The EARCOS Triannual JOURNAL

A Link to Educational Excellence in East Asia FALL 2025

Featured in this Issue

Leadership Leading Together for a Stronger Community: Board Chair–Head of School Partnership

Curriculum

A Spoonful of Sugar: Sweetening Science with the STEAM Approach in Biology

Green & Sustainable Sustainability as a Transformative Practice: Connecting Art and Environmental Awareness

THE EARCOS JOURNAL

The ET Journal is a triannual publication of the East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS), a nonprofit 501(C)3, incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA, with a regional office in Manila, Philippines. Membership in EARCOS is open to elementary and secondary schools in East Asia which offer an educational program using English as the primary language of instruction, and to other organizations, institutions, and individuals.

OBJECTIVES AND PURPOSES

* To promote intercultural understanding and international friendship through the activities of member schools.

* To broaden the dimensions of education of all schools involved in the Council in the interest of a total program of education.

* To advance the professional growth and welfare of individuals belonging to the educational staff of member schools.

* To facilitate communication and cooperative action between and among all associated schools.

* To cooperate with other organizations and individuals pursuing the same objectives as the Council.

EARCOS BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Catriona Moran (Saigon South International School), President

James Dalziel (NIST International School), Vice President

Jim Gerhard (Seoul International School), Secretary

Rami Madani (The International School of Kuala Lumpur), Treasurer

Gregory Hedger (The International School Yangon), WASC Representative

Karrie Dietz (Australian International School Singapore)

Matthew Parr (Nagoya International School)

Marta Medved Krajnovic (Western Academy of Beijing)

Maya Nelson (Jakarta Intercultural School)

Kevin Baker (American International School Guangzhou), Past President

Margaret Alvarez (WASC), Ex-Officio

Andrew Hoover (Office of Overseas Schools, REO, East Asia Pacific)

EARCOS STAFF

Edward E. Greene, Executive Director

Cameron Janzen, Deputy Director

Bill Oldread, Assistant Director Emeritus

Kristine De Castro, Assistant to the Executive Director

Maica Cruz, Events Coordinator

Porntip (Joom) Rattanapetch, Administrative Assistant & Membership Coordinator

Edzel Drilo, Professional Learning Weekend, Sponsorship & Advertising Coordinator, Webmaster

RJ Macalalad, Accounting Staff

Rod Catubig Jr., Office Staff

East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS)

Brentville Subdivision, Barangay Mamplasan, Binan, Laguna, 4024 Philippines

Phone: +63 (02) 8779-5147 Mobile: +63 917 127 6460

Satellite Office

39/7 Soi Nichada Thani, Samakee Road, Bangtalad Sub-District, Pakkret District Nonthaburi 11120, Thailand

Breaking Bad... Habits in Science Education: Culturally Responsive Approaches to Teaching Chemistry By Dr. David Knuffke, Ms. Vivian Huang, and Mr. Paul Booth

50 An Action Research Study at an International High School to Improve AP Computer Science A Student Learning Through AI-Driven Feedback By Yohan (John) Kong

53 From Inquiry to Impact: How Action Research Can Transform Your School By Jon Nordmeyer

54 Developing the Professional: Investment in Teachers and Language Learners by South Korean EARCOS Members By Nate Kebbas

58 Embedding Purpose: How Service Learning is Transforming Our Sixth Form By Michael Browning

60 Timely Choices: Modeling Sustainability for Lifelong Learners By Mr. Anshu Verma 62

Sustainability as a Transformative Practice: Connecting Art and Environmental Awareness By Catherine Traicos

64 Moonlight: Looking for a Life-Changing Educational Adventure for Your Students?

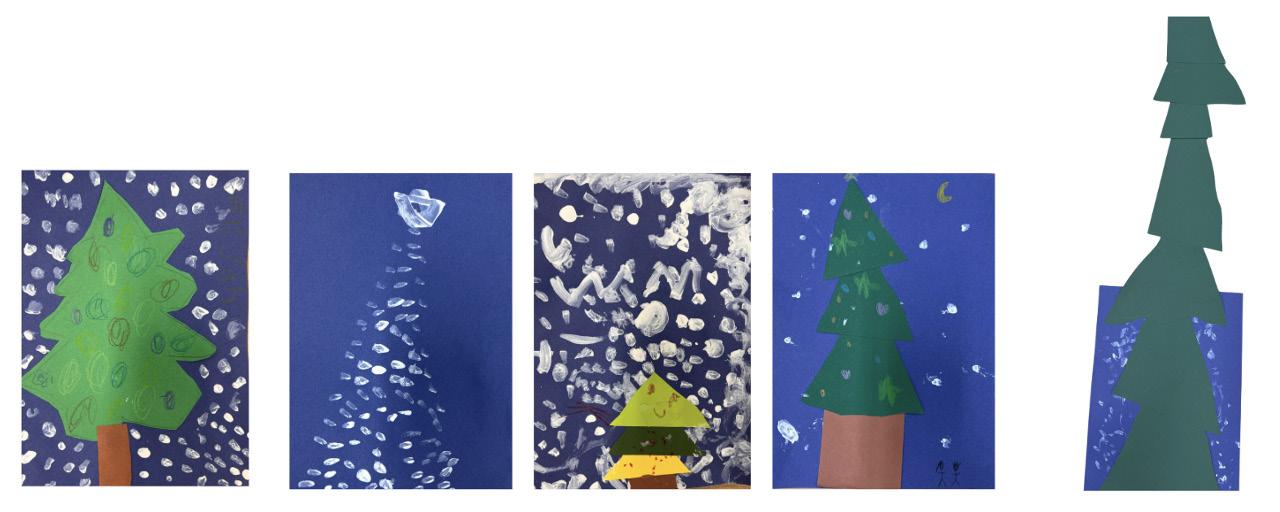

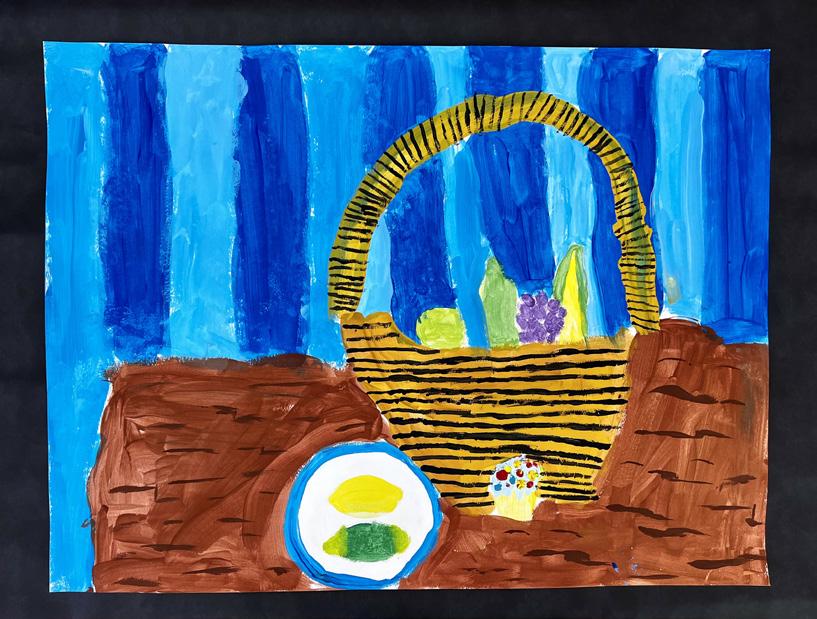

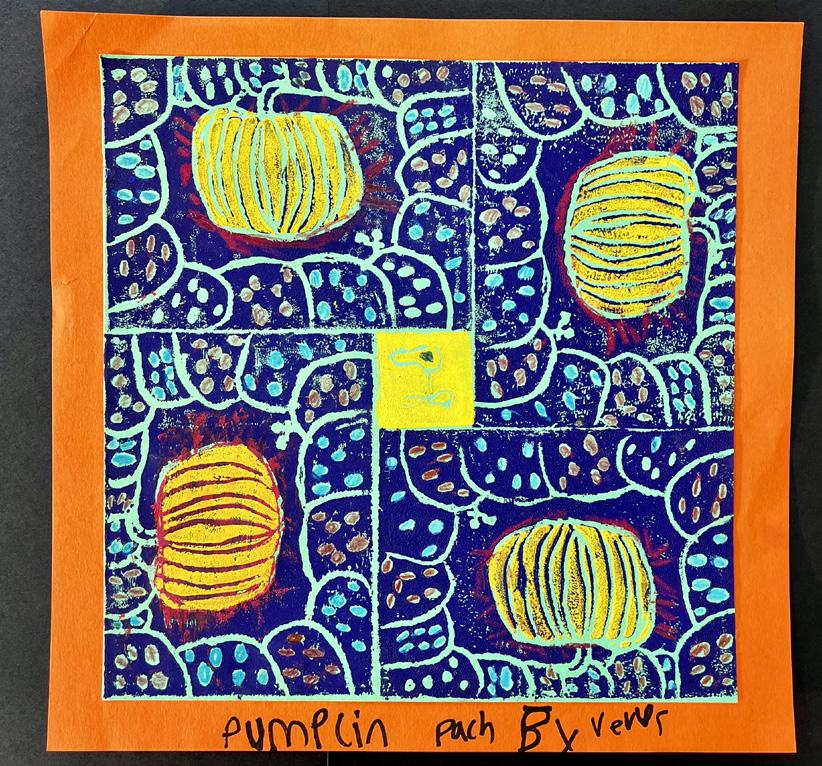

66 Elementary Art Gallery

- Busan Foreign School

- International School Ulaanbaatar

- Mt. Zaagkam School

Global Citizenship Community Service

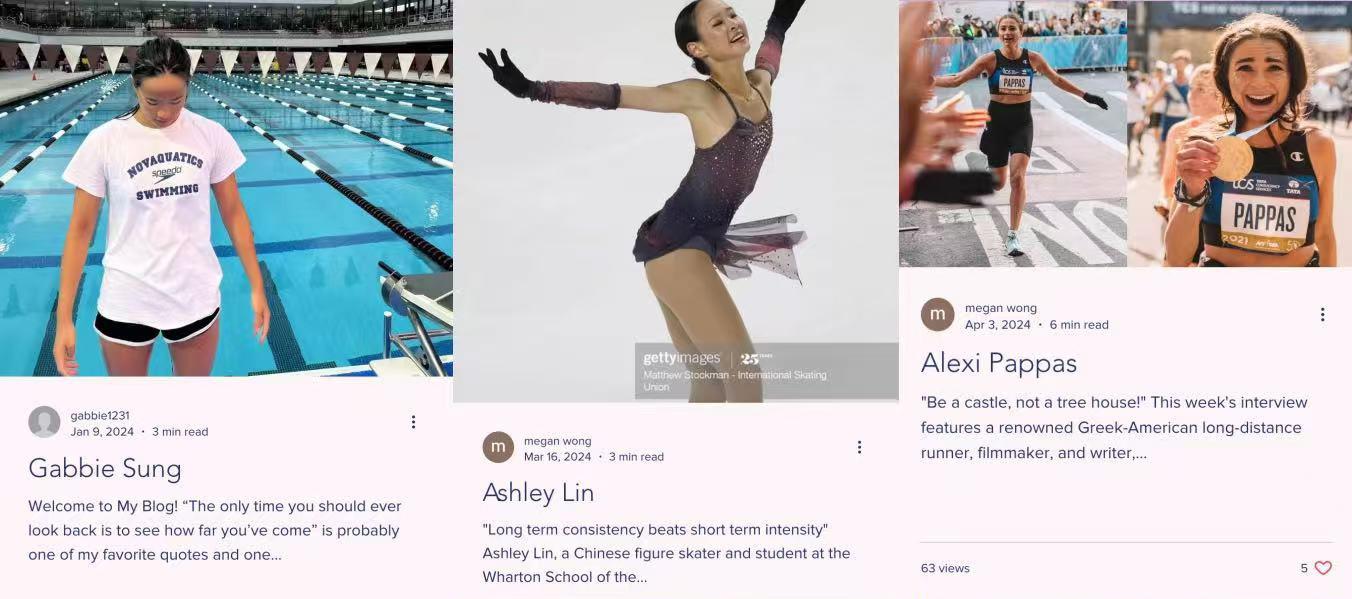

Rise & Thrive By Megan Wong (page 49)

Our New Chapter-Play it Forward By Shian Joo (page 57)

Executive Director’s Message

Greetings and welcome to the first issue of the EARCOS-Tri-annual Journal for the 2025-2026 year. By the time you receive this issue the ‘new’ school year won’t feel so ‘new,’ with memories of what I hope was a restful and productive ‘summer’ holiday now fading a bit too rapidly!

As wonderful as a long summer break may be, it is great to be back in school working together with one another and sharing our days with our students. The energy, happiness and hope one feels when walking past classrooms is something you just cannot find anywhere else. Being an international educator has many benefits, but the greatest gift of all is the remarkably diverse group of students with whom we spend our days. So often we talk about how our classrooms—and our international school communities—are microcosms of the world we strive to create for the future. The future we hope to create seems a very long away some days, I must say.

What we do as international educators all comes back to one simple truth—it is always and only about the students. Our students look to us for the guidance, the support, the understanding, the respect and, yes, the love, they need to step with confidence into tomorrow. Which leads me to ask you to consider the following.

The letters DEIB may be out of political favor in some corners, but there is nothing political about what they embrace. Diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging remain quintessential to the mission of education—just as they were for decades before DEIB became a lightning rod. As educators, we need to go beyond fraught politics and double down on the commitment we made to our students when we became educators in the first place—the commitment to create learning communities where everyone is welcome, where everyone is included, and where all are nurtured and respected for who they are and who they can and will become. This is what it means to deliver on our promise to the young people whose futures have been entrusted to us. This is the heart and soul of an international school. This is what we at EARCOS strive to support.

In this regard, I’d like to remind you that what you do in your school setting resonates deeply with your colleagues all across this vast region. We all share a vision and purpose. So, please, use this journal, your journal, to share your ideas, your initiatives, and the solutions you have implemented to create the school your students need and deserve. We look forward to hearing from you.

Wishing you and your students a wonderful school year ahead.

Edward E. Greene, Ph.D. Executive Director

Dates, Deadlines, & UPCOMING EVENTS

GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP AWARD

APPLICATION DEADLINE: MAY 15, 2026

This award is presented to a student who embraces the qualities of a global citizen. This student is a proud representative of his/her nation while respectful of the diversity of other nations, has an open mind, is well informed, aware and empathetic, concerned and caring for others encouraging a sense of community and strongly committed to engagement and action to make the world a better place. Finally, this student is able to interact and communicate effectively with people from all walks of life while having a sense of collective responsibility for all who inhabit the globe.

GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP COMMUNITY SERVICE GRANT

APPLICATION DEADLINE: JULY 15, 2026

Students designated by their schools as a Global Citizen are eligible to apply for one of six $500 Community Service Grants. These grants are awarded to Global Citizens who are actively involved in a service project benefiting either children, adults, or the environment. The grant is intended to enhance and support the student’s continued efforts with the project during the final year of high school. Interested students are asked to work with their high school principal or designated faculty advisor to complete the application which is found below.

THE RICHARD T. KRAJCZAR HUMANITARIAN AWARD

APPLICATION DEADLINE: JUNE 1, 2026

The EARCOS Board of Trustees has established the Richard T. Krajczar Humanitarian Award to recognize, each year, the work of one not-for-profit organization with a proven record of philanthropy in the East Asia/Pacific Region.

For more information please visit the earcos.org website.

ELM MENTORSHIP

Those interested in joining the program as mentors or mentees are invited to complete the registration and preference ELM questionnaire. Registration for the program is ongoing at https://tinyurl. com/tae2jqz

SPONSORED WEEKEND WORKSHOPS

Teach Students to Be Better Writers by Teaching with Mentors

October 4- 5, 2025

The International School of Kuala Lumpur

Consultant: Carl Anderson

Format: In-Person

Coordinator: Azra Pathan, apathan@iskl.edu.my

Seeing the Whole Student: Data, Storytelling, and Wellbeing Equity

October 18- 19, 2025

Dulwich International High School Suzhou

Consultant: Matthew Savage

Format: In-Person

Coordinator: Murdoch Ian Mackay, murdoch.mackay@dulwich.org

BASIS International School Bangkok

Changchun American International School

King Mongkuts Institute of Technology Ladkrabang Demonstration School

Le Jardin Academy

Welcome New Schools >> Welcome

New Heads >>

Australian International School Vietnam

Bali Island School

Beijing World Youth Academy

Forest City International School

Fukuoka International School

Georgia School Ningbo

Hanoi International School

Hillcrest International School

King Mongkuts Institute of Technology

Ladkrabang Demonstration School

Korea International School-JeJu Campus

Le Jardin Academy

Myanmar International School

Sekolah Pelita Harapan-Kemang Village

Jon Standen

Richard Reilly

Hong Wang

Fred Li

Matthew Kimber

Cavon Ahangarzadeh

Bradley Ringrose

Valerie Johnson

Marc Bourget

Patrick Carroll

Earl T. Kim

Linda Howe

Dale Wood

TH School, Hanoi

Thai International School

Myanmar International School Yangon

Shenzhen Foreign Languages GBA Academy

Shenzhen Shekou Int'l School

St. Mary’s International School

TH School, Hanoi

Thai International School

THINK Global School

True North International School

United Nations Int'l School of Hanoi

United World College of South East Asia

UWC Thailand International School

Wesley International School

Western Int'l School of Shanghai

Yokohama International School

Welcome New High School Principals >>

Ascot International School

Asia Pacific International School

Australian International School

Australian Int'l School Vietnam

Avenues Shenzhen

Bandung Alliance Intercultural School

Beijing World Youth Academy

Branksome Hall Asia

British School Manila

Canadian Int'l School - Vietnam

Canadian Int'l School Bangalore

Canadian Int'l School of Singapore

Canggu Community School

Chinese International School Manila

CIA FIRST International School

East-West International School

Ekamai International School

Forest City International School

Georgia School Ningbo

Gyeonggi Suwon Int'l School

Hanoi International School

Hillcrest International School

Hong Kong Academy

Hsinchu County American School

Hsinchu International School

International School Manila

International School of Busan

International School of Qingdao

Gary Craggs

Alix Kasmarick

Peter Ellis

Lee Childs

Corey Watlington

Elizabeth LaMertha

Robert Wang

Morgan Murphy

Mark Attwood

Tim Ward

Kevin Thomas

Peter Fremaux

Charlotte Hulks

Martin Frias

Jerome Banks

Evangeline Villagonzalo

Karl Snell

Fred Li

Daniel Viccars

Stuart Evans

Clare Gibbings

Steve Bilimek

Joanna Crimmins

Jeff Buscher

Samuel Livingston

Justin Alexander

Paul Horkan

Justin Crull & Julio Morales

International School Suva

King Mongkuts Institute of Technology

Ladkrabang Demonstration School

Korea Kent Foreign School

Nansha College Preparatory Academy

Oasis Int'l School - Kuala Lumpur

Saigon South International School

Sekolah Pelita Harapan Lippo Village

Shanghai Qibao Dwight High School

Shenzhen Foreign Languages GBA Academy

Singapore American School

St. Joseph’s Institution International

Stamford American Int'l School

Surabaya Intercultural School

Suzhou Singapore Int'l School

Terry Linton

Greg Smith

Andrew Davies

Tom Prado

Jen Buchanan

Gerald Schoen

Liz Gale

Nick Alchin

David Griffith

Hope Kim

Jeremy Williams

Carla Marschall

Olivia Ayes

Marc Bourget

Justin Barg

Jay Langkamp

Meganne Benger

Daniel Smith

Levi Bollinger

Michael Coury

Stuart Simpson

Darnell Fine

Oonagh McGarrity

Courtney Malone

George Santiago

Jason Lusby

The American School of Bangkok - Kyle Bilodeau

Green Valley Campus

The Sultan’s School

Tokyo West International School

True North International School

UWC Thailand International School

VERSO International School

Western Academy of Beijing

Western Int'l School of Shanghai

Yew Chung International School of Beijing

Yew Chung International School of Chongqing

Sarah Newton

Sockchong Han

Gerald Schoen

Alice Greenland

Giles Pinto

Jaime Pustis

Greg Peebles

Chris Jarrett

Garry James

Chayaphol Leeraphante

Welcome New Middle School Principals >>

American International School Hong Kong

American School in Taichung

American School of Bangkok, Sukhumvit (XCL)

Australian International School

Australian International School Vietnam

Avenues Shenzhen

Bandung Alliance Intercultural School

Beijing International Bilingual Academy

Branksome Hall Asia

Brent International School Subic

Canadian International School - Vietnam

Canadian International School of Singapore

Carmel School

Forest City International School

Georgia School Ningbo

German European School Singapore

Grace International School

Hanoi International School

Hsinchu County American School

International Christian School - Hong Kong

International School Dhaka

International School of Busan

International School of the Sacred Heart

Korea Kent Foreign School

Jennifer Betram

Sara Hall

Mechum Purnell

Peter Ellis

Lee Childs

Corey Watlington

Elizabeth LaMertha

Meredith Phinney

Matthew Johnson

Trevor Cory

Tim Ward

Peter Fremaux

Rachel Friedmann

Fred Li

Johann Schonken

Travis Klump

Martin Choi

Ms. Clare Gibbings

Jeff Buscher

William Schroeder

Steven Ellis

Paul Horkan

Karen Wilson

Justin Barg

Lanna International School Thailand

Nansha College Preparatory Academy

NIST International School

NIVA American International School

Oasis International School - Kuala Lumpur

Oberoi International School

Renaissance International School

Ruamrudee International School

Matthew Whitwel

Joseph Pomainville

Stuart Donnelly

Reuben Budayao

Travis Copus

Will Hurtado

Stephen Isaacs

Mark Dominguez

Sekolah Pelita Harapan Lippo Village Eseta McIntyr

Shenzhen Foreign Languages GBA Academy

Stamford American International School

Surabaya Intercultural School

Suzhou Singapore International School

Stuart Simpson

Jim Slaid

George Santiago

Jason Lusby

The American School of Bangkok - Kyle Bilodeau

Green Valley Campus

The International School of Kuala Lumpur

True North International School

UWC Thailand International School

VERSO International School

Kyle Martin

Gerald Schoen

Michael Sheridan

Giles Pinto

Yew Chung International School of Qingdao Ves Ivanov

Yew Chung International School of Shanghai Ian Lee

Welcome New Elementary School Principals >>

Ascot International School

Avenues Shenzhen

Beijing International Bilingual Academy

Beijing World Youth Academy

Brent International School Manila

Brent International School Subic

Canadian International School Bangalore

Canadian International School of Singapore

Canadian International School, Tokyo

Carmel School

Chatsworth International School

Cheongna Dalton School

Christian Academy in Japan

Dulwich College Suzhou

East-West International School

Forest City International School

Green Oasis School / Shenzhen Oasis Int'l School

Hanoi International School

Hillcrest International School

Hsinchu County American School

International School of Ulaanbaatar

K. International School Tokyo

Keystone Academy

Korea Kent Foreign School

Kunming International Academy

Nagoya International School

NIST International School

NIVA American International School

Panyaden International School

Renaissance International School

Sekolah Pelita Harapan Lippo Village

Shenzhen Foreign Languages GBA Academy

Lisa Thorpe

Corey Watlington

Lynne Morrin

Timothy Sharpe

Lenore Baldwin

Trevor Cory

Chris Mockrish

Johnathan Daniels

Matt Christie

Rachel Friedmann

Kelley Benjamin

Jason Baker

John Van Hofwegen

Nick Casey

Justin Bisiker

Undrea Conley

Carel West

Lara Johnston

Leanna Doran

Nathan Bryant

Regine De Blegiers

Matthew Archer

Marcelle van Leenen

Justin Barg

Rajan Chana

Mihoko Chida

Kimberley Connlin

Alexander de Guzman

Kathryn Mills

Rachel Mcleod

Yuniarti Kat

Leda Cedo

Shenzhen Shekou International School

Surabaya Intercultural School

Suzhou Singapore International School

Thai International School

Erin Threlfall

Yasoda Deva

Stacy Molnar

Maksymilian Crawford

The American School of Bangkok - Tanya Sweeney

Green Valley Campus

The British School New Delhi

The International School Yangon

The Sultan’s School

Tohoku International School

Vientiane International School

Yangon International School

Nicola Mary Matthews

Geoff Heney

Stephen Braithwaite

Tayla Morro

Elizabeth Overby

James Joubert

American School of Bangkok, Sukhumvit (XCL) Rebecca Carter

Australian International School

Australian International School Phnom Penh

Avenues Shenzhen

Brent International School Manila

Brent International School Subic

Canadian Academy

Concordia International School Shanghai

Dominican International School

Dulwich College Suzhou

German European School Singapore

Hong Kong International School

International School Manila

Welcome Early Childhood Principals >> Welcome

Stuart Armistead

Zoe Heggie

Corey Watlington

Lenore Baldwin

Trevor Cory

Heikki Soini

Shannon Keane

Nick Casey

Anna Ciezczyk

Elizabeth Elizardi

Anissa Eglington

International School of Dongguan

Lanna International School Thailand

Nagoya International School

Renaissance International School

Sekolah Pelita Harapan Lippo Village

Shanghai American School

Thai International School

Thalun Int'l School Learning Leader

Jamie Nelson

Amy Ramsey

Mihiko Chida

Sharmila Ramesar

Kathleen Yi

Sonia Barghani

Maksymilian Crawford

The American School of Bangkok - Tanya Sweeney

Green Valley Campus

True North International School

Vientiane International School

New Associate Institutions >>

ABRSM

www.abrsm.org

Service offered: Assessment (music exams), publishing (sheet music), Digital resources, Teacher & curriculum support.

Alma Student Information System

www.getalma.com

Service offered: Student Information System, School Management System.

ANZUK Education

https://anzuk.education/au/

Service offered: Education recruitment services.

AssessPrep

https://www.assessprep.com/

Service offered: Digital Assessment Platform for all Schools/Ed-tech SaaS.

Building Capacity Education Services

www.aubreycurran.com

Service offered: Customized consultancy and professional development opportunities.

Chapters International

www.chaptersinternational.com

Service offered: Professional Development.

Class Wizard

www.classwizard.ai

Service offered: Assessment automation fully integrated with leading LMS platforms.

Eblana Learning

www.eblanalearning.com

Service offered: Professional development.

Edusfere

https://edusfere.com/

Service offered: Curriculum Development, Mapping and Management Software Platform.

Flint

https://www.flintk12.com/

Serviced offered: AI software for students and teachers.

Global Philanthropic

https://globalphilanthropic.com/

Harvard Graduate School of Education

https://www.gse.harvard.edu/professionaleducation

Service offered: Professional development programs led by Harvard faculty on campus and online.

Instructure Australia Pty Ltd

www.instructure.com

Service offered: EdTech Provider/Software.

JUMP! Foundation

https://jumpfoundation.org/

Service offered: Experiential Education.

Leo Capital Corp (Hong Kong)

Limited https://leowealth.com/

Service offered: Wealth Management, Investments, Tax Planning & Preparation, Insurance, Retirement Planning Services.

Limewing Talents UK

https://www.limewing.co.uk/

Service offered: Recruitment a Service Provider.

Terri Pham

Elizabeth Overby

Macmillan Learning

www.macmillanlearning.co.uk

Service offered: Advanced Placement Qualification Textbook and Digital Resource Publisher.

Metrics China

www.metricschina.com

Service offered: MAP assessments supplier in China/K-12 English original audiobooks/English speech recognition technology.

Moreland University www.moreland.edu

OBELAS

https://obelas.com/

Service offered: EdTech, Publisher of K12 Curricula.

Otus

https://otus.com/

Service offered: Information Technology.

PowerSchool

www.powerschool.com

Service offered: K-12 Education technology.

Prevention Ed www.preventioned.org

Service offered: Alcohol and other drug prevention.

Progression

thailandclimbing.com

Service offered: Outdoor Education Programs and Executive coaching/team building.

Sr. Jean Bergado, O.P.

Ma. Zenaida R. De Guzman

Samsung Electronics (Southeast Asia & Oceania)

www.samsung.com

Service offered: Immersive learning experience via Samsung Tablets and Electronic Boards.

Schoolata

www.schoolata.com

Service offered: Market intelligence for schools.

SchoolSuite

schoolsuite.com.au

Service offered: Unlock limitless possibilities with SchoolSuite's headless Content Management System.

SMART Technologies ULC

smarttech.com

Service offered: Manufacturer of Interactive Flat Panels and Learning Software.

SmileTax

https://smile.tax

Service offered: US tax preparation and filing for expats.

TeachUp

www.teachup.org

Service offered: Child Safeguarding, Student Wellbeing and Professional Development.

Terralabz

https://www.kidzinkdesign.com/terralabz Service offered: Terralabz delivers bespoke lab design, manufacture, and installation.

University of Hawaii - West Oahu https://westoahu.hawaii.edu/

University of Saint Joseph https://www.usj.edu.mo/en

Veracross

www.veracross.com

Service offered: School Information System designed exclusively for K-12 independent schools.

Verkada

verkada.com

Service offered: Physical Security Manufacturer.

Virtually ConnectEd

www.virtuallyconnectedu.com

Service offered: Virtual Special Education and Support Services.

Wellio Education

https://www.wellioeducation.com/

Service offered: Customisable wellbeing program with 300+ editable lessons, interactive delivery, and real-time data to inform planning and parent reporting.

Wide Eyed Tours

www.wideeyedtours.com

Service offered: Tailor made educational trips for school and university groups in SE Asia

Widgit Software

widgit.com

Service offered: Symbols-based communication software and resources for education.

World Volunteer

http://world-volunteer.com/

Service offered: Outdoor/experiential education provider focused on service-learning

Yew Chung College of Early Childhood Education https://www.yccece.edu.hk/en

zenda Technologies Middle East Ltd. https://www.zenda.com/

Service offered: zenda is a specialist financial technology partner to schools, colleges & nurseries, building products exclusively for the education sector.

Seewhere ISScantake

Global Citizenship Awardees >> List of Global Citizenship Award 2025 Winners

This award is presented to a student who embraces the qualities of a global citizen. This student is a proud representative of his/her nation while respectful of the diversity of other nations, has an open mind, is well informed, aware and empathetic, concerned and caring for others encouraging a sense of community, and strongly committed to engagement and action to make the world a better place. Finally, this student is able to interact and communicate effectively with people from all walks of life while having a sense of collective responsibility for all who inhabit the globe.

Access International Academy Ningbo Huaizhou Zhang

American Int'l School Hong Kong

Keertidha Sundar Sundar

American Int'l School of Guangzhou Zhan Yi Willard Mou

American School Hong Kong Ngo Yan Valiant Leung

American School of Bangkok, Sukhumvit (XCL) Ravikarn Dechkerd

Ayeyarwaddy International School Kyi Phyu Ye Soe

Bali Island School

Bandung Alliance Intercultural School

Justine Soline Blanche

Angelique Kezia Chandra

Bandung Independent School Ardelle Yuditama

Bandung Independent School Rani Simanjuntak

Brent International School Manila Joshua Ethan Fulo

Brent International School Subic Seung Won "Andy" Min

British School Manila Beatrice Lim

Busan Foreign School

Canadian Academy

Jaeun Joy Cho

Aimi Kaarina Palmu

Canadian Int'l School Bangalore Haengbok Jang

Canadian Int'l School of Hong Kong

Canadian Int'l School of Singapore

Gabriella Pippa Chan

Deepanwita Agarwal

Canadian Int'l School, Tokyo Yuna Kanno

Canggu Community School Bo Beckman

Cebu International School Raya Leigh Besido

Chatsworth International School

Christian Academy in Japan

Akshit Govil

Daniel Shew

Concordia International School Hanoi HyeIn Jeon

Concordian International School Thanakorn (Burger) Sajjavarodom

Daegu International School Leanne Yoon

Dalian American International School Chih-Ming Chen

Dulwich Int'l High School Suzhou Charlotte Gou

Dwight School Seoul

Sara Ball

European Int'l School Ho Chi Minh City Vi Lam Dinh

Garden Int'l School Kuala Lumpur

Hanoi International School

Hokkaido International School

Thomas Lee

Bao Anh (Katy) Phan

Joohye Hwang

Hong Kong Academy Hailey Ho

Hong Kong International School Amber Ting

IGB International School Suhani Chhabra

Int'l Bilingual School of Hsinchu Jo-Yu Huang

Int'l Christian School - Hong Kong Gianna Yee Kwan Chung

Int'l Community School - Singapore Chiara Song

International School Bangkok Chinnapong Kulmanochwong

International School Dhaka Orthy Humaira Afia

Int'l School Eastern Seaboard (ISE) Nico Sakaguchi

International School Manila Manushri Khanderao Gaikwad

International School of Beijing

International School of Beijing

International School of Busan

Jia Lee

Brian Hwang

Jackleen Kim

International School of Dongguan Hoi Yan Yen

Int'l School of Nanshan Shenzhen Yuet Tung (Chloe) Wang

International School of Phnom Penh Mika Arief

International School of Tianjin You Yang Zhao

International School of Ulaanbaatar Binderiya Balgansuren

International School Suva Daniel Grammatico Di Tullio

ISS International School Yang Ye Aung

Jakarta Intercultural School Aditya Chandra

Kaohsiung American School Justyna Yang

KIS International School Kittiwara Seneewong na Ayudhaya

Korea Int'l School-JeJu Campus Hyunseo (Anthony) Kim

Korea Kent Foreign School Ria Jeong

Lanna International School Thailand Aswin Tantinipankul

Marist Brothers International School Michelle Ranni

Medan Independent School Sienna Gaetano

Mont'Kiara International School Thien Cat Van Nagoya International School Maya Bashore

Nanjing International School Kirsten Joyner

Nansha College Preparatory Academy Junrui "Ray" Deng

NIST International School Sento Ueoka

Osaka International School Lu He Rikuto Hong

Panyaden International School Olamide Phachara Lawal

Prem Tinsulanonda Int'l School Chue (Clio) Sandi

Ruamrudee International School Voranan Puengchanchaikul

Saigon South International School Aruzhan Zatayeva

Saint Maur International School Rosa Maekawa

Seisen International School Risako Tai

Sekolah Ciputra Ezekiel Wondo

Seoul Foreign School Kate Han

Seoul International School Dyne Kim

Shanghai American School - Pudong Campus Ziyue (Mackenzie) Zhu

Shanghai American School - Puxi Campus Sophia Qing'ao Li

Shanghai Community Int'ernationa School - Cho Yen (Audrey) Chiang Hongqiao Campus

Shanghai Community Int'l School - Hector He Pudong Campus

Shen Wai International School Katrina Wong

Shenzhen College of Int'l Education Cisy Tszhei Li

Shenzhen Shekou International School Shian Joo

Singapore Int'l School of Bangkok Proud Prompattanapakdee

St. Joseph’s Institution International Tripti Narula

St. Mary’s International School Yuchan Kim

St. Paul American School Hanoi Haeri Shin

Surabaya Intercultural School Dana Han

Taejon Christian International School Angela Juha Park

TEDA International School Liu Xuan Lin

Thai-Chinese International School

The American School in Japan

Alisa Janechokpinyo

Mirabel Lee

The American School of Bangkok - Su Myint Myat Aung

Green Valley Campus

The Int'l School of Kuala Lumpur

The International School Yangon

United Nations International School of Hanoi

Utahloy International School Guangzhou

UWC Thailand International School

Vientiane International School

Wells International School - On Nut Campus

Western Academy of Beijing

XCL World Academy

Yangon International School

Yew Chung International School of Shanghai

Tommaso Pariani

Pwint Lei Han Kyaw (Anna)

Khue Nguyen

Zijin Cheng

Peiqi Zou

Jiwoo Choi

Anne Fukuura

Chris Liu

Mia Adele Chapa

Ana Julia Schoolman

Angelique Caballero Yang

Global Citizenship Community Grant Recipients >>

All of us here at EARCOS wish to extend our sincere congratulations to the following Global Citizens who have been chosen to receive an EARCOS Global Citizen Community Service Grant of $500 to further their excellent community work during this upcoming academic year. The recipients are:

SCHOOL

Cebu International School

Concordia International School Shanghai

International Bilingual School of Hsinchu

International School Bangkok

International School Manila

NIST International School

Shenzhen Shekou International School

STUDENT NAME

Raya Leigh Besido

Megan Wong

Jo-Yu (Joy) Huang

Chinnapong Kulmanochwong (Tim)

Manushri Khanderao Gaikwad

Sento Ueoka

Shian Joo

PROJECT

Yellow Boat of Hope

Rise & Thrive

Chariate: Be Kind to Your Mind

KRU (Knowledge-Respect-Understanding)

Project Shree Shakti (transl. Divine Empowerment)

From Hair to Health: Multidirectional Approach to Cancer Patient Support

Play it Forward

Leading Together for a Stronger Community: Board Chair–Head of School

Partnership

By Rami Madani, Head of School

The

International School of Kuala Lumpur

The relationship between a school’s Board Chair and Head of School is one of the most pivotal in shaping effective governance and effective leadership. When the relationship is built on mutual trust, open communication, and shared purpose, it enables both strategic alignment and resilience. Yet even the most seasoned professionals can encounter subtle relational dynamics, often unspoken and sometimes unintended, that may prevent this partnership from reaching its potential.

A strong, trusting relationship between the Board Chair and the Head of School is not just desirable, it is foundational to effective governance and institutional health. Research on nonprofit and educational leadership consistently shows that clarity of roles, psychological safety, and mutual trust among senior leaders are critical to strategic alignment and long-term success (Carver, 2006; Kouzes & Posner, 2017; NAIS, 2020). A 2019 NAIS Governance Study found that schools with high-performing Boards were significantly more likely to report strong Chair–Head partnerships, which in turn correlated with increased Head longevity, strategic progress, and positive school climate.

This article assumes a mutual interest and willingness on the part of both the Chair and the Head to reflect, learn, and strengthen their partnership with intention. The Chair–Head relationship is not only a matter of mutual trust but also of shared stewardship of the school’s identity and purpose. Both serve as ambassadors of the school’s guiding statements. While the two roles are closely linked, each operates within a distinct ecosystem shaped by different responsibilities, expectations, and sources of pressure. Every Chair–Head relationship has an overall tone, whether strong, moderate, or strained, yet it can shift temporarily with changes in context, personalities, or circumstances, creating moments that either reinforce or challenge the foundation of trust. Recognizing these shifts helps both leaders navigate challenges without overreacting and focus on the long-term health of the relationship.

Below are some dynamics that tend to impact each role in different ways.

From the Chair’s Perspective:

Board Chairs often carry the weight of representing the collective voice of a diverse Board, while also maintaining a productive and respectful partnership with the Head. They may face pressure to appear firm, independent, or even critical, particularly when other trustees expect them to “hold leadership accountable.” This can at times create an internal conflict when the Chair personally trusts the Head but senses that visible alignment may be misinterpreted as bias. With limited proximity to school life and occasional engagement, Chairs are also expected to quickly grasp complex issues and provide strategic input without overstepping into operations. These dynamics can push the Chair to filter or modulate their communication with the Head, particularly when Board politics or stakeholder expectations are at play.

Unlike Heads, many Chairs receive little formal preparation for the relational demands of the role, relying instead on personal experience and informal guidance. The emotional labor involved in holding the Board–Head relationship with integrity can be significant, especially during times of change or challenge.

From the Head’s Perspective:

Heads of School operate in the daily rhythm of the institution, surrounded by students, staff, parents, and a leadership team that looks to them for immediate clarity and emotional steadiness grounded in educational research and the school’s Guiding Statements. They are expected to inspire, protect, and uphold the school’s values while also advancing strategic goals set by the Board. When difficult Board-level issues arise, Heads may at times weigh the value of full transparency with the Chair against the need to maintain a consistent message and leadership stance with their team, particularly when Board pressure could result in changes the Head would not otherwise advocate.

They may also worry that disclosing uncertainty or missteps could undermine their credibility or create unnecessary concern. As both leaders and bridges between operations and governance, Heads often experience the tension of dual accountability, which naturally influences what they choose to disclose, postpone, or frame carefully.

The following tools are designed as reflective resources to foster personal insight, mutual trust, and growth in the Chair–Head partnership.

Part 1: A Starting Point: The Chair–Head Relationship Continuum

This first tool invites you to reflect on the current quality and nature of your working relationship. The goal is not to label the relationship, but to ask: Where are we today, and what is one shift we can make to move toward a more trusting, strategic partnership?

While this table appears at the start of the article, it may not always be the easiest entry point for conversation between the Chair and Head. The usefulness of the continuum depends on the level of comfort in the relationship. Below are some suggested guidelines for using the continuum based on levels of comfort:

• High comfort: Use the continuum openly in conversation. Reflect on strengths and vulnerabilities with candor.

• Moderate comfort: Begin with individual reflections and then share only the aspects that would lead to the most meaningful transformation. Over time, build greater trust in the partnership.

• Low comfort: This may reflect the early stages of a relationship, a setting where more trust is needed, cultural differences in communication, or a preference for more structured dialogue. Low comfort does not necessarily indicate a problematic relationship. In these cases, it may be best to focus on shared goals without explicitly naming the current dynamic or to work with an external coach or consultant to help shape norms and direction.

In many cases, it may be more helpful to begin by individually reflecting on Part 2 (for the Chair) and Part 3 (for the Head) before debriefing together and identifying next steps.

Common Biases That Erode Trust:

In my training experience and conversations with Chairs and Heads, certain cognitive or cultural biases appear frequently and can subtly undermine trust and clarity in the relationship. Here are a few of the most common:

• Confirmation bias: One or both parties notice only the behaviors that support a pre-existing concern or narrative, reinforcing mistrust or skepticism.

• Cultural bias: Assumptions are made based on one’s own cultural norms around hierarchy, authority, communication, or emo-

tional expression, leading to misinterpretation of tone, intent, or boundaries.

• Egocentric bias: Either party assumes that the other has access to the same context or information, and therefore should fully understand their perspective.

• Attribution error: The Head may interpret the Chair’s questioning as a sign of personal mistrust, when it may instead reflect the Chair’s governance role, concerns raised by other Board members, or even a misunderstanding that could be clarified through dialogue.

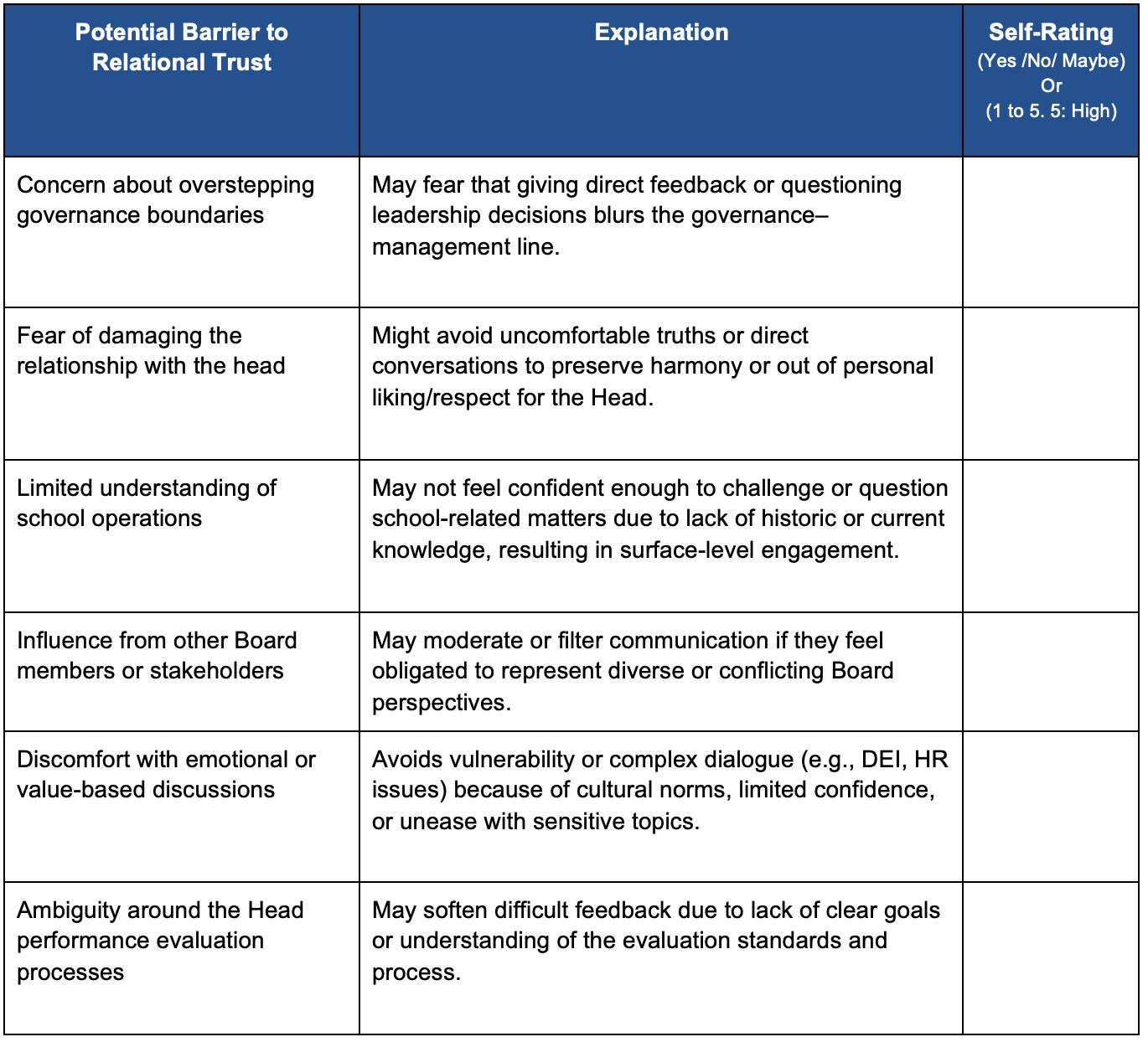

Part 2: Chair Reflection Tool: Relational Trust

This table invites Board Chairs to reflect on factors that might influence how open, transparent, and constructive their communication is with the Head of School. It offers a framework for self-awareness and growth, including a self-rating column to assess the influence of each factor and suggested strategies to strengthen trust and partnership over time.

What might diminish candor between the Head of School and the Board Chair?

Development Strategies for Board Chairs

Below is a list of strategies that may help address areas with lower ratings in the self-reflection above.

The above strategies are not exhaustive. Their effectiveness depends on context, the Chair’s individual preferences, and level of experience. What matters most is choosing approaches that feel both authentic and sustainable.

To move forward, consider reflecting on the following:

• Which barrier resonates most with me at this time?

• What is one behavior or habit I could shift to build more trust in the relationship?

• Who or what might support me in developing this shift; direct conversation, coaching, structure?

• What signalswould indicate that trust and transparencyare improving?

Even small adjustments in awareness or communication can positively influence the Chair–Head partnership. What matters is being intentional and reflective about your next step.

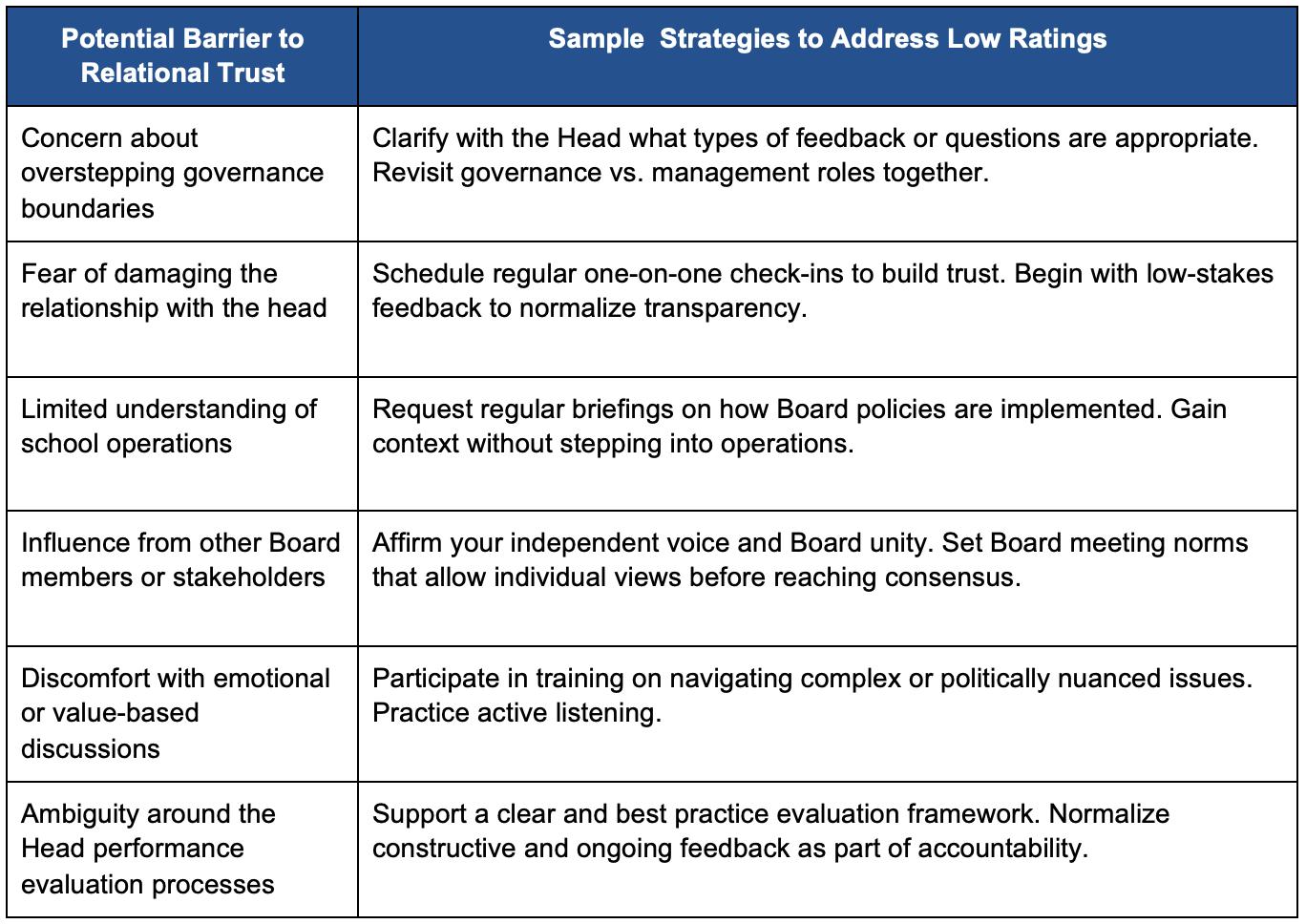

Part 3: Head of School Reflection Tool: Relational Trust

This table invites Heads of School to reflect on factors that may influence how open, confident, and transparent they are in their communication with the Board Chair. It provides a framework for self-awareness and professional growth, including a self-rating column to assess the influence of each factor and suggested strategies to support trust-building and relational clarity over time.

What might diminish candor between the Head of School and the Board Chair?

Development Strategies for Heads of School

Below is a list of strategies that may help address areas with lower ratings in the self-reflection above.

Similarly to Part 2, the strategies above are sample approaches. Each Head may find others that better suit their leadership style, context, or school culture. Given the nature of the relationship, it can be especially challenging for the Head to offer feedback to their supervisor, the Chair. Offering upward feedback can be challenging, especially in governance relationships. While some approaches may require courage, others may begin with small but intentional shifts in communication and mindset. It is always important to consider the impact of the approaches, not just the intent.

To move forward, consider reflecting on the following:

• Which barrier is currently most present in how I interact with the Chair?

• What assumptions or habits might I need to re-examine?

• How can I remain transparent while also protecting the integrity of my team and role?

• What routines or practices could support more consistent and open communication?

• How will I know if trust in the relationship is growing, what will feel different? E.g. less guarded, less misunderstandings, increased willingness to share, or deeper collective thinking.

Building a stronger Chair–Head partnership begins with small moments of clarity, consistency, and ongoing reflection. At the same time, it is important for the Head to remember that a candid and supportive relationship with the Chair does not lessen accountability. The Head’s professional responsibilities, as outlined in the school governance documents, must continue to guide decision-making and communication.

Part 4: A Final Reflection: Trust is Built Intentionally

Trust between a Board Chair and a Head of School does not necessarily emerge through goodwill or time alone. It is cultivated through intentional actions, thoughtful reflection, and honest communication. The relationship grows stronger when both individuals make space to examine their assumptions, acknowledge the pressures they each carry, and remain open to learning with and from one another while maintaining clarity about the reporting line and the purpose of the relationship.

As introduced earlier, it helps to remember that the Chair and Head relationship rests on a baseline tone, whether strong, moderate, or strained,

that can temporarily shift in either direction with changes in context, personalities, or circumstances. Even the most trusting relationships may pass through challenging seasons, just as strained ones may enjoy brief periods of ease. Navigating these shifts with perspective, avoiding overinterpretation, and assuming positive intent can be instrumental in moving through difficult moments.

Each leader operates within a distinct ecosystem. The Chair represents a group that engages with the school intermittently and brings varied external perspectives, while the Head leads within a close-knit educational environment shaped by daily complexities and the emotional rhythm of school life. These contrasting settings influence how each person communicates and what they choose to share.

The tools in this article are designed to encourage reflection, not judgment. They invite both the Chair and the Head to surface what may be unspoken in their relationship and to develop the courage and clarity needed to strengthen their partnership.

Whether used for personal journaling, during a retreat, or in a coaching setting, these resources offer a shared language to support honest dialogue, clarify expectations, and build trust. When this relationship is tended to with care and intention, it can profoundly influence the school’s leadership culture and the health of the broader community.

References

Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation.

Carver, J. (2006). Boards that make a difference:Anewdesign for leadership in nonprofit and public organizations (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Chait, R. P., Ryan, W. P., & Taylor, B. E. (2005). Governance as leadership: Reframing the work of nonprofit boards. Wiley.

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader–member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2017). The leadership challenge: How to make extraordinary things happen in organizations (6th ed.). JosseyBass.

Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 201–227.

National Association of Independent Schools. (2019). Effective governance: Findings from the NAIS governance survey. Washington, DC: NAIS.

National Association of Independent Schools. (2020). The state of independent school leadership 2020: Insights from NAIS governance research. Washington, DC: NAIS.

The Guardian Project From Vision to Action: Protecting What Matters Most

By Robert Landau, Aaron Moniz, and Lauren Jones

In a world increasingly shaped by complexity, uncertainty, and accelerating change, our duty as educators extends beyond preparing students for the future; we must protect the future itself. The Guardian Project emerged from this conviction: that schools and organizations must evolve into places where young people are not only equipped to thrive but empowered to serve, heal, and lead in a world that needs them now more than ever.

Founded in 2025 by a network of global educators, The Guardian Project is a bold, grassroots movement that supports schools in reimagining their purpose through a future-ready framework rooted in real-world relevance, belonging, and courageous leadership.

This article examines how The Guardian Project supports schools and organizations in fostering a sense of belonging, driving change, and empowering students to become guardians of a healthier planet, a more just society, and a more equitable future

Introduction: Education in an Age of Acceleration

We are living in an age of overlapping disruptions. Climate change, social division, threats to public health, and rapid technological shifts are reshaping every aspect of society. As educators, parents, grandparents, and leaders, we must ask: Are our schools keeping pace with the challenges and opportunities our students will face?

For decades, the dominant narrative in education has emphasized preparation, helping students build skills for future college and career success. But what if the real work of school is not only to prepare students for the future but to protect it? What if schools became sanctuaries of stewardship, citizenship, and innovation, not just places of academic development but of purpose, courage, and contribution?

The Guardian Project was founded in response to this question. It is both a call to action and a structured, scalable framework for schools ready to reimagine their purpose and align learning with the most pressing needs of our time. The Guardian Project offers a model of educational transformation rooted in shared values, local agency, and international solidarity.

In Loco Parentis

At the foundation of The Guardian Project is the deeply held human belief that schools are not just institutions of learning; they should be sanctuaries of safety and security. The legal and moral concept of in loco parentis, “in the place of a parent,” has long been a guiding principle of schooling. It reminds us that educators have a sacred duty to protect, nurture, and advocate for the children in their care, especially the most vulnerable. In many communities, school is the safest and most stable environment a child will encounter during the day. It is where they are seen, heard, fed, protected, and loved. The Guardian Project acknowledges this reality by prioritizing student well-being, emotional safety, and a sense of belonging at its core. To be a guardian is not only to educate, but to shield, support, and serve the youngest citizens of our society as they grow into their full potential.

The Guardian Framework: Five Promises for Meeting a Vision

At the heart of The Guardian Project is a learning framework that integrates relevance, responsibility, and resilience. It is built around five core Pillars:

1. Culture & Identity: Helping students understand who they are and how their stories shape how they see and serve the world

2. Civics & Social Justice: Understanding how things work and mentoring students to engage meaningfully in community life and equity-focused action.

3. Stewardship & Global Issues: Inspiring students to care for people and the planet, and to solve global challenges from climate to conflict.

4. Innovation & Entrepreneurship: Encouraging creative problem-solving, design thinking, and new approaches to sustainable impact.

5. Engaged Change-Making: Activating students as leaders, advocates, and builders of a better world—right now, not someday.

These promises are anchored in The Vision that guides project direction and purpose:

• ●Healthy Society

• Healthy Environment

• Healthy Economy

• Healthy Living Things

Rather than being another initiative layered on top of existing priorities, the Guardian Framework acts as a connective tissue that aligns student learning with the real world. It invites every subject, teacher, and student into a purposeful ecosystem of learning that is interdisciplinary, experiential, and grounded in local context.

Building Guiding Coalitions: Transformation from the Inside Out

The journey toward becoming a Guardian Project School begins not with a workshop or a program, but with a commitment to purpose. The first stage is simple yet profound: a school or organization formally joins as a Guardian Member, signifying a

shared commitment to the project’s mission of educating in service of a healthier, more just world. This initial step represents more than affiliation; it reflects a collective understanding that the current trajectory of education must evolve to confront the challenges of our time. Membership opens the door to a growing global network of like-minded schools, educators, and organizations dedicated to transforming learning through the Guardian Framework.

From this foundation, members can begin participating in professional learning, collaborating with consultants and experts who can help them reach the stages of recognition.

However, it all begins with the belief that young people can and must be empowered to protect their future.

This approach to transformation, organic, community-rooted, and human-first, is a deliberate departure from traditional topdown models of reform. Rather than compliance or uniformity, The Guardian Project cultivates creativity and context. Every coalition adapts the framework to fit its own culture, curriculum, and challenges. As a result, implementation looks different in every setting, ranging from large international schools to small rural programs, and from early years to upper secondary education.

Schools are supported by facilitators, coaches, and other Guardian schools who have been through the journey. Coalition teams regularly reconvene to share prototypes, celebrate progress, and refine their designs. Over time, schools begin to see their practices, such as assessment, scheduling, student voice, and community partnerships, shift toward alignment with their renewed purpose.

Recognition: Elevating Purpose Through Evidence of Impact

Recognition within The Guardian Project is not about compliance or ranking; it is about honoring commitment, growth, and contribution. Schools that join as members are invited to embark on a transformative journey, with the opportunity to be recognized across four levels: Emerging, Committed, Exemplary, and Model. These tiers reflect a school’s depth of engagement with the Guardian mission and its demonstrated impact on student learning and community well-being.

Progression is based on authentic evidence, including student projects that address real-world challenges, public exhibitions of learning that engage community stakeholders, and systemic changes within the school that

reflect alignment with the Guardian Pillars and the four futuristic imperatives: health, environment, economy, and living systems. Recognition is not the end goal; it is a reflection of a school’s evolving identity and its courage to lead with purpose.

At the highest level, Model Schools not only embody the Guardian ethos but also serve as mentors to others. They become “Guardians of Guardians,” offering support to schools with fewer resources, both locally and globally, so that the movement for equity and sustainability spreads outward in spirit and action. Recognition becomes a catalyst for deeper partnerships, stronger coalitions, and bolder student leadership. It is both an affirmation and a call to continue the work.

• Emerging: Schools that have formed a coalition and begun aligning practices with the framework.

• Committed: Schools that have implemented at least one full-cycle project or exhibition.

• Exemplary: Schools that have integrated Guardian principles across levels or divisions and demonstrate consistent student engagement.

• Model: Schools that not only embody Guardian values internally but also serve as mentors and partners to other schools, especially those in less-resourced contexts.

Emotional Intelligence and the Inner Life of Schools

True transformation requires more than strategy; it requires emotional intelligence, trust, and a culture of shared purpose. That’s why The Guardian Project invests deeply in coaching, relational leadership development, and strengths-based practices to help educators build self-awareness, resilience, and collaboration.

Workshops often include restorative practices and team-building protocols to ensure that guiding coalitions become not only design teams but communities of care. These efforts ripple outward, shaping faculty culture, student well-being, and family engagement. The result is a school climate where learning is not only rigorous but joyful and humane.

In this way, The Guardian Project embraces change not through pressure or fear, but through connection, storytelling, and the reclaiming of hope.

What Guardian Project Schools and Organizations DO!

At the heart of the Guardian Project lies a belief that knowledge alone is not enough; we must equip and inspire young people to become engaged changemakers Once schools align with a pillar, the next imperative is action. Guardian Schools are called to design learning experiences that go beyond awareness and lead to meaningful, sustained engagement. This involves creating opportunities for students to explore authentic challenges in their communities, collaborate with stakeholders, and propose solutions that are grounded in empathy, innovation, and civic responsibility.

These experiences may begin with small acts of stewardship or advocacy, but should evolve into a scope and sequence of increasingly complex and impactful projects throughout a student’s educational journey. Engaged changemaking is not an add-on; it is the living expression of the Guardian ethos, where students don’t just learn about the world, they learn to protect, serve, and shape it.

But we are doing it already!

Some schools or organizations might ask, “Why the Guardian Project? We’re already doing this work.” That’s excellent news, and precisely the point. The Guardian Project isn’t about claiming originality; it’s about creating connection. There is strength in numbers, and our collective impact will be significantly greater than the sum of our singular efforts. The Guardian network exists to bring together schools, students, and educators who are already engaged in transformative, values-driven education, inviting them to share, support, and amplify each other’s work.

Exemplary schools and organizations have much to contribute, offering mentorship, models, and momentum. Suppose we are to raise a generation of good ancestors and courageous guardians. In that case, we will need many working together, across borders, across systems, and across generations, to make the difference our world truly needs.

Looking Forward: A Movement, Not a Moment

The Guardian Project is not intended to be “one more thing,” but rather a way to bring greater coherence and purpose to what schools already value. Many schools already articulate missions rooted in global citizenship, character development, service, innovation, or social justice.

The Guardian framework helps translate those mission statements into lived experiences by offering a structure for designing authentic, community-connected, and purpose-driven learning. Rather than replacing existing programs, it amplifies them—infusing curriculum with relevance, reigniting student engagement, and helping educators connect what students learn with its significance. When students see themselves as changemakers, and when schools align teaching and learning with values they already espouse, the result is deeper meaning, greater motivation, and a more resilient school culture.

The Guardian Project is still young, but its roots are growing. In an era when educational debates often become polarized or paralyzed, the project offers a hopeful, actionable path forward - one that transcends ideology and centers the learner, the world, and the urgent call of our time.

We cannot predict the future that our students will inherit. But we can prepare them to protect it, with courage, compassion, and creativity. That is the work of a Guardian.

And it starts with us.

For further information about membership, collaboration, and recognition, please go to: https://thegardianproject.net or write to: robertlandau@theguardianproject.net

Academic

Support

Student-Powered Literacy Labs: Building Well-being and Agency Through Peer Coaching

By Joe Schaaf

The International School of Tianjin

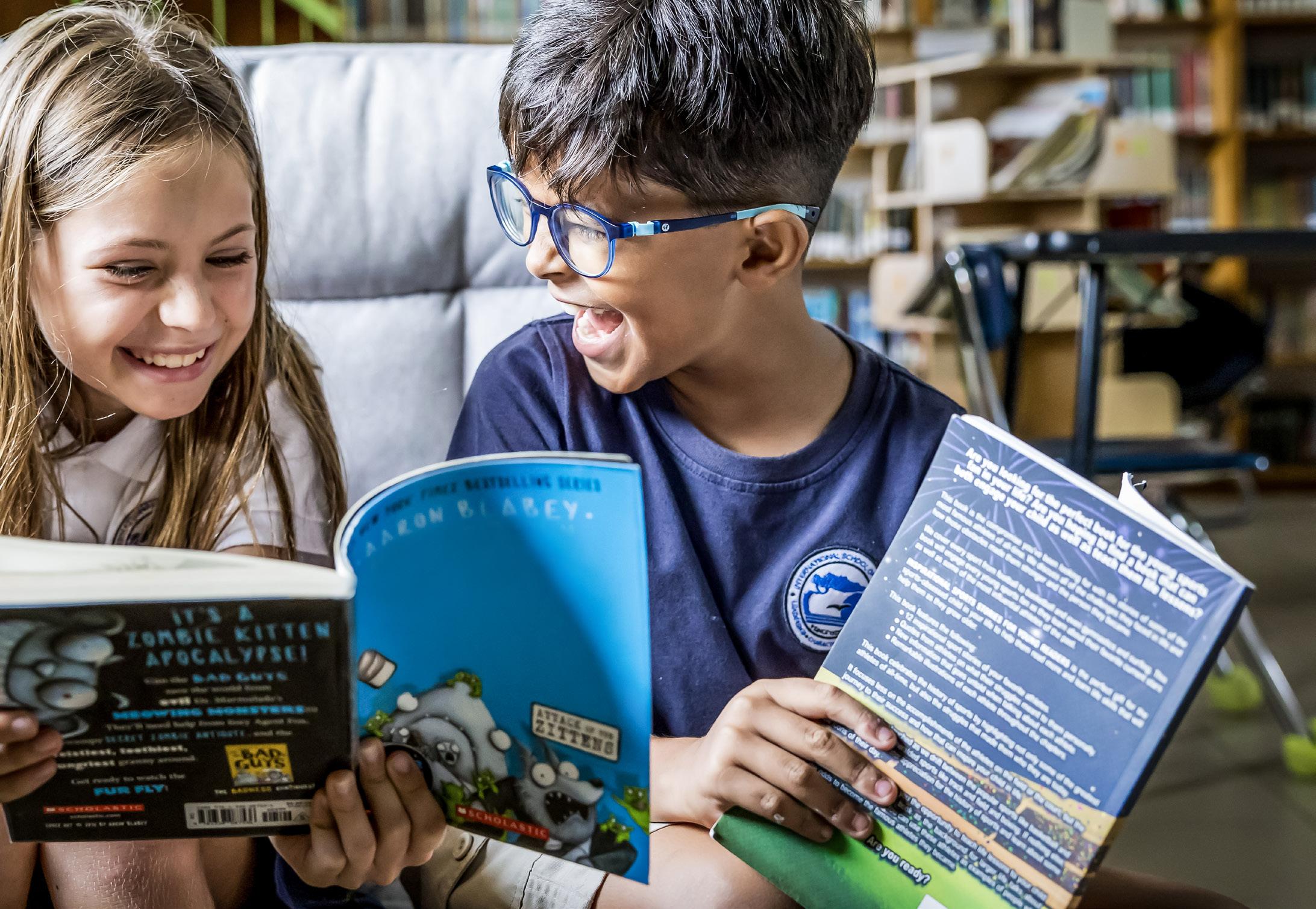

Celebrating its 11th year and more than 1300 annual visits in a school with just over 200 secondary students, the Literacy Lab at the International School of Tianjin is more than an academic support center—it’s a student-powered movement focused on well-being, agency, and a culture of collaborative inquiry. Students visit the Lab for support with writing, reading, note-making, listening, speaking, and presenting—building essential communication skills across disciplines.

Q&A With the Literacy Lab Team

Q: How did the Literacy Lab begin, and what motivated the shift to a student-staffed model?

The Literacy Lab began as a humble writing center in our school library, initially staffed by teachers who volunteered their time to help students. Early on, we recognized that authentic growth happens when students are given ownership and agency in their learning. To make this happen, we shifted toward a peer coaching model inspired by the work of Peter Elbow and Pat Belanoff—one that emphasizes students guiding one another through inquiry and dialogue. This shift brought the Lab to life, transforming it from a drop-in support service into a dynamic hub of student leadership and learning.

Q: How does the Literacy Lab differ from traditional tutoring or writing centers?

Unlike conventional tutoring centers, the Literacy Lab is entirely student-staffed and managed. We do not focus on giving answers or correcting work. Instead, our peer coaches are trained in cognitive coaching and a suite of conferring strategies that focus on process, metacognition, and self-regulation. Our role is to help students ask better questions, listen deeply, and develop the tools to move forward independently. This emphasis on guiding—not advising—supports both literacy development and emotional well-being.

Q: What are the guiding principles that anchor the Literacy Lab’s work?

Our principles are simple but non-negotiable:

• Guide—don’t advise. We never give answers. Instead, we help students discover their own solutions.

• Coach the learner—not the task. Our focus is always on the person and where they are in the learning process, not just the product.

• Make it concrete. We keep discussions grounded in specific, actionable examples—not abstract advice.

• Find the next step. We don’t aim for perfection. We help students find and take their next step.

As coaches, our role is to support learners through the creative process—helping them confront doubt, recognize progress, and take action. Every conversation is a chance to build confidence and capacity.

Q: How does the Literacy Lab actually work during a typical session?

When students arrive, they first choose the conferring strategy they feel comfortable with, which range from low-risk (Listening—No Response) to higher-risk strategies (Criteria-based Feedback). Coaches then guide each session using a structured cognitive coaching approach:

1. Pause – Coaches deliberately pause after the student speaks, giving the student time to think and reducing anxiety.

2. Paraphrase – Coaches briefly restate the student’s words, validating their feelings and clarifying understanding.

3. Probe – Coaches ask open-ended questions (e.g., "What do you think would help you move forward?"), encouraging deeper reflection.

The session ends with the student identifying one actionable next step—ensuring they leave feeling clearer, more confident, and ready to move forward.

Q: How do your conferring strategies build well-being, selfregulation, and agency?

At the heart of our model are ten distinct conferring strategies, each with a different level of emotional risk and metacogitive challenge (see table below). Students always choose which strategy they’re comfortable using—a decisions that empowers them to take only the emotional and cognitive risks they’re ready for. This sense of agency is foundational. Many strategies explicitly prompt students to notice their feelings, confront negative self-talk, and practice positive reframing. Our process helps students name their emotions, reflect on challenges, and develop self-awareness—key aspects of emotional and cognitive wellbeing.

Q: Who’s involved in the Literacy Lab?

We believe anyone can participate in the Literacy Lab—as a coach or a visitor—as long as they can have a genuine conversation with another student. There are no special requirements. If you’re willing to listen, ask questions, and engage sincerely with a peer, you’re welcome in our community. This keeps the Lab open, accessible, and true to our core belief that learning is a shared journey.

Q: What’s involved in training student coaches and leaders? Training is ongoing and community-driven. All coaches participate in workshops on cognitive coaching, focusing on active listening, paraphrasing, and open-ended questioning two times a year. We provide regular skill-building sessions, ongoing feedback, and leadership opportunities for students who take on supervisory and managerial roles. Inclusion is central—any student can participate as a coach or visitor, regardless of background or skill level. We keep barriers low so everyone can contribute, learn, and grow—together.

Q: How does the Literacy Lab help address issues of student health and well-being?

Student well-being is at the heart of everything we do. The Lab gives students meaningful choice—every visitor decides which conferring strategy to use, allowing them to select the level of risk and type of support they feel comfortable with. This autonomy, paired with a supportive peer environment, helps students manage anxiety, build self-trust, and approach challenges with greater resilience. We intentionally design our process to help students name their feelings, practice positive self-talk, and reframe negative thinking through structured peer interactions. Coaches are trained to validate emotions and encourage next-step thinking—not perfection. We also measure impact: after every visit, students complete an anonymous survey. Over 92% consistently rate their sessions at four or five stars. The most common feedback is that students leave feeling more confident, less stressed, and better able to move forward.

Q: What kinds of changes have you seen—in literacy, wellbeing, and student culture?

The impact has been profound. Students report increased confidence, greater autonomy in their work, and a stronger sense of belonging. We see students taking more risks, speaking openly about struggles, and practicing positive self-talk when facing challenges. The Lab’s high usage—over 1300 annual visits in a school with just over 200 students—reflects not just academic need, but a desire for authentic connection. Many former coaches credit their Lab experience for growth in leadership, empathy, and resilience.

Q: How do we know the Literacy Lab helps?

We listen to students and measure outcomes. After every visit, students complete an anonymous survey rating their experience. Over 92% consistently give four or five stars. This year we recorded over 1300 visits—nearly six times the number of students enrolled—a new record. Teachers have also adopted cognitive coaching and workshop strategies in class, with some even visiting the Lab themselves. We’ve also had parents attend our training workshops to help use our strategies to support their students at home. Ultimately, it’s students who tell us if it works—they leave feeling heard, supported, and empowered.

Q: What impact has the Literacy Lab had beyond your own school?

The Literacy Lab has had broad regional impact, presenting at schools and professional workshops across Asia—from Ulaanbaatar to Bangkok. We've hosted two annual regional workshops at the International School of Tianjin and will hold our next one at Shekou International School in Shenzhen September 2025, inviting schools from across the region to engage with our model. We're also developing a comprehensive handbook to help schools start their own student-powered learning centers. Our goal is to make this model rooted in agency, process, and wellbeing accessible to all.

Q: Why is the Literacy Lab especially relevant for the future?

In an age increasingly dominated by artificial intelligence and automated content generation, the Literacy Lab anchors students in what remains distinctly human: process, interaction, and ownership of learning. As AI accelerates the production of polished products, it's easy to lose sight of the deeper, slower work of inquiry, reflection, and iteration. The Lab keeps this process visible. By cultivating dialogue, metacognition, and peer support, it develops the very qualities—empathy, critical thinking, and creative adaptability—that the World Economic Forum identifies as essential for the future of work. In short, the Lab doesn’t just prepare students to create better products; it prepares them to thrive in an unpredictable future.

Q: What practical advice would you offer to schools looking to build a student-powered learning center?

Start small and grow organically. Use a clear process model and simple ground rules: prioritize dialogue, guide rather than advise, and celebrate every step forward. Keep participation open. Avoid excessive requirements. Train students but let them lead. Trust them—they will exceed your expectations.

Table: Ten Conferring Strategies for Well-being & Self-Regulation

These ten strategies—arranged from low to high risk—allow students to take the emotional and cognitive risks they’re ready for. They choose. The agency is theirs.

Strategy Description

1. Listening—No Response

2. Talking It Out

3. Strengths

4. Paraphrasing

5. What’s Almost Said

6. Highlighting

7. Organizing

8. Identifying Problems

9. Doubting

10. Criteria-Based Feedback

Self-Regulation Focus

Share work aloud without feedback. Reduces anxiety, promotes self-reflection.

Talk through ideas while peers ask openended questions. Builds metacognitive awareness.

Peers identify what’s working well. Reinforces confidence and positive selftalk.

Listeners restate what they hear. Validates feelings, clarifies thinking.

Peers identify what's implied or underdeveloped.

Encourages openness and growth mindset.

Peers point out unclear parts. Builds clarity and tolerance for critique.

Feedback on structure and flow. Strengthens planning and flexibility.

Pinpoint areas needing revision. Develops resilience and goal-setting.

Peers challenge weak areas.

Builds critical thinking and emotional tolerance.

Evaluate work using a rubric. Supports acceptance of standards and next steps.

For more information, contact Joe Schaaf at the International School of Tianjin: joe_schaaf@istianjin.org.cn.

About the Author

Joe is the Head of Learning and Teaching at IST and has over 20 years of experience researching, developing, and implementing literacy-based programs. He is responsible for transforming IST’s Literacy Lab from a small, teacher-led writing center into a fully developed, student-staffed and managed learning center. Joe has worked with a wide range of students and professionals across elementary, secondary, and post-secondary settings. He is the author of Exploring Texts: A Guide to Inquiry and leads workshops throughout Asia, with a focus on student agency, process-based learning, and collaborative school culture.

“At a time when we are trying to reduce barriers, create access, and alleviate unnecessary stress on families, the value of the SAO has never been more evident.” QUENTIN MCDOWELL, HEAD OF

Standard Application Online (SAO)

• 55% of parents say applying to independent schools is too stressful.

• 49% say it’s more work than they expected.

• 49% Indicated essays are the most stressful aspect for students.

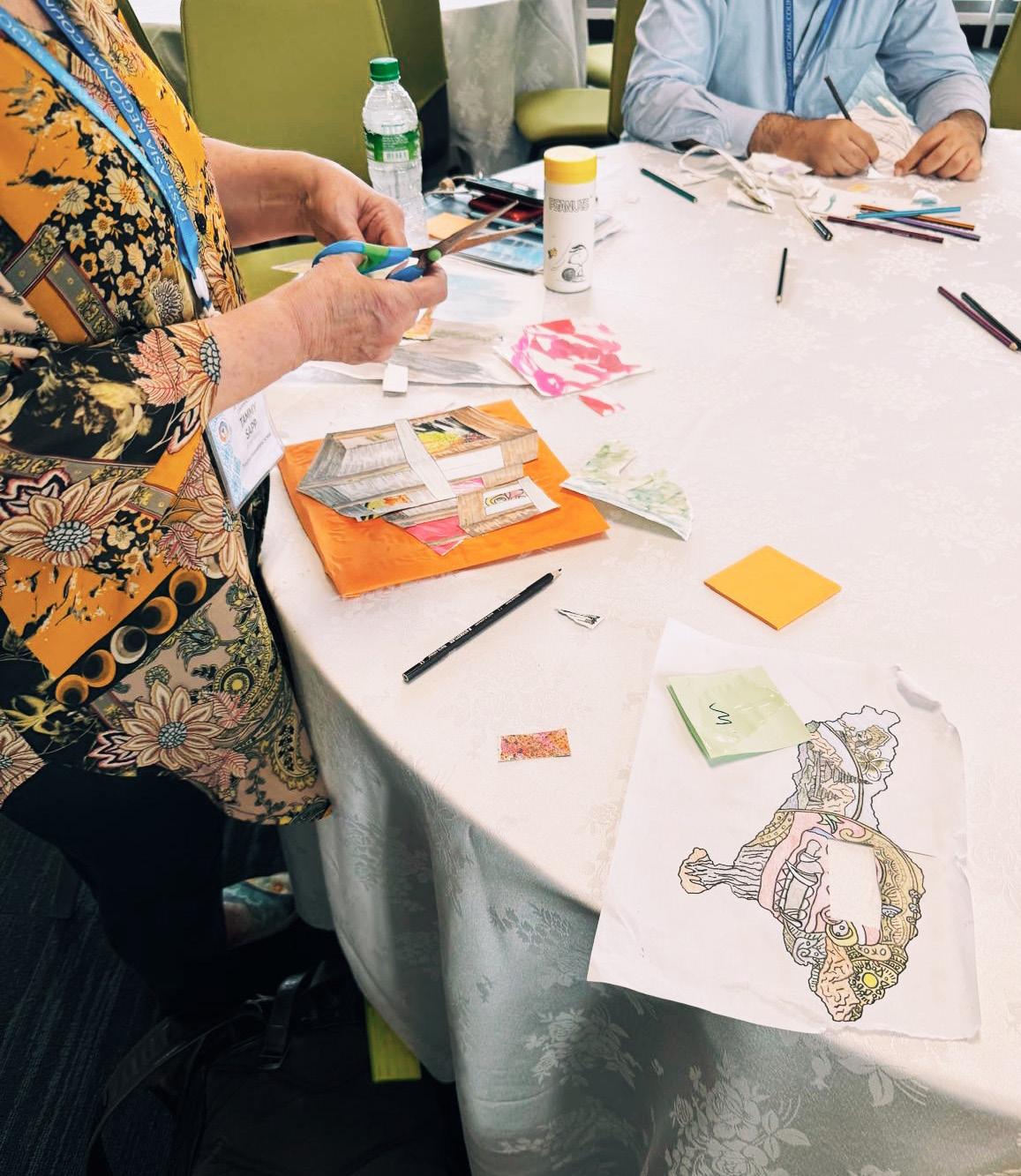

A New Approach to Supporting Creativity in Early Elementary Classrooms

By Ciara Dudley Seoul International School

As you begin to read this article, I would like to invite you to take a moment to pause and consider what creativity means to you. What does it look like when a child is being creative? What does it feel like? How do we know when we are seeing it in our classrooms?

In early childhood education, creativity is not just a desirable trait. It is essential. For young learners, creative exploration supports problem-solving, communication, emotional development, and self-confidence (Isbell & Yoshizawa, 2016). When working with a group of students, I noticed their hesitation to express their own ideas during artistic activities. They often looked to the teacher for the "right" way to do something or to copy an example without experimenting. This observation became the seed for both a presentation at the EARCOS Teachers’ Conference and an action research project in my graduate studies, leading to insights and strategies that help support creative risk-taking in the early years classroom.

In this article, we will look at ideas from said research and work, exploring how open-ended prompts, non-evaluative language, and intentionally designed environments can help nurture creative confidence. You’ll also find practical strategies you can use in your own classroom, especially if you are looking to encourage student voice, choice, and imagination.

Educators exploring materials at EARCOS 2025

What is Creativity in the Early Years?

Creativity in early childhood education goes beyond art projects. It is a way of thinking, trying, exploring, and making meaning. It is the ability to express thoughts or feelings through many different forms, what Malaguzzi called the "hundred languages of children" (Mphahlele, 2019). In young children, creativity can be seen when a child uses materials in unexpected ways, invents a story, or confidently shares a drawing that represents a personal idea.

While presenting at the EARCOS Teachers’ Conference, I opened by asking educators to reflect on what creativity looks and feels like in their context. Teachers shared a variety of powerful responses:

• "Creativity is more than just thinking outside the box— it's thinking what you can do with the box."

• "It looks like kids making stuff, flying, chaos, and personal expression."

• "It feels like excitement, energy, joy, or even intimidation."

• "Creativity is defined by uniqueness, innovation, freedom, and self-driven ideas."

• "It’s the force driving innovation! The ability to imagine something that doesn’t exist and manifest it."

These reflections mirror what we often see in early childhood classrooms and echo the fact that creativity is, at its core, personal, messy, expressive, and powerful.

Building a Creative Environment

A creative classroom is not just about having art supplies on hand. It’s about creating the conditions where creativity can thrive. That means making intentional choices about the physical setup, the materials, and the routines that shape our learning spaces.

Materials: Offer a variety of materials such as paper, paint, clay, fabric, loose parts, recycled items, and natural objects. Children need multiple opportunities to explore different textures and mediums to unlock their imagination (Anggraini & Yuwono, 2022).

Accessibility: Organize your materials in a way that allows children to independently choose and return them. This supports autonomy, responsibility, and creativity (Bae, 2004).

Collaboration: Invite children to co-create shared murals, sculptures, or storybooks. These experiences help them see that creativity can be both individual and communal.

Connection to nature: Bring natural materials into the classroom or take art projects outdoors. Interacting with the environment invites sensory exploration and often inspires new creative directions (Gilmore, 2011).

Open-ended activities: Avoid projects with a single correct outcome. Instead, offer a theme or provocation. Instead of an activity such as “everyone will make the same ladybug by gluing red circles onto black paper and drawing black spots”, an activity focused on following specific steps to achieve a uniform result. A prompt like “Create a creature that lives in your imaginary world. What does it look like? What can it do?” encourages personal interpretation, storytelling, and a variety of creative responses. The students have the choice to use collage, drawing, or con-

struction materials in unique ways.

Reflection and sharing: Provide opportunities for children to talk about their work. Simple routines like a mini art show or a gallery walk help children reflect, take pride, and be inspired by one another.

From Mystery Bag to Masterpiece: Process Over Product

One of the most important shifts we can make as educators is to prioritize the process over the product. During a recent workshop, I introduced a "Mystery Bag Challenge" where teachers received a random set of materials and a creative prompt. Each group produced very different outcomes, showing the participants’ unique ways of thinking and working. The real value was not in what was made but in how it was made.