10 HIDDEN SIGNS YOUR BRAIN MAY BE DEGENERATING 10 HIDDEN SIGNS YOUR BRAIN MAY BE DEGENERATING

If you ' ve watched a loved one gradually decline due to Alzheimer's or another brain-degenerating condition, you know the heartbreak of losing them piece by piece

It starts with subtle changes – misplacing keys more often, losing interest in favorite hobbies, taking a bit longer to find the right words.

But as time goes on, the differences become more pronounced and distressing.

They may get in the car and become totally lost while driving a familiar route. They might recall events that never happened while cherished memories fade. They may see or hear things that aren't there, unable to distinguish delusion from reality

Confusion overtakes a once sharp mind. Their personality may morph, replaced by someone prone to anger, anxiety, hostility, or apathy. They live in a different world, remembering things that didn't happen. And you can't correct them, because that is their reality.

For many families, it feels like a fate worse than death –mourning someone who is physically present but psychologically absent. The emotional toll is immense as you struggle to connect, communicate, and provide comfort. It's a long, painful journey for everyone involved.

And here's what makes it even more tragic: research suggests the brain changes that lead to these devastating symptoms often begin 20-30 years before diagnosis. [1]

The earliest warning signs are so subtle that they're easily dismissed as stress, normal aging, or "senior moments " But they can be important clues that the brain is in trouble.

If we knew how to recognize these clues, we might be able to take action sooner, working with doctors and lifestyle changes to preserve cognitive function and slow decline

We could potentially have more lucid years with our loved ones, delaying the most heartrending stages of the disease

That's why this guide is so crucial.

In the following pages, you'll learn:

The 10 often-overlooked signs that may indicate the brain is changing Simple tools to help you assess concerning symptoms What to expect from a medical evaluation for cognitive concerns Science-backed strategies to support brain health and resilience

This book will empower you with the knowledge and tools to take proactive steps, whether you ' re worried about your own brain health or supporting someone you love. Because even if some degeneration has already occurred, there is still much that can be done to protect and strengthen remaining neural connections.

You are not helpless, and you don't have to wait for a diagnosis to start supporting your brain. Let's get started on this journey to take back control… together.

Before we dive into the signs, let's cover some basics about how brain degeneration occurs

While it's a complex process, having a general understanding can help you better advocate for yourself and make informed decisions.

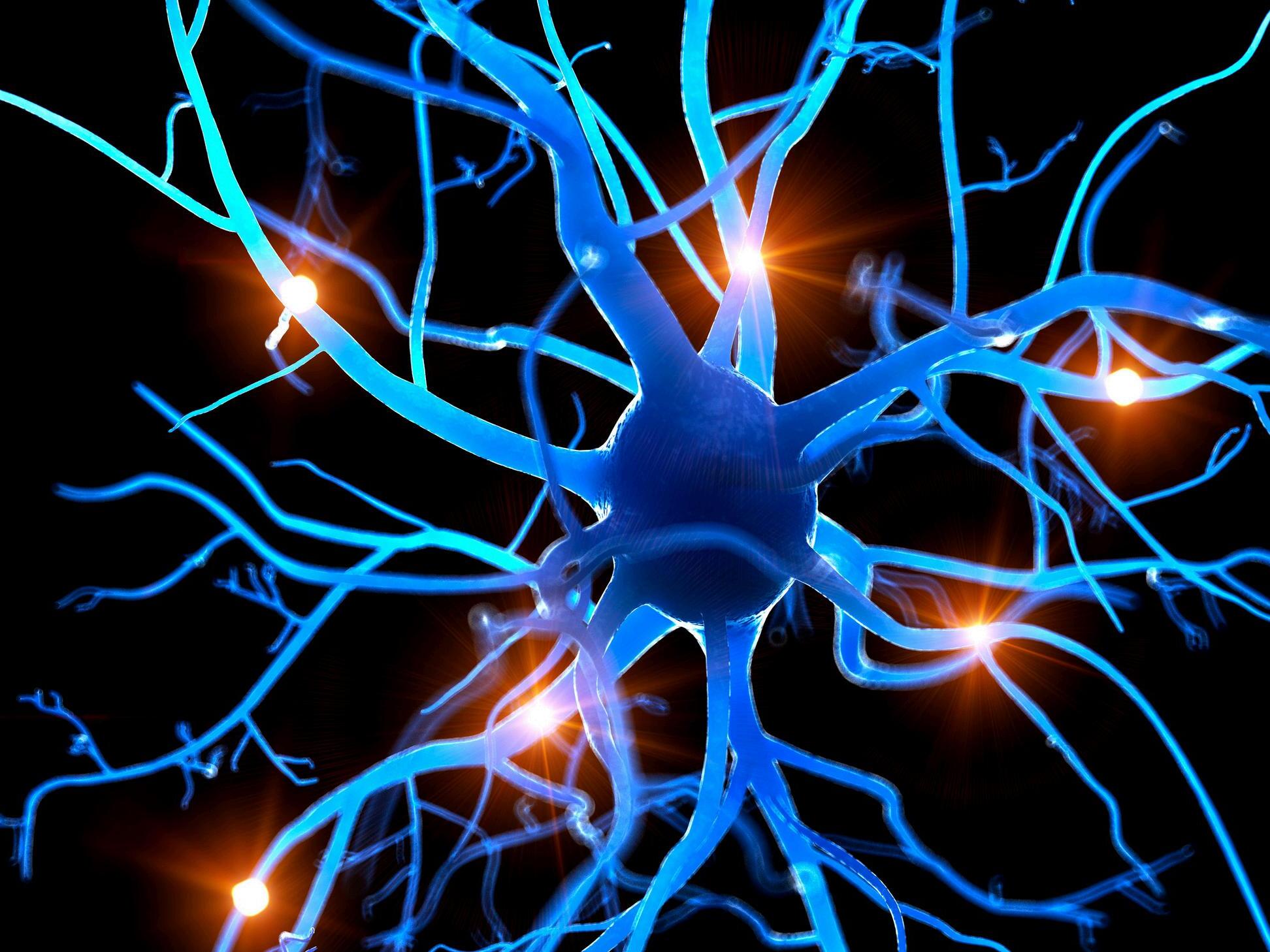

Your brain is made up of billions of nerve cells, called neurons, that communicate with each other via electrical and chemical signals. This communication is essential for everything from movement and speech to learning and memory.

In neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and frontotemporal dementia, these neurons gradually deteriorate and die. This progressive neuron loss impairs the brain's function over time, leading to the cognitive, behavioral, and physical symptoms associated with these conditions.

While the specific causes and disease course vary, neurodegenerative disorders share some common features:

Abnormal protein buildup in and around neurons, impairing cell health and communication

Chronic inflammation, which further stresses and damages brain cells

Decreased energy production in brain cells, making them vulnerable

Loss of connections between neurons, disrupting information relay

In the early stages, your brain can often compensate and find alternate pathways. That's why symptoms may be subtle at first. But as neuron loss accumulates, cognitive and physical problems become more apparent.

While many brain diseases can cause the warning signs we'll discuss, a few key players are responsible for the majority of cases. Here's a quick rundown:

Dementia is an umbrella term for a decline in cognitive function severe enough to interfere with daily life. It is caused by damage to brain cells and is not a normal part of aging. There are many other types, each with distinct features:

Alzheimer's is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of cases [2] It's known for causing progressive memory loss, but often starts with milder symptoms like apathy, disorientation, and word-finding difficulties.

Early-onset Alzheimer's affects people under 65 and tends to progress faster. It's rare, accounting for less than 10% of cases [3]

Late-onset Alzheimer's is much more common, typically developing after age 65 Age is the greatest risk factor [4]

The second most common dementia after Alzheimer's, vascular dementia results from impaired blood flow in the brain due to conditions like stroke, heart disease, and high blood pressure. Symptoms depend on the specific brain areas affected. For instance, damage to the frontal lobe can cause problems with executive function and judgment, while damage to the temporal lobe may impact memory and language

Often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's, Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) has features of both – memory problems and motor symptoms. It also causes unique changes like vivid hallucinations and dramatic fluctuations in attention

Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) is tricky because it typically starts with personality changes, lack of empathy, poor judgment, or language difficulties – not memory loss. It tends to affect younger people, often in their 40s-60s. [5] In later stages, FTD can progress to more global cognitive impairment, including memory loss

Parkinson's is known as a movement disorder, causing tremors, stiffness, and balance issues. But it actually often starts with nonmovement symptoms like loss of smell, constipation, and acting out dreams.

Dementia can also develop in later stages of Parkinson's It affects thinking, memory, and behavior, but is different from Alzheimer's dementia.

While each disease has its own pattern, they all involve the gradual loss of brain cells that leads to the signs and symptoms we'll explore in depth. Identifying these red flags early allows for timely diagnosis and intervention.

But remember, occasional forgetfulness or clumsiness doesn't automatically mean you have a brain disease! Many of these signs exist on a spectrum and can have other causes like stress, poor sleep, medications, or vitamin deficiencies.

That's why it's crucial to look at the overall pattern, track changes over time, and get a thorough medical evaluation if you ' re concerned. We'll delve into assessment tools and proactive steps you can take in the coming chapters.

The scary reality is that neurodegeneration is increasingly common

Over 7 million Americans are living with Alzheimer's today, and that number is projected to more than double by 2050 as our population ages [6]

Parkinson's affects nearly 1 million people in the U.S., with between 60,000 and 90,000 new diagnoses each year. [7]

Lewy body dementia affects an estimated 1.4 million Americans [8]

Now, you may be wondering why these numbers seem higher than in generations past. While this is an area of active research, several factors likely contribute to the increasing burden of neurodegenerative diseases:

Longer lifespans mean more people reaching ages when these conditions commonly develop. For example, the average life expectancy in the U.S. has increased from 68 years in 1950 to 79 years in 2025 [9]

Increased awareness and improved diagnostic tools are identifying more cases Environmental toxins, chronic stress, and unhealthy modern lifestyles may accelerate neurodegeneration in genetically susceptible individuals [10,11,12]

While these facts are sobering, there is also hope Research shows that interventions especially early in the disease course can help slow progression and maintain quality of life longer. [13]

Being alert to the initial signs is key to benefiting from early action.

In the next chapter, we'll explore 10 changes that may be warning signs your brain needs some TLC. If any of them sound familiar, don't panic. Instead, use this knowledge as a catalyst to start giving your brain what it needs to stay resilient and thrive.

You know yourself best. You're the first to notice when something feels off, even if it seems minor.

When it comes to brain health, it's these subtle initial signs that provide the biggest window of opportunity to intervene.

That's why awareness is so crucial.

While it can be tempting to dismiss slight changes as "just aging" or a normal "senior moment," taking them seriously may make all the difference in maintaining your longterm cognitive vitality

As you read through these 10 signs, assess whether you ' ve noticed any in yourself lately.

Also consider whether someone close to you, like a spouse, child or friend, has pointed them out

Sometimes others notice little changes in us before we see them ourselves.

Later on, we'll cover how to bring up concerns with your doctor and steps you can start taking now to nurture your neurons. JASON PRALL

Your sense of smell may seem unrelated to brain health, but it's deeply connected. Your olfactory bulb, which processes odors, is one of the first areas impacted by Alzheimer's often well before memory issues emerge. [14]

In patients with Alzheimer’s, the olfactory bulb has an unusually high number of abnormal clumps of a protein called “tau,” which in healthy brains are responsible for stabilizing microtubules the cell’s internal transport highways But with Alzheimer’s, these proteins build up and tangle in the olfactory bulb and the pathways linking it to memory and emotion centers years before obvious cognitive symptoms appear. This may explain why changes in the sense of smell are often an early clue that something is amiss in the brain. [15]

Impaired olfactory function may look like:

Coffee smelling faint

Perfume/cologne seeming weaker to you than others report

Food tasting “flat” unless it’s very salty or sweet

If fragrances that were once powerful now seem subtle, or you have difficulty naming common scents, take note. It could be a clue that cells in your smell circuitry need support

However, other things may be causing this such as a recent cold, allergies, sinus issues, COVID-related smell loss, smoking, or certain medications So don't panic if your sense of smell seems diminished. Keep track of your symptoms and if they last more than a few months or are showing up alongside other signs in this guide, talk to your doctor.

Micrographia (a medical symptom characterized by abnormally small or cramped handwriting) is a hallmark early sign of Parkinson's. [16] Handwriting relies on fine motor control and automaticity. Early basal ganglia changes (common in Parkinsonian disorders) can make movements smaller and slower As dopamineproducing neurons in this area are lost, it becomes increasingly difficult to control fine motor skills, such as writing.

This may look like:

Signatures look cramped or trail off

Grocery lists tilt or shrink across the page

Writing feels more effortful or tiring than it used to

If your typically tidy penmanship is now smaller and more crowded, or you ' ve noticed your signature getting more compact, it may indicate your brain-hand connection needs some attention

Keep in mind, stress, fatigue, pain, or vision changes can also affect handwriting. But if your writing has noticeably changed and it persists, bring it up with your doctor.

We all have expressive quirks maybe you ' re quick to smile or your brows show exactly what you ' re thinking. Spontaneous facial expression relies on a complex interplay between the motor cortex, basal ganglia, and brainstem.

Damage to these areas or the nerves that control facial muscles can reduce expressiveness, leading to a mask-like appearance, which is often most noticeable in Parkinson's disease [17]

Subtle hypomimia may present as reduced smiling, frowning, or emotional expressivity during conversation, detectable only through careful observation.

So if you or others have noticed your face seems more neutral, blank, or "masked" lately, even when you ' re feeling emotions inside, it could signal changes in the brain regions controlling facial muscles.

Sleep is essential for clearing toxins and repairing neurons. When sleep is consistently disrupted, it can impact memory, mood, and overall brain function.

Vivid dreams, thrashing, or acting out dreams (like kicking or talking in your sleep) can precede Parkinson's and Lewy body dementia by years. [18] This REM sleep behavior disorder (known as RBD) occurs when the brainstem areas that normally paralyze muscles during dream sleep are damaged.

Less dramatic changes like fragmented sleep or daytime drowsiness can also indicate early brain changes, as sleep-wake rhythms are controlled by delicate circuits that are easily disrupted [19]

Other sleep changes that may indicate early neurodegeneration include: Restless legs syndrome, which is more frequent in Parkinson's and often precedes motor symptoms [20]

Frequent distressing dreams/nightmares In older adults, having frequent bad dreams has been associated with an increased 5-year risk of Parkinson’s disease and faster decline in PD cohorts. [21]

Sleep apnea, which is linked to increased risk of dementia, likely due to oxygen deprivation and sleep fragmentation [22]

These changes can reflect disruption in the brain's sleep-regulating centers, such as the hypothalamus and brainstem. They may also be related to underlying changes in neurotransmitter systems, such as dopamine and acetylcholine, which are involved in both sleep and cognition.

It's important to note that sleep disturbances are common and can have many causes besides neurodegeneration, such as stress, medications, pain, and other health conditions. However, if sleep problems persist, worsen over time, or occur alongside other signs of cognitive or motor decline, it's worth discussing with a doctor to rule out an underlying neurological issue.

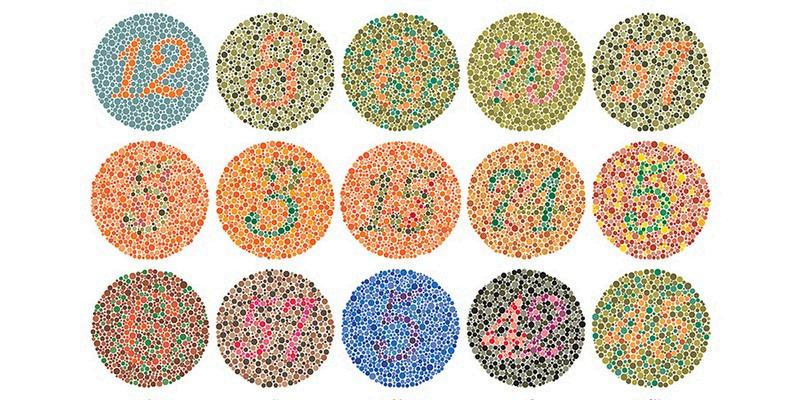

Color vision changes, especially difficulty distinguishing blue from green, can be an early sign of neurodegeneration. This is because the brain's visual processing areas, particularly those involved in color perception, are affected in conditions like Alzheimer's and dementia with Lewy bodies. [23]

Color perception isn’t just about the eye. The retina, optic nerve, and visual cortex all team up to separate hues and detect contrast. Damage to these areas or their connections can lead to subtle changes in color perception, often starting with blues and greens. This is because these cooler colors are processed by similar wavelengthsensitive cells, so they're more vulnerable to early deterioration.

You might notice:

Mixing up close shades (teal vs. green, navy vs. black), especially in dim rooms

Colors on produce, makeup, or clothing looking “washed out” unless lighting is very bright

Needing extra time to read color-coded charts, craft supplies, or spreadsheets

While color vision changes can be an early warning sign, they can also occur with normal aging, certain eye diseases, or as a side effect of some medications If you notice persistent changes in how you see color, especially if accompanied by other visual symptoms like blurriness or blind spots, it's important to get a comprehensive eye exam and discuss your concerns with your doctor.

Misplacing keys or forgetting an appointment can happen to anyone. However, if you ' re noticing a pattern of losing things, struggling to plan, or acting on impulse more frequently, it may indicate changes in your frontal lobe, the area responsible for executive functions.

Executive functions are high-level mental skills that help us plan, focus, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks. They rely on the brain's frontal lobe and its connections to other regions When these neural networks are disrupted by inflammation, lack of sleep, stress, or aging, mental slips become more frequent.

You might notice:

Difficulty planning projects or staying organized

Losing your train of thought more often

Skipping a step in a routine without realizing it

(e g , starting coffee without adding water, leaving the house without your wallet)

Subtle disorganization, such as piles of halffinished tasks, duplicate online orders, or needing multiple reminders to complete a simple errand

Making impulsive decisions or purchases

Saying things without thinking them through Trouble multitasking or paying attention

In early stages of conditions like Alzheimer's or frontotemporal dementia, these changes can be subtle and easily overlooked. You might feel like you ' re not as sharp as you used to be, but chalk it up to stress or aging However, if mental slips start interfering with daily functioning or if loved ones express concern, it's worth getting evaluated.

Walking is so automatic that subtle shifts often go unnoticed. But it’s actually a team sport for your brain: cortex (planning), basal ganglia (automaticity), cerebellum (timing), and brainstem/spinal circuits (rhythm). They all contribute to smooth, coordinated movement Dysfunction in any of these areas can cause stiffness, slowness, or slight instability which may at first be dismissed as normal aging.

Gait micro-instabilities can look like:

Walking at a slower pace

Reduced arm swing

Slower turns or making a slight hesitation on turns

Struggling with a dual-task gait (such walking while counting)

You might not notice these changes in yourself, but others may point them out. If a loved one mentions that your gait seems different, pay attention. Subtle walking changes can be an early sign of neurodegeneration, but they can also have other causes like arthritis, inner ear problems, or medication side effects. If walking changes persist or worsen, discuss them with your doctor to determine the underlying cause.

A loss of get-up-and-go is a common early sign in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and frontotemporal dementia that is often missed. [24] Apathy is about motivation circuits, not sadness The anterior cingulate cortex and mesolimbic dopamine pathways help you initiate and persist When these networks under-fire, starting activities feels heavy even if your mood is neutral. That’s why apathy can precede depression or occur without it in several dementias.

This may look like depression without the sadness, such as:

Losing interest in hobbies or feeling "blah" about things you used to enjoy

Feel indifferent and disengaged without necessarily feeling sad

No motivation to start of continue activities (even simple ones like getting dressed or making a phone call

Not wanting to engage in social interactions

It’s not laziness; the “ go ” signal is faint Apathy is often more apparent to family and friends than to the person experiencing it. If loved ones express concern about your lack of interest or initiative, take it seriously. Apathy can be a sign of underlying brain changes, but it can also be caused by sleep problems, stress, or certain medications. A thorough medical evaluation can help pinpoint the cause and guide treatment.

If you ' ve been bumping into furniture, missing the cup when pouring coffee, or having close calls in the car, it could indicate your brain's judgment of space is slightly off This can be an early occurrence in Alzheimer's or dementia with Lewy bodies. [25]

Navigating spaces relies on the parietal lobes of the brain, which integrate vision, touch, and positional information. Degeneration in this region can cause misjudgments of distance or trouble coordinating movements with what you see.

Misjudging spaces and distances can look like:

Clipping doorframes when walking through

Misjudging the height of steps and stumbling

Trouble parking straight or within the lines

Getting turned around in familiar places

Overshooting a cup when pouring

Difficulty lining up keys with a lock

Needing more light/contrast to navigate at dusk

Spatial misjudgments can be unsettling, especially if they're a change from your usual abilities They can also be dangerous if they lead to falls or accidents

It's important to note that occasional clumsiness or misjudgments are normal, especially when you ' re tired, distracted, or in a new environment. Spatial skills can also decline with normal aging, particularly in adults over 70. [26]

But if you find yourself consistently bumping into things, tripping, or getting disoriented or spatial problems appear suddenly or progress rapidly it could be an early warning sign of neurological change

Your brain plays a significant role in regulating automatic functions, such as blood pressure, bladder control, and bowel movements. When people notice new issues like dizziness upon standing, constipation, or frequent urges to urinate, they often don't connect them to brain health But these changes can precede cognitive decline, especially in conditions like Parkinson's, Lewy body dementia, and multiple system atrophy, where autonomic nervous system function is impacted early on. [27]

This happens because the brainstem and limbic areas that control these basic body functions are some of the first to accumulate abnormal proteins, causing autonomic dysfunction before thinking skills decline.

Other body function changes to be on the lookout for can include:

Becoming light-headed on standing

Constipation or urinary urgency

Body temperature swings

Sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction or changes in libido

Excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis) or lack of sweating (anhidrosis)

Because these symptoms are also common in other conditions like heart disease, digestive disorders, hormonal changes, or anxiety, it's important not to jump to conclusions. However, if autonomic symptoms appear along with other signs on this list, they could indicate an underlying neurological issue.

If you or someone you know have noticed any of the subtle signs covered in Chapter 2, your next step is to discuss them with a doctor.

It can feel intimidating to bring up brain health concerns, but remember – early detection is key to getting the support you need.

You're being proactive, not paranoid. In this case, it’s better to know than not know.

When you mention your symptoms, your doctor will likely ask detailed questions and may perform some simple in-office assessments.

If they suspect a potential issue, they may refer you to a specialist for more comprehensive testing.

Let's go through how a doctor might evaluate each of the 10 signs.

The clinician will be looking for reduced ability to identify common odors vs a simple nasal blockage. They will usually try to first rule out recent cold/allergies, chronic sinusitis, COVID-related loss, smoking/vaping, meds that dry out nasal passages.

Your doctor may use a "scratch-and-sniff" test like the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT). You'll be asked to identify a series of common odors (such as coffee, flowers, mint). Difficulty naming smells, even if you can detect them, can be an early clue of brain changes

A clinician looks for shrinking letter size across a line, cramped spacing, smaller/fainter strokes, tremor spillover (tiny, rhythmic shakes from a hand tremor that “spill” into your writing showing up as wavy lines, jittery edges, or a saw-tooth look on letters and spirals) They will try to first rule out arthritis, hand pain, neuropathy, poor lighting, or new vision issues.

Tool: Handwriting Analysis

You may be asked to provide a handwriting sample, like copying a sentence or drawing spirals and loops The doctor will assess the size, spacing, and consistency of your writing. Sometimes, they’ll compare it to older samples (like a signature from years ago) to see if it’s gotten smaller or shakier.

The clinician is evaluating how your face moves They’ll watch for spontaneous vs prompted facial movement (do you emote naturally during conversation), blink rate, symmetry of smile and eyebrow raise, depth of the nasolabial folds, and voice qualities such as reduced volume/monotone (hypophonia) They try to first rule out depression/fatigue, sedating meds, or social masking, where a person suppresses facial cues out of habit or context (e.g., “neutral work face,” shyness, cultural norms), making expression look flatter even without a movement problem.

Tool: Clinical Observation or Facial Expression Assessment

The doctor will watch your face during a conversation to see if you ’ re showing emotions like smiling or frowning. They’re likely to note any asymmetry or reduced expressiveness You may be asked to mimic expressions (like raising your eyebrows) Some specialists use video analysis or electromyography (EMG) to measure facial muscle activity

Because sleep disruptions can be caused by many things, the clinician will be looking for specific signs related to neuro disorders such as REM sleep behavior disorder (acting out dreams), excessive daytime sleepiness, or fragmented sleep that affects daytime cognition. They’ll aim to first rule out late caffeine/alcohol, shift work, meds that disturb sleep, or other non-neurologic related sleep conditions

Your doctor may have you or a partner complete a questionnaire about your sleep habits and any unusual nocturnal behaviors, such as talking or kicking in your sleep. They may ask you to keep a sleep diary logging your sleep-wake times, awakenings, and daytime drowsiness. An overnight sleep study (polysomnography) may be ordered to assess for conditions like REM sleep behavior disorder. You’ll sleep in a lab with sensors to track brain waves, movements, and breathing, which can reveal REM sleep without normal muscle atonia (the temporary, natural paralysis or loss of muscle tone that occurs during REM), abnormal movements/vocalizations during REM, apneas/hypopneas with oxygen drops, and disrupted sleep architecture (the pattern and sequence of different sleep stages throughout the night).

Vision problems can be caused by many things. So with this evaluation, a clinician is looking to rule out issues such as cataracts, macular disease, dry eye, outdated glasses/contact prescription, and glare/poor lighting, which can affect color perception. They'll be paying attention to blue–yellow mix-ups, reduced contrast sensitivity, and slower color identification under normal light Difficulty distinguishing shades, especially blues and greens, can indicate early changes in the visual system.

Tool: Color Vision Test

Doctors might use a test like the Ishihara Color Test, where you look at plates with colored dots to identify numbers or patterns Another option is the FarnsworthMunsell 100 hue test, where you will arrange colored discs in order to see if you ’ re mixing up similar colors, like blue and green.

Being disorganized or impulsive doesn’t necessarily equal neurodegeneration. Other conditions such as ADHD, traumatic brain injury, or substance abuse can also lead to disorganization or impulsive choices. Even things like sleep deprivation, high stress, thyroid/B12 issues, sedating or anticholinergic meds {like some antihistamines or bladder meds}, or depression/anxiety can all affect mental clarity and self-control So when evaluating for a neuro condition, the clinician is looking for slower taskshifting, more errors under distraction, and trouble holding steps in mind.

Your doctor may administer brief cognitive tests that assess planning, problemsolving, mental flexibility and inhibitory control. Examples include the Trail Making Test (connecting dots in order), Stroop Test (where you name the color of a word, not the word itself), or verbal fluency tasks (listing words starting with a given letter). These tests assess how well you plan, focus, or switch tasks, which can indicate early brain changes

As walking changes can be very subtle, the clinician is looking for slower pace, reduced arm swing (often one-sided), cautious or slower turns, or instability when multitasking. They’ll seek to first rule out joint pain, poor footwear, low blood pressure/dehydration, vestibular issues, sedating medications, which can all affect gait and balance

You may be asked to walk across the room while the doctor observes your gait, looking for slight asymmetry, reduced arm swing, shuffling steps or hesitation on turns They could use a “Timed Up and Go” test, where where they time how long it takes you to stand up from a chair, walk 20 feet, and sit back down. Comparing this to age-matched norms can reveal subtle slowness. More sophisticated gait analysis may involve video recording or pressure-sensitive walking mats.

For this sign, a clinician is looking to rule out depression, sleep problems, pain, endocrine/nutrient issues (thyroid, B12), social isolation, or medication effects, all of which can cause apathy-like symptoms. They’re looking for reduced initiation and persistence despite neutral mood, and a decline in goal-directed behavior.

Tools: Apathy Scales, PHQ-9, Clinical Interview

Your doctor may ask you or a family member to complete the Apathy Evaluation Scale, a questionnaire assessing your motivation and interest in daily activities or socializing. You may be asked to take the PHQ-9, a self-report questionnaire consisting of nine questions that assess the frequency and severity of depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. TThey may also use caregiver input to compare "then vs. now " for daily drive and follow-through, as well as talk to you to rule out depression and see if it's really apathy, which feels more like indifference than sadness or hopelessness.

The clinician will be looking for issues like misjudging distances between objects, difficulty aligning edges or corners, or trouble with organizing objects in space, especially under time pressure. They'll try to first rule out vision problems (cataracts, outdated prescription), poor lighting/glare, or peripheral neuropathy affecting sensation in the feet Addressing visuospatial difficulties is crucial because many common, but potentially dangerous, activities, such as driving, walking, or using tools, rely on accurate depth perception and spatial awareness.

You may be given tests of spatial perception and construction, such as the Clock Drawing Test (drawing a clock face with numbers and hands set to a given time) or the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (copying a complex line drawing, such as overlapping pentagons). Difficulty with spatial relationships and 3D perspective can be early signs of decline in parietal lobe function.

Body function changes such as dizziness, constipation, urinary urgency, or abnormal sweating can have many root causes So they'll be looking to rule out dehydration, anemia, low blood sugar, GI disorders, perimenopause, medication side effects, or anxiety, which can cause many of the same symptoms as autonomic dysfunction related to neurodegeneration

Tools: Autonomic Testing, Symptom Questionnaires

If you ' ve had dizziness on standing, your doctor may conduct an orthostatic test. This is where they measure your blood pressure and heart rate lying down, immediately upon standing, and after 2-3 minutes of standing to assess for orthostatic hypotension. You may fill out questionnaires about experiences like constipation, urinary urgency, sexual dysfunction or abnormal sweating. Referral to a specialist for more detailed autonomic testing may be needed.

Brain scans

MRI or CT imaging can reveal structural changes, evidence of stroke or tumor, or patterns of atrophy associated with specific dementias.

Neuropsychological tests

Pen-and-paper or computer tests that dive deeper into your memory, language, problem-solving, and visual-spatial skills. These help clarify your cognitive strengths and weaknesses

Lab tests

Blood work to check for infections, vitamin deficiencies, thyroid dysfunction, or other medical conditions that can impact brain function Genetic tests for familial dementias may also be recommended.

Functional brain imaging

fMRI or PET scans that track brain activity during mental tasks to detect areas of dysfunction not visible on structural scans.

In some cases, these invasive tests may be suggested to measure amyloid, tau, or other Alzheimer’s-related proteins in the brain or cerebrospinal fluid.

Remember, these assessments aren't meant to label you, but to identify areas where your brain may need support. Evaluation is the first step in proactive care.

In addition to medical tests, your doctor may recommend lifestyle changes and interventions tailored to your specific concerns.

In the next chapter, we'll explore proactive steps you can start taking now to give your brain an extra boost Early action, combined with medical partnership, puts you in the driver's seat of your cognitive health.

While the early signs of potential brain changes can feel worrisome, there's a lot you can do to support your cognitive health.

The strategies in this chapter are backed by research and focus on lifestyle, diet, and gentle practices to nourish your neurons.

While they won't cure serious conditions, they can improve brain function and build resilience.

Even small shifts, applied consistently, can make a meaningful difference in how you think and feel

It's never too early or too late to start giving your brain the support it needs to thrive.

Eat antioxidant-rich foods like blueberries, spinach, and walnuts These protect brain cells from damaging inflammation and oxidative stress. Omega-3 fatty acids from fish or flaxseed also support the olfactory system.

Practice smell training by intentionally sniffing essential oils like lemon, clove, rose, and eucalyptus for 20 seconds each, twice a day. Studies show this can enhance olfactory function and encourage neuroplasticity, possibly by stimulating the regeneration of smell receptors. [28]

Clean up your environment. Reduce indoor smoke/fragrance overload; humidify dry rooms; treat nasal allergies as advised.

Grab a few jars of spices from your kitchen, like cinnamon, cumin, and oregano. Close your eyes, take a whiff of each one, and see how many you can identify by smell alone.

Make it a daily game to challenge and strengthen your olfactory circuits.

Focus on aerobic activity + strength Movement boosts dopamine signaling and motor automaticity. Target 150–300 minutes/week of moderate activity plus 2 strength sessions; include posture and shoulder mobility to free arm swing.

Engage in activities that emphasize fluid, relaxed movement, and mind-body coordination, such as tai chi, yoga, and dance. Aim for 30 minutes most days to improve blood flow to the brain regions that control fine motor skills.

Practice hand exercises like squeezing a stress ball, molding putty, or tracing large shapes and letters. Writing on a slant board or angled surface may also help. These build hand strength and dexterity, and precision drills reinforce cortical–basal ganglia loops used in writing

Incorporate "air writing" into your daily routine.

While waiting in line or listening to a podcast, trace cursive letters or shapes in the air with your index finger.

Use fluid, expansive movements that engage your whole arm.

This anywhere activity helps maintain writing motor pathways without pen and paper, and the broad motions can counteract micrographia's smallness.

Perform facial exercises like wide smiles, eyebrow raises, puckered lips, and cheek puffs 10 times each, twice daily. This keeps facial muscles active and neural pathways engaged. Adding resistance by pressing fingers against your face can increase the challenge

Try Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT). This is a specialized therapy originally developed for Parkinson's patients to improve vocal loudness and expression. The principles of exaggerated, high-effort movements can be adapted to facial exercises to counter hypomimia [29]

Stay socially engaged through face-to-face conversations, laughter with friends, and expressive activities like singing or acting Social interaction naturally elicits facial expressions, boosts activity in the prefrontal cortex (associated with emotion), and exercises the brain circuits involved in emotional communication

Do a “big face” circuit:

10 reps each of an eyebrow raise, wide smile, cheek puff, lip pucker; hold each for 3 seconds. 3 circuits.

High-amplitude reps retrain speed and size of facial movements, reinforcing motor pathways.

Maintain a consistent sleep schedule, aiming for 7-9 hours per night. Limit screen time and create a wind-down routine 1-2 hours before bed. Keep your bedroom dark, quiet, and cool (60-67°F) to support your natural circadian rhythms.

Add relaxation practices to your daily routine. Try meditation, deep breathing, or a warm bath with lavender oil to calm your nervous system. These lower arousal, help you fall asleep faster, and reduce overnight awakenings

Try vagal stimulation The vagus nerve is a key regulator of the parasympathetic nervous system, which controls your body's "rest and digest" functions. Vagal stimulation enhances parasympathetic tone, improving sleep architecture and brain repair There are many vagal stimulation exercises you can try You can do diaphragmatic breathing (5–10 minutes daily), gargling or humming for 2-3 minutes per day, or use non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation devices to modulate brainstem sleep centers.

Practice progressive muscle relaxation. Starting at the feet, gently tense for 5 seconds then release for 10 seconds, moving body part by body part up to the face. It should take you about 8–10 minutes. This kind of systematic release reduces body/mind tension and eases nighttime restlessness.

Eat plenty of leafy greens, orange peppers, and sweet potatoes, which are rich in lutein and zeaxanthin – antioxidants that accumulate in the retina and brain. These nutrients protect color-sensing cells from damage. [30]

Challenge your visual processing with puzzles, color-by-number pages, spot-thedifference puzzles, and color-matching games. Intentionally focusing on color distinctions keeps those neural networks active Practice for 10-15 minutes to enhance neuroplasticity.

Light your tasks. Use bright, even task lighting right where you work (desk, kitchen counter), reduce glare with matte bulbs/shades, keep light color temperature consistent, and add high-contrast tape on stair edges or shelf lips so boundaries “ pop. ” Lighting and contrast reduce processing load so color differences are easier to spot.

Do a daily color sort:

Cut 12 blue-to-green swatches from magazines and arrange most-blue → most-green, then reverse (3 minutes).

Repeated near-hue discrimination sharpens color-processing circuits.

Play games that target planning, problem-solving, and mental flexibility, such as chess, Scrabble, or Lumosity brain training. Aim for 15-20 minutes per day to strengthen frontal lobe functions.

Incorporate focused work sessions into your day. Work 10–15 minutes on a single task, take a 2–5 minute reset, then repeat. Gradually extend the work block as it gets easier This cuts context-switching “brain tax” and strengthens sustained attention, working memory, and prefrontal control.

Practice mindfulness meditation to enhance attention control and reduce stressrelated impulsivity. Start with 5-10 minutes of focused breathing each day, gradually increasing as you build the habit

Choose one area of your life to declutter and organize, whether it's your desk, your email inbox, or your kitchen pantry.

Use a notebook, app, or calendar to break the project into small, manageable steps.

Offloading information into external systems and reducing clutter can lighten the load on your prefrontal cortex, making it easier to stay organized and make decisions.

Incorporate balance exercises into your daily routine, such as standing on one foot while brushing your teeth, walking heel-to-toe, or practicing tai chi. These enhance communication between your brain and body for stable movement.

Engage in aerobic exercise like brisk walking, swimming, or cycling for 30 minutes, 5 times per week. Cardio boosts cerebral blood flow and supports the brain regions involved in motor control and coordination Strength training 2-3 times per week can also improve muscle activation and gait stability.

Challenge your gait with supervised dual-task practice. Try walking while talking, counting backward, or carrying an object. Start in a safe environment with a partner, and keep the secondary task brief and simple Gradually increase the complexity over time. This type of practice helps rebuild the automaticity of walking, which can be disrupted in early neurological changes.

Incorporate "sit-to-stands" into your daily routine.

Each time you stand up from a seated position, focus on using your leg muscles to rise smoothly to a full stand, with minimal use of your hands.

Pause briefly, then lower yourself back down slowly, maintaining control. Repeat this 5 times.

This simple exercise strengthens the leg muscles that support stable walking and challenges balance and coordination.

Set small, achievable goals each day, like making your bed, calling a friend, or trying a new recipe. Checking off these wins activates your brain's reward system and builds motivation momentum. Celebrate each accomplishment!

Start each morning with an " energy spark." Get 5–10 minutes of outdoor light and a short walk before any screen time. Morning light helps reset your circadian rhythm, which influences motivation and mood, and physical activity boosts dopamine and norepinephrine, neurotransmitters that drive goal-directed behavior.

Volunteer for a cause you care about or take on a new hobby that energizes you. Having a sense of meaning and mastery can reignite your zest for life. Social connection is also a powerful antidote to apathy

Support your dopamine system with targeted nutrition. Include foods or supplements rich in L-tyrosine (500–1000 mg/day, under supervision) and vitamin D (1000–2000 IU/day) to support dopamine and mood regulation.

Set a 5-minute “values starter.”

Pick one tiny action that matters (water plants, text a friend, chop veggies), start a 5-minute timer, and begin.

Quick wins trigger the brain’s reward circuits and lower the activation barrier for the next step.

Upgrade visibility. Declutter walk paths, add nightlights in halls/baths, and place high-contrast edge tape on stairs/rug borders. A visually clear and well-lit space reduces the cognitive load on your brain's spatial processing centers, making it easier to judge distances and avoid obstacles

Challenge your spatial skills with jigsaw puzzles, Lego building, or 3D video games Manipulating objects and navigating environments exercises your parietal lobe, which processes spatial information.

Incorporate vision-protecting nutrients into your diet, like vitamin A from sweet potatoes, vitamin C from citrus, vitamin E from sunflower seeds, zinc from pumpkin seeds, and omega-3s from flax, chia, or walnuts These help maintain eye health and visual processing pathways in the brain. Avocados, nuts, or olive oil provide fats that support brain cell health and communication.

Set up an obstacle course in your living room using pillows, chairs, or boxes.

Navigate the course forward and backward, with and without shoes, and at different speeds.

This practice helps engage your brain's spatial processing networks and can highlight areas where you might need extra support or adaptations in your daily environment.

Practice deep belly breathing for 5-10 minutes a day, focusing on expanding your abdomen on the inhale and gently contracting it on the exhale. This vagal nerve stimulation can help regulate heart rate, blood pressure, and digestion.

Stay well hydrated and eat a fiber-rich diet with plenty of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes. This supports healthy bowel movements and blood pressure balance Limit caffeine and alcohol, which can exacerbate autonomic symptoms.

Incorporate gentle movement practices like yoga, tai chi, or stretching into your daily routine. These activities help calm your nervous system, improve body awareness, and support functions like bladder control and blood pressure regulation.

Sit or lie down in a quiet, comfortable space and place one hand on your chest and the other on your belly.

Take a slow, deep breath in through your nose, focusing on expanding your belly like a balloon. Exhale slowly through pursed lips, feeling your belly fall. Repeat this belly breathing for 5-10 breaths.

This simple exercise helps strengthen your vagal tone, which is key for regulating autonomic functions like heart rate, digestion, and blood pressure.

The human brain has a remarkable capacity to forge new neural pathways and adapt to challenges.

By identifying early warning signs, having open conversations with health professionals, and committing to nourishing your neurons, you are putting yourself in the best possible position to preserve your memories, personality, and independence

Small daily choices add up over a lifetime.

By filling your plate wisely, staying mentally and physically active, and prioritizing sleep and stress relief, you ' re giving your brain the support it needs to stay sharp and healthy for years to come.

And don’t forget, brain-healthy habits are not all-or-nothing Progress, not perfection, is what counts. Start wherever you are and trust that your efforts will add up.

Your incredible, neuroplastic brain is so worth nurturing!

Jason Prall is a former mechanical engineer turned educator, health practitioner, speaker & filmmaker.

Due to 20 years of his own health challenges, Jason discovered the reality behind his symptoms. Through this process, he began working remotely with individuals around the world to provide solutions for those suffering from complex health issues that their doctors were unable to resolve

In 2016, Jason transitioned from working in the integrative disease-care model of health optimization & lifestyle medicine.

These lessons culminated in the documentary film series The Human Longevity Project, which uncovers the complex mechanisms of chronic disease & aging & the true nature of longevity in our modern world

Jason Is also the author of the critically acclaimed book, “Beyond Longevity: A Proven Plan for Healing Faster, Feeling Better & Thriving at Any Age.”

You can reach Jason at Info@AwakenedCollective.com.

[1] Caselli, R J , Langlais, B T , Dueck, A C , Chen, Y , Su, Y , Locke, D E C , Woodruff, B K , & Reiman, E M (2019) Neuropsychological decline up to 20 years before incident mild cognitive impairment Alzheimer S & Dementia, 16(3), 512–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.09.085

[2] Alzheimer’s Disease facts and figures (n d ) Alzheimer’s Association https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

[3] Mendez M F (2019) Early-Onset Alzheimer Disease and Its Variants Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn ), 25(1), 34--51 https://doi org/10 1212/CON 0000000000000687

[4] Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease | Alzheimer’s Disease and Aging | OHSU (n d ) https://www ohsu edu/brain-institute/understanding-alzheimers-disease

[5] theaftd.org. (2021). Partners in FTD care. In Partners in FTD Care [Newsletter]. https://www theaftd org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/PinFTDcare summer 2021 pdf

[6] Alzheimer’s Disease facts and figures. (n.d.). Alzheimer’s Association. https://www alz org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

[7] Franchina, P. (2023, July 13). New Study Indicates that New Cases of Parkinson’s Disease are 50% Higher than Past Estimates American Parkinson Disease Association https://www apdaparkinson org/article/new-study-indicates-parkinsons-disease-is-50-moreprevalent-than-previously-thought/

[8] Fernandes, C (2021, August 16) About LBD Lewy Body Dementia Association https://www lbda org/about-lbd/

[9] U S life expectancy (1950-2025) (n d ) https://www macrotrends net/globalmetrics/countries/usa/united-states/life-expectancy

[10] Nabi, M., & Tabassum, N. (2022). Role of environmental toxicants on neurodegenerative disorders. Frontiers in Toxicology, 4 https://doi org/10 3389/ftox 2022 837579

[11] Shlomi-Loubaton, S., Nitzan, K., Rivkin-Natan, M., Sabbah, S., Toledano, R., Franko, M., Bentulila, Z., David, D , Frenkel, D , & Doron, R (2025) Chronic stress leads to earlier cognitive decline in an Alzheimer’s mouse model: The role of neuroinflammation and TrkB Brain Behavior and Immunity https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2025.03.021

[12] Dunn, A R , O’Connell, K M , & Kaczorowski, C C (2019) Gene-by-environment interactions in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 103, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.018

[13] Rasmussen, J., & Langerman, H. (2019). Alzheimer's Disease - Why We Need Early Diagnosis. Degenerative neurological and neuromuscular disease, 9, 123--130. https://doi org/10 2147/DNND S228939

[14] Devanand, D. P., Lee, S., Manly, J., Andrews, H., Schupf, N., Doty, R. L., Stern, Y., Zahodne, L. B., Louis, E. D., & Mayeux, R. (2015). Olfactory deficits predict cognitive decline and Alzheimer dementia in an urban community Neurology, 84(2), 182–189 https://doi org/10 1212/WNL 0000000000001132

[15] Attems, J., Walker, L., & Jellinger, K. A. (2014). Olfactory bulb involvement in neurodegenerative diseases Acta Neuropathologica, 127(4), 459–475 https://doi org/10 1007/s00401-014-1261-7

[16] De Stefano, C., Fontanella, F., Impedovo, D., Pirlo, G., & Di Freca, A. S. (2018). Handwriting analysis to support neurodegenerative diseases diagnosis: A review Pattern Recognition Letters, 121, 37–45 https://doi org/10 1016/j patrec 2018 05 013

[17] Facial masking. (n.d.). Parkinson’s Foundation. https://www.parkinson.org/understandingparkinsons/movement-symptoms/facial-masking

[18] Howell, M. J., & Schenck, C. H. (2015). Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder and Neurodegenerative Disease JAMA Neurology, 72(6), 707–712 https://doi org/10 1001/jamaneurol 2014 4563

[19] Musiek, E. S., & Holtzman, D. M. (2016). Mechanisms linking circadian clocks, sleep, and neurodegeneration Science (New York, N Y ), 354(6315), 1004–1008 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah4968

[20] Gjerstad, M D , Tysnes, O B , & Larsen, J P (2011) Increased risk of leg motor restlessness but not RLS in early Parkinson disease Neurology, 77(22), 1941--1946 https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823a0cc8

[21] Otaiku, A I (2022) Distressing dreams and risk of Parkinson’s disease: A population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine, 48, 101474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101474

[22] Ercolano, E , Bencivenga, L , Palaia, M E , Carbone, G , Scognamiglio, F , Rengo, G , & Femminella, G D (2023) Intricate relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and dementia in older adults. GeroScience, 46(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00958-4

[23] Kim, H J , Ryou, J H , Choi, K T , Kim, S M , Kim, J T , & Han, D H (2022) Deficits in color detection in patients with Alzheimer disease. PLoS ONE, 17(1), e0262226. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262226

[24] Lanctôt, K. L., Agüera-Ortiz, L., Brodaty, H., Francis, P. T., Geda, Y. E., Ismail, Z., Marshall, G. A., Mortby, M. E., Onyike, C. U., Padala, P. R., Politis, A. M., Rosenberg, P. B., Siegel, E., Sultzer, D. L., & Abraham, E H (2017) Apathy associated with neurocognitive disorders: Recent progress and future directions Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association, 13(1), 84–100 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.05.008

[25] Devenyi, R A , & Hamedani, A G (2024) Visual dysfunction in dementia with Lewy bodies Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 24(8), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-02401349-8

[26] Tragantzopoulou, P , & Giannouli, V (2024) Spatial Orientation Assessment in the Elderly: A Comprehensive Review of Current tests. Brain Sciences, 14(9), 898. https://doi org/10 3390/brainsci14090898

[27] Palma, J. A., & Kaufmann, H. (2018). Treatment of autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson disease and other synucleinopathies. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 33(3), 372–390 https://doi org/10 1002/mds 27344

[28] Kim, B., Park, J. Y., Kim, E. J., Kim, B. G., Kim, S. W., & Kim, S. W. (2019). The neuroplastic effect of olfactory training to the recovery of olfactory system in mouse model International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology, 9(7), 715–723 https://doi org/10 1002/alr 22320

[29] Saffarian, A., Shavaki, Y. A., Shahidi, G. A., Hadavi, S., & Jafari, Z. (2019). Lee Silverman voice treatment (LSVT) mitigates voice difficulties in mild Parkinson’s disease PubMed, 33, 5 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6504915/

[30] Johnson, E J (2012) A possible role for lutein and zeaxanthin in cognitive function in the elderly American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 96(5), 1161S-1165S https://doi org/10 3945/ajcn 112 034611