalmechanics,with

itsspectacularlydetailedpredictionsandconcretefoundationinatomicphysics. Tosomeextentthechoicedependsonwhatapplicationareasonehasinmind: Thermodynamicsisoftensu⌃cientinengineeringorearthscience,whilestatistical mechanicsisessentialinsolidstatephysicsorastrophysics.

InthisbookIhavetriedtodojusticeto both thermodynamicsandstatistical mechanics,withoutgivingundueemphasistoeither.Thebookisinthreeparts. PartIintroducesthefundamentalprinciplesofthermalphysics(theso-calledfirst andsecondlaws)inaunifiedway,goingbackandforthbetweenthemicroscopic (statistical)andmacroscopic(thermodynamic)viewpoints.Thisportionofthe bookalsoappliestheseprinciplestoafewsimplethermodynamicsystems,chosen fortheirillustrativecharacter.PartsIIandIIIthendevelopmoresophisticated techniquestotreatfurtherapplicationsofthermodynamicsandstatisticalmechanics,respectively.Myhopeisthatthisorganizationalplanwillaccommodatea varietyofteachingphilosophiesinthemiddleofthethermo-to-statmechcontinuum.Instructorswhoareentrenchedatoneortheotherextremeshouldlookfor adi⇧erentbook.

Thethrillofthermalphysicscomesfromusingittounderstandtheworldwe livein.Indeed,thermalphysicshasso many applicationsthatnosingleauthor canpossiblybeanexpertonallofthem.InwritingthisbookI’vetriedtolearn andincludeasmanyapplicationsaspossible,tosuchdiverseareasaschemistry, biology,geology,meteorology,environmentalscience,engineering,low-temperature physics,solidstatephysics,astrophysics,andcosmology.I’msuretherearemany fascinatingapplicationsthatI’vemissed.Butinmymind,abooklikethisone cannothavetoomanyapplications.Undergraduatephysicsstudentscananddogo ontospecialize inallofthesubjectsjustnamed,soIconsideritmydutytomake youawareofsomeofthepossibilities.Evenifyouchooseacareerentirelyoutside ofthesciences,anunderstandingofthermalphysicswillenrichtheexperiencesof everydayofyourlife.

Oneofmygoalsinwritingthisbookwastokeepitshortenoughforaonesemestercourse.Ihavefailed.Toomanytopicshavemadetheirwayintothe text,anditisnowtoolongevenforaveryfast-pacedsemester.Thebookisstill intendedprimarily for aone-semestercourse,however.Justbesuretoomitseveral sectionssoyou’llhavetimetocoverwhatyou do coverinsomedepth.Inmy owncourseI’vebeenomittingSections1.7,4.3,4.4,5.4through5.6,andallof Chapter8.ManyotherportionsofPartsIIandIIImakeequallygoodcandidates foromission,dependingontheemphasisofthecourse.Ifyou’reluckyenoughto have more thanonesemester,thenyoucancoverallofthemaintextand/orwork someextraproblems.

Listeningtorecordingswon’tteachyoutoplaypiano(thoughitcanhelp), andreadingatextbookwon’tteachyouphysics(thoughittoocanhelp).To encourageyoutolearnactivelywhileusingthisbook,thepublisherhasprovided amplemarginsforyournotes,questions,andobjections.Iurgeyoutoreadwith apencil(notahighlighter).Evenmoreimportantaretheproblems.Allphysics textbookauthorstelltheirreaderstoworktheproblems,andIherebydothesame. Inthisbookyou’llencounterproblemseveryfewpages,attheendofalmostevery

section.I’veputthemthere(ratherthanattheendsofthechapters)togetyour attention,toshowyouateveryopportunitywhatyou’renowcapableofdoing.The problemscomeinalltypes:thoughtquestions,shortnumericalcalculations,orderof-magnitudeestimates,derivations,extensionsofthetheory,newapplications,and extendedprojects.Thetimerequiredperproblemvariesbymorethanthreeorders ofmagnitude.Pleaseworkasmanyproblemsasyoucan,earlyandoften.You won’thavetimetoworkallofthem,butplease read themallanyway,soyou’ll knowwhatyou’remissing.Yearslater,whenthemoodstrikesyou,gobackand worksomeoftheproblemsyouskippedthefirsttimearound.

Beforereadingthisbookyoushouldhavetakenayear-longintroductoryphysics courseandayearofcalculus.Ifyourintroductorycoursedidnotincludeany thermalphysicsyoushouldspendsomeextratimestudyingChapter1.Ifyour introductorycoursedidnotincludeanyquantumphysicsyou’llwanttoreferto AppendixAasnecessarywhilereadingChapters2,6,and7.Multivariablecalculus isintroducedinstagesasthebookgoeson;acourseinthissubjectwouldbea helpful,butnotabsolutelynecessary,corequisite.

Somereaderswillbedisappointedthatthisbookdoesnotcovercertaintopics, andcoversothersonlysuperficially.AsapartialremedyIhaveprovidedanannotatedlistofsuggestedfurtherreadingsatthebackofthebook.Anumberof referencesonparticulartopicsaregiveninthetextaswell.ExceptwhenIhave borrowedsomedataoranillustration,Ihavenotincludedanyreferencesmerely togivecreditto theoriginatorsofanidea.Iamutterlyunqualifiedtodetermine whodeservescreditinanycase.Theoccasionalhistoricalcommentsinthetext aregrosslyoversimplified,intendedtotellhowthings could havehappened,not necessarilyhowtheydidhappen.

Notextbookisevertrulyfinishedasitgoestopress,andthisoneisnoexception.Fortunately,theWorld-WideWebgivesauthorsachancetocontinually provideupdates.Fortheforeseeablefuture,thewebsiteforthisbookwillbeat http://physics.weber.edu/thermal/.Thereyouwillfindavarietyoffurther informationincludingalistoferrorsandcorrections,platform-specifichintson solvingproblemsrequiringacomputer,andadditionalreferencesandlinks.You’ll alsofindmye-mailaddress,towhichyouarewelcometosendquestions,comments, andsuggestions.

Acknowledgments

Itisapleasuretothankthemanypeoplewhohavecontributedtothisproject. Firsttherearethebrilliantteacherswhohelpedmelearnthermalphysics:Philip Wojak,TomMoore,BruceThomas,andMichaelPeskin.TomandMichaelhave continuedtoteachmeonaregularbasistothisday,andIamsincerelygratefulfor theseongoingcollaborations.Inteachingthermalphysicsmyself,Ihaveespecially dependedontheinsightfultextbooksofCharlesKittel,HerbertKroemer,andKeith Stowe.

Asthismanuscriptdeveloped,severalbravecolleagueshelpedbytestingitin theclassroom:ChuckAdler,JoelCannon,BradCarroll,PhilFraundorf,Joseph Ganem,DavidLowe,JuanRodriguez,andDanielWilkins.Iamindebtedtoeachof

them,andtotheirstudents,forenduringthemanyinconveniencesofanunfinished textbook.Iowespecialthankstomyownstudentsfromsevenyearsofteaching thermalphysicsatGrinnellCollegeandWeberStateUniversity.I’mtemptedto listalltheirnameshere,butinsteadletmechoosejustthreetorepresentthem all:ShannonCorona,DanDolan,andMikeShay,whosequestionspushedmeto developnewapproachestoimportantpartsofthematerial.

Otherswhogenerouslytookthetimetoreadandcommentonearlydrafts ofthemanuscriptwereEliseAlbert,W.Ariyasinghe,CharlesEbner,Alexander Fetter,HarveyGould,Ying-ChengLai,TomMoore,RobertPelcovits,Michael Peskin,AndrewRutenberg,DanielStyer,andLarryTankersley.FarhangAmiri, LeeBadger,andAdolphYonkeeprovidedessentialfeedbackonindividualchapters, whileColinInglefield,DanielPierce,SpencerSeager,andJohnSohlprovidedexpert assistancewithspecifictechnicalissues.KarenThurberdrewthemagicianand rabbitforFigures1.15,5.1,and5.9.Iamgratefultoalloftheseindividuals,and tothedozensofotherswhohaveansweredquestions,pointedtoreferences,and givenpermissiontoreproducetheirwork.

Ithankthefaculty,sta⇧,andadministrationofWeberStateUniversity,forprovidingsupportinamultitudeofforms,andespeciallyforcreatinganenvironment inwhichtextbookwritingisvaluedandencouraged.

IthasbeenapleasuretoworkwithmyeditorialteamatAddisonWesleyLongman,especiallySamiIwata,whoseconfidenceinthisprojecthasalwaysexceeded myown,andJoanMarshandLisaWeber,whoseexpertadvicehasimprovedthe appearanceofeverypage.

Inthespacewheremostauthorsthanktheirimmediatefamilies,Iwouldliketo thankmyfamilyoffriends,especiallyDeb,Jock,John,Lyall,Satoko,andSuzanne. Theirencouragementandpatiencehavebeenunlimited.

1 EnergyinThermalPhysics

1.1ThermalEquilibrium

Themostfamiliarconceptinthermodynamicsis temperature.It’salsooneof thetrickiestconcepts—Iwon’tbereadytotellyouwhattemperature really isuntil Chapter3.Fornow,however,let’sstartwithaverynaivedefinition:

Temperature iswhatyoumeasurewithathermometer. Ifyouwanttomeasurethetemperatureofapotofsoup,youstickathermometer (suchasamercurythermometer)intothesoup,waitawhile,thenlookatthe readingonthethermometer’sscale.Thisdefinitionoftemperatureiswhat’scalled an operationaldefinition,becauseittellsyouhowto measure thequantityin question.

Ok,butwhydoesthisprocedurework?Well,themercuryinthethermometer expandsorcontracts,asitstemperaturegoesupordown.Eventuallythetemperatureofthemercuryequalsthetemperatureofthesoup,andthevolumeoccupied bythemercurytellsuswhatthattemperatureis.

Noticethatourthermometer(andanyotherthermometer)reliesonthefollowingfundamentalfact:Whenyouputtwoobjectsincontactwitheachother,and waitlongenough,theytendtocometothesametemperature.Thispropertyisso fundamentalthatwecaneventakeitasanalternative definition oftemperature:

Temperature isthethingthat’sthesamefortwoobjects,afterthey’ve beenincontactlongenough.

I’llrefertothisasthe theoreticaldefinition oftemperature.Butthisdefinition isextremelyvague:Whatkindof“contact”arewetalkingabouthere?Howlongis “longenough”?Howdoweactuallyascribeanumericalvaluetothetemperature? Andwhatifthereismorethanonequantitythatendsupbeingthesameforboth objects?

Beforeansweringthesequestions,letmeintroducesomemoreterminology: Aftertwoobjectshavebeenincontactlongenough,wesaythattheyarein thermalequilibrium.

Thetimerequiredforasystemtocometothermalequilibriumiscalledthe relaxationtime.

Sowhenyoustickthemercurythermometerintothesoup,youhavetowaitforthe relaxationtimebeforethemercuryandthesoupcometothesametemperature(so yougetagoodreading).Afterthat,themercuryisinthermalequilibriumwith thesoup.

Nowthen,whatdoImeanby“contact”?Agoodenoughdefinitionfornowis that“contact,”inthissense,requiressomemeansforthetwoobjectstoexchange energyspontaneously,intheformthatwecall“heat.”Intimatemechanicalcontact (i.e.,touching)usuallyworksfine,buteveniftheobjectsareseparatedbyempty space,theycan“radiate”energytoeachotherintheformofelectromagneticwaves. Ifyouwantto prevent twoobjectsfromcomingtothermalequilibrium,youneedto putsomekindofthermalinsulationinbetween,likespunfiberglassorthedouble wallofathermosbottle.Andeventhen,they’lleventuallycometoequilibrium; allyou’rereallydoingisincreasingtherelaxationtime.

Theconceptofrelaxationtimeisusuallyclearenoughinparticularexamples. Whenyoupourcoldcreamintohotco⇧ee,therelaxationtimeforthecontentsof thecupisonlyafewseconds.However,therelaxationtimefortheco⇧eetocome tothermalequilibriumwiththesurroundingroomismanyminutes.⇤

Thecream-and-co⇧eeexamplebringsupanotherissue:Herethetwosubstances notonlyendupatthesametemperature,theyalsoendupblendedwitheachother. Theblendingisnotnecessaryfor thermal equilibrium, butconstitutesasecondtype ofequilibrium—di�usiveequilibrium—inwhichthemoleculesofeachsubstance (creammoleculesandco⇧eemolecules,inthiscase)arefreetomovearoundbutno longerhaveanytendencytomoveonewayoranother.Thereisalso mechanical equilibrium,whenlarge-scalemotions(suchastheexpansionofaballoon—see Figure1.1)cantakeplacebutnolongerdo.Foreachtypeofequilibriumbetween twosystems,thereisaquantitythatcanbeexchangedbetweenthesystems:

ExchangedquantityTypeofequilibrium energy thermal volume mechanical particles di⇧usive

NoticethatforthermalequilibriumI’mclaimingthattheexchangedquantityis energy.We’llseesomeevidenceforthisinthefollowingsection. Whentwoobjectsareabletoexchangeenergy,andenergytendstomovespontaneouslyfromonetotheother,wesaythattheobjectthatgivesupenergyisat

⇤ Someauthorsdefinerelaxationtimemorepreciselyasthetimerequiredforthetemperaturedi⌥erencetodecreasebyafactorof e ⇧ 2 7.Inthisbookallwe’llneedisa qualitativedefinition.

Figure1.1. Ahot-airballooninteractsthermally,mechanically,anddi⌥usively withitsenvironment—exchangingenergy,volume,andparticles.Notallofthese interactionsareatequilibrium,however.

a higher temperature,andtheobjectthatsucksinenergyisata lower temperature.Withthisconventioninmind,letmenowrestatethetheoreticaldefinitionof temperature:

Temperature isameasureofthetendencyofanobjecttospontaneously giveupenergytoitssurroundings.Whentwoobjectsareinthermalcontact, theonethattendstospontaneously lose energyisatthe higher temperature.

InChapter3I’llreturntothistheoreticaldefinitionandmakeitmuchmoreprecise, explaining,inthemostfundamentalterms,whattemperaturereally is Meanwhile,Istillneedtomakethe operational definitionoftemperature(what youmeasurewithathermometer)moreprecise.Howdoyoumakeaproperly calibratedthermometer,togetanumerical value fortemperature?

Mostthermometersoperateontheprincipleofthermalexpansion:Materials tendtooccupymorevolume(atagivenpressure)whenthey’rehot.Amercury thermometerisjustaconvenientdeviceformeasuringthevolumeofafixedamount ofmercury.Todefineactual units fortemperature,wepicktwoconvenienttemperatures,suchasthefreezingandboilingpointsofwater,andassignthemarbitrary numbers,suchas0and100.Wethenmarkthesetwopointsonourmercurythermometer,measureo⇧ ahundredequallyspacedintervalsinbetween,anddeclare thatthisthermometernowmeasurestemperatureontheCelsius(orcentigrade) scale,bydefinition!

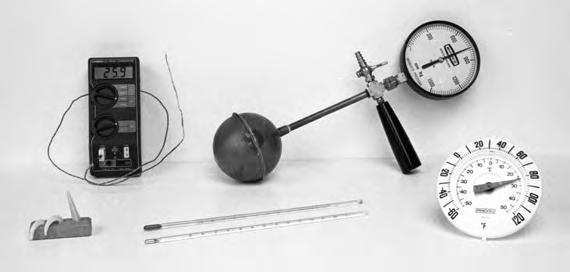

Ofcourseitdoesn’thavetobeamercurythermometer;wecouldinsteadexploit thethermalexpansionofsomeothersubstance,suchasastripofmetal,oragas at fixedpressure.Orwecoulduseanelectricalproperty,suchastheresistance,of somestandardobject.Afewpracticalthermometersforvariouspurposesareshown

Figure1.2. Aselectionofthermometers.Inthecenteraretwoliquid-in-glass thermometers,whichmeasuretheexpansionofmercury(forhighertemperatures) andalcohol(forlowertemperatures).Thedialthermometertotherightmeasures theturningofacoilofmetal,whilethebulbapparatusbehinditmeasuresthe pressureofafixedvolumeofgas.Thedigitalthermometeratleft-rearusesa thermocouple—ajunctionoftwometals—whichgeneratesasmalltemperaturedependentvoltage.Atleft-frontisasetofthreepotter’scones,whichmeltand droopatspecifiedclay-firingtemperatures.

inFigure1.2.It’snotobviousthatthescalesforvariousdi⇧erentthermometers wouldagreeatalltheintermediatetemperaturesbetween0⌅ Cand100⌅ C.Infact, theygenerallywon’t,butinmanycasesthedi⇧erencesarequitesmall.Ifyouever havetomeasuretemperatureswithgreatprecisionyou’llneedtopayattentionto thesedi⇧erences,butforourpresentpurposes,there’snoneedtodesignateanyone thermometerastheo⌃cialstandard.

Athermometerbasedonexpansionofagasisespeciallyinteresting,though, becauseifyouextrapolatethescaledowntoverylowtemperatures,youareledto predictthatforanylow-densitygasatconstantpressure,thevolumeshouldgoto zero atapproximately 273⌅ C.(Inpracticethegaswillalwaysliquefyfirst,but untilthenthetrendisquiteclear.)Alternatively,ifyouholdthevolumeofthegas fixed,thenits pressure willapproachzeroasthetemperatureapproaches 273⌅ C (seeFigure1.3).Thisspecialtemperatureiscalled absolutezero,anddefines thezero-pointofthe absolutetemperaturescale,firstproposedbyWilliam Thomsonin1848.ThomsonwaslaternamedBaronKelvinofLargs,sotheSI unitofabsolutetemperatureisnowcalledthe kelvin. ⇤ Akelvinisthesamesize asadegreeCelsius,butkelvintemperaturesaremeasuredupfromabsolutezero insteadoffromthefreezingpointofwater.Inroundnumbers,roomtemperature isapproximately300K.

Aswe’reabouttosee,manyoftheequationsofthermodynamicsarecorrect only whenyoumeasuretemperatureonthekelvinscale(oranotherabsolutescale suchastheRankinescaledefinedinProblem1.2).Forthisreasonit’susuallywise

⇤ TheUnitPolicehavedecreedthatitisimpermissibletosay“degreekelvin”—the nameissimply“kelvin”—andalsothatthenamesofallO�cialSIUnitsshallnotbe capitalized.

Figure1.3. Datafromastudentexperimentmeasuringthepressureofafixed volumeofgasatvarioustemperatures(usingthebulbapparatusshowninFigure1.2).Thethreedatasetsareforthreedi⌥erentamountsofgas(air)inthebulb. Regardlessoftheamountofgas,thepressureisalinearfunctionoftemperature thatextrapolatestozeroatapproximately 280⌅ C.(Moreprecisemeasurements showthatthezero-pointdoesdependslightlyontheamountofgas,buthasa well-definedlimitof 273 15⌅ Casthedensityofthegasgoestozero.)

toconverttemperaturestokelvinsbeforepluggingthemintoanyformula.(Celsius isok,though,whenyou’retalkingaboutthe di�erence betweentwotemperatures.)

Problem1.1. TheFahrenheittemperaturescaleisdefinedsothaticemeltsat 32⌅ Fandwaterboilsat212⌅ F.

(a) DerivetheformulasforconvertingfromFahrenheittoCelsiusandback.

(b) WhatisabsolutezeroontheFahrenheitscale?

Problem1.2. TheRankinetemperaturescale(abbreviated ⌅ R)usesthesame sizedegreesasFahrenheit,butmeasuredupfromabsolutezerolikekelvin(so RankineistoFahrenheitaskelvinistoCelsius).Findtheconversionformula betweenRankineandFahrenheit,andalsobetweenRankineandkelvin.Whatis roomtemperatureontheRankinescale?

Problem1.3. Determinethekelvintemperatureforeachofthefollowing:

(a) humanbodytemperature;

(b) theboilingpointofwater(atthestandardpressureof1atm);

(c) thecoldestdayyoucanremember;

(d) theboilingpointofliquidnitrogen( 196⌅ C);

(e) themeltingpointoflead(327⌅ C).

Problem1.4. Doesitevermakesensetosaythatoneobjectis“twiceashot”as another?DoesitmatterwhetheroneisreferringtoCelsiusorkelvintemperatures? Explain.

Problem1.5. Whenyou’resickwithafeverandyoutakeyourtemperaturewith athermometer,approximatelywhatistherelaxationtime?

Problem1.6. Giveanexampletoillustratewhyyou cannot accuratelyjudgethe temperatureofanobjectbyhowhotorcolditfeelstothetouch.

Problem1.7. Whenthetemperatureofliquidmercuryincreasesbyonedegree Celsius(oronekelvin),itsvolumeincreasesbyonepartin5500.Thefractional increaseinvolumeperunitchangeintemperature(whenthepressureisheldfixed) iscalledthe thermalexpansioncoe⇥cient, ⇥ : ⇥ ⇤ ⇥V/V ⇥T

(where V isvolume, T istemperature,and ⇥ signifiesachange,whichinthis caseshouldreallybeinfinitesimalif ⇥ istobewelldefined).Soformercury, ⇥ =1/5500K 1 =1 81 ⇥ 10 4 K 1 .(Theexactvaluevarieswithtemperature, butbetween0⌅ Cand200⌅ Cthevariationislessthan1%.)

(a) Getamercurythermometer,estimatethesizeofthebulbatthebottom, andthenestimatewhattheinsidediameterofthetubehastobeinorderfor thethermometertoworkasrequired.Assumethatthethermalexpansion oftheglassisnegligible.

(b) Thethermalexpansioncoe�cientofwatervariessignificantlywithtemperature:Itis7.5 ⇥ 10 4 K 1 at100⌅ C,butdecreasesasthetemperature islowereduntilitbecomes zero at4⌅ C.Below4⌅ Citisslightly negative, reachingavalueof 0 68 ⇥ 10 4 K 1 at0⌅ C.(Thisbehaviorisrelated tothefactthaticeislessdensethanwater.)Withthisbehaviorinmind, imaginetheprocessofalakefreezingover,anddiscussinsomedetailhow thisprocesswouldbedi⌥erentifthethermalexpansioncoe�cientofwater werealwayspositive.

Problem1.8. Forasolid,wealsodefinethe linearthermalexpansioncoefficient, �,asthefractionalincreaseinlengthperdegree:

(a) Forsteel, � is1 1 ⇥ 10 5 K 1 .Estimatethetotalvariationinlengthofa 1-kmsteelbridgebetweenacoldwinternightandahotsummerday.

(b) ThedialthermometerinFigure1.2usesacoiledmetalstripmadeoftwo di⌥erentmetalslaminatedtogether.Explainhowthisworks.

(c) Provethatthevolumethermalexpansioncoe�cientofasolidisequalto thesumofitslinearexpansioncoe�cientsinthethreedirections: ⇥ = �x + �y + �z .(Soforanisotropicsolid,whichexpandsthesameinall directions, ⇥ =3�.)

1.2TheIdealGas

Manyofthepropertiesofalow-densitygascanbesummarizedinthefamous ideal gaslaw, PV = nRT, (1.1) where P =pressure, V =volume, n =numberofmolesofgas, R isauniversal constant,and T isthetemperature inkelvins.(IfyouweretoplugaCelsius temperatureintothisequationyouwouldgetnonsense—itwouldsaythatthe

volumeorpressureofagasgoestozeroatthefreezingtemperatureofwaterand becomesnegativeatstilllowertemperatures.)

Theconstant R intheidealgaslawhastheempiricalvalue

R =8 31 J mol K

inSIunits,thatis,whenyoumeasurepressureinN/m2 =Pa(pascals)andvolume inm3 .Chemistsoftenmeasurepressureinatmospheres(1atm=1 013 ⇥ 105 Pa) orbars(1bar=105 Paexactly)andvolumeinliters(1liter=(0.1m)3 ),sobe careful.

A mole ofmoleculesisAvogadro’snumberofthem,

A =6 02 ⇥ 1023

Thisisanother“unit”that’smoreusefulinchemistrythaninphysics.Moreoften wewillwanttosimplydiscussthenumberof molecules,denotedbycapital N :

Ifyouplugin N/NA for n intheidealgaslaw,thengrouptogetherthecombination R/NA andcallitanewconstant k ,youget PV = NkT. (1.5)

Thisistheformoftheidealgaslawthatwe’llusuallyuse.Theconstant k iscalled Boltzmann’sconstant,andistinywhenexpressedinSIunits(sinceAvogadro’s numberissohuge):

Inordertorememberhowalltheconstantsarerelated,Irecommendmemorizing

Unitsaside,though,theidealgaslawsummarizesanumberofimportantphysicalfacts.Foragivenamountofgasatagiventemperature,doublingthepressure squeezesthegasintoexactlyhalfasmuchspace.Or,atagivenvolume,doubling thetemperaturecausesthepressuretodouble.Andsoon.Theproblemsbelow explorejustafewoftheimplicationsoftheidealgaslaw.

Likenearlyallthelawsofphysics,theidealgaslawisan approximation,never exactlytrueforarealgasintherealworld.Itisvalidinthelimitoflowdensity, whentheaveragespacebetweengasmoleculesismuchlargerthanthesizeofa molecule.Forair(andothercommongases)atroomtemperatureandatmospheric pressure,theaveragedistancebetweenmoleculesisroughlytentimesthesizeofa molecule,sotheidealgaslawisaccurateenoughformostpurposes.

Problem1.9. Whatisthevolumeofonemoleofair,atroomtemperatureand 1atmpressure?

Problem1.10. Estimatethenumberofairmoleculesinanaverage-sizedroom.

Problem1.11. Rooms A and B arethesamesize,andareconnectedbyanopen door.Room A,however,iswarmer(perhapsbecauseitswindowsfacethesun). Whichroomcontainsthegreatermassofair?Explaincarefully.

Problem1.12. Calculatetheaveragevolumepermoleculeforanidealgasat roomtemperatureandatmosphericpressure.Thentakethecuberoottoget anestimateoftheaveragedistancebetweenmolecules.Howdoesthisdistance comparetothesizeofasmallmoleculelikeN2 orH2 O?

Problem1.13. Amoleisapproximatelythenumberofprotonsinagramof protons.Themassofaneutronisaboutthesameasthemassofaproton,while themassofanelectronisusuallynegligibleincomparison,soifyouknowthe totalnumberofprotonsandneutronsinamolecule(i.e.,its“atomicmass”),you knowtheapproximatemass(ingrams)ofamoleofthesemolecules.⇤ Referringto theperiodictableatthebackofthisbook,findthemassofamoleofeachofthe following:water,nitrogen(N2 ),lead,quartz(SiO2 ).

Problem1.14. Calculatethemassofamoleofdryair,whichisamixtureofN2 (78%byvolume),O2 (21%),andargon(1%).

Problem1.15. Estimatetheaveragetemperatureoftheairinsideahot-air balloon(seeFigure1.1).Assumethatthetotalmassoftheunfilledballoonand payloadis500kg.Whatisthemassoftheairinsidetheballoon?

Problem1.16. Theexponentialatmosphere.

(a) Considerahorizontalslabofairwhosethickness(height)is dz .Ifthisslab isatrest,thepressureholdingitupfrombelowmustbalanceboththe pressurefrom aboveandtheweightoftheslab.Usethisfacttofindan expressionfor dP/dz ,thevariationofpressurewithaltitude,intermsof thedensityofair.

(b) Usetheidealgaslawtowritethedensityofairintermsofpressure,temperature,andtheaveragemass m oftheairmolecules.(Theinformation neededtocalculate m isgiveninProblem1.14.)Show,then,thatthe pressureobeysthedi⌥erentialequation

dP

dz = mg kT P, calledthe barometricequation

(c) Assumingthatthetemperatureoftheatmosphereisindependentofheight (notagreatassumptionbutnotterribleeither),solvethebarometricequationtoobtainthepressureasafunctionofheight: P (z )= P (0)e mgz/kT . Showalsothatthedensityobeysasimilarequation.

⇤ Theprecisedefinitionofamoleisthenumberofcarbon-12atomsin12gramsof carbon-12.The atomicmass ofasubstanceisthenthemass,ingrams,ofexactlyone moleofthatsubstance.Massesof individual atomsandmoleculesareoftengivenin atomicmassunits,abbreviated“u”,where1uisdefinedasexactly1/12themassof acarbon-12atom.Themassofanisolatedprotonisactuallyslightlygreaterthan1u, whilethemassofanisolatedneutronisslightlygreaterstill.Butinthisproblem,asin mostthermalphysicscalculations,it’sfinetoroundatomicmassestothenearestinteger, whichamountstocountingthetotalnumberofprotonsandneutrons.

(d) Estimatethepressure,inatmospheres,atthefollowinglocations:Ogden, Utah(4700ftor1430mabovesealevel);Leadville,Colorado(10,150ft, 3090m);Mt.Whitney,California(14,500ft,4420m);Mt.Everest,Nepal/ Tibet(29,000ft,8850m).(Assumethatthepressureatsealevelis1atm.)

Problem1.17. Evenatlowdensity,realgasesdon’tquiteobeytheidealgas law.Asystematicwaytoaccountfordeviationsfromidealbehavioristhe virial expansion, PV = nRT �1+ B (T ) (V/n) + C (T ) (V/n)2 + , wherethefunctions B (T ), C (T ),andsoonarecalledthe virialcoe⇥cients Whenthedensityofthegasisfairlylow,sothatthevolumepermoleislarge, eachtermintheseriesismuchsmallerthantheonebefore.Inmanysituationsit’s su�cienttoomitthethirdtermandconcentrateonthesecond,whosecoe�cient B (T )iscalledthesecondvirialcoe�cient(thefirstcoe�cientbeing1).Hereare somemeasuredvaluesofthesecondvirialcoe�cientfornitrogen(N2 ):

(a) Foreachtemperatureinthetable,computethesecondterminthevirial equation, B (T )/(V/n),fornitrogenatatmosphericpressure.Discussthe validityoftheidealgaslawundertheseconditions.

(b) Thinkabouttheforcesbetweenmolecules,andexplainwhywemightexpect B (T )tobenegativeatlowtemperaturesbutpositiveathightemperatures.

(c) Anyproposedrelationbetween P , V ,and T ,liketheidealgaslaworthe virialequation,iscalledan equationofstate.Anotherfamousequation ofstate,whichisqualitativelyaccurateevenfordensefluids,isthe van derWaalsequation, ⌃P + an 2 V

⌥(V nb)= nRT, where a and b areconstantsthatdependonthetypeofgas.Calculatethe secondandthirdvirialcoe�cients(B and C )foragasobeyingthevander Waalsequation,intermsof a and b.(Hint:Thebinomialexpansionsays that(1+ x)p ⇧ 1+ px + 1 2 p(p 1)x 2 ,providedthat |px| ⌃ 1.Applythis approximationtothequantity[1 (nb/V )] 1 .)

(d) PlotagraphofthevanderWaalspredictionfor B (T ),choosing a and b soastoapproximatelymatchthedatagivenabovefornitrogen.Discuss theaccuracyofthevanderWaalsequationoverthisrangeofconditions. (ThevanderWaalsequationisdiscussedmuchfurtherinSection5.3.)

MicroscopicModelofanIdealGas

InSection1.1Idefinedtheconceptsof“temperature”and“thermalequilibrium,” andbrieflynotedthatthermalequilibriumarisesthroughtheexchangeof energy betweentwosystems.Buthow,exactly,istemperaturerelatedtoenergy?The answertothisquestionisnotsimpleingeneral,butit is simpleforanidealgas, asI’llnowattempttodemonstrate.

I’mgoingtoconstructamental“model”ofacontainerfullofgas.⇤ Themodel willnotbeaccurateinallrespects,butIhopetopreservesomeofthemostimportantaspectsofthebehaviorofreallow-densitygases.Tostartwith,I’llmakethe modelassimpleaspossible:Imagineacylindercontainingjust one gasmolecule, asshowninFigure1.4.Thelengthofthecylinderis L,theareaofthepistonis A,andthereforethevolumeinsideis V = LA.Atthemoment,themoleculehas avelocityvector ⌘ v ,withhorizontalcomponent vx .Astimepasses,themolecule bounceso⇧ thewallsofthecylinder,soitsvelocitychanges.I’llassume,however, thatthesecollisionsarealwayselastic,sothemoleculedoesn’tloseanykineticenergy;its speed neverchanges.I’llalsoassumethatthesurfacesofthecylinderand pistonareperfectlysmooth,sothemolecule’spathasitbouncesissymmetrical aboutalinenormaltothesurface,justlikelightbouncingo⇧ amirror.†

Here’smyplan.Iwanttoknowhowthe temperature ofagasisrelatedto thekinetic energy ofthemoleculesitcontains.ButtheonlythingIknowabout temperaturesofaristheidealgaslaw,

PV = NkT (1.8) (where P ispressure).SowhatI’ll firsttrytodoisfigureouthowthe pressure is relatedtothekineticenergy;thenI’llinvoketheidealgaslawtorelatepressureto temperature.

Well,whatisthepressureofmysimplifiedgas?Pressuremeansforceperunit area,exertedinthiscaseonthepiston(andtheotherwallsofthecylinder).What

Pistonarea= A

Volume= V = LA

Figure1.4. Agreatlysimplifiedmodelofanidealgas, withjustonemoleculebouncingaroundelastically.

Length= L

⇤ Thismodeldatesbacktoa1738treatisebyDanielBernoulli,althoughmanyofits implicationswerenotworkedoutuntilthe1840s.

† Theseassumptionsareactuallyvalidonlyforthe average behaviorofmoleculesbouncingo⌥ surfaces;inany particular collisionamoleculemightgainorloseenergy,andcan leavethesurfaceatalmostanyangle.

isthepressureexertedonthepistonbythemolecule?Usuallyit’szero,sincethe moleculeisn’teventouchingthepiston.Butperiodicallythemoleculecrashesinto thepistonandbounceso⇧,exertingarelativelylargeforceonthepistonforabrief moment.WhatIreallywanttoknowisthe average pressureexertedonthepiston overlongtimeperiods.I’lluseanoverbartodenoteanaveragetakenoversome longtimeperiod,likethis: P .Icancalculatetheaveragepressureasfollows:

InthefirststepI’vewrittenthepressureintermsofthe x componentoftheforce exertedbythemoleculeonthepiston.InthesecondstepI’veusedNewton’sthird lawtowritethisintermsoftheforceexertedbythepistononthemolecule.Finally, inthethirdstep,I’veusedNewton’ssecondlawtoreplacethisforcebythemass m ofthemoleculetimesitsacceleration, ⇥vx /⇥t.I’mstillsupposedtoaverageover somelongtimeperiod;Icandothissimplybytaking ⇥t tobefairlylarge.However, Ishouldincludeonlythoseaccelerationsthatarecausedbythepiston,notthose causedbythewallontheoppositeside.Thebestwaytoaccomplishthisistotake ⇥t tobeexactlythetimeittakesforthemoleculetoundergooneround-tripfrom thelefttotherightandbackagain:

(Collisionswiththeperpendicularwallswillnota⇧ectthemolecule’smotioninthe x direction.)Duringthistimeinterval,themoleculeundergoesexactlyonecollision withthepiston,andthechangeinits x velocityis

Puttingtheseexpressionsintoequation1.9,Ifindfortheaveragepressureonthe piston

It’sinterestingtothinkaboutwhythereare two factorsof vx inthisequation.One ofthemcamefrom ⇥vx :Ifthemoleculeismovingfaster,eachcollisionismore violentandexertsmorepressure.Theotheronecamefrom ⇥t:Ifthemoleculeis movingfaster,collisionsoccurmorefrequently.

Nowimaginethatthecylindercontainsnotjustonemolecule,butsomelarge number, N ,ofidenticalmolecules,withrandom⇤ positionsanddirectionsofmotion. I’llpretendthatthemoleculesdon’tcollideorinteractwitheachother—justwith

⇤ What,exactly,doestheword random mean?Philosophershavefilledthousandsof pageswithattemptstoanswerthisquestion.Fortunately,wewon’tbeneedingmuchmore thananeverydayunderstandingoftheword.HereIsimplymeanthatthedistribution ofmolecularpositionsandvelocityvectorsismoreorlessuniform;there’snoobvious tendencytowardanyparticulardirection.

thewalls.Sinceeachmoleculeperiodicallycollideswiththepiston,theaverage pressureisnowgivenbyasumoftermsoftheformofequation1.12:

Ifthenumberofmoleculesislarge,thecollisionswillbesofrequentthatthepressure isessentiallycontinuous,andwecanforgettheoverbaronthe P .Ontheother hand,thesumof v 2 x forall N moleculesisjust N timesthe average oftheir v 2 x values.Usingthesameoverbartodenotethisaverageoverallmolecules,equation 1.13thenbecomes

SofarI’vejustbeenexploringtheconsequencesofmymodel,withoutbringing inanyfactsabouttherealworld(otherthanNewton’slaws).Butnowletme invoketheidealgaslaw(1.8),treatingitasanexperimentalfact.Thisallowsme tosubstitute NkT for PV ontheleft-handsideofequation1.14.Cancelingthe N ’s,we’releftwith

Iwrotethisequationthesecondwaybecausetheleft-handsideisalmostequalto theaveragetranslational kineticenergy ofthemolecules.Theonlyproblemis the x subscript,whichwecangetridofbyrealizingthatthesameequationmust alsoholdfor y and z :

Theaveragetranslationalkineticenergyisthen

(Notethattheaverageofasumisthesumoftheaverages.)

Thisisagoodplacetopauseandthinkaboutwhatjusthappened.Istarted withanaivemodelofagasasabunchofmoleculesbouncingaroundinsidea cylinder.Ialsoinvokedtheidealgaslawasanexperimentalfact.Conclusion:The averagetranslationalkineticenergyofthemoleculesinagasisgivenbyasimple constanttimesthetemperature.Soifthismodelisaccurate,thetemperatureofa gasisadirectmeasureoftheaveragetranslationalkineticenergyofitsmolecules.

ThisresultgivesusaniceinterpretationofBoltzmann’sconstant, k .Recallthat k hasjusttherightunits,J/K,toconvertatemperatureintoanenergy.Indeed,we nowseethat k isessentiallya conversionfactor betweentemperatureandmolecular energy,atleastforthissimplesystem.Thinkaboutthenumbers,though:Foran airmoleculeatroomtemperature(300K),thequantity kT is

(1 38 ⇥ 10 23 J/K)(300K)=4 14 ⇥ 10 21 J, (1.18)

andtheaveragetranslationalenergyis3/2timesasmuch.Ofcourse,sincemoleculesaresosmall,wewouldexpecttheirkineticenergiestobetiny.Thejoule, though,isnotaveryconvenientunitfordealingwithsuchsmallenergies.Instead

weoftenusethe electron-volt (eV),whichisthekineticenergyofanelectronthat hasbeenacceleratedthroughavoltagedi⇧erenceofonevolt:1eV=1 6 ⇥ 10 19 J. Boltzmann’sconstantis8 62 ⇥ 10 5 eV/K,soatroomtemperature,

Eveninelectron-volts,molecularenergiesatroomtemperaturearerathersmall. Ifyouwanttoknowtheaverage speed ofthemoleculesinagas,youcan almost getitfromequation1.17,butnotquite.Solvingfor v 2 gives

butifyoutakethesquarerootofbothsides,yougetnottheaveragespeed,but ratherthesquarerootoftheaverageofthesquaresofthespeeds(root-mean-square, orrmsforshort):

We’llseeinSection6.4that vrms isonlyslightlylargerthan v ,soifyou’renottoo concernedaboutaccuracy, vrms isafineestimateoftheaveragespeed.According toequation1.21,lightmoleculestendtomovefasterthanheavyones,atagiven temperature.Ifyoupluginsomenumbers,you’llfindthatsmallmoleculesat ordinarytemperaturesarebouncingaroundat hundreds ofmeterspersecond.

Gettingbacktoourmainresult,equation1.17,youmaybewonderingwhether it’sreallytrueforrealgases,givenallthesimplifyingassumptionsImadeinderiving it.Strictlyspeaking,myderivationbreaksdownifmoleculesexertforcesoneach other,orifcollisionswiththewallsareinelastic,oriftheidealgaslawitselffails. Briefinteractionsbetweenmoleculesaregenerallynobigdeal,sincesuchcollisions won’tchangetheaveragevelocitiesofthemolecules.Theonlyseriousproblemis whenthegasbecomessodensethatthespaceoccupiedbythemoleculesthemselves becomesasubstantialfractionofthetotalvolumeofthecontainer.Thenthebasic pictureofmoleculesflyinginstraightlinesthroughemptyspacenolongerapplies. Inthiscase,however,theidealgaslawalsobreaksdown,insuchawayasto preciselypreserveequation1.17.Consequently,thisequationisstilltrue,notonly fordensegasesbutalsoformostliquidsandsometimesevensolids!I’llproveitin Section6.3.

Problem1.18. Calculatethermsspeedofanitrogenmoleculeatroomtemperature.

Problem1.19. Supposeyouhaveagascontaininghydrogenmoleculesandoxygen molecules,inthermalequilibrium.Whichmoleculesaremovingfaster,onaverage? Bywhatfactor?

Problem1.20. Uraniumhastwocommonisotopes,withatomicmassesof238 and235.Onewaytoseparatetheseisotopesistocombinetheuraniumwith fluorinetomakeuraniumhexafluoridegas,UF6 ,thenexploitthedi⌥erenceinthe averagethermalspeedsofmoleculescontainingthedi⌥erentisotopes.Calculate thermsspeedofeachtypeofmoleculeatroomtemperature,andcomparethem.

Problem1.21. Duringahailstorm,hailstoneswithanaveragemassof2gand aspeedof15m/sstrikeawindowpaneata45⌅ angle.Theareaofthewindow is0.5m2 andthehailstoneshititatarateof30persecond.Whataverage pressuredotheyexertonthewindow?Howdoesthiscomparetothepressureof theatmosphere?

Problem1.22. Ifyoupokeaholeinacontainerfullofgas,thegaswillstart leakingout.Inthisproblemyouwillmakearoughestimateoftherateatwhich gasescapesthroughahole.(Thisprocessiscalled e�usion,atleastwhenthe holeissu�cientlysmall.)

(a) Considerasmallportion(area= A)oftheinsidewallofacontainerfull ofgas.Showthatthenumberofmoleculescollidingwiththissurfacein atimeinterval ⇥t is PA ⇥t/(2mvx ),where P isthepressure, m isthe averagemolecularmass,and vx istheaverage x velocityofthosemolecules thatcollidewiththewall.

(b) It’snoteasytocalculate vx ,butagoodenoughapproximationis(v 2 x )1/2 , wherethebarnowrepresentsanaverageoverallmoleculesinthegas.Show that(v 2 x )1/2 = �kT/m.

(c) Ifwenowtakeawaythissmallpartofthewallofthecontainer,themoleculesthat would havecollidedwithitwillinsteadescapethroughthehole. Assumingthatnothing enters throughthehole,showthatthenumber N ofmoleculesinsidethecontainerasafunctionoftimeisgovernedbythe di⌥erentialequation

Solvethisequation(assumingconstanttemperature)toobtainaformula oftheform N (t)= N (0)e t/� ,where ✏ isthe“characteristictime”for N (and P )todropbyafactorof e

(d) Calculatethecharacteristictimeforairatroomtemperaturetoescape froma1-litercontainerpuncturedbya1-mm2 hole.

(e) Yourbicycletirehasaslowleak,sothatitgoesflatwithinaboutanhour afterbeinginflated.Roughlyhowbigisthehole?(Useanyreasonable estimateforthevolumeofthetire.)

(f) InJulesVerne’s RoundtheMoon,thespacetravelersdisposeofadog’s corpsebyquicklyopeningawindow,tossingitout,andclosingthewindow.Doyouthinktheycandothisquicklyenoughtopreventasignificant amountofairfromescaping?Justifyyouranswerwithsomeroughestimatesandcalculations.

1.3EquipartitionofEnergy

Equation1.17isaspecialcaseofamuchmoregeneralresult,calledthe equipartitiontheorem.Thistheoremconcernsnotjusttranslationalkineticenergybut all formsofenergyforwhichtheformulaisaquadraticfunctionofacoordinateor velocitycomponent.Eachsuchformofenergyiscalleda degreeoffreedom.So far,theonlydegreesoffreedomI’vetalkedaboutaretranslationalmotioninthe x, y ,and z directions.Otherdegreesoffreedommightincluderotationalmotion, vibrationalmotion,andelasticpotentialenergy(asstoredinaspring).Lookat

thesimilaritiesoftheformulasforallthesetypesofenergy:

Thefourthandfifthexpressionsareforrotationalkineticenergy,afunctionof themomentofinertia I andtheangularvelocity � .Thesixthexpressionisfor elasticpotentialenergy,afunctionofthespringconstant ks andtheamountof displacementfromequilibrium, x.Theequipartitiontheoremsimplysaysthatfor eachdegreeoffreedom,theaverageenergywillbe 1 2 kT :

Equipartitiontheorem: Attemperature T ,theaverageenergyofany quadraticdegreeoffreedomis 1 2 kT .

Ifasystemcontains N molecules,eachwith f degreesoffreedom,andthereare noother(non-quadratic)temperature-dependentformsofenergy,thenits total thermalenergy is

Technicallythisisjustthe average totalthermalenergy,butif N islarge,fluctuationsawayfromtheaveragewillbenegligible.

I’llprovetheequipartitiontheoreminSection6.3.Fornow,though,it’simportanttounderstandexactlywhatitsays.Firstofall,thequantity Uthermal is almostneverthe total energyofasystem;there’salso“static”energythatdoesn’t changeasyouchangethetemperature,suchasenergystoredinchemicalbondsor therestenergies(mc2 )ofalltheparticlesinthesystem.Soit’ssafesttoapplythe equipartitiontheoremonlyto changes inenergywhenthetemperatureisraisedor lowered,andtoavoidphasetransformationsandotherreactionsinwhichbonds betweenparticlesmaybebroken.

Anotherdi⌃cultywiththeequipartitiontheoremisincountinghowmanydegreesoffreedomasystemhas.Thisisaskillbestlearnedthroughexamples.Ina gasofmonatomicmoleculeslikeheliumorargon,onlytranslationalmotioncounts, soeachmoleculehasthreedegreesoffreedom,thatis, f =3.Inadiatomicgas likeoxygen(O2 )ornitrogen(N2 ),eachmoleculecanalso rotate abouttwodi⇧erentaxes(seeFigure1.5).Rotationabouttheaxisrunningdownthelengthofthe moleculedoesn’tcount,forreasonshavingtodowithquantummechanics.The

Figure1.5. Adiatomicmoleculecanrotateabouttwoindependentaxes,perpendiculartoeachother.Rotationaboutthethirdaxis,downthelengthofthe molecule,isnotallowed.

sameistrueforcarbondioxide(CO2 ),sinceitalsohasanaxisofsymmetrydown itslength.However,mostpolyatomicmoleculescanrotateaboutallthreeaxes.

It’snotobviouswhyarotationaldegreeoffreedomshouldhaveexactlythesame averageenergyasatranslationaldegreeoffreedom.However,ifyouimaginegas moleculesknockingaroundinsideacontainer,collidingwitheachotherandwiththe walls,youcanseehowtheaveragerotationalenergyshouldeventuallyreachsome equilibriumvaluethatislargerifthemoleculesaremovingfast(hightemperature) andsmallerifthemoleculesaremovingslow(lowtemperature).Inanyparticular collision,rotationalenergymightbeconvertedtotranslationalenergyorviceversa, butonaveragetheseprocessesshouldbalanceout.

Adiatomicmoleculecanalso vibrate,asifthetwoatomswereheldtogetherby aspring.Thisvibrationshouldcountas two degreesoffreedom,oneforthevibrationalkineticenergyandoneforthepotentialenergy.(Youmayrecallfromclassical mechanicsthattheaveragekineticandpotentialenergiesofasimpleharmonicoscillatorareequal—aresultthatisconsistentwiththeequipartitiontheorem.)More complicatedmoleculescanvibrateinavarietyofways:stretching,flexing,twisting. Each“mode”ofvibrationcountsastwodegreesoffreedom.

However,atroomtemperaturemanyvibrationaldegreesoffreedomdo not contributetoamolecule’sthermalenergy.Again,theexplanationliesinquantummechanics,aswewillseeinChapter3.Soairmolecules(N2 andO2 ),for instance,haveonlyfivedegreesoffreedom,notseven,atroomtemperature.At highertemperatures,thevibrationalmodes do eventuallycontribute.Wesaythat thesemodesare“frozenout” atroomtemperature;evidently,collisionswithother moleculesaresu⌃cientlyviolenttomakeanairmoleculerotate,buthardlyever violentenoughtomakeitvibrate.

Inasolid,eachatomcanvibrateinthreeperpendiculardirections,soforeach atomtherearesixdegreesoffreedom(threeforkineticenergyandthreeforpotentialenergy).AsimplemodelofacrystallinesolidisshowninFigure1.6.Ifwelet N standforthenumberof atoms and f standforthenumberofdegreesoffreedom peratom,thenwecanuseequation1.23with f =6forasolid.Again,however, someofthedegreesoffreedommaybe“frozenout”atroomtemperature.

Liquidsaremorecomplicatedthaneithergasesorsolids.Youcangenerallyuse theformula 3 2 kT tofindtheaveragetranslationalkineticenergyofmoleculesina Figure1.6. The“bed-spring”model ofacrystallinesolid.Eachatomis likeaball,joinedtoitsneighborsby springs.Inthreedimensions,thereare sixdegreesoffreedomperatom:three fromkineticenergyandthreefrompotentialenergystoredinthesprings.

liquid,buttheequipartitiontheoremdoesn’tworkfortherestofthethermalenergy, becausetheintermolecularpotentialenergiesarenotnicequadraticfunctions.

Youmightbewonderingwhatpracticalconsequencestheequipartitiontheorem has:Howcanwe test it,experimentally?Inbrief,wewouldhavetoaddsomeenergy toasystem,measurehowmuchitstemperaturechanges,andcomparetoequation 1.23.I’lldiscussthisprocedureinmoredetail,andshowsomeexperimentalresults, inSection1.6.

Problem1.23. Calculatethetotalthermalenergyinaliterofheliumatroom temperatureandatmosphericpressure.Thenrepeatthecalculationforaliterof air.

Problem1.24. Calculatethetotalthermalenergyinagramofleadatroom temperature,assumingthatnoneofthedegreesoffreedomare“frozenout”(this happenstobeagoodassumptioninthiscase).

Problem1.25. Listallthedegreesoffreedom,orasmanyasyoucan,fora moleculeofwatervapor.(Thinkcarefullyaboutthevariouswaysinwhichthe moleculecanvibrate.)

1.4HeatandWork

Muchofthermodynamicsdealswiththreecloselyrelatedconcepts: temperature, energy,and heat.Muchofstudents’di⌃cultywiththermodynamicscomesfrom confusingthesethreeconceptswitheachother.Letmeremindyouthattemperature,fundamentally,isameasureofanobject’stendencytospontaneouslygiveup energy.Wehavejustseenthatinmanycases,whentheenergycontentofasystem increases,sodoesitstemperature.Butpleasedon’tthinkofthisasthe definition of temperature—it’smerelyastatement about temperaturethathappenstobetrue.

Tofurtherclarifymatters,Ireallyshouldgiveyouaprecisedefinitionof energy.Unfortunately,Ican’tdothis.Energyisthemostfundamentaldynamical conceptinallofphysics,andforthisreason, Ican’ttellyouwhatitisinterms ofsomethingmorefundamental.Ican,however,listthevarious forms ofenergy— kinetic,electrostatic,gravitational,chemical,nuclear—andaddthestatementthat, whileenergycanoftenbeconvertedfromoneformtoanother,the total amount ofenergyintheuniverseneverchanges.Thisisthefamouslawof conservation ofenergy.Isometimespictureenergyasaperfectlyindestructible(andunmakable)fluid,whichmovesaboutfromplacetoplacebutwhosetotalamountnever changes.(Thisimageisconvenientbut wrong —theresimplyisn’tanysuchfluid.)

Suppose,forinstance,thatyouhaveacontainerfullofgasorsomeotherthermodynamicsystem.Ifyounoticethattheenergyofthesystemincreases,youcan concludethatsomeenergycameinfromoutside;itcan’thavebeenmanufactured onthespot,sincethiswouldviolatethelawofconservationofenergy.Similarly, iftheenergyofyoursystemdecreases,thensomeenergymusthaveescapedand goneelsewhere.Thereareallsortsofmechanismsbywhichenergycanbeputinto ortakenoutofasystem.However,inthermodynamics,weusuallyclassifythese mechanismsundertwocategories: heat and work.