ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Just like the work of public health, editing a book is a “team sport.” We would like to thank our team, all of whom had instrumental roles in moving this idea across the finish line as the complete volume you are reading. First, we acknowledge all of the authors who were core members of the team. Our authors and contributors willingly shared their expertise with us and graciously accepted edits and additions to their chapters. Philicia Tucker provided excellent administrative oversight of the development of this book and admirably served as our Chief Author Wrangler and liaison with our colleagues at Oxford University Press. The Oxford University Press team was instrumental, vital, and ever encouraging: Thanks to Chad Zimmerman, Chloe Layman, and Niveda. The staff at the Association of County and City Health Officials (ASTHO), including Christi Mackie and Andy Baker-White, were important to supporting several pieces in this book and provided expert advice and feedback. Finally, we thank our “home team”—those who supported and sustained us during long hours and late nights of editing and organizing this book’s content despite amazingly busy “real jobs.”

For everyone’s efforts, we are truly grateful.

Jay C. Butler

Michael R. Fraser Editors

FOREWORD: A RECOVERY JOURNEY

GReG WilliaMs

My name is Greg Williams and I am a person in long-term recovery from addiction. There are many deeply important layers to those 15 short words. My journey through addiction culminated in heavy use of opioids as an adolescent. It was not a journey I sought out; in many ways it “just happened.” For reasons I could not explain then, but have more clarity around now, in three short years my seemingly innocent use of marijuana and alcohol as I was just becoming a teenager manifested into an opioid dependency beyond my control.

It was 1999, I was 15 years old, and the early signs of the opioid crisis were just beginning in Appalachia—but I was in Stamford, Connecticut, just 40 minutes from the other “ground zero.” Doctors were being shamed for not treating pain patients appropriately and pain pills had begun to show up en masse in medicine cabinets across the country. Peers introduced me to diverted opioids and benzodiazepines. We would promptly look up the imprint codes on the pills using the internet to ensure they had “good” side effects. It started innocently enough, but what transpired next—addiction—was not something I signed up for or chose.

In The Anonymous People, a feature-length documentary film I produced on this topic (Figures I.1 and I.2), I chose to visualize the lack of choice I felt by slowly zooming in tight on an image of my high school yearbook photo while narrating: “Public perception of addiction to alcohol and other drugs continues to be something very different than the science. What that perception does is look at this 15-year-old kid, with a genetic predisposition and still-developing brain, and suggest I made an independent, rational choice to become addicted.”1

What is important now is that we use a science-based understanding of addiction to end the crisis. Addiction is not a choice. Addiction is a chronic disease of the brain and, as with any chronic disease, it requires quality, evidence-based treatment and active public health education and health promotion campaigns to prevent it.

My recovery was established in 2001, after a near-fatal car accident at age 17 landed me in the hospital, and then an adolescent psychiatric unit, then a quality adolescent addiction treatment program, then a recovery house for 90 days. Recovery was not my idea. I was a reluctant participant and thought of myself as “too young to be an addict.” Today, I realize my belief that I was too young to struggle with addiction came from the media messages surrounding the topic. I was born in 1983, and my childhood included the fear-driven era

Figure i.1. The Anonymous People movie poster.

where people who used drugs were viewed as “public enemy number one.” The images and messages transmitted to me were not of young high school kids smoking marijuana, drinking alcohol, or taking pills. They were of older people most often using crack cocaine or injecting heroin. I could not relate to those images at the time and therefore thought, “I must not be an addict.”

It took a lot of time, a lot of education, a lot of therapy, and a lot of selfacceptance to overcome those deeply entrenched beliefs about what addiction is and that it actually impacts young people. Today, I am grateful to be alive and not incarcerated, given the volume of substances ingested and the risky and illegal behavior I engaged in as an adolescent suffering from a substance use disorder. As a result of my personal freedom from active addiction, not only have I survived one of the deadliest health problems facing young people in America today, but I have thrived. I have been blessed with incredible opportunities to learn, chase dreams, and live a life full of purpose. I am not alone: There are 23 million other Americans living in recovery. That is more than those who are currently struggling with all substance use disorders combined, including opioids.2 But historically we have been a silent and marginalized group of people. I was actually taught in recovery to stay anonymous out of the fear of future discrimination I might face if I told my story.

Individuals in recovery and their families are a heterogeneous group and have never collectively mobilized and organized to affect policy, change our culture, and attract others to life in recovery. There are deep parallels to what

Figure i.2. Greg Williams at the UNITE to Face Addiction Rally, Washington, DC, October 4, 2015. (Photo credit: National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and Kate Meyer.)

we face and what is possible to overcome when looking at the HIV/AIDS movement in the late 1980s and early 1990s, led in large part by the LGBT community. However, a revolution in cultural perception requires a united message of the reality of recovery to shift public discourse, change stigma, and ultimately improve policy responses. Desperately needed are robust local, state, and national advocacy efforts aimed at informing the transition from a criminal justice–centered approach toward a health-centered approach that will improve prevention, treatment, and recovery policies across all systems.

In his book Let’s Go Make Some History: Chronicles of the New Addiction Recovery Advocacy Movement, William White argues that existing “underground” recovery communities hold the answers for the future grounded in a new public recovery movement.3 Understandably, some people in recovery are reluctant to go public with their addiction status. But when someone does tell his or her story and put a face and a voice on recovery, the public can finally access the powerful message of hope that has resonated for years in these underground recovery communities. At the end of each interview of the nearly 100 recovery community leaders for my The Anonymous People documentary, I would ask interviewees about their vision for the future. Almost all of them said they wanted to “one day see thousands of people like me, our families, and those who have lost loved ones gather on the National Mall to create a moment just like other civil rights movements in our country’s history have done” (Figure I.3).

In 2015, as the death toll from opioids was rising to unfathomable levels, it became apparent that this was our moment. And in the face of incredible odds, we did it: we gathered on the National Mall in Washington, DC, and marked a turning point in American history. The start of the chapter “Recovery” in the first-ever Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health: Facing Addiction in America begins with this passage:

On October 4, 2015, tens of thousands of people attended the UNITE to Face Addiction rally in Washington, D.C. The event was one of many signs that a new movement is emerging in America: People in recovery, their family members, and other supporters are banding together to decrease the discrimination associated with substance use disorders and spread the message that people do recover.4(p. 5)

On that dreary cold day on the National Mall we launched the “Facing Addiction” movement, which in just over two short years has merged with the oldest national advocacy organization battling alcohol and other drug problems, the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD). Our visionary founder, Marty Mann, understood that addiction was an illness that must be treated as a public health problem. Her vision, forged in 1944, is based on two significant focal points:

• People with the illness of addiction can be helped and are worth helping.

• Addiction is a public health problem and, therefore, a public responsibility to address.

Facing Addiction with NCADD, the merger of Facing Addiction and the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, now provides a national platform for a coalition with over 850 Action Network Partners, 80 affiliate organizations, and a national voice of grassroots advocacy for individuals and families impacted by addiction. People in recovery from addiction, our families, and our allies have a duty to respond to the ignorance, prejudice, and injustice that continue to pervade our culture. Lives depend on it. In spite of a broken system and failed community response, many of us have been given the gift of recovery, and that can have profound cultural, political, health care, criminal justice, and economic implications.

Few people are aware that through recovery, more than 25 million of us have gotten well, families have been reunited, and our communities have been the ultimate beneficiary. Congress does not believe we exist in such significant numbers (yet) and the media continue to ignore this major facet of the addiction story. It is our duty to share our stories with a unified message to a new audience so that future generations can live free from the greatest barriers to recovery: stigma, shame, and discrimination. Like many health professionals, public health practitioners are important allies in this work,

Figure i.3. Crowd at the UNITE to Face Addiction Rally, Washington, DC, October 4, 2015. (Photo credit: National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and Kate Meyer.)

including those who have the lived experience of recovery, know loved ones who are battling with addiction, know loved ones who have recovered, and see the ravages of addiction in communities nationwide and what is possible when we dedicate ourselves to and invest adequately in addiction prevention and treatment and recovery programs. No matter how addiction has touched your life or a loved one’s, I invite you to consider becoming one of the many emerging faces sharing the recovery stories in harmony with a growing chorus of revolutionaries.

References

1. The Anonymous People. [DVD] Directed by G. Williams. Van Nuys, CA: Dimension Productions; 2013.

2. Recovery Research Institute. 1 in 10 Americans report having resolved a significant substance use problem. https://www.recoveryanswers.org/research-post/1-in-10americans-report-having-resolved-a-significant-substance-use-problem/ [no date]. Accessed December 19, 2018.

3. White WL. Let’s Go Make Some History: Chronicles of the New Addiction Recovery Advocacy Movement. Washington, DC: Johnson Institute Foundation; 2006.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: HHS; 2016.

FOREWORD: COUNTERING THE OPIOID EPIDEMIC

Meena VythilinGaM, kuMiko liPPolD, anD BRett P. GiRoiR

The ongoing epidemic of opioid addiction and opioid-related deaths is devastating communities, families, and individuals across our nation. In 2017 alone, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 70,237 Americans died from drug overdoses1 and the majority (47,600) of these deaths involved opioids.2 More than 130 Americans die every day from an opioid-related overdose and an estimated 2.1 million Americans aged 12 and older meet the criteria for opioid use disorder (OUD).3 The economic cost of our nation’s opioid crisis in 2015 alone was a staggering $504 billion, equating to approximately 2.8% of the US gross domestic product (GDP).4 The opioid crisis is the most important public health crisis of our time and combating it remains a top priority across our agency, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and for the Trump administration as a whole.

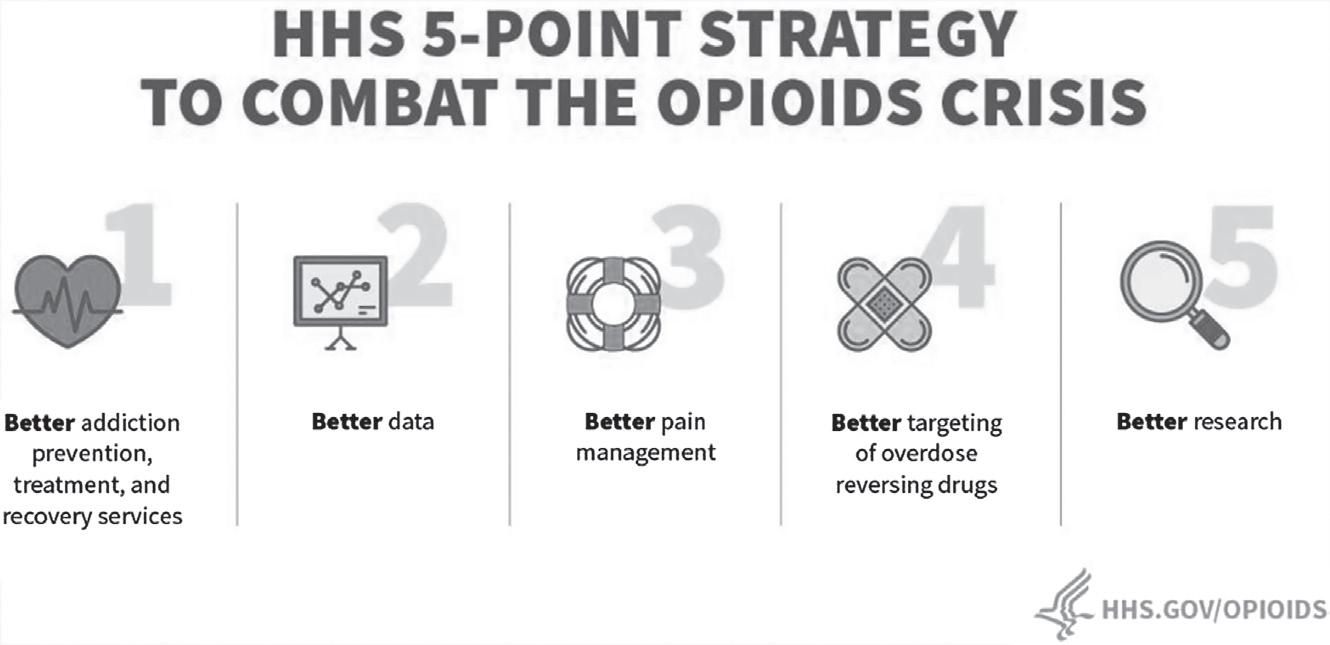

The far-reaching devastation caused by the opioid epidemic has necessitated the design and rapid implementation of a strategic plan that incorporates the latest research findings and evidence-based practices.5 Partnerships and collaborations across public, private, nonprofit, and academic health systems are critical in defeating the opioid scourge. The HHS Office of Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH) plays a key role in coordinating the numerous federal initiatives related to opioids and pain and has prioritized a five-pronged public health strategy to address this public health emergency (Figure II.1). The strategies are described below.

Figure ii.1. HHS 5-point strategy to combat the opioids crisis.

Source: HHS.GOV/Opioids.

Access: Better Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services

In 2018, HHS invested more than $4.4 billion to combat opioid abuse, misuse, and overdose deaths by funding treatment, prevention, and recovery efforts. States, tribes, and communities across America can apply for these newly appropriated funds to address the opioid crisis. In addition, the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) launched two innovative programs, the Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) model and the Integrated Care for Kids (InCK) initiative, to address gaps in coordinated care for pregnant and postpartum women with OUD and their children. Recent improvements in access to evidence-based treatments are supported by the fact that the number of unique patients with OUD receiving buprenorphine, a medication-assisted treatment (MAT) option, has increased by 31% per month between January 2017 and May 2019.6

Data: Better Data on the Epidemic

The ever-changing landscape of the opioid epidemic requires constant vigilance and situational awareness. The CDC leads a robust surveillance program to monitor the opioid crisis. CDC publishes monthly updates on drug and opioid mortality at the national and state levels, including longitudinal trends, and the reported and predicted number of overdose deaths. In addition to fatal overdose deaths, data on nonfatal overdoses and syndromic surveillance data from 32 states and the District of Columbia are analyzed by CDC’s Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance (ESOOS) program, which serves as an

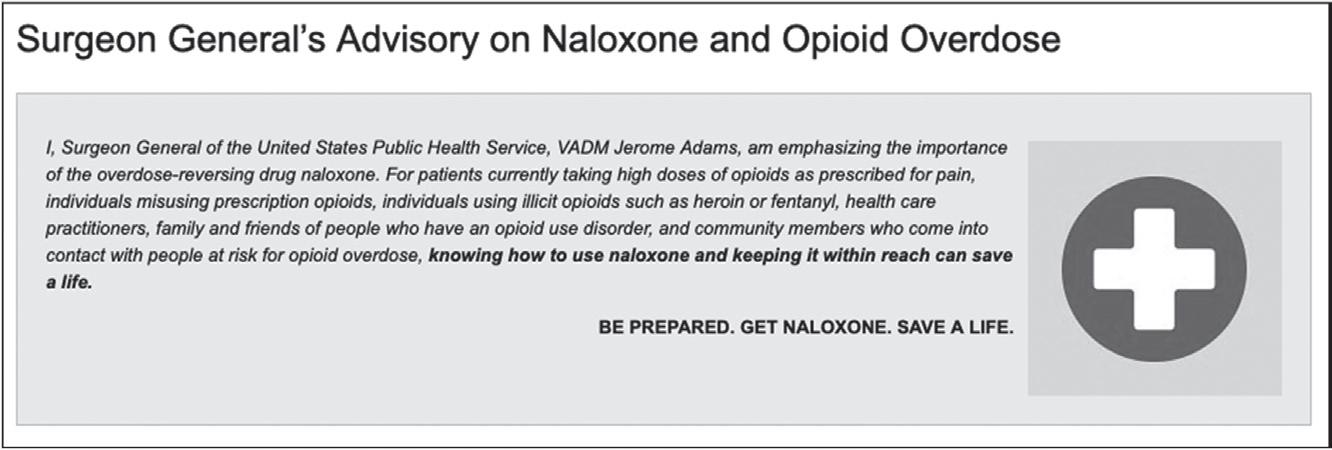

Figure ii.2. Surgeon General’s advisory on naloxone and opioid overdose.

Source: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/opioid-overdose-prevention/naloxone-advisory.html

early warning system to help identify opioid overdose outbreaks. Together, these CDC programs provide critical surveillance data that can inform national, state, and local opioid prevention efforts and assist with targeted resource allocation.

Pain: Better Pain Management

Since overprescription of opioids by clinicians initially contributed to this epidemic, undoing this crisis will involve educating clinicians about the risks of opioids and the importance of adhering to evidence-based prescribing guidelines. Providing evidence-based pain management is also a critical step in preventing inappropriate exposure to prescription opioids. The publication of the CDC’s Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain and the Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force recommendations represent two examples of collaborative efforts to translate the latest science into clinical practice.7,8 Federally funded prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) allow for state- and territorial-level interventions to monitor appropriate prescribing of opioids, influence clinical practice, and protect at-risk patients.

Overdoses: Better Targeting of Naloxone

Improving access to naloxone, the lifesaving opioid overdose-reversing medication, is an effective approach to prevent opioid related deaths. In April 2018, the Surgeon General’s Advisory on Naloxone and Opioid Overdose emphasized the importance of increasing naloxone access to at-risk patients, their friends, family, and the local community (Figure II.2).9,10 The number of monthly naloxone prescriptions has increased by more than 504% from

January 2017 to May 2019,6 in addition to millions of doses being distributed directly to states, municipalities, first responders, and nonprofit organizations. Clinicians are advised to co-prescribe naloxone for patients who are also receiving opioids at doses greater than 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) or other risk factors such as sleep apnea and OUD.

Research: Better Research on Pain and Addiction

HHS, through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), supports cutting-edge research to elucidate the neurobiology of pain and addiction in order to develop novel treatments. This is exemplified through Helping to End Addiction Long Term (HEAL), an NIH-led, multi-agency effort to advance recent research and translation of scientific solutions into clinical practice by facilitating public–private partnerships.

Preliminary data suggest that these upstream and downstream efforts across the continuum of care are beginning to make inroads into the opioid crisis. The total number of opioid prescriptions dispensed monthly by pharmacies has declined by approximately 21% from January 2017 to May 2019,6 the number of patients receiving medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has increased, and the extent of opioid pain reliever misuse and first-time heroin use has also decreased substantially according to the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.3 According to provisional data from the CDC, the seemingly relentless trend of rising overdose deaths seems to be slowing and the curve is finally bending in the right direction. However, plateauing at a still high opioid-related mortality rate is hardly an opportunity to declare victory. It is critical to maintain a sense of urgency and continue an “all hands on deck” approach in order to win this war against opioids.

To reiterate, the opioid epidemic will only be curbed by a “whole society” approach, for which the role of state and territorial health officials and other public health practitioners is both central and essential. As key leaders of the public health response in their respective jurisdictions, public health officials can provide strategic direction and technical guidance to stakeholders at all levels of the government, including city, county, and tribal agencies, to ensure that we win the opioid war. Public health practitioners are critical to implementing evidence-based treatment, recovery, and prevention programs. There are multiple opportunities for all health care professionals, legislators, law enforcement officials, and the general public to help curb the tide of opioid overdose.

Communities can implement CDC’s 10 evidence-based strategies for preventing opioid overdose (Text Box II.1), including establishing syringe services programs, and the public should provide input into the activities of HHS through advocacy and submitting public comments on opioid policies and

TEXT BOX II.1 TEN EVIDENCE- BASED STRATEGIES FOR PREVENTING OPIOID OVERDOSE

1. Targeted naloxone distribution

2. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT)

3. Academic detailing

4. Eliminating prior-authorization requirements for medications for opioid use disorder

5. Screening for fentanyl in routine clinical toxicology testing

6. 911 Good Samaritan laws

7. Naloxone distribution in treatment centers and criminal justice settings

8. MAT in criminal justice settings and on release

9. Initiating buprenorphine-based MAT in emergency departments

10. Syringe services programs

For more information on these strategies, visit: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018-evidence-based-strategies.pdf

programs.11 Finally, health professionals, friends, families, and the judicial and law enforcement communities can help reduce stigma by recognizing OUD as a brain illness and encouraging individuals to seek treatment. Only then can we bring our brothers, mothers, daughters, and friends back to their loved ones.

References

1. Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Spencer MR, et al. Provisional drug overdose death counts. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm. Accessed February 5, 2019.

2. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no. 329. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329-h.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2019.

3. US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 national survey on drug use and health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/ cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2019.

4. Council of Economic Advisers. The underestimated cost of the opioid crisis. https:// www.whitehouse.gov/ briefings- statements/ cea- report- underestimated- cost- opioidcrisis. 2017. Accessed February 5, 2019.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Strategy to combat opioid abuse, misuse, and overdose: A framework based on the five-point strategy. 2019. https:// www.hhs.gov/ opioids/ sites/ default/ files/ 2018- 09/ opioid- fivepoint- strategy20180917-508compliant.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2019.

6. IQVIA National Prescription Audit. Data retrieved on November 9, 2018. Note: Data presented for the retail and mail channels only

7. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wklyl Rep. 2016; 65(No. RR-1):1–49.

8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2019, May). Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. Retrieved from U. S. Department of Health and Human Services website: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/index.html

9. Adams JM. Surgeon General’s advisory on naloxone and opioid overdose. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/ priorities/opioid-overdose-prevention/naloxone-advisory.html. Accessed February 5, 2019.

10. Adams JM. Increasing naloxone awareness and use: The role of health care practitioners. JAMA. 2018; 319(20):2073–2074.

11. Caroll JJ, Green TC, Noonan RK. Evidence-based strategies for preventing opioid overdose: What’s working in the United States. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2018. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018evidence-based-strategies.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2019.

1 Introduction

Why a Public h ealth g uide to e nding the oP ioid c risis?

Michael R. FRaseR anD Jay c. ButleR

Few contributions to the field concerning the current opioid crisis in the United States focus sufficient attention on the public health aspects of the epidemic and share actual examples that practitioners can use to learn how to successfully integrate primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies across multiple sectors to prevent opioid use disorder and the broader issues of substance misuse and addiction. Justifiably, a great deal of prior work has concentrated on health care and clinical perspectives related to the crisis due to the exponential rise in opioid-related overdose deaths and the urgent demand for access to evidence-based treatment and recovery programs. This work includes developing prescribing guidelines, enhancing prescription drug monitoring programs, scaling up access to overdose reversal medication, and making medication-assisted treatment (MAT) more widely available nationwide. However, in our review of many of the efforts to end the epidemic, comparable attention has not been paid to the central tenets of the public health approach. These tenets include (1) how to best support community-based, primary prevention of substance misuse and addiction in various settings with diverse populations, (2) how to prevent addiction across the life course using a public health approach, and (3) how to effectively address the cultural, social, and environmental aspects of health that are driving the current epidemic.

The paucity of research on and practical guidance for how local, state, and federal governmental public health agencies and their partners can move “upstream” to respond to the crisis, and lead community partnerships to end it, drove us to propose this Guide and engage so many talented colleagues to produce it. All of the authors who contributed to this work are personally and/ or professionally engaged in responding to the crisis from different vantage points inside and outside of government, from the center and periphery of

Michael R. Fraser and Jay C. Butler, Introduction:WhyaPublicHealthGuidetoEndingtheOpioid Crisis?. In: APublicHealthGuidetoEndingtheOpioidEpidemic. Edited by Michael R. Fraser PhD MS, Jay C. Butler MD and Philicia Tucker MPH, Oxford University Press (2019). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190056810.003.0001

public health practice, and from their lived experience of recovering from substance use disorder and addiction or supporting individual recovery journeys as family members and friends, and as practitioners working with and managing individual patients and entire communities facing addiction.

The contributions in this volume describe how public health has played a significant role in responding to the epidemic, in public health’s traditional approach to disease surveillance and control but also in contemporary approaches to health promotion that include building community resilience, addressing the impact of adverse childhood events (ACEs), and mitigating the root causes of addiction community-wide. This Guide also describes the multiple partnerships public health agencies need to develop with many different stakeholders, including substance abuse and drug and alcohol program directors, primary and specialty health care providers, law enforcement and corrections officials, health care insurers and payers, medical societies, community development organizations, and myriad others.

While we intended the Guide to be comprehensive, there are many facets of the crisis that are not included in this volume due to the sheer number and variety of ways public health is responding to the crisis and the many different approaches being taken to end it. The contributions herein emphasize the role of public health practice in the prevention of substance misuse and addiction or represent the work of a sector with which public health needs to become much more closely engaged. The chapters in Part I highlight fundamental frameworks and approaches to understanding the crisis from the vantage point of public health and share information that public health practitioners should consider as they develop contemporary opioid response programs and policies. Part II examines the ways that public health and health care partners, including providers and payers, have worked together to address the epidemic from the nexus of clinical medicine and community health practice. This focus on clinical practice is important given the existing focus on secondary and tertiary prevention, the urgent need to expand screening and treatment for substance misuse and addiction, and the tremendous opportunities for improving health that come from integrated public health and health care partnerships. In Part III, contributions illustrate the need for comprehensive, systems-level approaches that address the drivers of the crisis and the multiple leverage points at which public health can intervene to end it. Part III also includes an exploration of what it really means to address primary prevention of addiction, ways that public health agencies have used their traditional surveillance and epidemiology roles to better understand the epidemic, and how public health practitioners can develop new models to support “opioid stewardship” at the local, state, and federal levels.

As the Assistant Secretary of Health Dr. Brett Giroir and his team at the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) describe in the foreword to

this volume, federal health officials have laid out five key strategies to address the opioid crisis. National leadership to end the crisis has been galvanized through state and federal emergency declarations and by high-level strategy development meetings between cities, states, and federal officials at the White House and HHS. Congress has prioritized treatment, recovery, and prevention and appropriated billions of new dollars to develop new and expand current programs.

The new political will and increase in fiscal resources are vital to reaching a goal we all share: ending the current epidemic of overdose deaths, as we also address the broader and longstanding problems of substance misuse and addiction of which opioid misuse is but one part. But these new resources did not come with a step-by-step protocol or instruction manual that could be applied to all communities in the same way. For example, expanding access to MAT will look different in a rural or frontier state, or a state that has expanded Medicaid versus a state that has not. Another reason is that sharing what is working and describing the public health role takes time that most public health practitioners do not have: They are busy responding to the crisis and doing the work urgently needed to address overdose deaths in their jurisdictions. Many of the contributors to this volume agreed to write their chapters knowing that it would be done on nights and weekends, or another “duty as assigned,” but also knowing that sharing their contribution could have significant impact on the lives of others through describing their experience or sharing their knowledge. As Greg Williams aptly reminds us in his foreword to the Guide, recovery is possible and sustainable, and success is achievable, but more needs to be done to support the community of those in recovery and to prevent substance misuse and addiction in the first place.

While titled a “guide,” this volume may more aptly be described as a collection of stories about how talented, dedicated, and inspiring leaders have taken a variety of efforts to prevent opioid misuse and addiction. It is not a cookbook with a list of ingredients to be assembled and prepared or a Google map with all the steps clearly laid for the journey. Instead, this Guide shares the diverse experience and insight of seasoned researchers and practitioners about the current crisis and efforts to end it. The application and implementation of the lessons and insights they share in each chapter then become the purview of readers, who, we hope, will be inspired and informed by its contents. If our readers feel a little overwhelmed by all that needs to be done to achieve a lasting and sustainable impact, our goal of painting an accurate picture of the situation will be met. But working together across sectors, we are confident that a lasting and sustainable impact can be achieved.

Public health practitioners know that there is no way to end the current crisis without addressing the broad social, economic, and environmental factors that have created and sustained its growth, factors that go well beyond

changing the prescribing behavior of health care providers and interrupting the supply of illicit opioids. Naloxone dispensing, monitoring prescribing behavior, expanding access to MAT, increasing the use of alternative treatments for pain, and researching new cures for addiction all need to be complemented by approaches that address the demand for opioids in the first place. This involves working in what Fraser and Plescia refer to as the public health “sweet spot”:1 the primary prevention of substance misuse and addiction and working to expand evidence-based programs and policies that promote healthy communities and build individual, family, and community resilience. We understand that until we truly address the root causes of addiction, it will be difficult to end the crisis once and for all. To put it another way, we are not going to arrest or treat our way out of the opioid crisis; instead, we have to focus on preventing it. This Guide is intended to help show where we have been in these prevention efforts, where we are today, and where we are headed in the future.

Reference

1. Fraser M, Plescia M. The opioid epidemic’s prevention problem. Am J Public Health. 2019; 109(2):215–217.

The Emergence of an Epidemic

elizaBeth M. FinkelMan anD J. Michael McGinnis

The opioid epidemic stems from roots that course deeply throughout human history but whose alarming recent spread has positioned it as the most rapidly increasing killer of Americans. Derived from the extract of seeds of a poppy plant that has been growing on the planet for thousands of years, the use of opium poppy by humans may reach back more than 5,000 years to Mesopotamia, when the Sumerians began systematically using it for both medicinal and recreational purposes. With the advent of broad ocean travel and trade, opium became a focus of commerce, and, as often occurs in matters of trade, a prominent object of competition and conflict.

Today, the United States finds itself in the throes of a devastating opioid use epidemic, the deadliest addiction crisis of our time. Between 1999 and 2016, the US opioid epidemic claimed the lives of over 350,000 Americans.1 Driven by the epidemic, drug overdose is now the leading cause of unintentional death in the United States, taking the lives of over 170 Americans every day. Overdose has become the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of 50, and its toll continues to worsen. In 2016, over 64,000 Americans died from drug overdose, a 21% increase from 2015, and of those deaths approximately 42,000 were linked to opioids. While the crisis does not discriminate in terms of who or where it touches, opioid overdose deaths are most common among non-Hispanic whites, among individuals aged 25 to 54 years old, and in the Northeast, Midwest, and Southern US Census Bureau regions. Beyond the devastating human toll, the epidemic has inflicted a tremendous economic burden. A 2018 report estimated that the epidemic cost the nation about $1 trillion between 2001 and 2017, and it is projected that it will cost the economy an additional $500 billion between now and 2020.2

With consequences that are tragic and unprecedented, the opioid epidemic will leave an impact that spans generations of Americans. As various sectors seek to mobilize cooperatively to identify solutions, this chapter explores the origins of the epidemic. With root causes that are multiple and complex, a

Elizabeth

M.

Finkelman

and

J. Michael McGinnis,

TheEmergenceofanEpidemic. In: APublic HealthGuidetoEndingtheOpioidEpidemic. Edited by Michael R. Fraser PhD MS, Jay C. Butler MD and Philicia Tucker MPH, Oxford University Press (2019). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190056810.003.0002

confluence of drivers that cuts across the health system and societal, legal, and socioeconomic domains has been integral to its progression.

The Evolution of Opioid Use in the United States

Use of opiates (opium and opium derivatives) as a sanctioned intervention for pain relief in the United States dates back to the nation’s founding, when opium was used to treat wounded soldiers of the British and Continental armies during the Revolutionary War. But it was the 1805 isolation of morphine, the active ingredient in the opium poppy, by German pharmacist Friedrich Serturner that truly transformed and expanded its medical use, eventually igniting the beginnings of America’s first opioid epidemic around the time of the Civil War. Initially, morphine was administered in tablet form or applied topically, and then through hypodermic syringes when they were introduced in the 1850s. With few alternatives, and limited understanding of or education on its addictive properties, physicians used morphine extensively to treat a broad spectrum of conditions ranging from asthma to headaches to menstrual cramps.3 In 1874, the British chemist C. R. Alder Wright developed heroin by boiling morphine with acetic anhydride, but it was not until 1897 that Felix Hoffmann, the German chemist who had created aspirin for the Bayer Corporation, developed heroin for introduction for medical use to commercial markets (Figure 2.1). At the time, Bayer marketed heroin as an effective alternative to morphine, particularly for the treatment of children’s colds and coughs. Clinical use of opiates, including morphine and heroin, led many to medical addiction to these drugs and the occurrence of an earlier version of a national opioid addiction epidemic in the United States.

By the turn of the century, clinical use began to slow. Between advances in public health and medicine (including the introduction of aspirin in 1899 and the passage of the federal Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906) and a growing understanding of the addictive properties of morphine and heroin, doctors began to taper their prescription of opiates. In tandem, recreational or “street” use of heroin and opium smoking was growing. In an effort to address both the rise in medically induced dependence and recreational use of opiates, Congress passed the Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914,4 which imposed taxes and regulations on the production, importation, and distribution of opiates and coca-derived products.

By 1924, Congress expanded the Act to ban the importation, sale, or manufacture of heroin, prompting an era of “opiophobia” in the treatment of chronic pain that would persist until late in the 20th century, marked by an inherent tension between a physician’s “desire to relieve the patient’s pain and fear of inducing addiction.”5 Even in the treatment of cancer pain, physicians were extremely wary of administering narcotics, often adhering to the notion that

Figure 2.1. Bayer Corporation—Opium Bottle, c. 1924.

Source: This work has been released into the public domain by its author, Mpv_51. This applies worldwide.

“every effort should be made to put off [their] use until all other measures have been exhausted . . . and the patient’s life can be measured in weeks.”6

Substantially unrelated to the treatment of pain, use and abuse of opiates for the mood-altering effects that had also long promoted their attractiveness took a dramatic jump in the United States during the late 1960s. The combination of new supply sources, soldiers accessing heroin in Vietnam, estranged innercity populations, and counterculture influences all fueled trafficking and use. Because many of the products used in this period were from illicit sources, and the victims of opiate addiction tended to be concentrated in marginalized social strata, the medical treatment system was substantially uninvolved in the response to the patients and public health effects of the problem, and much of the responsibility for managing the challenge fell to law enforcement and social services. As a result, the health care training, treatment, insurance coverage, and supportive services required to address the needs of addicted persons were not developed as a skill and capacity set essential to address the core health needs of millions of Americans.

Then came a shifting focus on pain management. During the 1980s, a number of articles published in prominent medical journals called into question the risk of opioid addiction when opioids were used in the treatment of long-term, non-cancer pain. Most notable is a brief letter published in the

New England Journal of Medicine in January 1980, observing that from the authors’ assessment of records, addiction appeared to be rare among inpatients treated with narcotics with no history of addiction.7 A few years later, in 1986, in a paper evaluating 38 patients treated with opioid analgesics for non-cancer pain, Portenoy and Foley concluded that “opioid maintenance therapy can be a safe, salutary and more humane alternative to the options of surgery or no treatment in those patients with intractable non-malignant pain and no history of drug abuse.”8

Although researchers acknowledged the limits on their rigor and generalizability, the reports of these and selected other papers provided the foundation for a substantial reversal of the accepted narrative for medical treatment of pain, and aggressive commercial marketing of opioids. Treating patients’ pain became the central priority and opioids offered an expeditious, affordable, and seemingly “safe” means for doing so. The tragic casualty of this premature, ill-informed, and unmeasured therapeutic doctrine was a dramatic increase in opioid prescribing and intensive marketing to prescribers, which, in concert with new tactics in illicit opiate trafficking, resulted in an unprecedented opioid addiction epidemic.

Drivers of the Epidemic

Increased opioid use and addiction rates have been driven by multiple factors. Biology is a fundamental driving factor (i.e., the physiologic response systems triggered by exposure to certain substances). As with variation in immune response systems on exposure to allergens, there are myriad variations among individuals in their susceptibilities to the addictive properties of opioids. For a given individual, therefore, the basic starting point driving addictive predisposition is biologic. From that baseline, personal social circumstances and interactions serve to potentiate or buffer against susceptibility to addiction, again with substantial variation from person to person.

The determinants of whether or when a problem progresses from an individual challenge to a society-wide epidemic are systems-based and include the prevalence of the exposure source, knowledge about the agent and the susceptibility profile, the capability of the response system, and societal understanding and will to engage. In the case of opioids, supply was not only unchecked but actively promoted. The health system was unprepared qualitatively and quantitatively, and culturally society’s instinct was to marginalize and moralize the threat, underestimate its reach, underappreciate the science of addiction, and stigmatize individuals experiencing opioid use disorder. Several of these drivers of the epidemic are described in more detail below.