by IOANA A. RACU, ‘24

by IOANA A. RACU, ‘24

Dr. Daniel Coslett joined Drexel as an assistant professor of architectural history in the Department of Architecture, Design & Urbanism in the Westphal College of Media Arts & Design in 2022. Professor Coslett relocated to Philadelphia, his hometown, after teaching at Western Washington University in the Department of Art & Art History. He received his PhD from the University of Washington in Seattle, where he also taught, offering courses on architectural history and theory, global built environments, and historic preservation for the Departments of Architecture and Urban Design and Planning, both in its College of Built Environments. always wanted to be a professor. My grandfather was a very well-read person who loved history and was always reading. To this day, can see him sitting with a stack of library books next to his chair in the den at my grandparents’ house.

My grandfather studied history in school, and my grandmother also studied history in school. My mother was very interested in history, and much of my childhood was spent coming into the city. I grew up just in the suburbs, out in Delaware County. would come to the city with my grandparents. We would go to museums, and we would go with my mother to battlefields and historic sites all over the country. It was always about being out there and surrounded by history. Ever since then, I always thought that being a professor is what I want to do. I like learning, and like sharing. enjoy being around people who are enthusiastic about all of this stuff. It just was never a question for me.

I always wanted to be a professor. My grandfather was a very well-read person who loved history and was always reading. To this day, I can see him sitting with a stack of library books next to his chair in the den at my grandparents’ house.

I was going to keep studying archaeology and teach classics, Latin, and Greek, which I did in college. Then I lived in North Africa, for about a year on a Fulbright Scholarship. I got really interested in what was happening there. I was living in Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, and I was wondering: ‘What are these buildings? How were these buildings built? Why do things seem so “French” here? What does all this mean?’ So one thing led to the next and just started looking into architecture. I wanted to do a degree in the history of architecture, and then go to design school, but then I got really into history, so stuck with it.

In Tunis, Professor Coslett experienced the effects of French colonialism in North Africa. This influenced a major shift in his academic interests and career expectations overall.

The time I spent living in North Africa really changed the way I thought about things because being around them and seeing them really changed my understanding of architecture and built environments. That’s what pushed me into the realm of architecture and art history. wouldn’t say I fell into it because it was always there. But it was a natural progression.

At Drexel, teach most of the required architectural history survey courses for our architecture undergrads, for our interior design majors, and then for many of our architectural engineering students. I also teach an elective for non-majors that focuses on historic architecture in Philadelphia and around the world. created this one for Drexel students because we have so much amazing architecture in our city. Most of the classes I teach here are required classes, though, which sets up a different dynamic and can come with challenges.

The time I spent living in North Africa really changed the way I thought about things because being around them and seeing them really changed my understanding of architecture and built environments.

Lecture classes are a big challenge for teachers, but Professor Coslett produces engaging material and exercises to keep students’ on track.

My courses are primarily lecture courses. So I have to take a lot of historical material and package it for students in a way that makes sense for them that they can see as relevant in their design work, whether students of architecture, interior design, or engineering. That is a pretty big challenge because for people who are studying architectural engineering, for example, learning about ancient pyramids may be fun, but they don’t necessarily see it as relevant. To counter that, I try to make them engaging, relevant and pleasant, but also try to make them more interactive and dynamic. It used to be that professors would come in and stand there and just deliver a full lecture, the students would just sit there and then leave. I try to avoid doing that as much as I can, but it’s inevitable in the large lecture classes.

History can very easily be dull, but it can become quite fascinating if taught from the right angle. It is all about relating the content to the students’ curiosities to keep the topics approachable.

I present material from the past 5,000 or so years around the globe. We start with a window of time, bounce around the world a bit, and then leap forward in time, move around again, and then move forward yet again, and again. The passing of time is ultimately the constant in the courses. I constantly remind the students that if they were taking architecture classes in the 19th century, right, if this was 1830 France, they would come to their architectural history classes, and they would be introduced to historical examples, which they would effectively be asked to copy. That is not the way architecture is anymore. The point of my classes is not to provide precedents that people will then just copy. It’s about getting them to see more clearly, to ask questions, and to think differently about accumulated history.

If people don’t understand those histories, they won’t get the buildings. Does this building force you to move in a certain way? What does that make you think? If the building has a lot of steps that you go up, then do you get tired out by going up those steps? I want people to take away those bigger questions about lighting, body and movement, thinking and responses that are timeless. What I try to encourage people to develop in my classes is to develop what I would call “Built Environments Literacy,” that is the ability to “read” the buildings and spaces around us.

Students ask: “So why does it matter what this church from 800 years ago looks like?” When we’re talking about a Gothic cathedral, we’re talking about space, we’re talking about light, we’re talking about color and materials. When you’re sitting down to think about a building that you’re designing or an interior space that you’re furnishing, or designing, you have to think about where the windows are and how the orientation of the building matters. Does the sun come up? Does it shine through those windows? What are those windows made out of? Are they colored? Are they a certain shape? Does that mean that the light falls on the floor in a certain way? Does that make people feel a certain way?

Being able to walk around in Philadelphia, down Market Street, and say “I see a building right there. I don’t know who the architect is. don’t know what year it was built. don’t know anything about its particular history. But I can understand it a little bit. I understand why it looks that way, or what those materials tell us, or where they came from. I can understand why someone building a church in West Philadelphia would make it look like that, or a library in Center City would look like that. It’s about the relevance of looking, of seeing more than individual buildings just standing there.

History is about the entire world’s history, yet history textbooks have taught us otherwise. Historians, including Professor Coslett, are trying to change the Eurocentric narrative and go fully global with their approach.

Traditionally, teaching architecture and architectural history has been a very Eurocentric, Western-centric field, and approach. It used to be that scholars of architecture in architectural history assumed that the only buildings that mattered were the big, fancy European buildings.

Content is one big part of this—how much of, and from where, do you put the material you cover?

That is not the way people who take architectural history seriously want to teach it now, because that way leaves out so much. It suggests that there are only some places that are important, and only some forms of architecture—churches, palaces, government buildings—that are the things that matter. It’s of course impossible to cover everything, but when we teach these classes now, we try to be global. This often means adding more material. But we have limited time, so we have to cut some material out to make space. So it’s about the content, but it’s also about the process or the means of delivery, right? Simply adding more material is one approach, sure. That doesn’t really solve all the problems though, plus you only have so much time, so you

can’t just keep adding more and more, so you have to cut some things out or at least spend less time talking about some of the canonical buildings. So then the question is, what do you skip? Content is one big part of this—how much of, and from where, do you put the material you cover? It’s not just about content, but it’s about the narrative too. It’s not just about adding more, but it’s about trying not to perpetuate myths that suggest that the Renaissance was perfect, and that Greece is where everything comes from, or that idealized eras were immune to issues of race and classism, and misogyny.

I had a student come to me last week, because we covered Gothic cathedrals on Tuesday, and on Thursday we looked at mud brick mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa. The student said, “It’s really weird to be looking at gigantic cathedrals in France, and then to be looking at mosques in Africa back to back. Why did we do that that way?” said, “Well, remember, it’s happening at the same time; we see things this way here because of the chronology. I’m not saying that one is better than the other, one is more important than the other or one people are more valuable than the other. It’s just the time. This is what’s happening in France. This is what’s happening in Mali, and this is what’s happening in China, in India….”

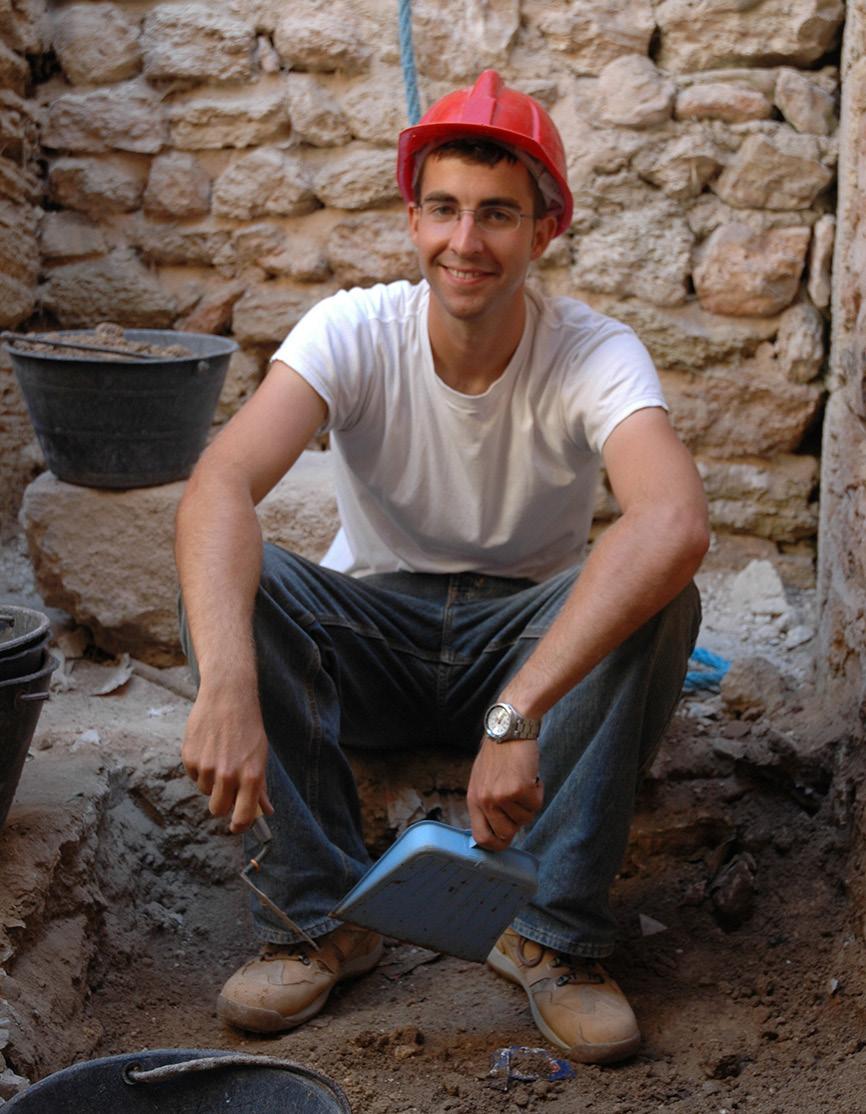

[Photo by Eva Krewson]

I’m not saying that one is better than the other, one is more important than the other or one people are more valuable than the other. It’s just the time. This is what’s happening in France. This is what’s happening in Mali, and this is what’s happening in China, in India….”

Buildings are never built inside a vacuum. The history behind some of the most beautiful buildings around us is marked with violence and complexity. Students need to know about this! Professor Coslett makes himself accessible, both through his use of language and his use of time.

try not to perpetuate master narratives that overlook a lot of things, or leave a lot of people out. When we teach about colonial American architecture from the 18th century, we have to talk about slavery. We have to talk about outbuildings that are part of larger built environments, so that people are aware and understand that Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, is much more than an impressive building. It was a place that housed enslaved people and was very violent in a lot of ways. In the past, people might have overlooked that and not mentioned those kinds of things. But now it’s about being more honest, as much as we can, and bringing that material forward to people. So it’s not just adding more geography, but it’s saying different things about some of the same buildings, in an effort to provoke more complete thinking and open people’s eyes to things that might have been marginalized.

I have regular weekly posted office hours. I think making myself regularly available and accessible is a big part of teaching better. I try to coordinate with the other professors who are teaching studio classes, at least within architecture, to make sure that my testing doesn’t conflict with their big studio reviews so that people have the space and time to dedicate to my courses and to their other ones. That type of coordination is very important and often gets overlooked. You have students who have a paper the night before, they have a 12-hour review the day after they had a big studio project and then everyone’s just overwhelmed and can’t do anything. Also, as someone who’s spent a lot of time in grad school and can often use big words that are unnecessary and I try to remind myself that I don’t need to do that so much. It’s just about presenting the material in a way that makes sense and bringing people along.

History, in the academic context, has been slow to change, but has made good progress in recent years. Professors are making immense efforts to introduce students to wider perspectives on the world and to address challenging history. At Drexel, Professor Coslett uses lectures as an opportunity to provide accurate and strong informational foundations for students in Westphal, all while emphasizing the global diversity of historic built environments and their relevance in his educational strategy. It’s a work in progress.

Community & Global Initiatives

Dean Jason Schupbach

Associate Dean

Francis Tanglao Aguas, MFA

Westphal BRIDGE Scholars,

Program Director

Denise Marie Snow

Executive Assistant to the Dean and Administrator

Mysha Harrell

Catalyst Fellows

Creatives Activating Talent, Advocacy, & Leadership Yielding

Social Transformation

Monyvathana Ear, Eva Krewson

CGI/Bridge Assistants

Emily Sze

Volume 1, Issue 2, 2025

Publisher & Editor-in-Chief

Francis Tanglao Aguas

Head Writer

Ioana A. Racu

Graphic Designer

Monyvathana Ear

Photographer

Eva Krewson