The Humanistic Tradition Volume 1: Prehistory to the Early Modern World 7th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-humanistictradition-volume-1-prehistory-to-the-early-modernworld-7th-edition-ebook-pdf/ Download more ebook from https://ebookmass.com

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

The Humanistic Tradition Volume 2: The Early Modern World to the Present 7th Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-humanistic-traditionvolume-2-the-early-modern-world-to-the-present-7th-edition-ebookpdf-version/

World Civilizations: The Global Experience, Volume 1 7th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/world-civilizations-the-globalexperience-volume-1-7th-edition-ebook-pdf/

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory 14th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/people-of-the-earth-anintroduction-to-world-prehistory-14th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition, Reissued Edition, Volume 1 8th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/jansons-history-of-art-the-westerntradition-reissued-edition-volume-1-8th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Making Empire : Ireland, Imperialism, and the Early Modern World Jane Ohlmeyer

https://ebookmass.com/product/making-empire-ireland-imperialismand-the-early-modern-world-jane-ohlmeyer/

World Prehistory: A Brief Introduction 9th Edition –Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/world-prehistory-a-briefintroduction-9th-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

The Oxford History of Life-Writing, Volume 2: Early Modern Alan Stewart

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-history-of-life-writingvolume-2-early-modern-alan-stewart/

Early Education Curriculum: A Childu2019s Connection to the World [Print Replica] (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/early-education-curriculum-achilds-connection-to-the-world-print-replica-ebook-pdf/

World Civilizations Volume 1: To 1700 8th Edition

Philip J. Adler

https://ebookmass.com/product/world-civilizationsvolume-1-to-1700-8th-edition-philip-j-adler/

Western Sudan: Nok Culture 61

LOOKING BACK 61

Glossary 62

3 India, China, and the

Americas (ca. 3500–500 B.C.E.) 63

LOOKING AHEAD 64

Ancient India 64

Indus Valley Civilization (ca. 2700–1500 B C E.) 64

The Vedic Era (ca. 1500–500 B.C.E.) 64

Hindu Pantheism 65

EXPLORING ISSUES The “Out of India” Debate 66

The Bhagavad-Gita 66

READING 3.1 From the Bhagavad-Gita 66

Ancient China 67

The Shang Dynasty (ca. 1766–1027 B C E.) 68

The Western Zhou Dynasty (1027–771 B C E.) 70

Spirits, Gods, and the Natural Order 70

The Chinese Classics 71

Daoism 72

READING 3.2 From the Dao de jing 72

The Americas 72

Ancient Peru 72

MAKING CONNECTIONS 73

The Olmecs 74

LOOKING BACK 75

Glossary 75

4 Greece: Humanism and the Speculative Leap

(ca. 3000–332 B.C.E.) 76

LOOKING AHEAD 77

Bronze Age Civilizations of the Aegean (ca. 3000–1200 B.C.E.) 77

Minoan Civilization (ca. 2000–1400 B C E.) 78

MAKING CONNECTIONS 79

Mycenaean Civilization (ca. 1600–1200 B C E.) 80

The Heroic Age (ca. 1200–750 B C E.) 80

READING 4.1 From the Iliad 82

The Greek Gods 85

The Greek City-State and the Persian Wars (ca. 750–480 B C E.) 86

Herodotus 87

Athens and the Greek Golden Age (ca. 480–430 B C E.) 87

Pericles’ Glorification of Athens 88

READING 4.2 From Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War 88

The Olympic Games 90

The Individual and the Community 90

Greek Drama 90

The Case of Antigone 92

READING 4.3 From Sophocles’ Antigone 92

Aristotle on Tragedy 99

READING 4.4 From Aristotle’s Poetics 99

Greek Philosophy: The Speculative Leap 100

Naturalist Philosophy: The Pre-Socratics 100

Pythagoras 100

Hippocrates 101

Humanist Philosophy 101

The Sophists 101

Socrates and the Quest for Virtue 101

READING 4.5 From Plato’s Crito 103

Plato and the Theory of Forms 104

READING 4.6 From the “Allegory of the Cave” from Plato’s Republic 105

Plato’s Republic: The Ideal State 108

Aristotle and the Life of Reason 108

Aristotle’s Ethics 109

READING 4.7 From Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 109

Aristotle and the State 111

LOOKING BACK 111

Glossary 112

5 The Classical Style (ca. 700–30 B.C.E.) 113

LOOKING AHEAD 114

The Classical Style 114

READING 5.1 From Vitruvius’ Principles of Symmetry 114

Humanism, Realism, and Idealism 116

The Evolution of the Classical Style 117

Greek Sculpture: The Archaic Period (ca. 700–480 B C E.) 117

MAKING CONNECTIONS 118

Greek Sculpture: The Classical Period (480–323 B C E.) 118

The Classical Ideal: Male and Female 120

LOOKING INTO The Parthenon 122

Greek Architecture: The Parthenon 123

The Sculpture of the Parthenon 124

EXPLORING ISSUES The Battle Over Antiquities 125

The Gold of Greece 127

The Classical Style in Poetry 127

READING 5.2 The Poems of Sappho 128

READING 5.3 From Pindar’s Odes 128

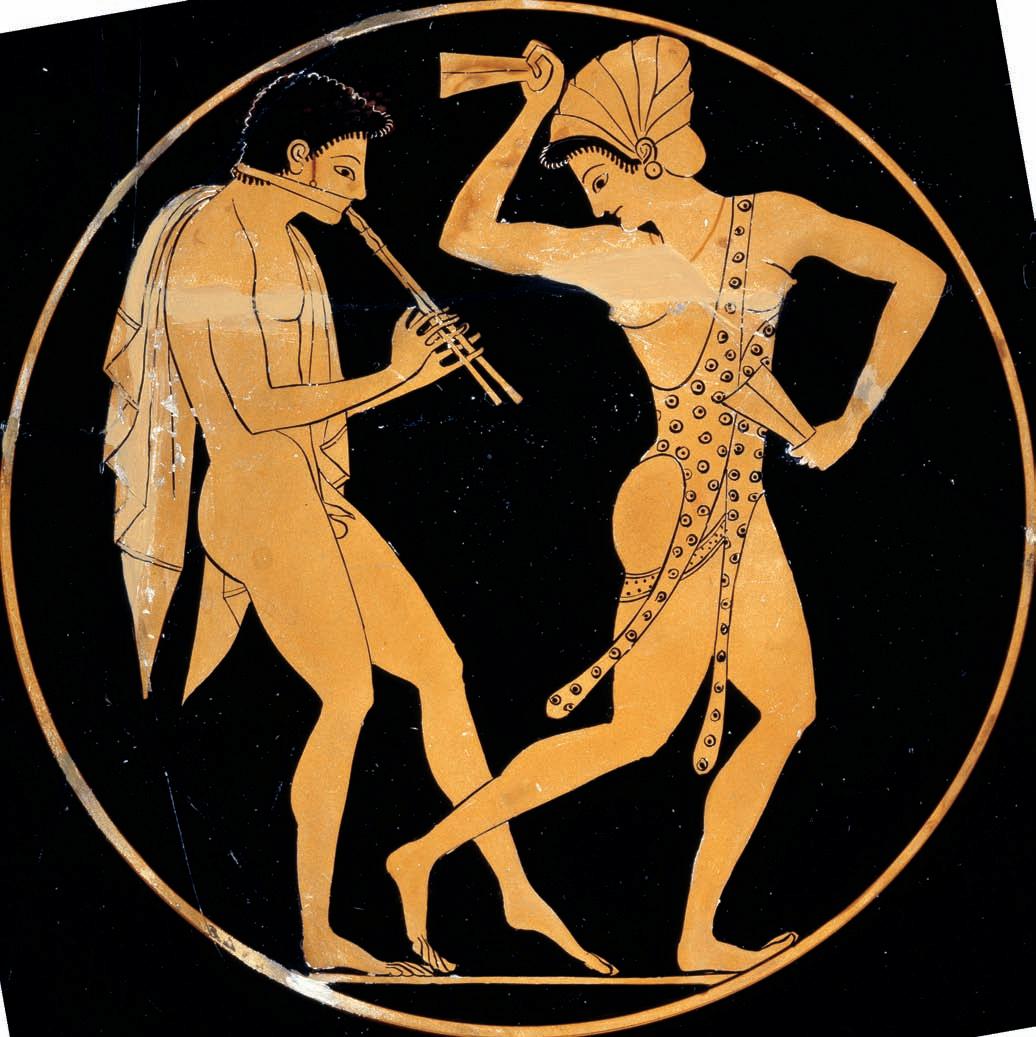

The Classical Style in Music and Dance 129

The Diffusion of the Classical Style: The Hellenistic Age (323–30 B C E.) 130

Hellenistic Schools of Thought 132

Hellenistic Art 132

LOOKING BACK 135

Glossary 136

6 Rome: The Rise to Empire (ca. 1000 B.C.E.–476 C.E.) 137

LOOKING AHEAD 138

The Roman Rise to Empire 138

Rome’s Early History 138

The Roman Republic (509–133 B.C.E.) 139

READING 6.1 Josephus’ Description of the Roman Army 140

The Collapse of the Republic (133–30 B C E.) 141

The Roman Empire (30 B C E.–180 C E.) 141

Roman Law 143

The Roman Contribution to Literature 143

Roman Philosophic Thought 143

READING 6.2 From Seneca’s On Tranquility of Mind 144

Latin Prose Literature 145

READING 6.3 From Cicero’s On Duty 145

READING 6.4 From Tacitus’ Dialogue on Oratory 146

Roman Epic Poetry 146

READING 6.5 From Virgil’s Aeneid (Books Four and Six) 147

Roman Lyric Poetry 148

READING 6.6 The Poems of Catullus 148

The Poems of Horace 149

READING 6.7 The Poems of Horace 149

The Satires of Juvenal 150

READING 6.8A From Juvenal’s “Against the City of Rome” 150

READING 6.8B From Juvenal’s “Against Women” 151

Roman Drama 152

The Arts of the Roman Empire 152

Roman Architecture 152

MAKING CONNECTIONS 156

Roman Sculpture 160

Roman Painting and Mosaics 163

Roman Music 164

The Fall of Rome 165

LOOKING BACK 166

Glossary 166

7 China: The Rise to Empire (ca. 770 B.C.E.–220 C.E.) 167

LOOKING AHEAD 168

Confucius and the Classics 168

The Eastern Zhou Dynasty (ca. 771–256 B C E.) 168

READING 7.1 From the Analects of Confucius 169

Confucianism and Legalism 170

The Chinese Rise to Empire 170

The Qin Dynasty (221–206 B C E.) 170

The Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.) 171

The Literary Contributions of Imperial China 174

Chinese Prose Literature 174

READING 7.2 From Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian 174

Chinese Poetry 175

READING 7.3 A Selection of Han Poems 176

The Visual Arts and Music 176

LOOKING BACK 180

Glossary 180

BOOK 2

Medieval Europe and the World Beyond

8 A Flowering of Faith: Christianity and Buddhism (ca. 400 B.C.E.–300 C.E.) 183

LOOKING AHEAD 184

The Background to Christianity 184

The Greco-Roman Background 184

The Near Eastern Background 184

READING 8.1 From Apuleius’ Initiation into the Cult of Isis 185

The Jewish Background 186

The Rise of Christianity 187

The Life of Jesus 187

The Message of Jesus 188

READING 8.2 From the Gospel of Matthew 188

The Teachings of Paul 190

READING 8.3 From Paul’s Epistle to the Church in Rome 190

EXPLORING ISSUES The Gnostic Gospels 191

The Spread of Christianity 192

The Rise of Buddhism 192

The Life of the Buddha 192

The Message of the Buddha 193

READING 8.4A From the Buddha’s Sermon at Benares 194

READING 8.4B From the Buddha’s Sermon on Abuse 195

The Spread of Buddhism 195

Buddhism in China and Japan 196

LOOKING BACK 197

Glossary 197

9 The Language of Faith: Symbolism and the Arts (ca. 300–600 C.E.) 198

LOOKING AHEAD 199

The Christian Identity 199

READING 9.1 The Nicene Creed 200

Christian Monasticism 200

The Latin Church Fathers 200

READING 9.2 Saint Ambrose’s “Ancient Morning Hymn” 201

READING 9.3 From Saint Augustine’s Confessions 201

Augustine’s City of God 203

READING 9.4 From Saint Augustine’s City of God Against the Pagans 203

Symbolism and Early Christian Art 204

Early Christian Architecture 206

LOOKING INTO The Murano Book Cover 207

Iconography of the Life of Jesus 209

Byzantine Art and Architecture 210

The Byzantine Icon 215

Early Christian Music 216

The Buddhist Identity 216

Buddhist Art and Architecture in India 216

Buddhist Art and Architecture in China 221

Buddhist Music 223

LOOKING BACK 224

Glossary 225

10 The Islamic World: Religion and Culture (ca. 570–1300) 226

LOOKING AHEAD 227

The Religion of Islam 227

Muhammad and Islam 227

Submission to God 229

The Qur’an 229

The Five Pillars 229

EXPLORING ISSUES Translating the Qur’an 230

READING 10.1 From the Qur’an 230

The Muslim Identity 233

The Expansion of Islam 233 Islam in Africa 233

Islam in the Middle East 234

Islamic Culture 235

Scholarship in the Islamic World 235

Islamic Poetry 236

READING 10.2 Secular Islamic Poems 237

Sufi Poetry 238

READING 10.3 The Poems of Rumi 238

Islamic Prose Literature 240

READING 10.4 From The Thousand and One Nights 240

Islamic Art and Architecture 243

Music in the Islamic World 246

LOOKING BACK 247

Glossary 248

11 Patterns of Medieval Life (ca. 500–1300) 249

LOOKING AHEAD 250

The Germanic Tribes 250

Germanic Law 251

Germanic Literature 251

READING 11.1 From Beowulf 252

Germanic Art 253

MAKING CONNECTIONS 254

Charlemagne and the Carolingian Renaissance 255

The Abbey Church 258

Early Medieval Culture 258

Feudal Society 258

The Literature of the Feudal Nobility 260

READING 11.2 From the Song of Roland 260

The Norman Conquest and the Arts 262

The Bayeux Tapestry 264

The Lives of Medieval Serfs 264

High Medieval Culture 266

The Christian Crusades 266

The Medieval Romance and the Code of Courtly Love 267

READING 11.3 From Chrétien de Troyes’ Lancelot 268

The Poetry of the Troubadours 271

READING 11.4 Troubadour Poems 272

The Origins of Constitutional Monarchy 273

The Rise of Medieval Towns 273

LOOKING BACK 274

Glossary 275

12 Christianity and the Medieval Mind

(ca. 1000–1300) 276

LOOKING AHEAD 277

The Medieval Church 277

The Christian Way of Life and Death 277

EXPLORING ISSUES The Conflict Between Church and State 278

The Franciscans 278

READING 12.1 Saint Francis’ The Canticle of Brother Sun 279

Medieval Literature 279

The Literature of Mysticism 279

READING 12.2 From Hildegard of Bingen’s Know the Ways of the Lord 280

Sermon Literature 281

READING 12.3 From Pope Innocent III’s On the Misery of the Human Condition 282

The Medieval Morality Play 283

READING 12.4 From Everyman 283

Dante’s Divine Comedy 286

READING 12.5 From Dante’s Divine Comedy 290

The Medieval University 294

Medieval Scholasticism 295

Thomas Aquinas 296

READING 12.6 From Aquinas’ Summa Theologica 297

LOOKING BACK 298

Glossary 298

13 The Medieval Synthesis in the Arts (ca. 1000–1300) 299

LOOKING AHEAD 300

The Romanesque Church 300

LOOKING INTO A Romanesque Last Judgement 304

Romanesque Sculpture 305

MAKING CONNECTIONS 306

The Gothic Cathedral 307

Gothic Sculpture 312

MAKING CONNECTIONS 314

Stained Glass 315

The Windows at Chartres 316

Sainte-Chapelle: Medieval “Jewelbox” 317

Medieval Painting 318

Medieval Music 320

Early Medieval Music and Liturgical Drama 320

Medieval Musical Notation 321

Medieval Polyphony 321

The “Dies Irae” 321

The Motet 322

Instrumental Music 323

LOOKING BACK 323

Glossary 324

14 The World Beyond the West: India, China, and Japan (ca.

LOOKING AHEAD 326

India 326

Hinduism 327

500–1300) 325

LOOKING INTO Shiva: Lord of the Dance 328

Indian Religious Literature 329

READING 14.1 From the Vishnu Purana 329

Indian Poetry 330

READING 14.2 From The Treasury of Well-Turned Verse 330

Indian Architecture 330

Indian Music and Dance 332

China 333

China in the Tang Era 333

Confucianism 336

Buddhism 336

China in the Song Era 337

Technology in the Tang and Song Eras 338

Chinese Literature 339

Chinese Music and Poetry 339

READING 14.3 Poems of the Tang and Song Eras 340

Chinese Landscape Painting 341

MAKING CONNECTIONS 342

Chinese Crafts 343

Chinese Architecture 344

Japan 345

READING 14.4 From The Diary of Lady Murasaki 346

Buddhism in Japan 347

MAKING CONNECTIONS 349

The Age of the Samurai: The Kamakura Shogunate (1185–1333) 350

No¯ Drama 352

READING 14.5 From Zeami’s Kadensho 353

LOOKING BACK 353

Glossary 354

BOOK 3

The

European Renaissance, the Reformation, and Global Encounter

15 Adversity and Challenge: The Fourteenth-Century Transition (ca. 1300–1400) 357

LOOKING AHEAD 358

Europe in Transition 358

The Hundred Years’ War 358

The Decline of the Church 359

Anticlericalism and the Rise of Devotional Piety 360

The Black Death 360

READING 15.1 From Boccaccio’s Introduction to the Decameron 361

The Effects of the Black Death 363

Literature in Transition 364

The Social Realism of Boccaccio 364

READING 15.2 From Boccaccio’s “Tale of Filippa” from the Decameron 364

The Feminism of Christine de Pisan 365

READING 15.3 From Christine de Pisan’s Book of the City of Ladies 365

The Social Realism of Chaucer 367

READING 15.4 From Chaucer’s “Prologue” and “The Miller’s Tale” in the Canterbury Tales 368

Art and Music in Transition 369

Giotto’s New Realism 369

MAKING CONNECTIONS 369

Devotional Realism and Portraiture 370

The Ars Nova in Music 373

LOOKING BACK 375

Glossary 375

16 Classical Humanism in the Age of the Renaissance (ca. 1300–1600) 376

LOOKING AHEAD 377

Italy: Birthplace of the Renaissance 377

The Medici 378

Classical Humanism 379

Petrarch: “Father of Humanism” 380

READING 16.1 From Petrarch’s Letter to Lapo da Castiglionchio 381

LOOKING INTO Petrarch’s Sonnet 134 382

Civic Humanism 383

Alberti and Renaissance Virtù 383

READING 16.2 From Alberti’s On the Family 384

Ficino: The Platonic Academy 385

Pico della Mirandola 385

READING 16.3 From Pico’s Oration on the Dignity of Man 385

Castiglione: The Well-Rounded Person 387

READING 16.4 From Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier 388

Renaissance Women 390

Women Humanists 391

Lucretia Marinella 391

READING 16.5 From Marinella’s The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men 392

Machiavelli 394

READING 16.6 From Machiavelli’s The Prince 395

LOOKING BACK 397

Glossary 397

17 Renaissance Artists: Disciples of Nature, Masters of Invention (ca. 1400–1600) 398

LOOKING AHEAD 399

Renaissance Art and Patronage 399

The Early Renaissance 399

The Revival of the Classical Nude 399

MAKING CONNECTIONS 401

Early Renaissance Architecture 402

The Renaissance Portrait 405

Early Renaissance Artist–Scientists 408

EXPLORING ISSUES Renaissance Art and Optics 408

Masaccio 409

Ghiberti 412

Leonardo da Vinci as Artist–Scientist 413

READING 17.1 From Leonardo da Vinci’s Notes 414

The High Renaissance 415

Leonardo 415

READING 17.2 From Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Architects, and Sculptors 415

EXPLORING ISSUES The Last Supper: Restoration or Ruin? 416

Raphael 417

LOOKING INTO Raphael’s School of Athens 418

Architecture of the High Renaissance: Bramante and Palladio 420

Michelangelo and Heroic Idealism 421

The High Renaissance in Venice 428

Giorgione and Titian 429

The Music of the Renaissance 430

Early Renaissance Music: Dufay 431

The Madrigal 431

High Renaissance Music: Josquin 432

Women and Renaissance Music 432

Instrumental Music of the Renaissance 432

Renaissance Dance 434

LOOKING BACK 434

Glossary 435

18 Cross-Cultural Encounters: Asia, Africa, and the Americas (ca. 1300–1600) 436

LOOKING AHEAD 437

Global Travel and Trade 437

China’s Treasure Ships 437

European Expansion 437

The African Cultural Heritage 440

Ghana 441

Mali and Songhai 441

Benin 442

The Arts of Africa 442

Sundiata 442

READING 18.1 From Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali 443

African Myths and Proverbs 446

READING 18.2 Three African Myths on the Origin of Death 446

African Poetry 446

READING 18.3 Selections from African Poetry 447

African Music and Dance 448

The African Mask 448

MAKING CONNECTIONS 449

African Sculpture 450

EXPLORING ISSUES African Wood Sculpture: Text and Context 451

African Architecture 451

Cross-Cultural Encounter 451

Ibn Battuta in West Africa 451

READING 18.4 From Ibn Battuta’s Book of Travels 452

The Europeans in Africa 453

The Americas 454

Native American Cultures 454

Native North American Arts: The Northwest 456

Native North American Arts: The Southwest 456

READING 18.5 “A Prayer of the Night Chant” (Navajo) 458

Native American Literature 458

READING 18.6 Two Native American Tales 459

The Arts of Meso- and South America 460

Early Empires in the Americas 461

The Maya 461

The Inca 463

The Aztecs 464

EXPLORING ISSUES The Clash of Cultures 466

Cross-Cultural Encounter 466

The Spanish in the Americas 466

READING 18.7 From Cortés’ Letters from Mexico 467

The Aftermath of Conquest 468

The Columbian Exchange 470

LOOKING BACK 470

Glossary 471

19 Protest and Reform: The Waning of the Old Order (ca. 1400–1600) 472

LOOKING AHEAD 473

The Temper of Reform 473

The Impact of Technology 473

Christian Humanism and the Northern Renaissance 474

The Protestant Reformation 475

READING 19.1 From Luther’s Address to the German Nobility 476

The Spread of Protestantism 477

Calvin 477

EXPLORING ISSUES Humanism and Religious

Fanaticism: The Persecution of Witches 478

The Anabaptists 478

The Anglican Church 478

Music and the Reformation 479

Northern Renaissance Art 479

Jan van Eyck 479

LOOKING INTO Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Double Portrait 480

Bosch 481

Printmaking 484

Dürer 484

Grünewald 485

Cranach and Holbein 486

Bruegel 487

Sixteenth-Century Literature 488

Erasmus: The Praise of Folly 488

READING 19.2 From Erasmus’ The Praise of Folly 489

More’s Utopia 490

READING 19.3 From More’s Utopia 491

Cervantes: Don Quixote 492

READING 19.4 From Cervantes’ Don Quixote 492

Rabelais and Montaigne 494

READING 19.5 From Montaigne’s On Cannibals 494

Shakespeare 496

Shakespeare’s Sonnets 497

READING 19.6 From Shakespeare’s Sonnets 497

The Elizabethan Stage 497

Shakespeare’s Plays 499

Shakespeare’s Hamlet 500

READING 19.7 From Shakespeare’s Hamlet 500

Shakespeare’s Othello 502

READING 19.8 From Shakespeare’s Othello 502

LOOKING BACK 504

Glossary 504

Picture Credits 505

Literary Credits 507

Index 509

MAPS

0.1 Ancient River Valley Civilizations 9

1.1 Mesopotamia, 3500–2500 B.C.E. 18

2.1 Ancient Egypt 45

3.1 Ancient India, ca. 2700–1500 B C E 64

3.2 Ancient China 67

4.1 Ancient Greece, ca. 1200–332 B C E 77

5.1 The Hellenistic World 131

6.1 The Roman Empire in 180 C E. 138

7.1 Han and Roman Empires, ca. 180 C E 173

9.1 The Byzantine World Under Justinian, 565 211

10.1 The Expansion of Islam, 622–ca. 750 227

11.1 The Early Christian World and the Barbarian Invasions, ca. 500 250

11.2 The Empire of Charlemagne, 814 255

11.3 The Christian Crusades, 1096–1204 267

13.1 Romanesque and Gothic Sites in Western Europe, ca. 1000–1300 301

14.1 India in the Eleventh Century 326

14.2 East Asia, ca. 600–1300 334

16.1 Renaissance Italy, 1300–1600 377

18.1 World Exploration, 1271–1295; 1486–1611 439

18.2 Africa, 1000–1500 440

18.3 The Americas Before 1500 455

19.1 Renaissance Europe, ca. 1500 474

MUSIC LISTENING SELECTIONS

Anonymous, “Epitaph for Seikilos,” Greek, ca. 50 C E 129

Gregorian chant, “Alleluya, vidimus stellam,” codified 590–604 216

Buddhist chant, Morning prayers (based on the Lotus Scripture) at Nomanji, Japan, excerpt 223 Islamic Call to Prayer 246

Anonymous, Twisya No. 3 of the Nouba 247 Bernart de Ventadour, “Can vei la lauzeta mouver” (“When I behold the lark”), ca. 1150, excerpt 271 Medieval liturgical drama, The Play of Daniel, “Ad honorem tui, Christe,” “Ecce sunt ante faciem tuam” 320

Hildegard of Bingen, O Successores (“Your Successors”), ca. 1150 321

Two examples of early medieval polyphony: parallel organum, “Rex caeli, Domine,” excerpt; melismatic organum, “Alleluia, Justus ut palma,” ca. 900–1150, excerpts 321

Pérotin, three-part organum, “Alleluya” (Nativitas), twelfth century 321

Anonymous, motet, “En non Diu! Quant voi; Eius in Oriente,” thirteenth century, excerpt 322

French dance, “Estampie,” thirteenth century 323 Indian music, Thumri, played on the sitar by Ravi Shankar 332

Chinese music: Cantonese music drama for male solo, zither, and other musical instruments, “Ngoh wai heng kong” (“I’m Mad About You”) 339

Machaut, Messe de Notre Dame (Mass of Our Lady), “Ite missa est, Deo gratias,” 1364 374

Anonymous, English round, “Sumer is icumen in,” fourteenth century 374

Guillaume Dufay, Missa L’homme armé (The Armed Man Mass), “Kyrie I,” ca. 1450 431

Roland de Lassus (Orlando di Lasso), madrigal, “Matona, mia cara” (“My lady, my beloved”), 1550 431

Thomas Morley, madrigal, “My bonnie lass she smileth,” 1595 432

Josquin des Prez, motet, “Tulerunt Dominum meum,” ca. 1520 432

Music of Africa, Senegal, “Greetings from Podor” 448

Music of Africa, Angola, “Gangele Song” 448

Music of Native America, “Navajo Night Chant,” male

chorus with gourd rattles 458

ANCILLARY READING SELECTIONS

The Israelites’ Relations with Neighboring Peoples from the Hebrew Bible (Kings) 34

On Good and Evil from The Divine Songs of Zarathustra 41

Harkhuf’s Expeditions to Nubia 60

From the Ramayana 65

On the Origin of the Castes from the Rig Veda 65

On Hindu Tradition from the Upanishads 65

Family Solidarity in Ancient China from the Book of Songs 71

From the Odyssey 81

The Creation Story from Hesiod’s Theogony 85

From Aeschylus’ Agamemnon 92

From Euripides’ Medea 92

From Aristophanes’ Lysistrata 92

From Sophocles’ Oedipus the King 92

Ashoka as a Teacher of Humility and Equality from the Ashokavadana 195

Iraq in the Late Tenth Century from Al-Muqaddasi’s The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Region 234

From Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine 235

From Dante’s Paradiso 287

The Arab Merchant Suleiman on Business Practices in Tang China 334

Du Fu’s “A Song of War Chariots” 340

From the Travels of Marco Polo 437

King Afonso I Protests Slave Trading in the Kingdom of Congo 453

From Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion 477

From Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel 494

From Shakespeare’s Henry V 499

From Shakespeare’s Macbeth 499

Personalized Teaching Experience

Personalize and tailor your teaching experience to the needs of your humanities course with Create, Insight, and instructor resources.

Create What You’ve Only Imagined

No two humanities courses are the same. That is why Gloria Fiero has personally hand-picked additional readings that can be added easily to a customized edition of The Humanistic Tradition. Marginal icons (right) that appear throughout this new edition indicate additional readings, a list of which is found at the end of the Table of Contents.

To customize your book using McGraw-Hill Create™, follow these steps:

1. Go to http://create.mheducation.com and sign in or register for an instructor account.

2. Click Collections (top, right) and select the “Traditions: Humanities Readings Through the Ages” Collection to preview and select readings. YoucanalsomakeuseofMcGraw-Hill’scomprehensive,cross-disciplinary content as well as other third-party resources.

3. Choose the readings that are most relevant to your students, your curriculum, and your own areas of interest.

4. Arrange the content in a way that makes the most sense for your course.

5. Personalize your book with your course information and choose the best format for your students—color, black-and-white, or ebook. When you are done, you will receive a free PDF review copy in just minutes.

Or contact your McGraw-Hill Education representative, who can help you build your unique version of The Humanisitic Tradition

Powerful Reporting on the Go

The first and only analytics tool of its kind, Connect Insight is a series of visual data displays—each framed by an intuitive question—that provide at-a-glance information regarding how your class is doing.

• Intuitive You receive an instant, at-a-glance view of student performance matched with student activity.

• Dynamic Connect Insight puts real-time analytics in your hands so you can take action early and keep struggling students from falling behind.

• Mobile Connect Insight travels from office to classroom, available on demand wherever and whenever it’s needed.

Instructor Resources

Connect Image Bank is an instructor database of images from select McGraw-Hill Education art and humanities titles, including The Humanistic Tradition. It includes all images for which McGraw-Hill has secured electronic permissions. With Connect Image Bank, instructors can access a text’s images by browsing its chapters, style/period, medium, and culture, or by searching with key terms. Images can be easily downloaded for use in presentations and in PowerPoints. The download includes a text file with image captions and information. You can access Connect Image Bank on the library tab in Connect Humanities (http://connect.mheducation.com). Various instructor resources are available for The Humanistic Tradition These include an instructor’s manual with discussion suggestions and study questions, music listening guides, lecture PowerPoints, and a test bank. Contact your McGraw-Hill sales representative for access to these materials.

BEFORE WE BEGIN

Studying humanities engages us in a dialogue with primary sources: works original to the age in which they were produced. Whether literary, visual, or aural, a primary source is a text; the time, place, and circumstances in which it was created constitute

Text

The text of a primary source refers to its medium (that is, what it is made of), its form (its outward shape), and its content (the subject it describes).

Literature: Literary form varies according to the manner in which words are arranged. So, poetry, which shares rhythmic organization with music and dance, is distinguished from prose, which normally lacks regular rhythmic patterns. Poetry, by its freedom from conventional grammar, provides unique opportunities for the expression of intense emotions. Prose usually functions to convey information, to narrate, and to describe.

Philosophy (the search for truth through reasoned analysis) and history (the record of the past) make use of prose to analyze and communicate ideas and information.

In literature, as in most forms of expression, content and form are usually interrelated. The subject matter or form of a literary work determines its genre. For instance, a long narrative poem recounting the adventures of a hero constitutes an epic, while a formal, dignified speech in praise of a person or thing constitutes a eulogy

The Visual Arts: The visual arts employ a wide variety of media, ranging from the traditional colored pigments used in painting, to wood, clay, marble, and (more recently) plastic and neon used in sculpture, to a wide variety of digital media, including photography and film. The form or outward shape of a work of art depends on the manner in which the artist manipulates the elements of color, line, texture, and space. Unlike words, these formal elements lack denotative meaning.

The visual arts are dominantly spatial, that is, they operate and are apprehended in space. Artists manipulate form to describe or interpret the visible world (as in the genres of portraiture and landscape), or to create worlds of fantasy and imagination. They may also fabricate texts that are nonrepresentational, that is, without identifiable subject matter.

Music and Dance: The medium of music is sound. Like literature, music is durational: it unfolds over the period of time in which it occurs. The major elements of music are melody, rhythm, harmony, and tone color—formal elements that also characterize the oral life of literature. However, while literary and visual texts are usually descriptive, music is almost always nonrepresentational: it rarely has meaning beyond sound itself. For that reason, music is the most difficult of the arts to describe in words. Dance, the artform that makes the human body itself the medium of expression, resembles music in that it is temporal and performance-oriented. Like music, dance

the context; and its various underlying meanings provide the subtext. Studying humanities from the perspective of text, context, and subtext helps us understand our cultural legacy and our place in the larger world.

exploits rhythm as a formal tool, and like painting and sculpture, it unfolds in space as well as in time.

Studying the text, we discover the ways in which the artist manipulates medium and form to achieve a characteristic manner of execution or expression that we call style. Comparing the styles of various texts from a single era, we discoverthattheyusuallysharecertaindefiningfeaturesand characteristics. Similarities between, for instance, ancient Greek temples and Greek tragedies, or between Chinese lyric poems and landscape paintings, reveal the unifying moral and aesthetic values of their respective cultures.

Context

The context describes the historical and cultural environment of a text. Understanding the relationship between text and context is one of the principal concerns of any inquiry into the humanistic tradition. To determine the context, we ask: In what time and place did our primary source originate? How did it function within the society in which it was created? Was it primarily decorative, didactic, magical, or propagandistic? Did it serve the religious or political needs of the community? Sometimes our answers to these questions are mere guesses. For instance, the paintings on the walls of Paleolithic caves were probably not “artworks” in the modern sense of the term, but, rather, magical signs associated with religious rituals performed in the interest of communal survival.

Determining the function of the text often serves to clarify the nature of its form, and vice-versa. For instance, in that the Hebrew Bible, the Song of Roland, and many other early literary works were spoken or sung, rather than read, such literature tends to feature repetition and rhyme, devices that facilitate memorization and oral delivery.

Subtext

The subtext of a primary source refers to its secondary or implied meanings. The subtext discloses conceptual messages embedded in or implied by the text. The epic poems of the ancient Greeks, for instance, which glorify prowess and physical courage, suggest an exclusively male perception of virtue. The state portraits of the seventeenth-century French king Louis XIV bear the subtext of unassailable and absolute power. In our own time, Andy Warhol’s serial adaptations of Coca-Cola bottles offer wry commentary on the commercial mentality of American society. Examining the implicit message of the text helps us determine the values of the age in which it was produced, and offers insights into our own.

The First Civilizations and the Classical Legacy

BOOK 1

The First Civilizations and the Classical Legacy

Introduction: Prehistory and the Birth of Civilization 1

1 Mesopotamia: Gods, Rulers, and the Social Order 17

2 Africa: Gods, Rulers, and the Social Order 44

3 India, China, and the Americas 63

4 Greece: Humanism and the Speculative Leap 76

5 The Classical Style 113

6 Rome: The Rise to Empire 137

7 China: The Rise to Empire 167

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

that money would thus be retained within the country. Within a very few months, he had erected a work near Leith for this manufacture, and brought home from Holland and Flanders ‘expert masters’ for making the cards, and ‘carvers for making the patterns,’ all of whom he took bound to instruct native workmen. In a very short time, we find him at war with two merchants who were accustomed to import playing-cards, and not disposed to brook his monopoly. Perhaps Peter was too vehement in his proceedings for the Scotch people among whom he cast his lot; perhaps they were unduly jealous of this keen-witted stranger. How it came we cannot tell; but before the work had been long erected, the tacksman of Canonmills set upon it and did somewhat to demolish it, and, horrid to relate, threw Madame de Bruis into the dam, besides using opprobrious words; for which he was fined in £50, and imprisoned. Not long after, Peter gained a triumph over the two importers of cards, for they were ordered by the Council to compound with him at so much a pack before they could be allowed to sell them.286

In the ensuing February, Peter was again in trouble. Alexander Daes, owner of the papermanufactory at Dalry Mills, complained that his privilege of making paper and playing-cards had been infringed by Peter Bruce and James Lithgow, who had clandestinely obtained a licence for a playing-card manufactory. They had likewise enticed away a workman named Nicolas de Champ, whom he had brought from France, and caused the abstraction from his work of some of his haircloths. The Council freed Peter and his associate from everything but the charge of taking away the haircloths, which they left to be dealt with by the ordinary judge.—P.C.R.

1682. FEB. 16. 1681.

Altogether, Peter seems to have found great difficulty in preventing a sale of foreign cards. It was difficult to detect the importation of such articles. A package containing a quantity of them had lately been brought by the ship of one Adam Watt; and even the custom-house officer winked at its being smuggled ashore. Peter craved the

Council (June 7, 1682) for general letters against the contraveners of his privilege; but the Council, apparently warned by the complaints about the Messrs Fountain, would only, on that occasion, agree to give warrant for particular cases. Afterwards (July 5), they gave a more general warrant, but still declaring that Bruce, in the event of making a wrong charge, should be liable to a fine.

Finally, persecuted out of Edinburgh, Peter betook himself to Glasgow, and tried to set up a paper-mill at Woodside, near that city; but here, too, he encountered a variety of troubles and oppressions, designed for the purpose of neutralising his monopoly of the manufacture of playing-cards, his builders failing in their engagements, his men being seduced away from him, his mill-course defrauded of water, and so forth. He complained to the Privy Council (January 6, 1685), and got a decree against his two chief persecutors, John Campbell and James Peddie, for a thousand merks as compensation for the injuries he had suffered. When everything else failed, Peter seems to have turned his religious professions to some account, as he is last seen acting as printer to the Catholic chapel and college at Holyrood—where, doubtless, the Revolution gave him a disagreeable surprise.

DEC. 26.

The college youths renewed the demonstration of last year. ‘Their preparations were so quiet, that none suspected it this year. They brought [the pope] to the Cross, and fixed his chair in that place where the gallows stands. He was tricked up in a red gown and a mitre, with two keys over his arm, a crucifix in one hand, and the oath of the Test in the other. Then they put fire to him, and it burnt lengthy till it came to the powder, at which he blew up in the air.

‘At this time, many things were done in mockery of the Test: one I shall tell. The children of Heriot’s Hospital, finding that the dog which kept the yards of that hospital had a public charge and office,

ordained him to take the Test, and offered him a paper. But he, loving a bone better than it, absolutely refused it. They then rubbed it over with butter, which they called an Explication of the Test, in imitation of Argyle, and he licked off the butter, but did spit out the paper; for which they held a jury upon him, and, in derision of the sentence on Argyle, they found the dog guilty of treason, and actually hanged him.’—Foun.

Alexander Cockburn, the hangman of Edinburgh, was tried before the magistrates as sheriffs, for the murder, in his own house, of one Adamson or Mackenzie, a blue-gown beggar. The proof was slender, and chiefly of the nature of presumption— as, that he had denied Adamson’s being in his house on the alleged day, the contrary being proved, groans having been heard, and bloody clothes found in the house; and this evidence, too, was chiefly from women. Yet he was condemned to be hanged within three suns. One Mackenzie, whom Cockburn had caused to lose his place of hangman at Stirling, performed the office.—Foun.

1682. JAN. 16. 1682.

EB. 11.

Three men were drowned this day, by falling through the ice on the North Loch. ‘We have a proverb that the fox will not set his foot on the ice after Candlemas, especially in the heat of the sun, as this was at two o’clock; and at any time the fox is so sagacious as to lay his ear to the ice, to see if it be frozen to the bottom, or if he hear the murmuring and current of the water.’—Foun.

A strange story was circulated regarding a servant lass in the burgh of Irvine. Her mistress, the wife of the Honourable Major Montgomery, having had some silver articles stolen, blamed the lass, who, taking the accusation much amiss, and protesting her innocence, said she would learn who took those things, though she should raise the devil for it. The master and mistress let this pass as a rash speech; but the girl, being resolute, on a certain day ‘goes down to a laigh cellar, takes a Bible with her, and draws a circle about her, and turns a riddle on end twice from south to north, or from the right hand to the left hand, having in her hand nine feathers, which she pulled out of the tail of a black cock, and having read the 21st [psalm] forward, she reads backward chap. ix., verse 19, of the book of Revelation; he appears in a seaman’s clothing, with a blue cap, and asks what she would. She puts one question to him, and he answers it; and she casts three of the feathers at him, charging him to his place again; then he disappears. He seemed to her to rise out of the earth to the middle of his body. She reads the same verse backward the second time, and he appears the second time, rising out of the ground, with one leg above the ground; she asks him a second question, and she casts other three feathers at him, charging him to his place; he again disappears. She reads again the third time the verse backward, and he appears the third time with his body above ground (the last two times in the shape of a black grim man in black clothing, and the last time with a long tail); she asks a third question at him, and casts the three last feathers at him, charging him to his place; and he disappears. The majorgeneral and his lady, being above stairs, though not knowing what was a-working, were sore afraid, and could give no reason of it; the dogs in the city making a hideous barking round about. This done, the woman, aghast, and pale as death, comes and tells her lady who had stolen the things she missed, and they were in such a chest in her house, belonging to some of the servants; which being searched, was found accordingly. Some of the servants, suspecting her to be about this work, tells the major of it, and tells him they saw her go down to the cellar; he lays her up in prison, and she

FEB. 1682.

confesses as is before related, telling them that she learned it in Dr Colvin’s house in Ireland, who used to practise this.’—Law.

Fountainhall relates this story more briefly as ‘a strange accident,’ and remarks that the divination per cribrum (by the sieve) is very ancient, having been practised among the Greeks. He is puzzled about her confession, as it may be from frenzy and hatred of life; but if the fact of the consultation can be proved, he is clear that it infers death.

Divination by a sieve was performed in this manner: ‘The sieve being suspended, after repeating a certain form of words, it is taken between the two fingers only, and the names of the parties suspected, repeated: he at whose name the sieve turns, trembles, or shakes, is reputed guilty of the evil in question.... It was sometimes practised by suspending the sieve by a thread, or fixing it to the points of a pair of scissors, giving it room to turn, and naming as before the parties suspected: in this manner Coscinomancy is still practised in some parts of England.’—Demonologia. By J. S. F . London, 1827; p. 146.

‘Strange apparitions were seen in and about Glasgow, and strange voices and wild cries [were heard], particularly one night about the Deanside well, was heard a cry, Help, help!‘—Law. Many such occurrences are noted about this time and for four or five years before. In March 1679, for instance, a voice was heard at Paisley Abbey, crying: ‘Wo, wo, wo—pray, pray, pray!’ Such reports reveal the excited state of the public mind and a general sense of anxiety under the religious variances of the time.

FEB. 1682. MAR.

Major Learmont, an old soldier of the Covenant, though only a tailor to his trade, was taken in his own house near Lanark, or rather in a vault connected with it which he had contrived for hiding. ‘It had its entry

in his house, upon the side of a wall, and closed up with a whole stone, so close that none could have judged it but to be a stone of the building. It descended below the foundation of the house, and was in length about forty yards, and in the far end, the other mouth of it, was closed with feal [turf], having a feal dyke built upon it; so that with ease, when he went out, he shot out the feal and closed it again. Here he sheltered for the space of sixteen years, taking to it at every alarm, and many times hath his house been searched for him by the soldiers; but where he sheltered none was privy to it but his own domestics, and at length it is discovered by his own herdsman.’—Law.

MAR. 9.

Thomas Barclay of Collerine in Fife was a youth of eighteen, in possession of ‘an opulent estate,’ and likewise of a considerable jurisdiction in his county. His predecessors were loyalists; but Thomas himself, by the remarriage of his mother to Mure of Rowallan in Ayrshire, was, according to the allegation of his uncle John Barclay, in the way of being ‘bred up in a family of fanatical and disloyal principles, not being permitted to visit or be acquainted with his nearest relations and friends, and denied all manner of education suitable to his quality ... not being sent to college’—he had, moreover, been influenced to choose ‘curators altogether strangers to his family, of known disaffected and disloyal principles.’ It seemed, in John Barclay’s judgment, unavoidable in these circumstances that a supporter would be lost to his majesty’s interests, unless a remedy were provided.

It seems so far creditable to a government which has a good many sins at its charge, that, when this case came before the Duke of York and the Privy Council, on John Barclay’s petition, and both sides had been heard—namely, the uncle on one side, and the Lady Rowallan, with the three curators, Montgomery younger of Skelmorley, the Laird of Dunlop, and Mr John Stirling, minister of Irvine, on the other

—they decided that the young Barclay was of age to act and choose curators for himself, and that the defenders were not bound to produce him in court; thus frankly consenting that the young man should rest in the danger of being perverted from the loyalty of his family.— P.C.R.

A severe murrain commenced amongst the cattle, thought to be owing to the deficient herbage of the preceding year, and the heavy rains of the intermediate season.287 The support of cattle during winter was at all times a trying difficulty in those days of no turnip-husbandry; but on an occasion like this it was scarcely possible. It was remarked that the farmers had to cut heather for their beasts to lie upon, and pull the old straw out of the coverings of their houses to feed them with. The murrain lasted till May, when some tenants in the Highlands lost as many as forty cows by it.

1682. APR.

PR. 18.

A complaint presented to the Privy Council by Janet Stewart, servant to Mr William Dundas, advocate, set forth that James Aikenhead, apothecary in Edinburgh, took upon him ‘to compose and vent poisonous tablets,’ and ‘Mistress Elizabeth Edmonstoun, having got notice of these tablets, and that they would work strange wanton affections and humours in the bodies of women,’ sent James Chalmers for some of them, which she caused to be administered to the complainer, in presence of several persons, ‘as a sweetmeat tablet.’ Janet having innocently accepted of the tablet, ate of it, and in consequence ‘fell into a great fever, wherein she continued for twenty days, before anybody knew what was the cause of it; so that the poison has crept into her bones, and she is like never to recover.’

Fountainhall tells us that Janet would not have recovered, ‘had not Doctor Irvine given her an antidote.’ The Council remitted the case to the College of Physicians, as being skilled in such matters (periti

in arte), ‘who,’ says Fountainhall, ‘thought such medicaments not safe to be given withoutfirsttakingtheirownadvice.’288

MAY 3. 1682.

A riot took place in the streets of Edinburgh, in consequence of an attempt to carry away, as soldiers to serve the Prince of Orange, some young men who had been imprisoned for a trivial offence. As the lads were marched down the street under a guard, to be put on board a ship in Leith Road, some women called out to them: ‘Pressed or not pressed?’ They answered: ‘Pressed,’ and so caused an excitement in the multitude. A woman who sat on the street selling pottery, threw a few sherds at the guard, and some other people, finding a supply of missiles at a house which was building, followed her example. ‘The king’s forces,’ says Fountainhall, ‘were exceedingly assaulted and abused.’ Under the order of their commander, Major Keith, they turned and fired upon the crowd, when, as usual, only innocent bystanders were injured. Seven men and two women were killed, and twenty-five wounded—a greater bloodshed than ‘has been at once these sixty years done in the streets of Edinburgh.’ One of the women being pregnant, the child was cut from her and baptised in the streets. Three of the most active individuals in this mob were seized and tried, but the assize would not find them guilty. The magistrates were severely blamed for their negligence and cowardice in this affair.

It gave origin to the well-known Town-guardof Edinburgh, for, under the recommendation of the Privy Council, and with the sanction of the king, it was agreed to raise a body of a hundred and eight men, to serve as a protection to the city in all emergencies. The inhabitants were taxed to pay for it, ‘some a groat, some fivepence, and the highest at sixpence a week;’ but this being found oppressive, the support of the corps, which cost 22,000 merks a year, was soon after put upon the town’s common good.289 Patrick

Graham, a younger son of Graham of Inchbrakie, was appointed captain, at the dictation of the Duke of York, who, says Fountainhall, ‘would give a vast sum to have such a breach in London’s walls.’

Many who remember the Town-guard, with their rusty brown uniform, their Lochaber axes, and fierce Highland faces, as a curiosity of the streets of Edinburgh in their young days, will be perhaps unpleasingly surprised to learn that the corps was originally an engine of the government of the last Stuarts. Captain Graham, who was a sincere loyalist by blood, being descended from the Inchbrakie who sheltered Montrose on his commencing the insurrection of 1644, figured with his guards on various occasions during the remainder of the Stuart reigns, particularly at the bringing in of the Earl of Argyle to be executed in 1685, when he and the hangman received the unhappy Maccallummore at the Watergate, and conducted him along the street to prison.

The Town-guard was disbanded in November 1817, by which time it had been reduced to twenty-five privates, two sergeants, two corporals, and two drummers.

1682.

The Gloucesterfrigate, on her voyage from London to Edinburgh with the Duke of York and his friends, and attended by some smaller vessels, was by a blunder wrecked on Yarmouth Sands. A signal-gun brought boats from the other vessels to the rescue of the distressed party, and the duke and several other men of importance were taken from the vessel, just before she went to pieces. A hundred and fifty persons, of whom eighty were men of quality, including the Earl of Roxburgh, the Laird of Hopetoun, Sir Joseph Douglas of Pumpherston, and Lord O’Brian of the Irish peerage, were drowned. Sir George Gordon of Haddo, president of the Court of Session, and who had just received the high appointment of Chancellor of Scotland, escaped by leaping

into the water, whence he was drawn by the hair of the head into a boat. The Earl of Roxburgh had been heard crying for a boat, and offering twenty thousand guineas for one. His servant in the water took him on his back, and was swimming with him to a boat, when a drowning person clutched at them, and the unfortunate earl fell off and perished, his servant barely escaping for the moment, and dying an hour after. The duke and the rest of the survivors arrived in Leith next day, without further accident.

‘The pilot, one Aird, of Borrowstounness, was threatened with hanging for going to sleep and giving wrong directions ... he was condemned to perpetual imprisonment.’—Foun.

It is remarkable that the widow of the Earl of Roxburgh survived him inwidowhoodfor seventy-one years, dying in 1753.

JUNE 13. 1682.

Sir Alexander Lindsay of Evelick—an ancient castle on the high grounds overlooking the Carse of Gowrie—had married as a second wife the widow of Mr William Douglas, ‘the advocate and poet.’290 Both had children approaching maturity, and William Douglas, the lady’s son, became very naturally the playfellow of Sir Alexander’s heir Thomas. Whether jealousy on account of the superior prospects of Thomas Lindsay had entered William Douglas’s heart, we cannot tell; but the two boys being out one day in the Den of Pitrodie, a romantic broomy dell near Evelick, Douglas was tempted to stab Lindsay with a clasp-knife, and so murder him.

The wretched boy gave a confession next day, fully admitting his guilt. It commences thus: ‘I have been over proud and rash all my life. I was never yet firmly convinced there was a God or a devil, a heaven or a hell, till now. To tell the way how I did the deed my heart doth quake [and] head ryves. As I was playing and kittling at the head of the brae, I stabbed him with the only knife which I have, and I tumbled down the brae with him to the burn; all the way he

was struggling with me, while I fell upon him in the burn, and there he uttered one or two pitiful words. The Lord Omnipotent and allseeing God learn my heart to repent.’ On this occasion, ‘he also produced the little knife called Jocktheleig, with ane iron haft.’

Being on the ensuing day brought before the sheriff-court of Perth, it was there alleged against him that ‘he did conceive ane deadly hatred and evil [will] against Thomas Lindsay, son to Sir Alexander Lindsay of Evelick, with a settled resolution to bereave him of life; he did upon the thretteen day of this instant month, being Tuesday last, about seven hours in the afternoon or thereby, as he was coming along the Den of Pitrodie in company with the said Thomas Lindsay, fall upon the said Thomas, and with his knife did give him five several stabs and wounds in his body, whereof one about the mouth of his stomach, and thereafter dragged him down the brae of the den to the burn, and there with his feet did trample upon the said Thomas lying in the water, and as yet he not being satisfied with all that cruelty which he did to the said Thomas, he did with a stone dash him upon the head, so that immediately the said Thomas died.’

To the great concern of his friends, the boy now retracted his confession, alleging that he found Thomas Lindsay lying in the burn, and in trying to help him up had fallen upon him. The trial was consequently postponed to a future day. Meanwhile his friends exerted themselves to bring back the culprit to a sense of his guilt, and after a few days, they seem to have succeeded. On the 25th of June, his mother is found writing to the Laird of Balhaivie, a cousin of the murdered youth, relating how she had been witness to the power of God in changing the heart of the obstinate. ‘In a very little,’ says she, ‘after you went to the door, he rose up in such a passion of grief and sorrow, crying out in such bitterness, rapping on the table, and cursing the hour it entered into his head to recant, and promised through the Lord’s strength, nothing should persuade him to do it again, but that he should constantly affirm the truth of his first declaration. He took out the declaration the devil had belied him to write, and cried to cast it in the fire, with so much sorrow and tears,

1682.

as he took his head in his hand and said he feared to distract [become distracted], and prayed that the Lord would help him in his right judgment, that he might still adhere to truth. This,’ continues the wretched mother, ‘was some consolation to my poor confounded mind; but when I consider that deceitful bow the heart, and his frequent distemper, my spirit fails.... I desire you and the rest of your worthy friends no to pit yourself to needless charges in the affair, for I, his nearest relation, being not only convinced justice should be satisfied, but am desirous nothing may occur to hinder. And as I know, though both he and I hath creditable friends, they will be ashamed to own me in this. The good God that best knows my pitiful case bear [me] up under this dismal lot, and give you and all Christians a heart to pray for him, and your poor afflicked servant, Rachel Kirkwood.’

The Laird of Balhaivie seems to have entered kindly into the lady’s feelings. His answer contains a few traits highly characteristic of the time. ‘Much honoured madam, as soon as Sir Pat[rick Threipland] gave me account yesternight of your son’s second confession, I went alongs with Sir Patrick and saw him, and I swear to outward appearance he seemed very serious, and I pray God Almighty continue him so.... My cousin, young Evelick, and all his relations are very sensible of your ladyship’s extraordinary and wonderful good carriage in ane affair so astounding as this has been, and ye renew it in your letter, wherein ye desire they should not be put to needless trouble and charges in the affair. The truth is, madam, there is none of us but are grieved to the bottom of our hearts that we should be obliged to pursue your son to death; but we keep evil consciences if we suffer the murder of so near a relation to go unpunished; and his life for the taking away of the other’s is the least atonement that credit and conscience can allow.... His dying by the hand of justice will be the only way to expiate so great a crime, and likewise be a means to take away all occasion of grudge which otherwise could not but continue in the family....’291

1682.

The youth was brought to trial in Edinburgh, and condemned to suffer death on the 4th of August. After the trial, he confessed that it was he who in the January preceding ‘put fire in Henry Graham’s writing-chamber, out of revenge, and that he had first stolen some books there.’ He was subjected to a new trial for this crime, because, being treason, it would have inferred a forfeiture of his estate, worth upwards of £2000; but on this occasion he retracted his confession, nor could any thing prevail with him to renew it judicially. The jury, who were honest Edinburgh citizens, seeing that the design was to enrich certain courtiers at the expense of the sisters of the young homicide, acquitted him of the new charge, to the great irritation of the king’s advocate, who ‘swore that the next assizers he should choose should be Linlithgow’s soldiers, to curb the phanaticks.’292

The magistrates of Dumfries had a man called Richard Storie in their jail, on a charge of murder, and were put to great charges in keeping and guarding him, because several of his friends from the Borders daily threatenedtoforcetheprisonand permit him to make his escape ‘if he shall remain any longer there.’293 It was therefore found necessary to order that Storie should be transferred by the sheriff under a sufficient guard to the next sheriff upon the road to Edinburgh, and so on to Edinburgh itself, where he should be placed in firmance in the Tolbooth.

JULY 5. 1682.

There was the more reason for the magistrates of Dumfries being anxious about the detention of Richard Storie, that George Storie, an associate in his crime, had already escaped. These two men were accused of having basely and cruelly murdered Francis Armstrong in Alisonbank, in the preceding month of June. The witnesses being Englishmen, it was necessary (December 7, 1682) to recommend to the sheriff of

Cumberland to take measures for insuring their appearance before the Court of Justiciary at the approaching trial. This proving ineffectual, the widow and six children of Francis Armstrong petitioned in March for further and more effectual efforts; and the lords agreed to address the English secretary of state on the subject. Not long after (April 30, 1684), the Council was informed that, ‘by the throng of prisoners in the Tolbooth of Dumfries, the same has been already broken, and is yet in the same hazard.’ Being at the same time made aware ‘that, within the castle of Dumfries, there are some strong vaults fit for the keeping of prisoners,’ they gave orders to have these prepared for the

JULY 7.

A poor Quaker, named Thomas Dunlop, had taken a house in Musselburgh, and was endeavouring by humble industry to support himself and his family, without being burdensome to any. But other Quakers came occasionally about him, to the annoyance of the magistrates of the town; and finding he broke a local law, in having no certificate of character from the minister of the parish in which he had last resided, they took advantage of the circumstance to get quit of him. Poor Thomas and his wife and little children were thrust out of their home into the fields, notwithstanding his entreaties for delay till he should get letters certifying his respectability from persons they knew. He had now been lodging for thirteen days and nights in the fields, the magistrates resisting all pleadings in his favour from charitable persons, and disregarding the misery which he was manifestly enduring. On his petition to that body which almost every week was sending recusant Whigs to the scaffold, they lent him a patient hearing, and summoned the Musselburgh magistrates before them; but all that the laws permitted them to do in the case, was to ordain that Thomas might have recourse to a legal action if the magistrates had not ‘removed him in ane orderly manner.’—P.C.R.

James Somerville, younger of Drum, riding home to that place from Edinburgh, found on the way two friends fighting with swords—namely, Thomas Learmont, son of Mr Thomas Learmont, an advocate, and Hew Paterson, younger of Bannockburn. These two young men had quarrelled over their cups. Young Somerville dismounted, and tried to separate them, but received a mortal wound from Paterson’s sword, though inflicted by the hand of Learmont, the two combatants having perhaps, like Hamlet and Laertes, exchanged weapons. The wounded man lived two days, and expressed his forgiveness of Learmont, who, by his advice, fled. ‘Some alleged his wounds were not mortal, but misguided.’ Somerville was the progeny of the marriage described as having taken place at Corehouse in November 1650. He left an infant son, who carried on the line of the family.—Foun.

JULY 8. 1682.

A comet began to appear in the north-west. ‘The star was big, and the tail broad and long, at the appearance of four yards.’ It continued visible for twenty days. Law.

AUG. 17.

This was the celebrated Halley’s Comet, so called in honour of the illustrious astronomer who first ascertained, by his calculations regarding it, the periodicity of comets. The same object had been observed by Kepler in 1607, and by Apian in 1531. ‘The identity of these meteors seeming to Halley unquestionable, he ventured to predict that the same comet would reappear in 1758, and that it would be found to revolve in a very elongated ellipse in about seventy-six years. As the critical period approached, which was to decide so momentous a question regarding the system of the world, the greatest mathematicians endeavoured to track the comet’s course with a minuteness which Halley’s opportunities did not permit

him to reach. The illustrious Clairhaut, feeling that a general prediction was not enough, undertook the most complex problem as to the disturbing effects of the planets through whose orbits it must pass.... He succeeded in predicting one of the positions for the comet for the middle of April; stating, however, that he might be in error by thirty days. The comet occupied the position referred to on the 12th of March.’—Nichol’sContemplationsontheSolarSystem.

It is humiliating to have to remark, that the notices of comets which we derive from Scotch writers down to this time, contain nothing but accounts of the popular fancies regarding them. Practical astronomy seems to have then been unknown in our country; and hence, while in other lands men were carefully observing, computing, and approaching to just conclusions regarding these illustrious strangers of the sky, our diarists could only tell us how many yards long they seemed to be, what effects were apprehended from them in the way of war and pestilence, and how certain pious divines ‘improved’ them for spiritual edification. Early in this century, Scotland had produced one great philosopher—who had supplied his craft with the mathematical instrument by which complex problems, such as the movement of comets, were alone to be solved. It might have been expected that the country of Napier, seventy years after his time, would have had many sons capable of applying his key to such mysteries of nature. But not one had arisen—nor did any rise for fifty years onward, when at length Colin Maclaurin unfolded in the Edinburgh University the sublime philosophy of Newton. There could not be a more expressive signification of the character of the seventeenth century in Scotland. Our unhappy contentions about external religious matters had absorbed the whole genius of the people, rendering to us the age of Cowley, of Waller, and of Milton, as barren of elegant literature, as that of Horrocks, of Halley, and of Newton, was of science.

1682.

NOV. 23.

John Corse, Andrew Armour, and Robert Burne, merchants in Glasgow, were now arranging for the setting up of a manufactory ‘for making of damaties, fustines, and stripped vermiliones,’ expecting it would be ‘a great advantage to the country, and keep in much money therein which is sent out thereof for import of the same.’ Seeing ‘it undoubtedly will require a great stock and many servants, strangers, which are come and are to be sent for,’ the enterprisers deemed themselves entitled to have their work declared a manufactory, so that it might enjoy the privileges accorded to such by act of parliament. This favour was granted by the Council for nine years, ‘but prejudice to any other persons to set up and work in the said work.’—P.C.R.

Daniel Mure of Gledstanes,294 out of health and mental vigour, and believed to be on his deathbed, was induced to make a disposition of his estate to Thomas Carmichael of Eastend. Such a disposition, however, could not be valid by the law of Scotland, unless the testator appeared afterwards ‘at kirk and market’—an arrangement designed to insure that natural heirs should not be cheated. By ‘a most devilish contrivance’ of William Chiesley, writer in Edinburgh, Thomas Bell, Carmichael’s servant, was dressed up to personate the sick man, and taken with all due form to the public places appointed by the law. The notary before whom the man presented himself was so doubtful of his being Daniel Mure, that he caused him to take his oath that he was truly that person. When Carmichael and his man afterwards retired to a tavern with the notary, the latter once more expressed his doubt, saying: ‘This person is certainly not like Daniel Mure;’ to which Carmichael answered, that he was really the man, but much altered by sickness. On the death of Daniel Mure soon after, Carmichael accordingly appeared as the inheritor of the estate of Gledstanes, to

DEC. 1682.

the exclusion of Francis Mure, merchant in Edinburgh, the brother of the deceased. The affair was the more wicked, as the estate was one which had been long in Mure’s family.

On the whole matter being brought before the Privy Council by Francis Mure, the truth became clear, and Carmichael was punished by a fine of five thousand merks, whereof two thousand were assigned to Francis, as a compensation for the damage he had sustained; while Chiesley, the writer, was mulcted in three thousand merks for being accessory to the cheat. An obligation which Francis Mure had been induced to give to Carmichael, binding himself never to expose or pursue the forgery, was at the same time discharged. It is not unworthy of remark, that Chiesley, who had devised this forgery and drawn up the iniquitous obligation aforesaid, was one of those members of the legal profession who had refused, from scruples of conscience, to take the Test. P.C.R.

DEC. 21.

DEC. 23.

Alexander Nisbet of Craigentinny and Macdougall of Makerston had gone abroad to fight a duel, attended by Sir William Scott of Harden and Douglas, ‘ensign to Colonel Douglas,’ as seconds. The Privy Council hearing of it, ordered the four gentlemen to be confined in the Tolbooth in different rooms, until it should be inquired into. The principals were, on petition, set at liberty in a few days, after giving caution for reappearance.—P.C.R.

1683. JAN. 5.

The widow of Andrew Anderson at this time carried on business in Edinburgh as the king’s printer, by virtue of a royal gift debarring others from exercising the like art. The bibles produced by her are said by

1683.

Fountainhall to have been wretchedly executed. One David Lindsay having now got a similar gift, Mrs Anderson endeavoured to keep him out of the trade, setting forth that she had been previously invested with the privilege, and ‘onepressissufficientlyabletoserveallScotland, our printing being but inconsiderable.’295 The Lords ordained that Mrs Anderson’s monopoly should be held as only including the printing of such things as had been specified in the gift to her husband’s predecessor Tyler.

There were at this time printers in Glasgow and Aberdeen, but probably no other part of Scotland—though St Andrews had had a press before the Reformation. The business of the printer has been of slow growth in our country. Edinburgh contained in 1763 only six printing-offices; in 1790, sixteen;296 there are, in 1858, sixty-two printing firms, besides several publishing offices, in which special printing work is executed.

It was represented to the Privy Council by the Bishop of Aberdeen that the Quakers in his diocese were now proceeding to such insolency, as to erect meeting-houses for their worship and ‘schools for training up their children in their godless and heretical opinions;’ providing funds for the support of these establishments, and in some instances adding burial-grounds for their own special use. The Council issued orders to have proper investigations made amongst the leading Quakers concerned and the proprietors of the ground on which the said meeting-houses and schools had been built.—P.C.R.

At the funeral of the Duke of Lauderdale at Haddington, while the usual dole of money was distributing among the beggars, one,

named Bell, stabbed another. ‘He was apprehended, and several stolen things found on him; and, he being made to touch the corpse, the wound bled afresh. The town of Haddington, who it seems have a sheriff’s power, judged him presently, and hanged him over the bridge next day.’—Foun.

APR. 5. APR. 19. 1683.

Alexander Robertson of Struan, whom we saw two years back breaking out with mortal fury against an agent of the Marquis of Athole in the chamber of the Privy Council, now comes before us in a more agreeable light—namely, as one seeking to cultivate an industrial economy in the midst of the vicious idleness and barbarism of the Highlands. Far up among the Perthshire alps, on the dreary shores of Loch Rannoch, there was then ‘a considerable wood,’ the property of Struan. This would have been useless to him and the country—being in so remote a wilderness—‘if he had not, with great expenses and trouble, caused erect saw-mills, in which, these divers years past, there has been made the number of 176,000 deals.’ This had redounded ‘to the great benefit and conveniency of the country adjacent, besides the keeping of many persons at work’ who would otherwise have been idle and in wretchedness. Struan, however, could not obtain a market for the great bulk of his timber, without sending it in floats along Loch Rannoch, and down the water of Tummel into the Tay; and in this long and tedious passage, it was sometimes driven by storms and spates [floods] on shore, or on the banks of the rivers, where it was made prey of by the country people, ‘thinking they would be no further liable than to a deadspulyie.’ Occasionally, ‘louss and broken men’ attacked his mills in the night-time, and helped themselves to such timber as they wanted. ‘So that his work was likely to be broken and ruined.’ The Privy Council, on Struan’s petition, issued a strong edict for the prevention of these spoliations, and further gave

him power to make roads between his saw-mills in Carrie and Apnadull, and to take a charge of those from Rannoch to Perth, so that he might have the alternative of land-carriage for his timber.—P . C.R.

The chance of getting the spoliations put down must have been very small, for thieving raged like a very pestilence in the Highlands. The Earl of Perth, writing from Drummond in July 1682, says expressively: ‘We are so plagued with thieving here, it would pity any heart to see the condition the poor people are in.’297

Sir Thomas Stewart of Coltness298 was obliged to fly to Holland, in consequence of a vague threat held out by Sir George Mackenzie, supposed to have been designed to frighten the unfortunate gentleman away, that his estate might be seized. The subsequent circumstances, as related by his son, give a striking view of the troubles in which a Presbyterian family of rank might then be involved, even while making no active demonstrations against the government.

APR. 1683.

‘The day after he was gone, came one of the Lord Advocate’s emissaries, Irvine of Bonshaw, with a party of dragoons heated with fury and with liquor.... They demanded the family horses, though their warrant bore no more than to apprehend the person of Thomas Stewart of Coltness; and when Irvine was told by Mr James Stewart, Coltness’s second son, that he was acting beyond orders in offering to seize horses or goods, he swore and blasphemed against rebels and assassins, and that any treatment was warrantable against such. The child Robert made some childish noise, and he threw down the boy of eight years old from a high leaping-on stone. The lady, seven months gone with child, came down to reason with him, but he was so much the more enraged. He offered to shoot the groom [who] stood behind, for denying the keys of the stable, and at length

carried off the young gentlemen David and James’s horses.... There was a complaint given in at Edinburgh, and the horses were returned, jaded and abused by ramblers. This Mr Irvine, some months after, in a drunken quarrel at Lanark, was stabbed to death on a dunghill by one of his own gang: a proper exit for such a bloodhound.’

The lady immediately displenished her house, and, notwithstanding the delicate state in which she was, prepared to follow her husband to Holland. Taking with her her step-son David, and a niece of three years, the child of Mr James Stewart, also an exile in Holland, she set sail from Borrowstounness in the beginning of June. The ship encountered a severe storm. ‘The sea was so boisterous, the lady was in danger of being tossed from her bed, and her step-son was alarmed, and got up staggering in the hold, and bewailing; but she composedly said: “David, go to your cabin-bed, and be more quiet, for there is no back-door here to fly out by.” In some days after, they got safe to harbour. They took the treck-scuit from Rotterdam to Utrecht, and a surprising accident happened by the way, and in the scuit close by her: a Dutch minister’s wife, a fellow-traveller and with child, miscarried and died instantly. The husband was as one distracted, and would not be persuaded she was dead, but in a swoon. He made lamentable outcries, but all to no effect. This was alarming to the lady, and made her reflect and acknowledge the kind Providence had preserved her and the fruit of her womb, when in danger both in the journey and the stormy voyage. Coltness has a remark of thanksgiving on this in his diary, and concludes with this, “God makes our hymn sound both of mercy and judgment.”

‘Her husband, with Mr Pringle of Torwoodlee, came half-way on to Leyden, and met these recent fugitives, and conducted them to Utrecht, where trouble was in part forgot, and sorrow in some measure fled, upon the first transports of being safe and together. Here was the ingenuous, upright Archibald Earl of Argyle, too virtuous for so licentious a court as that of King Charles. Here was the Earl of Loudon, who died anno 1684, and lies buried in the English church

1683.

at Leyden. There was here the Lord Viscount Stair, and with him for education his son, Sir David Dalrymple, in better times Lord Advocate, and his grandson John, that great general under Queen Anne, and the ambassador of elegant figure in France, and a fieldmarshal under King George. Here was also Lord Melville, [who became] High Commissioner to the Restitution Parliament under King William, and secretary of state, and with him his son the Earl of Leven, who went to the king of Prussia’s service, and after this was commander-in-chief in Scotland, and governor of Edinburgh Castle in Queen Anne’s reign. But it were endless to name all the honest party of gentry and ministers, outlawed, banished, and forfaulted, for the cause of religion and civil liberty.’

In July, Lady Coltness brought into the world the person who relates the above particulars. ‘The occasion was joyful to the parents; but the mother had not the blessing of the breasts, and there was hard procuring a nurse for a stranger. This gave a damp; but a Dutch lady was so kind as wean her daughter a little sooner, and so a careful and experienced nurse was procured.’

‘... Coltness fell in straits ... for he soon spent the little he brought with him, and remittances were uncertain and but small. His friends at home were under a cloud. Alertoun, his brother-in-law, was imprisoned and fined; Sir John Maxwell, his other brother-in-law, was fined £10,000 and imprisoned; and his younger children had none to care for them, but their grandmother, Sir James Stewart’s widow. She had a large jointure [that] was not affected, and acted the part of a kind parent.... In this present situation, the old widow lady could give little relief to those banished. It was chargeable supporting the expenses of a family in Holland, and all visible sources were stopped or withdrawn; yet a kind Providence raised up friends in a strange land. Of these the most sympathising was Mr Andrew Russell, merchant-factor at Rotterdam; he generously proffered money, and genteelly, as it were, forced it upon Coltness (and so he did to Sir Patrick Hume of Polwarth, Mr James Stewart, advocate, and others),

1683.