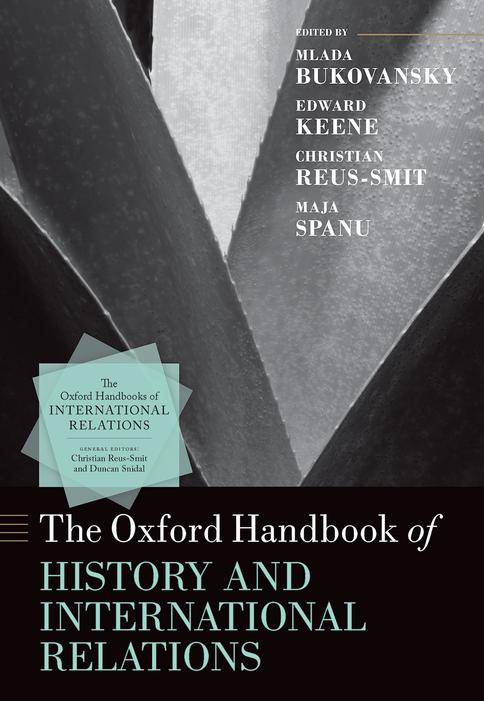

List of Contributors

Lucian M. Ashworth is Professor of Political Science in the Department of Political Science at the Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Tarak Barkawi is Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Martin J. Bayly is Assistant Professor in International Relations Teory in the International Relations Department at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Duncan Bell is Professor of Political Tought and International Relations at the University of Cambridge.

Lauren Benton is Barton M. Biggs Professor of History and Professor of Law at Yale University.

Jordan Branch is Associate Professor of Government at Claremont McKenna College.

Quentin Bruneau is Assistant Professor of Politics at the New School for Social Research.

Mlada Bukovansky is Professor of Government at Smith College, Northampton Massachusetts.

Zeynep Gulsah Capan is Senior Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Erfurt.

Chen Yudan is Associate Professor in International Politics in the School of International Relations and Public Afairs at Fudan University.

Julia Costa Lopez is Assistant Professor in History and Teory of International Relations at the University of Groningen.

Alexander E. Davis is Lecturer in Political Science (International Relations) at the University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences.

Megan Donaldson is Associate Professor of Public International Law at University College London.

Linda Frey is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Montana.

Marsha Frey is Emeritus Professor of History at Kansas State University. Michel Gobat is Professor of History at the University of Pittsburgh.

Daniel Gordon is Professor of History at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Daniel Gorman is Professor of History at the University of Waterloo and a faculty member at the Balsillie School of International Afairs.

Daniel M. Green is Associate Professor of International Relations in the Department of Political Science at the University of Delaware.

Jonathan Harris is Professor of the History of Byzantium at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Eric Helleiner is Professor and University Research Chair in the Department of Political Science at the University of Waterloo.

Talbot Imlay is Professor of History at the Université Laval in Quebec.

Peter Jackson holds the Chair in Global Security (History) in the School of Humanities at the University of Glasgow.

David C. Kang is Maria Crutcher Professor of International Relations at the University of Southern California.

Edward Keene is Associate Professor of International Relations at the University of Oxford and Ofcial Student of Politics at Christ Church.

Duncan Kelly is Professor of Political Tought and Intellectual History in the Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Jesus College.

George Lawson is Professor of International Relations in the Coral Bell School at the Australian National University.

Richard Ned Lebow is Professor of International Political Teory in the War Studies Department of King’s College London and Bye-Fellow of Pembroke College, University of Cambridge.

Christopher J. Lee is Professor of African History, World History, and African Literature at Te Africa Institute, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates.

Cecelia Lynch is Professor of Political Science at the University of California.

Nivi Manchanda is Senior Lecturer in international politics at Queen Mary University of London.

James Mayall is Emeritus Sir Patrick Sheehy Professor of International Relations at the University of Cambridge and a fellow of Sidney Sussex College.

Jennifer Mitzen is Professor in the Department of Political Science at Ohio State University.

A. Dirk Moses is the Anne and Bernard Spitzer Chair of International Relations at the City College of New York.

Jeppe Mulich is Lecturer in Modern History in the Department of International Politics at City, University of London.

Jacinta O’Hagan is Associate Professor in International Relations in the School of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Queensland.

Maïa Pal is Senior Lecturer in International Relations at Oxford Brookes University.

Andrea Paras is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Guelph.

John Anthony Pella, Jr is a Research Fellow in the School of International Afairs at Fudan University.

Benoît Pelopidas is Associate Professor of International Relations at Sciences Po (CERI).

Andrew Phillips is Associate Professor of International Relations and Strategy in the School of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Queensland.

Signe Predmore is a PhD Candidate in Political Science and Women, Gender & Sexuality Studies at University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Christian Reus-Smit is Professor of International Relations at the University of Queensland and a Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia.

Jef Rogg is Assistant Professor in the Department of Intelligence and Security Studies at Te Citadel.

Or Rosenboim is Director of the Centre for Modern History and Senior Lecturer at the Department of International Politics at City, University of London.

Karl Schweizer is Professor in the Federated Department of History at NJIT/Rutgers University.

Eric Selbin is Professor and Chair of Political Science & Holder of the Lucy King Brown Chair at Southwestern University.

Laura Sjoberg is British Academy Global Professor of Politics and International Relations and Director of the Gender Institute at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Maja Spanu is Afliated Lecturer at University of Cambridge and Head of Research and International Afairs, Fondation de France.

Jan Stockbruegger is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Political Science at Copenhagen University.

Chika Tonooka is a Research Fellow in History at Pembroke College, University of Cambridge.

Corinna R. Unger is Professor of Global and Colonial History (19th and 20th centuries) at the Department of History, European University Institute.

Claire Vergerio is Assistant Professor of International Relations at Leiden University’s Institute of Political Science.

R. B. J. Walker is Professor Emeritus of Political Science, University of Victoria and Professor Colaborador do IRI, PUC-Rio de Janeiro.

Michael C. Williams is University Research Professor of International Politics in the Graduate School of Public and International Afairs at the University of Ottawa.

Kevin L. Young is Associate Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Musab Younis is Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary University of London.

Ayşe Zarakol is Professor of International Relations at the University of Cambridge and a Politics Fellow at Emmanuel College.

Yongjin Zhang is Professor of International Politics in the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies at the University of Bristol.

Modernity and Granularity in History and International Relations

Mlada Bukovansky and Edward Keene

The idea for this Handbook on History and International Relations originated from two propositions. One is that we cannot make sense of how international relations work without understanding the history of how diferent forms of global political orders have developed; the other is that the history of the world as a whole cannot be written without taking account of the existence of an international system (or systems) on a global scale. To capture the various dimensions of this interdependence between the academic disciplines of International Relations (IR) and History, the Handbook is organized around ‘Readings’, ‘Practices’, ‘Locales’, and ‘Moments’. Te frst section, ‘Readings’, examines the contexts within which the encounter between historians and IR scholars takes place, with writers from both felds refecting on diferent ways in which their inquiries intersect. Tereafer we look outward to see how current research is re-shaping our understanding of how the world we live in today developed. Rather than work towards a single grand overarching narrative here—the story of historical IR—our goal is to show how diferent perspectives inform our sense of the international and global dimensions of historical becoming in a rich variety of ways.

To establish coherence and points of comparison across this diversity, we have asked all our authors to focus on two key themes that give them a number of ‘hooks’ on which they can pin their analyses. We will explain these in more detail next, but it may be helpful to give a brief summary of these fundamental elements of our project here at the very beginning of this introductory chapter, to explain how they inform the arrangement of the Handbook across its various sections, so that readers can approach the many chapters presented here with a clearer understanding of how the volume is organized, and why we have chosen to arrange it that way.

Te frst set of questions we posed for our authors is about the chronological development of diferent ways of ordering the international, and how to navigate between structural

change and continuity. To do this, we chose to adopt a focus on modernity as an organizing concept, or possibly critical foil. We recognize that there are potential dangers in putting this idea at the centre of our refections on history and IR, and that some would see a fxation with modernity as a signifcant source of problems within mainstream IR scholarship. For example, the chapter by Ayse Zarakol on ‘Modernity and Modernities in IR’ (Chapter 28) ofers the most direct engagement with this theme, and illustrates the refective and critical manner in which we hope to handle the concept throughout the Handbook. Zarakol mounts a forceful argument that the academic discipline of IR has been powerfully infuenced by a specifc version of modernization theory that generates a number of dubious propositions, provocatively labelled as three distinct ‘Wrong Answers’ to the questions of what modernity is, who made it, and how it interacted with other ways of organizing social, economic and political life as it spread around the world. Zarakol contends that all of these ‘Wrong Answers’ spring from an over-commitment to ‘the idea that “modernity” is a unique set of developments that was experienced frst or only by the West’ and radically underestimates the agency of non-Western actors.

One important consequence of this is a tendency for IR theory to coalesce around a particular conception of state sovereignty, and it is clear that this risks importing a specifc Western perspective into any treatment of historical IR and international history. We have therefore actively encouraged authors to imagine multiple modernities, alternative meta-narratives, and diferent pathways of change that, in Zarakol’s words, will reveal ‘a more open-minded survey of global history’. To take another example of the kind of work that this involves, consider the account of global legal history ofered by Lauren Benton (Chapter 22), which rejects the narrow focus on Western sovereignty contained in Zarakol’s ‘Wrong Answers’, and highlights instead the importance of ‘interpolity zones, or regions marked by interpenetrating power and weak or uneven claims to territorial sovereignty’. We believe that thinking about the relationship between IR and History requires us to understand both traditional state-centric answers to the question of how the distinctively modern international system came into being and developed, and the critical responses from scholars such as Benton (2010) that contest these formulations today and embrace a much wider range of forms of global political ordering. By establishing ‘modernity’ as one of the organizing themes for the Handbook, we hope both to acknowledge its central signifcance in the development of historical IR, and to expose it to radical scrutiny as a limiting factor on our ability to comprehend the complexity of how the international has developed within a global context.

Te second theme tries to unlock the potential for generating fresh insights by adopting diferent framings in geographical space, historical time, and levels of both agency and structure, which we articulate through the idea of granularity. Te sections on ‘Practices’, ‘Locales’, and ‘Moments’ are all intended to ofer opportunities either to step back to contemplate the very broadest kind of analysis, or to zoom in on the personal and micro-political aspects of the day-to-day. An example of the former is Linda and Marsha Frey’s chapter on the practice of diplomacy (Chapter 13), which gives a sweeping survey that runs from the earliest periods of recorded history up to the twentieth century in what one might call the ‘grand manner’ of diplomatic history; whereas for the latter, one could look at Christopher Lee’s analysis of the Bandung Conference (Chapter 47) which homes in on the specifc details of a particular moment, and uses them as a way to think about the wider signifcance of this precise event, and the persistent myths that fowed from it. Tese two chapters ofer almost polar opposites

of the diferent scale on which the encounter between IR and History might be envisaged. In between, our authors adopt a host of diferent perspectives. Several chapters—Eric Selbin’s on ‘Revolution’ (Chapter 26), for example—aim to show how understandings of specifc phenomena can shuttle back and forth between micro- and macro-perspectives.

It is fair to say that ‘Practices’ invites the longue durée, whereas the examination of ‘Moments’ inevitably brings one up close to the personal and the immediate. However, several of our authors break up this expectation. To take just one example, Musab Younis’s fascinating study of the Haitian Revolution (Chapter 39) not only dives into the details of what this moment represents as a specifc event within the historical development of the international politics of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but also uses it as a stimulus to expose ‘the limitations of the very categories we use to measure signifcance and meaning when we study the international’, and concludes by suggesting how an intellectual history of the Haitian revolutionaries’ own self-understandings could be the basis for an alternative perspective on the international grounded in ‘anticolonial and postcolonial cultural nationalism.’ At the same time, somewhat more cautiously, Megan Donaldson’s analysis of the Sykes–Picot agreement of 1916 (Chapter 45) warns about how the question of scale opened up by this granularity theme raises the possibility that something may be lost as we move from one perspective to another, how we can see very diferent things from diferent vantage points, and how indeed some of these may be illusory.

Te section on ‘Locales’ stands, as it were, in between the opposite ends of the spectrum of granularity, and each chapter here gives its author an opportunity to examine the categories that we frequently, and ofen unthinkingly, use to organize discrete subject areas for thinking about historical IR. We think two of these are particularly signifcant: periodization and regionalization. Historians and IR scholars tend to break their subject matter up either into delimited chunks of time (e.g. the ‘early modern’ period, the ‘long nineteenth century’), or into distinct geographical spaces (e.g. the idea of regional international systems in Asia or Africa). Tere is a sense in which these categorizations would not exist, or be so popular, if they did not capture something important and valuable, and so our purpose is not simply to criticize or dismiss these as organizing devices for scholarship. Many of the chapters here, such as Quentin Bruneau’s study of the ‘long nineteenth century’ (Chapter 31), broadly work within this periodization, presenting current scholarship on how it is conceived in History and IR, and sometimes (as in Bruneau’s case) ofering novel interpretive insights into how we should understand it and its place within the wider set of stories of historical IR. Nevertheless, several chapters, such as Zarakol’s chapter on modernity discussed above, or Julia Costa Lopez’s account of the ‘pre-modern’ world (Chapter 27), seek to unsettle these conventional ways of carving up the huge expanse of historical time and geographic space that we are operating within. As Costa Lopez warns, for example, ‘approaching the premodern with periodization-derived preconceptions about its signifcance prevents us from doing anything but confrming our own prejudices—whatever those may be’.

Our choice of specifc ‘Locales’, ‘Practices’, and ‘Moments’ to include in the volume has been guided by our desire both to inform the reader of conventional wisdoms about historical IR, and to challenge these or open up new vistas. For example, among our ‘Locales’ we have a chapter not on the geographical space of Europe as such but on the imaginary of the ‘West’, which (as Jacinta O’Hagan shows in Chapter 29) is the subject of multiple narratives that depict it as variously ‘civilizational’, ‘liberal’, and ‘fragmenting’. Tis highlights the way that we do not simply take regional classifcations as starting points for analysis,

but as socially constructed entities whose meaning needs to be interrogated. As O’Hagan remarks, the ‘West’ is not so much a geographically designated part of the world, but rather it constitutes ‘an imagined community that has acted as a strategic and normative reference point for the constitution of agency and identities in international relations’. Tis clearly connects with and amplifes Zarakol’s point discussed previously, where the understanding of ‘modernity’ in much IR and historical scholarship has traditionally been a vehicle for privileging one view of the ‘Western’ experience of global political ordering at the expense of alternative perspectives.

In a similarly critical vein, while our list of ‘Moments’ acknowledges some that would feature prominently in any textbook, such as the Peace of Westphalia (even if, as Andrew Phillips explains in Chapter 37, much of the signifcance of this moment may be misconceived), we have deliberately tried not to make this just a collection of canonically recognized turning points. Instead, within the obvious limitations in terms of the number of ‘Moments’ we can possibly cover, we have tried to include some where we think that there is a disappointing absence of scholarly connections between historians and IR scholars, such as Dan Green’s examination of the European revolutions of 1848 (Chapter 41). Moreover, mindful of the importance of non-Western agency, we especially want to take the reader to places around the world that might have been missed by the Eurocentric gaze of traditional narratives: we start this section with Jonathan Harris’s study of arguably one of the most globally momentous moments in the shaping of the modern world, the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople (Chapter 36), and carry this forward in chapters such as Younis’s examination of the Haitian Revolution mentioned previously. Of course, we cannot expect these editorial choices alone to redress the balance of what has, or has not, traditionally been included in the scope of historical IR, but we hope that they will ofer a provocation that opens possibilities for new research on times, places, and phenomena that have not received the attention or interpretive weight that they deserve.

The Encounter between History and International Relations

Before we examine some further, deeper aspects of these two themes of modernity and granularity that run throughout the Handbook, we should acknowledge that, in pursuing them, we are building on well-established traditions of scholarship in both the academic disciplines of IR and History. Te two have long been intertwined. From its own side, IR has always been, and continues to be, profoundly infuenced by History. One could argue that many, perhaps even most, of the earliest people who are now recalled as ‘IR theorists’ were historians by training or inclination: for instance, several of the key fgures in the formative period of the IR discipline—such as Raymond Aron, E. H. Carr, and Arnold Toynbee—had close links to History in terms of their academic activities. Tis interest in the history of the international system has been carried forward through the development of the feld in the later-twentieth century by groups such as the ‘English School of International Relations Teory’ (Navari and Green 2014; and see Wight 1977; Bull and Watson 1984; Watson 1992), and a great deal of more recent work across a wide range of IR theory draws inspiration

from historiographical innovations: for example, Duncan Bell shows in Chapter 7 how the feld of international intellectual history has evolved under the infuence of methodological developments such as contextualist approaches to the history of thought; while Chen Yudan applies a similar perspective to the way in which global history impacts on our understanding of the historical sources of international political thought (Chapter 11).

Admittedly, within the last four or fve decades many scholars working within what is ofen described as the mainstream of IR have come to conceive of the feld as an ‘American Social Science’ (Hofmann 1977; see also Crawford and Jarvis 2001), understanding it as an inquiry that is primarily concerned with identifying and explaining timeless recurring patterns of interaction between sovereign states (Waltz 1979). Tis view of how scholarship should proceed is ofen expressed rather combatively, not only as an alternative to, but as a rejection of more historical or normative approaches (for the origins of such controversies, see Singer 1969 and Bull 1969). Nevertheless, even scholars working within this positivist and scientifc self-understanding cannot avoid intrinsically historical questions about when and how modern states came into being, the extent to which their interactions really do display strong continuities over time, and the timing and character of major changes in the institutions and structure of the international system: history is, at the very least, a source of data, and ofen plays a much larger role than that (Elman and Elman 2001 is a good survey). An historical consciousness informs many fundamental works in IR theory (for example, Waltz 1959; Levy 1983; Gilpin 1984; Ruggie 1998; Wagner 2007), and is evident even in some supposedly ‘ahistorical’ theories of neorealism (e.g., Fischer 1992, although criticised for its interpretation of history by Hall and Kratochwil 1993). As Maïa Pal shows in Chapter 5, for those focusing more on economic structures and processes, the history of modern capitalism and its relationship to socialism inevitably looms large from both a historical materialist standpoint and in historical sociology more generally; while Martin Bayly’s chapter on ‘Empire’ (Chapter 14) shows how this remains a relevant unit of analysis despite the Eurocentric insistence on the primacy of sovereignty, and even afer the waves of decolonization of the 1950s and 60s. Scholars today very ofen combine original historical research with new theoretical trends in the study of IR (for example, Teschke 2003; Bell 2007; Fazal 2007; Nexon 2009; Zarakol 2011; MacDonald 2014; Phillips and Sharman 2015; Shilliam 2015; Acharya and Buzan 2019; Owens and Rietzler 2021). Te ‘International History’ section is a growing element of the feld’s major professional body, the International Studies Association.

Te relationship between History and IR is not a one-way street where the latter feeds of the former. Although less frequently or explicitly acknowledged, the discipline of History has been infuenced by trends in the social sciences, including theoretical innovations by IR scholars. Compare, for example, two seminal works in the prestigious Oxford History of Modern Europe series by A. J. P. Taylor (1954) and Paul Schroeder (1994). Te two books may cover contiguous historical periods, but they are a distance apart in terms of the theoretical perspectives and assumptions that underpin them. Taylor’s work is very much a creature of the 1950s, anchored in a straightforward, even trite, version of realism, whereas the intervening 40 years have given Schroeder a wealth of alternative insights into the dynamics of relations between states, many of which are derived from more recent, and arguably more sophisticated variants of realist thought, but extending to entirely diferent theoretical perspectives such as more social constructionist readings of IR as well.

Beyond these intramural developments characteristic of the ongoing dialogue between History and IR, signifcant critical challengers are pushing for major reorientation of both

disciplines. As George Lawson and Jeppe Mulich show in their analysis of ‘Global History and IR’ (Chapter 6), over the last few decades there have been repeated surges of interest in the writing of ‘world’, ‘transnational’ and ‘global histories’ that deliberately attempt to break free from the strait-jackets imposed by nationalist historiography, and ofer intriguing suggestions of links to the study of IR, but ofen also problematizing the state-centrism that colors much work in this area (for example, Bayly 2004; Clavin 2005; Mazlish 2006; Burbank and Cooper 2011; Osterhammel 2014; Conrad 2016). Nivi Manchanda’s study of ‘Race and Racism’ (Chapter 16), or Laura Sjoberg on ‘Gender, History and IR’ (Chapter 8), show how such historical studies are ofen part of eforts to reorient not just units of analysis but entire conceptual vocabularies to account for previously excluded, subaltern voices (e.g. Fischer 2004; Getachew 2019; Pham and Shilliam 2016). Teoretical orientations such as historical materialism, historical institutionalism, post-structuralism, and postcolonialism have shaped and reshaped how history is studied, and whose history ought to be studied: as well as Pal’s chapter on historical sociology here, one could also point to Zeynep Gulsah Capan’s study of postcolonial histories and their place in IR (Chapter 9). Critical assessments regarding what constitutes a ‘source’ and an ‘archive’, such as the powerful challenge posed by the scholar (in an anthropology department no less) Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1995) and taken up by those seeking to uncover and challenge the persistence of white supremacy in academia, have begun to transform the way in which History is practiced. Tis in turn destabilizes how scholars view the workings of the ‘international system’, and indeed how they understand the very meaning and signifcation of that term and associated ideas within the IR feld (see, for instance, Schmidt 1998; Vitalis 2015; Spruyt 2020).

Such critiques reveal that interdisciplinary entanglements may just as easily reify and replicate persistent patterns of exclusion and omission as move either or both disciplines forward. For example, while the members of the ‘English school’ are ofen cast as defenders of an historical approach to IR, the growing challenges to their historiography regarding the so-called ‘expansion of international society’ (Bull and Watson 1984) as a narrative of progressive evolution of the international system suggest that any narrative framing of historical evidence for theoretical purposes, or generation of theoretical insights from historical narrations, may become fodder for deep critiques of the omissions and silences thus facilitated (Keene 2014; Howland 2016; Dunne and Reus-Smit 2017). Moreover, during a time of political upheaval in what had long been considered the relatively stable ‘West’, the study of History itself has become intensely politicized and subject to backlash, with historical monuments sometimes being literally pushed of their pedestals even as people band together to ofer new defenses of old myths, all in a climate of intense pressure on existing democratic and semi-democratic institutions. Te space that brings IR and History together is thus not simply a place for collaborative mutual learning, but can be a battlefeld where bitterly opposed intellectual commitments confront one another.

What remains clear in all this turmoil is that it is inadequate to reify History and IR as independent felds of enquiry, each of which has its own proprietary terrain, with a set of questions, issues, and methods that belong to it exclusively. Tese are not closed guilds, much as they may at times seem that way to scholars struggling to articulate new ideas in a climate where secure academic positions are few and the weight of expectations ofen induces conformity with established practice, and where professional opportunities can be jealously guarded for students with a degree in the ‘right’ subject. It is thus with a certain humility and awareness of the contentiousness of our analytical categories, as well as of

the power dynamics involved in articulating both historical and theoretical agendas, that this volume has sought to bring together writers from both History and IR. Tis awareness also informs our editorial decision to ask them to orient their contributions according to the two very broad organizing themes or concepts that we outlined at the beginning of this Introduction: modernity and granularity. We want to conclude these introductory remarks by explaining in more detail why we think these ofer fertile sources of questions shared across the disciplines, and give the chance to integrate them in productive ways without, we hope, either ignoring what long traditions of scholarship can provide, or closing of the potential for radical critique.

Modernity

‘Modernity’ is an almost inescapable category for imagining historical time, especially with its rich variety of adjectival modifers, ‘pre’, ‘early’, ‘high’, ‘late’, ‘post’, and so on. One might think of the similar role that ‘democracy with adjectives’ plays in organizing contemporary political science (Collier and Levitsky 1997), and it is not coincidental that the concept of ‘capitalism’ can be adapted in much the same ways. Yet, perhaps in part because of its ubiquity, modernity will always be a moving target, and a contested one. Te use of the term in ordinary language ofen serves to distinguish what is distinctively new in the ‘present’ in relation to what was the ‘past’. But precisely because of this—because human beings draw such distinctions with respect to everything from fashion to architecture to ideology to modes of political and economic organization—the question of modernity constitutes a productive forum for historians and IR scholars, among others (and there is much to be said for broader cross-fertilization than just History and IR; many contributions in this volume are more interdisciplinary than that if one begins to look closely at sources).

As we noted at the beginning of the Introduction, and in our brief discussion of Ayse Zarakol’s contribution to this volume on this specifc topic (Chapter 28), we do not intend modernity to imply a single linear narrative that is to be imposed on a given topic. We do not insist that modernity is the fscal-military or bureaucratic state, the market, property, or some such form of social or political organization, and that the question of modernity requires us simply to track the emergence of one or a few of these at diferent times in diferent parts of the world. On the contrary, while acknowledging that these are signifcant themes, we see modernity as presenting a series of puzzles and provocations that can be taken as an invitation to open-ended intellectual inquiry, and even playfulness. How have diferent people conceptualized what it means to be ‘modern’? Against what do we distinguish it, what lies outside of the modern: the ancient? Te medieval? Te primitive? Te traditional? Te contemporary? Te non-Western? How do we time the modern; and where and in what confguration of forces do we locate the builders of modernity? Whose modernity are we analysing, and are those who resist or are diferent merely peripheral, or lef out of modernity altogether? What does it take to opt out of modernity, if that is even possible? To the extent that intellectual historians have identifed modernity with something like the ‘Enlightenment’, what is the relationship between the development of ideas and culture on the one hand, and the development and maturation of social, political, and economic structures and practices on the other? What is at stake in the question of whether we should

consider modernity as a single overall phenomenon or set of structures, or whether in the postcolonial moment we need to consider ‘multiple modernities’?

Te question of what modernity is and what it does to our understanding of the international thus strikes us as an interesting way to integrate intellectual and political histories, and to highlight common preoccupations as well as salient diferences between the disciplines of IR and History. Although some IR scholars may set History aside in their preoccupation with what they take to be the timeless condition of anarchy, and in some cases those who model the subject in terms of rational actors with given sets of interests opt to bracket questions about the historical development of such interests, we are hardly alone in arguing that a productive way to comprehend IR is in terms of the historical development of the forms of actors, institutions, modes of production, and both strategic and normative principles and practices with which we live today (for example, Rosenberg 1994). Such a focus does not neglect but indeed raises interesting questions about the continuity of social forms through time, considering whether a history should look like an evolutionary narrative or something more akin to genealogies of contemporary phenomena, such as nation-states or security dilemmas. But clearly a focus on the historical development of, say, modern statehood, also raises questions about change, in the sense of the identifcation of moments of profound discontinuity or transformation. How did the international order that we live in come to be, and what is distinctive about it in comparison with ways of conducting ‘international relations’ outside the scope of what is identifed as modernity?

Timing modernity involves not only looking at continuities and distinctions between ‘past’ and ‘present’, and hence the identifcation of the ‘pre-modern’, as in Costa Lopez’s chapter mentioned previously; articulations of ‘the modern’ entail visions of a future as well. Visions of a fully modernized or even post-modern future extrapolate from readings of how certain pasts generated a given present, and how such trends bode for future confgurations of world politics. For example, a prominent theme in Lucien Ashworth’s chapter on ‘Liberal Progressivism and International History’ (Chapter 4), and in Or Rosenboim and Chika Tonooka’s study of how the specifc terms of the ‘international’ and ‘the global’ were reimagined in the twentieth century (Chapter 35), is how a liberal reading of international history envisions a future populated by liberal democratic states linked together by shared legal constraints on the use of force as well as by more or less freely circulating commercial and fnancial fows. And, as demonstrated in key works focusing on imperialism and postcolonial world politics, historical inquiry serves to shape not only how we narrate the past; a particular narration of the past may constitute a critical intervention in present-day politics, as well as articulating a specifc vision of the future (for example, Scott 2004; Wilder 2015; Getachew 2019; Spruyt 2020). Such interventions remind students of international politics that visions of the future constitute fodder for critical reinterpretation as the kinds of questions we ask about contemporary world politics change. Far from being only about ‘the past’, therefore, readings of history speak to the present and also shape visions of the future. As they are played out in the contemporary discipline, questions about timing modernity in IR ofen focus on how to pin-point the most signifcant discontinuities that shaped the ‘modern’ international system in the form of what Barry Buzan and George Lawson have called ‘benchmark dates’ (Buzan and Lawson 2014). In the past these debates were ofen quite open, with scholars looking back to events such as the Council of Constance or the French intervention in the Italian wars in 1494 (which supposedly spread ideas about raison d’etat and balance of power around Europe). However, R. B. J. Walker’s analysis of ‘origin

myths’ in the IR discipline (Chapter 2) shows how in more recent years the IR feld has coalesced around a (still-controversial) origin story pivoted on the Peace of Westphalia of 1648. While we think it is worthwhile to look in detail at this specifc moment, as Andrew Phillips does in Chapter 37, neither we nor Phillips want to subscribe to an over-simplifed, and frankly somewhat dubious, story about the ‘Westphalian moment’ as the key turningpoint when a principle of territorial sovereignty was frst established as the basis of the modern form of world order (see Keene 2002; Teschke 2003; Beaulac 2004). Our selection of ‘Moments’ in Part 4 of the Handbook is not an attempt to present a list of possible candidate benchmark dates, but is intended in part to allow opportunities to refect on diferent key instances of discontinuity that might feature in such a story, and so to explore alternatives to the Westphalian starting point.

Putting the historical discontinuities of modernity, rather than the supposedly timeless logic of anarchy, at the heart of our enquiry also raises the question of where the international system originated. Interwoven with chronological questions about periodization are geographical questions about social networks and connections that have traditionally been— but are no longer—pushed aside by an ofen silent assumption of Eurocentrism (the locus classicus for these discussions is Wight 1977, chapters 4 and 5; see also Bentley 1996). Where there once may have been a general consensus about modernity originating in Europe with the European states-system, research in recent decades has shaken this consensus and brought some of its assumptions and omissions under scrutiny. At the very least, the idea of a European system as somehow self-contained demonstrates an inexcusable neglect of the central role of imperial expansion and colonization projects as contributors to Europe’s development.

Tere may be no consensus on when the ‘modern’ international system began, nor how far it has spread, nor indeed whether some regions have already passed through to the ‘post-modern,’ or followed some diferent path altogether. Modernity therefore has the advantage of ofering a common frame of reference without closing of debates about its geographic or temporal boundaries, nor indeed about what forms of political order ought to be associated with it. We can thus engage questions about the shif from the medieval to the modern international system; or, as David Kang does in the chapter on ‘ “Asia” in the History of IR’ (Chapter 34), about the question of ‘modernization’ in Asia, for example, without presupposing that we already know the answers. We can inquire as to the origin, transmission, and circulation of modernity’s core concepts and practices without assuming that modernity belongs to a particular place (Europe) or even time (for example Hobson 2004). While modernity must have some boundaries to render it a coherent organizational concept, we do not presume a priori agreement on where those boundaries are located, either in space or time. Te contributions to this volume ofer a diversity of ways by which modernity may be timed and placed, and especially in Part 3 on ‘Locales’ we have encouraged our authors to think about the concept from the perspective of diferent regions or parts of the world, and historical periods (themselves, we acknowledge, ofen socially constructed artifacts of modernity).

Authority to determine and claim modernity can itself be contested, as can the contours of what may be termed modern and what ‘backward’. As Yongjin Zhang shows, one of the main ways in which modern forms of empire rationalized their exception to the principle of the recognition of territorial sovereignty was precisely in terms of a heavily loaded distinction between ‘civilization’ and ‘barbarism’ (Chapter 15). Another key example of such