Exploring the Variety of Random Documents with Different Content

arose deplorable abuses. The Italian Inquisition, under the immediate direction of the popes, made its appearance in the fifth century: Pope St. Leo, after having ordered a juridical inquiry to be held concerning the Manicheans who had taken refuge in Rome, stated, “What has been done is not enough; the Inquisition must continue not only as an inducement for the devout to hold fast by their faith, but in order that those who have been led astray may be converted from their errors.” The primitive and real object of the Inquisition was to discover errors in doctrine, to stop them from being propagated, and to endeavour to enlighten and to win back those who had been perverted by the apostles of error.

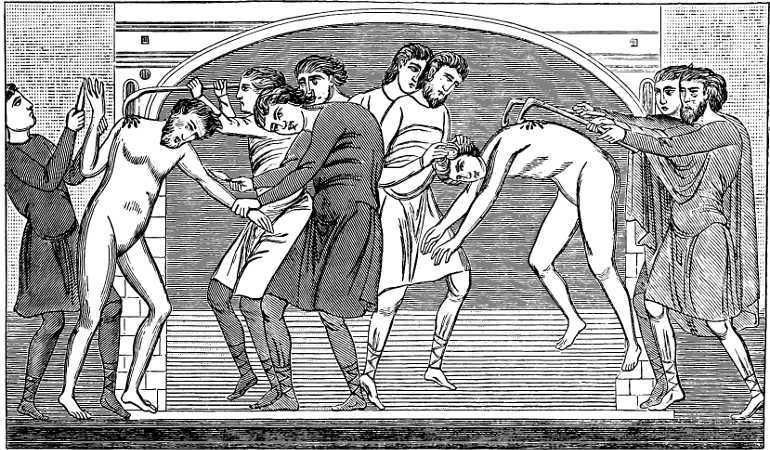

Fig. 330. Martyrdom of SS. Savin and Cyprian, their flesh being torn out with iron hooks. Fresco in the Church of St. Savin, Vienne (Eleventh Century). After the Drawings of M. Gérard-Séguin.

In the twelfth century Pope Lucius III., with a view of checking the progress of the Manicheans, who reappeared under the names of Catharists, Patarenes, the Poor of Lyons, &c., ordered “through the council of bishops, at the demand of the emperor (of Germany) and the lords of his court, that every bishop should visit the districts

of his diocese which were suspected of containing heretics once or twice a year.” They were to be denounced by every one, so that the bishop might summon them before him, make them renounce their heresies, or inflict upon them the punishment awarded by canonical law. Thus we see that religious error was regarded as a breach of public order, and that the princes looked upon the heretics as rebels or conspirators. This was in keeping with the ideas of the Middle Ages, when the whole social system reposed upon the Catholic faith. We must in fairness admit that, if the Inquisition of Rome was the earliest, and the only one which outlasted the Middle Ages, it was also the most moderate, for it alone never ordered capital punishment.

The Inquisition was introduced into France through a heresy of Eastern origin, which endeavoured to associate the pagan ideas of Armenian Manicheism with the ceremonies of Christianity. Originally centred at Toulouse and Albi (whence the name Albigenses), the new heretics, numbering about one thousand and fifty, gradually made their way into Perigord and the neighbouring provinces. Towards 1160 another sect, the Waldenses, founded by Peter de Valdo or de Vaux, arose at Lyons, and gave great trouble to the papacy. The Albigenses were inferior in morality even to the Waldenses, and professed still more dangerous opinions. Immediate followers of Manes the Persian, they had adopted his doctrine of the double nature of man, of fatalism, of the origin of good and evil, &c. —a monstrous doctrine, the direct consequence of which was a life of unbridled license. In spite of the pious efforts of King Robert (1022) and the sentence of condemnation pronounced at the Council of Toulouse (1118), the Manichean heresy of the Albigenses continued to spread throughout the southern provinces of France, and obtained fresh adherents every day even amongst the clergy and the nobility. Innocent III., elected sovereign pontiff in 1198, took alarm at the danger to the Christian religion, and determined to reduce these daring sectaries to obedience, openly protected as they then were by the Counts of Toulouse, Foix, and Béarn, and by the

Viscount of Béziers. But, before resorting to physical force, he at first tried persuasion.

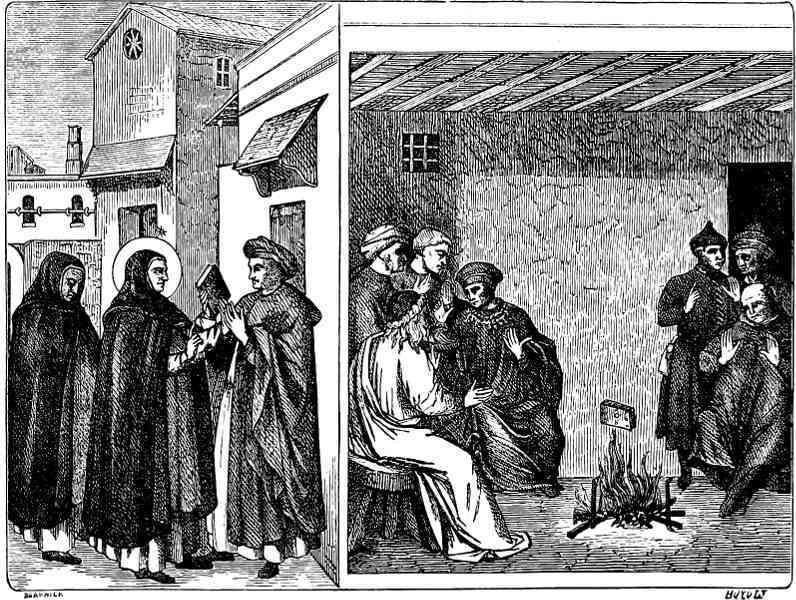

Fig. 331. St. Dominic handing to an envoy of the Albigenses a book containing the profession of faith in the Christian truths; to the right, this book having been cast into the fire, is leaping out of the flames, whilst the heretic’s book is being consumed. Predella of the “Couronnement de la Vierge” by Fra Angelico, in the Louvre (Fifteenth Century).

Two monks, Guy and Raynier, of the Cistercian order, accordingly repaired to the south of France to seek out these heretics. They were the first commissioners of the Holy See to whom might properly belong the title of inquisitors. The failure of their mission decided Innocent III. to give full powers to Peter de Castelnau, Archdeacon of Magliano, and to another Cistercian monk named Ralph. These two monks, accompanied by Amalric, Abbot of Citeaux, preached against the heresy of the Albigenses at Toulouse,

Narbonne, Viviers, Carcassonne, and Montpellier, but the heretics only displayed greater perseverance. Peter de Castelnau and Brother Ralph, disheartened at this result, enlisted in their difficult mission twelve brothers of their own order and two distinguished Spanish prelates—Diego de Azeles, Bishop of Osma, and the sub-prior of his cathedral, Dominic Guzman, who, having witnessed the progress of heresy in Languedoc, went to Italy to obtain the Holy Father’s permission to preach against it. Dominic had given proof of a gentleness, zeal, and piety worthy of the apostles, and the renown of his exemplary life was counted upon to give authority to his preaching (Fig. 331). Yet he was no less unsuccessful than the preceding commissioners sent by the pope. Insulted and mocked by an ignorant and brutal populace, he could not help exclaiming, “O Lord, let thy hand smite them, that thy punishment at least may open their eyes!” The legate Peter de Castelnau, in despair at the failure of his efforts to restore quietude and faith to men’s minds, determined to address himself directly to the Count of Toulouse, Raymond VI., and to formally demand of him to lend his aid to the papal legates, or else to proclaim openly that he sided with the heretics. After an interview during which bitter language was exchanged, two of the esquires of the Count of Toulouse believed that they would be complying with their master’s secret wishes by assassinating the courageous legate upon the banks of the Rhône (1208). Innocent III., when the news of this murder reached him, at once determined to set on foot a new crusade against the Albigenses. He appointed Milon in the room of Peter de Castelnau, and declared that he took under his immediate protection all the faithful who should take up arms for the defence of the Church. The Count of Toulouse did public penance, and his nephew Raymond Viscount of Béziers was handed over to the papal legates. The town of Béziers, taken by assault (July 22nd, 1209), was a scene of terrible carnage, for the crusaders gave no quarter—twenty thousand inhabitants were massacred without distinction of age or sex, and seven thousand were burnt in a church in which they had taken refuge.

Simon de Montfort, who was at the head of the expedition, accepted the effects of the Viscount of Béziers, and continued the war against the heretics. In 1213, before the walls of Muret, he defeated Peter II., King of Arragon, an ally of the Albigenses, who was besieging the town, and he afterwards stripped the Count of Toulouse of his domains, against the wish of Innocent III., who would have preferred that the count’s hereditary rights, and still more those of his son, should have been respected.

Simon was supported by Louis, son of Philip Augustus, who lost no time in fulfilling the vow which he had made to take up arms against the Manicheans of Languedoc, and, as the battle of Bouvines (1214) had led to a five years’ truce between the Kings of France and England, he joined the Catholic forces in the following year. In 1218 Toulouse rose in revolt, and Simon de Montfort was mortally wounded by a stone during the siege. His son Amaury put himself forward as heir to his father’s domains, and endeavoured to establish his claims to the countships of Béziers and Toulouse, but he eventually abandoned them in favour of the French monarch. Very rigorous measures were taken to put down the heretics. An order issued by the bishop of Toulouse decreed that “the inhabitants of the districts infected with heresy shall pay one mark in silver for every Waldensian found within their boundaries; the house in which he is captured, those in which he has preached, shall be razed to the ground, and the property belonging to the owner of these houses confiscated. The goods of the pervert shall also be confiscated, as well as those appertaining to any person neglecting to wear or to display the two coloured crosses which should be sewn on to the breast of the penitent’s garment.” The Holy See, on its part, was not remaining inactive during this time, as in 1215 the fourth Lateran Council had excommunicated the Manicheans, the Waldenses, and the Albigenses. The third canon of that council declared that “the heretics who are condemned shall be handed over to the secular arm, in order that they may receive their merited punishment; the clerks shall be previously unfrocked.”

Just before this council terminated its sittings, Dominic, presented to Pope Innocent III., obtained, as a recompense for the services which he had rendered to the Church militant, leave to found the order of Preaching-Brothers, who from him took the name, by which they are more generally known, of Dominicans.

Their pious founder battled against heresy with purely spiritual weapons, and it is perhaps scarcely necessary to mention that he it was who, with a view to obtaining the conversion of heretics, introduced the custom of reciting the rosary. On his return to Toulouse, which eventually became the centre of the Inquisition, he delegated to eight provincials of his order, in France, Provence, Lombardy, Romagna, Germany, Hungary, England, and Spain the special mission of preaching against heresy. And, lastly, in 1229 Raymond VII., who had succeeded to his paternal inheritance after doing public penance, was reconciled to the Church and reinstated in his countship of Toulouse. His only daughter married one of the king’s brothers, thus insuring the transmission of his lands to the French crown.

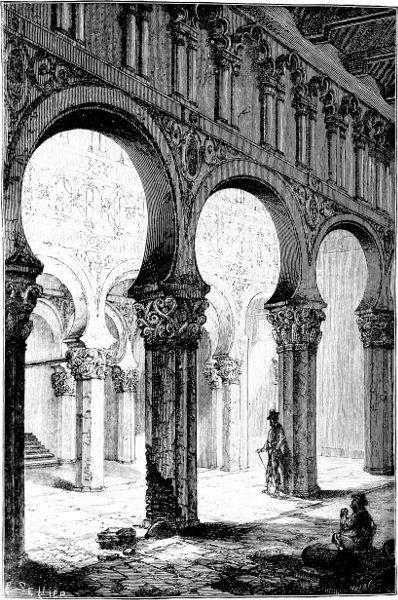

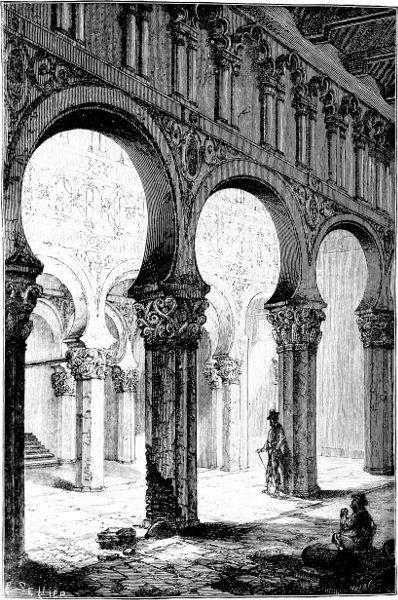

Fig. 332. Great Synagogue of Toledo (Third Century), restored at different periods, and consecrated for Catholic worship, under the name of Santa Maria Blanca, after the expulsion of the Jews in 1405: now used as a military storehouse.—After a Drawing by Don Manuel de Assas.

Louis IX. lost no time in taking measures to consolidate the results of this pacific arrangement. He addressed to all his subjects, in the dioceses of Narbonne, Cahors, Rodez, Agen, Arles, and Nîmes,

a decree composed of ten clauses, by which it was sought to effect the repression of heresy with the help of the secular clergy. Any one who had been excommunicated for more than a year was to be compelled, by seizure of his goods, to return to the Church. The tithes, which had long been kept back, were re-established. The barons, the vassals, the large towns and royal bailiwicks were sworn to observe and execute this decree. Even the king’s brother, when he assumed possession of the country, took the same oath for himself and his subjects. The Inquisition soon appeared to be unnecessary in France, and, with the consent of the Holy See, it suspended its action in the countship of Toulouse in 1237.

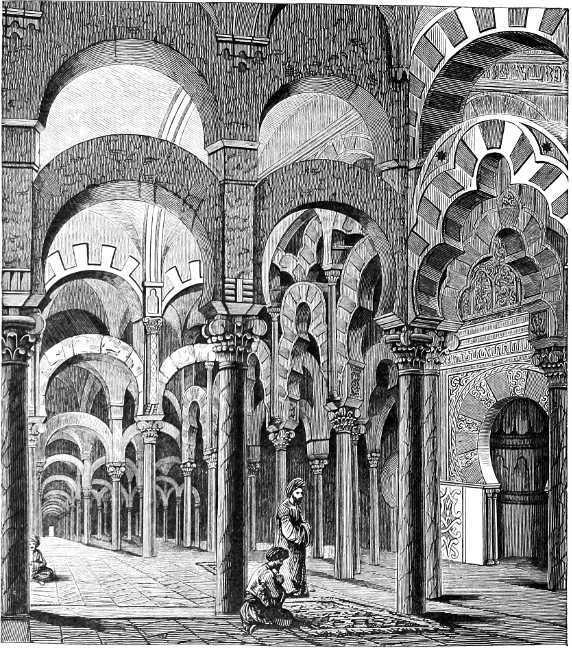

In Spain, the Inquisition was royal rather than papal. If we would understand the part played by this remarkable tribunal, it must be remembered that Spain took seven centuries to conquer its independence against the Moors and the Jews. These latter, while feigning a readiness to be converted, none the less maintained their antipathy for the Christian religion and their hatred of the Christians. Thus, when Ferdinand and Isabella had the whole of Spain under their authority, they considered it necessary to establish religious unity, in order to preserve national unity, and the Moors and Jews were ordered to quit the country or abjure their creeds (Figs. 332 and 333). The two sovereigns, who looked at the question in a political light, had established in their dominions a special Inquisition placed under their immediate control. The popes protested at once against the pretension of the Catholic monarchs to themselves superintend the Inquisition, and, on the tribunal being formed, Pope Sixtus IV. recalled his legate from the Spanish Court, which latter in turn withdrew its ambassador from Rome. A reconciliation, however, was effected, and a bull legalising the Spanish Inquisition was granted; but Pope Sixtus IV. soon regretted what he had done when he came to know of its excesses. The Spanish sovereigns, upon the other hand, did all they could to prevent the appeals made by condemned heretics from being heard at the Court of Rome, while the popes were obliged to employ stratagem in order to protect the penitent heretics from the merciless severity of the Inquisition.

Llorente tells us that on many occasions a great number of heretics received secret absolution by order of the pope, but he further adds that these papal amnesties were not always approved of by the Spanish government. Leo X. actually excommunicated the Inquisitors of Toledo, and Charles V., when he became emperor, pretended to lean in favour of the Lutheran reform in order to prevent Leo from interfering any further with the Spanish Inquisition. This Inquisition was assisted by three corporate bodies, namely, the Holy Hermandad, the Cruciata, and the Militia of Christ.

Fig. 333. Interior of the Ancient Mosque at Cordova, now a Catholic Cathedral; built in the Eighth Century by Abderhaman I., and altered for Catholic worship after the conversion of the Moors; it is one of the largest and most splendid monuments of Moorish architecture.

The Holy Hermandad (a corruption of the Latin word germanitas, confraternity) was at first an association of police officers employed in the protection of the streets and highways. Originally established in the three royal residences of Toledo, Cuidad-Real, and Talavera, it

eventually became a military force, whose chief mission was to put into execution the orders of the Inquisition.

The Cruciata, a society composed of archbishops, bishops, and other personages of mark, was entrusted, under various circumstances, with the task of seeing that the laws of the Church were obeyed and carried out amongst Catholics.

The Family of the Inquisition, or the Militia of Christ, created during the pontificate of Honorius III., and analogous to the Order of the Templars, placed its forces at the service of the Inquisitors, and its pious zeal earned for it the good opinion of Pope Gregory IX.

As we have already mentioned, it was in 1481, during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, that the Inquisition, provided with a new code of regulations, acquired a formidable power. Chiefly intended to bring to trial the Jews and the Moors who had again relapsed into paganism, it was then that it got the name of TheHolyOffice, and was superintended by a grand inquisitor-general and a council, termed The Supreme, consisting of forty-five members. When the Holy Office had a heretic, or any one suspected of being one, arrested, its agents stripped the accused person of all he had about his person, and took a detailed inventory of his clothing and furniture, in order that they might be restored to him intact should he prove to be innocent. The money so seized, whether in gold or silver, belonged by right to the tribunal, and went to pay the costs of the procedure. These formalities over, the accused person was taken to prison.

Of prisons, the Inquisition had several kinds: 1st, the common prison, in which were confined persons accused merely of ordinary misdemeanour, and who, consequently, were allowed to communicate with their families and friends; 2nd, the prison of mercyor ofpenitence, which was set apart for those who were to be detained only temporarily; 3rd, the intermediateprison, reserved for those who had committed some ordinary delinquency which brought them within the jurisdiction of the Holy Office; 4th, the secretprison, the inmates of which were kept in solitary confinement. The

dungeons of the Inquisition were like all those constructed in the Middle Ages.

After an incarceration which varied in length, the prisoner was conducted, when the day of trial arrived, to the large audience hall, which was hung with black, and adorned with a figure of Christ upon the cross, the body being of ivory and the cross of ebony. At the extreme end, before a circular table, sat the Inquisitor-general in a raised chair covered with black velvet and surmounted by a canopy of the same material. To his right and left, seats placed at a lower elevation were reserved for the Inquisitors, who, with the secretary, composed the tribunal. Two clerks of the court took down the questions put by the president and the answers made by the accused; behind them stood the spies of the Inquisition, and four men wearing long black robes, with their faces concealed by a mask with openings for the mouth, the nose, and the eyes.

The prisoner was seated upon a kind of raised stool placed opposite the Inquisitor; when, after a long interrogatory, he failed to avow his guilt, he was taken to the torture-chamber, preceded by the Inquisitor and the four mysterious men in black who had been present at the trial. Here he was again exhorted to abjure his errors, and, if these fresh entreaties were powerless to move him, he was handed over to the torturer, who put him to the torture with one of the four agencies employed by justice—the cord, the scourge, fire, or water (see the chapter on “Punishments,” in MANNERS AND CUSTOMS OF THE MIDDLE AGES).

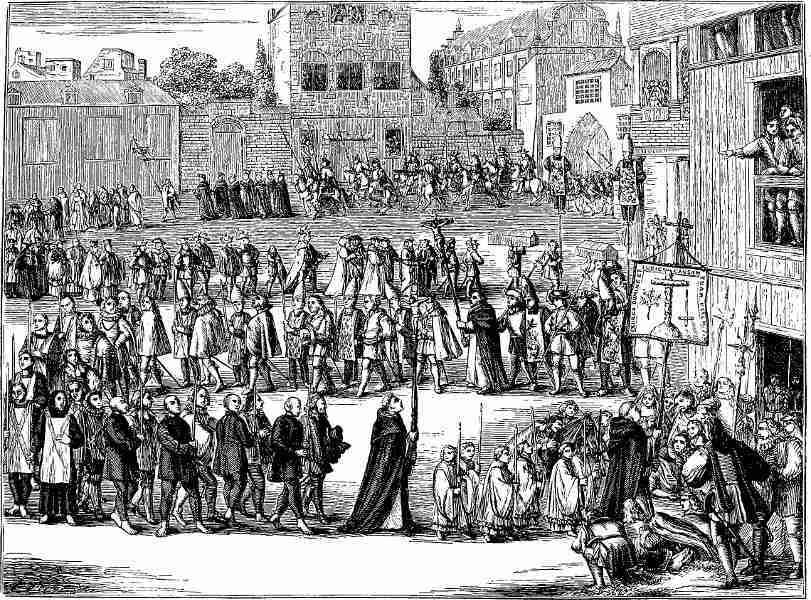

The torture as used by the tribunals of the Inquisition did not differ from that employed by the civil tribunals, which, using it as unsparingly, scarcely attained a more satisfactory result, for the victim steeled himself against the pain and generally refused to reply to this interrogatory, though accompanied by inconceivable tortures. The solemn delivery of the judgment of the Inquisition and the execution of its sentences were preceded by a peculiar ceremony, designated in Spain and its dependencies by the name of Auto-dafé, or Act of Faith. In most Auto-da-fés, the dismal procession was

headed by a double file of Dominican brothers, before whom was carried the banner of the Holy Office (Fig. 334), with the device, “Justitia et misericordia.” Behind them came the condemned, followed by the spies of the Inquisition and the executioner.

Fig. 334. An Auto-da-fé Procession, in Spain, according to the ceremonial observed from the Fourteenth Century. Fac-simile of a large Engraving on copper in the work of Philip of Limborch, entitled “Historia Inquisitionis:” folio, Amsterdam, 1692.

There were many kinds of san-benito for different classes of penitents. The first, for heretics who were reconciled to the Church before sentence had been passed, consisted of a yellow scapulary, with large reddish-coloured St. Andrew’s cross, and of a round pyramid-shaped cap called coroza, of the same material as the sanbenito and with similar crosses; but no flames were represented on the garments, as the accused by timely repentance had escaped the punishment of burning (Fig. 335).

The second, for those who, sentenced to be burnt, had subsequently recanted, was made up of a san-benito and a coroza of the same material. The scapulary was covered with tongues of fire pointing downwards, to indicate that the wearer (Fig. 336) would not be burnt alive, inasmuch as he was to be strangled before being placed upon the burning pile.

Fig. 335. San-benito. Garment worn by those who escaped burning by making a confession before being sentenced.

336.

worn by those who escaped being burnt alive by making a confession after they had been condemned.

Fig.

Fuego revolto. Garment

Fig. 337. Samarra. Garment worn by those who, refusing to confess, were about to be burnt.

Fac-simile of Engravings on Copper in the work of Philip of Limborch, entitled “Historia Inquisitionis:” in folio, Amsterdam, 1592.

The third, worn by those who died impenitent, had at the lower end the head of a man in the midst of fire and enveloped in flames. The other parts of the garment were covered with forked flames shooting upwards, as a token that the heretic would actually be burnt alive. Grotesque figures of demons were also represented upon the san-benito and upon the coroza as well.

At the church whither the cortége repaired, chanting prayers on its way, ten white tapers were alight in silver candlesticks upon the high altar, which was hung in black; to the right, there was a kind of raised dais for the Inquisitor and his councillors; to the left, another such a one for the king and his court. Facing the high altar was a scaffolding covered with black cloth upon which the reconciledstood to make their abjurations upon missals which had been opened and arranged beforehand.

After the reconciliation of these latter, the impenitent heretics were handed over to the secular power, together with the prisoners who had been guilty of ordinary misdemeanour. The Auto-da-fé was then over, and the Inquisitors withdrew. An historian, in giving a detailed account of a trial before the tribunals of the Inquisition, tells us that the civil punishment was not inflicted until the day after the Auto-da-fé. Nor was it always the case that it was followed by execution, for Llorente cites that of February 12th, 1486, at Toledo, when there were seven hundred and fifty heretics brought up for punishment, not one of whom was put to death, though they had to do public penance. At another great Auto-da-fé, also held at Toledo in April of the same year, out of nine hundred repentant or condemned persons none underwent the extreme penalty. A third, on the 1st of May, comprised seven hundred and fifty persons; and at a fourth, on the 10th of December, there were nine hundred and fifty, but in both these instances no blood was shed. Out of a total of three thousand three hundred persons who had to do penance for transgressing the rules of the Church at this epoch, Llorente states that only twenty-seven were put to death. It must be remembered that the Spanish Inquisition, in conformity with the royal decree, had to try not only heretics, but those accused of unnatural crimes,

brigands, lay or clerical seducers, blasphemers, persons guilty of sacrilege, usurers, and even murderers and rebels. In addition to this, those who supplied the enemy with horses and stores in time of war, together with the then frequent cases of sorcery, magic, and other similar frauds, were also brought within the jurisdiction of the tribunals of the Inquisition. Thus the twenty-seven individuals who were executed in 1486 may have been made up of malefactors of every class.

The political aim of the kings of Spain was attained, for the maintenance of religious unity preserved the kingdom from the bloody catastrophes which at that period spread desolation throughout France and England. This is admitted even by Voltaire, in his “Essai sur l’Histoire Générale.” While deploring the horrors of the Inquisition, he says, “In Spain there were none of those bloody revolutions, conspiracies, or cruel reprisals which disgraced every other European nation. Neither Count Olivarès nor the Duke of Lerma sent their enemies to the scaffold, and sovereigns were never assassinated as in France, nor did they suffer beneath the headsman’s axe, as in England.”

Fig. 338. Philip II., King of Spain. From the work of Cesare Vecellio: 8vo, 1590.

The Inquisition was less successful in the Netherlands, for the Protestant cause made great progress in Holland during the reign of Charles V. The nobility and the upper clergy, indignant at the rigorous measures adopted by Philip II. (Fig. 338) in his efforts to put down heresy, countenanced the general uprising against the Spaniards. Emboldened thereby, the Protestants flew to arms, the churches were burnt, the priests and monks were massacred, and

the Catholic form of worship suppressed in many localities. Philip dispatched thither the notorious Duke of Alva, who, on assuming the command, instituted the council of troubles, which the people nicknamed the councilofblood. The religious question resolved itself into a struggle for national independence. A bitter war resulted in the definite separation of the United Provinces, which afterwards became the kingdom of Holland. Belgium, created an independent province, was handed over with hereditary rights to Archduke Albert and his wife Isabella, daughter of Philip II.

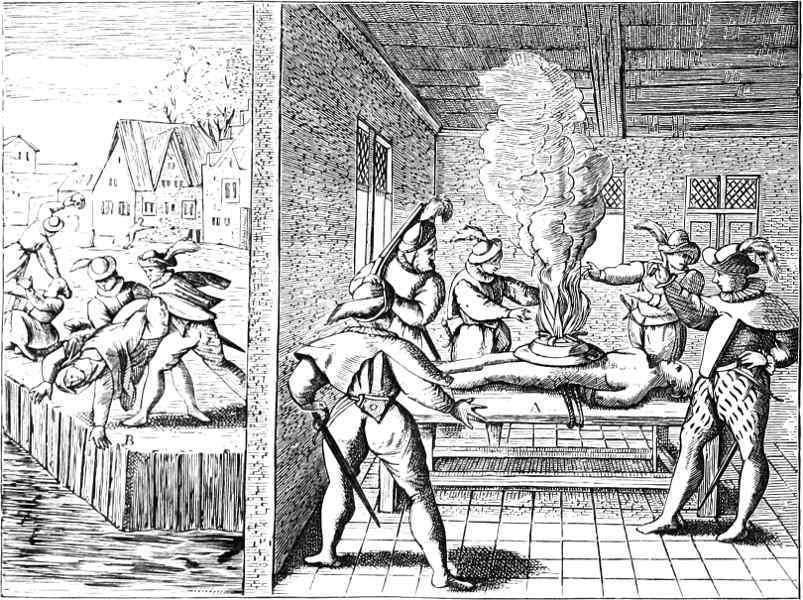

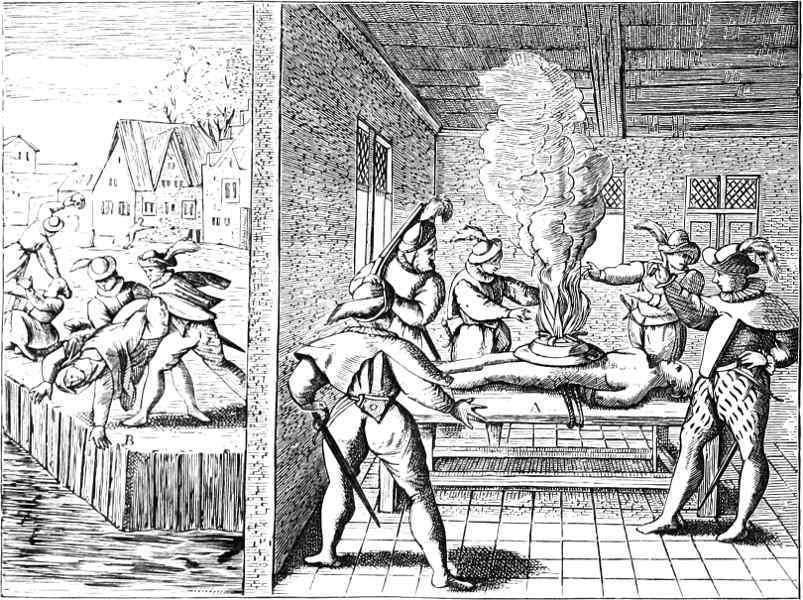

Fig. 339.—Cruelties committed by the Gueux, in Holland. A. Master John Jerome, of Edam, and other Catholics of Hoorn, being put to the torture, at Scagen, in Northern Holland. Those who survive the first tortures are tied down upon their backs, a large cauldron turned upside down is placed upon their naked stomachs, with a number of large dormice underneath. A fire is lighted upon the top of the cauldron which enrages the dormice; and as they are unable to creep under the edges of the cauldron, they burrow into the entrails of the victim. B. Ursula Talèse, a nun of Haarlem, having refused to renounce her faith when made to stand beneath the gibbet upon which her father had been hung, is thrown into the water and drowned. C. Her sister, bewailing her fate and that of her father, also refuses to change her creed, and her skull is beaten in with a large stone. Fac-simile of an Engraving on Copper in the “Theatrum Crudelitatum nostri Temporis” (4to, Antwerp, 1587); with a translation of the explanations given.

The United Provinces were no sooner constituted than, notwithstanding the Protestant principle of the liberty of free inquiry, they obeyed that instinct which impels all governments to religious

unity—Spain was outdone in the refinement of punishments which they invented to use against the Catholics who refused to change their faith (Fig. 339). Nor was it against the Catholics only that the Protestant Inquisition exercised its rigorous authority. In countries where Calvinists and Lutherans were brought into juxtaposition, religious persecution broke out between the various reformed Churches, always, too, under the instinctive influence that religious unity was necessary to ensure the stability of the State. A distinguished writer, Menzel, in his “New History of the Germans since the Reformation,” gives some very interesting details concerning this internecine struggle. At the end of the sixteenth century, when, at the death of the Elector of Saxony, Christian I., on September 25th, 1591, the government of Saxony fell into the hands of Duke William of Altenburg, who was a rigid Lutheran, the Calvinist party in Germany thought that the golden age was about to return. Chancellor Crell, who in Christian’s lifetime had treated the Lutherans with slight show of mercy, was cast into prison, together with Gunderman, a Leipsic preacher. After five months’ incarceration, the latter signed the “Formula of Concord,” in order that he might be able to visit his wife, whom he had left enceinte, but he had no sooner appended his signature than he was told that she had hung herself in a fit of despair. The unfortunate man went out of his mind. Other preachers were treated with almost equal severity; and at Leipsic, in 1593, the Lutheran party set fire to the houses of the Calvinists, who had to fly from the city to escape assassination. Such was also the case in Silesia. Upon the 22nd of September, 1601, Chancellor Crell was condemned to death, after having been kept ten years in prison, and he was beheaded on the 10th of October.

At Brunswick, in 1603, the Lutheran preachers excommunicated the captain of the burghers, one Brabant; in 1604 it was rumoured that he had made a pact with the devil, and that the latter had been seen following them in the form of a crow. Brabant tried to escape, but broke his leg in the attempt. Brought back to Brunswick amidst the hootings of the populace, who regarded him as a traitor and a magician, he was three times put to the most cruel torture, to

terminate which he avowed himself guilty of all the crimes laid to his charge. His companions in misfortune were treated with equal cruelty. While Zachary Druseman was suspended by the arms in the torture-chamber, his judges went off to their supper. The victim implored the executioner, by the wounds of our Lord Jesus Christ, to let him down for a single moment and loosen the screws which were crushing his feet, but the latter replied that he must wait until the judges returned. When they came in an hour afterwards, completely intoxicated, Druseman was dead. Menzel goes on to tell us that on St. Michael’s Day the Lutheran preachers, at the request of the town council, undertook to justify from the pulpit the executions which had been incessantly going on, and that on the 9th of December a thanksgiving service was held in all the churches, in front of which the gibbets and scaffolds were still displayed.

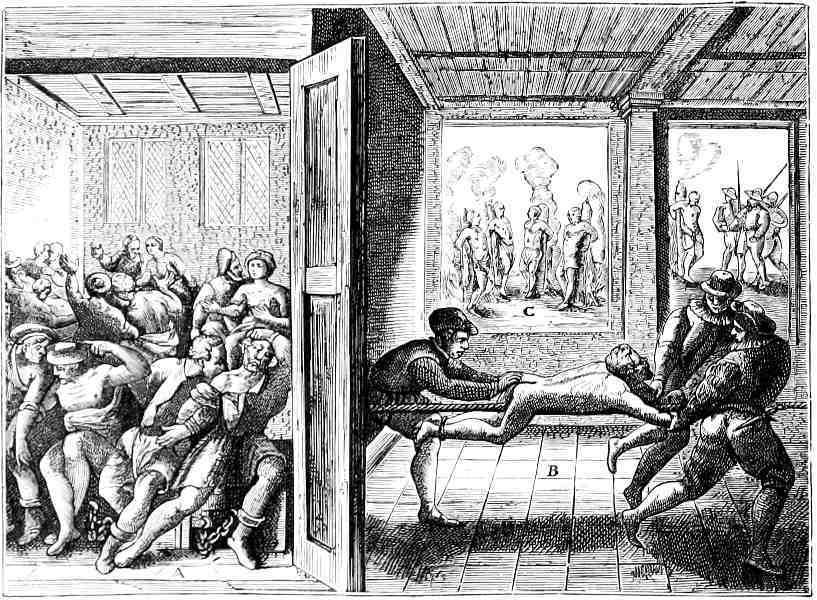

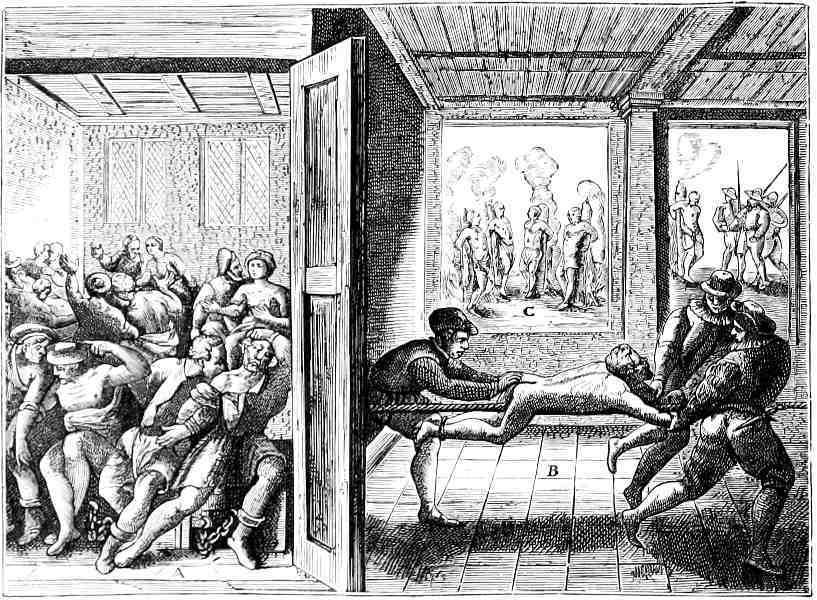

Fig. 340. Tortures inflicted upon Catholics by the Huguenots in the South of France. Thirty Catholics, imprisoned at Augoulême, in the house of a burgher of the name of Papin, are tortured in various ways: A. Some, deprived of food, are chained together in pairs, so that, becoming delirious through hunger, they may tear each other to pieces. B. Some are dragged naked along a tightly-drawn rope, which acts like a saw, cutting the body in two. C. Several are attached to stakes, and fires lighted a short distance behind them, so that their bodies may burn slowly.—Fac-simile of an Engraving on copper in the “Theatrum Crudelitatum nostri Temporis” (4to, Antwerp, 1587); with a translation of the explanations given.

In the southern provinces of France, where the party of the Reformation acquired the upper hand, excesses were committed which were as much reprobated by the more enlightened of the Protestants as by the Catholics. The town of Angoulême in particular was the scene of many such cruelties (Fig. 340).

The dominant party was everywhere guilty of extreme intolerance, but nowhere was the persecution carried on upon so

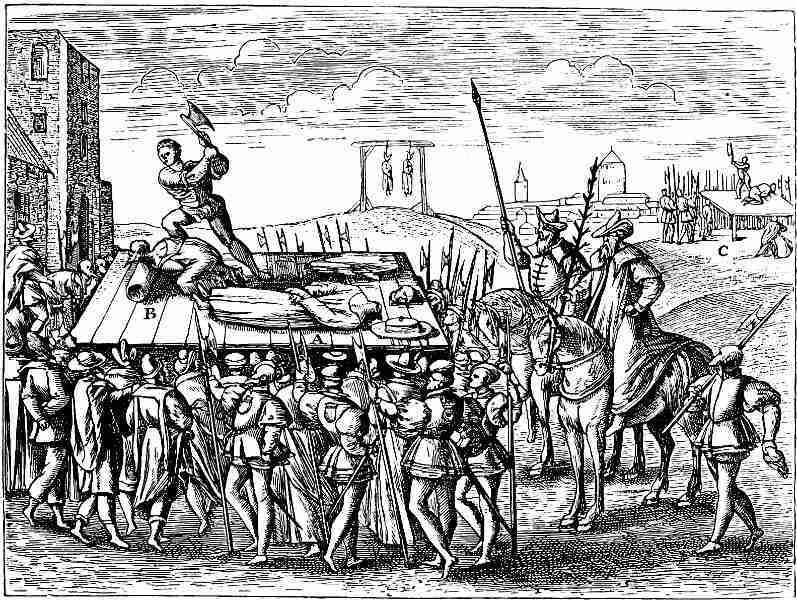

large a scale as in unhappy England. Protestant writers cannot find expressions strong enough to characterize the unheard-of violence to which Henry VIII. had recourse with a view to establish religious unity in his kingdom.

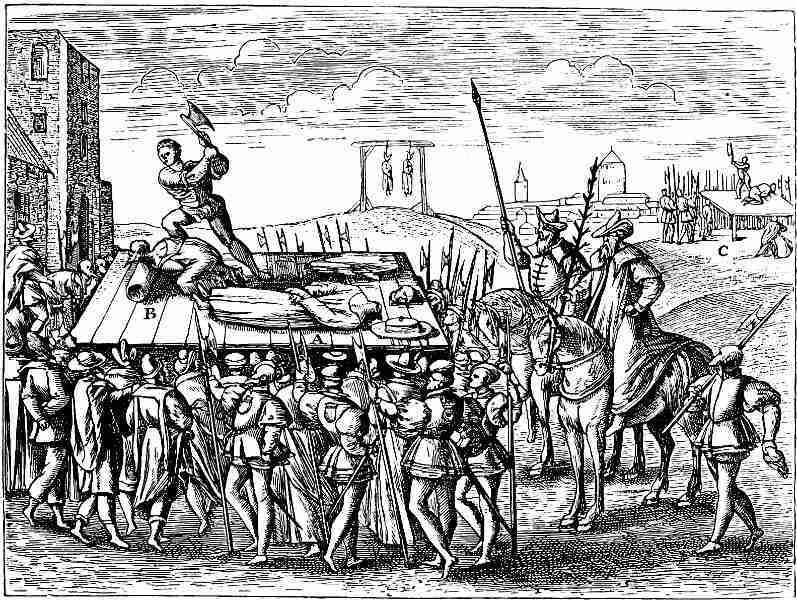

Fig. 341. Punishments decreed by Henry VIII. against the Catholics. A. John Fisher, Cardinal-Bishop of Rochester, eighty years of age, condemned to death on the 17th of June, 1535, is beheaded on the 22nd of the same month. B. Chancellor Thomas More is also beheaded on the 9th of July, 1535. C. The Countess of Salisbury, made to answer for the accusations brought against her son, who had left the country, after being condemned to death, is beheaded. Fac-simile of a Copper-plate in the “Theatrum Crudelitatum nostri Temporis” (Antwerp, 1587); with a translation of the explanations given. Cobbett, in his “History of the English Reformation,” says, “Previous to this reign of bloodshed not more than three persons on the average were tried in each county at the annual assizes, but now there were as many as sixty thousand persons in prison at a time. In