About the Authors

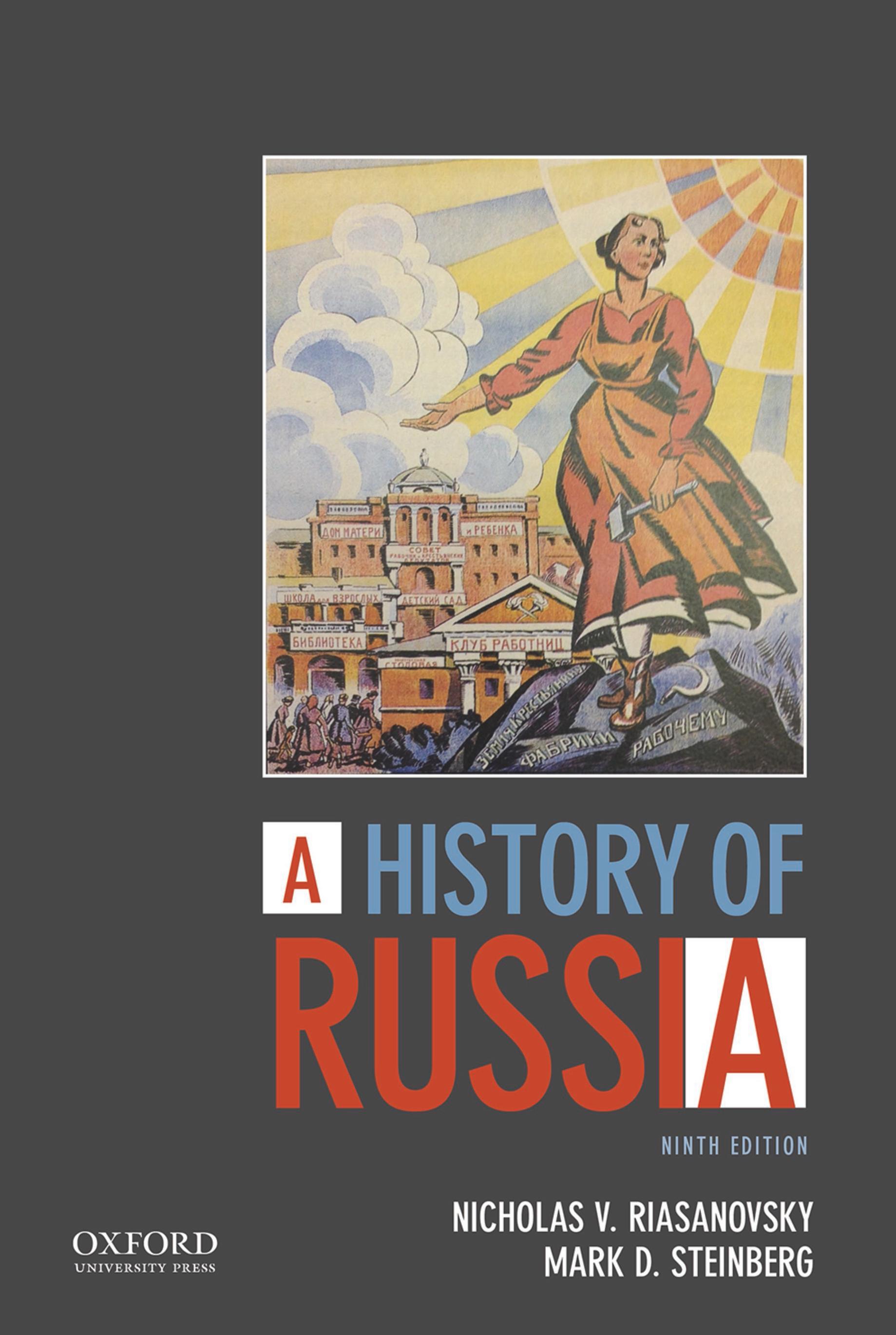

Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, born in Harbin, Manchuria, in 1923 and educated in Oregon and Oxford, was among the most prominent historians of Russia in the world. In 1957, he joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley, where he worked for the rest of his career. His honors include election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1987. Riasanovsky’s many influential books, in addition to A History of Russia, include Nicholas I and Official Nationality in Russia, 1825–1855 (University of California Press, 1959); A Parting of Ways: Government and the Educated Public in Russia, 1801–1855 (Oxford University Press, 1976); The Image of Peter the Great in Russian History and Thought (Oxford University Press, 1985); and Russian Identities: A Historical Survey (Oxford University Press, 2005). He passed away in 2011.

Mark D. Steinberg was born in San Francisco, California, in 1953 and received his Ph.D. from University of California, Berkeley in 1987 and has been a professor of history at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign since 1996, after previously teaching at Oregon, Harvard, and Yale. Riasanovsky invited him in 2002 to become co-author of A History of Russia, beginning with the seventh edition Steinberg’s books include The Fall of the Romanovs: Political Dreams and Personal Struggles in a Time of Revolution (Yale University Press, 1995), Voices of Revolution, 1917 (Yale University Press, 2001), Proletarian Imagination: Self, Modernity, and the Sacred in Russia, 1910–1925 (Cornell University Press, 2002), Petersburg Fin-de-Siècle (Yale University Press, 2011), The Russian Revolution, 1905–1921 (Oxford University Press, 2016), and edited collections on popular culture, religion, and emotions. From 2006 to 2013, he was editor of the interdisciplinary journal Slavic Review. In 2017, he was elected vice-president and president-elect of the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies.

His scholarly honors include grants from Fulbright, the Social Science Research Council, the National Endowment of the Humanities, the International Research and Exchanges Board, and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

Maps x Illustrations xii

New to the Ninth Edition xvii

Preface to the Ninth Edition xviii

Part I KIEVAN RUS

1 Introduction: The Lands and Peoples of the Eurasian Plain 3

2 A Political Outline, c. 882–1240 10

3 Institutions, Economy, Society 24 4 Religion and Culture 32

Part II APPANAGE RUSSIA

5 Appanage Russia: Introduction 43

Mongol Rule 47 7 Lord Novgorod the Great 54

The Southwest and the Northeast 64

The Rise of Moscow 70

Institutions, Economy, Society 85

Religion and Culture 93 12 Lithuania, Poland, and Russia 105

Part III MUSCOVITE RUSSIA

13 Ivan the Terrible, 1533–84 113

The Time of Troubles 128

15 The Early Romanovs, 1613–82 145

16 Institutions, Economy, Society 156

17 Religion and Culture 167

Part IV IMPERIAL RUSSIA

18 Peter the Great, 1682–1725 185

19 From Peter the Great to Catherine the Great, 1725–1762: Catherine I, Peter II, Anne, Ivan VI, Elizabeth, and Peter III 210

20 Catherine the Great, 1762–96, and Paul, 1796–1801 222

21 E conomy and Society in the Eighteenth Century 242

22 Russian Culture in the Eighteenth Century 250

23 A lexander I, 1801–25 265

24 Nicholas I, 1825–55 285

25 E conomy and Society before the Great Reforms 301

26 Russian Culture in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century 309

27 Alexander II, 1855–81 326

28 Alexander III, 1881–94, and Nicholas II to the Revolution of 1905 348

29 Nicholas II in the Era of Revolution and Reform, 1905–17 363

30 Economy and Society from the Great Reforms to 1917 383

31 Russian Culture from the Great Reforms to the Revolutions of 1917 400

32 The Revolutions of 1917 423

Part V SOVIET RUSSIA

33 Revolutionary Russia, 1917–28 439

34 The Stalin Revolution, 1928–39 465

35 The Soviet Union and the World, 1921–45 482

36 Stalin’s Last Years, 1945–53 501

37 Politics and Economy after Stalin, 1953–85 511

38 Soviet Society, 1917–85 535

39 S oviet Culture, 1917–85 552

40 Glasnost, Perestroika, and the End of the Soviet Union, 1985–91 566

Part VI RUSSIAN FEDERATION

41 Politics after Communism: Yeltsin and Putin 587

42 E conomy, Society, and Culture after Communism 626

Appendix: Russian Rulers A-1

Bibliography: Select Readings in English B-1

Index I-1

Maps

1. Early Migrations 8

2. K ievan Rus in the Eleventh Century 17

3. Appanage Russia from 1240 44

4. Mongols in Europe, 1223–1380; Mongols in Asia at Death of Kublai Khan, 1294 48

5 Lord Novgorod the Great Fifteenth Century 55

6. Volynia-Galicia, c. 1250 65

7 Rostov-Suzdal, c. 1200 67

8. R ise of Moscow, 1300–1533 72

9 T he Lithuanian-Russian State after c. 1300 106

10. Russia at the Time of Ivan IV, 1533–1598 115

11. T he Time of Troubles, 1598–1613 131

12. Expansion in the Seventeenth Century 152

13. Europe at the Time of Peter the Great 1694–1725 187

14. Central and Eastern Europe at the Close of the Eighteenth Century 223

15. Poland 1662–67 and Partitions of Poland 237

16. Central Europe, 1803 and 1812 276

17. Europe, 1801–55 280

18. T he Crimean War, 1854–55 298

19. T he Balkans, 1877–78 344

20. Russo-Japanese War, 1904–5 360

21. Russia in the First World War–1914 to the Revolution of 1917 380

22. Revolution and Civil War in European Russia, 1917–22 448

23. Russia in the Second World War, 1939–45 491

24. I ndependent States of the Former Soviet Union 584

25. Contemporary Russia 592

26. T he Evolution of the Lands of Ukraine through History 616–617

Illustrations

1. Scythian goldwork of the sixth century B.C. (Hermitage Museum). 7

2. Building Kiev (University of Illinois Library). 30

3. Head of St. Peter of Alexandria (Sovfoto). 38

4 Cathedral of St. Dmitrii (Mrs. Henry Shapiro). 39

5. S eal of Ivan III (Armory of the Kremlin, Moscow). 80

6 Cathedral of the Assumption, Moscow Kremlin (Mark Steinberg). 101

7. T he Holy Trinity by Rublev (Tretiakov Gallery, Sovfoto). 102

8. Ivan the Terrible (Sovfoto). 121

9. False Dmitrii (Tsarstvuiushchii dom Romanovykh [St. Petersburg: n. p., 1913]). 133

10. Zemskii sobor elects Michael Romanov (Tsarstvuiushchii dom Romanovykh). 141

11. Tsar Alexis (Tsarstvuiushchii dom Romanovykh). 148

12. Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky (engraving by Willem Hondius, 1598–1652) 154

13. Patriarch Nikon (Ukrainskaia portretnaia zhivopis’ XVII–XVIII vv [Leningrad: Iskusstvo, 1981]). 171

14. St. Basil’s Cathedral, Moscow (Adam Olearius, The voyages & travells of the ambassadors sent by Frederick, duke of Holstein, to the great Duke of Muscovy and the King of Persia [London, 1662]). 179

15. Nemetskaia Sloboda (M. A. Alekseeva, Graviura Petrovskogo vremeni [Leningrad: Iskusstvo, 1990]). 181

16. Peter the Great as a warrior (Sovfoto). 188

17. Peter the Great on a map of Europe (Alekseeva, Graviura Petrovskogo vremeni). 198

18. El izabeth (Tsarstvuiushchii dom Romanovykh). 215

19. Peter III (A. G. Brikner [Brückner], Illiustrirovannaia istoriia Ekateriny vtoroi [St. Petersburg: Suvorin, 1885]). 217

20. Catherine II in 1762 (Brikner, Illiustrirovannaia istoriia Ekateriny vtoroi). 225

21. Pugachev (Brikner, Illiustrirovannaia istoriia Ekateriny vtoroi). 229

22. “Allegory of Mathematics,” 1703 (Alekseeva, Graviura Petrovskogo vremeni). 252

23. Ni kolai Novikov (Brikner, Illiustrirovannaia istoriia Ekateriny vtoroi). 262

24. Alexander I (Tsarstvuiushchii dom Romanovyh). 266

25. Coronation Medal of Alexander I (Tsarstvuiushchii dom Romanovykh). 269

26. Nicholas I (Tsarstvyuiushchii dom Romanovykh). 286

27. Alexander Pushkin (New York Public Library). 315

28. Vissarion Belinsky (lithograph by Kiril Gorbunov, 1843) 324

29. Alexander II (Tsarstvuiushchii dom Romanovykh). 327

30 Peter Valuev, Minister of the Interior, balancing between “yes” and “no.” From the satirical magazine Iskra, 1862 (no. 32). 337

31. Alexander III in 1889 (Treasures of Russia Exhibition). 350

32. Nicholas II in seventeenth-century costume, 1903 (New York Public Library). 354

33. Nicholas II blessing troops leaving for the front in the Russo-Japanese War, 1905 (Sunset of the Romanov Dynasty [Moscow: Terra Publishers, 1992]). 358

34. Social Democrats demonstrate in 1905 (Russian State Archive of Film and Photographic Documents). 367

35. Petr Stolypin (Central State Archive of Film, Photographic, and Sound Documents of St. Petersburg). 373

36. Grigorii Rasputin (Rene Fülöp-Miller, Rasputin: The Holy Devil [Leipzig: Grethlein and Co, 1927]). 382

37. A meeting of the mir (Victoria and Albert Museum). 387

38. Count Sergei Witte in St. Petersburg in 1905 (Sunset of the Romanov Dynasty). 391

39. Alexei Medvedev (Moskovskie pechatniki v 1905 godu [Moscow: Izd. Moskovskogo gubotdela, 1925]). 394

40. T he Passazh on Nevsky prospect, 1901 (Central State Archive of Film, Photographic, and Sound Documents, St. Petersburg). 397

41. Fedor Dostoevsky (New York Public Library). 405

42. Lev Tolstoy (New York Public Library). 407

43. A nna Akhmatova (Zephyr Press, Brookline, MA). 411

44. Vaslav Nijinsky (New York Public Library). 414

45. Kazimir Malevich, “0.10: Last Futurist Painting Exhibition,” Petrograd, 1915 (Mark Steinberg). 415

46. Provisional Government (Russian State Archive of Film and Photographic Documents). 427

47. V. I. Lenin in 1917 (Vladimir Il’ich Lenin: Biografiia [Moscow: Gosizdat, 1960]). 432

48. Soldiers at funeral for fallen in revolution (Russian State Archive of Film and Photographic Documents). 434

49. “A Specter Is Haunting Europe—the Specter of Communism” (Victoria Bonnell). 441

50. “The Struggle of the Red Knight against the Dark Force,” 1919 (Gosizdat). 449

51. Nikolai Bukharin (Stephen Cohen). 461

52. Lev Trotsky (New York Public Library). 462

53. Iosif Stalin (Sovfoto). 463

54. “Full Speed Ahead with Shock Tempo: The Five-Year Plan in Four Years,” 1930 (Lenizogiz). 470

55. “Long Live Our Happy Socialist Motherland. Long Live Our Beloved Great Stalin,” 1935 (Victoria Bonnell). 473

56. Soviet Communist Party and “deviationists” (Mark Steinberg). 477

57. “Any Peasant . . . Can Now Live Like a Human Being,” 1934 (Victoria Bonnell). 480

58. “Avenge Us!” 1942 (Sovetskoe iskusstvo). 499

59. “Under the Leadership of the Great Stalin,” 1951 (Victoria Bonnell). 505

60. Stalin’s funeral (Sovfoto). 512

61. Nikita Khrushchev (Sovfoto). 515

62. Soviet leaders, 1967 (World Wide Photos). 518

63. Brezhnev on a skimobile (V. Musaelyan). 520

64. Kustodiev, “Bond between City and Country,” 1925 (Gosizdat). 538

65. “What the October Revolution Gave the Woman Worker and the Peasant Woman” (1920) (Victoria Bonnell). 544

66. Young women on a Moscow street in the 1980s (I. Moukhin). 547

67. Literacy poster, 1920 (Gosizdat). 554

68. V ladimir Tatlin, Monument to the Third International, 1919–20 (Nikolai Punin, Pamiatnik III Internatsionala [Petrograd: Otd. izobrazitel’nykh iskusstv N. K. P., 1920]). 561

69. Moscow State University (World Wide Photos). 562

70. Leaders of the communist world, 1986 (World Wide Photos). 569

71. “We shall look at things realistically” (Sovetskii khudozhnik). 571

72. Patriarch Alexis II blessing Yeltsin (World Wide Photos). 577

73. A young woman sits on a toppled statue of Lenin in Lithuania following the failed Kremlin coup, August 1991 (AFP/Getty Images). 583

74. Boris Yeltsin on tank in August 1991 (Associated Press). 590

75. V ladimir Putin speaking with American journalists, 2001 (Alexander Zemlianichenko, Associated Press). 604

76. President Putin hunting. (Dmitry Astakhov/AFP/Getty Images) 610

77. Demonstration against prikhvatizatsiia, Moscow 1992 (Mark Steinberg). 629

78. Sales booth in Moscow, 1994 (Mark Steinberg). 631

79. Small business in Moscow, 1994 (Mark Steinberg). 631

80. Poverty and wealth 2007 (Maxim Marmur/AFP/Getty Images). 632

81. Communists demonstrate in Moscow, 1992 (P. Gorshkov). 639

82. Pussy Riot, 2012 (ITAR-TASS Photo Agency/Alamy Stock Photo) 644

83. Woman in church under reconstruction, 1991 (M. Rogozin). 646

84. Christ the Savior cathedral in Moscow being rebuilt, 1997 (Mark Steinberg). 648

85. S ex and Violence, 2000 (Izd. “Eksmo”). 651

86. Viacheslav Mikhailov, “Metaphysical Icon,” 1994 (V. Mikhailov). 655

Preface to the Ninth Edition

The ninth edition of A History of Russia has been very extensively revised. The seventh edition, the first with my participation, saw considerable change in certain areas, especially revisions reflecting new research on the late-imperial and Soviet eras and expanded coverage of the postcommunist years. The eighth addition, which appeared the year that Nicholas Riasanovsky passed away, included some revisions of the narrative and interpretation before 1855 and additional updates of the late imperial, Soviet, and post-Soviet eras.

This ninth edition has been revised with the same goals as before: to reflect new research, new questions, and new interpretations. In particular, I have expanded attention to the experiences and voices of less privileged groups, to women in all classes (and the question of gender), and to non-Russians (and the question of empire). Indeed, I have made the history of imperial expansion and diversity much more central to the history of Russia. I have again updated the h istory of Russia after communism, especially the era of Putin. Finally, I have shortened the length of the book by tightening some of the more detailed descriptions.

Frankly, it is a weighty responsibility to be continuing the work of Nicholas Riasanovsky, who devoted more than half a century of hard and careful work to successive editions of A History of Russia. I am very cognizant of the strength of his approach, amid all the changing fashions of historiographical method: careful attention to documentable facts, recognition of conflicting and changing interpretations, every attempt to ensure balance and fairness, and an inclusive and complex view of history that attends not only to the actions of rulers but also to political ideologies, economics, social relations, intellectual history, culture, and the arts. I try to hold on to these principles as I revise his magisterial but never stagnant text.

The task of the historian, Riasanovsky believed, is to work both with and against one’s beliefs, in the pursuit of care, balance, and fairness. In an oral history interview in 1996, he remarked that “My father [a noted Russian academic himself], who knew various groups of people, said by far the best people—balanced, judicious, extremely careful in what they do—were judges, not professors.” The son, like the father, tried to follow this judicial approach in his own work. In this light, he titled his book “A History of Russia” not “The

History of Russia.” The reason he wanted the book to be continually revised is because he knew that once it stopped questioning its own account with new information and interpretations the text would begin to die.

In his 1996 interview, Riasanovsky observed that “history is everything,” and A History of Russia has from the first aimed for exceptional comprehensiveness, including poetry and painting alongside wars and laws, political events but also social and economic structures, official policies along with currents of social and cultural thought—and how these all might connect. I should not have been surprised, therefore, when he readily agreed with my suggestions that we do more to develop newer themes and points of view—more social history, especially the experiences of workers and peasants, more on women and gender, more on non-Russians and empire, more on popular culture. I bring my own preoccupations as a historian to this text, especially “history from below” and history focused on diverse human “experience”— ideas, expectations, and emotions in relation to material and lived realities. But I have found that these fit very well with Riasanovsky’s attachment to facts, fairness, balance, and breadth.

Riasanovsky could be wonderfully eloquent and witty, especially in person (he loved to tell jokes) but also as a writer. I have tried to preserve these moments in the text. I will never be as erudite or well-rounded a historian as he was, so I have tried to keep his voice strong here. I have made a great many changes, some of which he might not agree with. Originally, I mailed these to him and we talked over every change by telephone. He was always a generous co-author but also had a sharp critical mind and a vast wealth of knowledge. I like to imagine that I can still hear his opinions.

My greatest indebtedness is to Riasanovsky himself. I want also to thank, given the breadth of history this text embraces, my other teachers in Russian history and culture over the years: Peter Kenez, John Ackerman, Victoria Bonnell, Grigory Freidin, and Reginald Zelnik, as well as many teachers in other fields, and my Russian history and literature colleagues at Illinois, especially Diane Koenker, John Randolph, Harriet Murav, Valeria Sobol, and Lilya Kaganovsky, from whom I continue to learn. No less, I am indebted to the many scholars whose books I have relied upon, from classics in the field to the most recent scholarship. In the traditional style of this textbook, there are no footnotes documenting the many writings I draw upon—obscuring my debts in a way I would never tolerate in student writing! But these debts are legion. Everything here owes something to others.

Many Russian history instructors, at the request of Oxford University Press, read the eighth edition and offered very useful critical comments. I am grateful to Guangqiu Xu, Sergei I. Zhuk, Gail Lenhoff, Charles Evans, Willard Sunderland, Mark B. Tauger, and the anonymous scholars and teachers who reviewed this new edition of A History of Russia. At my request, Gary Marker, a distinguished historian and also a former student of Riasanovsky’s, made extensive suggestions for revision, especially to the treatment of Russian history

through the eighteenth century. I am in awe of his knowledge and wisdom, though I am fully responsible for not following all of his good advice. Not least, it has been a pleasure to work with Charles Cavaliere at Oxford University Press, whose patience and editorial perspective have been exemplary. Essential work was contributed by Lindsay Profenno, who oversaw the book’s production; Debbie Ruel, who edited the manuscript with a sharp eye; and other production and editorial staff.

Speaking for both authors, I want to thank our families—wonderful spouses and amazing children, whose love and support and interesting lives have over many years sustained us. Finally, the ninth edition of A History of Russia, like all of its predecessors, is dedicated to our students, who have always been foremost in mind, and from whom we always learn.

Mark D. Steinberg

Introduction: The Lands and Peoples of the Eurasian Plain

Russia! what a marvelous phenomenon on the world scene! Russia— a distance of ten thousand versts [slightly more than a kilometer] in length on a straight line from the virtually central European river, across all of Asia and the Eastern Ocean, down to the remote American lands! A distance of five thousand versts in width from Persia, one of the southern Asiatic states, to the end of the inhabited world— to the North Pole. What state can equal it? Its half? How many states can match its twentieth, its fiftieth part? . . . Russia—a state which contains all types of soil, from the warmest to the coldest, from the burning environs of Erivan to icy Lapland; which abounds in all the products required for the needs, comforts, and pleasures of life, in accordance with its present state of development—a whole world, self-sufficient, independent, absolute.

MIKHAIL POGODIN,

1838

Broad and spacious is my homeland, Rich in rivers, fields, and woods, I know no other land like this, Where a man can breathe so free.

SONG OF THE MOTHERLAND, 1936

This book’s title might not seem like much to argue about, but its simplicity is deceptive. To say “A History” rather than “The History” of Russia already hints at uncertainty and argument—reminding us that when we tell the story of the past as “history” we are always interpreting, even when facts and fairness are a historian’s first principles, as the late Professor Nicholas Riasanovsky made the hallmark of this work since his first edition in 1963. And what about “of Russia”? What does it mean to trace the origins of a nation and an empire back into the lives of people before the concepts of nation and

empire existed and even before the arrival from the north of people known as the Rus (pronounced Roos), a likely origin for the later name Russia? What does it mean for us to group many different ethnicities, cultures, and identities— modern categories—under the heading “Russia”? Is this a type of historical imperialism, of conquest backward through time, as Ukrainians and others have argued? For Russia did not simply become a multiethnic empire as it expanded geographically; its history began as a multiethnic story—and an unstable one at that. And the history of unification and expansion was marked by benefits and progress but also violence, inequality, and discrimination. If a country’s history is a story of the connections of a given present to a past that people identify as their own—as Nicholas Riasanovsky often insisted in successive editions of this book—the specifics of how we construct those continuities are arguments. The devil is always in the detail. And while we must seek connections through time, we must also see the many divergent possibilities and directions in the past.

Before we speak of the peoples of the lands to be called Russia, we must think of the land itself—of the geographic and natural environments people experienced and worked, that shaped them and that they shaped. Of enormous importance was a vast northern Eurasian land mass with few barriers to migration, invasion, and expansion—leitmotifs in the history of this region. The great bulk of what became the Russian empire is a broad plain extending from central Europe deep into Siberia. Although numerous hills and chains of hills are scattered on its surface, they are not high enough or sufficiently massed to interfere appreciably with the flow of the mighty plain or the ease of moving across it. The Ural Mountains, ancient and weather-beaten, constitute no effective barrier between Europe and Asia, which they separate; besides, a broad gap of steppe land remains between the southern tips of the Ural chain and the Caspian and Aral seas. Impressive mountain ranges are restricted to what would become borderlands, including the Carpathians to the southwest, the high Caucasian chain in the south between the Black Sea and the Caspian, and the Pamir, Tien Shan, and Altai ranges farther east along the southern border. Human movement across this Eurasian plain has been aided by numerous rivers and lakes that connect regions, transport people, and provide resources.

This land contains a diversity of ecosystems that affected human experience and history in different ways—but mostly as disadvantage and challenge. As generations of migrants, settlers, and peasants learned firsthand, and as Russian scientists codified in nineteenth-century studies, this land was divided into natural “zones” extending east to west across the country. Historically, the early history of Slavic and Scandinavian settlement was concentrated in the mixed forest zone that extends from the Baltic and western frontier toward the Ural Mountains. In the medieval period, peasants began to move north into the coniferous taiga, a harsh land that stretches from southern Scandinavia to the Pacific Ocean. Together, these two huge forested belts accounted for over half of the territory of what would become the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. On the positive side, the fabulously rich forest

provided a wealth of usable timber, game, berries, edible plants, and fish, not to mention natural resources from coal to gold. On the other hand, its poor soils, short growing seasons, and icy winters made agriculture difficult. This was also a zone plagued by cold, flooding, famine, and fire. Still further north lies the tundra, a brutal land of swamps, moss, peat, and shrubs, reaching from the Kola Peninsula to the far northeastern edge of the Eurasian continent, and covering almost 15 percent of the territory that would become the Russian Empire. Few settlers ventured there before the end of the seventeenth century. To the south is the steppe, or prairie, reaching from southeastern Europe into Asia to the Altai Mountains. The western steppe (now Ukraine and southern Russia) was especially rich in “black soil,” and became the agricultural heartland of the country, though the short growing season (more like Canada than the United States) limited productivity. Finally, the southernmost zone, that of semi-desert and desert, extends from the Caspian Sea through Central Asia. It occupies nearly one-fifth of the total area of what would become the imperial and Soviet land mass.

Peoples and Cultures

“History” begins, we might say, when people begin to tell a story about a past built around connections (and boundaries), linkages down through time, and meaningful patterns. Of course, before that history began there were peoples, lives, and changes. Archaeologists have documented hunter-gatherer communities on the Eurasian plain already in the upper Paleolithic Age (between 35,000 and 10,000 years ago). They have found evidence of tools, weapons, mammoth-bone dwellings, jewelry, and art (some of it possibly connected to ancient religions). The Neolithic Age, beginning around 4,000 years before the Christian or Common Era (B.C.), was a period of rich cultural development, especially in the valleys of the Dnieper, Bug, and Dniester rivers in the south. Its remnants testify to the fact that agriculture was established in the area and also to a struggle between the sedentary tillers of the soil and invading nomads, a recurrent motif in the early history of these lands. This Neolithic people also used domestic animals, engaged in weaving, and had a ritual and religious life. Artifacts of copper, gold, and silver, found in numerous burial mounds, testify to the skill of artisans and to likely connections to other ancient civilizations.

Starting around 1000 B.C., life on these lands was altered dramatically by waves of migrating peoples from the Middle East and Asia. The Cimmerians, about whom information is meager—mostly from the writings of the Greek historian Herodotus, who spent some time in the Greek colony of Olbia at the mouth of the Bug River in the fifth century B.C., and from later archeological research—are usually considered to be the earliest such people. The Scythians, who came from Central Asia and spoke an Iranian language, entered the picture around 700 B.C., defeating the Cimmerians and taking control of this southern region and considerably expanding this domain. Scythian rule extended, at its greatest extent, from the Danube River into the Caucasus and