1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Alborn, Timothy L., 1964– author.

Title: All that glittered : Britain’s most precious metal from Adam Smith to the Gold Rush / Timothy Alborn.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: LCCN 2019005620 (print) | LCCN 2019008847 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190603526 (updf) | ISBN 9780190603533 (epub) | ISBN 9780190603519 (hardcover : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Gold—Great Britain—History. | Gold standard—Great Britain—History. | Finance—Great Britain—History. Classification: LCC HG295. G7 (ebook) | LCC HG295. G7 A43 2019 (print) | DDC 332.4/0420941—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019005620

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

Acknowledgments vii

Introduction 1 Gold between Tradition and Modernity

1. Domestication 12

2. Value 28

3. War 47

4. Trade 65

5. Coinages 79

6. Distinction 96

7. Display 113

8. Devotion 130

9. Graven Images 146

10. Before the Gold Rush 161

Conclusion 177 Gold Rushes

Notes 197 Selected Bibliography 241 Index 251

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Although I have been working in earnest on this book since 2009, its genesis dates back to graduate school in the late 1980s, when I first confronted the strangeness of the gold standard. I thank my dissertation advisers, Barbara Rosenkrantz and Peter Buck, for encouraging me to “think outside the box” about gold and other matters back then; and Peter has generously continued to read in manuscript almost everything I write, including All That Glittered. Over the nearly thirty years since my Ph.D. I have developed my ideas about gold whenever I have taught British history, first at Harvard and, since 1998, at Lehman College and the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center: thanks go to the many students who probably did not anticipate learning so much about that metal when they signed up for my classes.

My colleagues at Lehman and the Graduate Center have provided a friendly and intellectually stimulating environment for thinking, talking, and writing about history. At Lehman, Evelyn Ackerman, Cindy Lobel, José Luis Renique, Robyn Spencer, Chuck Wooldridge, and Amanda Wunder all provided sounding boards for ideas that made it into the book, as have Laird Bergad, Sarah Covington, Josh Freeman, Jim Oakes, Helena Rosenblatt, David Troyansky, and Randy Trumbach at the Graduate Center (special thanks to Amanda and Sarah for reading draft chapters). Laura Guerrero at Lehman and Marilyn Weber at the Graduate Center have also been amazing resources. Between 2009 and 2012, when I began working on this book while serving as Dean of Arts and Humanities at Lehman, my colleagues and staff in Shuster Hall understood that my love of research enhanced rather than impeded my administrative duties.

All That Glittered is the result of an enormous amount of work, not all of it mine. CUNY has blessed me with an abundance of funds for research assistance, and I have been lucky to be able to employ a talented group of Ph.D. students over the years. Sam Bussan, Igor Draskovich, Jiwon Han, Andrew Kotick, Esther Mansdorf, Sophie Muller, Matt Sherman, Mark Soriano, Jaja Tantirungkij,

and Ky Woltering have all left their mark on this book through their tireless downloading and organization of PDF files, compilation of databases, scanning of books, checking of quotes, and tracking down of illustrations. My doctoral students Dory Agazarian, Alex Baltovski, Phelim Dolan, Jarrett Moran, and Luke Reynolds (as well as Sophie, Jaja, and Jiwon) have also read chapter drafts and generally put up with my penchant for talking incessantly about my research.

The staff of the National Archives in London, as well as Justin CavernelisFrost at the Rothschild Archive, Eve Watson at the RSA Archives, Alex Ritchie and Richard Wiltshire at the London Metropolitan Archives, and Joe Hewson and Margherita Orlando at the Bank of England Archives, all provided important assistance with my research. All That Glittered has also gained immensely from the interlibrary loan heroes at Lehman (Gene Laper) and the CUNY Graduate Center (Silvia Cho and her staff). Finally, it would have not been possible to write this book without access to electronic collections of primary sources. I’m especially grateful to Ray Abruzzi, Scott Dawson, and Theresa DeBenedictis at Gale and to Janet Munch and Stefanie Havelka at Lehman, who have provided access to many of these; and to the dozens of anonymous librarians around the world who scanned and coded the thousands of digital resources I consulted.

I have also gained from the community of literary critics and historians in the New York area, who have provided fertile soil for writing and thinking about All That Glittered. My Victorianist writing group—Tanya Agathocleous, Carolyn Berman, Deborah Lutz, Caroline Reitz, Talia Schaffer, and Marion Thain— provided lasting friendship and constructive feedback on several chapters and related articles over many tasty meals. For most of the time while I was working on this book I also had the privilege of discussing new books in British history over wine and cheese with Chris Brown, Evan Haefeli, Guy Ortolano, Susan Pederson, George Robb, Deborah Valenze, Kathleen Wilson, Rebecca Woods, and Alex Zevin. In and beyond New York, I have also been given opportunities to discuss my work at various workshops and seminars. For these I thank Joe Childers (The Global Nineteenth Century, Riverside), Catherine Delyfer (Gold in/and Art, Toulouse), David Lerer (European History and Politics, Columbia), Patrick Scott (Victorian Disruptions, Columbia, SC), David Weiman (Economic History Seminar, Columbia), and Carl Wennerlind (Mercantilism through the Ages and The Social, Legal, and Political Life of Money, both at Columbia). I also express appreciation to the Schoff Fund at the University Seminars at Columbia University for their help in publication. Material in this work was presented to the University Seminar: Modern British History.

In addition to these interactions, Brian Cooper, Alex Dick, Adrienne Munich, Maura O’Connor, and Carl Wennerlind have taken the time to comment on specific chapters. Many other friends and colleagues have inspired me with their conversations: these include Jenny Anderson, David Blaazer, Stephanie Burt,

Deborah Cohen, Martin Daunton, Will Deringer, Chris Desan, Jonathan Eacott, Doucet Fischer, Paul Gillingham, David Goodman, Jeannette Graulau, Anne Humpherys, Joe Kelly, Dane Kennedy, John Kleeberg, Seth Koven, Ayla Lepine, Paula Loscocco, Sharon Murphy, Paul Naish, Tillman Nechtman, Prasannan Parthasarathi, Richard Price, Erika Rappaport, Phil Stern, and Rebecca Spang.

Portions of this book have previously appeared in the Journal of the History of Ideas and the Journal of Victorian Culture; I wish to thank Martin Burke and Alastair Owen, and the anonymous referees of both journals, for their valuable feedback on those articles. Martin Hewitt, who asked me to write an entry on money in The Victorian World, enabled me to try on for size several ideas that made it into the book. Art Resource, British History Online, the British Museum, Columbia University Libraries, the Morgan Library and Museum, the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (Sydney), the Museum of the History of Science (Oxford), the National Portrait Gallery, the New York Public Library (General Research Division), the Royal Collection Trust, the Tate Gallery, and the Victoria and Albert Museum all provided valuable assistance in obtaining permission for and providing images used in this book. Last but not least, Susan Ferber has been very helpful at Oxford University Press at shepherding the book from proposal to proofs, as have been the referees of the proposal and book manuscript.

A silver lining throughout the arduous process of balancing All That Glittered with a full plate of teaching and administrative duties has been the unwavering support of my wife, Alix Cooper, and the constant companionship of our cat Hermione. Alix’s persisting love and trust has meant the world to me in sustaining belief in myself and in this project.

All That Glittered

Introduction

Gold between Tradition and Modernity

From the early eighteenth century into the 1830s, Great Britain was the only major country in the world to adopt gold as the sole basis of its currency, in the process absorbing much of the world’s supply of that metal into its pockets, cupboards, and coffers.1 During the same period, Britons “forged a nation” by distilling a heady brew of Protestantism, commerce, and military might, while preserving important features of its older social hierarchy.2 All That Glittered argues for a close connection between these occurrences, by linking justifications for gold’s role in British society—starting in the 1750s and running through the mid-nineteenth century gold rushes in California and Australia—to contemporary descriptions of that metal’s varied values at home and abroad. Most of these accounts attributed British commercial and military success to a credit economy pinned on gold, stigmatized southern European and subaltern peoples for their nonmonetary uses of gold, or tried to marginalize people at home for similar forms of alleged misconduct. This book tells a primarily cultural origin story about the gold standard’s emergence after 1850 as an international monetary system, while providing a new window on British exceptionalism during the previous century.

The conjunction of gold with British national identity emerged as a result of shifts in global trade and new monetary policies. In the course of its expanding commerce with Asia during the seventeenth century, the East India Company drained Britain of much of its silver coin; trade with France in the early eighteenth century replaced that silver with gold. As Master of the Mint, Isaac Newton adjusted to these developments by fixing the official value of the gold guinea at twenty-one shillings, which had the effect of driving out even more silver and establishing gold as the reigning currency.3 Trade within Britain had reached the point where larger transactions could be settled with guineas, and the majority of the population who needed smaller sums made do with token coins, copper pence, and whatever silver shillings remained in circulation.4 Through the 1750s,

when gold production boomed in Brazil, Britain’s favorable trade balance with Portugal enabled a sufficient influx of gold to sustain what had become a de facto gold standard.

For a gold standard to work, de facto or otherwise, it is necessary for credit to allow a little gold to go a long way. A gold (or silver) standard works when banks promise depositors to exchange the paper money they issue as loans for metallic currency on demand. Trust that they will do so enables these banks to circulate far more notes than the gold they hold in reserve. Britain was even more advanced in this regard than the Netherlands, from which it learned many of its financial tricks. Following its establishment in 1694, the Bank of England soon evolved into a lender of last resort: its gold backed not only its own paper, but the notes issued by dozens of private banks as well, including a cluster of large and stable joint-stock banks in Scotland.5 In addition to the gold held by the Bank, an equal quantity circulated as coin, while even more adorned Britons’ bodies and houses; the result, according to one pamphlet from 1760, was that “Gold, which during half an Age had never changed its abode,” now “shifted with such wonderous Quickness . . . that the Eye follows it in vain.”6

Besides being in the forefront of commercial credit, Britain also led the way during the eighteenth century in creating and sustaining an intellectual justification for a credit economy based on gold. This was part of a more general theory of social progress, which posited that human societies advanced from hunting and gathering, through tending livestock, then farming, then finally a fully commercial economy with all the advantages bestowed by the division of labor. Although French philosophes produced similar theories after 1750, it was the British version (first developed by Lord Kames, then perfected in the 1760s by Adam Smith) that found special application to the problem of money. As historian Craig Muldrew has argued, such stories about social development enabled Britons to make sense of money and credit as forms of “cultural currency” that transcended the intrinsic worth of gold and silver, while extending the division of labor to commercial exchange: precious metals “existed as the ultimate means of payment within credit networks,” but only “in specified areas and transactions.”7

This was the monetary and intellectual context for Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776), which provided much of the language by which Britain refashioned itself as an economic power. According to Smith, people initially valued gold for its beautiful appearance; its scarcity soon conferred status on those who were able to sacrifice means of subsistence to obtain it. Once these properties had endowed gold with sufficient value, the state took advantage of its additional qualities—ductility and fusibility—to press it and guarantee its weight with an official stamp. This final validation of gold’s cultural currency rescued would-be merchants from the inefficiencies of barter, paving the way for

commercial farming and industry—and also for international trade, where gold (as well as silver) served the additional function of balancing foreign payments. Having safely lodged gold in the Bank of England, Smith devoted the rest of his discussion of money to the complex machinations of credit. Secure in the assumption that gold would never be in short supply in Britain (thanks mainly to its advanced credit economy), he took an agnostic stance regarding its persistent ornamental uses.8

Subsequent Britons echoed Smith’s account of gold’s place in the evolution of money, but increasingly condemned ornamental gold. The political context for their new aversion to adornment was the drain of bullion occasioned by an enduring war against France (1793–1815), which led many to conclude that gold needed to be reserved for its most “civilized” function of all—as a foundation, in the form of coin and bullion, of Britain’s proliferating supply of bank notes and bills of exchange. As a result, the “beauty” phase of Smith’s speculative history of gold came to connote cultural inferiority, reinforced by British travel accounts of Southern European, Asian, and African men and women wearing the metal as jewelry and Italian, Russian, and Mexican cathedrals adorned with gilded saints. Meanwhile, novels, plays, and local histories quarantined gold in Britain’s recent past, where aristocratic dandies had sported chains, canes, buckles, and lace that pointed to that metal’s transitional role as a signifier of status.

Smith’s conjectural history of gold and its later modifications hewed closely to Max Weber’s twin categories of “market situation” (class) and “style of life” (status), which molded the changing contours of British politics and culture during the decades on either side of 1800. By definition, what was precious could not be possessed equally: in this sense gold set Britain apart from the rest of the world, but also set some Britons apart from others. How it did this was always complicated. As money, gold persisted throughout much of the eighteenth century as a stand-in for “market situation.” Even after 1820, when gold coins mainly circulated among shopkeepers and better-off laborers, the notes and bills held by their social superiors owed their value to the vast gold supplies at the Bank of England. By the 1780s, decorative gold had passed from being a nearly exclusive marker of an aristocratic “style of life” to being relegated to the ranks of the nouveau riche, and new laws and technologies made gold or difficult-todetect imitations accessible to nearly all social ranks after 1820. These changing functions of gold roughly reflected the arc of the British aristocracy, which established a fortuitous hegemony of both economic and social power between 1780 and 1830 before embarking on a decades-long decline.9

Gold’s dual role in this history of class and status provides a strikingly useful map for exploring Britain’s ascendance during the century after 1750. Specifically, its peculiar status as both a marker of value and a valuable commodity closely mirrored a social structure that balanced dynamic economic and social forces

against traditional hierarchies. The dominant British discourse on gold, which privileged its use as currency over decoration, aligns with an interpretation of that century as radically modern, whereby Britain took a comfortable if short-lived lead in the race among nations for wealth and power. According to this account, Britain’s subordination of ornament to currency accompanied a Promethean accumulation of property, ample expenditure on a “fiscal military state,” and imperial expansion. This side of gold also aligns with a similarly modernizing story, pioneered by Weber, of the rise of the Protestant ethic as a cultural precondition for capitalism. By this logic, in transporting gold from cathedrals into banks and coin purses, iconoclasm indirectly fueled the demise of traditional society and the rise of a new capitalist spirit.10

Against a forward-looking story that identifies gold as a modernizing motor, the nagging prevalence of decorative gold in Britain and its empire supports a contrary narrative that emphasizes continuity rather than a radical break. In this story, the rise of a modern credit economy shared space with a widespread “invention of tradition” that bolstered national identity with imagined relics from the past; an empire that depended as much on ornamental splendor as on economic and racial subordination; and an impulse to draw from the past in order to create a habitable present in the face of rising levels of population and class division. The point, in most such accounts, is less to wish away all modernizing tendencies than to present these as existing in an unstable equilibrium with conservativism.11 Gold played its part in all these backward glances, including the royal family’s gilded accessories, soldiers’ uniforms, and lord mayors’ coaches; efforts to out-glitter native princes whose territories fell under British subjugation; and ambivalence about the absence of adornment in British churches.

Besides offering new insight into the rise of the British nation, a reassessment of gold during the decades before 1850 complicates existing scholarship on the metal’s changing global role. This has almost exclusively focused on its monetary function; and even in that domain most of the attention has focused on the century after 1850, when other nations followed Britain’s lead in joining an international gold standard. In this domain, scholars who present the rise of the international system as the natural and beneficial consequence of new gold discoveries have contended with those who argue that it was both highly artificial and dangerously destabilizing.12 Recent scholarship has added a great deal to what we know about the cultural and institutional processes before 1850 that conferred legitimacy on money, credit, and the gold standard within Britain.13 Even so, little attention has yet been paid to the enormous amount of cultural work—only partially successful—that redirected attitudes away from the many other values gold possessed as a commodity. Much also remains to be learned about the material story of gold’s multiple roles as bullion, coin, and ornament during this time, both in Britain and the wider world.

The scope of this task is illuminated by the fact that only around half of all gold in Britain before 1850, and a much smaller share on foreign shores, circulated as coin or sat in bank vaults; the rest adorned churches, watches, plate, medals, canes, jewelry, and clothing.14 By emphasizing these other roles of gold, this book tells the commodity side of the story that lay behind the rise of the gold standard and enables a fresh perspective on its monetary side as well.15 In the process, it also counters a myth, dating back to Adam Smith, that capitalism works most efficiently when it transcends national boundaries—a myth that obscures the fact that nation-states have always acted as “an indispensable instrument . . . of global capital” and have also left distinctive and indelible cultural imprints on economic development within their borders.16 Historians who focus on the gold standard as a transnational, and mainly stabilizing, mechanism tend to downplay the tumultuous politics it often engendered in its member states.17 In Britain as well, during the decades when it was building a foundation for that mechanism, gold in both its monetary and ornamental forms was as likely to be destabilizing as disciplinary. Above all, attitudes about gold always drew from an emerging and self-consciously British national culture, which attached to gold its substantial ambiguities and internal contradictions.

One of the most important of these internal contradictions concerned the meanings that Scottish, Irish, and English people within the British Isles ascribed to gold.18 These were the most pronounced in the case of money: most people in Scotland and Ireland embraced Smith’s maxim that a well-developed credit system rendered gold needful but rarely relevant, while many in England insisted on a substantial stock of circulating gold coin as well as bank notes.19 Scots also harbored a contrary sense of the influence of gold in foreign relations, owing to a history of England’s use of that metal to influence Scottish affairs; while Irish Catholics loudly countered the standard British Protestant line on gold’s proper place in religious worship. In general, though, these were exceptions to a rule that gold united more often than it divided, especially within the same social class and whenever Britons of all stripes contrasted their use of the metal with those practiced elsewhere in the world.

The first two chapters of All That Glittered describe British attempts to contrast their own acquisition and use of gold with those pursued abroad. The first chapter, “Domestication,” recounts the eighteenth-century production and transit of gold from the Americas to Britain and traces efforts to contrast British industry and humanity with Iberian sloth, cruelty, and impolicy as a boastful justification for why so much Latin American gold ended up in the Bank of England. Chapter 2, “Value,” explores the ambivalence that ensued when Britons puzzled over what made gold valuable once it had appeared on their shores. It considers the political debate over Britain’s legal currency standard in the 1810s,

when it was still an open question whether gold, silver, or state-backed paper money would serve this purpose. It then turns to figurative references to gold, which alternated between godliness, genius, and purity and condemnations of adornment and avarice.

Chapters 3 through 5 focus on gold’s shifting function as a foundation of Britain’s political economy, relating to war expenditure, foreign trade, and coinage. “War” explores the political debates and paranoid imaginings that surrounded Britain’s bullion transfers to its allies and troops between 1756 and 1815. “Trade” describes gold’s important role in Britain's balance of payments between 1815 and 1850 and in accompanying debates over the merits or otherwise of free trade. “Coinages” covers the respective circulation of guineas and sovereigns before and after 1820, emphasizing the irony that these gold coins recurrently needed to be weighed by their users despite bearing stamps that attested to their legal weight and fineness. An important supporting actor in the first two of these chapters is credit, which extended the reach of bullion and coin but also tended to exacerbate conflicts among landlords, financiers, manufacturers, and laborers.

Chapters 6 through 9 interrogate British claims that they uniquely subordinated gold’s nonmonetary uses to its more “civilized” use as a basis of credit and commerce. “Distinction” describes efforts by upper-crust Britons to insist that gold should mainly be used as money, while they simultaneously carved out numerous exceptions that threatened to overwhelm this rule. “Display” discusses gold’s appearance in British ethnographies of people who broadcast their foreignness with ornamental gold, while “Devotion” examines British critiques of excessive adornment in non-Protestant churches and temples. These chapters all emphasize the large patches of ambivalence that blurred the alleged binary between British and non-British uses of gold. Chapter 9, “Graven Images,” discerns a parallel ambivalence about ancient gold coins and modern gold medals, which conjured nonmonetary (and, consequently, controversial) value by enabling Britons to discover their forebears, broadcast their erudition, or locate themselves in posterity.

All That Glittered concludes by returning to the theme of gold production, first in chapter 10, on British interests in gold mining between 1820 and 1848, and then in the conclusion, on the California and Australia gold rushes between 1848 and the mid-1850s. “Before the Gold Rush” recounts British efforts to find new sources of gold in Brazil, Russia, Africa, and Asia in order to enable the smooth functioning of their restored gold standard after 1820. In all these cases, their growing dependence on gold to maintain economic and political stability led them to blur previously bright lines between the sordid production of foreign gold and its beneficial use in Britain. These lines further faded with the gold rushes, which transformed the global money market and newly identified the

extraction of gold with the British Empire. They also restored British economic thought back to Adam Smith’s original lack of concern about ornamental gold, which emerged after 1850 as a safety valve against inflation.

Although these chapters are thematic, they all adhere to a chronology that can be roughly divided into three periods—the decades before, during, and after the Napoleonic Wars—that each betrayed distinctive monetary, ornamental, and political tendencies. The 1750s through the 1790s marked the swan song of the guinea, a coin that conjured aristocratic excess (“gold tables” where dandies dwindled their fortunes) and income inequality (the average laborer needed to work two weeks to earn a guinea in 1774).20 As ornament, gold during these decades signaled the end of an era, when doctors began to trade in their goldheaded canes for stethoscopes and country gentlemen started to shed the gold lace from their waistcoats and hats. Politically, Britain began to make military use of the gold it received from Brazil, first in support of its allies during the Seven Years’ War and then by paying mercenaries in an effort to quell the American Revolution.

It was this latter function of gold that precipitated the death of the guinea, the onset of which occurred with the suspension of cash payments by the Bank of England in 1797. This policy, which the British government deemed necessary to enable it to wage war against Napoleon, accompanied a substantial increase in prices by the war’s end in 1815. Inflation helped landlords (especially the substantial proportion of debt-ridden ones), who passed a corn law in 1815 to retain the high food prices and accompanying high rents they had enjoyed during the war; and gave them ample capacity to spend their bank notes on ornamental gold, which enjoyed a surge in popularity even while military demands drained the country of its guineas. It ceaselessly bothered creditors, who feared the resultant diminishing returns on their loans. The French, for their part, diverted much gold from church treasuries into their war chest, which effected an ironic culmination of many Britons’ anti-Catholic fantasies.

Soon after 1815 Britain returned to the gold standard and marked the occasion with a new coin, the sovereign, worth a shilling less than the guinea. The return to gold drove down prices for everyone except grain producers, ensnaring gold in a heated debate over the relative merits of self-sufficiency versus global interdependence. It also prompted prosperity, although this was uneven and volatile, and accompanied an unprecedented diffusion of sovereigns as well as ornamental gold. Aristocrats, meanwhile, found new corners where they could display gold in ways that reinforced social hierarchy, while newly influential aesthetes started to erode a centuries-old resistance to devotional gold in British churches. Most of these changes reflected a political structure that included more middle-class and Catholic voices. A revived British Empire, finally, afforded new opportunities to identify gold with cultural difference, which informed

free-trade debates along with commentary on Asian and African adornment— as well as prompting wishful thinking about new gold mines.

Throughout the centuries after 1492, whether gold was used as ornament or as money, it inspired envy and greed—and the fact that gold ornaments could be converted so easily into money rendered them especially prone to pillage. Britons often claimed that they peacefully acquired gold through commerce instead of violently plundering it, in contrast to Spain during the Conquest and France during the decades after 1789. Yet try as they might to insist on this, violence was seldom far from the surface in British encounters with the metal. Elizabethan privateers gave Spaniards a run for their money in the business of plunder, while colonial conquests in South Asia appropriated much gold as well as land. The simplicity that British Protestants celebrated in their cathedrals rested on the awkward foundation of Tudor looting. Britain’s efforts to find new sources of gold after 1820 brought them into direct contact with serfdom in Russia, slavery in Brazil, and social chaos in California and Australia. Finally, a corollary of gold’s ascendance in Britain after 1750 was the mounting frequency of its appearance in criminal courts. Although the particulars changed over time, one constant theme throughout this period was a rearguard effort to contain such violence by diverting attention to financial institutions such as the Bank of England, which strove to solidify gold’s disciplinary potential in the face of exceptionally bad behavior.

As nineteenth-century geologists often observed, gold was both well concealed and “widely scattered throughout the mineral kingdom.” Gold was literally everywhere, although not always in amounts that made prospecting for it worthwhile. Indeed, for the entire period covered in this book, gold miners settled for panning streams, using steam technology for crushing rocks, and applying mercury to separate gold from its ore; it was not until the late-nineteenth century that new chemical processes enabled an explosion in world gold production.21 These features all apply to the challenge of researching a comprehensive cultural and monetary history of gold. References to its manifold forms are everywhere, from gothic romances to currency pamphlets—as well as sermons, hymnals, travelogues, histories, conduct manuals, encyclopedias, poems, plays, newspapers and periodicals of all varieties, Parliamentary speeches and committee reports, and criminal trials.22

Until the recent past, finding such references—except in the minority of cases where gold appears in the title or subject heading—would rarely have repaid the time and effort it took to call up volume after volume and sift through each for the pages where gold makes its brief appearance. The arrival of searchable electronic databases has transformed access to these dusty corners—although not without introducing a danger of losing track of the wider context or neglecting

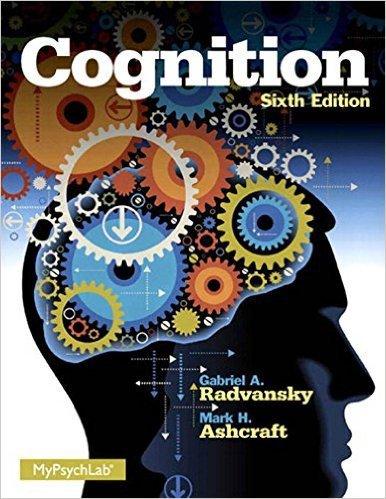

the databases’ built-in limitations.23 This book uses these resources extensively in order to expand its range of available primary sources. Even in instances of quantitative analysis, the findings are suggestive (appealing to proportions, not absolute numbers) rather than definitive; hence a common criticism of these databases, which concerns their sins of omission, applies with less force.24 Regarding the extent and composition of these primary sources, this table indicates the electronic resources used:

Google Books 8764

Making of the Modern World (Gale) 5790

British Periodicals (ProQuest) 4229

Eighteenth Century Collections Online (Gale) 4225

Gale News Vault and 19th Century Periodicals 3161

Other 1674

Other: Hansard 1803–2005 (Millbank Systems), House of Commons Parliamentary Papers (ProQuest), Old Bailey Online, and English Verse Drama (Chadwick Healey). Number of discrete sources = 27,843. By discrete sources I include multiple references to different themes from the same publication; the total number of books and articles consulted was roughly half this number.

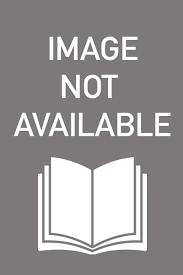

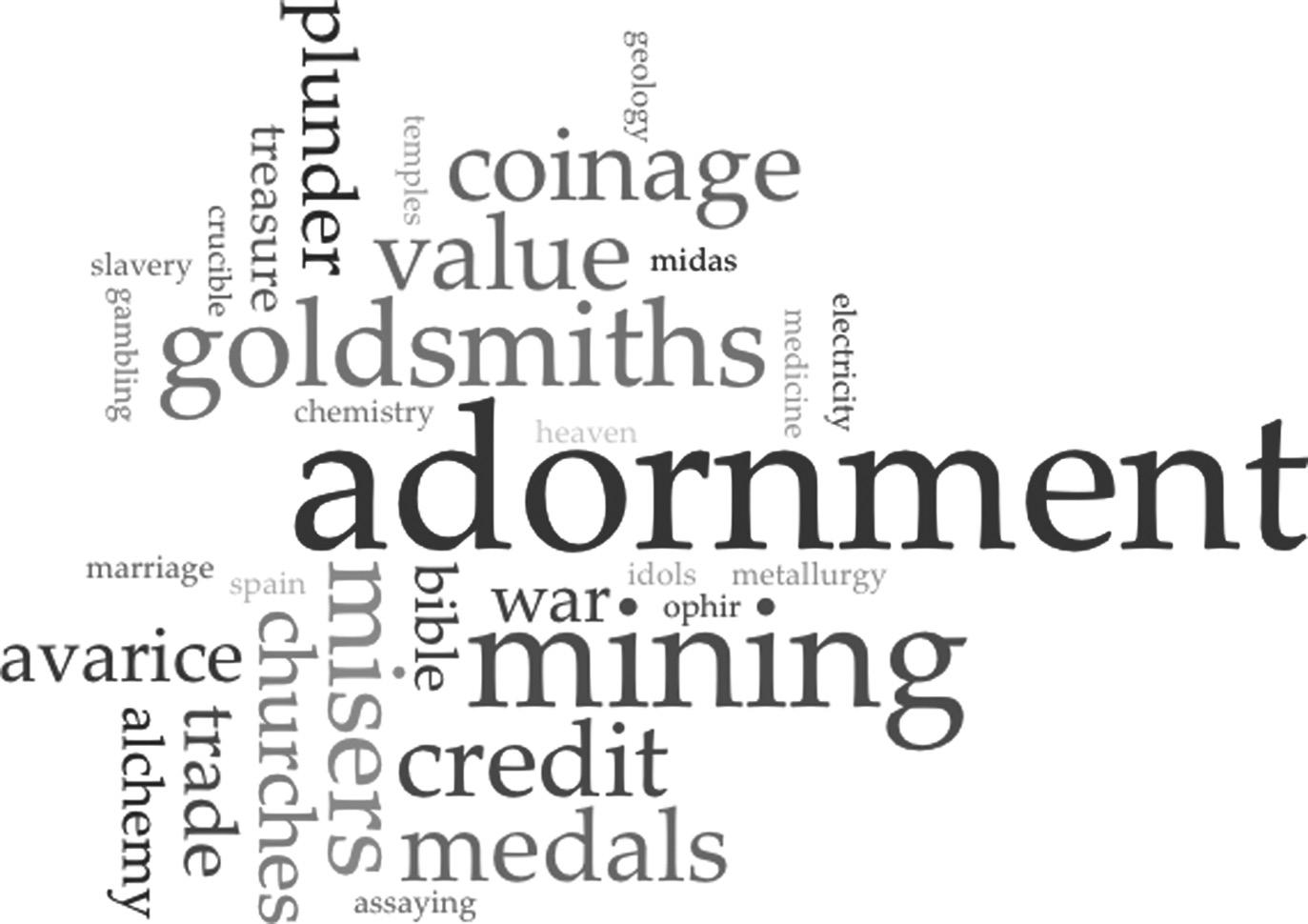

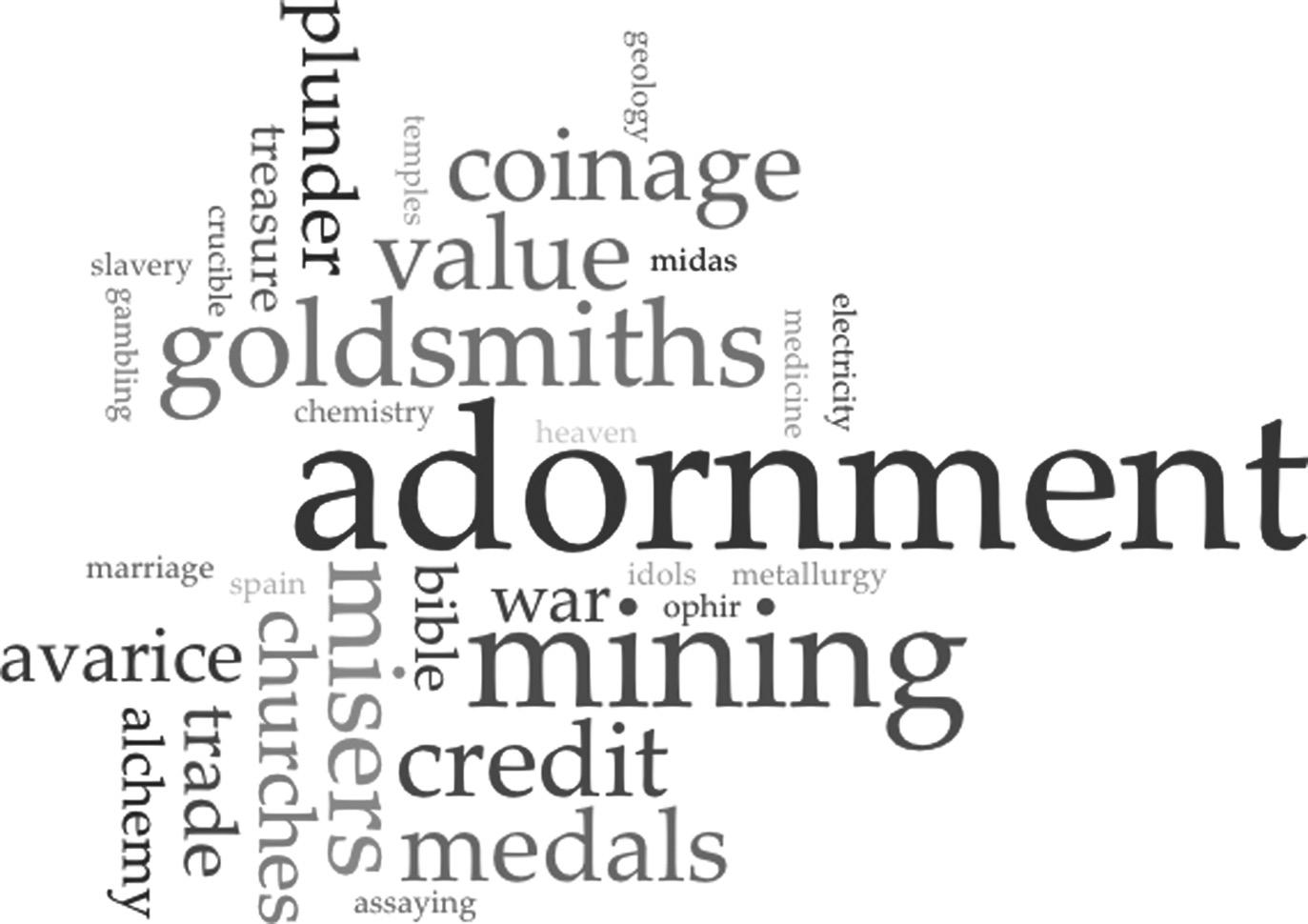

A word cloud provides a glimpse into the number of hits, organized thematically. Most of these fit snugly in one or two chapters, while plunder appears in all but two.

A few clues regarding the genesis and evolution of All That Glittered can be gleaned from this word cloud. First, the prominence of personal adornment: goldsmiths and gilding (more hits than any other category by 4000) led to the allotment of equal time to this use of gold, a hunch that Smith’s evocative and influential story about value reinforced. Second, the hundreds of references to gold as an instrument of war justified a stand-alone chapter on that topic; the same reasoning applied to coinage, buried treasure, and gold medals. Third, although references to gold as a basis of credit were rife, less time was devoted to this topic, since other scholars have ably discussed much of this material already. Finally, as with any project, many references either did not conveniently fit this story, would have led the book to balloon in size, or both, including alchemy, medicine, misers, and gold’s many appearances in the Bible.25

A final word about the search process used in researching this book is in order: namely, regarding the presence or absence of gold’s leading supporting actor, silver. With a few exceptions, silver was not one of the search terms used in finding the sources that went into All That Glittered—despite that fact that,

Figure I.1 Word cloud representing the frequency of references to gold found in the primary-source electronic databases consulted, organized by theme (total number, excluding “miscellaneous,” = 27,214): personal adornment (4893), mining (3094), goldsmiths and gilding (2092), credit (1909), coinage (1599), medals (1458), trade (1119), churches (1086), avarice (1075), plunder (953), war (928), treasure (713), alchemy (710), Bible (708), misers (654), crucible (550), Spain (302), idols (297), chemistry (285), temples (253), medicine (178), Ophir (171), Midas (168), metallurgy (159), assaying (128), electricity (78), slavery (74), marriage (69), gambling (52). By discrete sources I include multiple references to different themes from the same publication; the total number of books and articles consulted was roughly half this number.

as Shakespeare immortally implied, silver is one among many substances that glitters along with gold. The challenge of referring to silver in what is tantamount to a biography of gold parallels that of determining how much time to spend on a spouse or sibling in a biography of a human being. This was different, depending on the uses of gold discussed in the pages that follow. As money, Britain’s preference for gold over silver is central to the story, with the result that the relationship between the two metals frequently appeared in contemporary debates. As adornment, and as money in regions that were not on the gold standard, the difference between the two metals was more often a matter of degree and relative scarcity than of economic policy. In these cases, gold and silver often featured together in descriptions of display, devotion, and plunder. A more general book about ornamental British metals and gems would have been more inclusive but

less capable of making the connections among money, ornament, and national identity that are the primary focus here.26

The wide variety of contexts in which Britons remarked on gold testifies to that metal’s protean qualities: it was, and remains today, subject to an enormous range of meanings, depending both on the form into which people molded it and the sort of people who possessed it. The same quarter-ounce of gold that originally bore the stamp of a Roman emperor might be retrieved from a ditch and turned into a guinea, a medal, an earring, an epaulette, or a communion plate; and the earring might signify very different things if worn by an English belle, an Italian peasant girl, a statue of the Virgin Mary, a Spanish pirate, or a Brahmin merchant. Even in its more contained role as money, gold was always both a commodity, subject to export as a means of balancing trade, and a precise signifier of value, as indicated by whichever national symbol it temporarily bore. It is the object of this book to follow gold’s lurching, wide ambit of meanings around Britain and the world, which tended to cluster around an evolving national identity that took pride in being simultaneously traditional and modern.