1

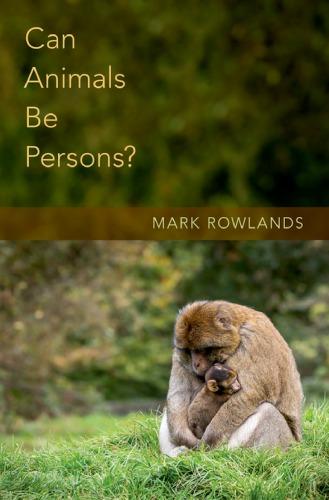

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in India by Oxford University Press 2/11 Ground Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002, India

© Oxford University Press 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

First Edition published in 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

ISBN-13 (printed edition): 978-0-19-948955-8

ISBN-10 (printed edition): 0-19-948955-6

ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-0-19-909535-3

ISBN-10 (eBook): 0-19-909535-3

Typeset in Scala Pro 10/13 by Tranistics Data Technologies, Kolkata 700 091 Printed in India by Rakmo Press, New Delhi 110 020

Acknowledgements

The doctoral dissertation on which this book is based had been long in the making. Part of the reason for this long gestation was the need for a tolerable level of competence in several languages other than Hindi and English. I was very slow to acquire that. It appears to be ages ago when I suggested somewhat hesitantly to Sunil Kumar that I was thinking of working on Vidyapati. The excitement with which he responded made it impossible for me to consider any other topic of research. I was already teaching undergraduate students in the University of Delhi at the time. Little did I know that it would take me a few years and several trips to libraries in Darbhanga, Patna, and even Delhi to collect all the published works of Vidyapati. It took a further few years before I could get leaves sanctioned from my college and focus solely on the project. Staying with a subject for so long had its advantages inasmuch as it allowed me to think and rethink through issues at length. It also allowed my ideas to brew over time. I hope this shows in the book.

I have had the fortune of being in the company of and learning from Sunil Kumar for more than two decades now. He has been my guide, mentor, philosopher, friend, and much more. Had it not been for the faith that he put in me, I would probably have chosen a different career. I have had the fortune of being taught by some of the most competent and inspiring undergraduate teachers before I met him. Yet, it was with his guidance that I started picking up the elementary techniques of research. I do not have the words to express my gratitude for a relationship so enriching as this one.

All through these years, I also received help from numerous colleagues, friends, relatives, and institutions. I do not think I can remember them all. But those that I do, I would like to thank. First of all, I record my gratitude to my debate adviser in high school, R.K. Singh who introduced me to the joys of reading literature. History was too boring for me at the time. When I landed up, by accident, in the history honours programme for my bachelor’s at Ramjas College, the discipline dramatically rose overnight in my esteem. Such was the passion with which Sudhakar Singh taught it in the class. Among my undergraduate teachers, I must also mention Dilip Simeon, whose insistence that history was always political and mostly about the present has stayed with me for good. The brilliant lucidity of Hari Sen’s lectures in the classroom was a source of inspiration.

Fortunately, I got an opportunity to interact with some of the leading scholars in the broad area of my research. Conversations, formal and informal, with them have been a source of questions, ideas, and inspiration. I would particularly like to thank Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Muzaffar Alam, Whitney Cox, Sumit Guha, Daud Ali, Katheryn Hansen, Francesca Orsini, Allison Busch, and Indrani Chatterjee. Among younger scholars and friends, my research has benefitted from conversations with Samira Sheikh, Ravikant, Nilanjan Sarkar, Mayank Kumar, Anubhuti Maurya, and Anand Vivek Taneja.

At Lady Shri Ram College, most of my colleagues were there to help me in times of need. Each member in the Department of History extended their unconditional support to me at all times. I must especially mention Meera Baijal, Vasudha Pande, and Nayana Dasgupta, who have been a source of emotional as well as intellectual support. I also formally note my appreciation for Lady Shri Ram College for

granting me study leave for three years so that I could pursue the PhD programme.

I spent nine months of the study leave at the University of Texas, Austin. I must gratefully acknowledge that my stint at the University of Texas was arranged for and financially supported by the Fulbright–Nehru Doctoral Research Fellowship. I take this opportunity especially to thank Sudarshan Dash and Pratibha Nair of the United States–India Educational Foundation, New Delhi, for their help. Thanks are due also to Zachary Alger of the Institute of International Education, New York, for prompt help on all official issues related to the Fulbright Fellowship during my stay in the USA.

Cynthia Talbot, my research adviser while I was at the University of Texas, was extremely generous with her time, suggestions, and encouragement. She brought very useful readings to my notice and gave invaluable suggestions, especially regarding the way I needed to organize the chapters in my thesis. I express my sincerest gratitude to her.

While I was at the University of Texas, Edeltraud Harzer Clear very kindly allowed me to sit in her Sanskrit classes for the entire semester. I owe my sincerest thanks to her. The staff at the Perry-Castañeda Library, Austin, were invariably prompt in their help. I would particularly like to thank Merry Burlingham, among others.

Gratitude is due also to the library staff of Sahitya Akademi and Indian Council of Historical Research, New Delhi; K.P. Jayaswal Research Institute and Khuda Baksh Library, Patna; and Lalit Narayan Mithila University, Darbhanga.

Among friends, who always stood strongly by me, often in spite of complete disinterest in the precise nature of my work, I must gratefully mention Anil, Baba, Sanjay, Anil Chapoliya aka Sethji, Suman, Sunilji, Topi, and Vijay Singh. Recently, I have also discovered some old friends in new avatars: Rakesh Niraj and Samita among them. My housemate-turned-friend at Austin, Aniruddhan Vasudevan, was one of my most precious finds during my stay in the USA.

Scholars of humanities do not work in laboratories. But for those of us who teach in a university/college, our classrooms are no less than the place where we test our ideas and pick up new ones, frame arguments and hone them. I have had the good fortune of learning from a whole generation of students at Lady Shri Ram College.

My interactions with them have been a singularly enriching experience. I register my gratitude to every student who ever shared an idea with me in the class or asked a question.

My parental family has always been a great source of strength for me. Baby, Ruby, Anmol, and Manoj have been resolute in their affections. My parents-in-law have never been less than indulgent towards me. My stay away from my family for nine months would not have been possible without their support. I express my gratitude to them too. My parents are proud that their son earned a doctoral degree. They are happy that I am publishing a book based on it. I know no one’s satisfaction would be deeper on the mere publication of a book. It is not possible to adequately acknowledge Sneh, my closest friend, companion, spouse, critic, and fellow academic. It was on her insistence that I applied for the Fulbright Fellowship. She took the responsibility of looking after our two rambunctious kids for nine months while I was at Austin. This book is also hers in part. It is indebted to her in a thousand ways and more. I wouldn’t risk belittling all that she has been to me by trying to thank her. My son, Malhar, and my daughter, Tamanna, have been a delightful source of distraction. They duly resented my unending homework. I earnestly hope that my work was worthy also of the time that they rightfully thought was theirs.

About the Author

Pankaj Jha is presently teaching at Lady Shri Ram College, New Delhi, India. He is giving final touches to his English translation of a fifteenthcentury Sanskrit treatise on writing, entitled Likhanāvalī. He is also on the editorial board of the international journal Indian Economic and Social History Review. Earlier, Jha has taught at Ramjas College and St. Stephen’s College, New Delhi.

Jha obtained his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history from Ramjas College, and his MPhil and PhD degrees from the University of Delhi. Part of his doctoral work was done at University of Texas at Austin, U.S.A, on a Fulbright–Nehru fellowship. The primary area of his research interest is the literary cultures of the middle ages. Languages he has worked with include Persian, Sanskrit, Maithili, and Apabhraṃśa. He has published research articles extensively in peer-reviewed journals, in Hindi as well as in English.

Preface

This book is a partially revised version of my PhD thesis submitted to the University of Delhi. My doctoral work had started more than a decade ago with three counts of dissatisfaction with the existing state of historiography in the field normally referred to as ‘medieval India’. The first of these was the fact that the fifteenth century in north India was, with only the rare exception, a barely addressed period. In fact, even these exceptions did not exist at the time when I started thinking about the area of my research. The second point of dissatisfaction issued from the fact that a major chunk of the historiography of this period in North India appeared to have become synonymous with Persian studies. The ‘mainstream’ histories of ‘medieval’ North India rarely bothered to consult the large corpus of extant materials in Sanskrit, thus catering lazily to the popular and hugely problematic equation of medieval = Persian = Muslim = foreign. The third point had to do with the disappearance of the regions falling in the present province of Bihar from ‘histories

of medieval India’. This absence was especially hurtful as I spent the first seventeen years of my life in Jamshedpur, a part of the then undivided Bihar. Under the circumstances, a close study of some of Vidyapati’s works came in very handy, since he was a Sanskrit scholar and poet of the fifteenth century, who spent most of his life in north Bihar. Since the inception of my work, there has been some exciting new work in the area, and I discuss some of it in the second chapter of the book. This book, I hope, will add further force to the gathering momentum.

At a time when we are exhorted 24 × 7 to understand politics as the game played by those who occupy the offices of the state and those who aspire to replace them, it is important to recover a slice of history when intellectual ferment, dissemination of ideas, ethical regimes, and cultivation of certain skills, such as those of documentation, seem to have had substantive political consequence in the long term. While this is probably true of all times, it is more starkly visible in a period during which readymade histories and master-narratives of imperial formations were not produced. North India in the ‘long fifteenth century’ is a case in point when we do have this unusual silence.

When I made the fateful journey from a humble Hindi-medium school to Ramjas College, Delhi, it was a huge task to cope with the heat, dust, English language, and cultural alienation in a metropolitan city. Unfortunately, neither of the two factors that helped me survive and grow in spite of the material hostilities has survived. It was the ‘leisurely’ pace of the annual system that allowed ‘slow-wits’ like me to adjust to the demands of the academic rigours of University of Delhi. Come 2010, and that leveller of the academic field was forced to give way to a ruthless system of six-monthly examinations and continuous assessment, with no space to make mistakes and learn on the go.

One of my first companions in the college campus, hardier and more sincere than most of us, was Rakesh. His raw humility, desi humour, extraordinary generosity, and candid affections steadied many wayward souls like myself. He is no more. He would have taken personal pride in this book. I dedicate it to his memory.

Pankaj Jha

September 2018 Delhi

Tables, Images, and Figure

4.1

1.3b

Notes on Transliteration

All translations from Sanskrit, Apabhraṃśa, and Hindi are mine, unless otherwise specified. In the case of Persian, I have indicated in the footnotes where I have consulted the original and where I am using translation(s) by others.

All non-English words have been italicized except those that occur too frequently. I have not used diacritics for place-names that are still in official or/and popular use. However, the older variants of the same have been marked with diacritics. Thus, I refer to the village of Vidyapati’s birth, which is still there in north Bihar, as Bisfi. However, its old name is referred not as Bispi but as Bisapī.

All dates in the book are in the Common Era (ce) unless otherwise specified.

For Persian words, no diacritics have been used, partly in order to avoid possible confusion between the standard methods of transcribing Persian words into English and those for transcribing Sanskrit words into English. Hence, while rendering the Persian words into

English, only readability has been kept in mind, which often led me to adopt the most commonly used spellings.

The transliteration scheme followed for Sanskrit, Apabhraṃśa, Hindi, and Maithili words are given below: अ a आ ā

tha

pa

Introduction

This book has been conceived as a political history of literature in the fifteenth century. It is neither an exhaustive consideration of all literature produced in that age in North India, nor does it claim to be a treatment of a ‘representative’ sample of all such compositions. Rather, I have focussed on three sharply different texts of a prolific poet, Vidyapati, from an atypical region, Mithila. I have tried to use the three texts under consideration to open up the wider world of literature in the fifteenth century. Thus, I relate Vidyapati’s compositions to the existing traditions of literary production of the time, with a view to unearth the deeper histories that lay behind them. Given the state of the relevant historiography, this was a huge methodological challenge.

The book is organized in five chapters, which are unevenly divided in two parts, preceded by a short introduction, and followed by a conclusion. The conclusion ties up the points made by the different chapters both at a general, methodological level, as well as in the

APoliticalHistoryofLiterature:VidyapatiandtheFifteenthCentury. Pankaj Jha, Oxford University Press (2019). © Pankaj Jha. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780199489558.001.0001

specific context of the long fifteenth century, in a way that might connect its details with certain larger questions of contemporary as well as historical significance.

The first part of the book has two chapters: the first provides basic information about Vidyapati, his compositions, and his immediate geopolitical and intellectual milieu. The second chapter takes critical stock of the more dominant and recent strands of historiography of the ‘long’ fifteenth century. But it also uses this critical stock-taking as a step towards (a) broadly mapping the literary cultures of the fifteenth century, and (b) thinking about issues of historical method, historians’ possible engagements with literature, knowledge formations, and power, as a set of related themes. The second part of the book has three chapters, each centred around, but not limited to, one of the texts of Vidyapati, namely, Likhanāvalī, Puruṣaparīkṣā, and Kīrttilatā, out of more than a dozen of his compositions available in print whose authorship is not disputed. While I do refer to the poet’s other compositions whenever the context requires me to, these are not taken up for detailed exploration.

Before I move to the next section, let me put in an explanation for why I treat Mithila as an ‘atypical’ region. The ‘region’ of Mithila was atypical in two distinct ways. First, at a moment when a robust system of long-distance trade had developed in most parts of the subcontinent, Mithila lay on none of the major trade routes of the time. Second, for related reasons, Mithila continued to survive as either an independent chieftaincy or as a semi-autonomous principality of the three major sultanates of the long fifteenth century in its neighbourhood: Delhi, Jaunpur, and Bengal. It was only in the mid-sixteenth century that it emerged as an integral and separate territorial unit of a major imperial power, namely, the Mughal state. As such, it figures only marginally in the standard narratives of the Delhi Sultanate or the other sultanates up to the first half of the sixteenth century.

Why Vidyapati?

When I started researching the enormous corpus of literature left behind by Vidyapati, all I knew was that I wanted to focus on non-Persian textual productions of the fifteenth century. Medieval

historiography has hitherto shown little patience with the fifteenth century, and precious little interest in non-Persian ‘sources’. Vidyapati, however, was doubly attractive because he was multilingual and lived in Mithila, an area that modern historians, like most Persian chroniclers of the middle ages, often passed by quietly. And yet, Vidyapati’s literary corpus was vast, disparate, and straddled a range of what appeared to be unconnected worlds. There was law, love, writing, political ethics, biography, rituals, tantricism, ‘geography’, romantic play, ritual donations (dāna), and a vast corpus of songs for a variety of occasions. My problem was to focus on specific issues, and accordingly on certain texts, so I could study the author and his oeuvre more intimately.

After weighing in all my options, I decided to focus on the following three of Vidyapati’s compositions. Kīrttilatā was a text I could not have avoided for the simple reason that it was the only major extant work of Vidyapati that was composed in Apabhra ṃ śa. Since one of my concerns was to examine the relationship between language, literature, and politics, this explicitly political text—a biopolitical narrative in ‘vernacular’ with a local prince as its protagonist—suggested itself ‘naturally’. Puruṣaparīkṣā was another work that appeared unique in the history of Indic literatures, being possibly the only known early modern text that so directly propounded what might be termed a theory of masculinity. That it was simultaneously a work on naya / da ṇḍ anīti , or political ethics/ state policy, also suited my proposed engagement with issues of literature and state formation, or more generally, knowledge and power. No less compelling for me was the choice of Likhanāvalī , again for the simple reason that it was possibly the first text of its kind in Sanskrit. Being so centrally concerned with the state, this work too could add variety to my investigation of matters related to another ‘literary’ dimension of state power, namely, documentation. As I hope to demonstrate in the third chapter, however, Likhanāvalī turned out to be much more than what it claimed, a manual for those interested in cultivating the craft of documentation. A first-ofits-kind Sanskrit text that borrowed imaginatively from a range of literary traditions including Persian, it provides a glimpse into the eclectically constituted ways of making literature and imagining imperium in the fifteenth century.

If I mention the process by which I arrived at my choice of these compositions, it is because they are not in any way meant to be ‘representative’ works of Vidyapati. It would be virtually impossible to make such a list for an author as varied in his choice of subjects as the scholar from Mithila. What was important about my choice of the three texts was the way in which they treated the issues I wanted to explore, each in its own distinctive way. From the point of view of genre, or language and literary strategies, they represent very divergent authorial exercises. This allowed me the opportunity to explore afresh how a historian’s literary engagement with her/his ‘source texts’ was crucial for a nuanced reading.

The argument that the centuries after the thirteenth in North India were fast turning out to be riotously multilingual in literary practice and everyday speech is much more convincing today than it was ten years ago. Equally strong is the case now for this period being diverse and dynamic in its literary themes, genres, and sheer volume.1 In several ways, Vidyapati seems to embody the spirit of the long fifteenth century more substantively than any other literary figure of the time. He wrote in at least four languages, and probably knew a few more. If many before him wrote vernacular verses in a style that celebrated ‘male’ heroism, he too did that; if the fifteenth century was the period of the so-called bhakti movement, he represented one of the most irresistible voices of that trend; if the dharmaśāstras continued to be important, he too wrote one; if tantric cults were gaining popularity, he wrote a play with one of the most prominent protagonists of tantricism as its hero; and he was surely not the only Brāhmaṇa scholar of the period who drew patronage from a host of minor princes of more than one royal household. He composed in a dozen genres including some that he almost invented himself; he lived in a local chieftaincy that seemed to be farthest from big imperial formations. I do not, however, claim to study Vidyapati as any sort of a ‘representative’ of the fifteenth century. Rather, I use his compositions to reach out to other related ones, and eventually to open up the times he lived in.

1 For a detailed argument of the case, see Jha, ‘Literary Conduits for “Consent”’. Also see Orsini and Sheikh, ‘Introduction’.

Political History of Literature or a Question of Method

For long, historians have believed that it is important to study an author before one studies his/her work. It is equally important, however, to explore the implications of an author’s choice of language and of genre. In choosing to compose in a language, authors chose a certain readership/audience, along with a whole system of idioms constituted culturally. In doing so, they might, as indeed Vidyapati did, simultaneously expand (or narrow down) the horizons of that language in multiple ways. The manner in which it would be read/ recited and the usage to which their authors hoped their texts would be put also depended largely on the choice of language and register. A composition could be used for performative purposes, for public recitations, for popular retelling, or for quiet and private study by peers. Equally, in choosing a genre, authors chose to be bound by the conventions of that genre, whether flexibly or strictly. The content of the compositions would tend to reflect the authors’ concerns and issues. But the authors would often also feel obliged to speak to, and speak in, the voice of past authors in the chosen genre.

My attempt, however, is to relate this literary corpus to ‘mainstream’ history, and attempt a political history of literature. How does one contextualize internally coherent and apparently monolingual texts like Likhanāvalī, Puruṣaparīkṣā, and Kīrttilatā in a milieu that was so pervasively multilingual? I trace the parallel and comparable developments elsewhere in North India during the time, while diachronically excavating the deep histories and multilingual debts of apparently monolingual texts.

Locating the texts within the long-term patterns of development of languages and literature in North India could only be one aspect, a first step towards writing a political history of literature. This first step involves, among other things, looking carefully for tangible traces of intertextuality in them, but also for the not-so-tangible (often unacknowledged) signs of ‘influences’ from other languages and genres. It is well established, if seldom realized by historians, that texts on a theme become intelligible only to the extent that they are part of ongoing streams of conversation with other texts on that theme. Even the novelty of a literary composition lies in its ability to adapt, respond to, or rebut already existing propositions in other texts. The ‘originality’

quotient of a new work may also lie in its response to changes ‘outside’ the text, say, in material conditions of life or changes in political culture. Even when the poetic imagination breaks ‘fresh’ ground by articulating an aspiration or conjuring up fantastic images, the use of familiar terminologies can hardly be avoided. That is why I find it useful to historicize the texts, and determine the nature and variety of streams that feed into them.

For long, historians treated literature like enemy territory. Their standard modus operandi was to conduct surgical strikes on texts to extract ‘history’ (read ‘facts’ and suggestive pieces of information) from them. This fundamentally violent approach bypasses the literariness of a composition that one cannot access without placing it within its own textual tradition. My explorations suggest that emplacement of an imaginative work within the deep histories of its own language–genre–theme tradition makes the work reveal much more than pieces of information. Such an approach helps us locate those aspects, which are unique to the text, as well as identify alternative ideas, which the text might have been responding to. After all, a literary expression is also, among other things, an intervention in the dynamic flow of history: a wager in an ongoing conversation—real or imagined.

This requires historians engaging with their ‘sources’, irrespective of what aspects she/he is looking into, to look deep and wide into other texts so as to see the work at hand itself as a historical product. Within a multilingual literary culture, this is a very difficult task. It requires us to look for relevant practices in several languages simultaneously.

And this leads to the second step in my reading of Vidyapati. If the first step helps me find out ‘where the texts are coming from’, the second step involves the issue of ‘where they are going’. The question that I put across is this: what kind of socio-political order did these texts uphold? What visions of power did they describe, proscribe, or prescribe? To put the question prospectively, what political possibilities could the literary cultures of Mithila prepare the ground for?

As far as medieval studies are concerned, this was a bit of a leap in the dark. Typically, premodern historians relate literature (as also other cultural products) to politics by looking at patterns of patronage, and immediately hitting the dead end of (often instant) legitimation. This approach sees culture as a by-product of politics and (more often

than not, state) power.2 I discuss the limitations of this approach in the second chapter. I do not, however, imply ‘literary determinism of political action’.3 Nor do I assign, as Sheldon Pollock does, an ‘autonomous aesthetic imperative’ to literary initiative.4

Methodologically, there are four interrelated components to my approach to literature: first, I treat literary compositions as historical products, and seek to trace their antecedents not in an isolated history of ideas but in the cultural politics of the past and (the then) present; second, I keep the possibility alive that an author’s location in a small or ‘local’ principality might not be the sole or even the major determinant of her/his political vision; third, that in a place where there was no established institutionalized space (unlike, say, the church in Europe) for regular communication with people, literature, especially its durable forms (for example, stories and poetry that could be remembered and related more easily) in a largely oral culture, would play an extremely important role in enunciating the terms of cultural discourse. Finally, I ask the simple but perhaps the most important question of all: what is the political value of literature? Alas, historians (unlike philosophers!) can never hope to answer that question once and for all. I pursue the question, fully cognizant of the fact that the meaning of ‘political’, very much like the character of literature, is historically variable. One can map the complex relationship between the two only in the long duration. I briefly discuss the dynamics of this relationship in the later part of Chapter 2 in this volume.

2 There are occasional exceptions though. In a study of the oeuvre of the famous Telugu poet Ṣrīnātha and the Telugu literary traditions in the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries, for example, Velcheru Narayana Rao and David Shulman offer the opposite view. They note that in an ‘unstable and fragmented political climate’, ‘the patron and the poet were locked in a relation of asymmetrical dependence—the former being essentially dependent upon the good grace and poetic talent of the latter, who nevertheless needs the patron for his economic survival’. See Rao and Shulman, Śrīnātha, p. 6.

3 I have borrowed the phrase from Jene Andrew Jarrett. See Jarrett, Representing the Race, p. 7.

4 Pollock, ‘India in the Vernacular Millenium: Literary Culture and Polity’, p. 44.

In this endeavour, my debt to Sheldon Pollock should be obvious. The excitement generated by his study of the literary cultures of Sanskrit and other Indic languages has refused to subside, even two decades after he first proposed a millennium-by-millennium binary paradigm of Sanskrit cosmopolitanism and vernacularization. If excessive focus on Persian ‘authorities’ was my problem with medieval studies, here was a scholar whose engagements with nonPersian literature and literary cultures of the middle ages marked out a ‘parallel’ archive. It was a massive archive, replete with all possible genres, and tantalizingly diverse in its themes, locations, and patronage patterns.

Paradoxically, however, if the ‘mainstream’ historians of medieval India had, to a large extent, failed to account for the massive presence of Sanskrit and vernacular sources, Pollock’s engagements with this archive reduced the Persian ecumene along with the Delhi Sultanate, Mughal state, and other ‘regional’ states (seen to be exclusively) invested in Persian culture to minor footnotes. If the claims of Persian chroniclers enjoyed a positivistic salience in the historiography of the Sultanate and Mughal state, Pollock and his adherents too, followed the same methodological track: Sanskrit was reported dead on arrival (or localized) by the second millennium; vernacularization of politics reigned sway in complete innocence of the presence of Persianized conceptions of imperium; and monopolistic truth-claims of the language of the gods passed uncritically into histories of literary cultures.

Ironically, these two neat archives (Sanskritistic and Persianate), corresponding broadly to two parallel historiographies, fell into the same isolated territories of investigation that Pollock, trained in Sanskrit philology, himself had warned against: ‘What the theorists [and presumably historians] say about us, “all dressed up and nowhere to go,” hits a lot harder than what we say about them: “lots of dates and nothing to wear”’.5

My work, however, is humbler in scope, and I would like to believe, more historicized in method. That is why, instead of bunching texts together in hundreds and ticking them off as monolingual/bilingual

5 Pollock, ‘Future Philology?’, p. 947.

and local/universal, I focus ‘only’ on three texts. This allows me to carefully examine the framing, language, literary techniques, content, genre, and genealogy of each. In the process, many inherited categories that one was used to taking for granted proved to be miserably inadequate (or in need of modification) to describe the worlds of complexity that these texts revealed. Thus, for example, my examination of Puruṣaparīkṣā shows that the text deployed narratives of recent history in novel ways to justify ethics that are simultaneously validated with reference to Vedic lore. The entirely modern distinctions between secular and religious appeared inadequate.

The evidently multiple forms of multilingual literary cultures in the fifteenth century—lexical, generic, idiomatic, thematic, authorial, among others—at one level are interesting in themselves. Yet, the follow-up questions are equally important: what kinds of power relations did the textual productions of the time try to uphold? What sorts of future political enterprises could this kind of literary culture prepare the ground for? To put the question in a simplistic and linear sequence, if literatures created/disseminated ‘knowledge’, and if knowledge formations are bedrocks on which fields of power are laid and exploited, then what could all this mean politically beyond the actual existing polities, in the long term?

As a prelude to answering that question, I also pose, in Chapter 2 in this volume, the intermediate theoretical problematic of what the categories of literature, history, and power mean to a historian now (in the ‘emic’ sense), and what they could have meant to someone in the fifteenth century following various literary traditions (in the ‘etic’ sense). My exploration of each of the three texts in the second part is also an empirical way of opening up these larger theoretical questions. These apparently theoretical engagements are crucial for reconstituting the space for a political history of literatures and languages.

In the end, it is of critical significance for me to clarify that while trying to work out the contours of a knowledge formation by mapping the literary culture of the long fifteenth century, I am making assumptions about a slow-moving but tangible relationship between literature and knowledge formation on the one hand, and power and political possibilities on the other. In this analysis, however, I make a clear distinction between relations of power and institutions of governance. Governance is a tangible, everyday practice, undertaken

by particular institutions like family, caste-bodies, guilds, and above all, the state. These and other institutions governed subjects as per written and unwritten codes of law, ethics, morality, and tradition. However, I use the word ‘power’ primarily as a disciplining mechanism through discourses about ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’, moral and immoral, or acceptable and non-acceptable. It is this disciplining wiring of society that a new dynamism of literary culture could enter and alter. And it is this slow process of changes in disciplinary formations that I seek to unravel.

While institutions of governance surely need to be studied, my interest in this volume is limited to a study of the ways in which the basis for changes in power relations was being laid in the fifteenth century, without any individual or institution having willed consciously to do so: Particular kinds of stories being told in specific ways, for example, could play an important role in spreading and reconstituting knowledge formations. To the extent that I succeed in doing this by exploring literary productions of the time, I will have succeeded in highlighting the political value of literature.