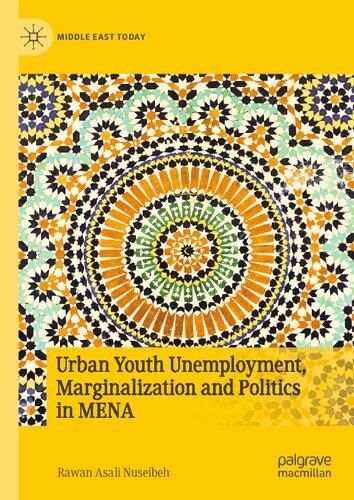

Americans in China

Encounters with the People’s Republic

LAUTZ

TERRY

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–751283–8

eISBN 978–0–19–263535–8

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197512838.001.0001

In memory of Douglas P Murray Friend, mentor, and advocate for understanding between the United States and China

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

A Chronology of US-China Relations

Introduction: A Tale of Two Chinas

I. FROM COLD WAR TO RECONCILIATION

1. Walter Judd: Cold War Crusader

2. Clarence Adams and Morris Wills: Searching for Utopia

3. Joan Hinton and Sid Engst: True Believers

4. Chen-ning Yang: Science and Patriotism

5. J. Stapleton Roy: The Art of Diplomacy

II. FROM COOPERATION TO COMPETITION

6. Jerome and Joan Cohen: Charting New Frontiers

7. Elizabeth Perry: Legacy of Protest

8. Shirley Young: Joint Ventures

9. John Kamm: Negotiating Human Rights

10. Melinda Liu: Reporting the China Story

Conclusion: The Search for Common Ground

Notes

Suggested Readings Index

Preface and Acknowledgments

In July 1960, I sailed across the Pacific Ocean from San Francisco to Taiwan with my parents and sister. After a calm and pleasant voyage, with a stop along the way in Japan, we disembarked at the port of Keelung on a hot, steamy day and drove for an hour to the capital city of Taipei where we would live for the next two years. I was nearly fourteen and it was my first encounter with anything Chinese.

The United States had diplomatic relations and a defense treaty with the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan, and my father, an Ordnance Corps Army officer, was assigned to the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG). Chiang Kai-shek, who had lost the civil war to the Communists a decade earlier, made speeches about recovering the mainland, but no one seemed to take his words seriously. While still under martial law, the island nation, some ninety miles off the Chinese mainland, was a poor, sleepy, peaceful backwater in those days.

That experience in Taiwan, where I attended Taipei American School, made me wonder about the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a land shrouded in mystery that we could only see from a hillside on the Hong Kong side of its border. It made me curious enough to pursue Chinese studies as an undergraduate at Harvard, one of the few US schools offering that option in those days. “That’s very interesting,” my mother said when I announced my major, “but what are you going to do with it?” She was asking a serious question because there were so few China-related jobs. I simply trusted that something would work out.

Yet it was only after college, after serving in Vietnam with the US Army, that my curiosity became more purposeful. The people of South Vietnam feared communism—many of them had escaped from the North—but their government’s alliance with the United

States undermined their claims to independence and nationalism. Reading Bernard Fall’s books about Ho Chi Minh’s defeat of the French in 1954 made it painfully clear that the United States, perceived as another colonial power, was repeating the same fatal mistakes. The tragic result of our leaders’ ignorance of Vietnam, a war fought as a proxy against China, was a wake-up call for me. Understanding our fraught history in Asia had become more than an abstract intellectual exercise.

My timing was fortunate. During my graduate school days at Stanford, US-China relations began to improve with the advent of ping-pong diplomacy and President Nixon’s historic trip to the People’s Republic. I returned to Taiwan—the mainland was still offlimits—for Chinese language study and research on a FulbrightHays Scholarship. After receiving a PhD in history, I landed a job in New York with the Asia Society’s China Council, a national public education program, led by Robert Oxnam, that connected with American scholars, journalists, businesspeople, and community leaders to provide balanced information on the PRC. Public interest was strong, but there was still a dearth of knowledge; we had yet, for instance, to realize the extent of devastation during the Cultural Revolution.

My first trip to mainland China, in December 1978, coincided with a major shift in the geopolitical landscape. I was escorting a small group of Americans, members of the National Committee on USChina Relations, on a three-week tour of several cities, starting in the north and ending in the south. On our final day, during a visit to the Huadong Commune on the outskirts of Guangzhou, I tuned in to Voice of America on my shortwave radio and listened to President Carter announcing that the PRC and the United States would establish full diplomatic relations. Our Chinese hosts were thrilled by the news and considerable toasting and drinking followed. Normalization, as it was called, ushered in a hopeful new era in Sino-American relations.

Now that the People’s Republic was opening up to Americans, I accepted an offer from the Yale-China Association, directed by John Starr, to represent its programs in Hong Kong and China. My wife Ellen and I arrived with our two young sons, Bryan and Colin, at New

Asia College at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) in the summer of 1981, our home base for the next three years. Everyone was concerned about Hong Kong’s transition from British control to Chinese sovereignty, scheduled for 1997, but with the Sino-British Joint Declaration signed in December 1984, Beijing reassured the world that it would be a smooth process. The city, while not a fullfledged democracy, had a strong legal and judicial system, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press—rights that were absent on the other side of the border. Under a policy of “one country, two systems,” Beijing would assume responsibility for foreign affairs and defense, but Hong Kong could maintain its own way of life as a special autonomous region for at least fifty years after the handover in 1997.

In addition to teaching and managing various projects at CUHK, I was responsible for overseeing Yale-China’s programs with Xiangya Medical School in Changsha and with Huazhong University and Wuhan University in Wuhan, relationships that had been restored after a thirty-year absence. On one occasion, some of the young Americans teaching English in Wuhan were accused of being spies. I quickly went there to meet with our Chinese colleagues, who soon put an end to the harassment. It was a distressing experience for the Yale-China teaching fellows and was a potent reminder that suspicion of the United States still ran deep. It also drove home the fact that the success of any American venture depended on having supportive Chinese partners.

In 1984, my family and I moved from Hong Kong to New York, where I joined the staff of the Henry Luce Foundation. Founded by Henry R. Luce, publisher of Time and Life magazines, who was born to missionary parents in China, it was chaired by his son Henry Luce III and led by Robert Armstrong. The foundation’s Asia program supported the creation of resources—language teaching, library materials, fellowships, faculty positions, policy studies, cooperative research, and cultural and scholarly exchange—to increase America’s capacity for understanding East and Southeast Asia. Much of my work centered on building cultural and scholarly ties between the United States and China. In addition to trips to the PRC, my travels also took me to Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, the

Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam, Japan, South Korea, and North Korea.

Of these journeys, the most unforgettable was a trip in the spring of 1989 to review some of the Luce Foundation’s grants. I flew from Hong Kong to Beijing on May 29 and after checking in to my hotel took a taxi to Tiananmen Square where thousands of students had been protesting against the Chinese government for weeks. Red banners with university names were stretched above their tents and, after finishing evening meals, they were lounging about playing cards, writing in their diaries, talking with passers-by A few of them asked me, “What do the people of America think about what we are doing?” “Are you allowed to have protests in America?” “Do you think we can succeed?”

Loudspeakers broadcast a steady stream of statements from the protest leaders, interspersed with music, including a new democracy song from Hong Kong. Food, drink, and popsicle vendors were doing a brisk business. I wrote in my journal, “Here and there are piles of discarded jackets and clothing for cooler weather, donated by the citizens of Beijing. There is a good deal of litter and occasional piles of garbage, but for the most part it looks like organized disorder. Visitors are taking photos of themselves in front of the tents and banners. The students seem terribly idealistic, committed, determined, and cheerful.”

Late that night, a thirty-foot “Goddess of Democracy” built by students at the Central Academy of Arts was brought to the square on four flat carts and plastered together on top of a wooden platform. After it was unveiled early the next morning, directly facing Mao’s giant portrait on the entrance to the Forbidden City, thousands of people flocked to Tiananmen to have a look. “You have your Statue of Liberty in America,” a man said to me, “and now we have ours here in China.” The government labeled it “an insult to socialism” and demanded that it be taken down. With a sense of foreboding, I left Beijing for a flight to Tokyo and Los Angeles on the morning of Saturday, June 3. That night, the non-violent protest movement was suppressed with brutal military force and the statue was toppled and destroyed.

I was disturbed, perplexed, and concerned about the future. Had young Chinese been misled into believing that American-style democracy could be accepted by a communist regime? What principles would guide US-China relations after the Tiananmen debacle, which China’s leaders blamed on the “black hand” of the United States? Were we destined to live through never-ending cycles of suspicion and distrust, or would it someday prove possible for Chinese and American interests and values to converge? The relationship between the United States and China has waxed and waned in the years since, but questions like these persist, questions that have led me to write this book.

I have long been interested in Americans whose firsthand encounters have informed and shaped our understanding of China, a number of whom have helped to make this book possible. First and foremost, I owe a great debt to those whose stories are told in the following chapters for allowing me to interview and quote them: Jerome Cohen, Joan Cohen, John Kamm, Melinda Liu, Elizabeth Perry, Stapleton Roy, and Shirley Young. It has been a privilege to write about each of them. (Other figures in the book have passed from the scene, and I was unable to meet with C. N. Yang.)

David McBride, my editor at Oxford University Press, first urged me to consider this project, and he and his team have expertly guided me through the publication process. I am also grateful to Mary Child, an independent editor of China studies, for her thoughtful advice and for gently but firmly pushing me to make my prose clear and strong. Sincere thanks friends who have read and commented on drafts of various chapters, including Mary Brown Bullock, Richard Bush, John Holden, Sophie Richardson, Douglas Spelman, and I am grateful to Jan Berris and David M. Lampton for reviewing the full manuscript.

Special appreciation is due to Molly Linhorst and Amanda Mikesell for their excellent research assistance, and to Anni Feng and Lingyu Fu for helping with translations and other parts of the book. I also express my appreciation to my students at Syracuse

University who helped me think through some of these biographies at an early stage of the project: Johanna Arnott, Gwendolyn Burke, Corey Driscoll, Dasha Foley, Michael Kosuth, Tanushri Majumdar, Liam McMonagle, Nicholas Miller, Lilibeth Wolfe, and Brianna Yates.

It is a great pleasure to acknowledge the generosity of many friends and colleagues who have shared their China experiences and offered advice through emails, phone calls, interviews, and conversations: William Alford, Halsey Beemer, Carroll Bogert, Mary Lou Carpenter, Lo-Yi Chan, Millie Chan, Frank Ching, Maryruth Coleman, Carl Crook, Elizabeth Economy, Bill Engst, Fred Engst, Jaime FlorCruz, Gao Yanli, Tom Gold, Lee Hamilton, Beverley Hooper, Nicholas Howson, Virginia Kamsky, Ambrose Y. C. King, Helena Kolenda, Mary Kay Magistad, Alfreda Murck, Christian Murck, Douglas Paal, Lynn Pascoe, Charles E. Perry, Steve Orlins, Nicholas Platt, Joshua Rosenzweig, Marni Rosner, Bill Russo, Rudy Schlais, Deborah Seiselmyer, David Shambaugh, Mark Sheldon, Robert Snow, Anne Keatley Solomon, Jane Su, Oscar Tang, Matt Tsien, Ezra Vogel, Genevieve Young, and Kenneth Young. My sincere thanks to Marni Rosner for giving me audio files of Neil Burton’s extensive conversations with Joan Hinton and Sid Engst.

I am grateful to Bloomsbury Academic for permission to quote from my chapter “Unstoppable Force Meets Immovable Object: Normalizing US-China Relations,” in United States Relations with China and Iran, Osamah F. Khalil, ed. (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019).

I also want to recognize the assistance of librarians and archivists at the following institutions: Andover Harvard Theological Library; Cornell University Archives; the Chinese University of Hong Kong (C. N. Yang Archives); Houghton Library and Pusey Library at Harvard University; Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University; University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library; George Washington University Archives; and Syracuse University Library.

Lastly, I offer my deepest gratitude and love to Ellen Stromberg Lautz, who has encouraged and sustained me at every step of the way.

A Chronology of US-China Relations1

1849–69 Chinese laborers are recruited to work in gold mines and to construct the transcontinental railroad in America’s West.

1872–81 The Chinese Educational Mission sends 120 Chinese young men to New England to study Western science and engineering

1882 The US Congress passes the Chinese Exclusion Act, which severely limits Chinese immigration to the United States

1900 Eight nations, including the United States, suppress the anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion The United States uses some of the indemnity money for fellowships to educate Chinese in the United States

1911–12 Sun Yat-sen establishes the Nationalist (Kuomintang) Party after the collapse of the Qing dynasty and founds the Republic of China.

1916–22 The New Culture Movement attacks Confucianism and traditional society as the source of China’s weakness.

1919 The May Fourth Movement, sparked by the treatment of China in the Treaty of Versailles, marks the birth of modern Chinese nationalism.

1921 The Chinese Communist Party is established in Shanghai.

1925 Chiang Kai-shek succeeds the late Sun Yat-sen as leader of the Nationalist government. Chiang agrees to become a Christian when he marries US-educated Soong Mei-ling in 1927.

1928 China is unified under a single government led by the Nationalists

1930s The high-tide of American missionary efforts to provide medical training, relief work, and Western-style liberal arts education in China

1931 Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth, a sympathetic novel about the lives of Chinese peasants, is a major bestseller in the United States

1941–45 During World War II, the United States allies with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and cooperates with Mao Zedong’s Communists against Japan. US support is limited to air power.

1943 The 1882 Exclusion Act is repealed, but restrictions on Chinese and Asian immigration to the United States remain in place until the Immigration Reform Act of 1965.

1945 Japan surrenders after atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

1945–49 During the Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists and Communists, the United States gives military and economic aid to the Nationalists despite concerns about widespread corruption and incompetence.

1949 Founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), led by Mao Zedong, chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) The Truman administration is charged with the “loss of China ” Some ten thousand Chinese students and professionals who are not US citizens are stranded in the United States Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government retreats to the island of Taiwan (Formosa) Beijing claims Taiwan as part of China, but the United States continues to recognize the Republic of China (ROC) as China’s legitimate government.

1950–53 The United States and PRC are the primary combatants during the Korean War, which ends in a stalemate and a divided Korean peninsula. Twenty-one captured American soldiers decide to go to China instead of returning to the United States, and thousands of Chinese POWs go to Taiwan American missionaries and businessmen are forced to leave China; only a small number of Westerners are allowed to stay

1950–71 US containment policy prohibits any trade or travel between the two countries The United States successfully opposes the PRC’s admission to the United Nations

1954–55 The First Taiwan Strait Crisis over PRC attacks on islands along China’s mainland held by the Nationalists. The United States and Taiwan agree to a Mutual Defense Treaty.

1955–70 US–PRC ambassadorial talks in Geneva and Warsaw, a series of 136 meetings, in the absence of diplomatic relations.

1957 A group of forty-one young Americans visit the PRC for six weeks, despite a US State Department ban on travel to Red China.

1958 The People’s Liberation Army bombards offshore islands controlled by Nationalist forces during the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis.

1958 Mao launches the Great Leap Forward to rapidly industrialize the PRC’s agrarian economy

1959–61 An estimated thirty million people die during the Great Chinese Famine

1964 The PRC successfully tests a nuclear bomb

1966 The National Committee on US-China Relations is established to promote discussion about reconsidering Washington’s containment policy The Committee on Scholarly Communication with the PRC (CSCPRC) is founded to sponsor short-term academic exchanges, mainly in the sciences.

1966–76 The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, Mao’s bid to reassert his control over the CCP, leads to massive social, economic, and political turmoil and bloodshed.

1971 American ping-pong players visit China, the first sign of a thaw between Beijing and Washington. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger secretly visits Beijing to lay the groundwork for President Nixon’s trip to China. The PRC is admitted to the United Nations and the ROC (Taiwan) is forced to withdraw

1972 President Richard Nixon meets Mao and Zhou Enlai and signs the Shanghai Communiqué acknowledging that Taiwan and China agree there is only one China

1976 Death of Mao Zedong and arrest of the Gang of Four, who are blamed for the Cultural Revolution

1977 The National Association of Chinese Americans (NACA) advocates for diplomatic relations between Washington and Beijing.

1978 Deng Xiaoping launches the era of Reform and Opening to modernize China. Wei Jingsheng posts a manifesto on Democracy Wall in Beijing calling democracy “the fifth modernization ”

1979 Washington establishes full diplomatic relations with Beijing and breaks diplomatic relations with the ROC on Taiwan Deng Xiaoping visits the United States for talks with President Carter The US Congress passes the Taiwan Relations Act to maintain unofficial relations with Taiwan

1980 The United States and China sign a trade agreement Business, scholarly and cultural exchanges expand, and American news organizations establish bureaus in Beijing. China joins the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

1982 The Reagan administration signs a third joint communiqué with the PRC, stating that the United States “intends to reduce gradually the sales of arms to Taiwan.”

1983–84 Deng Xiaoping announces the “one country, two systems” policy to reassure the people of Hong Kong and Taiwan that they will retain considerable autonomy after reunification with the PRC.

1983–84 The CCP promotes a campaign against “spiritual pollution” to limit Western influence.

1987 The Anti-Bourgeois Liberalization Campaign demonstrates renewed conservative Chinese concern over imported Western values Martial law is lifted and Taiwan becomes a constitutional democracy

1989 Pro-democracy protests take place in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square and other cities in China The People’s Liberation Army brutally ends the movement on June 4 The Bush administration imposes economic and military sanctions in response The Committee of 100 is established in New York City to advance US-China Relations and to advocate for the rights of Chinese Americans.

1990 President H. W. Bush signs an executive order allowing as many as forty thousand Chinese students to stay in the United States. Dissident Fang Lizhi is allowed to leave for the United States after taking refuge in the US embassy for a year.

1992 Deng Xiaoping’s “Southern Tour” of China signals the resumption of economic reforms that had been paused after the 1989 Tiananmen crisis.

1993 The United States claims that the Chinese ship Yinhe is carrying chemical weapon materials to Iran The ship is boarded and no evidence is found

1994 President Clinton’s administration ends its policy linking Most Favored Nation (MFN) status for China with its progress on human rights

1995–96 Taiwan’s President Lee Teng-hui visits Cornell University despite PRC protests During the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis, Beijing fires missiles into Taiwan’s territorial waters to warn the ROC government against independence The United States deploys two carrier battle groups to the western Pacific in response.

1997–

98 Presidents Jiang Zemin and Bill Clinton hold meetings in Washington and Beijing, the first summits since 1989.

1997 The British colony of Hong Kong is returned to Chinese sovereignty Beijing promises that Hong Kong can retain its own system for fifty years

1999 Taiwanese American scientist Wen Ho Lee is accused of giving classified information to the PRC, but the case against him is not proved A US plane bombs China’s embassy in Belgrade, Kosovo, killing three Chinese citizens Refusing to believe it was an accident, Chinese citizens take to the streets to demonstrate in major cities The Portuguese colony of Macao is returned to Chinese sovereignty.

2001 A US spy plane and PRC fighter jet collide over the South China Sea. The Chinese pilot is killed and the US crew is held for ten days on Hainan Island. The PRC is admitted to the World Trade Organization (WTO) with US backing, which provides a major boost to its economy.

2003 President George W. Bush warns Taiwan President Chen Shui-bian against seeking independence.

2008 President Bush attends the Beijing Summer Olympics despite protests over repression in Tibet.

2010 China surpasses Japan as the world’s second-largest economy. Dissident Liu Xiaobo receives the Nobel Peace Prize but cannot accept in person because he is in prison in China

2011 The United States announces a “pivot” to Asia to counter China’s growing power

2012–

13 Xi Jinping is elected general secretary of the CCP and president of the PRC He consolidates his power and warns against the dangers of Western values President Obama and Xi Jinping meet at the Sunnylands estate in California to discuss climate change, cybersecurity, US arms sales to Taiwan, North Korea’s nuclear program, and other issues.

2015 The United States warns China against building military outposts on islands in the South China Sea.

2017 President Trump hosts Xi Jinping in Florida for discussions on North Korea and trade in April. Trump makes a state visit to China.

2018 The Trump administration imposes substantial tariffs on China for the alleged theft of intellectual property and other unfair trade practices. China responds with its own tariffs on US goods.

2019 Uyghur Muslims are detained in mass internment camps in Xinjiang The US Congress passes the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which mandates an annual review of Hong Kong’s autonomy to justify its special trading status with the United States

2020 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) erupts in Wuhan, disrupting global trade and travel and initiating a downward spiral in US-China relations China passes a National Security Law to crack down on pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. President Trump signs an executive order ending Hong

Kong’s preferential trade status. The United States withdraws the Peace Corps from China and shuts down the PRC consulate in Houston based on charges of spying China closes the US consulate in Chengdu in retaliation Both countries impose restrictions on journalists Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declares that the era of engagement with the Chinese Communist Party is over Fears of a new Cold War between the United States and China increase

Introduction

A Tale of Two Chinas

In the summer of 1957, the Chinese government invited a group of young Americans who were attending a World Youth Festival in Moscow to visit the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The US State Department sternly warned them against accepting. If they did so, their passports—stamped “not valid for travel to those portions of China, Korea, and Viet-Nam under Communist control”—would be revoked, fines could be imposed, and they might be liable to prosecution. (No such restrictions applied to the Soviet Union, which established diplomatic relations with the United States in 1933.) President Eisenhower called the potential trip “ill-advised.” If they made the journey, said Under Secretary of State Christian Herter, they would be “willing tools” of the Chinese Communists.1

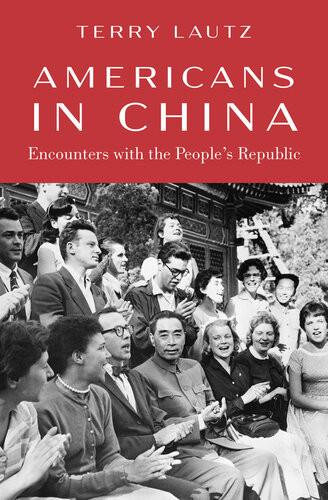

Several decided against going to the PRC, but forty-one, most of them students, were willing to defy the US government. The Chinese embassy issued visas on separate pieces of paper so their passports would have no evidence of their having been in Red China. The New York Times reported that “a brass band blared and a thousand flower-bearing Russians waved” as the exuberant group set off on the Trans-Siberian Express from Moscow Yaroslavsky station.2

A wildly enthusiastic crowd of young Chinese greeted the delegation when they arrived one week later at the Peking Railway Station on August 23. “As soon as they stepped on the forbidden land,” wrote a Reuters correspondent, “they were surrounded by hand-shaking, clapping, back-slapping Chinese who pressed flowers into their hands.” The cheering redoubled when one of the Americans unfurled a large Stars and Stripes flag which the Russians had made for the Youth Festival. The Chinese began singing “John Brown’s Body” and everyone joined in chanting “Long

Live World Peace.” From their hotel a short while later, the Americans issued a statement that they regarded the visit as “an important step toward free interchange between China and the United States.” They wanted not only to learn about contemporary China but also hoped to “give the Chinese people some understanding our own country.”3 The official People’s Daily carried a front-page story celebrating their visit.

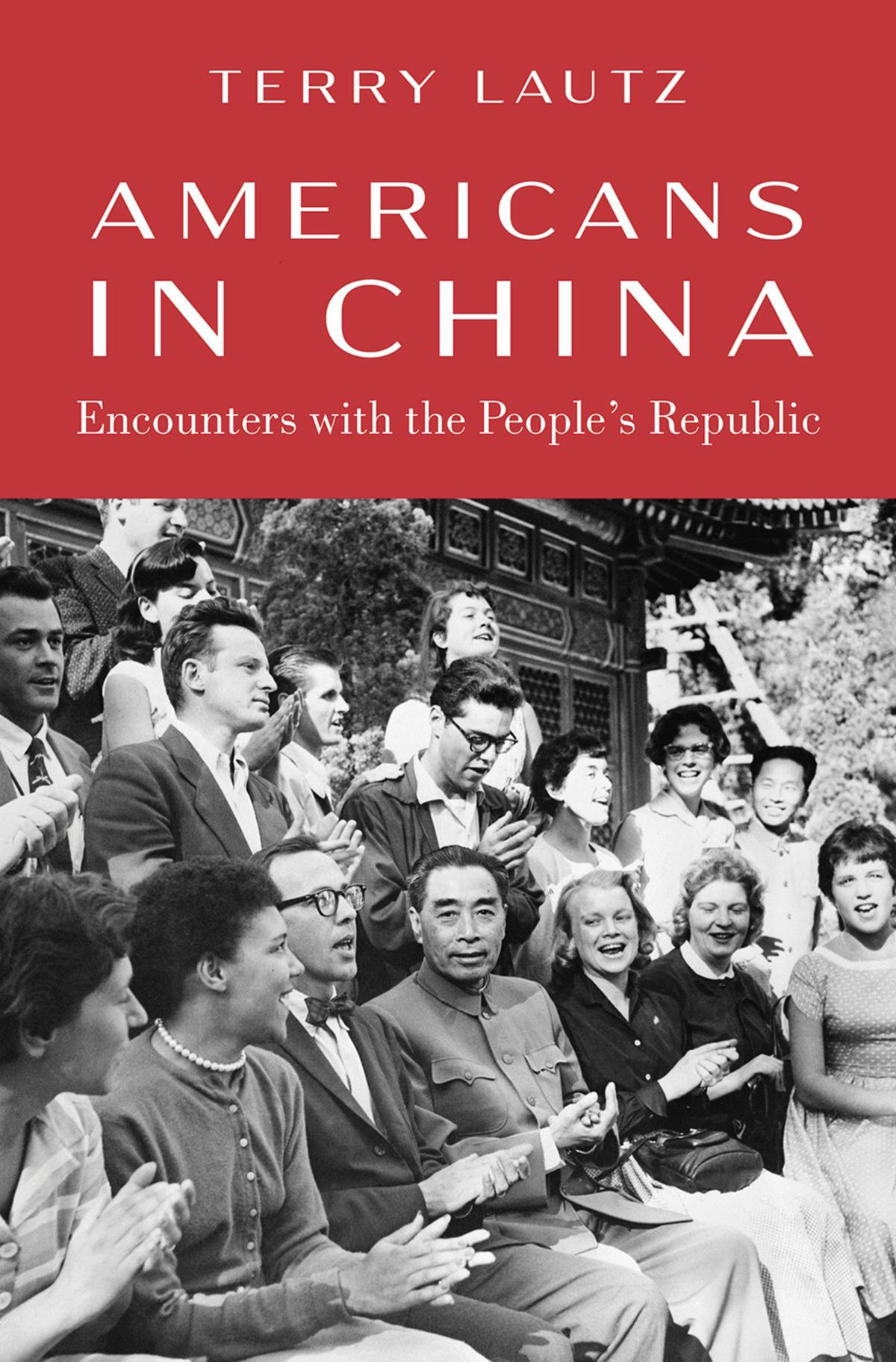

Chinese students welcoming an American youth group arriving from Moscow at the Peking Railway Station, August 1957

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images.

As guests of the All-China Federation for Democratic Youth, which covered all expenses for the trip, the group toured eight cities over a period of six weeks. During their visit to Changchun, an industrial city in the northeast, they demonstrated basketball, jitterbugging, and

truck driving. They attended the October 1 National Day parade in Beijing and met with Premier and Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai who agreed with the visitors that achieving world peace and improved US-China relations would depend on not only the efforts of professional diplomats but also direct communication between citizens of the two countries.4

Because the US government prevented American news organizations from sending their own journalists to cover the story, the Associated Press, United Press International, and NBC enlisted members of the delegation as special correspondents.5 NBC gave a movie camera to Robert C. Cohen, who had studied film at UCLA, asking him to document their visits to schools, hospitals, factories, and a Peking Opera performance. “China may be changing, but it is still a land of great contrasts,” narrated Cohen in the film he made after the trip. He was impressed by the PRC’s progress in eliminating epidemics and diseases, but tuberculosis was still widespread. The construction of locomotives, bridges, and ships showed China’s rapid industrialization, but the use of “primitive” manual labor instead of machines was commonplace. The country was largely selfsufficient, but Russian technicians worked at some sites. The government paid for and controlled university education, but between eight and ten students were “crammed” into small dormitory rooms. There were a small number of Chinese Christians, but foreign missionaries were banned.6

Most of the stories that generated headlines back in the United States, however, did not depict everyday Chinese life; instead they were blunt reminders that the two nations remained Cold War foes. On one occasion, several members of the group were taken to a prison in Beijing where they spoke with John Downey and Richard Fecteau, CIA agents whose plane was shot down on Chinese territory in 1952. In Shanghai, others met with Hugh Redmond, an American businessman serving a life sentence, also accused of working for the CIA, as well as two US Catholic priests, Joseph McCormick and John Wagner, who were being held as prisoners. A more upbeat conversation was arranged with Morris Wills (whose story is told in Chapter 2), a US Korean War veteran who chose to

live in China and was studying Chinese language and literature at Peking University.7

In retrospect, the unprecedented 1957 trip was not, as the young Americans had hoped, “an important step toward free interchange between China and the United States.” Fourteen members of the group who flew back to Moscow said they were glad they had made the trip, but were told by a US Embassy official that they had violated US regulations, and their passports would be stamped as good only for the return trip to the United States.8 Needless to say there was no reciprocal invitation for Chinese students to visit the United States. The gulf between the two nations simply was too wide and deep, and the unexpected encounter was soon forgotten, leaving barely a trace in the annals of Sino-American history.

What a world of difference fourteen years later when an American ping-pong team received a sudden invitation to visit China in April 1971. This time, the US government, which had ended its ban on travel to Communist China one month earlier, welcomed Beijing’s initiative. The US athletes, who were competing in the World Table Tennis Championship in Nagoya, Japan, flew to Hong Kong and crossed the PRC border from there. In contrast to the 1957 trip, professional journalists representing NBC, the Associated Press, and Life magazine were allowed to accompany them. This time, the American public treated the sports delegation as celebrities, and Chinese and Americans alike were captivated by the antics of Glenn Cowan, a long-haired hippie who wore a floppy yellow hat. (Various publications mistakenly reported they were the first group of Americans to enter China since the Communist takeover in 1949.)

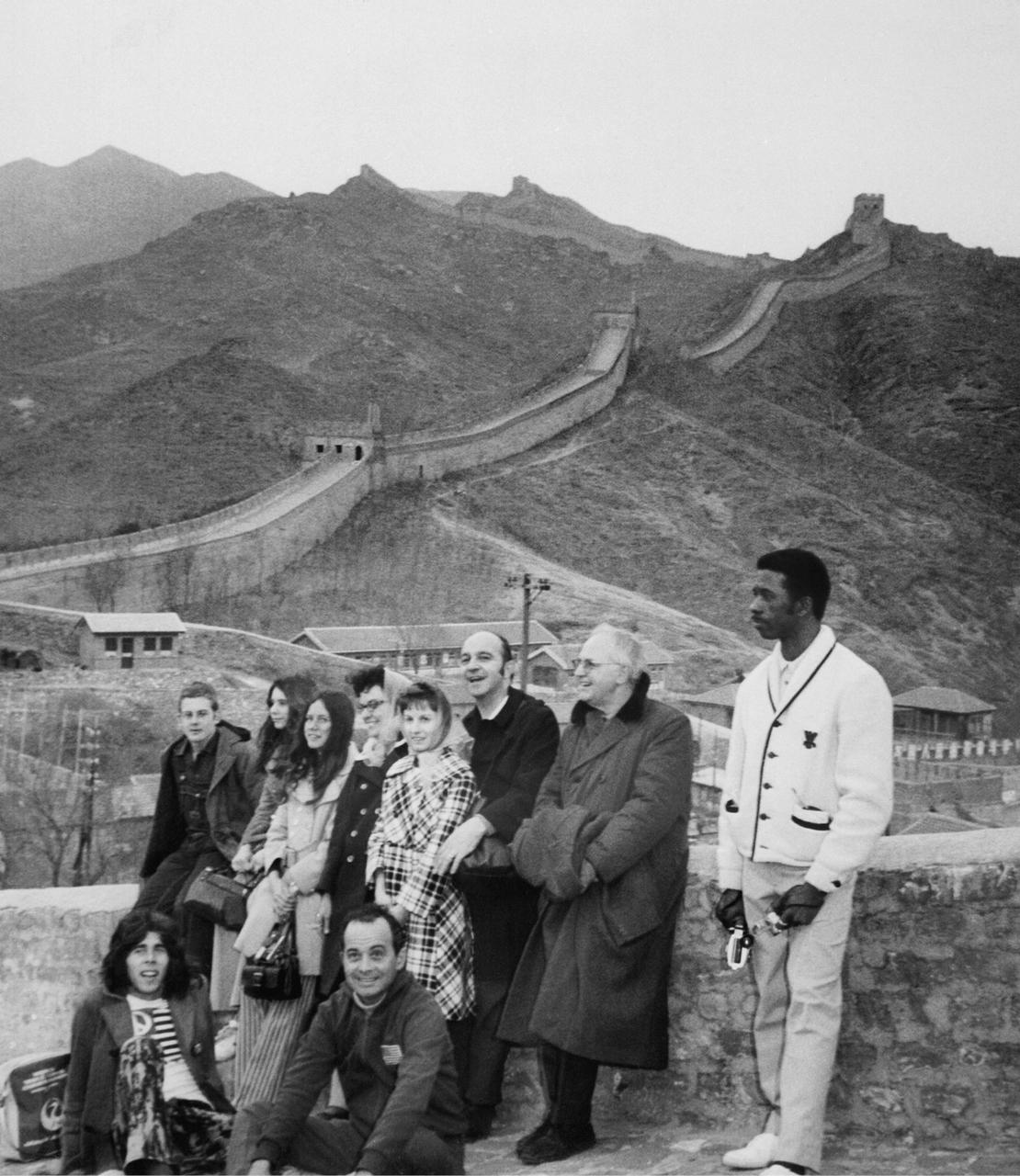

American ping-pong players on Great Wall, April 1971. STAFF/AFP via Getty Images.

The ping-pong delegation represented a sensational unofficial opening that permitted the two governments to sidestep divisive policy issues. Nine players, four officials, and two family members

toured Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing; their visit to the Great Wall was featured on the cover of Time with a banner “Yanks in Peking” and the headline “China: A Whole New Game.” Exhibition matches were played under the slogan “Friendship First and Competition Second,” which was fortunate because the Chinese players were the best in the world. China’s ambivalence about the United States was nonetheless in evidence: a sign in one stadium read “Welcome to the American Team” while another said, “Down with Yankee Oppressors and Their Running Dogs.” Zhou Enlai received the Americans at the Great Hall of the People, along with table tennis teams from several other countries, and congratulated them on opening “a new chapter in the relations of the American and Chinese people.” On the same day, President Nixon announced that the United States was lifting its twenty-year-old trade embargo on Communist China.

Twelve months later, China’s ping-pong team arrived in the United States for a tour of eight cities, cosponsored by the US Table Tennis Association and the National Committee on United States-China Relations, both private organizations. Cultural differences sometimes puzzled the Chinese players, and politics occasionally intervened. During their initial match in Cobo Hall in Detroit, an anti-communist group dropped white paper parachutes with dead mice from a balcony onto the arena below. Small pro-Taiwan groups showed up at other venues shouting, “Down with the Communists” and “The Republic of China is Free China.” Nixon received the Chinese team in a Rose Garden reception at the White House, but they refused to tour the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts because both the ROC (Republic of China) and PRC flags were displayed there.9 But on the whole, Jan Berris, a National Committee staff member who traveled with the team, remembers the large crowds of people at the matches as being enormously curious and expressing “a huge amount of warmth and friendliness” toward the Chinese.

Despite a few disruptions, the 1971–72 exchange of table tennis teams was deemed a major success, in stark contrast to the unauthorized 1957 tour that had barely registered on America’s consciousness. Ping-pong diplomacy signaled that the United States and China were ready to reevaluate their adversarial relationship.

President Nixon said there would be winners and losers in the matches, but “the big winner will be the friendship between the people of the United States and the people of the People’s Republic of China.”10 The interchange of individual Americans and Chinese had paved the way for a much bigger game.

Misunderstanding China

Neither in 1957 nor in 1971 did the Americans who visited China have any idea of what to expect. Most knew little beyond popular stereotypes of the day: the diabolical Dr. Fu Manchu, the clever detective Charlie Chan, the peasants of Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth, and the adventures of comic strip characters in Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates. Chinese Americans, few in number and concentrated mainly in San Francisco and New York Chinatowns, were the subject of curiosity, suspicion, and disdain. China was mysterious and captivating, fearful and foreboding. A jumble of contradictory images oscillated between admiration and contempt, brilliantly documented in Harold Isaacs’ book Scratches on Our Minds and Irv Drasnin’s film Misunderstanding China. 11

Beyond such clichés, there was a more serious, equally persistent, liberal dream for China, rooted in the Christian missionary movement, which had given birth to the belief that the United States had an obligation to share its version of prosperity with the rest of the world. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, China was by far the most exciting and compelling destination for American missionaries, including a sizable number of single women who had few opportunities for professional employment beyond teaching and nursing. They went not only to share the Gospel but also to build schools and hospitals and to provide social services and relief work as expressions of their faith. During sabbaticals back home, they visited churches and college campuses where they showed lantern slides and talked about China’s great need for help. They embodied the idea that the United States had a moral responsibility to aid China in becoming a progressive society in its own image. This well-meaning, paternalistic vision, which assumed

the superiority of Western values, gave rise to a relationship that was unusually emotional and sentimental.

The lure of China as a potentially vast market for business was another aspect of America’s ambition to remake the Middle Kingdom. The application of Western-style management and advertising was the key to success for companies like British American Tobacco, the Singer Sewing Machine Company, and John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, under the slogan “Oil for the Lamps of China.” Other firms pioneered modern business practices for newspapers, banking, and insurance. Like the missionaries—who never converted more than a very small percentage of the Chinese population—total US trade and investment in China was modest. Nevertheless, the free enterprise model left its mark and added to the idea of China’s becoming “just like us.”

With the advent of Communist rule in 1949, the American dream for China was extinguished—at least for the time being. Prior to the Communist revolution, missionaries and businessmen tried to persuade the Chinese that Christianity and capitalism offered the path to a strong, prosperous, just society. Rejecting these interlopers as agents of “cultural imperialism,” the Communists preached a radical faith that cast the West in general and the United States in particular as the enemy. The Chinese Communist Party blamed outsiders for a “century of humiliation.”

As historian Jonathan Spence has written, China had “regained the right, precious to all great nations, of defining her own values and dreaming her own dreams without alien interference. China’s leaders could now formulate their own definition of man, restructure their own society, pursue their own foreign policy goals.”12 Except for a handful of Western sympathizers and thousands of Russian advisers, anyone who did not hold a Chinese passport either chose to leave the PRC or was forced to do so.13 A number of foreigners, notably Catholic nuns and priests, were imprisoned. China was no longer a feeble victim that looked to other countries for deliverance, but a unified nation with a singular purpose.

The American public responded to the so-called “loss of China” with a mixture of anger, confusion, and regret when the longstanding ambition to save a poor, benighted China disappeared with