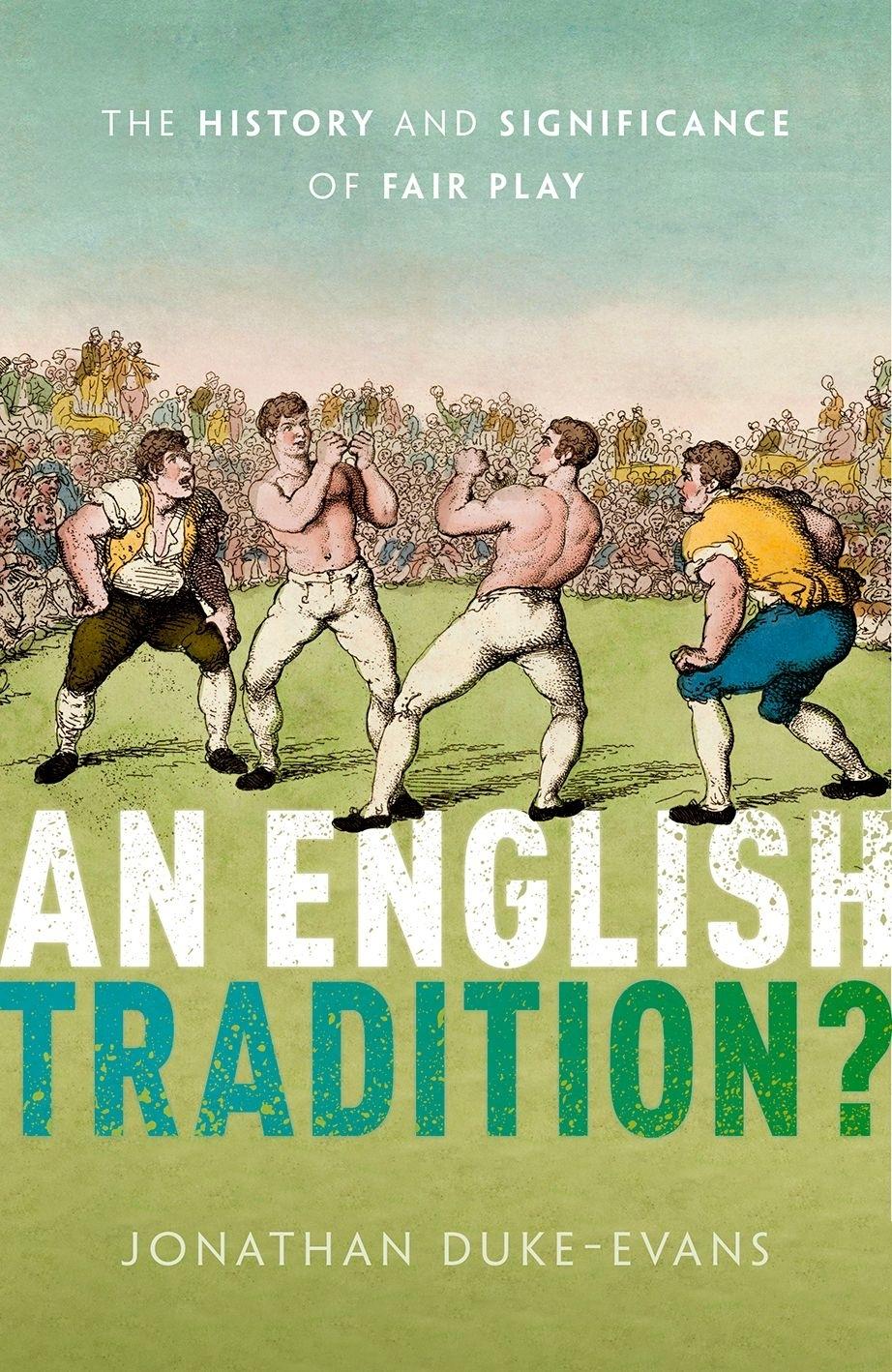

AN ENGLISH TRADITION?

THE HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE OF FAIR PLAY

JONATHAN DUKE-EVANS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Jonathan Duke-Evans 2023

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2023

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022936515

ISBN 978–0–19–285999–0

ebook ISBN 978–0–19–267629–0

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192859990.001.0001

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Preface

I can no longer remember precisely when I decided to write about the history of fair play. I was noting down scraps of information that seemed relevant for at least a dozen years before I started work in earnest. A casual conversation with a friend in which we asked ourselves why both cricket and football sides have eleven members and not ten or twelve had something to do with it.1 When the debate about British values, and how far new citizens are expected to buy into them, began to attract a lot of attention under the Blair administration, fair play featured prominently in the argument, and it seemed to me then that the task of analysing the concept and enquiring whether it was indeed specifically British would be a worthwhile one.

An American acquaintance who asked me about my research claimed that she had never heard of any British reputation for fair play, and wanted to know how it was to be squared with slavery and the Empire. She had put her finger on one of the most difficult questions which have arisen in this study, and one which seems highly relevant to the effort which so many historians are making today to throw light on Britain’s imperial reckoning. In the course of researching the book I have developed some partial answers to such questions, hypotheses which suggest how ideas about fairness can flourish and yet be sharply limited in their application to different kinds of people: noble and common, male and female, white and black; but also how those limitations began to be cast off in our progress towards a more inclusive ideal of fair play.

I have tried to write a book which could be enjoyed by anyone interested in history, but one that aspires to high standards of

evidence and documentation. I hope those readers who have spent a lifetime studying the subject will be tolerant of any explanations and clarifications which they may consider unnecessary. My own career began with a doctoral thesis on political writing in early 18thcentury England which was accepted back in 1980. I take this opportunity to thank, belatedly and posthumously, my supervisor, Garry Bennett, who ended his own life a few years later when an article which he had published anonymously about politics in the contemporary Church of England was seized on by the media, treated as a national scandal for a few days, and then forgotten. I had moved on to work for the government, and much of the work I did hinged on questions of what was fair and unfair in matters of criminal justice and military operations. Some of that experience may have influenced the composition of this book. A few years into my Civil Service career I was awarded a Harkness Fellowship, and used it to study public administration for a year at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. I learned a great deal about the way in which welfare economics can clarify questions of fairness, and though that is not the primary focus of this book I will always be grateful to the late Professor Mark Kleiman for opening up these new ways of seeing the world. Going further back, I would like to acknowledge here everyone who fostered my fascination with the realms of history and literature, and to recall with particular gratitude the teaching of Mike Booker, Roger Perry, Jim Hunter, Phil Revill, and Stan Houston. I owe much, too, to my father, David Duke-Evans, whose intellectual curiosity and love of learning are as strong as ever as he approaches his tenth decade. Many friends have helped me with the book. Among those at Oxford University Gervase Rosser has read the whole text and provided comments full of insight and Ross McKibbin steered me towards some of the contemporary theorists of games, while Henry Woudhuysen has given me valuable pointers on Elizabethan literature and Karen O’Brien on the earliest English feminist writers. Elsewhere, David Cooke has alerted me to many of the resonances of the idea of play, while my sports-loving friends Roger Titford, Paul

Silver, John and Elaine Warne, Paul Bolt, and Kate Cooke have all enhanced chapter 10 with their knowledge. Kim Silver made many useful suggestions about what I had to say on English law, as did Nick Bruce on military history, while Bill Grundy commented on my thoughts on Judaic and Christian ethics. Francis Wilkinson has been a regular source of ideas and questions. Much-appreciated formatting help has been provided by Delia Caple.

Dick Holt of Leicester De Montfort University is another who has read the whole text, which has benefited greatly both from his own published work and his comments on my ideas. His colleague Dilwyn Porter cleared up a point on the Corinthians that was puzzling me, while Mark Foster of the Sussex Cricket Museum was very kind in helping me with a query on the local hero C B Fry. Ben Sanders of the Ministry of Defence guided me to relevant parts of the Geneva Conventions. Matthew Cotton of the Oxford University Press took an immediate interest in an unsolicited submission from an unknown author, and he and Cathryn Steele have expertly guided the book through to publication, a process which has been facilitated by the expertise of Saraswathi Cesar Rajan, Edwin Pritchard, and Hayley Buckley.

Most of all, Sir Keith Thomas, whose classes were an inspiration to me and so many other students, has taken a generous and lively interest in this project. Our meetings in Oxford and on Zoom to discuss the work in progress were every bit as challenging as those tutorial sessions so many years ago. His strong recommendation that the study should be firmly grounded in an understanding of the way in which people wrote and talked about fair play has been fundamental to the plan of the book. I dedicate it jointly to him, to my mother Denise Watson who died just as it was being finished, and to my wife Patricia, whose love and encouragement have been unfailing.

Several books have been entitled “fair play”, but this is I think the first study that tries to offer a comprehensive history of the phrase and the assumptions that underlie it. In writing it I have found insights new to me about some fundamental aspects of British life,

such as social class, law, leisure, and the existence or otherwise of a unifying culture. I hope that readers will share some of the enjoyment, and surprise, that I have experienced in the course of my work.

ListofIllustrations

Introduction: The problem of fair play

What do we mean when we talk about fair play?

Fair play—the history of a phrase

Classical perspectives

Christianity and chivalry

Fair play in pre-industrial Britain: Law, politics, religion, and class

Fair play—the popular strand

The rise of the gentleman

The realm beyond England

The great appropriation

The expanding circle

The wider world

Fair play in the 20th century and beyond

Conclusion: Fair play and the British

Appendix1:Quantifyingtheuseof“fairplay”

Appendix2:Fairplayquotientsforteamsplayingfifteenormore matchesatWorldCupfinals,1930to2018

Endnotes

Bibliography

Index

1 Introduction

The problem of fair play

For the past three hundred years many people in what is now the United Kingdom have claimed a love of fair play as one of their most deep-seated qualities. They have been inconsistent about what fair play means, and about whether they mean England or Britain when they identify it as a national characteristic. But it comes up perhaps more than any other quality when they start to talk about the things which they believe go to make the English—or British—national character.

Daniel Defoe was the first writer we know of to state that fair play is a part of the English make-up,1 and already his assertion was tinged by another trait often claimed as endemic to these islands: the taste for irony. Since then the two have never been far apart. Fair play is appealed to both by idealists and by ordinary people who want nothing more than reasonable treatment: but it also comes easily to the lips of blowhards and chauvinists. In 1824 a local newspaper printed some anonymous thoughts on the national character. The Englishman never hates with bitterness, wrote this unknown contributor, and

The same quality makes him carry fair play into all his quarrels. He does not quibble like the Scotsman, or bully like the Hibernian. He does not take

advantage of his antagonist when off his guard, nor come upon him with a combination of superior numbers. He demands a clear space, stands up manfully; seeks fair play; fights like a lion; when overcome, he surrenders with a good grace; and as he is not cast down by a fair defeat, so neither is he insulting when he wins an honourable victory This independence and desire of fair play descends to the very school-boys and children in the streets. You never meet with the boy who is rich hiring auxiliaries against the boy who is poor; as little do you find the cunning leaguing against the candid. It is arm in arm, no foul play; and the stronger, whatever be his rank, is the victor.2

Others, even then, had wider conceptions of fair play: they wanted to see it applied to social justice, to the workings of the law, and to Britain’s relationship with the rest of the world, and they demanded that it should be applied equally to men and women. But when people claimed fair play as an English, or indeed a British, quality, they were more often than not thinking of the way in which fights and games were conducted. Consequently the very idea of fair play, even when used by women writers, had until comparatively recently a strong masculine tinge.

Fair play has been so widely invoked in British culture—and so much taken for granted by most of those who have done so—that it could almost be called a meme, a self-contained cultural unit with a life of its own. The main aims of this book are to ask to what extent it has a core meaning; and, if there is any, where we are to look for its origins and how we are to distinguish it from the ways in which other cultures have thought about what it means to treat people equitably. One starting point is the very persistence of the tradition: as we have seen, for at least three centuries many English people, in particular, have believed that the phrase “fair play” sums up what they most value about their national culture. Another is that, perhaps more surprisingly, many foreigners have agreed. The Spanish diplomat and historian Salvador de Madariaga made a comparative study of his own compatriots, the English, and the French:

We shall observe in each of these three peoples a distinctive attitude which determines their natural and spontaneous reactions towards life. These

reactions spring in each case from a characteristic impulse manifesting itself in a complex psychological entity, an idea—sentiment force peculiar to each of the three peoples, and constituting for each of them the standard of its behaviour, the key to its emotions, and the spring of its pure thoughts. These three systems are: In the Englishman: fair play. In the Frenchman: le droit. In the Spaniard: el honor. We will notice at the outset that the three words which represent our three systems are untranslatable. Fair play has no equivalent either in French or Spanish.3

My contention in this book is that there is indeed in British culture a deep layer of attitudes and customs which are grouped together under the heading of fair play. Anyone who rejects this conclusion would need to offer an alternative explanation as to why fair play occupies such a prominent place in British discourse across the centuries. Equally, however, anyone arguing as I do must show why, if the culture of fair play runs so deeply, so much of the history of this country (as indeed of every other) consists of innumerable examples of brutal unfairness committed by the strong upon the weak; and why it would be hard to claim that British people, any more than anyone else, are paragons of fair play in ordinary life. I offer my answers to those important questions, and suggest how and why the idea broadened to encompass the rights and interests of women and of other races, in chapters 11 and 13.

It is striking that England should be the only country to have acquired an epithet which charges it with a systematic denialof fair play: “perfidious Albion”. The phrase was first used in 1793 by a French poet engaged in stoking up national fervour for the war just declared against Great Britain. A hundred years earlier the Catholic theologian Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet had written of “la perfide Angleterre”, referring apparently to the English renunciation of allegiance to the Pope at the Reformation. In the 19th and early 20th centuries “perfidious Albion” or its equivalents in French and German were often invoked by apologists for Britain’s imperial rivals or by advocates of colonial independence.4 Great-power rivalry was of course never conducted under rules approximating those of cricket, as the advocates of Machtpolitik well understood,5 but anyone seeking to show that British foreign policy was, in

comparison with its competitors, conspicuously self-serving and contemptuous of international norms would face no easy task. “Perfidious Albion” trips off the tongue, but it has generally formed part of the history of propaganda rather than of international relations.6

The culture of fair play on which the British congratulated themselves goes back much further than most people might imagine. “There can be no doubt”, says Professor Norman Davies, “that organized sport and the accompanying sporting ethos was largely a product of the United Kingdom in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries”. “It was during the Napoleonic Wars at the start of the nineteenth century”, argues Professor Tony Collins, “when British ideas of ‘fair play’ first emerged to counter the French Revolution’s ‘Liberty, Equality, Fraternity’, that sport became fused with British nationalism.”7 Davies is right, of course, to imply that the continuous history of organised sport begins in the 18th century, but we will see that the late medieval tournament both in literature and reality had many of the essential elements we associate with modern sport.8 My claim, made on the basis of inevitably sparse evidence, that the origins of fair play in Britain are hundreds of years older even than that may or may not persuade the reader. But the quantitative analysis I have carried out of the use of the term “fair play” in British printed sources proves beyond doubt, I believe, that it was being used regularly in its modern sense by Shakespeare’s time and that it was already regarded as a key element in the makeup of the British a hundred years later.

If there is indeed a tradition of fair play, does it have an opposite pole, a tradition which celebrates the skills of stealth and deception? The answer is clearly yes, and for many English people it is embodied in one man. Martin Amis described it well when he meditated on the game in which Argentina ejected England from the 1986 World Cup finals:

In South America, it is sometimes said, or alleged, that the key to the character of the Argentinians can be found in their assessment of [Diego] Maradona’s two goals in the 1986 World Cup. For the first goal, christened

“the hand of God” by its scorer, Maradona dramatically levitated for a ballooned cross and punched the ball home by a cleverly concealed fist. [For the second goal] Maradona, as if in expiation, put his head down and seemed to burrow his way through the England team before flooring Shilton [the England goalkeeper] with a dummy and stroking the ball into the net. Well, in Argentina, the first goal, and not the second, is the one they really like. For the Argie macho (or so this slanderous generalisation runs) foul means are incomparably more satisfying than fair.9

Slanderous generalisation or not, a similar observation had been made many years earlier by the French theorist of games Roger Caillois, who like Amis had spent much time in South America. Golf, he wrote, “the Anglo-Saxon sport par excellence” (a description calculated to raise eyebrows north of the border), is “a game in which a player has the opportunity to cheat at will, but in which the game loses all interest from that point on. It should not be surprising that this may be correlated with the attitude of the taxpayer to the treasury and the citizen to the state”. By way of contrast, “no less instructive an illustration is provided by the Argentinian card game of truco, in which the whole emphasis is on guile and even trickery, but trickery that is codified, regulated and obligatory”. Two pairs of partners, he explained, play against each other and the members of each pair must communicate between themselves which cards they hold while deceiving the other side. Caillois went on to suggest that this could be reflected in what he considered Latin American traits such as “the recourse to ingenious allusions, a sharpened sense of solidarity among colleagues, a tendency towards deception, half in jest and half serious, admitted and welcomed as such for purposes of revenge”.10

It seems that we have here two opposing codes of honour: in one the use of cunning to defeat an opponent is tolerated and even celebrated; in the other it is forbidden. That opposition goes back to the dawn of western civilisation, to the figure of Odysseus “the many-wiled”. Celebrated by Homer, Romans often affected to disdain his exploits of cunning in the name of a higher morality. Odysseus has had many successors, most of them not heroic warriors but more humble people, struggling to make a living on the margins

between sharp practice and outright dishonesty. They form a tradition of their own in European literature, the picaresque, their stories often told in the first person: Guzmán de Alfarache, living on his wits in 16th-century Spain, Gil Blas, his more polished successor a century later, or Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov buying up the rights to “dead souls” in some unspecified but certainly dishonest moneymaking scheme in tsarist Russia.

The tradition was known in England too. Thomas Nashe’s Jack Wilton, “the Unfortunate Traveller”, stealing and cheating his way through baroque Italy to keep body and soul together, was one of the first. He was followed by Daniel Defoe’s sympathetic tricksters, Moll Flanders and Colonel Jack, by Thackeray’s Becky Sharp, and by Arnold Bennett’s resourceful Denry Machin. The existence of an English picaresque tradition is a salutary reminder that there is nothing monolithic about the tradition of fair play: it may have been the dominant note in English culture, but there was always a space for those who chose to celebrate the skills of the trickster. Shakespeare was quite capable of giving us both Hector, the paragon of fair play, and Autolycus, the “snapper-up of unconsidered trifles” who, “having flown over many professions…settled only in rogue”, and, surely not coincidentally, bore the name of Odysseus’ grandfather.11

Regardless of their own practice, most people believe fair play to be desirable; and, while pointing out examples of its use to mask special interests or vicarious enjoyment of violence, the analysis in this book, to my mind, shows how deeply rooted that belief is. It relies mainly on historical evidence: in other words it offers what has been called a genealogical account, one that analyses fair play primarily by tracing the way in which people have written about it and practised or failed to practise it (though one which seeks to take a more objective approach than the great archetype of the genre, Nietzsche’s OntheGenealogyofMorals).12 Nonetheless, wherever it has seemed useful to bring in theory from the social sciences, evolutionary biology, and philosophy I have tried to do so. At various points the ideas of the sociologist Norbert Elias and the philosopher

Peter Singer provide structure for the argument, while briefer references are made to the insights of Alexis de Tocqueville, Karl Marx, Max Weber, the Johan Huizinga of Homo Ludens, Michel Foucault, John Rawls, and, just now, Roger Caillois. In the end, however, whatever claims to originality the book may have are based on its analysis of the ways in which people actually spoke about fair play over the centuries and in which their actions and beliefs reflected or failed to reflect it.

George Orwell once noted, in discussing wartime rationing, that “experience shows that human beings can put up with almost anything as long as they feel that they are being fairly treated”.13 There is evidence that this does not apply only to humans. One recent study suggests that in a variety of animal species the development of fair play among juveniles, such as role reversal or self-handicapping, inculcates habits of pooling scarce resources for the benefit of the group as a whole.14 Another documents the prevalence of “inequity aversion” among dogs and wolves as well as non-human primates: it appears that dogs show signs of discontent if they do not receive the same rewards as their fellows when they exhibit the same behaviour, and the same effect can be observed among wolves, indicating that it goes deeper in biological terms than the effects of domestication.15 The distinguished primatologist Frans de Waal has argued that apes and indeed many other kinds of animals have developed a crude sense of justice and fairness.16

How then does this square with the theory of the “selfish gene” which impels its possessor all of us—to act in ways which maximise its chances of successfully reproducing itself? One answer is given by Peter Singer in his theory of the expanding circle, a remarkable fusion of ethical philosophy and evolutionary biology which draws on the concepts of reciprocal altruism and kin selection developed by Robert Trivers and William Hamilton respectively.17 Singer begins with the question of how altruism can persist in our species over generations at all, since on the face of it such behaviour is likely to benefit other individuals and hence disadvantage the altruist in the struggle for survival. Singer’s response is that we share 50% of our

genes with our siblings, 25% with our first cousins, and so on: thus in a group based on kinship an individual with a gene for altruism might well, by unselfish action, enable the survival and eventual reproduction of several other individuals with that same gene. If “kinship altruism” increases the overall chances of survival of all members of the kinship group, the same effect might be generated in wider groups through the practice of “reciprocal altruism” (or, as Singer does not call it, fair play) in which each member of the group is genetically predisposed to aid every other member, even at risk of personal harm, because he or she would expect the same to happen if the roles were reversed. But there can only be assurance of such “group altruism” within defined groups whose members are known to each other: we will consider later Singer’s proposal as to how such behaviour could become embedded in ever-widening populations.18

We find that economists and evolutionary biologists have agreed that a feeling for fairness is deeply etched within our psyches. The economist Ken Binmore has written of “the evolutionary origins of the human fairness norms that lie at the root of our notions of justice”. Among anthropologists Lionel Tiger and Robin Fox saw children’s play, participation in games of skill and chance, and observation of rules as fundamental human traits, while Donald Brown included an understanding of reciprocity in his list of human universals.19 Edward O Wilson has written of how contract formation “pervades human social behaviour…like the air we breathe”, and of how our sensitivity to those who renege on their obligations is correspondingly acute. The behavioural economist Robert Frank has reached broadly similar conclusions, while Richard Dawkins has entered a strong protest against interpretations of his “selfish gene” thesis which assume that it treats self-seeking behaviour as inevitable.20

But if this were the whole truth about the way in which people in groups behave towards each other, this book could end here. Fair play would be as natural as breathing, and a history of breathing could prove monotonous. We know, however, that the world is not

like that. Social and selfish behaviours coexist. Dominant males in many species seek to monopolise opportunities to breed. No human society of any size, it seems safe to say, has ever banished aggression and inequality for long. The instinct (if that is the right word) for fair play vies with other drives, some of which may be socially constructed (such as prejudices against other classes or races) while others are surely basic. In societies where resources are scarce, in particular, “the better angels of our nature”, to use Steven Pinker’s phrase, may struggle for a hearing. The history of fair play can be seen as the history of the extent to which they succeeded.

There are also dangers in adopting, as I have done, a predominantly British focus. Since the primary questions which the book sets out to address are the extent to which the British have defined themselves by their attitude to fair play and the degree to which their protestations were matched in reality, a concentration on British evidence is inevitable. But if that evidence suggests, as it seems to, that the idea of fair play has played an unusually prominent part in British culture, the danger of conscious or unconscious nationalist bias needs to be borne very much in mind. Wherever possible I have tried to suggest comparisons with foreign cultures, whether to point out telling differences or similarities. France in particular, from whose civilisation Britain has taken so much over the last millennium, offers numerous points of triangulation which it would be foolish to ignore, but cultures all over the world have much to teach us about attitudes to fair play.

The story presented in this book covers nearly three thousand years. There is a danger that it could become not only a “genealogical” but also a “teleological” narrative:21 one that not only traces the development of its theme over a long period but also explicitly or implicitly assumes its inevitability. My analysis suggests that this is at least half-true: that habits of fair play tend to develop as societies become wealthier and more educated, and that while they may initially be confined to members of a particular social class or race they may be progressively extended as economic and intellectual progress continues (see in particular chapter 11). But

some of the great events of our own time—notably the Coronavirus pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine—have administered sharp reminders that such historical processes can be reversible, and that hardship and stress can produce examples both of abject meanspiritedness and of unexpected selflessness.

What do we mean when we talk about fair play?

Fair play is not an easy concept to pin down. In the next chapter we look at how its meaning has developed over the centuries, but here we consider what it means in Britain today. In contemporary British usage fair play means one of two things. Increasingly, as we will see in the next chapter, it crops up in the phrase “fair play to” someone, meaning a general expression of unenthusiastic congratulation, benevolence, or merely lack of animosity; but for the purposes of this chapter, and this book generally, we concentrate on the other meaning, the one which conveys the idea of right and honourable conduct both in games and in a wide variety of other situations.

Let us start with the idea of fairness before we consider how fair play might add to it. I am said to show fairness when I treat someone as they deserve. This means taking all relevant factors into account and not showing partiality either for myself or for others. Thus I may be being fair (or unfair) when I make a favourable or adverse judgement upon a person, or when I decide to pay him or her a specific amount in relation to others. Instead of talking about fairness, we may talk about being just, or showing justice, when judgements of this kind are made in the context of a framework of

law or of some other relatively formal process. Philosophers have long distinguished between commutative justice, when a person is found guilty or not guilty of some infraction and punished if appropriate, and distributive justice, when goods or benefits are assigned among a group of people in accordance with equitable principles:1 this distinction can be applied to fairness as well. Justice and fairness, then, are basically the same idea, but by convention we often tend to speak of justice in more formal or serious contexts.2 (There is an analogy here with the way we use the words “guilt” and “embarrassment”: the feeling they describe is at bottom the same, but the former tends to be used when we are thinking of weightier matters, while “shame” comes somewhere in the middle.)

When I make a sound judgement that a person is reliable or unreliable, or decide on good grounds to offer or not to offer a person a job, or reciprocate a favour which someone has done me, this is called fair. But these are not the kinds of situation we immediately think of when we hear the phrase fair play. We often think of fair play as arising in the context of a game or contest. “Play” suggests participation in a game, of course, but it can go wider; it also has the sense of “operation” (as in “the forces at play”), and the concept of fair play is also invoked when people oppose each other in contexts other than games: argument, brawling, and warfare, for example.3 The idea of play has a strange doubleness:4 it suggests freedom, almost anarchy, the wide roaming of the imagination we see, and value so highly, in the make-believe games of small children. But, at least once early childhood has been left behind, it also implies the existence of a framework of rules or expectations governing our actions. Games which are not pure make-believe make sense only within such frameworks. I can’t move my rook diagonally when it suits me, or demand to remain at the wicket when my middle stump has been taken out by a fair delivery.5 The primary meaning of fair play, I believe, derives from this sense that play implies expectations: it is the performance of a duty to abide by the rules, written or unwritten, of a contest in which we participate, a duty that we owe to, and are owed by, others

participating in that contest. (In the next chapter we will note that historically it had an alternative meaning, that of an absence of external restraint, free rein, or, as we might now say, “free play”, although that sense is only marginally relevant to the theme of this book.) But this primary meaning has a number of ramifications which need to be distinguished.