AnEndangeredHistory:Indigeneity,Religion,and PoliticsontheBordersofIndia,Burma,and Bangladesh1stEditionAngmaDeyJhala

https://ebookmass.com/product/an-endangered-historyindigeneity-religion-and-politics-on-the-borders-of-indiaburma-and-bangladesh-1st-edition-angma-dey-jhala/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Vernacular Politics in Northeast India: Democracy, Ethnicity, and Indigeneity Jelle J.P. Wouters (Ed.)

https://ebookmass.com/product/vernacular-politics-in-northeast-indiademocracy-ethnicity-and-indigeneity-jelle-j-p-wouters-ed/

ebookmass.com

Hobbes On Politics And Religion Laurens Van Apeldoorn

https://ebookmass.com/product/hobbes-on-politics-and-religion-laurensvan-apeldoorn/

ebookmass.com

Land Acquisition and Compensation in India: Mysteries of Valuation 1st ed. 2020 Edition Sattwick Dey Biswas

https://ebookmass.com/product/land-acquisition-and-compensation-inindia-mysteries-of-valuation-1st-ed-2020-edition-sattwick-dey-biswas/ ebookmass.com

ISE Introduction to Mass Communication (ISE HED B&B JOURNALISM) 11th Edition Stanley J. Baran

https://ebookmass.com/product/ise-introduction-to-mass-communicationise-hed-bb-journalism-11th-edition-stanley-j-baran/

ebookmass.com

We the People 12th Edition Thomas E. Patterson

https://ebookmass.com/product/we-the-people-12th-edition-thomas-epatterson/

ebookmass.com

Principal's Off-Limits Nanny: A Small-Town Ex Boyfriends Dad Romance Elise Savage

https://ebookmass.com/product/principals-off-limits-nanny-a-smalltown-ex-boyfriends-dad-romance-elise-savage/

ebookmass.com

Smith and Roberson’s Business Law 17th Edition Richard A. Mann

https://ebookmass.com/product/smith-and-robersons-business-law-17thedition-richard-a-mann/

ebookmass.com

And Maybe They Fall In Love Emma Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/and-maybe-they-fall-in-love-emma-hill/

ebookmass.com

Life Span Development: A Topical Approach 3rd Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/life-span-development-a-topicalapproach-3rd-edition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

Water Quality in the Third Pole:The Roles of Climate Change and Human Activities Chhatra Mani Sharma

https://ebookmass.com/product/water-quality-in-the-third-poletheroles-of-climate-change-and-human-activities-chhatra-mani-sharma/

ebookmass.com

An Endangered History: Indigeneity, Religion, and Politics on the Borders of India, Burma, and Bangladesh

Angma Dey Jhala

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780199493081

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780199493081.001.0001

Title Pages

Angma Dey Jhala

(p.i) An Endangered History (p.ii)

(p.iii) An Endangered History

(p.iv) Copyright page

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in India by Oxford University Press

of

2/11 Ground Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002, India

© Oxford University Press 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

First Edition published in 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

ISBN-13 (print edition): 978-0-19-949308-1

ISBN-10 (print edition): 0-19-949308-1

ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-0-19-909691-6

ISBN-10 (eBook): 0-19-909691-0

Typeset in Bembo Std 10.5/13 by Tranistics Data Technologies, New Delhi 110 044 Printed in India by Nutech Print Services India

Access brought to you by:

of

An Endangered History: Indigeneity, Religion, and Politics on the Borders of India, Burma, and Bangladesh

Angma Dey Jhala

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780199493081

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780199493081.001.0001

(p.v) Dedication

Angma Dey Jhala

For my mother, and her dreams of home (p.vi)

Access brought to you by:

Page 1 of 1

An Endangered History: Indigeneity, Religion, and Politics on the Borders of India, Burma, and Bangladesh

Angma Dey Jhala

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780199493081

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780199493081.001.0001

(p.ix) Figures, Tables, and Maps

Angma Dey Jhala

Figures

2.1‘My House on Sirthay Tlang above Demagree on the Kurnapoolee River, Chittagong Hill Tracts.’46

2.2‘My Bungalow on the Hill at Chandraguna, Chittagong Hill Tracts.’63

2.3‘T.H. Lewin with the Seven Lushai Chiefs Who Accompanied Him to Calcutta (1873).’84

4.1‘Rangamati Lake.’168

4.2‘Family Portrait (Bohmong’s Son and Wife).’183

4.3‘Three Women with a Child.’194

4.4‘Woman Pounding Rice.’195

4.5‘Portrait of a Man (A Boy, Basanta Pankhu Kuki).’195

Tables

3.1‘Return of Nationalities, Races, Tribes and Castes, in Each Division of the Chittagong Hill Tracts’126

3.2Censuses in the CHT, 1872–1901140

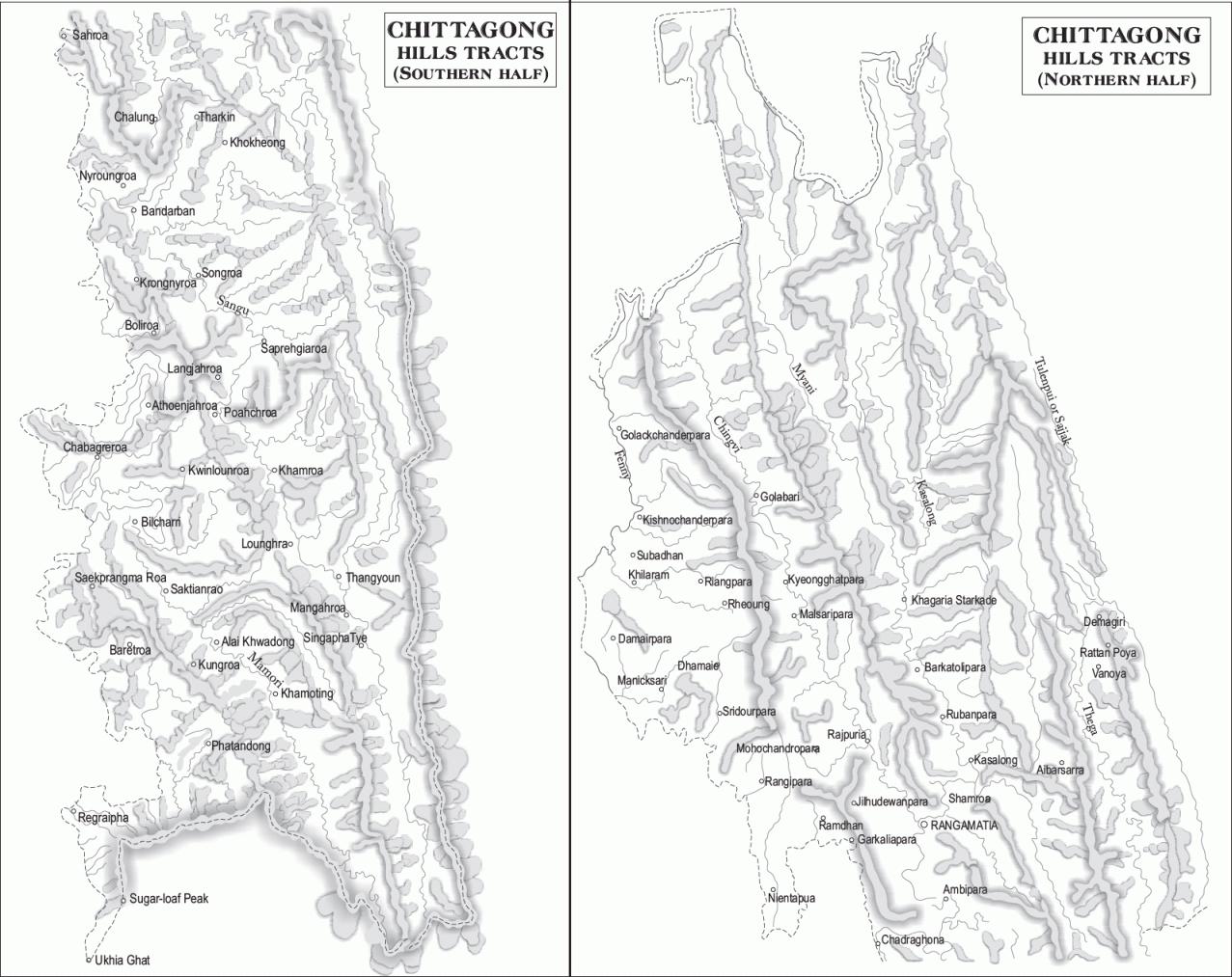

Maps

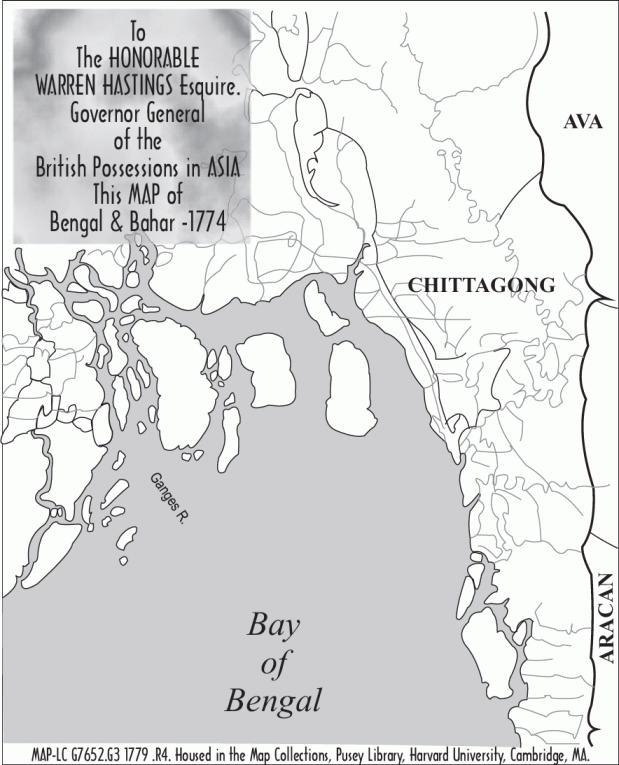

IJames Rennell, Map of Colonial Bengal and Arracan Border.

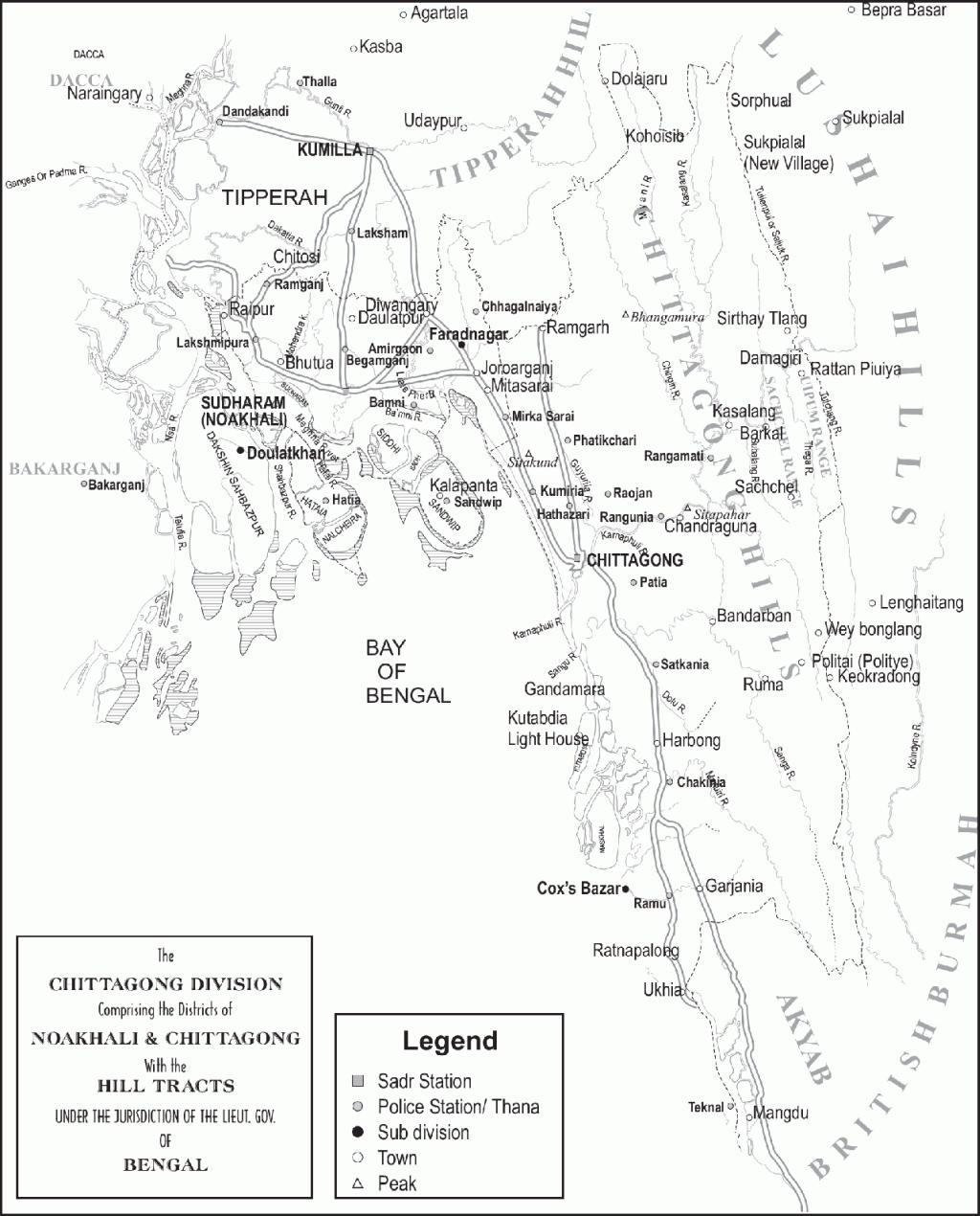

II‘The Chittagong Division Comprising the Districts of Noakhali and Chittagong with the Hill Tracts under the Jurisdiction of the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal.’

IIIChittagong Hill Tracts, 1890. (p.x)

Access brought to you by:

An Endangered History: Indigeneity, Religion, and Politics on the Borders of India, Burma, and Bangladesh

Angma

Dey Jhala

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780199493081

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780199493081.001.0001

(p.xi) Acknowledgements

Angma Dey Jhala

I first considered writing on the Chittagong Hill Tracts as a newly arrived doctoral student at Oxford in 2001. At the time, much of the scholarship (and news coverage) on the region focussed on insurgency movements and human rights violations, and less on the history, particularly the colonial history, of the east Bengal and Burma border. While intrigued, I would go on to focus on another research topic, which would preoccupy me fruitfully for the next 15 years, but I remained haunted by the untold story of the Hill Tracts. The intervening period has witnessed the opening up of archives on northeast India and east Bengal as well as the publication of dynamic new histories on the larger borderland region. This work contributes to this emerging discourse on an oft forgotten area and its peoples.

Several people, institutions, and funding agencies have been invaluable in their support of the research that went into this book, as well as my earlier work. David Washbrook was a supportive and generous doctoral supervisor, and he remains a kind mentor until today. Shun-ling Chen, Ayesha Jalal, Norbert Peabody, Jayeeta Sharma, and Willem van Schendel have expressed interest in this project at different stages.

I wrote this book as a faculty member in the History Department at Bentley University, and it is with deep gratitude that I thank my institution. Bridie Andrews and Marc Stern, my department chairs during this time, as well as my dean, Dan Everett, were encouraging, supportive, and thoughtful mentors throughout this endeavour. Conversations with my colleagues Chris Beneke, Sung Choi, Samir Dayal, Ranjoo Herr, Cliff Putney, Kristin Sorensen, Leonid Trofimov, (p.xii) and Cyrus Veeser have provided much insight and pleasure

over the years, and I thank them for creating a warmly collegial and engaging environment to teach and work.

A number of institutions and funding agencies have generously assisted in the writing of this book. Faculty summer grants and a faculty affairs grant from Bentley enabled me to examine university and government archives and cover permission costs for my book. Student research assistants from Bentley’s Valente Center, Mihir Saxena, Rijul Hora, and Ei Shwe, in 2012 and 2014–15, were vital aids, transcribing and annotating often nearly incomprehensible hand written archival manuscripts, with sunny dispositions. In particular, a sabbatical in 2015–16 provided me the intellectual freedom and time to write a full draft of the book. Much of that year was spent as a visiting scholar at the Studies on Women, Gender, and Sexuality department at Harvard University, where I was kindly welcomed by Afsaneh Najmabadi. The resources at Harvard, particularly access to libraries, university archives, and the fellowship of likeminded scholars, aided enormously in the writing of this book.

A book that dwells in the archives, as this does, is indebted to the painstaking work of librarians, who preserve repositories not only over decades but generations, despite the vicissitudes of time. I benefitted exponentially from the thoughtful help of archivists who assisted in copying and scanning delicate materials, answering bibliographic questions, tracking down ever-elusive documents, images, and maps, and giving permissions to reproduce images. I thank the Oriental and India Office Collections, British Library, London; the Senate House Library, London; the SOAS Archives and Special Collections, London; the Centre of South Asian Studies Library, Cambridge; the Pitt Rivers Museum Collection, Oxford; Harvard Map Collection, Cambridge, MA; Harvard Widener Library, Cambridge, MA; and Bentley Library, Waltham, MA. I especially thank Geraldine Hobson for graciously permitting me to reproduce images from the J.P. Mills Collection at the SOAS archives.

This book also deeply benefitted from the writings and memoir of the late Chakma raja, Raja Tridiv Roy. While I was unable to seek his counsel on certain points, his written recollections on the Hill Tracts were invaluable and broad sweeping in nature. I also thank Rajkumari Moitri Roy Hume of the Chakma raj for sharing with me her vivid, (p.xiii) detailed memories of the Chittagong Hill Tracts during a dramatic era of transition.

The arguments within this book were presented at conferences and symposia, and benefitted from the critique and encouragement of various audiences. I thank the audiences at the Historical Justice and Memory: Questions of Rights and Accountability in Contemporary Society Conference, hosted by the Alliance for Historical Dialogue and Accountability programme at Columbia Law School (December 2013); the New England Association for Asian Studies Conference,

Page 2 of 4

hosted by Boston College (January 2017); and the Bentley History Department Seminar, Of Beheaded Statues and Other Colonial Legacies (October 2017).

I also wish to acknowledge the editors at Oxford University Press, who expressed keen interest in this book at the earliest stage. I thank them and the several anonymous reviewers for championing this book.

Many friends and family have cheered me on during the writing of this book, and I am grateful for their steadfast interest throughout this process.

My dearest Mapu Chacha, while he did not have a chance to see this book, knew of its progress and sustained my heart and spirit throughout its writing. I miss him daily with a tender ache and always shall, and his love for beauty and search for sublimity in all forms remains a guide of how to live a life well. My esteemed and beloved Dadabava likewise did not have a chance to read this book, but our conversations on anthropology and ethnography, and more generally, ideas of knowledge in the past have influenced this book nonetheless. I hope he might have found this a useful attempt.

Richard Cash and Maria Hibbs Brosio are always interested and kindly supportive of what I do, and over the years, I have regaled them with accounts of this book, as well as others, which they have listened to with indulgence. I thank them for their continued love over these many decades.

My parents and Liluye have listened to many discussions about this book and witnessed its evolution from an idea to a final manuscript. My father patiently read through the complete draft of the book, giving suggestions for improvement. Liluye provided insight on various visual and technical issues. She, along with Mithun, Kesariya, Suryavir, (p.xiv) and Ayushi, has filled my days with drama, adventure, and joy, and in between writing spells, the delights of a boisterous family.

In particular, it is to my niece Kesariya that I give special thanks. She was my constant companion during much of the writing of this book, composed as it was in the darkness of pre-dawn hours and late winter nights during my sabbatical. Between school drop off and pick up, she taught me how to write on schedule with still time for laughter, love, and the always unexpected. In some magical way, she showed me books can be birthed and children reared, happily side by side.

I dedicate this book to my mother. Years ago, my mother taught me with painstaking patience how to read. Suffice it to say, I was a slow, plodding reader at first. For a book focussed on how we read and interpret knowledge, I would be much remiss to not acknowledge my first teacher. In teaching me to read, she brought the world into living, vibrant colour. Without her, I could not have

Page 3 of 4

written this or indeed any earlier work, and I thank her for this gift that never ceases giving.

And finally this book is for the people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts and all those interested in unearthing lost histories of indigenous peoples.

Angma Dey

Jhala

February 2019 Bentley University, Waltham, USA

Access brought to you by:

Page 4 of 4 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. An individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use.

An Endangered History: Indigeneity, Religion, and Politics on the Borders of India, Burma, and Bangladesh

Angma Dey Jhala

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780199493081

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780199493081.001.0001

Map I James Rennell, Map of Colonial Bengal and Aracan Border.

Source: Based on the map, ‘To the Honorable Warren Hastings, Esquire, Governor General of the British possessions in Asia this Map of Bengal and Bahar’, 1779. MAP-LC G7652.G3

Page 1 of 3

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. An individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use.

2 of 3

Note: This map is not to scale and does not represent authentic international boundaries. 1779. R4. Housed in the Map Collection, Pusey Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Map II ‘The Chittagong Division Comprising the Districts of Noakhali and Chittagong with the Hill Tracts under the Jurisdiction of the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal.’

Source: Based on the map published in W.W. Hunter, A Statistical Account of Bengal, Volume VI: Chittagong Hill Tracts, Chittagong, Noakhali, Tipperah, Hill Tipperah. London: Trübner & Co., 1876. © The British Library Board. IOR/ V/27/62/6. Official Publications, India Office Records, British Library, London, UK.

Access brought to you by:

Note: This map is not to scale and does not represent authentic international boundaries.

Map III Chittagong Hill Tracts, 1890.

Source: Based on the map © The British Library Board. Cartographic Items Maps I.S.70. Calcutta: Survey of India Offices, 1890. Reproduced by permission of the British Library, London, UK.

Note: This map is not to scale and does not represent authentic international boundaries.

Page 3 of 3

An Endangered History: Indigeneity, Religion, and Politics on the Borders of India, Burma, and Bangladesh

Angma Dey Jhala

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780199493081

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780199493081.001.0001

(p.xv) Introduction

Border Histories and Border Crossings in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bengal

Angma Dey Jhala

In the winter of 1771, an English gentleman farmer, on a brief jaunt away from his family, found a bedraggled orphan boy on the streets of Liverpool and brought him home to the dark, howling moors of Yorkshire. The boy appeared to have no discernible race; he was described at various points as a gypsy, an Indian lascar, son of a Chinese emperor, an African slave, and an American/ Spanish castaway.1 It is possible that he was abandoned on the Liverpool docks, after arriving on an East Indiaman from India, China, Malaya, or Dutch Batavia, or a slave ship from Africa or the Americas, as the port city, along with London and Bristol, was part of the teeming British slave trade.2 In his adopted home, the boy found solace in the strange and ungovernable beauty of the moors, delighting in their open spaces, running wild and undisciplined under the wide skies. His close connection to the land, coupled with his indefinable race, ethnicity and ‘gibberish’ language, rendered him uncivilized, irrational, and inhuman to the English country folk he met. He was a ‘universal “other”’ of no known origin, dangerous and violent.3 Between liminal worlds—occident and orient, metropole and colony, white and black, civilized and savage—the young man represented the foreignness of groups on the margins of colonial society and the porous, liminal frontiers of the Empire. This young man was Heathcliff, the protagonist of Emily Bronte’s classic novel, Wuthering Heights.

Wuthering Heights was published in 1847 to mixed reviews,4 but it would go on to become a significant work of nineteenth-century (p.xvi) British literature, and one that tellingly examined ideas of Victorian sexuality, identity, and class. But it is also a work that expressed British views not just of non-European others in general, but specifically those groups that could not easily be categorized

1 of

through language, race, religion, or geography. Heathcliff falls between various regional/ethnic identities: Eastern European or Irish (gypsy), South Asian (India), East Asian (China), American (North or South), and African. Many of the adjectives used to describe the young Heathcliff were not just applied to nonEuropeans as a whole, but often specifically to indigenous groups on liminal border frontiers of the Empire—areas which could not be easily contained by territorial, geographic, or political boundaries, or, for that matter, by a narrow sets of physical characteristics, social customs, or religious practices. The descriptions of Heathcliff’s naive primitivity and childlike, unwavering devotion, his cunning and cruel harshness, and his love for the untamed heath were often used to describe autochthone groups—whether Native Americans, Australian aborigines, or South Asian hill tribes—in larger narratives of imperial encounter and (mis)adventure around the colonized world.

An Endangered History is an account of one such liminal border area, the littlestudied region of the Chittagong Hill Tracts of British-governed Bengal, from the late eighteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries. The CHT lie on the crossroads of India, east Bengal (now Bangladesh), and Burma (contemporary Myanmar). It is in an area of lush rivers and fertile valleys, which has historically been celebrated for its haunting natural beauty and cultural heterodoxy—from the chronicles of Mughal governors to the ethnohistories of colonial British administrators. The region is composed of several indigenous or ‘tribal’ communities, including the Bawm, Sak (or Chak), Chakma, Khumi, Khyang, Marma, Mru (or Mro), Lushai, Uchay (also called Mrung, Brong, Hill Tripura), Pankho, Tanchangya, and Tripura (Tipra).5 They practise Buddhism, Hinduism, animism, and Christianity; are close in appearance to their Southeast Asian neighbours in Burma, Vietnam, and Cambodia; speak Tibeto-Burmese dialects intermixed with Persian and Sanskritic, Bengali idioms; and practise jhum or swidden—slash-and-burn agriculture.6 Their transcultural histories, like that of Bronte’s fictional hero, defied colonial, and later, postcolonial taxonomies of identity and difference. Indeed, both British (p.xvii) administrators and South Asian nationalists would misunderstand and falsely classify the region through the reifying language of religion, linguistics, race, and, most perniciously, nation in part due to its unique, and at times perilous, location on the invisible fault lines between South and Southeast Asia.

This book aims to re-establish the vital place of this much marginalized (and oft maligned) border region within the larger study of colonial South Asia and Indian nationalism. In the process, I argue that the region is a fertile space to analyse transregional histories, which cross the boundaries, technologies, and teleologies of state formation, colonial or postcolonial. The peoples of the region have long been engaged in transcultural relationships with neighbouring states and communities throughout Southeast and South Asia, whether for the purposes of trade, pilgrimage, or marriage, in the process defying the bounded spaces of imperial–political geo-bodies, Mughal or British, as well as later post-

Page 2 of 52

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. An individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use.

independent nation state boundaries. I suggest that studying this fluid border area reveals a number of important developments in how colonial states created and imagined porous frontier zones, and the consequences of such colonial policies on later nation state formation.

In particular, I focus on how British administrators used European knowledge systems to define this region as distinctly different, from the moment of the English East India Company’s expansion into Bengal in the mid-eighteenth century to the partition of British India and Independence in 1947. Much of this colonial archive, based upon the writings of regional district administrators, applied European-derived intellectual paradigms, whether from botany, natural history, demography, geography, or ethnography, to construct the autochthone groups of the CHT and their landscapes. In the process, such readings of the culture, religion, languages, and geography of the indigenous ‘tribes’ reveal the problems of imperial knowledge production. While there are manifold accounts by colonial administrators, serving in both British India and the princely states,7 there are few histories of political agents that have focussed on the ‘political and personal dimensions’ of colonialism, particularly in frontier areas, such as the larger northeast India border,8 in which the CHT was situated. This is one of the major contributions of this book.

These colonial interpretations were varied and diverse, far from uniform in nature, and rich with ambiguity and paradox, revealing (p.xviii) the lively debate among colonial administrators and policy makers on how best to govern and police tribal ‘others’. Complex and often puzzling, their works are filled with ambivalence, self-contradiction, and subversion—in several cases critiquing colonial rule while upholding it and praising and protecting indigenous custom while advocating Western ‘civilization’ and reform. As a result, I suggest these accounts are as much about European administrator-scholars as the groups they were trying to define in the CHT.

For this reason, the colonial archive serves not only to exhume a long-forgotten regional past, but also to illuminate a dynamic interconnected global history. In the process of describing and defining unfamiliar autochthone groups, British administrators grafted European and colonial landscapes and cultures from around the world upon the CHT, including the Scottish highlands, English countryside, German riverine valleys, wooded American frontiers, island Jamaican plantations, upland Indonesia, and Ashanti villages, among others. Nearly every account I examine included a geographic or cultural comparison with other parts of the Empire as well as other parts of the Indian subcontinent. In response, tribal peoples from the CHT both resisted and adopted aspects of colonial culture and governance, and their chiefs increasingly saw themselves as global cosmopolitans by the early twentieth century, crossing both constructed geopolitical borders as well as imperial subjectivities in the way they constituted and reconstituted identity. Their life histories reveal that indigenous voices, long

Page 3 of 52 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. An individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use.

assumed to be marginal and peripheral to colonial power, were engaging or attempting to engage with power systems at the imperial centre.

Such ideas of transregionalism, both within and outside the subcontinent, would become increasingly contentious in the twentieth century with the rise of the Indian nationalist movement. The politically charged language of nationalism left a troubling legacy on this multi-ethnic, multireligious, and multicultural border area. The indigenous peoples, who were primarily Buddhist (as well as Hindu and animist), were sidelined during the nationalist movement, which emphasized majority Hindu and Muslim constituencies. While the leaders of the CHT petitioned to join either India or Burma during the 1930s and 1940s—nations with whom they shared historic and contemporaneous cultural and religious ties —the region was placed in Muslim-majority (p.xix) East Pakistan in 1947 (subsequently Bangladesh after the Bengali war of liberation in 1971). In the following period, the indigenous peoples suffered widespread statemanufactured violence and human rights violations, including ethnocide, genocide, forced conversion to Islam, destruction of Buddhist and Hindu places of worship, inundation of thousands of miles of arable land with the building of dams, rape, massacre, and forced migration in the second half of the twentieth century, mostly because they were seen as non-native others—more Southeast Asian than Indian (or later Bengali)—in ancestry and culture. Examining the decades leading up to Partition is one way to re-remember these groups who have often been excluded and forgotten as ‘stateless’ silents9 in the violent tectonic shifts of Partition and nation state building. Largely overlooked in mainstream histories of Indian nationalism, I suggest that a study of the CHT would further broaden our understanding of Partition, particularly in Bengal. In addition, recovering its colonial past would shed light on the postcolonial history of a Buddhist minority in a contemporary Muslim-majority nation state, of which there are few similar studies.10 Before delving further, I will briefly address here the CHT’s transregional past.

Historical Overview

Pre-colonial Border Crossings, Burmese, Mughal, European: Through Mountain Passes and across Ocean Routes

Originally a remote hinterland of the colonial province of Bengal, the CHT was a fertile meeting ground for Indo-Persian tradition, indigenous tribal cultures, and European influence, belonging to a larger geography that stretched across Assam, Tibet, Kashmir, Nepal, Burma, and western and southern China.11 For centuries, foreign merchants—whether Armenian, Afghan, Shan, or European— traded with Bengalis, Khasis, Cacharis, and Manipuris in this larger border region with Burma.12 Goods and people moved between hill and lowland societies throughout northeast India, as merchants, pilgrims, and migrants travelled between western Assam, northern Bengal, Bhutan, Tibet, Cooch Behar, Rangpur in Goalpara, and the foothills of the Himalayas in a porous and flexible environment of ever shifting political frontiers.13 During the colonial period, the

Page 4 of 52

overland trade route with China appealed to both private investors and corporations connecting, as it (p.xx) did, east Bengal to Yunnan province in China, Burma, Manipur, and Cachar.14 European merchants were eager to find markets for their own goods as well as gain gold, elephant tusks, pepper, lacquer, hardwoods, cotton, and highly prized wool shawls, which were valued at up to a thousand rupees in Mughal India, Tartary, Persia, and Arabia.15

This transcultural engagement reflected a dynamic intermingling of religious practices, including Hinduism, Sufi Islam, Buddhism, Christianity, and Judaism, from the early medieval era up through the twentieth century. Medieval accounts describe relationships between Afghan soldiers, Mughal-Rajput commanders, Tibetan-speaking Buddhist Tantric kings, and Portuguese sailors in the area as well as the role of northwestern Indian merchants and bankers in spreading Hindu and Buddhist doctrines and Ismaili forms of Islam. Records of the Surma-Barak river systems chronicle communities practising conjoined forms of Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and tantric Buddhism living peacefully side by side, while narratives of the religious and cultural traditions of the Chakmas from the CHT note the incorporation of Hindu worship and ritual into their Buddhist practices.16

The port city of Chittagong in many ways reflected this cosmopolitanism, connecting the region to Mughal India and the larger Indian Ocean economy. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, metropolitan Chittagong and its surroundings served as a ‘frontier’ between Mughal India and the monarchic state of Arakan in Burma.17 The port attracted foreign capital and empire builders, in addition to the Arakanese and Mughals, including the Portuguese, Afghans, Pathans, and eventually the British.18 Christian slaves and fugitives from Goa, Ceylon, Cochin, and Malacca settled in Chittagong and were gifted land grants by the king of Arakan. These Portuguese merchants engaged in piracy and plunder of coastal villages19 via river pathways into inland Bengal and Burma,20 undermining Mughal control in the process. Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, Malay, Arab, Persian, and Dutch merchants also traded in its harbours and on its streets.21 Chittagong thus saw a rich intermingling of diverse cultures, reflected in the cosmopolitanism of medieval mainland Burma as well.

The Arakan or Rakhine state, which controlled Chittagong, was, as Rishad Choudhury argues, ‘a paragon of the early modern cross-cultural polity’.

Consolidated in 1430, it was nominally a Theravada Buddhist kingdom, and its capital, Mrauk-U (Myohaung), was located (p.xxi) on the eastern littoral of the Bay of Bengal. The Mrauk-U dynasty incorporated various aspects of the material culture and ceremonial of Indo-Islamic courts, including the patronage of a Persianate Bengali literature and adoption of Persian titles, alongside Buddhist practices and Burmese honorifics. Such rich cultural fusion was expressed in the works of the Bengali poet, Alaol (c. 1607–1680), who served at

Page 5 of 52

the Arakan court, and evocatively described the region’s multi-jati22 hybridity and its location in a diverse Burmese coastline.23

The Mughals themselves were unsure exactly where the city and its surroundings fell. They had trouble particularly in classifying the Arakan polity in religious terms, for the royal dynasty did not practise the familiar faiths of either Islam or Hinduism. Emperor Akbar’s court chronicler, Abu’l Faz’l, while noting that the city and region around it lay in Arakan, at the same time ambiguously situated it under Akbar’s revenue administration.24

Mughal Intrusions: Imperial Sovereignty and Local Autonomy

It was eventually the Mughal distaste for Arakanese slave raiding that instigated formal imperial conquest. After two failed invasions of Chittagong in 1617 and 1621, and various threats through the 1630s, when the Mughal governor of Bengal warned Arakan that the entire region of Chittagong and Rakhang would come under Mughal suzerainty,25 Chittagong fell in 1660. Shaista Khan annexed Chittagong that same year.26 It formally became part of provincial Bengal under Nawab Murshid Quli Khan (r. 1716–1727) in the early eighteenth century.27

This growing Mughal influence would not only affect coastal Chittagong but also the hill tribes further inland, although more indirectly. While the Mughals gained influence in Bengal from the sixteenth century onwards, with Akbar’s annexation of Bengal in 1574, Shah Jahan’s appointment of his son Shah Shuja as governor of Bengal in 1639, and the later 1660 annexation of Chittagong,28 most British colonial records noted that there was little direct intervention by the Mughal state in the CHT until the eighteenth century. Indeed, the powers and territories of the local tribal rajas or chiefs remained largely autonomous throughout Mughal rule and the hill tribes were mostly untouched. In part, this may have been due to the fact that the CHT had a small population who practised jhum agriculture, which had little (p.xxii) surplus, making it less attractive for imperial control by the Mughals or neighbouring Chittagong, Arakan, and Tripura.29

This period reflected not only the gradual spread of Mughal political and economic systems, but perhaps more importantly, the sustained role and salience of local dynastic power, manifest through significant alliances between regional states within the area. Local rajas, such as the rulers of Bijni, Cooch Behar, the Ahom court in contemporary Assam, Bhutan, and the Dalai Lama of Tibet,30 as well as the rulers of Tripura, Manipur and the CHT tribal chiefs,31 formed important interregional alliances with each other, as well as with the imperial centre. Such connections reflected the abiding importance of local ideas on territoriality and sovereignty. Furthermore, when the rajas of Bijni, Sidli, and Karaibari in northeast India, for instance, received the elevated rank of peshkari zamindars from their Mughal overlords, their titles not only symbolized their traditional status in the eyes of the emperor, but also their

6 of 52

substantial military influence, regional autonomy, and judicial authority over their own peoples32—a policy of indirect rule which would continue under the English East India Company.

A passage from the Tripura Rajmala, the genealogical poem of the royal Manikya dynasty of Tripura, recounts some of these ambiguities of sovereignty through one princely encounter. In this episode, the Mughal prince Shah Shuja took refuge at the court of a local tribal ruler, the Magh raja (possibly Raja Candasudhammaraja), at the same time that his neighbour, the Tripura king, Raja Govinda, was also visiting due to a dynastic conflict at home. Upon Shah Shuja’s arrival, Raja Govinda stood and invited the Mughal prince to take his kingly seat (siṃhāsan) (the Sanskrit word for seat serving as a metonym for royal throne). The Magh raja turned to his fellow ruler, questioning why they should renounce their royal seats (material and symbolic) to a Muslim foreigner (a mlechha). Raja Govinda retorted that the Mughal prince was a paramount lord among their fellowship of kings.33

The incident reveals the influence of Mughal power in the region, but also its contested nature. By no means did the Magh raja instantly recognize the Mughal prince as his liege lord; rather he saw him as a foreign interlocutor. Mughal administrative conventions, whether relating to voluntary trade or Indo-Persian ceremonial in such settings as Darbars, would be adopted in modified form by (p.xxiii) local rulers for strategic alliance making, but alongside the continued observance of tribal authority, and local forms of agricultural production, religious ritual, customary law, inheritance, and marriage conventions, as well as a host of other social practices.34 In certain cases, there was more overt resistance.35 Indeed, there was little Mughal intervention in the CHT until 1713, when Chakma Raja Zallal Khan petitioned the then Mughal Emperor Farruksiyar (1713–19) to allow open trade between the jhumiahs (the swidden agriculturalists who peopled the Hill Tracts) and the lowland beparees (traders) on payment of a cotton tribute.36

This hybrid regional history has also influenced ideas of tribal identity and origin. Colonial administrators, scholars, and indigenous genealogists have long been divided on the historical antecedents and migration patterns of the original autochthone peoples in this porous border area. In large part, due to the ‘absence of detailed authentic records’, particularly written chronicles, it has been difficult to verify the premodern history of the region. Most genesis stories are based on oral histories and the narratives of minstrel-bards, such as the genkhuli, who recited genealogical histories over generations.37 Some claim the peoples of the region originated in southern Tibet or southeastern China before migrating to their current location.38 Others argued that they were from Malacca, a place of Malay origin.39 Yet other hypotheses suggested they had moved from Arakan in Burma40 or were the descendants of medieval mixed Mughal–Arakan marriages.41 Such genesis narratives captured the imagination

Page 7 of 52 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. An individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use.

of later British colonial administrators who from the eighteenth century onwards attempted to use such mythologies to determine and define tribal identity and otherness.42 Members of the Chakma tribe, the largest group in the region, have several origin tales, and believe themselves descendants of both Hindu and Buddhist royal dynasties. They claim ancestry from the ancient Hindu Kshatriya kings of Champanagar in Magadha, in what is contemporary Bihar,43 as well as lineal descent from the Shakyas, the gotra or clan of Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism.44 Such varying accounts reflect the diverse interconnecting histories of the CHT peoples, which crossed boundaries of religious, cultural, and ethnic typology. As the tentacles of colonial military capitalism grew, particularly under the East India Company, such fluid histories became increasingly scrutinized and more rigidly bounded.

(p.xxiv) Colonial Capital at the Borders of Empire: The East India Company and the Burmese State

By the early eighteenth century, the Mughal empire was splintering both at the centre and at the margins. Its wane saw the rise of European commercial interest. In the eighteenth century, the English, Dutch, Danish, Ostend, French, and Portuguese companies were all engaged players in the region.45 The English East India Company, which had been formed by royal charter under Queen Elizabeth I in 1600, gained rights to trade in Mughal India under Emperor Jahangir by 1619.46 It would broaden its reach in Mughal India throughout the seventeenth century, and by the eighteenth century, would adopt a militarily expansionist role in the subcontinent, in part due to the growing strength of its navies. With the decisive victory of the British commander, Robert Clive, against the nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daula, in the Battle of Plassey of 1757, the East India Company emerged as the dominant European force in Bengal. Seven years later, following the Battle of Buxar in 1764, it acquired the rights of diwani or revenue collection in Bengal from the much diminished Mughal emperor.47

In 1760, Nawab Mir Qasim Ali Khan, the Mughal governor of Bengal, ceded the province to the British. Chittagong soon became strategically significant to the Company for several reasons: it housed a bustling port, important for a naval imperial power; it was a significant commercial hub in the Indian Ocean economy; it served as a frontier district between Bengal and Arakan, which still controlled much of the nearby territory;48 and it was a shield against the increasingly muscular ambitions of Burma.49 Burmese ships were trading far and wide and Burma’s port cities, such as Pegu, were, like Chittagong, a mélange of Europeans, Persians, Armenians, South Asians, Mons, and Burmese, among others in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. By the early nineteenth century, there was a prosperous and vibrant commercial relationship between Burma and China. Burma exported cotton to China, while China sent raw silk for the Burmese weaving industry; gold and silver, which enriched the Burmese

Page 8 of 52 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. An individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use.

aristocratic class; as well as copper, sulphur, zinc, cast-iron pots and pans, paper, and various exotic goods.50

Thus, the East India Company saw the CHT and the neighbouring hill border as a strategic gateway to the riches of Burma and China, (p.xxv) and a buffer zone against both these expansionist, robust Asian states51 as well as the more recalcitrant and troublesome eastward-dwelling tribes, such as the oft-vilified Lushais/Kukis.52 In 1785, Burma invaded cosmopolitan Arakan,53 leading to the displacement of Arakanese refugees into the CHT,54 where they received support and sanctuary from local Buddhist communities. In response, the Burmese attempted to disrupt the East India Company’s local trade and revenue systems in northeast India. Burmese armies invaded Assam three times between 1817 and 1826, and after 1821, were forced to retreat during the Anglo-Burmese War of 1824–6.55 With their final victory in 1826, the British gained control over Arakan56 and became fully entrenched in the region.57 Under the Treaty of Yandabo, the court at Ava relinquished interference in the affairs of Jaintia, Cachar, and Assam, and ceded their territories of Manipur, Arakan, and the Tenasserim. It also agreed to pay an indemnity of one million pounds sterling (a vast sum for the era) and exchange diplomatic representatives between Amarapura and Calcutta.58

Company Administration: Revenue Collection and Plough Agriculture

From the start, the colonial government was concerned with extracting revenue collection from the CHT and transitioning the hill tribes from jhum cultivators to plough agriculturalists.59 These twin issues would remain primary administrative objectives throughout the colonial period, up until the twentieth century, but on both fronts the British faced strong indigenous opposition. Until 1772, the East India Company largely maintained pre-existing Mughal policies of regional non-interference, but in the period following, after Warren Hasting’s assumption of the office of governor of Fort William, the CHT increasingly came within the crosshairs of Company ambitions.60

Resisting the Company’s demand for revenue payments, the hill peoples rallied behind the leadership of the Chakma chief.61 In 1777, the British chief of Chittagong wrote to Warren Hastings that a deputy of the Chakma chief, one soldier-statesman, ‘Ramoo Cawn’, or Ramu Khan,62 had violently resisted Company landholders by recruiting and leading a fighting body of Kuki warriors.63 The Kukis, later termed the Lushais and after India’s independence, the Mizos,64 were perceived by (p.xxvi) the British as the most skilled and bloodthirsty headhunters and raiders among the hill tribes. In November 1777, the government requested British troops under the command of Captain Edward Ellesker to move against the Kuki forces.65 In the following year of 1778, the Chakma Chief Jan Baksh Khan, along with Ramu Khan and their warriors, captured Bengali talukdars, raiyats (reyotts), or cultivators, and requested the payment of nazirs (or tributes) following Mughal revenue patterns. They erected

9 of 52

neeshans (flags of independence) and would not allow the raiyats to cultivate the land.66 A decades-long war broke out thereafter, with various skirmishes in 1784 and 1785, which the British failed to win. As Amena Mohsin argues, the Chakmas had constructed a formidable military structure and strategy, using guerilla tactics of hit and run to fight the East India Company army.67

In 1787, the British finally succeeded in squelching the resistance. Jan Baksh Khan surrendered to the Company after an enforced economic blockade on the hill people. He subsequently accepted British suzerainty and agreed to pay a cotton tribute in exchange for reinstated hill–plains trade. He also agreed to keep the peace in the neighbouring border regions.68 At first, the tribute was paid in cotton, but after 1789, it transitioned into cash. In exchange, the British protected the autonomy of the Hill Tracts and the sovereignty of its indigenous leadership, largely preventing Bengali migration to the hills until 1860.69

As the commissioner of Chittagong, Mr Halhed, admitted in 1829, the British had no real ‘authority in the hills’ and revenue amounts remained modest, ‘the payment of the tribute which is trivial in amount in each instance is guaranteed by a third party, resident in our own territory, and who is alone responsible.’70 Indeed, while the amounts may have been ‘trivial’, the Company’s system of revenue collection would nonetheless have reverberations, which would in time alter the Hill Tracts. As Halhed noted, most payments were made through intermediaries—Bengali commission agents, who collected tribute from the chiefs on behalf of the Company. Bengalis now began living and travelling in the Hill Tracts as government agents, traders, and fortune-seekers.71 By the midnineteenth through the early twentieth centuries, colonial administrators observed and bemoaned the extortionate rates of Bengali moneylenders, who swindled local tribal peoples, and (p.xxvii) recounted many such incidents in their administrative reports, surveys, and memoirs. The British often disparaged the Bengalis and worked assiduously to block further Bengali migration,72 which ironically they had themselves catalyzed a century earlier. In his 1909 gazetteer, R.H. Sneyd Hutchinson noted:

The authorities do all in their power to protect the hillmen from the rapacity of the money-lenders, but it is a very difficult task to deal with these blood-suckers, and the general improvidence of the hillman renders him an easy prey to these astute rogues. A very wholesome regulation in the Hill Tracts is the one forbidding the appearance of a pleader or mukhtear (lawyer) in any court within the jurisdiction of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. This regulation has a very satisfactory deterrent effect on unnecessary litigation.73

The second major issue of contention was that of plough cultivation. From the first, the hill people resisted colonial proselytization of plough agriculture. They remained firmly rooted in jhum production, up through the mid-twentieth

Page 10 of 52 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. An individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use.

century. While Francis Buchanan (later Hamilton) noted that the soil quality was rich for plough cultivation as early as the late eighteenth century, the hill people were uninterested in colonial enticements to shift to plough farming. He even (grudgingly) acknowledged that while jhumming was ‘rude’ in nature, it had various advantages.74 Despite the British introducing a number of incentives, in 1868, merely six applications were made for plough cultivation, and by 1873, the number rose to a scant 78, which resulted in only 294 acres under investment. The deputy commissioner, in his Annual Report for 1874–5, noted numerous drawbacks, including the threat of wild animals, such as tigers, on cattle as well as other ‘wild beasts’ and birds on crops. Furthermore, the local leadership resisted such introductions as they would lose capitation tax for the hill people would thereafter pay allegiance to the deputy commissioner not the chief.75 This lack of interest persisted through the early twentieth century, when the majority of CHT residents continued to jhum as noted in the 1901 census.76

Despite such measures of control, the colonial period saw continued cultural hybridity within the region irrespective of the creation of more rigid territorial boundaries. The CHT was still governed by the chiefs, who ruled groups of people—several dozen to thousands of people in number.77 Many of these chiefs maintained connections (p.xxviii) with Southeast Asia, particularly Arakan and Burma, as they had for centuries.78 At the same time, they retained relations with neighbouring plains-dwelling Bengalis who practised various faiths such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam. In the flat lands of their territories, Chakma rulers encouraged Bengalis to settle and cultivate arable land,79 in part because plough agriculture was a form of farming that the tribal peoples would not embrace, preferring a more ‘free and wandering’ life.80 In larger northeast India, colonial borders remained porous and there was a vibrant movement of goods and people, from traders, migrants, healers, and mendicants.81

Visitors to the region observed this rich cultural heterogeneity. When Francis Buchanan first travelled through the region in 1798, he was impressed by its rich religious and cultural hybridity, which had emerged out of its multi-ethnic, multireligious past. He noted that the tribal chief, the Bohmong raja, employed both Hindu and Muslim servants, consulted a Muslim minister of state, and housed debt slaves from the Marma tribe in his household. He also collected European commodities, outfitting his royal residence with chairs, carpets, beds, mats, and other western furniture.82 During this same trip, Buchanan noticed a Chakma Buddhist priest reading a Bengali text and observed that many Chakmas spoke Bengali. Local place names were often of Sanskritic-Hindu derivation, including that of the main river, the Karnaphuli, the Chakma city of Rangamati, and the sacred hill landscapes of Ram Pahar and Sita Pahar.83 Such heterogeneity was the product of centuries of cultural exchange in the area, and was particularly highlighted in colonial accounts as stunning evidence of unusual fusion. Buchanan, who was critical of the work of contemporary British administrators in Bengal that emphasized Brahmanical Hinduism such as that of

Page 11 of 52

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. An individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use.

the Sanskritist and founder of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, William Jones, was particularly intrigued by the egalitarianism of Buddhism.84 He found such instances of religious and cultural cross-mixture both surprising and inscrutable. Indeed, as we shall see in Chapter1, the hill people befuddled him, as their cultural practices questioned his perceived beliefs on the bounded nature of religion. Such observations reveal the importance of colonial accounts as records of cultural cosmopolitanism, and the ensuing problems of later colonial reification.

(p.xxix) Post-Mutiny Reverberations: Overt Intervention under the British Raj

The nineteenth century saw more pronounced colonial intervention with the development of the British Raj. After the Mutiny or first war of Indian independence in 1857–8 and the subsequent transition from Company to Crown rule, the administration of the CHT began to change. In 1859, a raid occurred at the fort at Kaptai, and in 1860, Kukis raided and killed British settlers living in Tripura, which led to a force being sent to Barkal with the purpose of punishing the ‘offenders’.85 The region was subsequently annexed that year, formally separated from the Chittagong Administration, and thereafter declared an ‘Excluded Area’ with its own revenue and civil administration.86

There was a long prior history of raiding in the region, and the colonial government had already led a number of punitive campaigns against offending hill tribes, resulting in the direct colonial administration of the Khasi Hills District in 1833 and the Jaintia Hills District in 1835.87 Company administrators feared raiding for three primary reasons: its disruption of agricultural activities; prevention of further Company expansion; and limitations on efficient and enhanced revenue collection. The British perceived the frequency of such raids as forms of indiscipline, epitomizing ‘the “uncivil” nature of the tribes’ according to the Arakan commissioner. Colonial administrators in particular blamed the lack of unity among local elites as a key reason behind raiding, citing that raiders took advantage of internal familial disputes, for instance, those within the family of the Bohmong raja, to raid within the raja’s territory.88

To prevent raiding and to discipline the tribes, the colonial government implemented forms of indirect rule, which undermined the position of traditional leaders. Under Act XXII, the hills and forests to the east of Chittagong district were renamed the ‘Chittagong Hill Tracts’, divided into a new territory which constituted of 17,602 sq. km with a population of 63,054 and a population density of less than four persons per sq. km.89 The purpose of the 1860 annexation, according to the colonial government, was the protection of hill people from the oft-cited menace of Bengali middlemen, particularly the aforementioned attorneys and moneylenders; the preservation of indigenous ‘customs (p.xxx) and prejudices’ from foreign assimilation; and a greater

Page 12 of 52

emphasis on British courts intervening in rulings on judicial matters, particularly ‘heinous’ crimes.90

In the process, the British, while co-opting pre-existing systems of semiautonomous tribal governance, also created a bureaucracy that undermined the authority of the chiefs and was far more interventionist than in the first century of Company rule. The CHT came under the jurisdiction of a superintendent, whose headquarters were first established at Chandraghona, and later moved to the Chakma capital of Rangamati.91 In 1867, the British formally changed the official title from superintendent to deputy commissioner.92 The first superintendent of the Hill Tracts, considered an ‘eccentric’ man, was known locally as the ‘Pagla Sahib’, and was subsequently succeeded by Captain Graham and then Thomas H. Lewin, who later became the newly created deputy commissioner.93 ‘An unusual British official’,94 Lewin originally took up residence in Chandraghona, 18 miles up the Karnafuli river, on the border of Chittagong District.95 He would produce a voluminous written, visual, and photographic archive of the Hill Tracts. From the start of his administrative term, he aimed to curb the chiefs’ powers in military, political, and financial spheres. He and later colonial officials to follow would argue that the chiefs were unable to protect their own peoples from the raiding of eastward-dwelling tribes and that the indigenous hill men needed British courts to settle disputes rather than their chiefs’ rulings.96 To this end, Lewin would work to control the local chiefs or rajas. For instance, he would go on to replace the Bohmong chief, Kong Hla Nyo, with a more malleable cousin. However, he would find the Chakma chieftainess, the widowed Rani Kalindi, a much more formidable adversary.97

The rani resisted colonial intervention into local Chakma state administration, law, revenue collection, and territorial issues for years. As a way to curb the rani’s influence, Lewin elevated one of her village headmen (roaza) to the rank of chief and created the new state of the Mong raja from 653 square miles of existing Chakma raj territory.98 She fought continuously throughout this period for Lewin’s dismissal, raising a slew of charges related to mismanagement with his superiors in Calcutta, which would throw a subsequent pall over his career and lead Lewin to suggest, perhaps (p.xxxi) hyperbolically, that she was behind a botched assassination attempt on his life.99

In light of Lewin’s policies, the CHT was redrawn and subdivided into three chieftaincies in 1881: the Mong circle in the north under the newly crowned Mong raja at Manikchari; the diminished Chakma circle at the centre under the Chakma raja at Rangamati; and the Bohmong circle in the south under the third premier tribal ruler of the CHT, the Bohmong raja, at Banderban.100 In the process, the colonial government elevated these three primary or ‘circle’ chiefs, although there were several other tribal groups in the region with their own indigenous leaders. For security reasons, the district headquarters were moved

Page 13 of 52 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. An individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use.

from Chandraghona to Rangamati.101 The new district consisted of the three chiefs’ circles, initially a khas mahal or government estate, and government ‘reserved’ forests.102 Revenue collection was divided between the colonial government and the indigenous chiefs, with the British collecting rent from plough cultivators while the chiefs collected tax from jhum practitioners.103

One of Lewin’s primary administrative objectives, in addition to limiting the influence of the tribal chiefs, was dealing with the larger issue of raiding and bringing the more recalcitrant raiding tribes and headhunters to heel. Towards that purpose, he and successive colonial administrations worked to suppress the Kukis/Lushais. In 1871–2, he engaged in a successful campaign against the Lushais after an English tea plantation was raided, suffering one fatality and the abduction of several indigenous workers, including the young English girl Mary Winchester, daughter of the plantation manager.104 The raid and ensuing campaign received much publicity in the Anglo-Indian and British press of the day.105 In the period following, the colonial government created military camps to maintain ‘law and order’, and by the 1870s, there was one military policeman for every ninety-six inhabitants.106 Troops, particularly imported Gurkha forces from Nepal, Manipur, and Assam, were stationed throughout the district, their presence embodying the image of colonial discipline and dedication.107 In 1892, the Lushai Hills were annexed and the CHT became an independent subdivision of Chittagong, leading to the 1900 Regulation, at which point the Hill Tracts was reclassified as a separate district.108

(p.xxxii) Defining a Nation: Excluded Status, Local Sovereignty, and the Language of Indian Nationalism

The new district had a unique and rather tenuous position in colonial India. As Willem van Schendel notes, it became neither a princely state, as were several neighbouring semi-autonomous kingdoms with hereditary dynasties such as Tripura, nor was it a regular district under the direct control of the Government of Bengal, like that of bordering Chittagong district.109 Indeed, if this borderland had not come under colonial rule, it would have remained a ‘multi-polar-zone’ of monarchies and chieftaincies in constant competition with each other.110 Its unique status after 1900 reinforced localized traditional tax collection systems with the chiefs at the apex. Chiefs retained hereditary positions, with the ability to choose their successors, and the colonial state formally recognized the investiture of each chief up until 1947. Rajas and their village headmen received commissions on collected tax and, in return, additional land grants. Chiefs also retained jurisdiction, as they had done since Mughal times, over customary law and ‘minor legal matters’ in their circles, and chose their village headmen in the new administrative units of mauzas which the British had introduced.111

However, while the Regulation or Manual (1900), as it was called, appeared ‘favourable’ to the hill people on the surface, it eroded their sovereignty and further alienated them from the larger political environment in turn-of-the-

14 of 52

century Bengal and greater India. More power was invested in the deputy commissioner while chiefs were converted into local ‘tax collectors’.112 This redrawing of districts, annexation of lands, and subjugation of recalcitrant tribes was in large part driven by a colonial need to create firm borders and ideas of territoriality.113 An island people, the British brought a ‘seacoast view’ to frontier areas like the CHT, and felt the need for neat boundaries between different tribes and their territories. This need to create boundary lines was the impetus behind the creation of the chiefs’ circles and excluded or special status for tribal areas. However, in reality, these newly created borders were often more fluid than fixed.114 In 1920, an amendment declared the region a ‘Backward Tract’. Fifteen years later, the Government of India Act of 1935 designated the entire region a ‘Totally Excluded Area’, severing its ties with larger Bengal.115 Under (p.xxxiii) this Act, the tribal chiefs who had previously been charged with the administration of their circles now found themselves acting more as advisors to the colonial government than executive agents, with their powers acutely curtailed.116 In the process, the colonial state rigidified territorial boundaries and limited earlier, more fluid cultural exchanges through strict binaries of self vs. the other.117

Scholars such as Amena Mohsin argue that these colonial policies of territorial exclusion ultimately divorced frontier zones, like the CHT, from the developing Indian nationalist movement.118 While protected against the vicissitudes of lowland capitalists, such demarcations also created limited market and trade interactions for tribal entrepreneurs and weakened the flow of cultural and intellectual ideas from greater Bengal into the Hill Tracts, such as those of the Bengali renaissance. Earlier, there had been more movement between highlanders and lowlanders through an unrestricted hill–valley flow.119 Tribal groups now became voiceless minorities in the ensuing debate for political enfranchisement.

It was these historical forces—pre-colonial cross-border movements and colonial attempts to control, survey, and ultimately territorialize the peoples of the region —that influenced the way the region was perceived in the imperial imagination. Colonial administrators, from East India Company botanists to early twentiethcentury pukka sahibs of the British Raj, not only patrolled and policed the region, but they also recorded and romanticized it. Their ensuing writings dissected and deciphered the Hill Tracts, as well as poeticized and memorialized its lands and people through multiple literary, visual, and photographic methods. This book attempts to gauge the writings of these administrators on the hill region. But who exactly were they?

The Colonial Archive: Knowing and Classifying the Hills British political administrators, including scientists, topographers, explorers, and ethnologists,120 took up posts in ‘frontier’ regions such as the CHT, and in the process became would-be ethnographers of the peoples they encountered.

15 of 52